Abstract

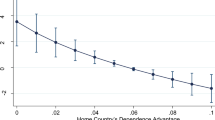

Low productivity is an important barrier to the cross-border expansion of firms. But firms may also need external finance to shoulder the costs of entering foreign markets. We develop a model of multinational firms facing real and financial barriers to foreign direct investment (FDI), and we analyze their impact on the FDI decision. Theoretically, we show that financial constraints can affect highly productive firms more than firms with low productivity because the former are more likely to expand abroad. We provide empirical evidence based on a detailed dataset of German domestic and multinational firms which contains information on parent-level financial constraints as well as on the location the foreign affiliates. We find that financial factors constrain firms’ foreign investment decisions, an effect felt in particular by firms most likely to consider investing abroad. The locational information in our dataset allows exploiting cross-country differences in contract enforcement. Consistent with theory, we find that poor contract enforcement in the host country has a negative impact on FDI decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In the crisis that started in 2007, for instance, an increasing number of German firms reported credit constraints as an impediment to expansion into foreign countries (Deutscher Industrie- und Handelskammertag 2009).

See, for example, Markusen (2002).

We restrict our analysis to FDI and hence do not distinguish different forms of entering a foreign market. Antras et al. (2009) instead study how the choice between FDI and arm’s length contracting is affected by investor protection. Similarly, Carluccio and Fally (2012) investigate how the choice of an importer between sourcing from a vertically integrated firm versus outsourcing to an independent supplier reacts to financial development. In both papers, the overall level of international activity increases with better contract enforcement, as it does in our paper, while the internal solution is predicted to be relatively less likely to be used if the contractual environment improves.

We use data on the balance sheets of firms in Germany merging the Dafne database provided by Bureau van Dijk, and the FDI database of the Deutsche Bundesbank.

Similarly, Muendler and Becker (2010) study the intensive and the extensive margin of German firms’ foreign investment but they look at the employment response to foreign expansions and do not study the impact of financial frictions.

Interestingly, Antras et al. (2009) find that the relative choice of FDI over arm’s length contracting decreases as a function of investor protection, while the overall scale of multinational activity increases. Hence, this does not contradict our finding that the overall level of FDI is increasing in institutional quality. Similarly, Carluccio and Fally show that importing from integrated firms decreases in financial development relative to outsourcing, but that total importing increases. Thus, again this is not in contrast to the message of our analysis that international activity is hindered by underdeveloped institutional environments.

We focus on horizontal FDI. The qualitative implications of our model with regard to the impact of financial constraints would also go through for vertical FDI.

It is straightforward to extend our model and to include an outside option like exports that depends positively on the firm’s productivity. As we show in Buch et al. (2010), the firm’s productivity level matters relatively more for the investment opportunity abroad than for the outside option of exporting. The qualitative results of our model are unchanged.

Harrison et al. (2004) report that financial development lowers financial constraints.

Without loss of generality, we assume that the efficiency loss is the same for both kinds of collateral goods.

This assumes that the firm can hold the bank down to its outside option of liquidating the collateral. It would be straightforward to modify this assumption and let the two parties split the gains from not liquidating the collateral. However, given our assumption of a perfectly competitive banking market, the first assumption seems to be the most convincing one.

Endogenizing the optimal size of collateral is not considered by previous models, as they do not consider liquidation costs and, hence, pledging the maximum collateral is innocuous.

This is robust to allowing for larger multinational companies with internal capital markets, as the contractual environment of the host country affects the functioning of internal capital markets as well.

Note that this result is robust to alternative specifications of the cost function, in particular to assuming constant marginal costs of production like in a standard monopolistic competition model.

The model is estimated using an instrumental variable regression model. Estimates using a simple OLS or probit model are qualitatively similar and are available upon request.

Our dataset does not allow using more structural measures of productivity such as the methods developed by Olley and Pakes (1996) and Levinsohn and Petrin (2003). We cannot follow Olley and Pakes because first, we do not know why firms may leave our dataset, i.e., whether exit occurs for economic or other reasons. Second, because of financial constraints, investment might no longer be strictly increasing in the productivity shock. We do not use the method of Levinsohn and Petrin (2003), because we do not observe intermediate inputs.

Note that in contrast to Manova (2013), who studies export decisions, we consider the case of FDI where the firm has to build a plant in a foreign country. If the parent company has a high share of property, plant and equipment, this also translates into higher fixed costs of market entry, because the affiliate will most likely also have to have a higher share of property, plant and equipment.

Following Kaplan and Zingales (1997), there has been a lively debate on the usefulness of investment-cash flow sensitivities as a measure for financial constraints. The focus of the discussion have been endogeneity issues as well as issues of adequately taking into account access to external finance. See also Brown et al. (2009) for an overview of this discussion.

For a detailed description of count data models, see, for example, Jones et al. (2007).

References

Alvarez, R., & Lopez, R. (2013). Financial development, exporting and firm heterogeneity in chile. Review of World Economics/Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 149(2), 183–207.

Antras, P., Desai, M., & Foley, C. F. (2009). Multinational firms, FDI flows, and imperfect capital markets. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(3), 1171–1219.

Bayraktar, N., Sakellaris, P., & Vermeulen, P. (2005). Real versus financial frictions to capital investment. (ECB Working Paper 566). Frankfurt: European Central Bank.

Bellone, F., Musso, P., Nesta, L., & Schiavo, S. (2010). Financial constraints and firm export behaviour. The World Economy, 33(3), 347–373.

Berman, N., & Héricourt, J. (2010). Financial factors and the margins of trade: Evidence from cross-country firm-level data. Journal of Development Economics, 93(2), 206–217.

Bernard, A., Eaton, J., Jensen, J., & Kortum, S. (2003). Plants and productivity in international trade. American Economic Review, 93(4), 1268–1290.

Bernard, A. B., & Jensen, J. B. (2004). Why some firms export. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 86(2), 561–569.

Brown, J. R., Fazzari, S. M., & Petersen, B. C. (2009). Financing innovation and growth: Cash flow, external equity and the 1990s R&D boom. Journal of Finance, 64(1), 151–185.

Buch, C. M., Kesternich, I., Lipponer, A., & Schnitzer, M. (2010). Exports versus FDI revisited: Does finance matter? (CEPR Discussion Paper 7839). London: Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Carluccio, J., & Fally, T. (2012). Global sourcing under imperfect capital markets. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 94(3), 1–30.

Chaney, T. (2005). Liquidity constrained exporters. (NBER Working Paper 19170). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Deutscher Industrie- und Handelskammertag. (2009). Auslandsinvestitionen in der Industrie 2009. Berlin and Brussels.

Forlani, E. (2010). Liquidity constraints and firm’s export activity. (Development Working Papers 291). University of Milano: Centro Studi Luca d’Agliano.

Greenaway, D., Guariglia, A., & Kneller, R. (2007). Financial factors and exporting decisions. Journal of International Economics, 73(2), 377–395.

Harrison, A. E., Love, I., & McMillan, M. S. (2004). Global capital flows and financing constraints. Journal of Development Economics, 75(1), 269–301.

Helpman, E., Melitz, M. J., & Yeaple, S. R. (2004). Export versus FDI. American Economic Review, 94(1), 300–316.

Javorcik, B. S., & Wei, S.-J. (2009). Corruption and cross-border investment in emerging markets: Firm-level evidence. Oxford: University of Oxford.

Jones, A. M., Rice, N., d’Uva, T. B., & Balia, S. (2007). Applied Health Economics. Oxfordshire: Routledge.

Kaplan, S. N., & Zingales, L. (1997). Do investment-cash flow sensitivities provide useful measures of financial constraints?. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(1), 169–215.

Klein, M. (2012). Capital control: Gates and walls. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2, 317–367.

Levinsohn, J., & Petrin, A. (2003). Estimating production functions using inputs to control for unobservables. Review of Economic Studies, 70(2), 317–342.

Lewbel, A. (2010). Using heteroskedasticity to identify and estimate mismeasurement and endogenous regressor models. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 30(1), 67–80.

Lipponer, A. (2006). Microdatabase direct investment- MiDi. A brief guide. (Bundesbank Working Paper). Frankfurt.

Manova, K. (2013). Credit constraints, heterogeneous firms, and international trade. Review of Economic Studies, 80(2), 711–744.

Manski, C. F. (1993). Identification of endogenous social effects: The reflection problem. Review of Economic Studies, 60(3), 531–542.

Markusen, J. (2002). Multinational firms and the theory of international trade. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Mayer, T., & Ottaviano, G. I. (2008). The happy few: The internationalisation of European firms. Intereconomics: Review of European Economic Policy, 43(3), 135–148.

Melitz, M. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, 71(6), 1695–1725.

Muendler, M.-A., & Becker, S. (2010). Margins of multinational labor substitution. American Economic Review, 100(5), 1999–2030.

Olley, S., & Pakes, A. (1996). The dynamics of productivity in the telecommunications equipment industry. Econometrica, 64(6), 1263–97.

Rajan, R., & Zingales, L. (1998). Financial dependence and growth. American Economic Review, 88(3), 559–586.

Russ, K. (2007). The endogeneity of the exchange rate as a determinant of FDI: A model of money, entry, and multinational firms. Journal of International Economics, 71(2), 267–526.

Russ, K. (2012). Exchange rate volatility and first-time entry by multinational firms. Review of World Economics/Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 148(2), 269–295.

Schindler, M. (2009). Measuring financial integration: A new data set. IMF Staff Paper, 56(1), 222–238.

Stiebale, J. (2011). Do financial constraints matter for foreign market entry? A firm-level examination. The World Economy, 34(1), 123–153.

Wagner, J. (2012). International trade and firm performance: A survey of empirical studies since 2006. Review of World Economics/Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 148(2), 235–267.

World Bank. (2008). World Development Indicators and Doing Business Database.

Acknowledgments

This paper represents the authors’ personal opinions and does not necessarily reflect the views of the Deutsche Bundesbank. This paper was written partly during visits by the authors to the Research Centre of the Deutsche Bundesbank as well as while Claudia Buch was visiting the CES Institute in Munich and the NBER in Cambridge, MA, and Monika Schnitzer was visiting the University of California, Berkeley. We gratefully acknowledge the hospitality of these institutions as well as being allowed access to the Deutsche Bundesbank’s Foreign Direct Investment (MiDi) Micro-Database. We also gratefully acknowledge funding under the EU’s 7th Framework Programme SSH-2007-1.2.1 “Globalisation and its interaction with the European economy” as well as funding by the German Science Foundation under SFB-TR 15 and GRK 801. Valuable comments on earlier drafts were provided by Paul Bergin, Theo Eicher, Fritz Foley, Yuriy Gorodnichenko, Alessandra Guariglia, Galina Hale, Florian Heiss, Heinz Herrmann, Beata Javorcik, Nick Li, Kalina Manova, Assaf Razin, Katheryn Niles Russ, Alan Taylor, Shang-Jin Wei, Joachim Winter, Zhihong Yu, participants of seminars at the Deutsche Bundesbank, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, the University of California (Berkeley, Davis, San Diego), the University of Madison, the University of Munich, the University of Nottingham, the University of Stanford, the University of Washington, Seattle, at the San Francisco Fed, and at the ASSA Meetings in Atlanta. We would also like to thank Timm Körting and Beatrix Stejskal-Passler for their most helpful discussions and comments on the data and Cornelia Kerl, Anna Gumpert, and Sebastian Kohls for their valuable research assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

About this article

Cite this article

Buch, C.M., Kesternich, I., Lipponer, A. et al. Financial constraints and foreign direct investment: firm-level evidence. Rev World Econ 150, 393–420 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-013-0184-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-013-0184-z