Abstract

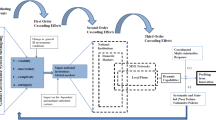

We examine how the organizational structure for diversification decisions involving firms from different countries is affected by the institutional context of the target country. Our theoretical analysis suggests that, as legal systems improve and information asymmetry is reduced, a transition from relational, “firm-like” arrangements to arm's length, “market-like” arrangements takes place. If institutions continue to improve, eventually a threshold is crossed after which arm's length deals edge out internal firm contracting. We provide an empirical test of the model using the sample of international strategic alliances, joint ventures and cross-border mergers involving US firms. Our empirical findings support the predictions of the theory. In addition, we document that US companies entering organizational structures predicted by our model are associated with greater abnormal returns around deal announcements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Differences among countries exist in terms of shareholder and creditor rights (concluding that common-law countries provide greater investor protection than civil-law countries; see La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, & Vishny, 1998), the extent of required accounting disclosure (Ali & Hwang, 2000; Rajan & Zingales, 1998a), approaches toward capital market regulation (Glaeser, Johnson, & Shleifer, 2001), and the overall quality of law and tradition of order (measured by various agencies, e.g., International Country Risk Guide). Countries providing stronger investor protection, better law enforcement, and stricter disclosure requirements and regulation are associated with bigger, more liquid, and more informative capital markets (La Porta et al., 1997). On the other hand, countries with a lack of protection and poor financial and disclosure laws suffer frequent investor expropriation (Johnson, La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, & Shleifer, 2000) and moribund financial markets, generating substantial information asymmetries (Glaeser et al., 2001).

The World Development Report, 2002, Building institutions for markets, devotes an entire section to the financial intermediation sector as a set of institutions that support markets. See Section 4, pp 75–96 of this report.

Recent finance studies (e.g., Desai et al., 2004) have linked international organizational structure choices to the level of optimal ownership. Since optimal ownership structure is often selected to mitigate information asymmetry (e.g., Jensen & Meckling, 1976, 1995), we consider our study complementary to that stream of finance research.

Simon (1951), among others, argued that relational contracts are at the center of the employment relations, and Williamson (1975) argued that relational contracts are the key differentiator of firms and markets.

See Holmstrom and Roberts (1998) for an excellent survey.

This follows the usage in the management literature on the core competence of a firm, such as in Prahalad and Hamel (1990).

We have decided to adopt the terminology “strength of integration” as opposed to “degree of integration”, because degree of integration is often used to connote how vertically integrated a firm is with regard to inputs and outputs. This is quite a different focus from the one we have here.

We refer to the US-based core and the foreign subsidiaries that are associated with it as a conglomerate.

Strictly speaking, the cost parameter γ is also an argument in b j **. However, since this is not a choice variable for the firm, we suppress it to reduce notational clutter.

The advantage of SDC databases is that they contain announcement and completion dates, identities of business partners, and information on the industry of combined assets for virtually all completed business deals over the period of our study. However, some deal-specific information (such as deal size), as well as data describing operations of the business partners – especially of those from outside of the US – is often missing. Consequently, since we want to utilize information for the widest possible sample, most of our tests include only variables characterizing the deal's industry and the characteristics of countries of firms involved in SDC-covered deals. However, our results are very similar when we restrict our sample to include only business combinations where firm-specific Compustat data characterizing US firms can be added to our test specifications.

In addition to the quality of legal system and quality of accounting system variables, we performed the empirical analysis utilizing an inverse measure of cost of debt recovery for various countries (Djankov, La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, & Shleifer, 2002) as a measure of institutional quality. This variable is not the most appropriate for our model, because the Djankov et al. measures are more indicative of barriers to entry rather than information asymmetry or the costs of contractual governance, but the results utilizing this measure are similar to those presented in Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5, and are available from the authors upon request.

It should be mentioned that the statistical significance for medians in Table 2 (as well as in Table 4) is based on the Wilcoxon test. Even though the median values may appear to be quite similar, it is possible for the Wilcoxon test to be significant if rank-ordered distributions of the two subsamples are different.

In addition, our findings are also consistent with Blomström and Zejan (1991), who show that vertically diversifying US firms are more likely to enter organizational structures with shared ownership in order to acquire the expertise of their foreign partners and minimize the costs of information asymmetry associated with managing assets that do not belong to the core business of the US firm.

Industry growth opportunities are measured as median M/B ratio of assets [(MV of equity+Total assets−BV of equity)/Total assets] for all US companies with the same two-digit industry SIC code as the code of the joint venture (or strategic alliance), measured during the year of deal completion. Industry research intensity is measured as median R&D expenses normalized by total assets for all US companies with the same two-digit industry SIC code as the code of either the US bidder (in the case of mergers) or the joint venture or strategic alliance, measured during the year of deal completion.

The variables are defined as follows. If quality of legal (accounting) systems <50th percentile value, then: Quality of legal (accounting) systems: low=Quality of legal (accounting) systemsQuality of legal (accounting) systems: middle=0Quality of legal (accounting) systems: high=0If quality of legal (accounting) systems⩾50th percentile value and quality of legal (accounting) systems <80th percentile value, then Quality of legal (accounting) systems: low=50th percentile valueQuality of legal (accounting) systems: middle=quality of legal (accounting) systems−50th percentile valueQuality of legal (accounting) systems: high=0If quality of legal (accounting) systems⩾80th percentile value, then Quality of legal (accounting) systems: low=50th percentile valueQuality of legal (accounting) systems: middle=80th percentile value−50th percentile valueQuality of legal (accounting) systems: high=Quality of legal (accounting) systems−80th percentile value.

We selected these percentiles to have roughly the same number of deals in all three groups. If we used lower than the 50th percentile to identify the group with the lowest legal and accounting standards, this group would be relatively under-represented. However, our findings are not critically dependent on choices of 50th and 80th percentiles as model thresholds, and even alternative choices (such as terciles) lead to qualitatively similar results.

The positive relationship between the likelihood of an arm's length arrangement and the quality of legal or accounting systems for countries in the below-median region is not a prediction of our model. There can be numerous other forces driving contractual governance choices that are beyond the ambit of our model. In fact, finance research generally predicts a positive relationship between institutional quality and arm's length arrangement (e.g., La Porta et al., 2000). The novelty of our analysis is actually the non-linearity that occurs for countries with average-to-high quality of legal or accounting systems.

We measure the potentially non-linear impact of legal (accounting) standards on organizational structure choices by several dummy variables. DLAWMI (DACTMI) is a dummy variable equal to 1 for observations with value of the quality of legal system (quality of accounting system) greater than or equal to the sample's 50th percentile and lower than the sample's 80th percentile. DLAWHI (DACTHI) is a dummy variable equal to 1 for observations with value of the quality of legal system (quality of accounting system) greater than or equal to the sample's 80th percentile.

In addition, we analyzed the non-linear impact of quality of legal system and quality of accounting system variables by the inclusion of quadratic and cubic terms of these variables (for the full sample and several subsamples based on the high/low values of the quality variables). In most of our specifications, quadratic and cubic terms of quality variables were statistically significant and consistent with the hypothesis that arm's length transactions (joint ventures and strategic alliances) are associated with values of quality of legal system and quality of accounting system at the lower and upper end of the spectrum, whereas firm-like arrangements (mergers) are more likely for values of quality of legal system and quality of accounting system in the middle of the spectrum.

The drop in the numbers of observations utilized in Models 1–5 and 6–7 is caused by the fact that many sample events tracked by the SDC database involve private US entities with data unavailable on Compustat.

Our results do not appear to be time-, industry-, or country-specific. In regressions in Table 3, year and industry fixed effects are included (though not reported in Table 3). p-values are based on standard errors corrected for heteroskedasticity and country-level clustering. At the same time, the significance of the results generated without fixed effects and without error clustering is similar to that reported in Table 3.

Unlike our sample, which consists of newly formed mergers, joint ventures and strategic alliances, Desai et al. (2004) use panel data describing wholly vs partially owned affiliates of US companies.

The deal involves cross-technology transfer if one of the participants transfers technology to another participant or to the alliance (this information is collected from the SDC database).

Similarly to the analysis performed in Table 3, year and industry fixed effects are included (though not reported in Table 5). p-values are based on standard errors corrected for heteroskedasticity and country-level clustering. At the same time, the significance of the results generated without fixed effects and without error clustering is similar to that reported in Table 5.

Parameters α i and β i are estimated from linear regression utilizing returns from days –220 to –20 before the deal announcement date.

The results based on models utilizing the quality of law are similar, though they have lower statistical significance.

Other coefficients have generally anticipated signs (though only those for size are significantly different from zero). The significantly negative coefficient for size is expected, since the total synergies are typically spread over a greater equity base in the case of large deal participants. There is also some evidence suggesting that, at least in the case of mergers, larger bidders are associated with greater returns to targets (e.g., Billett & Ryngaert, 1997; Jarrell & Poulsen, 1989), possibly as a result of overpaying. A positive coefficient for the return on assets suggests that better-performing firms are associated with better business decisions. A positive coefficient for related participants is consistent with the literature suggesting that vertical diversification destroys comparatively greater value (Berger & Ofek, 1995; Rajan et al., 2000; Shin & Stulz, 1998). A positive coefficient for industry growth opportunities is consistent, for example, with the hypothesis that high-growth assets benefit from acquisition, thanks to additional access to financing (Smith & Kim, 1994). All models are controlled for industry and year effects (unreported in the table). p-values are based on standard errors corrected for heteroskedasticity and country-level clustering. At the same time, the significance of the results generated without fixed effects and without error clustering is similar to that reported in Table 6.

References

Alchian, A., & Demsetz, H. 1972. Production, information costs and economic organization. American Economic Review, 62 (5): 777–795.

Ali, A., & Hwang, L. 2000. Country-specific factors related to financial reporting and the value relevance of accounting data. Journal of Accounting Research, 38 (1): 1–21.

Andrade, G., Mitchell, M., & Stafford, E. 2001. New evidence and perspectives on mergers. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15 (2): 103–120.

Antràs, P. 2003. Firms, contracts, and trade structure. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118 (4): 1375–1418.

Antràs, P., & Helpman, E. 2004. Global sourcing. Journal of Political Economy, 112 (3): 552–580.

Asiedu, E., & Esfahani, H. S. 2001. Ownership structure in foreign direct investment projects. Review of Economics and Statistics, 83 (4): 647–662.

Baker, G., Gibbons, R., & Murphy, K. J. 1994. Subjective performance measures in optimal incentive contracts. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109 (4): 1125–1156.

Baker, G., Gibbons, R., & Murphy, K. J. 2002. Relational contracts and the theory of the firm. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117 (1): 39–84.

Beamish, P. W., & Banks, J. C. 1987. Equity joint ventures and the theory of the multinational enterprise. Journal of International Business Studies, 18 (3): 1–16.

Berger, P. G., & Ofek, E. 1995. Diversification's effect on firm value. Journal of Financial Economics, 37 (1): 39–65.

Bergman, N., & Nicolaievsky, D. 2007. Investor protection and the Coasian view. Journal of Financial Economics, 84 (3): 738–771.

Billett, M. T., & Ryngaert, M. 1997. Capital structure, asset structure and equity takeover premiums in cash tender offers. Journal of Corporate Finance, 3 (2): 141–165.

Black, E., Carnes, T., Jandik, T., & Henderson, C. 2007. The relevance of target accounting quality to the long-term success of cross-border mergers. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 34 (1–2): 139–168.

Blomström, M., & Zejan, M. 1991. Why do multinational firms seek out joint ventures? Journal of International Development, 3 (1): 53–63.

Bradley, M., Desai, A., & Han Kim, E. 1988. Synergistic gains from corporate acquisitions and their division between the stockholders of target and acquiring firms. Journal of Financial Economics, 21 (1): 3–40.

Chan, S. H., Kensinger, J. W., Keown, A. J., & Martin, J. D. 1997. Do strategic alliances create value? Journal of Financial Economics, 46 (2): 199–221.

Coase, R. 1937. The nature of the firm. Economica, 4 (16): 386–405.

Demsetz, H. 1993. The theory of the firm revisited. In O. E. Williamson & S. G. Winter (Eds), The nature of the firm: Origins, evolution and development: 159–178. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Denis, D. J., Denis, D. K., & Yost, K. 2002. Global diversification, industrial diversification, and firm value. Journal of Finance, 57 (5): 1951–1979.

Desai, M. A., Foley, C. F., & Hines, J. R. 2004. The costs of shared ownership: Evidence from international joint ventures. Journal of Financial Economics, 73 (2): 323–374.

Djankov, S., La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. 2002. The regulation of entry. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118 (2): 1–37.

Feenstra, R., & Hanson, G. 2005. Ownership and control in outsourcing to China: Estimating the property-rights theory of the firm. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120 (2): 729–761.

Gatignon, H., & Anderson, E. 1988. The multinational corporation's degree of control over foreign subsidiaries: an empirical test of a transaction cost explanation. Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, 4 (2): 305–336.

Glaeser, E., Johnson, S., & Shleifer, A. 2001. Coase versus the Coasians. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116 (3): 853–899.

Gomes-Casseres, B. 1989. Ownership structures of foreign subsidies: theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 11 (1): 1–25.

Grossman, S., & Hart, O. 1986. The costs and benefits of ownership: A theory of vertical and lateral integration. Journal of Political Economy, 94 (4): 691–719.

Hart, O., & Moore, J. 1990. Property rights and the nature of the firm. Journal of Political Economy, 98 (6): 1119–1158.

Holmstrom, B. 1999. The firm as a subeconomy. Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, 15 (1): 74–102.

Holmstrom, B., & Milgrom, P. 1994. The firm as an incentive system. American Economic Review, 84 (2): 972–991.

Holmstrom, B., & Roberts, J. 1998. The boundaries of the firm revisited. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 12 (4): 73–94.

Jarrell, G. A., & Poulsen, A. B. 1989. Stock trading before the announcement of tender offers: Insider trading or market anticipation? Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, 5 (2): 225–248.

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. 1976. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3 (4): 305–360.

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. 1995. Specific and general knowledge and organizational structure. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 8 (2): 4–18.

Jensen, M. C., & Ruback, R. 1983. The market for corporate control. Journal of Financial Economics, 11 (1–4): 5–50.

Johnson, S., La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. 2000. Tunneling. American Economic Review, 90 (2): 22–27.

Kali, R. 2002. Contractual governance, business groups and transition. Economics of Transition, 10 (2): 255–272.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Zoido-Lobaton, P. 1999. Aggregating governance indicators, Policy Research Working Paper no. 2195, The World Bank, Washington, DC.

Klein, B., Crawford, R. G., & Alchian, A. 1978. Vertical integration, appropriable rents, and the competitive contracting process. Journal of Law and Economics, 21 (2): 297–326.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. 1997. Legal determinants of external finance. Journal of Finance, 52 (2): 1131–1150.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. 1998. Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy, 106 (6): 1113–1155.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. 2000. Investor protection and corporate governance. Journal of Financial Economics, 58 (1–2): 3–27.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. 2002. Investor protection and corporate valuation. Journal of Finance, 57 (3): 1147–1170.

McConnell, J. J., & Nantell, T. J. 1985. Corporate combinations and common stock returns: The case of joint ventures. Journal of Finance, 40 (2): 519–536.

Moeller, S. B., & Schlingemann, F. 2005. Global diversification and bidder gains: A comparison between cross-border and domestic acquisitions. Journal of Banking and Finance, 29 (3): 533–564.

Montgomery, C. 1994. Corporate diversification. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 8 (3): 163–178.

Penrose, E. 1959. The theory of the growth of the firm. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Prahalad, C.K., & Hamel, G. 1990. The core competence of the corporation. Harvard Business Review, 68 (3): 79–90.

Rajan, R., & Zingales, L. 1998a. Financial dependence and growth. American Economic Review, 88 (3): 559–586.

Rajan, R., & Zingales, L. 1998b. Power in a theory of the firm. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113 (2): 387–432.

Rajan, R., & Zingales, Z. 2001. The firm as a dedicated hierarchy: A theory of the origins and growth of firms. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116 (3): 805–851.

Rajan, R., Servaes, H., & Zingales, L. 2000. The cost of diversity: The diversification discount and inefficient investment. Journal of Finance, 55 (1): 35–80.

Rossi, S., & Volpin, P. 2004. Cross-country determinants of mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Financial Economics, 74 (2): 277–304.

Shin, H., & Stulz, R. 1998. Are internal capital markets efficient? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113 (2): 531–552.

Simon, H. 1951. A formal theory of the employment relationship. Econometrica, 19 (3): 293–305.

Smith, R. L., & Kim, J. H. 1994. The combined effects of free cash flow and financial slack on bidder and target stock returns. Journal of Business, 67 (2): 281–310.

Wernerfelt, B. 1984. A resource based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5 (2): 171–180.

Williamson, O. E. 1975. Markets and hierarchies: Analysis and antitrust implications. New York: Free Press.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge helpful comments by Bruce Blonigen (Departmental Editor), two anonymous referees, and Karl Lins, as well as seminar participants at the 2006 Financial Management Association conference in Salt Lake City. Tomas Jandik would like to thank the Summer Research Grant Program at the Walton College of Business for support to undertake this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Accepted by Bruce Blonigen, Departmental Editor, 3 March 2008. This paper has been with the authors for one revision.

Appendix

Appendix

Case 1

When the reneging constraint binds, we have

or

or

where

The solution to the optimization is the largest value of b j ∈[0, 1] that satisfies the quadratic equation, yielding

Thus b j ** increases with var(μ).

Case 2

When the reneging constraint binds, we have

where

or

or

where

The solution to the optimization is the largest value of b j ∈[0, 1] that satisfies the quadratic equation, yielding

Since G decreases with r, and b j ** increases with G, b j ** decreases with r. As H decreases with w and tx, and b j ** increases with H, b j ** decreases with w and tx. And since k increases with var(μ), b j ** decreases with var(μ).

Thus

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jandik, T., Kali, R. Legal systems, information asymmetry, and firm boundaries: Cross-border choices to diversify through mergers, joint ventures, or strategic alliances. J Int Bus Stud 40, 578–599 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2008.95

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2008.95