Abstract

When long time series are analyzed, two nearby periods may show significantly different trends, which is known as trend turning. Trend turning is common in climate time series and crucial when climate change is investigated. However, the available detection methods for climate trend turnings are relatively few, especially for the methods which have the ability of detecting multiple trend turnings. In this article, we propose a new methodology named as the running slope difference (RSD) t test to detect multiple trend turnings. This method employs a t-distributed statistic of slope difference to test the sub-series trend difference of the time series, thereby identifying the turning points. We compare the RSD t test method with some other existing trend turning detection methods in an idealized time series case and several climate time series cases. The results indicate that the RSD t test method is an effective tool for detecting climate trend turnings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Global mean surface air temperature (GMT) rose roughly 0.85 °C from 1880 to 2012 (IPCC 2013), attributing mainly to an increase in atmospheric greenhouse gases (GHGs). The earth’s climate is a multiple-factor complex system; although GHGs have been monotonically increasing, GMT may result in little or no warming over some decadal timescale periods (Chen et al. 2015; Li et al. 2013, 2018; England et al. 2014; Trenberth and Fasullo 2013). Temperature change from warming to little or no warming (or vice versa) is a typical example of climate trend turning (also known as trend change or structural change of the trend). Trend turning is a commonly observed phenomenon in many climate parameters, such as precipitation (Alexander et al. 2006; Groisman and Easterling 1994), tropical cyclone frequency (Cheung et al. 2015), haze days (Zhao et al. 2016), and the index of some climate patterns like NAO (Hurrell 1995; Li and Wang 2003). Understanding trend turning is important because it can influence the interpretation of climate variation as well as guiding future research directions.

Periods of time exhibiting GHGs increases without simultaneous GMT warming are known as warming hiatus (or warming slowdown). From the 1940s to the early 1970s, there was a three-decade-long hiatus period (England et al. 2014; Karl et al. 2000; Li et al. 2013; Xing et al. 2017) with the CO2 concentration rapidly increasing since the 1950s (IPCC 2013). And recently, a relatively slow rate of GMT warming since the early 2000s to 2014 was considered as another hiatus event by many climate scientists (Chen and Luo 2017; Easterling and Wehner 2009; England et al. 2014; Feng et al. 2017; Huang et al. 2017; Kosaka and Xie 2013; Li et al. 2013; Trenberth and Fasullo 2013; Yu and Lin 2018; Yu et al. 2017; Li et al. 2018). A recent work by Meehl et al. (2014) shows that only a few of IPCC climate models correctly projected the global warming slowdown in the early 2000s (10 out of 262 uninitialized CMIP5 simulations actually projected the observed warming trend), and this result indicates that we are still lacking knowledge about decadal timescale variability of global warming and more efforts should be made to improve future climate projection.

In the previous study, significant research attention has been focused on long-term linear trends of climate. Many well-known trend test methodologies such as Student’s t test, Mann-Kendall trend test (Mann 1945; Kendall 1975), Theil-Sen slope estimator (Theil 1950; Sen 1968), and innovative trend analysis (Şen 2012) have been widely used in climate research. However, the available detection methods for climate trend turning are relatively few. And many of these available methods are restricted to only a single turning point (Chu and White 1992; Andrews 1993; Ploberger and Kramer 1996; Perron and Zhu 2005; Toms and Lesperance 2003).

Previous studies have pointed out that the ability of detecting multiple changes is important for climate detection methods (Jiang et al. 2002; Xiao and Li 2007). Currently, there are mainly two types of methods for detecting multiple trend turnings. One is the optimal piecewise linear regression (OPLR; Liu et al. 2010; Tomé and Miranda 2004; Yao et al. 2017), and the other one is running trend test (Maher et al. 2014; Meehl et al. 2011; Thanasis et al. 2011). However, both existing methods usually fail to stress the statistical significance test of the sub-series trend difference during their detections. The OPLR method finds a piecewise regression solution which minimizes the residual sum under the condition that two nearby sub-series trends must have opposite sign (Tomé and Miranda 2004). But opposite sign of two trends cannot be equal to significant difference of two trends. Using opposite sign as the condition for identifying the turning points (also mentioned as trend breakpoints or trend change points) will reject trend turnings in which both sub-series have the same sign, and may increase the risk of false alarm. The running trend test methods detect trend turnings making use of existing trend slope significant test on running windows along the time series (Thanasis et al. 2011). Like the OPLR method, this method may reject trend turnings in which both sub-series have the same sign as well.

Based on the above facts, we have studied the characteristics of climate trend turning. The most basic characteristic of trend turning is the sub-series trends difference between both sides of the turning-point, so we propose a new trend turning detection methodology by testing the sub-series trend difference. This new method uses a statistical t test of slope differences to identify the turning points and we name it as running slope difference (RSD) t test. The RSD t test has the capacity to detect multiple times of trend turnings and provides a test of significance for these trend turnings.

The remainder of this article is as follows. In Section 2, we discuss some major characteristics of the trend turning. The RSD t test detection method is given in Section 3. And next in Section 4, we compare the RSD t test method with some existing methods in an idealized time series case and several climate time series cases. At last, in Section 5, we draw our conclusions.

2 Characteristics of trend turning

Turning type is a major characteristic of trend turning. According to the different combination of trends that occur before and after turning, trend turning can be divided into three types: TR (trend reversal), TN (trend vs. no trend), and TD (trends are different only in degree, and are in same sign). All of trend turning types and their sub-types are listed in Table 1. TR represents trend reversal between statistically significant positive and negative trends; therefore, it includes two sub-types. TN represents trend turning from no trend to significant trend (or vice versa); it includes four sub-types. TD represents trend turning between two same-sign trends (either significant positive or negative); it includes four sub-types. Existing detection methods usually ignored the TD type of trend turning. However, the TD type of trend turning is also important in climate research and we will further discuss it in Section 4.

Analyzing all turning types, the common characteristic of trend turnings is the sub-series trend difference between both sides of the turning point. With a previous trend transition into a different trend after the turning point, the slopes before and after turning will exhibit large differences. Therefore, the statistical significance of sub-series slope difference can be used as an indicator of trend turning. The RSD t test is designed based on this fact, and it has the ability of detecting all three types of trend turnings.

For trend turning detection, the main scientific problem is to identify the turning points of the sample time series. When turning points are determined, the original time series can be subdivided into several trend phases (linear segments). Then, the existing trend significant test can be used to further analyze the trend of each phase. In this study, we focus on identification of the turning points and three basic features of each trend phase: (1) the duration of each phase, (2) the least square trend value of each phase, and (3) the least square regression of each phase.

3 The running slope difference t test detection method

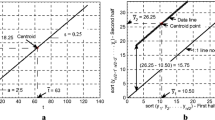

3.1 Statistical test of slope difference

The statistical test of slope difference is performed with a t-distribution statistic. Let Y : {yi = βYi + αY + εi| 1 ≤ i ≤ n} and Z : {zj = βZj + αZ + εj| 1 ≤ j ≤ m} be the two sample series; the length of Y is n and Z is m. βY and βZ are the slopes of sample series Y and Z, αY and αZ are the intercepts, and εi and εj are the error terms. The null hypothesis here is βY = βZ. Assume that εi and εj are normally distributed independent random variables with zero mean and variance σ2. Let \( \tilde{Y}:\left\{{\tilde{y}}_i|1\le i\le n\right\} \) and \( \tilde{Z}:\left\{{\tilde{z}}_j|1\le j\le m\right\} \) be the least-squares linear regressions of Y and Z and \( {\tilde{\beta}}_Y \) and \( {\tilde{\beta}}_Z \) are the least-squares estimators of slopes βY and βZ. The general form of the slope difference t-distribution statistic (tslope) between Y and Z is:

where

is the variance of the regression errors and \( C=\frac{NM}{N+M} \), \( N=\sum \limits_{i=1}^n{\left(i-\frac{n+1}{2}\right)}^2 \), and \( M=\sum \limits_{j=1}^m{\left(j-\frac{m+1}{2}\right)}^2 \) are known constants.

Since εi and εj are assumed to be normally distributed independent random variables with zero mean, the distribution of both regression errors (residuals \( {y}_i-{\tilde{y}}_i \) and \( {z}_j-{\tilde{z}}_j \)) follows the normal distribution and both are independent for each other; then, the sampling distribution of \( {X}_Y=\frac{1}{\sigma^2}\sum \limits_{i=1}^n{\left({y}_i-{\tilde{y}}_i\right)}^2\sim {\chi}^2\left(n-2\right) \) and \( {X}_Z=\frac{1}{\sigma^2}\sum \limits_{j=1}^m{\left({z}_j-{\tilde{z}}_j\right)}^2\sim {\chi}^2\left(m-2\right) \) is χ2 distribution (see, e.g., von Storch and Zwiers 1999). As the least-squares estimators are unbiased, the expectation and variance of the slope difference βY − βZ are \( E\left({\beta}_Y-{\beta}_Z\right)={\tilde{\beta}}_Y-{\tilde{\beta}}_Z \) and \( \mathrm{Var}\left({\beta}_Y-{\beta}_Z\right)=\frac{1}{C}{\sigma}^2 \), respectively; thereby, \( Z=\sqrt{C}\frac{\left({\beta}_Y-{\beta}_Z\right)-\left({\tilde{\beta}}_Y-{\tilde{\beta}}_Z\right)}{\sigma}\sim N\left(0,1\right) \) is normally distributed (see, e.g., von Storch and Zwiers 1999). From XY, XZ, and Z, it can be inferred that \( {t}_{\mathrm{slope}}=\frac{Z}{\sqrt{\left({X}_Y+{X}_Z\right)/n+m-4}}\sim t\left(n+m-4\right) \) is the t-distribution and the degrees of freedom are f = n + m − 4. The null hypothesis of no slope difference between Y and Z is rejected at the significance level α if ∣tslope ∣ ≥ tn + m − 4, 1 − α/2.

For climate time series, the regression errors here may not be independent of each other; this means degrees of freedom estimated by the above formula (n + m − 4) may more than the effective ones (Santer et al. 2000; Xiao and Li 2007). In practice, the degrees of freedom above are replaced by the effective degrees of freedom Neff in consideration of the autocorrelation effect (Bretherton et al. 1999; Ebisuzaki 1997; Santer et al. 2000). Neff is evaluated following the work of Bartlett (1946) as:

where ρj is the autocorrelation coefficient with a lagged scale j and N = n + m.

3.2 Detection process

Climate variability is frequently characterized by the multi-timescales (Ji et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2009). And trend turning of a sample time series usually for different timescales may also be different (Fig. 2, in Tomé and Miranda 2004). Therefore, users of the RSD t test method should determine the trend turning timescale T according to their specific study issue before the trend turning detection. The parameter T is the basic timescale which is used to analyze the trend of sub-series. After the parameter T is determined, only the sub-series greater than or equal to timescale T can be detected (the same as in the parameter T in the OPLR method by Tomé and Miranda 2004).

To locate the turning points using tslope, the RSD t test adopts a running test technique which first finds all the potential turning points of possible trend turnings (candidates of the turning points). Let L : {li| 1 ≤ i ≤ k} be the sample time series. Set τ to be the running window, parameter τ is determined based on the timescale T. We suggest that the value of τ should be a little smaller than T considering that some time series may have a length T trend phase (usually we set τ = T − 1 or τ = T − 2, and τ should not be less than 3/4T). For each point la(a ∈ [τ + 1, k − τ]), the difference between the slope of sub-time series La1 : {li| a − τ ≤ i ≤ a − 1} and the slope of sub-time series La2 : {li| a + 1 ≤ i ≤ a + τ} is tested using tslope. If the slope of La1 is significantly different from the slope of La2, it means that a potential turning may occur at point la. All the points which have passed the running slope difference test will form several continuous intervals, with each interval corresponding to a possible trend turning. The RSD t test picks the point which has the maximum absolute slope difference value in each interval as the potential turning point.

Not all these potential turning points are true turning points, some of which might be false turnings caused by the running test. Thus, a check process is designed to eliminate these false turnings in the RSD t test. Assume that we got k potential turning points, they subdivided the sample time series L into k + 1 trend phases. For each potential turning point, the two nearby trend phases pair will be checked again using tslope to ensure that they exhibit significant trend differences. Usually, the length of each trend phase is longer than the running window τ; thereby, some potential turning points may not pass the test in the check process since the test samples have changed (the two nearby trend phases pair usually contains more points than La1 and La2). Potential turning points which fail to pass the check are the false turnings. Removing all the false turnings, the rest points are turning points of sample time series L.

In this article, we will compare the trend turning detection results of the RSD t test with two existing methods which are commonly used for detecting climate trend turnings. One method is the optimal piecewise linear regression (OPLR) method from Tomé and Miranda (2004), and the other one is a running trend test (R-MK) based on the MK trend test (Mann 1945; Kendall 1975). The statistic of MK trend test used here is a modified version from Yue and Wang (2004), which can be applied in both independent and autocorrelated data.

4 Application

4.1 Idealized time series case

To further illustrate the performance of the RSD t test method and compare it with existing methods, we built an idealized sample case of three time series. The first time series I1 (Fig. 1a, thick line) is a series with six times of different type trend turnings, the length of each trend phase being 60–90 points. The information of turning points of I1 is listed in Table 2 (trend turning true value, rows 2–4). The second time series I2 (Fig. 1d, thick line) is a series with no trend turning but has the same overall slope value as I1. The third time series I3 (Fig. 1g, thick line) is a series with no trend turning and zero overall slope value. We superpose these series with randomly generated noise and detect their trend turnings using the RSD t test method, as well as the OPLR and R-MK methods.

Trend turning detection of idealized time series with independent noise using running slope difference (RSD) t test method (detection parameter T = 50, τ = T − 2, confidence level at 99%). a Idealized time series I1 (thick line) along with independent noise (thin line). b The detection process (running test and check) of series I1 with independent noise. Curve denotes the difference between slope of La1 and slope of La2 for each point la, and colored parts (black dash part) of this curve represent the points which have (have not) passed the significance test. Circles are the identified potential turning points. Bars denote the difference between slopes of two phases subdivided by each potential turning point. Colored solid circles and colored bars (black hollow circles and black bars) are the identified turning points (false turnings). c The trend turning estimations (colored thick line) of idealized time series I1 with independent noise (thin line). Dash vertical lines denote the turning points (specific values in Table 2). d, e, and f and g, h, and i The same as in a, b, and c, but for idealized time series I2 and I3 with independent noise

In the idealized case, we blended two types of randomly generated noise: the independent noise and the autocorrelated noise. The independent noise εt is a random, independent, and normally distributed series with zero mean (the standard deviation of the noise is set as 15). The autocorrelated noise xt is generated by a first-order autocorrelation process (AR (1); Box et al. 1976)

where εt is the independent noise, Φ is the lag-one autocorrelation coefficient. For the autocorrelated noise xt, the autocorrelation coefficient is set as Φ = 0.6. According to the work of Bartlett (1935), statistical tests which are based on hypothesis of independent sample and have no consideration of autocorrelation will have a very low accuracy when the autocorrelation coefficient come to 0.6 or more.

To compare the results of different trend turning detection methods, the timescale T of three methods are all set as 50 points. Other detection parameters for each method are as follows: for the RSD t test method, running window is set as τ = T − 2 and statistical test confidence level is set at 99%; for the OPLR method, the maximum number of trend turnings is set as 8; for the R-MK method, the threshold of significant trend is set at 95%.

Figure 1 is the trend turning detection of idealized time series with independent noise using the RSD t test method. For series I1, six times of different types of trend turnings have all been identified (Fig. 1c and the 6th row in Table 2). All the turning points correspond to the local maximum or minimum of the slope difference curve (Fig. 1b). These detection results are also stable and insensitive to the small changes of detection parameters T and τ. Table 3 shows a comparative experiment which uses different pairs of parameters T and τ (with only a small difference), all the detections having resulted similar results. For series I2 and I3, detection results show there is no trend turning just as we have designed (Fig. 1f, i). Although the running test process may bring several false turnings (Fig. 1e, h), these false turnings can be removed through the elimination process of false trend turning. Therefore, the final results of the RSD t test method are correct, with no false turnings.

Figure 2 is the trend turning detection results of idealized time series with independent noise using the OPLR method. As shown in Fig. 2a and the 7th row in Table 2, the OPLR method has the ability of identifying both the TR and TN types of trend turnings; however, it can hardly identify the TD type of trend turnings, missing all two TD-type turning points at 300 and 440 in I1. Furthermore, this method has a relatively high chance of triggering false alarm when the slope of sample time series is near 0 (Fig. 2a and c, one false alarm at point 187 in I1 and six false alarms in I3). These estimation errors mainly resulted from the lack of the statistical test of the sub-series trend difference. Figure 3 is the trend turning detection results of idealized time series with independent noise using the R-MK method. Like the OPLR method, the R-MK method also has the ability of identifying both the TR and TN types of trend turnings; however, it can hardly identify all the TD type of trend turnings as well (Fig. 3b and the 8th row in Table 2, R-MK has missed all two TD-type turning points at 300 and 440 in I1).

Trend turning detection of idealized time series with independent noise using optimal piecewise linear regression (OPLR) method (detection parameter T = 50). a The trend turning estimations (colored thick line) of idealized time series I1 with independent noise (thin line). Dash vertical lines denote the turning points (specific values in Table 2). b and c The same as in a, but for idealized time series I2 and I3 with independent noise

Trend turning detection of idealized time series with independent noise using running MK trend test (R-MK) method (detection parameter T = 50, confidence level at 95%). a The running MK test statistic Z (black curve) of series I1 with independent noise. Colored horizontal lines denote the confidence level threshold. b The trend turning estimations of idealized time series I1 with independent noise (thin line). Dash vertical lines denote the turning points (specific values in Table 2). c, d and e, f The same as in a, b, but for idealized time series I2 and I3 with independent noise

Assumption of independent observations could result in erroneous conclusions when the sample time series are autocorrelated. The statistic test of tslope used in the RSD t test method and the statistic trend test of MK used in the R-MK method both have such assumption. In the RSD t test method, the effect of autocorrelation is considered by using the effective degrees of freedom. And in the R-MK method, the statistic of the MK trend test is replaced by a modified version (the rationale of this modified version is also using the effective sample size) from Yue and Wang (2004). Figures 4, 5, and 6 are the trend turning detection results of idealized time series with autocorrelated noise using the RSD t test, OPLR, and R-MK methods. The detection results show that all three methods can be used to identify the trend turnings of the autocorrelated noise case as in the independent noise case, and the results between two cases are quite similar (rows 11–13 in Table 2). The RSD t test method has the ability of identifying all three types of trend turnings (Fig. 4c and Table 2), while the OPLR and R-MK methods can hardly identify all the TD type of trend turnings as in the independent noise case (the OPLR method has missed two TD-type turning points at 300 and 440 in I1, the R-MK method having missed one at 300). The OPLR method still has a relatively high chance of triggering false alarm when the slope of sample time series is near 0 in the autocorrelated noise case (Fig. 5a and c, one false alarm at point 190 in I1 and six false alarms in I3).

The same as in Fig. 1, but for trend turning detection of idealized time series with autocorrelated noise

The same as in Fig. 2, but for trend turning detection of idealized time series with autocorrelated noise

The same as in Fig. 3, but for trend turning detection of idealized time series with autocorrelated noise

4.2 Changes in the growth rate of global atmospheric CO2

In this section, we are testing the multidecadal trend turning of global atmospheric CO2 concentration about half a century. The atmospheric concentration of CO2 has increased since 1750 due to human activities and exceeded the pre-industrial levels by about 40% (IPCC 2013). Emissions of CO2 alone have caused a radiative forcing of 1.68 W m−2, which has a very high level of confidence to be the primary driver of global warming (IPCC 2013). Figure 7a shows the global atmospheric CO2 concentration from 1750 to 2005; this data is obtained from the work of Meinshausen et al. (2011). CO2 concentration has been monotonically increasing, with an obviously increasing growth rate.

Trend turning detection of the global CO2 concentration time series using RSD t test method (detection parameter T = 50 years, τ = T − 2, confidence level at 99%). a CO2 concentration time series. b The same as in Fig. 1b, but for the detection process of CO2 concentration time series. c The trend turning estimations (colored thick line) of CO2 concentration time series (thin line). Dash vertical lines denote the turning points (1840 and 1954). “Tr” and “D” represent the least square trend value and duration of each trend phase, respectively. Note that the least square trend value unit here is 102 ppm per decade and the duration unit is year

To detect the multidecadal trend turning of CO2 concentration using the RSD t test, OPLR, and R-MK methods, the timescale T is set as 50 years. Other detection parameters are set the same as in the idealized time series case.

Figure 7 is the trend turning detection results of CO2 concentration using the RSD t test method. Two TD-type trend turnings are identified respectively around the years of 1840 and 1954. These turning points divide the original time series into three phases: 1750–1839, 1841–1953, and 1955–2005. The growth rates of CO2 in the latter two phases are 4.5 and 24.6 times greater than that in the first phase, respectively. We note that the two turning points around the years of 1840 and 1954 correspond to the initial stages of the second industrial revolution and information revolution, and these results may suggest that technological advancements contribute strongly to anthropogenic CO2 emissions.

Figure 8 is the trend turning detection results of CO2 concentration using the OPLR method. The OPLR method also finds two turning points (around the years of 1843 and 1894); however, the regression error of the OPLR method is obviously greater than that of the RSD t test method (standard deviation of regression error is 8.0:1.4). Furthermore, the estimated trend value (− 0.01 × 102 ppm per decade) of the second phase (1844–1894) using the OPLR method has an opposite sign compared with its least square slope (2.72 × 102 ppm per decade) or Theil-Sen slope (2.72 × 102 ppm per decade). Figure 9 is the trend turning detection results of CO2 concentration using the R-MK method. The R-MK method shows that there are no trend turnings in CO2 concentration time series.

Trend turning detection of the global CO2 concentration time series using OPLR method (detection parameter T = 50). The trend turning estimations (colored thick line) of CO2 concentration time series (thin line). Dash vertical lines denote the turning points (1843 and 1894). “Tr” and “D” the same as in Fig. 7

Trend turning detection of the global CO2 concentration time series using R-MK method (detection parameter T = 50, confidence level at 95%). a The running MK test statistic Z (black curve) of CO2 concentration time series. Colored horizontal lines denote the confidence level threshold. b The trend turning estimations of CO2 concentration time series (thin line). Dash vertical lines denote the turning points (no trend turning)

Comparing these results of different detection methods, the RSD t test method is much more appropriate for identifying TD types of trend turnings. TD type of trend turning is common in the anthropogenic factors of climate such as atmospheric CO2 concentration; therefore, analysis using the RSD t test method may contribute to the understanding of how these factors changed in different time periods.

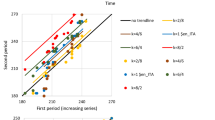

4.3 Trend turning in global temperature

In this section, we will use the RSD t test method to detect the decadal trend turnings of GMT time series. Three datasets which are common for studying global warming are used to detect the decadal trend turnings of GMT time series. These three datasets are HadCRUT4 dataset (Fig. 10a; Morice et al. 2012) which is developed by the Climatic Research Unit (University of East Anglia) in conjunction with the Hadley Centre (UK Met Office), GISTEMP dataset (Fig. 10d; Hansen et al. 2010) which is developed by the Goddard Institute for Space Studies (NASA), and NOAAGlobalTemp (NOAA-GT, used to known as MLOST) dataset (Fig. 10g; Smith et al. 2008; Vose et al. 2012) which is developed by the National Climatic Data Center (NOAA).

Trend turning detection of the global mean temperature (GMT) time series using RSD t test method (detection parameter T = 15 years, τ = T − 1, confidence level at 95%). a GMT time series from HadCRUT4 dataset. b The same as in Fig. 1b, but for the detection process of GMT time series from HadCRUT4 dataset. c The trend turning estimations (colored thick line) of GMT time series (thin line) from HadCRUT4 dataset. Dash vertical lines denote the turning points (1910, 1942, 1973, and 1999). “Tr” and “D” the same as in Fig. 7, but the least square trend value unit here is °C per decade. d, e, and f and g, h, and i The same as in a, b, and c, but for GISTEMP and NOAA-GT datasets (both turning points at 1910, 1942, and 1973)

To detect the decadal trend turning of GMT using the RSD t test, OPLR, and R-MK methods, the timescale T is set as 15 years following the work of Karl et al. (2000). The test sample size in this case is much smaller than that in the idealized time series case; thereby, the running window for the RSD t test method is set as τ = T − 1 and statistical test confidence level is set at 95%. Other detection parameters are set the same as in the idealized time series case.

Figures. 10, 11, and 12 are the trend turning detection results of GMT time series using the RSD t test, OPLR, and R-MK methods. The detection results of different methods and datasets during the period of 1880–1998 are generally consistent with each other, that is, all the results show that there are three times of trend turnings around the years of 1910, 1940, and 1970 during this period. In phases 1910–1940 and 1970–1998, GMT increases rapidly with trend values about 0.10~0.13 and 0.17~0.18 °C per decade, respectively. But in phases 1880–1910 and 1940–1970, although during these periods the CO2 concentration is still growing (Fig. 7), GMT trend shows a cooling or a warming hiatus about − 0.06~− 0.05 and − 0.03~− 0.02 °C per decade, respectively. These results are consistent with the IPCC assessment report (2013) and many other previous researches based on both eye inspect and statistical detection (Easterling and Wehner 2009; England et al. 2014; Karl et al. 2000; Li et al. 2013; Rahmstorf et al. 2017; Trenberth and Fasullo 2013).

Trend turning detection of the GMT time series using OPLR method (detection parameter T = 15). a The trend turning estimations (colored thick line) of GMT time series (thin line) from HadCRUT4 dataset. Dash vertical lines denote the turning points (1910, 1942, and 1973). “Tr” and “D” the same as in Fig. 7, but the least square trend value unit here is °C per decade. b and c The same as in a, but for GISTEMP and NOAA-GT datasets (turning points in 1911, 1942, and 1967 for GISTEMP dataset and in 1909, 1942, and 1968 for NOAA-GT dataset)

Trend turning detection of the GMT time series using R-MK method (detection parameter T = 15, confidence level at 95%). a The running MK test statistic Z (black curve) of GMT time series from HadCRUT4 dataset. Colored horizontal lines denote the confidence level threshold. b The trend turning estimations of GMT time series (thin line) from HadCRUT4 dataset. Dash vertical lines denote the turning points (1913, 1940, and 1976). c, d and e, f The same as in a, b, but for GISTEMP and NOAA-GT datasets (turning points in 1914, 1940, and 1980 for GISTEMP dataset and in 1910, 1940, and 1973 for NOAA-GT dataset)

For the first 15 years of the twenty-first century, despite the fact that GMT warming during 2000–2014 is indeed lower than that during 1970–1998, this change significant enough to be considered as the “global warming hiatus/slowdown” is still under controversy. The detection results of different methods and datasets are inconsistent during this period. Detection results of the RSD t test method show that in HadCRUT4 dataset, there is a significant trend turning around the year of 1998 known as TD type, and phase 2000–2014 has a lower but still warming trend compared with phase 1970–1998. In GISTEMP and NOAA-GT datasets, there is no significant trend turning around the year of 1998, but they still have a weak negative trend changing signal (Fig. 10e, h). In the detection results of the R-MK method, there are also signals of negative trend change in the running MK statistic around the year of 1998 (Fig. 12a, c, e).

The insignificant negative trend change of GMT around the year of 1998 may arise from the spatial difference of climate change. In some regions, there is no warming hiatus/slowdown around the year of 1998. For example, in the European region (40–60° N, 0–40° E), warming rates for 1970–1998 and 2000–2014 periods are about 0.16~0.22 and 0.22~0.27 °C per decade, respectively. But in other regions, there is robust warming hiatus/slowdown or even cooling signals around the year of 1998. For example, in the southeast tropical Pacific region (10–30° S, 100–150° W), warming rates for 1970–1998 and 2000–2014 periods are about 0.20~0.21 and − 0.26~− 0.18 °C per decade, respectively. To further understand the climate change around the year of 1998, a systematic study of the trend turnings in both space and time is needed. We believe that the RSD t test method will make contribution to this kind of climate research subjects.

5 Conclusions

We propose a new methodology, the RSD t test, to relatively objectively detect multiple trend turnings of time series. This method uses a slope difference statistic tslope to test the sub-series trend difference, thereby identifying the turning points. The RSD t test has the capacity to detect all three types (TR, TN, and TD) of trend turning which are discussed above.

In this article, we compare the RSD t test method with some existing methods in an idealized time series case and several climate time series cases. The trend turning detection results of these cases show that the RSD t test method has a superior performance when detecting multiple trend turnings of climate time series. And as we envisioned, the RSD t test method is much more appropriate for identifying TD type of trend turning compared with existing methods.

The new test statistic tslope is a t-distribution slope difference statistic. This statistic tslope can be used for both equal and unequal test samples thereby suitable for detecting trend turning. By replacing the degrees of freedom from the assumption of independent observations to the effective degrees of freedom, the RSD t test method may still be effective when detecting the trend turning in autocorrelated time series. This feature is important because autocorrelation is common in the climate data.

At last, it needs to be pointed out that the research on climate trend turning is still few in the literature. And currently, there has been no general standard for judging different trend turning detection methods. Therefore, the reliability and applicability of the RSD t test also need to be further verified and developed through more climate series analysis in climate change research.

References

Alexander LV, Zhang X, Peterson TC, Caesar J, Gleason B, Tank AMGK, Haylock M, Collins D, Trewin B, Rahimzadeh F, Tagipour A, Kumar KR, Revadekar J, Griffiths G, Vincent L, Stephenson DB, Burn J, Aguilar E, Brunet M, Taylor M, New M, Zhai P, Rusticucci M, Vazquez-Aguirre JL (2006) Global observed changes in daily climate extremes of temperature and precipitation. J Geophys Res 111:D05109. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005jd006290

Andrews WKD (1993) Tests for parameter instability and structural change with unknown change point. Econometrica 61:821–856. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0262.00405

Bartlett MS (1935) Some aspects of the time-correlation problem in regard to tests of significance. J R Stat Soc 98(3):536–543. https://doi.org/10.2307/2342284

Bartlett MS (1946) On the theoretical specification and sampling properties of autocorrelated time-series. Suppl J R Stat Soc 8(1):27–41. https://doi.org/10.2307/2983611

Box GEP, Jenkins GM, Reinsel GC (1976) Time series analysis: forecasting and control. rev. ed. J Time 31(4):238–242

Bretherton CS, Widmann M, Dymnikov VP, Wallace JM, Bladé I (1999) The effective number of spatial degrees of freedom of a time-varying field. J Clim 12:1990–2009. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442(1999)012<1990:TENOSD>2.0.CO;2

Chen XD, Luo DH (2017) Arctic sea ice decline and continental cold anomalies: upstream and downstream effects of Greenland blocking. Geophys Res Lett 44:3411–3419. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL072387

Chen H, Schneider EK, Wu ZW (2015) Mechanisms of internally generated decadal-to-multidecadal variability of SST in the Atlantic Ocean in a coupled GCM. Clim Dyn 46:1517–1546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-015-2660-8

Cheung KKW, Jiang NB, Liu KS, Chang LTC (2015) Interdecadal shift of intense tropical cyclone activity in the Southern Hemisphere. Int J Climatol 35:1519–1533. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.4073

Chu C, White H (1992) A direct test for changing trend. J Bus Econ Stat 10:289–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350015.1992.10509906

Easterling DR, Wehner MF (2009) Is the climate warming or cooling? Geophys Res Lett 36:L08706. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009gl037810

Ebisuzaki W (1997) A method to estimate the statistical significance of a correlation when the data are serially correlated. J Clim 10:2147–2153. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442(1997)010<2147:AMTETS>2.0.CO;2

England MH, McGregor S, Spence P, Meehl GA, Timmermann A, Cai WJ, Sen Gupta A, McPhaden MJ, Purich A, Santoso A (2014) Recent intensification of wind-driven circulation in the Pacific and the ongoing warming hiatus. Nat Clim Chang 4:222–227. https://doi.org/10.1038/Nclimate2106

Feng J, Li JP, Wang YQ, Guo YP (2017) Decreased response contrast of Hadley circulation to the equatorially asymmetric and symmetric tropical SST structures during the recent hiatus. Sola 13:181–185. https://doi.org/10.2151/sola.2017-033

Groisman PY, Easterling DR (1994) Variability and trends of total precipitation and snowfall over the United-States and Canada. J Clim 7:184–205. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0442(1994)007<0184:Vatotp>2.0.Co;2

Hansen J, Ruedy R, Sato M, Lo K (2010) Global surface temperature change. Rev Geophys 48:RG4004. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010RG000345

Huang JP, Xie YK, Guan XD, Li DD, Ji F (2017) The dynamics of the warming hiatus over the Northern Hemisphere. Clim Dyn 48:429–446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-016-3085-8

Hurrell JW (1995) Decadal trends in the North-Atlantic Oscillation - regional temperatures and precipitation. Science 269:676–679. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.269.5224.676

IPCC (2013) In: Stocker T, Qin D, Plattner G, Tignor M, Allen S, Boschung J et al (2013) IPCC, 2013: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 3–29

Ji F, Wu Z, Huang J, Chassignet E (2014) Evolution of land surface air temperature trend. Nat Clim Chang 4(6):462–466. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2223

Jiang J, Mendelssohn R, Schwing F, Fraedrich K (2002) Coherency detection of multiscale abrupt changes in historic Nile flood levels. Pédiatrie 29(8):190–192. https://doi.org/10.1029/2002GL014826

Karl TR, Knight RW, Baker B (2000) The record breaking global temperatures of 1997 and 1998: evidence for an increase in the rate of global warming? Geophys Res Lett 27:719–722. https://doi.org/10.1029/1999gl010877

Kendall MG (1975) Rank correlation methods. Charless Griffin, London

Kosaka Y, Xie SP (2013) Recent global-warming hiatus tied to equatorial Pacific surface cooling. Nature 501:403–407. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12534

Li JP, Wang JXL (2003) A new North Atlantic Oscillation index and its variability. Adv Atmos Sci 20:299–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02915394

Li JP, Sun C, Jin F-F (2013) NAO implicated as a predictor of Northern Hemisphere mean temperature multidecadal variability. Geophys Res Lett 40:5497–5502. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013gl057877

Li JP, Sun C, Ding RQ (2018) A coupled decadal-scale air-sea interaction theory: the NAO-AMO-AMOC coupled mode and its impacts. In: Beer T, Li JP, Alverson K (eds) Global Change and Future Earth-the geoscience perspective. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Liu RQ, Jacobi C, Hoffmann P, Stober G, Merzlyakov EG (2010) A piecewise linear model for detecting climatic trends and their structural changes with application to mesosphere/lower thermosphere winds over Collm, Germany. J Geophys Res 115:D22105. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010jd014080

Maher N, Sen Gupta A, England MH (2014) Drivers of decadal hiatus periods in the 20th and 21st centuries. Geophys Res Lett 41:5978–5986. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014gl060527

Mann HB (1945) Nonparametric tests against trend. Econometrica 13:245–259

Meehl GA, Arblaster JM, Fasullo JT, Hu AX, Trenberth KE (2011) Model-based evidence of deep-ocean heat uptake during surface-temperature hiatus periods. Nat Clim Chang 1:360–364. https://doi.org/10.1038/Nclimate1229

Meehl GA, Teng HY, Arblaster JM (2014) Climate model simulations of the observed early-2000s hiatus of global warming. Nat Clim Chang 4:898–902. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2357

Meinshausen M, Smith SJ, Calvin K, Daniel JS, Kainuma MLT, Lamarque JF, Matsumoto K, Montzka SA, Raper SCB, Riahi K, Thomson A, Velders GJM, van Vuuren DPP (2011) The RCP greenhouse gas concentrations and their extensions from 1765 to 2300. Clim Chang 109:213–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-011-0156-z

Morice CP, Kennedy JJ, Rayner NA, Jones PD (2012) Quantifying uncertainties in global and regional temperature change using an ensemble of observational estimates: the HadCRUT4 data set. J Geophys Res 117:D08101. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011jd017187

Perron P, Zhu X (2005) Structural breaks with deterministic and stochastic trends. J Econ 129:65–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2004.09.004

Ploberger W, Kramer W (1996) A trend resistant test for structural change based on the OLS residuals. J Econ 70:175–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(94)01688-7

Rahmstorf S, Foster G, Cahill N (2017) Global temperature evolution: recent trends and some pitfalls. Environ Res Lett 12:054001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa6825

Santer BD, Wigley TML, Boyle JS, Gaffen DJ, Hnilo JJ, Nychka D, Parker DE, Taylor KE (2000) Statistical significance of trends and trend differences in layer-average atmospheric temperature time series. J Geophys Res 105:7337–7356. https://doi.org/10.1029/1999jd901105

Sen PK (1968) Estimates of the regression coefficient based on Kendall’s tau. Publ Am Stat Assoc 63:1379–1389. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1968.10480934

Şen Z (2012) An innovative trend analysis methodology. J Hydrol Eng 17:1042–1046. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)HE.1943-5584

Smith TM, Reynolds RW, Peterson TC, Lawrimore J (2008) Improvements to NOAA’s historical merged land-ocean surface temperature analysis (1880-2006). J Clim 21:2283–2296. https://doi.org/10.1175/2007JCLI2100.1

Thanasis V, Efthimia BS, Dimitris K (2011) Estimation of linear trend onset in time series. Simul Model Pract Theory 19:1384–1398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.simpat.2011.02.006

Theil H (1950) “A rank-invariant method of linear and polynomial regression analysis,” I, II, and III. Nederl Akad Wetensch Proc 53:386–392, 521–525, 1397–1412. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-2546-8_20

Tomé AR, Miranda PMA (2004) Piecewise linear fitting and trend changing points of climate parameters. Geophys Res Lett 31:L02207. https://doi.org/10.1029/2003gl019100

Toms JD, Lesperance ML (2003) Piecewise regression: a tool for identifying ecological thresholds. Ecology 84:2034–2041. https://doi.org/10.1890/02-0472

Trenberth KE, Fasullo JT (2013) An apparent hiatus in global warming? Earths Future 1:19–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013ef000165

Von Storch H, Zwiers FW (1999) Statistical analysis in climate research, 455 pp. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Vose RS, Arndt D, Banzon VF, Easterling DR, Gleason B, Huang BY, Kearns E, Lawrimore JH, Menne MJ, Peterson TC, Reynolds RW, Smith TM, Williams CN, Wuertz DB (2012) NOAA’s merged land-ocean surface temperature analysis. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 93:1677–1685. https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-11-00241.1

Wang B, Huang F, Wu Z, Yang J, Fu X, Kikuchi K (2009) Multi-scale climate variability of the South China Sea monsoon: a review. Dyn Atmos Oceans 47(1–3):15–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dynatmoce.2008.09.004

Xiao D, Li JP (2007) Spatial and temporal characteristics of the decadal abrupt changes of global atmosphere-ocean system in the 1970s. J Geophys Res 112:D24S22. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JD008956

Xing N, Li JP, Wang LN (2017) Multidecadal trends in large-scale annual mean SATa based on CMIP5 historical simulations and future projections. Engineering 3:136–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENG.2016.04.011

Yao SL, Luo JJ, Huang G, Wang PF (2017) Distinct global warming rates tied to multiple ocean surface temperature changes. Nat Clim Chang 7:486–491. https://doi.org/10.1038/Nclimate3304

Yu B, Lin H (2018) Coherent changes of wintertime surface air temperatures over North Asia and North America. Sci Rep 8:5384. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23750-3

Yu L, Wu Z, Zhang R, Yang X (2017) Partial least regression approach to forecast the East Asian winter monsoon using Eurasian snow cover and sea surface temperature. Clim Dyn 11:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-017-3757-z

Yue S, Wang CY (2004) The Mann–Kendall test modified by effective sample size to detect trend in serially correlated hydrological series. Water Resour Manag 18:201–218. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:WARM.0000043140.61082.60

Zhao S, Li J, Sun C (2016) Decadal variability in the occurrence of wintertime haze in central eastern China tied to the Pacific Decadal Oscillation. Sci Rep 6:27424. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27424

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply thankful to those in the scientific community who have provided data and constructive comments. The HadCRUT4 is obtained from the Met Office Hadley Centre (UK) and can be downloaded from https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadcrut4. The GISTEMP is obtained from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and can be downloaded from https://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp. The NOAA-GT is obtained from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and can be downloaded from https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/data/gridded/data.noaaglobaltemp.html.

Funding

This study is jointly supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFA0601801) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) Projects (41530424, 41790474).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zuo, B., Li, J., Sun, C. et al. A new statistical method for detecting trend turning. Theor Appl Climatol 138, 201–213 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-019-02817-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-019-02817-9