Abstract

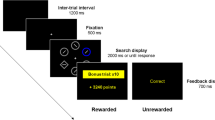

Humans appear to act in response to environmental demands or to pursue self-chosen goals. In the laboratory, these situations are often investigated with forced- and free-choice tasks: in forced-choice tasks, a stimulus determines the one correct response, while in free-choice tasks the participants choose between response alternatives. We compared these two tasks regarding their susceptibility to dual-task interference when the concurrent task was always forced-choice. If, as was suggested in the literature, both tasks require different “action control systems,” larger dual-task costs for free-choice tasks than for forced-choice tasks should emerge in our experiments, due to a time-costly switch between the systems. In addition, forced-choice tasks have been conceived as “prepared reflexes” for which all intentional processing is said to take place already prior to stimulus onset giving rise to automatic response initiation upon stimulus onset. We report three experiments with different implementations of the forced- vs. free-choice manipulation. In all experiments we replicated slower responses in the free- than in the forced-choice task and the typical dual-task costs. These latter costs, however, were equivalent for forced- and free-choice tasks. These results are easier to reconcile with the assumption of one unitary “action control system.”

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The term “action control systems” is still a bit vague. In our understanding, it refers to two largely different neural networks responsible for carrying out one action type or the other. When referring to this literature, we will, however, continue to use the term “system” although our data does not speak to the neural substrates.

We will discuss one special case of parallel processing in the “General Discussion”.

Another difference between the forced- and free-choice tasks used in Experiment 1 relates to the fact that the forced-choice task entailed a “consistent mapping” of stimuli and responses, while the free-choice task can be construed as entailing a “varied mapping”: to the same stimulus different responses are required. There is evidence for automatic retrieval of responses and/or tasks upon stimulus perception from the task-switching literature (e.g., Koch, Prinz, & Allport, 2005; Waszak, Hommel, & Allport, 2003), and thus the free-choice stimulus might re-activate the last response associatively and lead to increased response conflict. With the design we used in Experiment 2 and 3, this additional difference should be less pronounced.

If one views forced- vs. free-choice tasks as a continuum, this particular task might be a shift toward the forced-choice pole because it requires extracting the two possible stimuli and the respective responses. Still, however, it requires a “free-choice” between the two possible responses.

Against this background, it should be noted again that the simplified (and theoretical) distinction we have made here by contrasting stimulus- and goal-driven actions does not imply “real”, conceptual differences—the interpretation made here even argues against it. Rather, this terminology should only highlight the aspect that determines the accuracy or appropriateness of the emitted action. As both require at least an intention-in-action, the term “intention-based” to characterize only actions operationalized by free-choice tasks (Herwig et al., 2007; Keller et al., 2006; Waszak et al., 2005) is thus incomplete and potentially misleading.

References

Astor-Jack, T., & Haggard, P. (2004). Intention and reactivity. In G. W. Humphreys & J. M. Riddoch (Eds.), Attention in action: Advances from cognitive neuroscience (pp. 109–130). Hove: Psychology Press.

Baddeley, A. (2007). Working memory, thought, and action. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Berlyne, D. E. (1957a). Conflict and choice time. British Journal of Psychology, 48, 106–118.

Berlyne, D. E. (1957b). Uncertainty and conflict: A point of contact between information-theory and behavior-theory concepts. Psychological Review, 64, 329–339.

Botvinick, M. M., Braver, T. S., Barch, D. M., Carter, C. S., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychological Review, 108, 624–652.

Brass, M., & Haggard, P. (2008). The what, when, whether model of intentional action. The Neuroscientist, 14, 319–325.

Cunnington, R., Windischberger, C., Deecke, L., & Moser, E. (2003). The preparation and readiness for voluntary movement: A highfield event-related fMRI study of the Bereitschafts-BOLD response. Neuroimage, 20, 404–412.

Devaine, M., Waszak, F., & Mamassian, P. (2013). Dual process for intentional and reactive decisions. PLoS Computational Biology, 9, e1003013. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003013.

Elsner, B., & Hommel, B. (2001). Effect anticipation and action control. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 27, 229–240.

Fleming, S. M., Mars, R. B., Gladwin, T. E., & Haggard, P. (2009). When the brain changes its mind: Flexibility of action selection in instructed and free choices. Cerebral Cortex, 19, 2352–2360.

Frith, C. (2013). The psychology of volition. Experimental Brain Research, 229, 289–299.

Gaschler, R., & Nattkemper, D. (2012). Instructed task demands and utilization of action effect anticipation. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 578. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00578.

Goldberg, G. (1985). Supplementary motor area structure and function: Review and hypotheses. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 8, 567–588.

Gollwitzer, P. M. (1999). Implementation intentions. Strong effects of simple plans. American Psychologist, 54, 493–503.

Halvorson, K. M., Ebner, H., & Hazeltine, E. (2013). Investigating perfect timesharing: The relationship between IM-compatible tasks and dual-task performance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 39, 413–432.

Harleß, E. (1861). Der Apparat des Willens [The Apparatus of Will]. Zeitschrift für Philosophie und philosophische Kritik, 38, 50–73.

Hazeltine, E., Ruthruff, E., & Remington, R. W. (2006). The role of input and output modality pairings in dual-task performance: Evidence for content-dependent central interference. Cognitive Psychology, 52, 291–345.

Herbart, J. F. (1825). Psychologie als Wissenschaft neu gegründet auf Erfahrung, Metaphysik und Mathematik [Psychology as a science newly founded on experience, metaphysics, and mathematics]. Königsberg: August Wilhelm Unzer.

Herwig, A., Prinz, W., & Waszak, F. (2007). Two modes of sensorimotor integration in intention-based and stimulus-based actions. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 60, 1540–1554.

Herwig, A., & Waszak, F. (2009). Intention and attention in ideomotor learning. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 62, 219–227.

Herwig, A., & Waszak, F. (2012). Action-effect bindings and ideomotor learning in intention- and stimulus-based actions. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 444. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00444.

Hommel, B. (2000). The prepared reflex: Automaticity and control in stimulus-response translation. In S. Monsell & J. Driver (Eds.), Control of cognitive processes: attention and performance XVIII (pp. 247–273). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Hommel, B., Müsseler, J., Aschersleben, G., & Prinz, W. (2001). The theory of event coding (TEC): A framework for perception and action planning. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24, 849–937.

Hughes, G., Schütz-Bosbach, S., & Waszak, F. (2011). One action system or two? Evidence for common central preparatory mechanisms in voluntary and stimulus-driven actions. The Journal of Neuroscience, 31, 16692–16699.

Jahanshahi, M., Dirnberger, G., Fuller, R., & Frith, CD. (2000). The role of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in random number generation: A study with positron emission tomography. Neuroimage, 12, 713–725.

Jahanshahi, M., Jenkins, I. H., Brown, R. G., Marsden, C. D., Passingham, R. E., & Brooks, D. J. (1995). Self-initiated versus externally triggered movements. I. An investigation using measurement of regional cerebral blood flow with PET and movement-related potentials in normal and Parkinson’s disease subjects. Brain, 118, 913–933.

James, W. (1890/1981). The principles of psychology (vol. 2). Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Janczyk, M. (2013). Level 2 perspective taking entails two processes: Evidence from PRP experiments. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 39, 1878–1887.

Janczyk, M., Dambacher, M., Bieleke, M., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2014). The benefit of no choice: Goal-directed plans enhance perceptual processing. Psychological Research. doi:10.1007/s00426-014-0549-5.

Janczyk, M., Heinemann, A., & Pfister, R. (2012). Instant attraction: Immediate action-effect bindings occur for both, stimulus- and goal-driven actions. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 446. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00446.

Janczyk, M., & Kunde, W. (2014). The role of effect grouping in free-choice response selection. Acta Psychologica, 150, 49–54.

Janczyk, M., Pfister, R., Crognale, M. A., & Kunde, W. (2012). Effective rotations: Action effects determine the interplay of mental and manual rotations. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 141, 489–501.

Janczyk, M., Pfister, R., Hommel, B., & Kunde, W. (2014). Who is talking in backward crosstalk? Disentangling response- from goal-conflict in dual-task performance. Cognition, 132, 30–43.

Janczyk, M., Pfister, R., & Kunde, W. (2012). On the persistence of tool-based compatibility effects. Journal of Psychology, 220, 16–22.

Janczyk, M., Pfister, R., Wallmeier, G., & Kunde, W. (2014). Exceptions to the PRP effect? A comparison of prepared and unconditioned reflexes. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 40, 776–786.

Janczyk, M., Skirde, S., Weigelt, M., & Kunde, W. (2009). Visual and tactile action effects determine bimanual coordination performance. Human Movement Science, 28, 437–449.

Keller, P. E., Wascher, E., Prinz, W., Waszak, F., Koch, I., & Rosenbaum, D. A. (2006). Differences between intention-based and stimulus-based actions. Journal of Psychophysiology, 20, 9–20.

Kiesel, A., Steinhauser, M., Wendt, M., Falkenstein, M., Jost, K., Philipp, A. M., et al. (2010). Control and interference in task switching—A review. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 849–874.

Koch, I., Prinz, W., & Allport, A. (2005). Involuntary retrieval in alphabetic-arithmetic tasks: Task-mixing and task-switching costs. Psychological Research, 69, 252–261.

Krieghoff, V., Brass, M., Prinz, W., & Waszak, F. (2009). Dissociating what and when of intentional actions. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 3, 3. doi:10.3389/neuro.09.003.2009.

Kühn, S., Elsner, B., Prinz, W., & Brass, M. (2009). Busy doing nothing: Evidence for nonaction-effect binding. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 16, 542–549.

Kunde, W. (2001). Response-effect compatibility in manual choice reaction tasks. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 27, 387–394.

Kunde, W., Pfister, R., & Janczyk, M. (2012). The locus of tool-transformation costs. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 38, 703–714.

Logan, G. D., & Gordon, R. D. (2001). Executive control of visual attention in dual-task situations. Psychological Review, 108, 393–434.

Lotze, H. R. (1852). Medicinische Psychologie oder Physiologie der Seele [Medical psychology or the physiology of the mind]. Leipzig: Weidmann’sche Buchhandlung.

Masson, M. E. J. (2011). A tutorial on a practical Bayesian alternative to null-hypothesis testing. Behavior Research Methods, 43, 679–690.

Mattler, U., & Palmer, S. (2012). Time course of free-choice priming effects explained by a simple accumulator model. Cognition, 123, 347–360.

Metzker, M., & Dreisbach, G. (2009). Bidirectional priming processes in the Simon task. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 35, 1770–1783.

Miller, J., & Reynolds, A. (2003). The locus of redundant-targets and non-targets effects: Evidence from the psychological refractory period paradigm. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 29, 1126–1142.

Miller, J., Rolke, B., & Ulrich, R. (2009). On the optimality of serial and parallel processing in the psychological refractory period paradigm: Effects of the distribution of stimulus onset asynchronies. Cognitive Psychology, 58, 273–310.

Müller, V., Brass, M., Waszak, F., & Prinz, W. (2007). The role of the preSMA and the rostral cingulate zone in internally selected actions. Neuroimage, 37, 1354–1361.

Nachev, P., & Husain, M. (2010). Action and the fallacy of ‘internal’: Comment on Passingham et al. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 14, 192–193.

Nachev, P., Kennard, C., & Husain, M. (2008). Functional role of supplementary and pre-supplementary motor areas. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9, 856–869.

Oberauer, K., & Kliegl, R. (2006). A formal model of capacity limits in working memory. Journal of Memory and Language, 55, 601–626.

Obhi, S. S., & Haggard, P. (2004). Internally and externally triggered actions are physically distinct and independently controlled. Experimental Brain Research, 156, 518–523.

Pashler, H. (1994). Dual-task interference in simple tasks: Data and theory. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 220–244.

Passingham, R. E., Bengtsson, S. L., & Lau, H. C. (2010a). Medial frontal cortex: From self-generated action to reflection on one’s own performance. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 14, 16–21.

Passingham, R. E., Bengtsson, S. L., & Lau, H. C. (2010b). Is it fallacious to talk of self-generated action? Response to Nachev and Husain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 14, 193–194.

Pfister, R., & Janczyk, M. (2012). Harleß’ apparatus of will: 150 years later. Psychological Research, 76, 561–565.

Pfister, R., & Janczyk, M. (2013). Confidence intervals for two sample means: Calculation, interpretation, and a few simple rules. Advances in Cognitive Psychology, 9, 74–80.

Pfister, R., Kiesel, A., & Hoffmann, J. (2011). Learning at any rate: Action-effect learning for stimulus-based actions. Psychological Research, 75, 61–65.

Pfister, R., Kiesel, A., & Melcher, T. (2010). Adaptive control of ideomotor effect anticipations. Acta Psychologica, 135, 316–322.

Prinz, W. (1998). Die Reaktion als Willenshandlung [Responses considered as voluntary actions]. Psychologische Rundschau, 49, 10–20.

Raftery, A. E. (1995). Bayesian model selection in social research. In P. V. Marsden (Ed.), Sociological methodology (pp. 111–196). Cambridge: Blackwell.

Rowe, J. B., Hughes, L., & Nimmo-Smith, L. (2010). Action selection: A race model for selected and non-selected actions distinguishes the contribution of premotor and prefrontal areas. Neuroimage, 51, 888–896.

Schüür, F., & Haggard, P. (2011). What are self-generated actions? Consciousness and Cognition, 20, 1697–1704.

Schweickert, R. (1978). A critical path generalization of the additive factor method: Analysis of a stroop task. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 18, 105–139.

Searle, J. R. (1980). The intentionality of intention and action. Cognitive Science, 4, 47–70.

Searle, J. R. (1983). Intentionality. An essay in the philosophy of mind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sternberg, S. (1969). The discovery of processing stages: Extensions of Donders' method. Acta Psychologica, 30, 276–315.

Stock, A., & Stock, C. (2004). A short history of ideo-motor action. Psychological Research, 68, 176–188.

Verleger, R., Jaskowski, P., & Wascher, E. (2005). Evidence for an integrative role of P3b in linking reaction to perception. Journal of Psychophysiology, 19, 165–181.

Wagenmakers, E.-J. (2007). A practical solution to the pervasive problems of p values. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 14, 779–804.

Waszak, F., Hommel, B., & Allport, A. (2003). Task-switching and long-term priming: Role of episodic S-R-bindings in task-switch costs. Cognitive Psychology, 46, 361–413.

Waszak, F., Wascher, E., Keller, P., Koch, I., Aschersleben, G., Rosenbaum, D. A., et al. (2005). Intention-based and stimulus-based mechanisms in action selection. Experimental Brain Research, 162, 346–356.

Wiese, H., Stude, P., Nebel, K., de Greiff, A., Forsting, M., Diener, H. C., et al. (2004). Movement preparation in self-initiated versus externally triggered movements: An event-related fMRI-study. Neuroscience Letters, 371, 220–225.

Wolfensteller, U., & Ruge, H. (2011). On the timescale of stimulus-based action-effect learning. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 64, 1273–1289.

Woodworth, R. S. (1938). Experimental psychology. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Wilston.

Acknowledgment

This research was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; German Research Council), Project JA 2307/1-1, awarded to Markus Janczyk. We thank Iring Koch and an anonymous reviewer for valuable comments and suggestions on a previous version of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Janczyk, M., Nolden, S. & Jolicoeur, P. No differences in dual-task costs between forced- and free-choice tasks. Psychological Research 79, 463–477 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-014-0580-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-014-0580-6