Abstract

Increasingly online retailers are allowing their customers to leave online feedback on the products or services they offer. There have been limited efforts in understanding the mechanism through which such online feedback affect consumers’ purchase decisions. In this article, we report an empirical study on the informational influence of online customer feedback (OCF), that is, how consumers decide to integrate the information content of the feedback into their purchase decisions. We argue that the perceived usefulness of OCF plays a central role in this process, as the effects of prior experience with OCF, consumer trust toward OCF, and perceived importance of OCF work through perceived usefulness. Hypotheses derived from our research model were supported with survey data, and results suggest new ways to improve the design of OCF systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

To be customer driven and market oriented1, 2, 3, 4 is the key to gain competitive advantages for today's retailers. The advances of information technologies and the widespread of the Internet have transformed the retail industries. They gave birth to retailers who specialize in online channels. They also allowed many traditional retailers to provide online channels for customers (that is, bricks-and-clicks), and studies show that multi-channels appeal to customers.5 The crowded online marketspace spurs fierce competitions between online retailers, which drive their further adoption of new technologies to help gain and maintain market share. Increasingly, retailers are allowing customers and visitors to their websites to provide feedback of the products or services offered on their websites and making the feedback available to potential customers. During a study of the Top 100 retailers (www.stores.org) in spring 2007 (in fact, there were 134 retailers in our study because some of them are groups of retailers), we found that 57 per cent of the top retailers provided online shopping channels. Among these retailers, 22 per cent (N=17) allowed online customer feedback (OCF). A similar study of the top retailers 2 years later showed that 62 per cent of the top retailers had online shopping channels and 56 per cent (N=35) of the online channels had allowed OCF. In a little over 2 years, while stores with online channels increased by about 9 per cent, the numbers of stores with OCF more than doubled. Such OCF included both verbal comments and numerical ratings, with some including numerical ratings along several store-chosen dimensions.

Previous studies suggested that consumers indeed use OCF and the information contained in the feedback does affect their purchase decision making.6 With as many as 62 per cent of the consumers having looked at least once at online feedback before making a decision,7 we need to understand more of the mechanisms underlying OCF's influences on consumers. We report such an effort in this article. Our study takes the perspective of informational influence and we argue that the perceived usefulness of OCF plays a central role in this process. We further explore the antecedents of perceived usefulness. A theoretical framework is proposed and a set of hypotheses are developed and tested with survey data. We conclude the article with a discussion of the findings and their implications as well as suggestions for future research.

LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

Many studies have focused on a special type of OCF offered through Online Reputation Systems. Such feedback systems allow traders to rate each other on their performances. Over time, trustworthiness of individual traders can be evaluated based on the accumulated records of the ratings. Companies in Consumer-to-Consumer (C-to-C) e-business such as eBay use such systems to promote honest behavior and to facilitate transactions among traders. Research shows that online reputation systems can be an effective tool for reputation building and can promote trust and cooperation in a seemingly risky C-to-C e-business environment: sellers with better ratings can commend premium prices.8, 9, 10, 11 In this study, we focus on a different type of OCF, feedback that allows visitors and customers of an online retailer to offer their personal insights a products or services offered by online retailers.

OCF and informational influence

OCF is a special type of information service that online retailers extend to their customers. It differs from other types of information services in that the content is generated by customers, not the retailers. In this sense, it resembles traditional ‘word of mouth (WOM)’. Research in consumer behavior has long established the importance of WOM: This form of interpersonal communication is often the most important and trusted source for product/service information and greatly affects potential customers’ preferences and choices.12, 13, 14

OCF differs from traditional WOM in two aspects.6 First, whereas traditional WOM are informal communications typically spread between closely knitted consumers, OCF allows consumers who do not know each other in the real life to share their viewpoints on a product or service. The strength of the ties between the consumers who participate in exchanging OCF is much weaker than that of the ties between the consumers who exchange traditional WOM.15 Second, whereas traditional WOM is typically transient and has to be relayed from one consumer to another face-to-face, OCF is typically computer-mediated and is thus persistent.16 It has high referability in that it can be accessed by a large number of people and over a long period of time after it becomes available online.6 On the one hand, through OCF consumers are exposed to a potentially large amount of diverse and possibly high-quality information that is not available otherwise.17 The high referability of OCF also makes it possible for OCF to have widespread and long-lasting effects. On the other hand, trust between parties who are involved in spreading the traditional WOM underlies the effectiveness of WOM. The weak ties between the readers and contributors of OCF could compromise the formation of such trust,18 reducing the effectiveness of OCF.

Previous research showed that consumers do use OCF to inform their purchase decision making: A study in 2007 found that 62 per cent of the consumers have looked at least once at online feedback before making a decision.7 Apparently, by reading OCF, consumers acquire information that aids their purchase decision making.6 Sussman and Siegal19 regarded the assessment and adoption of acquired information a form of informational influence, whereby individuals are influenced by the received information to take the position advocated by the acquired information. Following them, we refer the informational influence of OCF to the processing of information content of OCF and the integration of the information into purchase decisions by consumers. In this study, we explore the informational influence of OCF by investigating how consumers’ perceptions of OCF affect information adoption, the consumers’ integration of the information content of the OCF into their purchase decisions. In line with Sussman and Siegal,19 we argue that the perceived usefulness of OCF plays a central role in its informational influence, and we explore a few factors that can be the antecedents of the perceived usefulness.

Perceived usefulness of OCF

The construct of perceived usefulness is pivotal in the popular Technology Acceptance Model (TAM),20 which describes relationships between the perceptions of an information technology (IT) and its acceptance by the users. Within the TAM, perceived usefulness refers to ‘the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would enhance his or her job performance’ (p. 320).20 It represents users’ expectations of the potential benefits from using an IT. Numerous studies have repeatedly confirmed the important role perceived usefulness plays in promoting the acceptance of an IT by generating a positive attitude toward using the technology, enhancing users’ intentions to use the technology, and subsequently increasing the actual usage of the technology.21

Sussman and Siegal19 extended perceived usefulness to the domain of knowledge transfer. Their study on how people treat received advices showed that perceived usefulness of the advices plays a central role in their adoption: the processing of a piece of received advice led first to the judgment of how useful the information embedded in the advice is to solving one's problem at hand. The perceived usefulness in turn affects the degree to which the information is adopted. In this way, perceived usefulness mediates between information processing and the adoption of the information.

In this study, we apply perceived usefulness to the study of OCF, and refer it to the degree to which consumers believe they can benefit from the information embedded in the OCF. In this sense, perceived usefulness captures the utilitarian motivation for a consumer to be influenced by OCF: the more the customers regard the OCF as useful, the more likely they are to be influenced by the information contained in OCF and to make purchase decisions that are in the same direction as advocated by the OCF. This is consistent with the information motives underlying customers’ use of online WOM previously identified by Schindler and Bickart.6 To the extent that consumers use OCF to provide input to their purchase decision making, we propose:

Hypothesis 1:

-

A higher level of perceived usefulness of OCF by consumers is associated with a higher level of information adoption by consumers.

Given the importance of the information motive observed by Schindler and Bickart6 and following the arguments by Sussman and Siegal,19 we also propose that the perceived usefulness plays a central role in the informational influence of OCF as well. We believe that the effects of a few other factors on the eventual information adoption of OCF are through the perceived usefulness of OCF. These factors include prior experience with OCF, perceived importance of OCF and trust toward OCF, which are discussed in turn below.

Prior experience with OCF

OCF is by no means novel to consumers. The Internet has long allowed consumers to exchange information on products or services in ways that are not sponsored by particular manufacturers, service providers or retailers. Even before the widespread of the web, technologies such as UseNet newsgroups were used for such purposes.22 There are now websites specializing in publishing OCF (for example, epinion.com and tripadvisor.com). Some largest online retailers such as Amazon.com have also adopted OCF for long. Explorative studies confirmed that many consumers had had some experience using OCF or similar consumer-generated information.6, 7

Prior experience with OCF could affect consumers’ perception of OCF. People learn from prior experience, and the knowledge they gain through prior experience is more accessible and more salient in their memories to affect their perceptions.23 If consumers formed a favorable perception of the usefulness of the OCF in their prior experience – which is likely as suggested by previous studies with OCF,6 this perception is likely to be carried over into consumers’ next use of OCF, and predispose consumers to perceive OCF as useful.

Consumers who have more experience with OCF may also be better at using OCF. Research in Information Technologies (IT) acceptance indicated that more experienced users tended to perceive an IT to be more useful than users that were less experienced.24 One possible explanation for this is that as users get more experience with an IT, they learn how to use the IT to its strength.25 As more effective use of the IT leads to higher productivity and better work performance, the perception of the usefulness of the IT becomes more favorable. Similarly, the use of OCF is also a learning experience in which consumers learn how to effectively and efficiently evaluate the information offered by OCF, for example how to tell biased or even deceptive comments from truthful feedback.6 The more experience consumers get using OCF, the better they get at evaluating OCF, and the more favorable they will perceive the usefulness of OCF. Thus we posit:

Hypothesis 2:

-

A higher level of prior experience with OCF by consumers is associated with a higher level of perceived usefulness of OCF by consumers.

Perceived importance of OCF

Perceived importance is a powerful motivator for people to take certain actions:26, 27 Students who consider Math important tend to perform better in Math;28 trainees who consider training programs important are more motivated and do better in the training programs;29 accounting students who consider it important to make ethical decisions are more likely to make ethical decisions;30 and workers who consider it important to use information technologies are more likely to actually use information technologies.31 In similar ways, consumers who consider OCF important should be more motivated to attend to and incorporate OCF when they make their purchase decisions.

Larcker and Lessig defined perceived importance of information as ‘the quality that causes a particular information set to acquire relevance to a decision maker’ and the extent to which ‘the information items are a necessary input for task accomplishment’ (p. 123). 32 The necessity of the information for decision making makes the information more useful.32 Thus, if consumers believe that information contained in OCF is important and necessary for them to make their purchase decisions, likely they will consider OCF as useful. Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 3:

-

A higher level of perceived importance of OCF by consumers is associated with a higher level of perceived usefulness of OCF by consumers.

Trust toward OCF

Trust is a much-studied factor in both off-line and online businesses.33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 In a recent study, Gefen et al39 studied how trust toward a vendor affect consumers’ perception of purchasing from the vendor's site. They argued that trust toward a vendor leads to a higher level of perceived usefulness of buying from the vendor because the customers believe that the vendor is less likely to act opportunistically, and hence more likely to fulfill the expected benefits from buying from the vendor. Trust is also an important factor in information sharing.40, 41 An information recipient who trusts the source of the information tends to assess the received information more favorably and is more likely to act on it.19, 42

In the context of OCF, the trust toward OCF can outweigh the trust toward the vendor or the trust toward the information source. After all, the content of OCF is contributed not by the vendors, but by the customers and visitors to the vendors’ website. With traditional WOM, the trust between source and recipient of the information results from previous interactions between them. The weak ties between the readers and contributors of OCF, however, prevent the similar development of the trusting relationship between them. Instead, consumers often must assume the trustworthiness of the contributors, presupposing that the contributors cannot or do not profit from disseminating untruthful information.18 Under such circumstance, the consumers likely are more concerned with the information embedded in the OCF than with the vendor or the contributors of OCF. The more the consumers trust the OCF they use, they more useful they will think the OCF is, because they are readier to be influenced by it. Therefore:

Hypothesis 4:

-

A higher level or trust toward OCF by consumers is associated with a higher level of perceived usefulness of OCF by consumers.

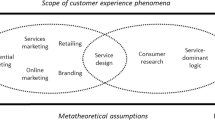

Figure 1 presents our research model graphically.

RESEARCH METHODS

We used a survey to empirically test our research model. The scales for the survey were adapted from those used in previous studies except those for perceived importance, which were self-developed, and prior experience with OCF, which we measured by asking survey respondents how many times they had shopped an online store with OCF during the 3 months before the survey. More specifically, trust toward OCF items were adapted from Dahlstrom and Nygaard,43 Moorman et al44 and Osterhus.45 The items for information adoption were from Dabholkar46 and Lacher and Mizerski,47 and those for perceived usefulness of OCF were adapted from Davis.20 All measures use 1–7 scale with 1 being unfavorable (such as ‘Very unimportant’ or ‘Strongly disagree’), 4 being neutral and 7 being favorable (such as ‘Very important’ or ‘Strongly agree’). A pretest and a pilot study were conducted before the measures were finalized (see Appendix for the measure items).

The survey was conducted using a face-to-face interview approach. The interviewers were trained under the guidance of one of the authors. The survey was conducted in a northeastern metropolitan area of the United States. A two-step sampling method was used in this study: the respondents (1) were evenly distributed in different communities (that is, cities and towns), and (2) lived in different streets of the each community. To ensure the data quality, the interviewers were required to write interview logs on where, when, how the interviews were conducted. Three hundred and fifty survey interviews were planned. After deleting the uncompleted and unusable surveys, we got 295 completed surveys back, which resulted in a satisfactory response rate of 84.3 per cent. This face-to-face approach is more costly than some other approaches, but it ensures the response rate and, more importantly, the quality of the collected data. Moreover, when respondents have questions on the terms or need some further explanations, the interviewers are right there to help them.

RESULTS

Most of our respondents are young, single adults: almost 60 per cent of them reported themselves as younger than 25 years old (N=168) and about 75 per cent unmarried (N=222). One hundred and twenty-nine of the 295 respondents were men, and about two-thirds of the respondents were White (N=196). About half of our respondents (N=150) received at least 4-year college education. A third of the respondents (N=99) did not shop in an online store offering OCF in the 3 months before the survey.

Although ANOVA tests of measurement items on the demographic variables showed a few significant differences, adding the demographic variables as control variables to the research model described in Figure 1 does not change the results of the indicator loadings and path coefficients. For the interest of a parsimonious model and a clear presentation and explanation, we report here only the results from testing the model without including the demographic variables.

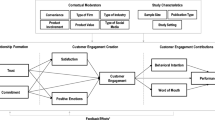

The measurement models and the hypothesized structural paths are estimated simultaneously using maximum likelihood estimation techniques in LISREL 8.70, and the results were shown in Figure 2. All the indicator loadings are significant at P<0.001 level, showing strong evidence of convergent validity of the measures. Discriminant validity is assessed with the procedure recommended by Fornell and Larcker.48 Each pair of constructs passes the test in the procedure. The shared variance between any two constructs is smaller than the shared variance between each construct and its indicators. Therefore, the discriminant validity is achieved for all the measures. Although the χ2 fit index for the model is significant (λ2=81.82, df=29 and P=0.000), other overall model fit indexes are in the acceptable ranges (GFI, AGFI, IFI, CFI, and NFI are all above the 0.90 level, RMSEA=0.079, and both RMR and SRMR are smaller than 0.10).

We tested the hypotheses proposed earlier by examining the significance of the path coefficients of the estimated structural model (Figure 2). Hypothesis 1 hypothesizes that when users perceive OCF to be useful, they are more likely to adopt the information embedded in OCF. The path coefficient between perceived usefulness and information adoption was positive and highly significant (β=0.70, P<0.001), strongly supporting Hypothesis 1. Hypotheses 2–4 are about the proposed antecedents of perceived usefulness of OCF. They posit that prior experience with OCF, trust toward OCF and perceived importance of OCF are positively associated with perceived usefulness of OCF. All path coefficients between the proposed antecedents and perceived usefulness are positive and significant at P<0.01 level at least. Thus Hypotheses 2–4 are supported too.

To further explore the relationships between the proposed antecedents of perceived usefulness and final information adoption, we added to the structural model (Figure 2) direct links from its antecedents to information adoption. The analysis showed that none of the links was significant, which suggests that none of the hypothesized antecedents affect information adoption directly. Rather, they influence information adoption indirectly through perceived usefulness. This explorative analysis confirmed that, just as we expected, consumers’ perception of how useful OCF plays a central role in their decisions on whether to adopt the information embedded in OCF or not.

DISCUSSIONS

In this article, we reported a study on the informational influence of OCF. We argued that prior experience with OCF, perceived importance of OCF and trust toward OCF affect perceived usefulness of OCF, which in turn affects information adoption of OCF. Survey data were collected to empirically test the research model, and the results are supportive of what we have hypothesized.

Findings

One of the very interesting findings of this study is the strong relationship between perceived usefulness of OCF and the information adoption of OCF (β=0.70, P<0.001). This suggests that for OCF to have an impact on consumers’ purchase decision making, it has to be perceived as useful by the consumers. This is consistent with previous findings made by Sussman and Siegal19 when studying informational influence of received advices. It also quantitatively confirms Schindler and Bickart's observation of the informational motive of consumers who use OCF.6

All three antecedents we identified appear to affect perceived usefulness of OCF positively. First of all, the more experienced consumers are with using OCF, the more likely they perceive OCF as useful (β=0.14, P<0.01). We argued that this was because consumers learn from their own experience with OCF. Our argument assumed that consumers’ prior experience with OCF was positive, which appeared to be the case in this study just like in other studies.6

The second antecedent we studied is trust toward OCF. Not surprisingly, trust toward OCF is strongly associated with perceived usefulness of OCF (β=0.55, P<0.001). This highly significant finding highlighted that distrust toward OCF could prevent consumers from taking advantages of OCF. With traditional WOM, the trust established between the consumers and the source of WOM help to convince the consumers of the validity of the WOM. As we have discussed, the ties between the consumers and the authors of OCF are typically weak. Exactly how consumers develop trust toward OCF from strangers can be an interesting topic for future research.

Finally, there is a strong relationship between perceived importance and perceived usefulness of OCF (β=0.48, P<0.001). Perceived importance motivates consumers to attend to OCF and to take advantage of OCF. As studies indicate that more consumers are attributing more importance to OCF,6 this finding is encouraging for online retailers who offer OCF or who are planning to offer OCF on their websites.

Limitations and contributions

There are some limitations for this research. First, for the purpose of this explorative study, we chose to limit our research scope to subjective experience and perceptions of OCF. More objective methods such as experiments might be helpful in obtaining more conclusive results regarding the causal relationships between the studied constructs. Second, our sample is collected within a northeastern metropolitan area in the United States. Our survey respondents may represent only the local population (that is, mostly young, unmarried and educated) but not the overall national population. A larger sample size and respondents from other areas would be desirable to ensure the generalizability of our findings. Finally, some of the measures in this study are self-developed, others adapted. Although we pilot-tested them and the results of testing the measurement models are satisfactory, further refinement may be needed. Further research should take above limitation into consideration.

Moreover, as most other studies in OCF, we did not specifically address the valence of OCF in this study. One may argue that this study, as well as many other studies in OCF, implicitly assumes that OCF is objective and fair. As the popularity of OCF increases and its benefits toward businesses become better known, people with different agendas are bound to take advantage of biased OCF, or even manipulate OCF for various goals.49 To what extent can biased OCF affect consumers? How can consumers negate biased or manipulated OCF? These can be interesting research topics for future studies in OCF.

Despite all these limitations, our study makes a few theoretical contributions. Contributing OCF is a typical consumer post-purchase behavior and directly shows whether the consumer is satisfied or dissatisfied, which is significantly linked to the customer complaining behavior or customer loyalty.50 As the electronic form of Word-of-Mouth, OCF has been shown to substantially affect consumer purchase decision.6, 7, 51 In fact, OCF can have great impacts on firms’ strategy formation.52 It is imperative that we understand more about how OCF works. From the informational influence perspective, our study builds on the previous research on consumer-generated content.6 It explores the antecedents and consequence of the perceived usefulness of OCF for the first time, thus contributing to the post-purchase behavior, electronic Word-of-Mouth, and the connected consumer literature directly.

Practical recommendations

Practically, the findings from our study offer a few recommendations for online retailers on how to design OCF system to make it easier for consumers to take advantage of OCF, which in turn could be used to attract consumers to the retailers’ websites. Because perceived usefulness played a central role in the informational influence of OCF, OCF system should be designed to make it easier for consumers to evaluate the usefulness of OCF. For example, many websites now allow consumers to evaluate a piece of OCF as helpful or not helpful, or even to rate OCF. Intuitively, such OCF of OCF could help consumers to decide how useful the original OCF is, making it easier for consumers to take advantage of the information content of OCF.

OCF system can also incorporate features to help consumers to develop trust toward OCF. For example, some retailers now indicate on their system that whether a piece of OCF on a product is from an authenticated customer who has previously purchased the product or service. Features like this may help promote consumers’ trust toward OCF. The effectiveness of these designs can be intriguing topics for future studies.

In addition, this study confirmed the importance of OCF to consumers. Because consumers are indeed influenced by OCF, firms could take advantage of OCF systems too by implementing analytical system behind the OCF system. With the numerical rating data and the verbal comments, the analytical system could conduct both statistical analysis and content analysis. From the analytical system, firms with OCF system could find the patterns of customers’ feedbacks by product categories, service types, geographic regions, customer demographic and psychographic profiles, and nature of the feedbacks, which would be critical for the firms’ long-term customer relationship management.

Conclusions

In this article, we report an empirical study on the informational influence of OCF. We developed a research model focusing on perceived usefulness of OCF, with prior experience, perceived importance and trust as the antecedents and informational adoption of OCF by consumers as the consequence of perceived usefulness. Survey data were collected from real consumers to test the model.

The results lent strong support to our research model and hypotheses, indicating that consumers will adopt information from OCF when they perceive the OCF as useful. Further, how useful consumers perceive OCF to be depends on their prior experience with OCF, their trust toward OCF and how important they perceive OCF is. Overall, this study indicates that consumers highly value the usefulness of OCF when they decide whether to adopt the information embedded in OCF, and it sheds some light on how consumers evaluate the usefulness of OCF.

References

Jaworski, B.J. and Kohli, A.K. (1993) Market orientation: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Marketing 57 (3): 53–70.

Moorman, C. and Rust, R.T. (1999) The role of marketing. Journal of Marketing 63 (4): 180–197.

Narver, J.C. and Slater, S.F. (1990) The effect of a market orientation on business profitability. Journal of Marketing 54 (4): 20–35.

Day, G.S. (1994) The capabilities of market-driven organizations. Journal of Marketing 58 (4): 37–52.

Bendoly, E., Blocher, J.D., Bretthauer, K.M., Krishnan, S. and Venkataramanan, M.A. (2005) Online/in-store integration and customer retention. Journal of Service Research 7 (4): 313–327.

Schindler, R.M. and Bickart, B. (2005) Published word of mouth: Referable, consumer-generated information on the internet. In: C.P. Haugtvedt (ed.) Online Consumer Psychology: Understanding and Influencing Consumer Behavior in the Virtual World. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 35–61.

Byrnes, N. (2007) More clicks at the bricks. BusinessWeek 17 December: pp. 50–52.

Dellarocas, C. (2003) The digitization of word of mouth: Promise and challenges of online feedback mechanisms. Management Science 49 (10): 1407–1424.

McDonald, C.G. and Slawson Jr, V.C. (2002) Reputation in an internet auction market. Economic Inquiry 40 (4): 633–650.

Melnik, M.I. and Alm, J. (2002) Does a seller's eCommerce reputation matter? Evidence from eBay auctions. Journal of Industrial Economics 50 (3): 337–349.

Resnick, P. and Zeckhauser, R. (2000) Reputation systems. Communications of the ACM 43 (12): 45.

Brooks, R.C. (1957) ‘Word-of-mouse’ advertising in selling new products. Journal of Marketing 22 (2): 154–161.

Buttle, F.A. (1998) Word of mouth: Understanding and managing referral marketing. Journal of Strategic Marketing 6 (3): 241–254.

Dye, R. (2000) The buzz on buzz. Harvard Business Review 78 (6): 139–146.

Granovetter, M. (1973) The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology 78 (6): 1360–1380.

Erickson, T., Smith, D.N., Kellogg, W.A., Laff, M., Richards, J.T. and Bradner, E. (eds.) (1999) Socially translucent systems: Social proxies, persistent conversation, and the design of ‘Babble’. Proceedings of CHI'99’ Pittsburgh, PA. New York: ACM Press.

Constant, D., Sproull, L. and Kiesler, S. (1996) The kindness of strangers: The usefulness of electronic weak ties for technical advice. Organization Science 7 (2): 119–135.

Zhang, W. (ed.) (2007) Trust in electronic networks of practice: An integrative model. Proceedings of the Third Communities and Technologies Conference. Lansing, MI. Springer Verlag: London.

Sussman, S.W. and Siegal, W.S. (2003) Informational influence in organizations: An integrated approach to knowledge adoption. Information Systems Research 14 (1): 47–65.

Davis, F.D. (1989) Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly 13 (3): 319–339.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M.G., Davis, G.B. and Davis, F.D. (2003) User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly 27 (3): 425–478.

Tsang, A.S.L. and Zhou, N. (2005) Newsgroup participants as opinion leaders and seekers in online and offline communication environments. Journal of Business Research 58 (9): 1186–1193.

Taylor, S. and Todd, P.A. (1995) Assessing IT usage: The role of prior experience. MIS Quarterly 19 (4): 561–570.

Karahanna, E., Straub, D.W. and Chervany, N.L. (1999) Information technology adoption across time: A cross-sectional comparison of pre-adoption and post-adoption beliefs. MIS Quarterly 23 (2): 183–213.

Carlson, J.R. and Zmud, R.W. (1999) Channel expansion theory and the experiential nature of media richness perceptions. Academy of Management Journal 42 (2): 153–170.

Eccles, J.S. and Wigfield, A. (2002) Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology 53 (1): 109–132.

Chai, S., Bagchi-Sen, S., Morrell, C., Rao, H.R. and Upadhyaya, S. (2006) Role of perceived importance of information security: An exploratory study of middle school children's information security behavior. Journal of Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology 3: 127–135.

Pajares, F. and Graham, L. (1999) Self-efficacy, motivation constructs, and mathematics performance of entering middle school students. Contemporary Educational Psychology 24 (2): 124–139.

Tsai, W.-C. and Tai, W.-T. (2003) Perceived importance as a mediator of the relationship between training assignment and training motivation. Personnel Review 32 (1–2): 151–163.

Guffey, D.M. and McCartney, M.W. (2008) The perceived importance of an ethical issue as a determinant of ethical decision-making for accounting students in an academic setting. Accounting Education 17 (3): 327–348.

Zhang, W. and Gutierrez, O. (2007) Information technology acceptance in the social services sector context: An exploration. Social Work 52 (3): 221–231.

Larcker, D.F. and Lessig, V.P. (1980) Perceived usefulness of information: A psychometric examination. Decision Sciences 11 (1): 121–134.

Doney, P.M. and Cannon, J.P. (1997) An examination of the nature of trust in buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing 61 (2): 35.

Morgan, R.M. and Hunt, S.D. (1994) The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing 58 (3): 20–38.

Garbarino, E. and Johnson, M.S. (1999) The different roles of satisfaction, trust, and commitment in customer relationships. Journal of Marketing 63 (2): 70–87.

Sirdeshmukh, D., Singh, J. and Sabol, B. (2002) Consumer trust, value, and loyalty in relational exchanges. Journal of Marketing 66 (1): 15–37.

Grabner-Kraeuter, S. (2002) The role of consumers’ trust in online-shopping. Journal of Business Ethics 39 (1/2): 43–50.

Pavlou, P.A. (2003) Consumer acceptance of electronic commerce: Integrating trust and risk with the technology acceptance model. International Journal of Electronic Commerce 7 (3): 101–134.

Gefen, D., Karahanna, E. and Straub, D.W. (2003) Inexperience and experience with online stores: The importance of TAM and trust. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 50 (3): 307–321.

Levin, D.Z. and Cross, R. (2004) The strength of weak ties you can trust: The mediating role of trust in effective knowledge transfer. Management Science 50 (11): 1477–1490.

Szulanski, G., Cappetta, R. and Jensen, R.J. (2004) When and how trustworthiness matters: Knowledge transfer and the moderating effect of causal ambiguity. Organization Science 15 (5): 600–613.

Zhang, W. and Watts, S. (2008) Capitalizing on content: Information adoption in two online communities. Journal of Association of Information Systems 9 (2): 73–94.

Dahlstrom, R. and Nygaard, A. (1995) An exploratory investigation of interpersonal trust in new and mature market economies. Journal of Retailing 71 (4): 339–361.

Moorman, C., Zaltman, G. and Deshpande, R. (1992) Relationships between providers and users of market research: The dynamics of trust within and between organizations. Journal of Marketing Research 29 (3): 314–328.

Osterhus, T.L. (1997) Pro-social consumer influence strategies: When and how do they work? Journal of Marketing 61 (4): 16–29.

Dabholkar, P.A. (1994) Technology-based service delivery: A classification scheme for developing marketing strategies. Advances in Services Marketing and Management 3: 241–271.

Lacher, K.T. and Mizerski, R. (1994) An exploratory study of the responses and relationships involved in the evaluation of, and in the intention to purchase new rock music. Journal of Consumer Research 21 (2): 366–380.

Fornell, C. and Larcker, D.F. (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 18 (1): 39–50.

DeLorenzo, I. (2010) Everyone's a critic: Yelp and other online sites and their cadre of amateurs have sent nervous ripples through the restaurant world. Boston Globe 2 June, Sect. G.19.

Luo, X. and Homburg, C. (2007) Neglected outcomes of customer satisfaction. Journal of Marketing 71 (2): 133–149.

Liu, Y. (2006) Word-of-mouth for movies: Its dynamics and impact on box office revenue. Journal of Marketing 70 (3): 74–89.

Prahalad, C.K. and Ramaswamy, V. (2002) The co-creation connection. Strategy and Business 27: 1–12.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Faculty Scholarship Award from the College of Management, University of Massachusetts Boston, China NSF, and Leadi Institute of Dalian University of Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

Measurement items

Information adoption of OCF

If the reviews and ratings were very positive, how likely would you be to purchase the product you are looking for (1=very unlikely and 7=very likely)?

Perceived importance of OCF

How important is the following information to you when you shop online? ((1=Very unimportant, 4=Neutral and 7=Very important).

-

Previous customers’ verbal reviews of the product

-

Previous customers’ overall numerical rating

-

The numerical ratings for major product dimensions (such as quality, usefulness, ease of use and so on).

Perceived usefulness of OCF

Please indicate your opinion on the following statements: (1=Strongly disagree, 4=Neutral and 7=Strongly agree).

-

OCF reviews are useful

Based on your online shopping experience, how helpful was the OCF system (that is, customer verbal or numerical reviews) in your purchase decision making (1=Not at all and 7=Very)?

Prior experience with OCF

How many times have you shopped in an online store that provides customer feedback in the last 3 months? ___ 0, ___ 1–2, ___ 3–4, ___ more than 4.

Trust toward OCF

Please indicate your opinion on the following statements: (1=Strongly disagree, 4=Neutral and 7=Strongly agree).

-

I trust the verbal reviews

-

I trust the overall numerical rating

-

I trust the numerical ratings for major product dimensions (such as quality, usefulness, ease of use and so on).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, R., Zhang, W. Informational influence of online customer feedback: An empirical study. J Database Mark Cust Strategy Manag 17, 120–131 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1057/dbm.2010.11

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/dbm.2010.11