Abstract

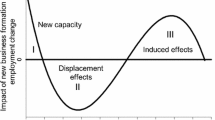

This study documents that the survival of start-ups is central in explaining the relationship between entry and regional employment growth. Distinguishing between start-ups according to the period of their survival shows that the positive effect of new business formation on employment growth is mainly driven by those new businesses that are strong enough to remain in the market for a certain period of time. This result is especially pronounced for the relationship between the surviving start-ups and employment growth in incumbent businesses indicating that there are significantly positive indirect effects of new business formation on regional development. We draw conclusions for policy and make suggestions for further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Indeed, entirely different results are found if, for example, the relationship between the level of start-ups and subsequent employment change is analyzed at the level of regions instead of at the level of industries (see Fritsch 1996). Therefore, geographical units of observation are much better suited for such an analysis than are industries.

In our data, new businesses are recorded at the time when they hire their first employee. Hence, a number of those businesses that are started without any employee but hire someone later on are recorded in that later year. Unfortunately, those start-ups that never have an employee, the solo-entrepreneurs, are not recorded in our data. Although it is known that this type of entrepreneurship has become more important in Germany during the 1990s (Boegenhold and Fachinger 2010), there is no information about solo-entrepreneurship available for smaller regional units such as planning regions. Although we cannot say anything in detail about the regional distribution of solo-entrepreneurs, we expect that the variables for regional industry structure, time dummies, and the regional fixed effects in our empirical model should prevent any significant distortion of the results caused by their omission. Given that these firms have no employee, we assume that their direct effects may be rather small if not negligible.

Analyzing regional differences of the direct employment effect of new business formation, Fritsch and Schindele (2011) take the number of employees in a start-up cohort after a certain period of time (2 or 10 years, respectively) over regional employment in the year before the new businesses have been set up as indicator for the direct effects. This measure is, however, not appropriate for a comparison with the indirect effects of new business formation because the effect of a certain start-up cohort on incumbent employment can hardly be empirically isolated for two reasons. First, the indirect effects take a period of about 10 years before they become fully evident so that the effects of different start-up cohorts overlap. Second, regional start-up rates tend to be rather constant over time so that the start-up rate for a certain year may not differ much from the average rate calculated for a longer period of time. Comparing the number of jobs that have been created in the start-up cohorts of the previous 10 years and that still exist in year \(t=\) 0 with change of incumbent employment is inappropriate for the same reason. The average employment share of start-up cohorts of the previous 10 years in year \(t=\) 0 is 23.1 percent (median: 22.5 percent).

This is also the main reason why firms that are older than three and a half years are classified as representing established business ownership in the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM); see Reynolds et al. (2005).

All cross-model tests are based on results of seemingly unrelated estimations in order to account for cross-equation correlation.

Some studies separately analyze start-ups in manufacturing and those in the service sector (e.g., van Stel and Suddle 2008; Andersson and Noseleit 2011). Baptista and Preto (2011) perform analyses for knowledge-intensive service industries and compare the results with other sectors such as non-knowledge-intensive services.

The obvious reason why the vast majority of work on the effect of new business formation uses employment as an indicator of performance is data availability. Exemptions are Carree and Thurik (2008), who use GDP and labor productivity as dependent variables, and Thurik et al. (2008), who investigate the effect of self-employment and unemployment.

References

Aghion P, Blundell RW, Griffith R, Howitt P, Prantl S (2004) Entry and productivity growth: evidence from micro-level panel data. J Eur Econ Assoc 2:265–276

Aghion P, Blundell RW, Griffith R, Howitt P, Prantl S (2009) The effects of entry on incumbent innovation and productivity. Rev Econ Stat 91:20–32

Andersson M, Noseleit F (2011) Start-ups and employment growth—evidence from Sweden. Small Bus Econ 36:461–483

Audretsch DB (1995) Innovation and industry evolution. MIT Press, Cambridge

Audretsch DB, Fritsch M (2002) Growth regimes over time and space. Reg Stud 36:113–124

Baptista R, Preto MT (2011) New firm formation and employment growth: regional and business dynamics. Small Bus Econ 36:419–442

Birch DL (1981) Who creates jobs? Public Interest :3–14

Birch DL (1987) Job creation in America: how our smallest companies put the most people to work. Free Press, New York

Boegenhold D, Fachinger U (2010) Entrepreneurship and its regional development: do self-employment rations converge and does gender matter? In: Bonnet J , Garcia Perez De Lema D , Van Auken H (eds) The entrepreneurial society. Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 54–76

Brüderl J, Schüssler R (1990) Organizational mortality: the liabilities of newness and adolescence. Admin Sci Q 35:530–547

Carree M, Thurik R (2008) The lag structure of the impact of business ownership on economic performance in OECD countries. Small Bus Econ 30:101–110

Caves RE (1998) Industrial organization and new findings on the turnover and mobility of firms. J Econ Lit 36:1947–1982

Davis SJ, Haltiwanger JC, Schuh S (1996) Small business and job creation: dissecting the myth and reassessing the facts. Small Bus Econ 8:297–315

Disney R, Haskell J, Heden Y (2003) Restructuring and productivity growth in UK manufacturing. Econ J 113:666–694

Falck O (2007) Mayflies and long-distance runners: the effects of new business formation on industry growth. Appl Econ Lett 14:1919–1922

Falck O (2009) New business formation, growth, and the industry lifecycle. In: Cantner U , Gaffard J-L , Nesta L (eds) Schumpeterian perspectives on innovation, competition and growth. Springer, Heidelberg, pp 299–311

Federal Office for Building and Regional Planning (Bundesamt für Bauwesen und Raumordnung) (2003) Aktuelle Daten zur Entwicklung der Städte, Kreise und Gemeinden, vol 17. Federal Office for Building and Regional Planning, Bonn

Fritsch M (1996) Turbulence and growth in West-Germany: a comparison of evidence by regions and industries. Rev Ind Organ 11:231–251

Fritsch M (2013) New business formation and regional development—a survey and assessment of the evidence. In: Foundations and trends in entrepreneurship, vol 9

Fritsch M, Noseleit F (2012a) Investigating the anatomy of the employment effects of new business formation. Camb J Econ. doi:10.1093/cje/bes030

Fritsch M, Noseleit F (2012b) Indirect employment effects of new business formation across regions: the role of local market conditions. Papers in Regional Science

Fritsch M, Schindele Y (2011) The contribution of new businesses to regional employment—an empirical analysis. Econ Geogr 87:153–170

Fritsch M, Noseleit F, Schindele Y (2010) The direct and indirect effects of new businesses on regional employment: an empirical analysis. Int J Entrep Small Bus 10:49–64

Haltiwanger J, Jarmin RS, Miranda J (2010) Who creates jobs? Small vs. large vs. young. U.S. Census Bureau, Center for Economic Studies. CES, Washington, DC, pp 10–17

Horrell M, Litan R (2010) After inception: how enduring is job creation by startups? Kauffman Foundation, Kansan City

Klepper S (1996) Entry, exit, growth, and innovation over the product life cycle. Am Econ Rev 86:562–583

Kronthaler F (2005) Economic capability of East German regions: results of a cluster analysis. Reg Stud 39:739–750

Neumark D, Zhang J, Wall B (2006) Where the jobs are: business dynamics and employment growth. Acad Manag Perspect 20:79–94

Peneder M (2002) Industrial structure and aggregate growth. Struct Chang Econ Dyn 14:427–448

Redding SJ, Sturm DM (2008) The costs of remoteness: evidence from German division and reunification. Am Econ Rev 95:1766–1797

Reynolds PD et al (2005) Global entrepreneurship monitor: data collection design and implementation 1998–2003. Small Bus Econ 24:205–231

Schindele Y, Weyh A (2011) The Direct employment effects of new businesses in Germany revisited—an empirical investigation for 1976–2004. Small Bus Econ 36:353–363

Spengler A (2008) The establishment history panel. Schmollers Jahrbuch/J Appl Soc Sci Stud 128:501–509

Spletzer JR (2000) The contribution of establishment births and deaths to employment growth. J Bus Econ Stat 18:113–126

Stangler D, Kedrosky P (2010) Neutralism and entrepreneurship: the structural dynamics of startups, young firms and job creation. Kauffman Foundation, Kansas City

Südekum J (2008) Convergence of the skill composition across German regions. Reg Sci Urban Econ 38:148–159

Thurik RA, Carree MA, van Stel A, Audretsch DB (2008) Does self-employment reduce unemployment? J Bus Venturing 23:673–686

van Stel A, Suddle K (2008) The impact of new firm formation on regional development in the Netherlands. Small Bus Econ 30:31–47

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fritsch, M., Noseleit, F. Start-ups, long- and short-term survivors, and their contribution to employment growth. J Evol Econ 23, 719–733 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-012-0301-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-012-0301-5