Abstract

While it has been recently recognized that freshwater ecosystems may significantly offset the terrestrial carbon sink through emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4), empirical data on the magnitude of these sources are still scarce, in particular in temperate regions. In this study, we measured the near-surface dissolved concentrations of CH4 and CO2 from 40 lakes in the Alpine area to estimate their potential for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. We hypothesized (1) a temperature-driven gradient of dissolved gas concentrations in terms of elevation and latitude of the lakes and (2) that lower concentrations would be measured in man-made reservoirs compared to natural lakes. Average CH4 and CO2 surface dissolved concentrations amounted to 1.10 ± 1.30 and 36.23 ± 31.15 µmol L−1, respectively. All the lakes, except for one, were supersaturated, exceeding ambient atmospheric CH4 and CO2 concentrations by a factor of 400 ± 424 and 2.43 ± 2.29, respectively. Consistent with our hypothesis, we found lower surface dissolved GHG concentrations in man-made reservoirs compared to natural lakes, which was shown to be related to their greater depth. Even though temperature is known to affect multiple physico-chemical and biological processes governing the strength of the uptake, release and conversion of CH4 and CO2, and temperature is inversely related to elevation, no relationship between dissolved GHG concentrations and elevation could be determined. This is believed to be the result of the overriding importance of lake depth for near-surface CH4 concentrations and the lack of explanatory variables related to lake carbon cycling. Overall, this study suggests that lakes in the Alpine region act as sources of CO2 and CH4 to the atmosphere and that further research should be carried out to quantify the actual GHG emissions from Alpine freshwater bodies and how these are affected by ongoing changes in climate and land use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) are the most studied greenhouse gases (GHG) due to their global warming potential and their recent concentration increase in the atmosphere (Ciais et al. 2013). The largest natural sources for CO2 are the ocean, terrestrial plant respiration and organic matter decomposition and its main anthropogenic source are industrial activities, whereas CH4 emissions come from anthropogenic activities and wetlands are considered as main natural emitters for CH4 (Ciais et al. 2013).

Until recently, inland waters (lakes, rivers, and reservoirs) were not integrated into the carbon budget. A re-evaluation of the surface area of lakes (Downing et al. 2006), reservoirs and small ponds showed that these inland waters cover more than 3% of Earth’s surface, which is twice as high as previous estimates. Cole et al. (2007) showed that, despite their small surface area, freshwaters were receiving as much carbon as the ocean making them not only “pipes” transporting carbon from land to oceans, but also “reactors”, transforming terrestrial (allochthonous) carbon. Tranvik et al. (2009) re-estimated the “active pipes” from Cole et al. (2007) and evaluated that about 48.3% of this carbon is released to the atmosphere as CO2, whereas 20.7% is buried in the sediments, mainly by lakes, reservoirs and wetlands and the remaining 31% is directed towards the oceans by rivers and ground waters. Bastviken et al. (2011) were able to establish a global estimation of CH4 emissions, where 61.2% were emitted as ebullition, 11% as diffusive fluxes, and the remaining 27.8% was stored in the systems.

Previous studies on greenhouse gases emissions from freshwaters were mainly focused on tropical reservoirs, and showed that these were significant CH4 emitters, through diffusion and bubbling emissions (Abril et al. 2005; Borges et al. 2011). Boreal lakes were also found to be significant emitters of CH4 and CO2 (Huttunen et al. 2003). In temperate regions, and particularly the Alpine area, few studies on dissolved concentrations and emissions of GHG have been done so far, and were mainly focused on hydropower reservoirs (Del Sontro et al. 2010; Diem et al. 2012). The general scarcity of data, in particular for natural lakes, makes generalizations of GHG emissions from lakes in the Alpine area highly uncertain. Because of the technical difficulties associated with direct measurements of the lake-atmosphere GHG exchange across a large number of lakes and effort needed, the near-surface water dissolved GHG concentrations, is usually used as a proxy for the lake GHG emission potential (Schilder et al. 2013).

The overarching aim of the present study is to therefore improve the knowledge of the potential of Alpine lakes to act as sources for GHG. As direct measurements of the lake-atmosphere GHG exchange across a larger number of lakes representative of the Alpine area are very time consuming, we decided to quantify the near-surface water dissolved GHG concentrations, which can be considered a proxy for the lake emission potential (Schilder et al. 2013). More specifically, we aimed to (1) quantify near-surface dissolved concentrations of CH4 and CO2 from 40 natural and man-made lakes over an elevation and a latitudinal transect across the Eastern Alps from the Trentino (Italy), South Tyrol (Italy) and North Tyrol (Austria) regions, and to (2) investigate whether a statistical model predicting CH4 and CO2 surface dissolved concentrations can be developed based on readily available lake characteristics.

The Alpine region is characterized by narrow valleys that allow the construction of numerous reservoirs at higher elevations for electricity production, that result in deep and large lakes with smaller and less productive catchments compared to lower elevations, in this way, reducing the allochthonous input (Diem et al. 2012). We thus hypothesized (H1) to observe less dissolved GHGs and as a consequence fewer emissions in higher-elevation reservoirs, compared to lower-elevation natural lakes in the Alpine area.

Water temperature is a key abiotic parameter known to affect multiple physico-chemical and biological processes governing the strength of the uptake, release, and conversion of GHG. We thus hypothesized (H2) that dissolved GHG concentrations would increase with surface water temperature (Yvon-Durocher et al. 2014) and therefore, we expected a decrease of dissolved CH4 concentrations with lake elevation and latitude.

Materials and methods

Study sites

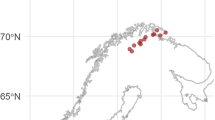

We selected a set of 40 lakes in Trentino (Italy), South Tyrol (Italy), and North Tyrol (Austria) (Table 1, Fig. 1) distributed along gradients of latitude, from 45.52° to 47.38°, longitude from 10.31° to 12.34°, and elevation, from 240 m above sea level (a.s.l.) to 1800 m a.s.l. The selected lakes exhibit a large diversity in terms of depth, from 3.5 to 150 m (on average), surface area (from 0.020 to 6.8 km2), as well as trophic state, type, and size of the catchment. For the lakes for which trophic state was available, it ranged from olitgotrophic (nine lakes), meso-eutrophic (one lake), mesotrophic (17 lakes) to eutrophic (two lakes). Oligotrophic lakes were all situated above 900 m a.s.l., whereas mesotrophic lakes were distributed from 200 to 1500 m a.s.l. The meso-eutrophic lake was situated at 500 m a.s.l. and the eutrophic lakes were between 500 and 1200 m a.s.l. For 21 lakes, the size of the catchment was not available. It was then estimated by calculation using Google Earth and determining the surrounding of the lakes for the limits of the watershed, considering that the summit of the mountains would be limits of the watershed. Among this set of 40 lakes, five are man-made reservoirs: Speicher Stillup, Schlegeis Speicher, Santa Giustina, Valdora and Zoccolo; three lakes are natural in origin, but used for hydroelectricity production: Achensee, Cavedine and Molveno; and the rest are natural lakes.

Ancillary measurements

At each sampling site, water temperature, dissolved oxygen (DO) and pH were measured in situ (about 20 cm depth) with a portable probe (Hach HQ 40d, LDO101, Loveland, CO, USA). pH was later used to recalculate the initial CO2 concentration of the sample.

Field measurements and GHG collection

Measurements and sampling were performed at a minimum distance of 10 m from the shore in order to ensure the absence of disturbances induced by the shore (micro waves) and the release of GHG at the littoral zone that could bias the sampling (Hofmann et al. 2010). As one of our hypotheses relies on the elevation of lakes, attention was paid to sample lakes in the same range of elevation and with similar characteristics, while we visited lakes in the same geographical region. Sampling was done during daytime between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m. Central European time, from 7th August until 30th of September 2014.

To evaluate the dissolved concentrations of CH4 and CO2, surface water samples were taken at about 20 cm water depth. A total of 78 samples were collected for 40 lakes visited (Table S1). Of the total 40 lakes sampled, 14 lakes were sampled once, 17 lakes were sampled twice, 6 lakes were sampled 3 times, and 3 lakes were sampled 4 times. Two lakes were sampled at two different sites: Achensee, due to its large surface, and Santa Giustina for its branched aspect. Among those, eight lakes (Canzolino, Levico, Caldonazzo, Toblino, Caldaro, Schwarzsee, Pillersee, Reintalersee) exhibited high values of dissolved methane concentrations after the first round of sampling and were thus visited a second time (between 26th and 30th of September 2014). Samples were taken manually with a surface water sampler (Guérin et al. 2007) and filled into 60 mL brown glass vials until overflow of about three times the volume of the bottle. To stop any biological activity, samples were acidified with copper chloride (Diem et al. 2012). The vials were then closed, gas tight, with a rubber stopper and an aluminum cap and were kept in the dark, bottom up, to avoid any potential gas leak from the cap, at room temperature until analysis. Analyses were performed within 1 month.

CH4 and CO2 analysis

Prior to the analysis, a headspace was created in the vials by displacing water, about one-third of the total volume of the bottle, with nitrogen (Guérin and Abril 2007). The vial was vigorously shaken until equilibrium, for around 30 s, to shift dissolved CH4 and CO2 from the water phase to the gas phase. Samples were kept bottom up in the dark until analysis. Analyses of dissolved GHG were done using an Agilent 7890A Gas Chromatographer (GC) equipped with a Flame Ionization Detector (FID) for the CH4 compound and a Thermal Conductivity Detector (TCD) for the CO2 compound. Two injections per sample, of 0.5 mL each, were done. If the difference between two injections, for the same gas, was more than 5%, a third injection was done. The GC was also equipped with an Electron Capture Detector for N2O determination, however no significant concentrations of nitrous oxide were detected. A commercial gas standard mixture (CH4 at 8.11 ppm, CO2 at 501 ppm and N2O at 903 ppb) was used for calibration. The limit of detection is below 1 ppm (1.4 10−3 µmol L−1) and 5 ppm (0.22 10−3 µmol L−1) for CH4 and CO2, respectively. As samples were acidified, all dissolved inorganic carbon was shifted to free CO2, and the initial amount of CO2 (before acidification) in the headspace was determined using carbonate equilibrium and pH data (collected before and after acidification). Dissolved concentrations of the two GHGs were calculated using their solubility according to Weiss (1974). As lake pH was used to calculate the dissolved CO2 concentration, pH was not further used as an explanatory variable in order to avoid spurious correlations.

Statistical analysis

A first data visualization indicated that the dataset was not normally distributed and had to be log-transformed base 10 (log(X + 1)) for further statistical analysis. For both gases, the differences between first sampling and second sampling were tested (analysis of covariance of the two groups), but as no significant differences (p > 0.5) were observed, the data from all samplings were pooled for further data analyses. A simple Welch t-test was used in order to see if there were any differences between natural lakes and reservoirs in terms of surface dissolved GHG. To see how variables were correlated to each other, the Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated for all variables of the dataset.

To identify potential drivers of CH4 and carbon dioxide dissolved concentrations, a principal component analysis (PCA) was applied on the dataset using the FactoMineR package. The PCA was followed by a hierarchical clustering analysis on the data, without any a priori grouping (e.g. reservoirs vs natural lakes, by region, etc.).

Finally, a stepwise linear regression, using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to assess the quality of the model, was used to select the minimum adequate model. All statistical analyses were done using the R software (Team R Core 2012).

Results

Surface dissolved concentration

The near-surface waters of all lakes, except for one (Schlegeis Speicher, a reservoir) where no methane could be measured, were supersaturated with both CH4 and CO2, i.e. their dissolved concentrations were higher compared to the atmospheric concentration. On average, surface CH4 dissolved concentrations exceeded ambient concentrations by a factor of 400 ± 427 (range 0–1965), despite the well-oxygenated water at the surface. CH4 dissolved concentrations range and average (± standard deviation) were 0–5.89 µmol L−1-0 concentration indicates that the CH4 concentration was below the limit of detection—and 1.1 ± 1.3 µmol L−1, respectively. CO2 surface dissolved concentrations exceeded the atmospheric background by a factor of 3.27 ± 2.17, ranging from 1.07 to 10.95, with a range of concentration, of 2.14–150.41 µmol L−1, and average of (± standard deviation) 36.23 ± 31.15 µmol L−1, respectively.

Hierarchical clustering

A hierarchical clustering was applied to characterize the dataset, distinguishing four groups (Fig. 2). Cluster 1 was only composed of natural lakes and characterized by the highest values of CH4 and CO2. It also included the shallowest and smallest lakes. Cluster 4, which was the most different compared to the other clusters, was mainly composed by reservoirs, except for two natural ones (Caldonazzo and Plansee). The main feature of this group is that the lakes were the deepest and the largest in term of surface area, with the lowest concentrations of dissolved CH4 and CO2, contrasting with Cluster 1. Cluster 3 was mainly composed of reservoirs and included only one natural lake (Braies). This cluster was characterized by the highest elevations and the lowest surface water temperatures. CH4 and CO2 surface concentrations were the second lowest among all the clusters. Finally, Cluster 2, composed only of natural lakes, had similar average dissolved CO2 concentrations as Cluster 3, 28.56 and 29.57 µmol L−1, respectively, however contrary to the others clusters, none of the independent variables exhibited characteristic features for this group.

Statistical analysis

The correlation table (Pearson correlation) and the PCA (Table 2; Fig. 3) showed that methane was significantly positively correlated with temperature and significantly negatively correlated with surface area, depth and type of lake (Table 2). No significant correlations were found for dissolved CO2 concentrations. The surface dissolved CH4 and CO2 concentrations decreased rapidly with lake depth until around 25 m depth, at which point concentrations became independent of depth (Figs. 4, 5). This is confirmed by the PCA analysis (Fig. 3), where dissolved GHG arrows are opposite to surface area and depth. The same exponential decrease was observed for surface CH4 and CO2 concentrations against lake surface area (Figs. 4, 5), as a consequence of the significant positive correlation existing between lake depth and surface area (Table 2). As all reservoirs, except for one (Speicher Stillup), were deeper than 50 m (significant positive correlation between depth and lake type; Table 2), the highest CH4 surface concentrations were found almost exclusively in natural lakes (Fig. 4). A Welch two-sample t-test was performed on the dataset to understand if there was any difference between reservoirs and natural lakes. Results showed that natural and reservoir are different for both CH4 and CO2 dissolved concentrations (p < 0.001 and p = 0.0208, respectively). The decrease of surface dissolved CO2 concentration with lake depth (Fig. 5) was less pronounced compared to CH4, and only a few shallow lakes had high concentrations (> 80 µmol L−1) of CO2, explaining the absence of significant correlation for CO2 as opposed to CH4 (Table 2). Surface CO2 concentrations of natural lakes deeper than 20 m were comparable to those of reservoirs.

Methane dissolved concentrations as function of a lake depth, b surface area, c elevation, and d temperature. Triangles represent the log dissolved (CH4 + 1) concentrations for natural lakes, black diamonds represent log dissolved (CH4 + 1) concentrations for reservoirs lakes. The solid lines represent linear regressions of all lakes pooled together [r2 adj. (depth) = 0.40; r2 adj. (temperature) = 0.15 r2 adj. (surface area) = 0.15]; the dashed lines represent the 95% confidence intervals

Explanatory variables

In contrast to our hypothesis that surface dissolved GHG concentrations would decrease with elevation, no clear correlation between both surface dissolved CH4 and CO2 concentration and elevation could be found, both with the regression analysis (Figs. 4, 5) and PCA (Fig. 3). Lake elevation and temperature were inversely related in the data set (p < 0.05; Table 2), lake elevation thus appears to represent a poor proxy for lake temperature as a driver for GHG concentrations. Again, in contrast to H2, no latitudinal pattern was observed within the dataset regarding CH4 compound (Table 2).

All reservoirs had measured surface temperatures lower than 20 °C and the lowest values of surface dissolved CH4 concentration (Fig. 4). Contrary to CH4, where highest dissolved surface concentrations corresponded to highest surface temperatures, the highest surface CO2 concentrations corresponded to surface temperatures around 18 °C (Fig. 5).

The minimum adequate model based on the stepwise linear regression analysis suggests that surface dissolved CH4 concentration can be modelled based on lake depth and water surface temperature (RMSE = 1.59 µmol L−1 ; adjusted R2 = 0.47) expressed by the following equation:

Regarding surface dissolved CO2 concentration, the minimum adequate model proposed included dissolved oxygen and elevation (RMSE = 45.88 µmol L−1; adjusted R2 = 0.06) as:

Discussion

Methane concentrations

The range of measured surface concentrations of the dataset (0.00–5.89 µmol L−1) was of the same order of magnitude as boreal or other Alpine lakes (0.03–4.00 µmol L−1) (Bastviken et al. 2008; Juutinen et al. 2009; Schubert et al. 2010; Diem et al. 2012; Tang et al. 2014; Natchimuthu et al. 2014). Except for one (Schlegeis Speicher, reservoir), all the lakes were supersaturated in surface dissolved CH4 with respect to the atmospheric concentration, despite the well-oxygenated water surface layer (Table S1). These results are in accordance with Tang et al. (2014) and Grossart et al. (2011), who also found a CH4 supersaturation at the surface of lake Stechlin (Germany), however, at a lower range of concentrations (0.09–0.76 µmol L−1) compared to the results of this study. They also showed that an oversaturation of CH4 was overlaying a well-oxygenated mid-water layer. Similar to lake Stechlin, a supersaturation of CH4 was observed in the mesotrophic lake Hallwil (Donis et al. 2017), and the stratified lake Constance (Schulz et al. 2001). The CH4 paradox regarding CH4 supersaturation, its origin and its contribution to surface concentrations is still under debate. According to Wang et al. (2017), this CH4 oversaturation layer would be produced by phototrophs, together with oxygen tolerant methanogens, leading to a pelagic methane-enriched zone. Whereas, Fernàndez et al. (2016) stated that CH4 surface concentrations would mainly come from shallow zones, where water is rich in methane. In order to verify if Alpine lakes also exhibit this oversaturated layer of CH4 overlaying a well-oxygenated water layer, CH4 samples along the water column would be needed. In addition, ebullition, methane-rich air bubbles rising from the lake bottom, may be contributing to the observed super-saturation of surface waters (McGinnis et al. 2006; Tang et al. 2014; Deshmukh et al. 2014).

Lake surface temperature is closely related to air temperature (Livingstone and Lotter 1998; Livingstone and Dokulil 2001). As CH4 production is temperature dependent (Zeikus and Winfrey 1976; Dunfield et al. 1993; Duc et al. 2010), we hypothesized (H2) a positive relationship between surface dissolved CH4 concentrations and lake temperature (r = 0.39, p < 0.001). Commonly, elevation is seen as a proxy for temperature due to the decrease of air temperature with elevation. Accordingly, we further expected a decrease of dissolved CH4 concentration with increasing elevation. Indeed, we observed a negative correlation between lake temperature and elevation and a significant positive relationship between lake temperature and dissolved methane concentrations, however, no significant relationship between lake elevation and dissolved methane concentrations was found (Table 2). This suggests that lake elevation is a poor proxy for capturing the relationship between lake temperature and dissolved CH4 concentrations, possibly because other factors, e.g. lake depth and/or surface area, are confounding the relationship with elevation. Similarly, no relationship was observed between CH4 concentration and latitude, which suggests that the latitudinal gradient between the sampled lakes was either too small to result in a measurable trend in terms of surface dissolved CH4 and/or confounded by other factors.

Abril et al. (2007) showed that turbidity was negatively correlated to CH4 concentrations in river environments, whereas Oswald et al. (2015) showed that light was promoting the CH4 oxidation by CH4 oxidizing bacteria which was also confirmed by Dumestre et al. (1999), for both natural and artificial lakes. While turbidity was not measured in the present study, some of the highest methane concentrations were measured in lakes that were characterised by dark brownish colours (e.g. Möserer See, Levico, Caldaro), corresponding with the above-mentioned studies.

The minimum adequate model indicated that CH4 could be predicted through a positive relationship with water surface temperature and a negative relationship with depth, which is consistent with previous studies demonstrating the relationship between CH4 and temperature (Schütz et al. 1989; Rasilo et al. 2014).

The near-surface dissolved CH4 concentration decreased with depth of the lakes (Fig. 4). In deep lakes, the oxidation of CH4 into CO2 prevails during the diffusion of CH4 molecules upwards through the water column (Bastviken et al. 2004). The deeper a lake is, the less dissolved CH4 is measured at the surface. This is consistent with results of this dataset, where the lowest dissolved CH4 concentrations were measured for the deepest lakes. Similar results were also found for boreal lakes, where CH4 was negatively correlated with lake depth and surface CH4 concentrations measured were the highest in shallow lakes (Juutinen et al. 2009). Juutinen et al. (2009) and Borges et al. (2011) also found a negative correlation with lake surface area, as observed for this dataset (Table 2). The low concentrations measured at the surface can also be explained by the stratification created in the water column of deep lakes, which supports the accumulation and isolation of GHG at the bottom of the lakes (Salmaso and Mosello 2010). In addition, surface sediments may warm faster in shallow lakes, resulting in a larger methane production, which contributes to higher concentrations in shallow lakes (Thebrath et al. 1993).

Reservoirs CH4 concentrations were comparable with the results that Diem et al. (2012) found for Swiss hydropower reservoirs within a similar range of elevation. Similarly to this study, Diem et al. (2012) measured surface CH4 concentrations just at or above supersaturation. The results of the present study for the reservoirs are also within the same order of magnitude found by Duchemin et al. (1995) for two hydroelectric reservoirs situated in the Canadian boreal region. This, compared to natural lakes, is typically much shorter residence time of surface waters, which affects carbon input, processing, and output (Adrian et al. 2009; Venkiteswaran et al. 2013), may further contribute to the observed lower dissolved CH4 concentrations in reservoirs, and explain the difference in term of dissolved CH4 (and CO2) between natural lakes and reservoirs.

The significant correlation between lake depth and surface area (Table 2) found for Alpine water bodies is also supported by Kankaala et al. (2013) and Juutinen et al. (2009) for boreal water bodies, showing that lake depth and surface area were positively correlated. They also reported a negative correlation between CH4 surface concentration and lake surface area. As observed for boreal regions (e.g. Bastviken et al. 2004), lakes situated in the Alpine area were also characterized by a negative correlation between CH4 surface concentration and lake surface area.

Carbon dioxide concentration

The range of dissolved CO2 concentration for both natural lakes and reservoirs was in the same order of magnitude as the one found for Swiss reservoirs, which were in the same range of elevations (Diem et al. 2012), and for other lakes (Casper et al. 2000; Sobek et al. 2003; Lazzarino et al. 2009; Panneer Selvam et al. 2014).

As observed for CH4, all lakes were supersaturated in surface dissolved CO2 (average 36 µmol L−1) compared to the CO2 atmospheric concentration (13.74 µmol L−1). These results are consistent and agree with the findings of Cole et al. (1994), who analyzed a worldwide set of lakes in which 87% of them were supersaturated, on average by a factor of three compared to the atmospheric concentration. This is also consistent with Sobek et al. (2005), who showed that most of the world’s lakes were supersaturated in CO2, without following a latitudinal pattern, and that temperature was not a good predictor for CO2 partial pressure.

The minimum adequate linear model for CO2 included a negative relationship with elevation and dissolved oxygen. The low value of the adjusted r2 and the relatively high value of the RMSE and the fact that no single variable was significantly correlated with CO2 (Table 2), suggest that other explanatory variables are required to establish a robust linear model for CO2, like dissolved organic carbon, chlorophyll a, or ion contents. As shown by Xenopoulos et al. (2003), the concentration of dissolved organic carbon decreases with elevation, the inclusion of elevation in the minimum adequate model may thus, partially and indirectly, account for differences in dissolved organic carbon contents between lakes. According to Kosten et al. (2010), CO2 partial pressure (pCO2) could be partially explained by water temperature, together with other variables such as chlorophyll a, humic substances inflow or evaporation. CO2 concentration is then driven by a group of variables, which could explain why temperature, by itself, did not explain CO2 variability for this dataset.

As for dissolved CH4, similar trends, albeit not significant, were observed for dissolved CO2 as a function of lake depth and elevation: higher concentrations of dissolved CO2 were found for shallow natural lakes, compared to reservoirs which all, except two of them, were deeper than 100 m. The range of CO2 concentrations for the reservoirs in this dataset was lower than the range found by Diem et al. (2012), and lower than boreal reservoirs (Duchemin et al. 1995) and tropical reservoirs (Abril et al. 2006). Compared to the reservoirs studied by Duchemin et al. (1995) and Abril et al. (2006), reservoirs for this study were mainly at high elevation, explaining the low values of CO2 measured. However, for the same range of elevation in the study of Diem et al. (2012) and this one, the results found for Swiss hydropower reservoirs were up to five times higher than our dataset. No clear explanation could be found to explain the difference between the two sets of reservoirs, however, this could be due to the age of the reservoirs (Abril et al. 2005). Another factor explaining the near-surface concentration differences between lakes is the presence of stratification, which typically goes along with an accumulation of CO2 (and CH4) in bottom waters. As shown by Kortelainen et al. (2006), there is a positive relationship between CO2 concentrations in surface waters and in water layers above the sediment that can lead to supersaturation. Future studies should aim at supplementing near-surface water concentrations with samples from bottom waters and/or determine oxygen profiles.

Kankaala et al. (2013), found a negative correlation between the surface CO2 concentration and surface area of boreal lakes. Such a correlation was not found for our dataset (Table 2), presumably because, as shown by the linear model, surface dissolved CO2 in the alpine area is explained by a combination of variables.

Cluster anaysis

When testing correlations between CO2 and CH4 concentrations for each cluster, it appeared that none was present for Cluster 4 (data not shown here). This cluster was composed by the largest and the deepest lakes—mostly reservoirs—with supposed small allochthonous input. CO2 can be produced at the surface of the water by respiration, but can also originate from the oxidation of CH4, produced in the anoxic layer by methanogenesis, while reaching the epilimnion of the lake. These differences could explain the absence of a correlation in Cluster 4. Distinguishing natural lakes from reservoirs, as implied in H1, was not a relevant criterion, since reservoirs were found in two of the four clusters (Fig. 2).

On the other hand, Cluster 1, was characterized by the highest values for dissolved CH4 and CO2 and the highest surface water temperature, corroborating the relationship between CH4 and water temperature (Yvon-Durocher et al. 2014) and our hypothesis (H1). Lakes in this cluster were also the smallest and the shallowest, and dissolved CH4 and CO2 were correlated to each other (r2 = 0.60) suggesting that both compounds would have the same origin, and that part of CO2 would come from the oxidation of CH4, and where temperature would enhance GHG production.

The results of the cluster analysis can be used to guide site selection of future studies. In particular for experimental approaches that are more time consuming compared to the sampling in this study and thus not practical at multiple lakes (e.g. direct lake-atmosphere flux measurements using the eddy covariance method; Eugster et al. 2011), the cluster analysis may help to select the most appropriate study site with respect to the study objectives and experimental limitations (e.g. flux detection limit).

Conclusions

The main result of this study is that the near-surface waters of all investigated lakes, except one, were super-saturated in both surface dissolved CH4 and CO2 suggesting that these lakes tend to act as sources of CH4 and CO2 to the atmosphere. The water-atmosphere exchange of trace gases depends, in addition to the gradient between dissolved near-surface water and ambient air concentrations, on the transfer velocity across the water–air interface (Wanninkhof 2014). Previous studies that quantified both dissolved concentrations and fluxes of CH4 and CO2 reported super-saturation ratios similar to this study that went along with significant CH4 and CO2 emissions (Sobek et al. 2003; Bastviken et al. 2008; Diem et al. 2012; Panneer Selvam et al. 2014; Natchimuthu et al. 2014). Even though this study did not directly quantify the lake-atmosphere exchange or the transfer velocity across the water–air interface, our dissolved near-surface water concentrations thus suggest that lakes in the Alpine region would act as carbon sources to the atmosphere.

The variability of near-surface water dissolved CH4 concentrations was best explained by water temperature, higher temperatures increasing the production of CH4, and lake depth, methane oxidation reducing near-surface concentrations in deeper lakes. Given that the Alps have warmed twice as fast compared to the global average during the past 100 years (Auer et al. 2007), the significant relationship between near-surface water dissolved CH4 concentrations and water temperature warrants further studies on the magnitude of the resulting atmospheric feedback. Near-surface water dissolved CO2 concentrations were best predicted by dissolved oxygen and elevation, however the overall fraction of explained variance was very low, suggesting that critical explanatory factors were missing for CO2.

Further studies are encouraged that seek to clarify the causes and drivers underlying the observed scatter in the data, in particular for CO2, and additionally attempt to confirm the implied relationship between dissolved gas concentrations and the corresponding water-atmosphere exchange.

References

Abril G, Guérin F, Richard S et al (2005) Carbon dioxide and methane emissions and the carbon budget of a 10-year old tropical reservoir (Petit Saut, French Guiana). Global Biogeochem. Cycles 19:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GB002457

Abril G, Richard S, Guérin F (2006) In situ measurements of dissolved gases (CO2 and CH4) in a wide range of concentrations in a tropical reservoir using an equilibrator. Sci. Total Environ. 354:246–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2004.12.051

Abril G, Commarieu M-V, Guérin F (2007) Enhanced methane oxidation in an estuarine maximum turbidity. Limnol Oceanogr 52:470–475

Adrian R, O’Reilly C, Zagarese H et al (2009) Lakes as sentinels of climate change. Limnol Oceanogr 54:2283–2297

Auer I, Böhm R, Jurkovic A et al (2007) HISTALP: historical instrumental climatological surface time series of the Greater Alpine Region. Encycl Atmos Sci 27:17–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.1377

Bastviken D, Cole J, Pace M, Tranvik L (2004) Methane emissions from lakes: dependence of lake characteristics, two regional assessments, and a global estimate. Glob Biogeochem Cycles 18:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1029/2004GB002238

Bastviken D, Cole JJ, Pace ML, Van de-Bogert MC (2008) Fates of methane from different lake habitats: connecting whole-lake budgets and CH4 emissions. J Geophys Res Biogeosci. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JG000608

Bastviken D, Tranvik L, Downing JA, Crill PM, Enrich-prast A (2011) Freshwater methane emissions offset the continental carbon sink. Science 331(6013):50. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1196808

Borges A, Abril G, Delille B, Descy J-P, Darchambeau F (2011) Diffusive methane emissions to the atmosphere from Lake Kivu (Eastern Africa). J Geophys Res 116:G03032. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JG001673

Casper P, Maberly S, Hall G, Finlay B (2000) Fluxes of methane and carbon dioxide from a small productive lake to the atmosphere. Biogeochemistry 49:1–19

Ciais P, Sabine C, Bala G, Bopp L, Brovkin V, Canadell J (2013) Carbon and other biogeochemical cycles. In: Stocker TF, Qin D, Plattner G-K, Tignor M, Allen SK, Boschung J, Nauels A, Xia Y, Bex V, Midgley PM (eds) Climate change 2013: the physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY, USA, pp 465–570

Cole JJ, Caraco NF, Kling GW, Kratz TK (1994) Carbon dioxide supersaturation in the surface waters of lakes. Science 265(5178):1568–1570

Cole JJ, Prairie YT, Caraco NF et al (2007) Plumbing the global carbon cycle: integrating inland waters into the terrestrial carbon budget. Ecosystems 10:172–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-006-9013-8

Del Sontro T, Mcginnis DF, Sobek S, Ostrovsky I, Wehrli B (2010) Extreme methane emissions from a swiss hydropower reservoir: contribution from bubbling sediments. Environ Sci Technol 44:2419–2425. https://doi.org/10.1021/es9031369

Deshmukh C, Serça D, Delon C et al (2014) Physical controls on CH4 emissions from a newly flooded subtropical freshwater hydroelectric reservoir: Nam Theun 2. Biogeosciences 11:4251–4269. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-11-4251-2014

Diem T, Koch S, Schwarzenbach S, Wehrli B, Schubert CJ (2012) Greenhouse gas emissions (CO2, CH4, and N2O) from several perialpine and alpine hydropower reservoirs by diffusion and loss in turbines. Aquat Sci 74:619–635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00027-012-0256-5

Donis D, Flury S, Stöckli A, Spangenberg JE, Vachon D, McGinnis DF (2017) Full-scale evaluation of methane production under oxic conditions in a mesotrophic lake. Nat Commun 8:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01648-4

Downing JA, Prairie YT, Cole JJ et al (2006) The global abundance and size distribution of lakes, ponds, and impoundments. Limnol Oceanogr 51:2388–2397. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2006.51.5.2388

Duc NT, Crill P, Bastviken D (2010) Implications of temperature and sediment characteristics on methane formation and oxidation in lake sediments. Biogeochemistry 100:185–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-010-9415-8

Duchemin E, Lucotte M, Canuel R, Chamberland A (1995) Production of the greenhouse gases CH4 and CO2 by hydroelectric reservoirs of the boreal region. Glob Biogeochem Cycles 9:529–540

Dumestre JF, Guézennec J, Galy-Lacaux C, Delmas R, Richard S, Labroue L (1999) Influence of light intensity on methanotrphic bacterial activity in Petit Saut reservoir, French Guiana. Appl Environ Microbiol 65:534–539

Dunfield P, Knowles R, Dumont R, Moore TR (1993) Methane production and consumption in temperate and subarctic peat soils: response to temperature and pH. Soil Biol Biochem 25:321–326

Eugster W, DelSontro T, Sobek S (2011) Eddy covariance flux measurements confirm extreme CH4 emissions from a Swiss hydropower reservoir and resolve their short-term variability. Biogeosciences 8:2815–2831. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-8-2815-2011

Fernández JE, Peeters F, Hofmann H (2016) On the methane paradox: transport from shallow-water zones rather than in situ methanogenesis is the mayor source of CH4 in the open surface water of lakes. J Geophys Res Biogeosci 121:2717–2726. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JG003586

Grossart H-P, Frindte K, Dziallas C, Eckert W, Tang KW (2011) Microbial methane production in oxygenated water column of an oligotrophic lake. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:19657–19661. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1110716108

Guérin F, Abril G (2007) Significance of pelagic aerobic methane oxidation in the methane and carbon budget of a tropical reservoir. J Geophys Res Biogeosci 112:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JG000393

Guérin F, Abril G, Serça D, Delon C, Richard S, Delmas R, Tremblay A, Varfalvy L (2007) Gas transfer velocities of CO2 and CH4 in a tropical reservoir and its river downstream. J Mar Syst 66:161–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmarsys.2006.03.019

Hofmann H, Federwisch L, Peeters F (2010) Wave-induced release of methane: littoral zones as source of methane in lakes. Limnol Oceanogr 55:1990–2000. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2010.55.5.1990

Huttunen JT, Alm J, Liikanen A, Juutinen S, Larmola T, Hammar T, Silvola J, Martikainen PJ (2003) Fluxes of methane, carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide in boreal lakes and potential anthropogenic effects on the aquatic greenhouse gas emissions. Chemosphere 52:609–621. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0045-6535(03)00243-1

Juutinen S, Rantakari M, Kortelainen P, Huttunen JT, Larmola T, Alm J, Silvola J, Martikainen PJ (2009) Methane dynamics in different boreal lake types. Biogeosciences 6:209–223. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-6-209-2009

Kortelainen P, Rantakari M, Huttunen JT et al (2006) Sediment respiration and lake trophic state are important predictors of large CO2 evasion from small boreal lakes. Glob Chang Biol 12:1554–1567. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01167

Kankaala P, Huotari J, Tulonen T, Ojala A (2013) Lake-size dependent physical forcing of carbon dioxide and methane effluxes from lakes in a boreal landscape. Limnol Oceanogr 58:1915–1930. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2013.58.6.1915

Kosten S, Roland F, Da Motta Marques DML, Van Nes EH, Mazzeo N, Sternberg LDSL, Scheffer M, Cole JJ (2010) Climate-dependent CO2 emissions from lakes. Glob Biogeochem Cycles. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009GB003618

Lazzarino JK, Bachmann RW, Hoyer MV, Canfield DE (2009) Carbon dioxide supersaturation in Florida lakes. Hydrobiologia 627:169–180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-009-9723-y

Livingstone DM, Dokulil MT (2001) Eighty years of spatially coherent Austrian lake surface temperatures and their relationship to regional air temperature and the North Atlantic Oscillation. Limnol Oceanogr 46:1220–1227

Livingstone DM, Lotter AF (1998) The relationship between air and water temperatures in lakes of the Swiss Plateau: a case study with palaeolimnological implication. J Paleolimnol 19:181–198

McGinnis DF, Greinert J, Artemov Y, Beaubien SE, Wüest A (2006) Fate of rising methane bubbles in stratified waters: how much methane reaches the atmosphere? J Geophys Res 111:C09007. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JC003183

Natchimuthu S, Panneer Selvam B, Bastviken D (2014) Influence of weather variables on methane and carbon dioxide flux from a shallow pond. Biogeochemistry 119:403–413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-014-9976-z

Oswald K, Milucka J, Brand A, Littmann S, Wehrli B, Kuypers MMM, Schubert CJ (2015) Light-dependent aerobic methane oxidation reduces methane emissions from seasonally stratified lakes. PLoS One 10:1–22. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132574

Panneer Selvam B, Natchimuthu S, Arunachalam L, Bastviken D (2014) Methane and carbon dioxide emissions from inland waters in India—implications for large scale greenhouse gas balances. Glob Chang Biol 20:3397–3407. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12575

R Development Core Team (2012) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, ISBN 3-900051-07-0. https://www.r-project.org/

Rasilo T, Prairie YT, Del Giorgio PA (2014) Large-scale patterns in summer diffusive CH4 fluxes across boreal lakes, and contribution to diffusive C emissions. Glob Chang Biol. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12741

Salmaso N, Mosello R (2010) Limnological research in the deep southern subalpine lakes: synthesis, directions and perspectives. Adv Oceanogr Limnol 1:29–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/19475721003735773

Schilder J, Bastviken D, Van Hardenbroeck M, Kankaala P, Rinta P, Stotter T, Heiri O (2013) Spatial heterogeneity and lake morphology affect diffusive greenhouse gas emission estimates of lakes. Geophys Res Lett 40:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013GL057669

Schubert CJ, Lucas FS, Durisch-Kaiser E, Stierli R, Diem T, Scheidegger O, Vazquez F, Müller B (2010) Oxidation and emission of methane in a monomictic lake (Rotsee, Switzerland). Aquat Sci 72:455–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00027-010-0148-5

Schulz M, Faber E, Hollerbach A, Schröder HG, Güde H (2001) The methane cycle in the epilimnion of Lake Constance. Fundam Appl Limnol 151:157–176. https://doi.org/10.1127/archiv-hydrobiol/151/2001/157

Schütz H, Seiler W, Conrad R (1989) Processes involved in formation and emission of methane in rice paddies. Biogeochemistry 7:33–53

Sobek S, Tranvik LJ, Cole JJ (2005) Temperature independence of carbon dioxide supersaturation in global lakes. Global Biogeochem Cycles. https://doi.org/10.1029/2004GB002264

Sobek S, Algesten G, Bergstrom A-K, Jansson M, Tranvik L (2003) The catchment and climate regulation of pCO2 in boreal lakes. Glob Chang Biol 9:630–641

Tang K, McGinnis D, Frindte K, Bruchert V, Grossart H-P (2014) Paradox reconsidered: methane oversaturation in well-oxygenated lake waters. Limnol Oceanogr 59:275–284. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2014.59.1.0275

Thebrath B, Rothfuss F, Whiticar MJ, Conrad R (1993) Methane production in littoral sediment of Lake Constance. FEMS Microbiol Lett 102:279–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-1097(93)90210-S

Tranvik L, Downing J, Cotner J, Loiselle SA, Striegl RG, Ballatore TJ, Dillon P, Finlay K, Fortino K, Knoll LB, Kortelainen PL, Kutser T, Larsen S, Laurion I, Leech DM, Leigh McCallister S, McKnight DM, Melack JM, Overholt E, Porter JA, Prairie Y, Renwick WH, Roland F, Sherman BS, Schindler DW, Sobek S, Tremblay A, Vanni MJ, Verschoor AM, von Wachenfeldt E, Weyhenmeyer GA (2009) Lakes and reservoirs as regulators of carbon cycling and climate. Limnol Oceanogr 54:2298–2314

Venkiteswaran JJ, Schiff SL, St. Louis VL, Matthews CJD, Boudreau NM, Joyce EM, Beaty KG, Bodaly RA (2013) Processes affecting greenhouse gas production in experimental boreal reservoirs. Glob Biogeochem Cycles 27:567–577. https://doi.org/10.1002/gbc.20046

Wang Q, Dore JE, McDermott TR (2017) Methylphosphonate metabolism by Pseudomonas sp. populations contributes to the methane oversaturation paradox in an oxic freshwater lake. Environ Microbiol 19:2366–2378. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.13747

Wanninkhof R (2014) Relationship between wind speed and gas exchange over the ocean revisited. Limnol Oceanogr Methods 12:351–362. https://doi.org/10.1029/92JC00188

Weiss RF (1974) Carbon dioxide in water and seawater: the solubility of a non-ideal gas. Mar Chem 2:203–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4203(74)90015-2

Xenopoulos MA, Lodge DM, Frentress J, Kreps TA, Bridgham SD, Grossman E, Jackson CJ (2003) Regional comparisons of watershed determinants of dissolved organic carbon in temperate lakes from the Upper Great Lakes region and selected regions globally. Limnol Oceanogr 48:2321–2334. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2003.48.6.2321

Yvon-Durocher G, Allen A, Bastviken D, Conrad R, Gudasz C, St-Pierre A, Thanh-Duc N, Del Giorgio PA (2014) Methane fluxes show consistent temperature dependence across microbial to ecosystem scales. Nature 507:488–491. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13164

Zeikus J, Winfrey M (1976) Temperature limitation of methanogenesis in aquatic sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 31:99–107

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Innsbruck and Medical University of Innsbruck. The study was realized within a Ph.D. project supported by FIRS>T (FEM International Research School) and the University of Innsbruck. The authors would like to thank Christian Ceccon and Giustino Tonon, from the University of Bolzano, for allowing us to use their GC. We also thank Katharina Scholz and Arnaud Godon for their help in the field, and Pietro Franceschi and Florian Kitz for their advise on the statistical part.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Pighini, S., Ventura, M., Miglietta, F. et al. Dissolved greenhouse gas concentrations in 40 lakes in the Alpine area. Aquat Sci 80, 32 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00027-018-0583-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00027-018-0583-2