Abstract

Background

Working in the operating room is characterized by high demands and overall workload of the surgical team. Surgeons often report that they feel more stressed when operating as a primary surgeon than in the function as an assistant which has been confirmed in recent studies. In this study, intra-individual workload was assessed in both intraoperative functions using a multidimensional approach that combined objective and subjective measures in a realistic work setting.

Methods

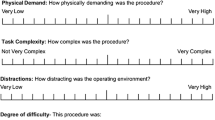

Surgeons’ intraoperative psychophysiologic workload was assessed through a mobile health system. 25 surgeons agreed to take part in the 24-hour monitoring by giving their written informed consent. The mobile health system contained a sensor electronic module integrated in a chest belt and measuring physiological parameters such as heart rate (HR), breathing rate (BR), and skin temperature. Subjective workload was assessed pre- and postoperatively using an electronic version of the NASA-TLX on a smartphone. The smartphone served as a communication unit and transferred objective and subjective measures to a communication server where data were stored and analyzed.

Results

Working as a primary surgeon did not result in higher workload. Neither NASA-TLX ratings nor physiological workload indicators were related to intraoperative function. In contrast, length of surgeries had a significant impact on intraoperative physical demands (p < 0.05; η 2 = 0.283), temporal demands (p < 0.05; η 2 = 0.260), effort (p < 0.05; η 2 = 0.287), and NASA-TLX sum score (p < 0.01; η 2 = 0.287).

Conclusions

Intra-individual workload differences do not relate to intraoperative role of surgeons when length of surgery is considered as covariate. An intelligent operating management that considers the length of surgeries by implementing short breaks could contribute to the optimization of intraoperative workload and the preservation of surgeons’ health, respectively. The value of mobile health systems for continuous psychophysiologic workload assessment was shown.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Schuld J, Bobkowski M, Shayesteh-Kheslat R, Kollmar O, Richter S, Schilling MK (2013) Ärztliche Ressourcennutzung in der Chirurgie auf dem Prüfstand—eine Worksampling-Analyse an einer deutschen Universitätsklinik. Zentralbl Chir 138:151–156

Ryu K, Myung R (2005) Evaluation of mental workload with a combined measure based on physiological indices during a dual task of tracking and mental arithmetic. Int J Ind Ergon 35:991–1009

DiDomenico A, Nussbaum MA (2008) Interactive effects of physical and mental workload on subjective workload assessment. Int J Ind Ergon 38:977–983

Wetzel CM, Kneebone RL, Woloshynowych M, Nestel D, Moorthy K, Kidd J, Darzi A (2006) The effects of stress on surgical performance. Am J Surg 191:5–10

Gaba DM, Howard SK (2002) Fatigue among clinicians and the safety of patients. N Engl J Med 347:1249–1255

Arora S, Hull L, Sevdalis N, Tierney T, Nestel D, Woloshynowych M, Darzi A, Kneebone R (2010) Factors compromising safety in surgery: stressful events in the operating room. Am J Surg 199:60–65

Carswell CM, Clarke D, Seales WB (2005) Assessing mental workload during laparoscopic surgery. Surg Innov 12:80–90

Howard SK, Gaba DM (2004) Trainee fatigue: are new limits on work hours enough? CMAJ 170:975–976

Zheng B, Cassera MA, Martinec DV, Spaun GO, Swanström LL (2010) Measuring mental workload during the performance of advanced laparoscopic tasks. Surg Endosc 24:45–50

Buddeberg-Fischer B, Klaghofer R, Stamm M, Siegrist J, Buddeberg C (2008) Work stress and reduced health in young physicians: prospective evidence from Swiss residents. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 82:31–38

Böhm B, Rötting N, Schwenk W, Grebe S, Mansmann U (2001) A prospective randomized trial on heart rate variability of the surgical team during laparoscopic and conventional sigmoid resection. Arch Surg 136:305–310

Belkic KL, Landsbergis PA, Schnall PL, Baker D (2004) Is job strain a major source of cardiovascular disease risk? Scand J Work Environ Health 30:85–128

Dine E, Fouquet A, Esquirol Y (2012) Cardiovascular diseases and psychosocial factors at work. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 105:33–39

Ellins E, Halcox J, Donald A, Field B, Brydon L, Deanfield J, Steptoe A (2008) Arterial stiffness and inflammatory response to psychophysiological stress. Brain Behav Immun 22:941–948

DiDomenico A, Nussbaum MA (2011) Effects of different physical workload parameters on mental workload and performance. Int J Ind Ergon 41:255–260

Rieger A, Neubert S, Behrendt S, Weippert M, Kreuzfeld S, Stoll R (2012) 24-Hour Ambulatory Monitoring of Complex Physiological Parameters with a Wireless Health System. Feasibility, user compliance and application. Proceedings of the 9th IEEE International Multiconference on Systems, Signals and Devices (SSD), Chemnitz, Germany

Reason J (1995) Understanding adverse events: human factors. Qual Health Care 4:80–89

Berland A, Natvig GK, Gundersen D (2008) Patient safety and job-related stress: a focus group study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 24:90–97

Johnstone PL (1999) Occupational stress in the operating theatre suite: should employers be concerned? Aust Health Rev 22:60–80

Kuhn EW, Choi YH, Schonherr M, Liakopoulos OJ, Rahmanian PB, Choi CY, Wittwer T, Wahlers T (2013) Intraoperative stress in cardiac surgery: attendings versus residents. J Surg Res 182:e43–e49

Kurmann A, Tschan F, Semmer NK, Seelandt J, Candinas D, Beldi G (2012) Human factors in the operating room—the surgeon’s view. Trends Anaesth Crit Care 2:224–227

Lingard L, Garwood S, Poenaru D (2004) Tensions influencing operating room team function: does institutional context make a difference? Med Educ 38:691–699

Becker WGE, Ellis H, Goldsmith R, Kaye AM (1983) Heart rates of surgeons in theatre. Ergonomics 26:803–807

Neubert S, Arndt D, Thurow K, Stoll R (2010) Mobile real-time data acquisition system for application in preventive medicine. Telemed J E Health 16:504–509

Neubert S, Behrendt S, Rieger A, Weippert M, Kumar M, Stoll R (2011) Echtzeit-Telemonitoring-System in der Präventivmedizin. In: Duesburg F (ed) E-Health 2012 – Informationstechnologien und Telematik im Gesundheitswesen. Medical Future Verlag, Solingen, pp 249–252

Hart SG, Staveland LE (1988) Development of NASA-TLX (Task Load Index): results of empirical and theoretical research. Adv Psychol 52:139–183

Hart SG (2006) NASA-task load index (NASA-TLX); 20 years later. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, HFES 2006, San Francisco, CA, pp 904–908

Szalma JL, Warm JS, Matthews G, Dember WN, Weiler EM, Meier A, Eggemeier FT (2004) Effects of sensory modality and task duration on performance, workload, and stress in sustained attention. Hum Factors 46:219–233

O’Donnell RD, Eggemeier FT (1986) Workload assessment methodology. In: Boff K, Kaufman L, Thomas J (eds) Handbook of perception and human performance, vol II., Cognitive Processes and PerformanceWiley Interscience, New York, pp 42.41–42.49

Arora S, Sevdalis N, Nestel D, Woloshynowych M, Darzi A, Kneebone R (2010) The impact of stress on surgical performance: a systematic review of the literature. Surgery 147:318–330

Lockley SW, Cronin JW, Evans EE, Cade BE, Lee CJ, Landrigan CP, Rothschild JM, Katz JT, Lilly CM, Stone PH, Aeschbach D, Czeisler CA (2004) Effect of reducing interns’ weekly work hours on sleep and attentional failures. N Engl J Med 351:1829–1837

Samkoff JS, Jacques CH (1991) A review of studies concerning effects of sleep deprivation and fatigue on residents’ performance. Acad Med 66:687–693

Von dem Knesebeck O, Klein J, Grosse Frie K, Blum K, Siegrist J (2010) Psychosoziale Arbeitsbelastungen bei chirurgisch tätigen Krankenhausärzten. Dtsch Ärztebl 104:248–253

Buddeberg-Fischer B, Klaghofer R, Buddeberg C (2005) Arbeitsstress und gesundheitliches Wohlbefinden junger Ärztinnen und Ärzte. Z psychosom Med Psychother 51:163–178

Klein MI, Warm JS, Riley MA, Matthews G, Gaitonde K, Donovan JF (2008) Perceptual distortions produce multidimensional stress profiles in novice users of an endoscopic surgery simulator. Hum Factors 50:291–300

Czyzewska E, Kiczka K, Czarnecki A, Pokinko P (1983) The surgeon’s mental load during decision making at various stages of operations. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 51:441–446

Song MH, Tokuda Y, Nakayama T, Sato M, Hattori K (2009) Intraoperative heart rate variability of a cardiac surgeon himself in coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. Interactive Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 8:639–641

Klein M, Andersen LPH, Alamili M, Gögenur I, Rosenberg J (2010) Psychological and physical stress in surgeons operating in a standard or modern operating room. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 20:237–242

Malhotra N, Poolton JM, Wilson MR, Ngo K, Masters RSW (2012) Conscious monitoring and control (reinvestment) in surgical performance under pressure. Surg Endosc. doi:10.1007/s00464-012-2193-8

Zheng B, Jiang X, Tien G, Meneghetti A, Panton ONM, Atkins MS (2012) Workload assessment of surgeons: Correlation between NASA TLX and blinks. Surg Endosc 26:2746–2750

Fahrenberg J, Myrtek M (1996) Ambulatory assessment: computer-assisted psychological and psychophysiological methods in monitoring and field studies. Hogrefe & Huber, Seattle

Haga S, Shinoda H, Kokubun M (2002) Effects of task difficulty and time-on-task on mental workload. Jpn Psychol Res 44:134–143

Swangnetr M, Kaber D, Vorberg E, Fleischer H, Thurow K (2014) Identifying automation opportunities in life science processes through operator task modeling and workload assessment. In: Ahram T, Karwowski W, Marek T (eds) 5th International Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics AHFE 2014, Krakow, Poland, pp 6248–6255

Engelmann C, Schneider M, Kirschbaum C, Grote G, Dingemann J, Schoof S, Ure BM (2011) Effects of intraoperative breaks on mental and somatic operator fatigue: a randomized clinical trial. Surg Endosc 25:1245–1250

Engelmann C, Schneider M, Grote G, Kirschbaum C, Dingemann J, Osthaus A, Ure B (2012) Work breaks during minimally invasive surgery in children: patient benefits and surgeon’s perceptions. Eur J Pediatr Surg 22:439–444

Fahrenberg J, Myrtek M (2001) Progress in ambulatory assessment : computer-assisted psychological and psychophysiological methods in monitoring and field studies. Hogrefe & Huber, Seattle

Fahrenberg J, Myrtek M, Pawlik K, Perrez M (2007) Ambulatory assessment—capturing behavior in daily life. A behavioral science approach to psychology. Psychol Rundsch 58:12–23

Myrtek M (2004) Heart and emotion: ambulatory monitoring studies in everyday life. Hogrefe & Huber, Cambridge, MA

Rau R, Richter P (1996) Psychophysiological analysis of strain in real life work situations. In: Fahrenberg J, Myrtek M (eds) Ambulatory assessment: computer-assisted psychological and psychophysiological methods in monitoring and field studies. Hogrefe & Huber, Kirkland, USA, pp 271–285

Wilson MR, Poolton JM, Malhotra N, Ngo K, Bright E, Masters RS (2011) Development and validation of a surgical workload measure: the surgery task load index (SURG-TLX). World J Surg 35:1961–1969

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to the reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions. This study was realized as part of the project eHealth MV, funded by the State of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania in Germany as well as by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) in the program “Center for Innovation Competence (ZIK)”.

Disclosures

Drs. Rieger, Fenger, Neubert, Weippert, Kreuzfeld, and Prof. Stoll have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Annika Rieger and Sebastian Fenger are co-first authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rieger, A., Fenger, S., Neubert, S. et al. Psychophysical workload in the operating room: primary surgeon versus assistant. Surg Endosc 29, 1990–1998 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3899-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3899-6