Abstract

In Australia, approximately 30% of people diagnosed with HIV are not accessing treatment and 8% of those receiving treatment fail to achieve viral suppression. Barriers limiting effective care warrant further examination. This mixed-methods systematic review accessed health and social sector research databases between November and December 2015 to identify studies that explored the perspective of people living with HIV in Australia. Articles were included for analysis if they described the experiences, knowledge, attitudes and beliefs, in relation to treatment uptake and adherence, published between January 2000 and December 2015. Quality appraisal utilised the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool Version 2011. Seventy-two studies that met the inclusion criteria were reviewed. The interplay of lack of knowledge, fear, stigma, physical, emotional and social issues were found to negatively impact treatment uptake and adherence. Strategies targeting both the individual and the wider community are needed to address these barriers.

Resumen

En Australia, aproximadamente el 30% de las personas diagnosticadas con VIH no están accediendo al tratamiento; el 8% de los que han recibido el tratamiento no logran alcanzar niveles de supresión viral total. Las barreras que limitan la prestación de una atención médica integral y eficaz, necesitan ser examinadas detenidamente. Se realizó una revisión sistemática de los estudios que exploraron la perspectiva de las personas viviendo con VIH en Australia. Se utilizaron métodos mixtos para acceder a bases de datos de investigación en salud y del sector social entre noviembre y diciembre de 2015. Los artículos que se incluyeron para el análisis debían describir experiencias, conocimientos, actitudes y creencias, en relación a la adopción del tratamiento y adherencia al mismo, publicados entre enero de 2000 y diciembre del 2015. La evaluación de la calidad de los artículos utilizó la herramienta de evaluación de métodos mixta, versión 2011. Se revisaron setenta y dos estudios que cumplieron los criterios de inclusión. Las interacciones entre la falta de conocimiento, miedo, estigma, así como problemas físicos, emocionales y sociales produjeron un impacto negativo en la adopción y adherencia al tratamiento. Se necesitan estrategias dirigidas a los individuos, así como a la comunidad en general para hacer frente a estas barreras.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

HIV has claimed over 34 million lives worldwide and continues to impact negatively on the lives of 37 million others who are infected, their families and the community as a whole [1, 2]. Halting the spread of HIV and caring for those infected are among the leading global health and humanitarian concerns [2, 3]. Global health strategies are directed towards ending the epidemic by the year 2030 [4, 5]. While there are no cures for the disease, major advances in medical technology, particularly within the past decade, have resulted in the availability of tools for rapid diagnosis and new classes of antiretroviral therapy (ART) that have more favourable safety and tolerability profiles in addition to greater efficacy in suppressing viral replication [6]. In the fight against HIV, these advances have transformed the status of a person infected from having a terminal illness, to living with a chronic health condition, and provides hope for bringing the epidemic to an end [3, 4].

Research demonstrating effective management of HIV highlights four key areas: (i) early diagnosis, (ii) timely treatment with appropriate medication, (iii) near perfect life-long adherence to the treatment regimen, and (iv) commitment to risk reduction practices [2, 3, 5]. Early diagnosis not only allows for initiation of appropriate treatment to prevent deterioration in personal health, but may prevent an infected person from unknowingly transmitting the infection to others [2, 3]. Correlations between the consistent, appropriate use of antiretroviral medication and decreases in viral replication (leading to a decreased in morbidity and mortality), prevention of drug resistance and restoration and preservation of immune function have also been clearly demonstrated [7–10]. It has been estimated that, in order to achieve these benefits, life-long adherence levels of 95% or more need to be maintained [11]. Transmission reduction strategies on the part of people who are infected and people who are at risk are also central to stemming the transmission between individuals [12]. In addition, treatment as prevention (TasP) has been proposed as a means of securing further reductions in HIV incidence beyond those achieved by current prevention programs [3, 13]. To achieve the goal of ending the epidemic by 2030, world health authorities have set a global target of at least 90% diagnosis, treatment uptake and treatment adherence among all people living with HIV [5].

In Australia, it is estimated that approximately 27,150 people (0.14% of the population) currently live with HIV infection [14]. The Australian Government’s framework for the management of the disease is aligned with the goals of the global health community, and reflects the need for timely and equitable access to testing and treatment, for measures to support medication adherence and for the promotion of risk reduction practices to limit the transmission of the virus [15]. While Australia can be considered to be performing relatively well when compared to other developed nations such as the United States and the United Kingdom [16], Australia still falls short of reaching either the global goal or domestic targets [5, 15].

In the Australian health and social context, there are laws to ensure that human rights and access to services for residents and visitors are protected [17]. A diverse range of awareness-raising campaigns and services that adopt interprofessional models of care have been developed and implemented with the aims of halting the HIV/AIDS epidemic and providing care for those affected [15]. Residents (and visitors from countries that have reciprocal agreements with Australia) are able to access diagnostic tests in accredited community-based settings at a subsidised price through the Medicare universal health insurance schemeFootnote 1 [18]. The cost of antiretroviral medication is also subsidised, through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme [19]. It is important to note that relatively modest co-payments are required from the individual for both testing and antiretroviral medication [20]. However, surveillance statistics highlight key areas that are a cause for concern [14]. Specifically, while the prevalence of HIV has stabilised over the past few years, this rate represents the highest level seen over the past 20 years. Furthermore, at the end of 2014, it was estimated that approximately 12% of the people infected with HIV remained undiagnosed. Of the newly diagnosed cases, 28% were deemed to be at “late-stage”. That is, this group of people has been carrying the virus for at least four years without being aware of their status [14]. Among people diagnosed as living with HIV, almost 30% were not receiving antiretroviral treatment [14, 15]. For those who elected to receive treatment, up to 10% failed to achieve adequate adherence and consequently, failed to achieve viral suppression [15].

HIV transmission rates in Australia are highest among men who have sex with men (MSM), as a result of unprotected sexual contact [14, 21]. Research indicates that the rate of testing among this group has been declining over the past 10 years [21]. Among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people the rate of diagnosis has been increasing over the past five years with transmission through injecting drug use and heterosexual contact higher when compared to the Australian born non-Indigenous population [14]. Among people who were diagnosed late in their progression of the disease, the majority were migrants born in South East Asia or Sub-Saharan Africa [15]. Other groups identified to be at greater risk of HIV infection are people who have travelled overseas and mobile workers, sex workers, people who inject drugs and people in custodial care [15]. These statistics suggest that the core messages concerning the need for early detection, appropriate treatment and perhaps prevention measures, are not reaching some of people living with HIV (PLHIV), and people who are most at risk. It is important therefore, to identify the personal motivations and barriers, both perceived and experienced, that impact on the behaviour of PLHIV and people at risk, in relation to testing, treatment uptake, medication adherence and risk reduction practices. This information will be valuable for policy makers at the domestic level in formulating approaches that target the key areas of need if Australia is to optimise care for those who live with HIV and ultimately mitigate the transmission of infection among people living in Australia [15]. This mixed-methods systematic review is guided by the overarching research question: What factors influence people living with HIV and at risk individuals in making decisions regarding testing, treatment uptake, treatment adherence and exposure prevention? The study is presented in three parts. This first part focuses on understanding the factors that influence decisions regarding treatment uptakeFootnote 2 and treatment adherenceFootnote 3 among PLHIV in Australia. In studies to follow, the literature will be reviewed to facilitate understanding of factors that contribute to suboptimal testing, and to risk taking behaviours among PLHIV and among those who are deemed to be at risk of exposure.

Methods

Study Design

Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies were reviewed. Specifically, quantitative studies were assessed to provide information regarding the demographic characteristics of PLHIV in Australia, their knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about HIV, ART and treatment outcomes and to determine whether there were patterns of associations between these intrapersonal variables and their treatment uptake and adherence behaviours. Qualitative literature that explored participants’ lived experiences was also assessed utilising the principles of thematic analysis [22] to provide a more nuanced understanding of the determinants of these phenomena than could be discerned from the quantitative data alone [23]. The purpose of this research is to provide a greater understanding of the perspectives of PLHIV and to identify motivations and barriers to treatment uptake and adherence.

Search Strategy

Health and social sector research databases: Ovid Medline, CINAHL, Scopus, Health and Society Database, and Sociological Abstracts were accessed between November and December 2015 to identify published studies that described HIV/AIDS care in Australia from the perspective of individuals living with HIV/AIDS. The search involved the use of the keywords: Australia, HIV, knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and barriers. The use of these broader terms allowed the identification of studies focused on treatment uptake and adherence in the Australian context. The electronic search strategy followed a similar pathway as exemplified by Table 1.

A Google search was undertaken to identify grey literature (such as Australian Government publications, periodicals, monographs, surveillance data) to facilitate understanding of Australian health and social contexts.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Articles were considered for analysis if they described the experiences, knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of people living with HIV in the Australian context, in relation to one or more of the following: i) living with HIV, ii) treatment uptake and iii) treatment adherence. To further contextualise the findings relative to the modern Australian setting, studies published prior to the year 2000 were excluded and the latest articles reviewed were published before December 15 2015. Review articles and grey literature were excluded from analysis but their reference lists were scrutinised and in some cases, yielded new articles to include in the analysis.

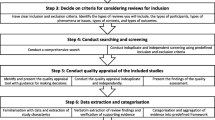

The Review Process

Articles uncovered from the five data base searches were combined and duplicate articles were removed. The title and abstracts of the articles were assessed by the primary author (AM) for their content and relevance to the objectives of the review. Only articles meeting the inclusion were retained. Abstracts were also reviewed by SD to identify any articles that were missed for inclusion into the study. The full-text of the remaining articles were read by AM and those that did not meet inclusion criteria were removed from the review. SD reviewed a random sample of the excluded articles as a measure of quality assurance to prevent relevant articles from being excluded.

Methodological Quality Appraisal

Quality appraisal utilised the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2011 which, although relatively new, has demonstrated efficiency and reliability [24]. This tool was chosen because it allowed for the methodological quality of different types of studies to be evaluated using a one-page questionnaire. The tool was adapted for the purpose of the current review as presented in Table 2.

Quantitative studies were assessed according to four domains. Categorisation varied slightly depending on whether the study was a) a randomised controlled trial (RCT), b) a non-randomised study or c) a descriptive study. For example, the quality of RCTs was judged based on: i) clarity of the randomisation process, ii) clarity of the allocation concealment, iii) completeness of outcome data (≥ 80%), and, iv) level of dropout (< 20%). Mixed methods studies were assessed according to: i) appropriateness of the research design, ii) appropriateness of triangulation, and iii) appropriate acknowledgement of limitations. For qualitative studies, methodological quality was assessed according to the relevance/appropriateness of four domains relative to the research question: i) the data source ii) the analytical process, iii) the findings and iv) reflexivity. Given the diversity of the studies included in this review, only research articles published in peer-reviewed journals were included in the analysis. The search strategy, data table and study quality assessment were reviewed by SD and disagreement resolved by consensus.

Data Extraction and Analysis

The content of each study was reviewed by AM. Data were extracted and tabulated as follows: First author and year of publication, study aim, method, location, participant, and key findings. For qualitative studies and using the principles of thematic analysis [22], AM documented the themes that emerged from the data. A random selection of articles was independently reviewed by SD, who, using the same analytical procedure, thematically recorded the findings. The two authors each developed a code book, then discussed their views and agreed on a coding framework. AM thematically analysed the remaining articles and summarised the results according to the framework. The remaining authors each reviewed 5 articles relative to the framework and provided feedback. Feedback was discussed during team publication meetings and decisions were made based on the outcome of the discussion.

Results

A total of 1148 articles were identified through database and other searches. The process of review and elimination followed the PRISMA guidelines [25] as illustrated in Fig. 1, identified 72 articles for inclusion in the current study. Of the included studies, 34 used quantitative methods including cohort and cross-sectional designs, analysis of medical records and retrospective analysis; 30 used qualitative methods, including focus groups and semi-structured interviews and 6 used both quantitative and qualitative methods. One case report and one short communication article were included due to the insights they offered that were lacking from the findings of the peer-reviewed studies.

Scope

Table 3 summarises the pool of research that has explored the perspectives of key population groups, including PLHIV in general [26–69], MSM and bisexual men [70–82], Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People [83–85], immigrants from high prevalence countries [86–91] and other under researched populations [92–98], with regards to treatment uptake, adherence, and living with HIV in the Australian context.

Apart from those involving PLHIV as a group (n = 42), studies involving MSM (n = 16) were most common. Participants ranged in age from 16 to over 65 years and were able to provide full informed consent. Consistent with the population profile of PLHIV in Australia, the majority were male, homosexually identified and had lived with HIV for at least 12 months. Participants’ socioeconomic status were wide-ranging, even within key populations, and including people living below the poverty line through to individuals with high incomes.

Quantitative studies (n = 34) reported participants’ demographics and socioeconomic status, used a range of psychometric tools (some of which have been previously validated) and dichotomous or multiple choice questions to assess the knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of PLHIV, and used statistical methods to investigate relationships between these as well as observed or self-reported behaviours [26–46, 60–63, 65, 68, 70–73, 79, 81, 98]. Narrative data derived from interviews, group discussions and open-ended questions (n = 30) were used to explore treatment decisions that were poorly explained by quantitative means [47–49, 51–55, 64, 66, 69, 74–78, 80, 82–87, 90–96]. These studies directed enquiries towards lived experience, exploring perceptions of the past, present and future to draw on themes that interplay in the decision making process and provide insights about the motivations and barriers to treatment uptake and adherence. Six studies used both quantitative and qualitative tools to collect and analyse data from participants to further facilitate understanding of the perspectives of PLHIV [56–59, 67, 97]. In addition, one case report [88] and one letter to the editor [89] were included in the review as they offered insights about living with HIV that were not adequately reflected in the published studies. Findings from analyses of the studies are presented below according to the methodology used. The methodological quality ratings of the articles are presented on Table 4. Finding from the review process are summarised in the following sections according to the methods used.

Determinants of Uptake and Adherence Behaviour Identified by Quantitative Means

Quantitative studies are summarised below according to the intrapersonal domains assessed and correlations between these and treatment uptake and adherence behaviours.

Knowledge

Studies seeking to assess the knowledge of PLHIV (n = 5), explored aspects of care such as biomedical treatment [26], information recall [57], disease state [43], and social support services [35, 97]. Methods of assessment mainly required participants to answer Yes/No or to indicate True/False to statements describing aspects of the items being assessed. One study reported that among PLHIV, information regarding ART and the management of HIV were most commonly accessed through general practitioners and HIV specialists, while information about living with HIV was obtained from community support organisations and HIV-positive friends [35]. Overall, these studies highlight that knowledge of support services among PLHIV was poor. Information and support were important in both treatment uptake and adherence decisions, as reflected by participants’ narratives in the section to follow.

Attitudes and Beliefs

The attitudes and beliefs of PLHIV (n = 10) were generally assessed using validated tools, many of which were Likert-type items that required participants to rate their level of agreement with statements depicting the nature of the disease prognosis and aspects of HIV management such as the role of ART, the effectiveness of ART, and the benefits and risks of using ART [26, 28, 33, 34, 58, 70, 79]. While the majority of studies reported that PLHIV believed ART to be effective in suppressing viral replication, that treatment should be initiated early and supported the use of treatment as prevention, they were highly sceptical about the effectiveness of ART in being able to reduce viral transmission and were highly concerned about long-term consequences of ART. Specifically, participants expressed strong beliefs that the long term side effects of ART were not fully understood and/or disclosed, or both, by the medical profession and the pharmaceutical industry. Conversely, there was strong belief among PLHIV regarding the effectiveness of a range of complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs) such as herbal remedies and acupuncture in buffering the negative side effects of ART and restoring health [28, 54, 59, 68]. Conflicting attitudes and beliefs appeared to compound the traumatic impact of diagnosis, influence decisions regarding treatment and adherence, and complicate navigation of living with HIV.

Experience

Validated tools were also used to gather information about participants’ lived experiences (n = 17), which include experience of stigma and discrimination, medication side effects, living with co-existing illness, and social and economic bearing of living with HIV that subsequently impacted on treatment uptake and adherence behaviour [26, 28, 32–34, 37–44, 46, 57, 72, 73]. These studies revealed that the vast majority of PLHIV had been subjected to stigma and discrimination from multiple sources including health care providers when accessing health and support services as a result of disclosure, live with a number of co-morbidities requiring multiple medication, had experienced a high degree of intolerable medication-related side effects, lived with a range of physical, emotional and financial challenges, were engaged in a range of negative social behaviours (such as alcohol and other substance use), and were not always adherent with treatment recommendations. These experiences had a range of negative consequences on treatment uptake and adherence as discussed below.

Correlates of Behaviour

Studies revealed that a lack of knowledge, scepticism about the effectiveness of ART, high levels of fear about medication side effects (both experienced and perceived) and substance use (alcohol and drugs), were negatively correlated with both treatment uptake and adherence [32, 33, 43, 58]. Indeed, two studies found fear of medication side effects to be the most commonly reported barrier among participants and demonstrated it to be an independent factor contributing to decisions not to access ART [31, 32]. Other studies found that uncertainties about the long term effects of the medication [58], as well as a lack of belief in treatment efficacy and a distrust of biomedicines related to questions about the integrity of information sources, particularly those provided by pharmaceutical companies [28], were also correlated with delay/refusal of treatment.

Intolerable side effects, difficulties in managing the treatment regimen, concurrent use of alcohol and other drugs, a high burden of chronic co-morbidities, and difficulties in meeting medication related costs were found to be associated with poor adherence [33, 37, 57]. For example, one study found approximately 85% of PLHIV had at least one co-existing illness and some had up to six additional health conditions [29], while another study reported 52% of respondents were taking prescribed medications in addition to ART [35]. The burden of managing these co-morbidities is considerable with one study reporting that approximately 50% of PLHIV had a pill burden of greater than 10 per day [97]. The prevalence of economic disadvantage with subsequent dependency on government benefits as the main source of income is also high [31, 33, 35]. In a study to explore the impact of medication cost on ART uptake and adherence behaviour, almost 15% of participants reported they had delayed purchasing their medication and 9% reported that they had ceased taking their medication, because they were unable to meet the required costs [40]. During treatment interruption, viral load was demonstrated to rebound to levels comparable to those measured prior to treatment initiation [36]. Another study found that people who had a history of smoking and excessive alcohol consumption had a higher rate of treatment failure than non-smokers and those who consumed no alcohol [30].

In addition to medication-related barriers, the majority of PLHIV reported having received services delivered with stigmatising and prejudicial undertones from health professionals and health care workers when accessing health and social support services [35, 44, 72, 73]. Furthermore, self-stigmatising attitudes and beliefs appeared to heighten the vulnerability of PLHIV to anxiety, stress and depression and to impact negatively on health seeking behaviours, resulting in reduced physical and psychological health, social isolation and quality of life [27, 35].

The studies also identified a range of practices that resulted in suboptimal adherence, which appear to be underpinned by attitudes and beliefs about detrimental long-term effects of ART [34, 38]. For example, one study reported non-adherence to be a deliberate decision to break from treatment in order to spend time away from medication, participants citing reasons to be based on lifestyle or clinical indications [34]. A break from treatment was perceived to enable the body to recover from the negative consequences of taking ART. This study also demonstrated those who took breaks citing lifestyle reasons were more likely to report recreational drug use. Indeed, a number of studies have demonstrated concurrent use of alcohol and other drugs to increase non-adherence [30, 36, 38, 97]. In a study involving PLHIV who were non-adherent, 60% reported they sometimes simply “forgot” to take their medication, 25% reported that they sometimes did not take their medication when they were feeling unwell and 11% reported that sometimes they did not take their medication when they were feeling better [65]. These behaviours may also be underpinned by negative attitudes and beliefs and inaccurate knowledge about ART, as well as psychosocial and psychological issues. Willingness to access ART and to adhere to treatment were shown to be higher among those who feared transmitting the infection to their partners. Treatment adherence was shown to improve after a targeted intervention to improve medication specific knowledge and provided practical assistance in managing the treatment regimen, including the provision of unit dose packaging and reminder text messages [60].

Insights Gained from Qualitative and Mixed Methods Studies

Qualitative studies revealed a complex network of interrelated themes centred on emotional and physical challenges that intertwine with hopes and dreams to motivate a person, or to prevent them from optimising their treatment uptake and adherence behaviours [47–49, 51–55, 64, 66, 74–78, 80, 82–87, 90–96]. Being diagnosed as HIV positive was generally described as “shocking”, “traumatic” and “utterly devastating” and the point at which participants’ perceptions of the world were permanently changed. For some, diagnosis meant an end to a life that once held so much promise. For others, it was the undoing of roadmaps at a time when directions for a better life were starting to unfold. For a small minority, diagnosis was thought to be inevitable, given their involvement in high risk behaviours. Nonetheless, the impact of a positive diagnosis often manifested as sadness and distress caused by fears of impending death, fears of potentially having caused harm to others, fears of being judged and rejected, as well as fears of perceived harmful consequences of a life-long reliance on medication. While some spoke of religious faith and faith in the effectiveness of modern medicine, living with the knowledge that they were infected was, at the very least, extremely difficult [27, 48, 49, 52, 54, 55, 66, 75, 80, 82, 86, 97]. Many revealed that they had very little knowledge related to treatment at the time of diagnosis [55, 80, 86, 95], and spoke of treatment uptake and adherence in the context of attempting to balance competing ideas about illness and health, and trying to come to terms with living with HIV [64, 74, 83, 93]. Irrespective of their background or how they came to be infected, these narratives spoke loudly of the interplay of feelings of fear in relation to stigma and discrimination, the known and unknown impact of treatment, the role of ART in the management of their health and of their enduring hope for a “normal” future [52, 54, 77, 83, 86, 92].

Fear of Stigma and Discrimination

Stigma and discrimination were commonly reported, to varying degrees, from a variety of sources including family, health care providers and participants themselves [51, 52, 76, 77, 80, 82, 83, 86, 89, 90, 92, 93]. These experiences impacted on the way people perceived themselves, their decisions about disclosure and, subsequently, their treatment uptake and adherence. In a study among MSM, participants spoke of the importance of image, where diagnosis served to change one’s status from being healthy and desirable, to unhealthy and undesirable [76]. The fear of being viewed as undesirable and rejected were echoed loudly, particularly among the young and newly diagnosed. Another study among MSM reported that for men who were not in established relationships, decisions about disclosure weighed heavily given that both disclosure and non-disclosure could be seen as having equally devastating impacts [80]. For those in established relationships, serodiscordancy compounded fears of rejection if a partner chose to end the relationship and of self-loathing related to perceptions of one’s own infectiousness and the potential for being a source of harm to the person they loved should the relationship endure.

Studies among migrant populations suggest the fear of being stigmatised following diagnosis appeared to be grounded in cultural beliefs that link the infected person with sexual and moral deviance [86, 89, 90]. These fears were compounded by their own experience of seeing the infected people as being subject to stigmatising, discriminatory and prejudicial behaviours such as people’s reluctance to share eating and drinking utensils, as well as being insulted and called derogatory names. Among those whose citizenship status in Australia was uncertain, fear of deportation and impending death due to discontinuation of treatment and other mental health issues such as anxiety and post-traumatic stress, compounded the emotional turmoil of diagnosis [86]. High levels of anxiety associated with fears of having unknowingly transmitting the infections to others, particularly children, were also widely held, given that members of this group are often diagnosed late [92, 97, 99]. In a study involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, participants revealed that they feared being found to have the medication, which would result in unwanted disclosure and subsequent negative labelling and rejection by their community [83, 90]. In a study involving heterosexual men, diagnosis and subsequent disclosure was associated with a fear of being incorrectly identified as gay [100].

Participant narratives provide valuable insights into how stigma, both perceived and experienced, was navigated by people living with the infection. For example, in the study involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, fear of unwanted disclosure, which was a common occurrence, was associated with being in possession of medication and a lack of privacy for medication storage and administration [83]. Some participants felt forced to resort to hiding medication from others in the household. For others, this fear prevented them from accessing treatment altogether. Among migrant populations, there were widely held beliefs of needing to conceal a positive status in order to avoid stigma associated with the disease. In addition, language difficulties and unfamiliarity with the health and social service systems presented further barriers to accessing care [86, 89]. Ultimately, some did not access care, including treatment, despite a desire to do so. Among heterosexual men, the effort to avoid being labelled as gay prompted some to take measures to ensure non-disclosure, including delaying or rejecting treatment [100].

Living with HIV also had a range of physical impacts, which served to bear further on experiences of stigma and discrimination [48, 78]. For example in a study of PLHIV who were experiencing extreme fatigue, participants reported additional pressure was placed on their relationships as a consequence of not being able to fulfil household duties such as cooking, and cleaning. Fatigue also negatively impacted on their ability to fulfil their employment obligations and ignited fears that having to take frequent breaks would cause suspicion and/or disclosure of their HIV status to colleagues [48]. This was further exacerbated by frustration related to a perceived lack of understanding by health workers, who reportedly misdiagnosed the condition as depression. Not being able to contribute fully and de-validation of the depth of suffering served to undermine feelings of self-reliance and negatively impacted on assessment of self-worth. Consequently, there was a tendency to withdraw from social and employment relationships that further compounded the feelings of worthlessness, self-stigma and isolation.

Fear of Medication Side Effects

Alongside fears about stigma and discrimination, participants expressed a high level of concern about side effects of treatment that was further compounded by a lack of medication-specific knowledge [51, 69, 74, 80, 92, 93]. Different population groups expressed fears about different aspects of medication side effects. For example, one study involving MSM reported a fear of diarrhoea and vomiting, a known side effect of some early ART regimens, to be associated with an image of being “dirty” and “soiled” [80]. This resulted in greater weighting being placed on quality of life without medication than increased longevity offered by treatment. In comparison, among women taking ART for prevention of vertical transmission, fears were directed towards the potential toxicity of the medication to the developing baby [92, 93, 97]. While the majority accepted treatment, the negative impact of their decision was evident in their narratives. For some, adherence to treatment recommendations diverged from their cultural and societal expectations. This divergence was perceived as discrediting them as mothers and some elements, such as avoiding breastfeeding, were in conflict with own beliefs and desires. Consequently, acceptance of these practices carried the risk of unwanted disclosure, with subsequent stigma and discrimination within their communities. A number of women reported they were forced to develop alternative stories to justify accepting treatment. The narratives of these women indicated they experienced fear, guilt and disappointment, and were frustrated at not feeling listened to by health professionals who were seen to be solely focused on treatment according to established guidelines. This is not to detract from the fear experienced by MSM, many of whom had seen friends and loved ones experience toxic effects of early treatments and held strong beliefs that not all long-term effects of current therapy are known or are not being disclosed [80]. Scepticism about reports of reduced infectivity after absolute life-long adherence was cited by some who argued that there was insufficient evidence to warrant beginning treatment [32, 80].

These studies provide valuable insights about the influences that impact on decisions regarding disclosure, treatment uptake and treatment adherence, highlighting the heavy toll of fears, as well as the tendency of some PLHIV to disconnect from social and personal relationships as a means of protection from these fears. These studies also convey the ongoing uncertainty that some individuals live with in relation to both known and unknown side effects as a result of accessing treatment.

The Role of ART

Decisions regarding treatment uptake and adherence are complex and multifaceted. They appear to be influenced by an individual’s beliefs about the effectiveness of ART, as well how they view themselves in relation to the disease [32, 49, 51, 58, 74, 79, 80, 84, 93]. For the majority of participants, ART was perceived as integral to managing life with HIV. Beliefs that ART was effective in suppressing viral replication (and thereby restoring health), reducing infectiousness and preventing infection to others underpinned decisions to start treatment. However, some viewed treatment uptake as conceding or surrendering control to HIV [41, 51, 74, 80, 92, 93]. Fears appeared centred on perceptions that ART could diminish one’s sense of health and wellbeing due to concerns about intolerable side effects as well as anxiety about potential for harmful effects yet unknown [51]. That is, medication side effects might limit respondents’ capacity to fulfil their parental duties and employment and social obligations as well as cause long term damage to their body. Some believed their current experience of wellbeing was due in part, to their decision to decline treatment thereby allowing their immune system to do battle with the virus as nature had intended. Personal qualities such as inner strength and self-awareness were perceived by some to enable them to be in-tune with their own body. For these people, HIV was seen only as a potential issue that did not have to be acknowledged or addressed until treatment became “necessary” [74]. Others appeared to have felt pride in resisting treatment. A sense of satisfaction was reported in being able to maintain clinical markers within “healthy” range independent of medication, and respondents were committed to maintaining health through lifestyle measures such as diet, exercise and the use of complementary and alternative therapies [80]. Among these participants, treatment was commonly reserved for a time when they perceived that their body could no longer handle the virus on its own.

Along similar lines, accepting treatment was seen to impact negatively on morale and, consequently, on respondents’ ability to maintain good physical and mental health [74]. Being chained to a life-long commitment to the treatment regimen was assessed by some to be unmanageable given their personalities and personal circumstances [80]. Some assessed treatment as low priority when other concerns, such as managing family or attending to a sick partner, demanded their immediate attention [51]. Furthermore, negative emotions evoked by the physical act of taking medication served as constant reminders that participants had the infection and needed to rely on medication for the rest of their lives [32]. Therefore, treatment uptake was perceived as conceding to the virus and relinquishing power over current ways of life. These participants also expressed preference for allowing their own immune system to adjust to, and resist, HIV.

Others reported lacking the level of knowledge required for making treatment decisions and expressed a reluctance to become more knowledgeable due, in part, to feelings of being already overwhelmed by learning that they are HIV positive and by day to day issues of living with HIV [51, 80]. These individuals perceived doctors to possess expert knowledge and expressed a wish for their doctors to lead treatment decisions. Insufficiently strong recommendation from doctor was provided as an explanation for their decision to delay or reject treatment. With heightened fears of medication side effects as previously discussed, some simply chose to delay treatment until improved options with better safety and tolerability profiles became available. Some who were asymptomatic, expressed a wish not to suffer side effects unnecessarily, given their current perception of good health [74]. Some also perceived themselves to be genetically superior in their ability to fight the virus and believed they would avoid the need for ART altogether, while others were waiting until they observed clinical evidence indicating a need to start treatment [51].

Further insights into individual views about the role of ART were demonstrated in their narratives regarding the role of CAM in the management of HIV [28, 49, 53, 54, 59]. Some participants expressed a belief that ART were chemicals with toxic effects and their use in the management of HIV was unduly influenced by pharmaceutical companies who had questionable motives [49, 51]. In contrast, they believed CAM to encourage holistic healing through embracing the mind and body connection, thereby encouraging physical, emotional and psychological health [49]. Thus, while ART initiation was seen as admission of impending death, CAM was viewed as being able to strengthen the body’s ability to overcome the virus, thereby delaying disease progression. Perceptions of ART as a daunting imposition on day to day life and with the threat of viral resistance still looming in the background despite these efforts, provided some with further disincentive for use. These perceptions appear to have been formed by experiences seeing health professionals evaluate ART success as being the absence of symptoms, low viral load and favourable CD4 counts, with perceived disregard for how an individual might see their situation, health, or quality of life. Reinforced by their experiences of “quick transaction” type relationships with health professionals compared with their often enduring relationship with CAM practitioners, such as massage therapists, acupuncturists and naturopaths, these factors gave rise to perceptions of conventional approaches to HIV management as dehumanising, focusing on the virus and not the person. In addition, there was strong belief in the effectiveness of CAM as a means of negating a range of perceived negative side effects of ART [28]. Furthermore, the effectiveness of CAM appeared to be assessed not according to its ability to treat the virus, but rather in its ability to nurture the body and mind to enable it to fight the virus [49]. This is particularly evident in narratives that highlight perception of health among PLHIV whose objective clinical markers indicated otherwise. These perceptions facilitate understanding of the high prevalence of CAM use among PLHIV, and may provide an explanation for why some people choose to reject ART and use only CAM.

Narratives describing treatment adherence tell of the interplay between perceptions of an unmanageable treatment burden, such as the relentless demands of the treatment regimen, intolerable medication side effects (both experienced and perceived), and the impact of emotional, psychological and social issues such as isolation, depression and alcohol and other substance use [49, 58, 74, 80, 92, 93, 101]. While life before HIV diagnosis was remembered by some as the ‘good times’, there was also underlying belief that risk-taking behaviours may have paved the way to becoming infected [85, 96]. For example, in a study involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People, the use of alcohol and other substances was identified as a key factor in acquiring HIV, with a sense of loss of control being central to exposure [85]. However, while alcohol and other drugs continued to be used, most acknowledged that the substances provided only temporary comfort, did not solve their problems, and in some cases, made the situation worse. Denial was also commonly expressed as a means for stopping the experience of living with HIV from being overwhelming and to becoming the central focus of identity.

In the difficult times following diagnosis, many relate their risk-taking behaviours to subsequent non-adherence [75, 85]. For example, some reported stopping medication when using recreational drugs and when drinking heavily. Behaviour that resulted in non-adherence also appeared to be linked to their perceptions about adherence. For example, one participant argued that they maintained adherence by reconciling doses missed during periods of heavy drinking with ‘catch up’ doses afterwards [85]. Another participant omitted doses in order to ‘save’ them for continuation of therapy should the person subsequently face deportation [86]. Parents administering ART to their children identified difficulty in managing the treatment regimen, inability to prepare the medication according to mixing instructions, the unfavourable taste of the medicine and fear of long-term side effects as resulting in omission of doses, thereby impacting on therapy [57].

Treatment delays or rejection, denial, alcohol and other substance use were commonly reported among PLHIV as means of coping with the stresses of life with HIV that further compounded health, financial and social problems. However, despite these beliefs and behaviours, the majority expressed stronger fears about the consequences of remaining untreated. Furthermore, and in contrast with the perceptions of ART previously discussed, some viewed treatment uptake as being proactive in taking control of their bodies and not allowing the virus to replicate unchecked, in addition to being a means of protecting others from the disease, and viewed ART as an intervention through which one can hope to live a normal life.

Hope for a Normal Future

Narratives following diagnosis that describe embracing a life with HIV suggest acceptance that although far from ideal, life was manageable and highlight the central role of ART in achieving this [48, 51, 55, 80, 83, 85–87, 92, 93, 101]. The desire to be treated ‘like normal’ was universal, along with an emphasis on taking personal control of life through self-care, both physical and emotional. Furthermore, a desire to live in combination with social and spiritual support appeared to buffer the experience of living with the illness, and to prompt behavioural change [51, 85, 86]. Narratives commonly told of attempts to live a normal life despite diagnosis by directing thinking towards the future. Desires were expressed in terms of commitment to fulfilling personal goals such as maintaining health, having a successful career and children. Self-care included steps individuals had taken towards improving their health through appropriate housing, improved nutrition, reducing alcohol intake and strengthening social and family connections, as well as to taking ART. The initiation of therapy was perceived not only to reduce their own viral load, with consequent improvement in health, but also to contribute to reducing the burden on the community.

Taking control for maintaining health through positive treatment uptake and treatment adherence behaviours were seen to encourage personal growth, possibly by drawing on inner strength [55, 85]. Indeed, self-perceived inner strength was credited for being able to overcome many barriers, given the negative changes in life circumstances as a consequence of being infected. For some, taking responsibility also meant self-regulation, including disengagement from social interactions that had encouraged risk-taking behaviours [85]. This perception of being able to take back control served to empower people to make further changes to improve their physical, emotional and psychological health.

The belief that everyday experiences of health and illness can be directly influenced by frame of mind was also prominent [83, 84]. Deliberate actions taken to overcome challenges imposed by HIV (such as fatigue and addressing fears such as disclosing status) were seen to contribute to an optimistic outlook, including being more focused on goals and having greater purpose in life [48, 80]. Maintaining optimism, self-affirmation and self-value empowered individuals to change their perspective and was seen as a means of defeating the negative impact of the disease. Hope for the future was seen as the pivotal point through which one chose to either be dying, or to be living with HIV.

Discussion

The Australian health system has recently implemented changes to the rules and regulations concerning the prescribing and dispensing of antiretroviral medication with the aim of improving treatment uptake and adherence through better access [102]. In addition, the licenced use and funding for PrEP is currently under consideration [103]. At this pivotal time, it is prudent to reflect on the voices of Australians living with HIV in order to identify their specific needs and the barriers that limit optimal care.

This review reveals that there are gaps between the services that are currently available and those necessary for optimal treatment for PLHIV, and that the burden of the disease is far reaching, with detrimental consequences to the individual beyond what can be attributed to the virus alone. The need for information about treatment and the availability of support organisations, particularly during the early stages after diagnosis was highlighted alongside the need for information to be disseminated across the broader community. Specifically, more resources for vulnerable groups such as pregnant women and migrants are needed. The wish for information (and services) to be delivered in a manner that is non-threatening and takes into consideration the individual’s personal, cultural and religious beliefs has also been clearly expressed. Contextualised information regarding the side effects of medications and how to manage them is particularly lacking. Insufficient knowledge and subsequent fears related to side effects impacted negatively on both treatment uptake and adherence. In light of the new ARTs that have more favourable safety and tolerability profiles, contextualised information may be a means of encouraging both. When individuals received information and care in the absence of negative judgement, they were better able to make informed decisions and to maintain a sense of self-worth amid the emotional challenges, particularly soon after their diagnosis when their knowledge of disease management is low and they are particularly vulnerable. The need for health professionals to deliver individualised care without prejudice has been clearly highlighted.

Information and service delivery must also consider the needs of populations such as those who lack English proficiency and may lack the skills required for navigating the health system and social support networks. Consideration must also be given to the cost structure around medication, given the vast majority of PLHIV also live with co-morbidities, which impact on them emotionally, physically and financially and were identified to impose considerable hardship that resulted in suboptimal treatment uptake and adherence. Research should be directed towards identifying the specific information and service needs among key population groups in order to develop information resources that address the areas of deficiency.

Stigma and discrimination were commonly perceived and experienced and impacted negatively on disclosure, treatment uptake and adherence. While arguably treatment uptake and adherence can be ultimately deemed to be the responsibility of the individual, it is clear from the narratives that stigma and discrimination are insidious and ingrained at the personal, health system and wider community levels, and manifest as major barriers to accessing care. Attempts to guard one’s self from the impact of stigma and discrimination only served to isolate further people who are already vulnerable, thereby depriving them from what might have been their intended course of action in the absence of fear. Strategies that address the stigmatising attitudes and beliefs held about people who are infected are also needed. These strategies should target members of the health professions, support organisations and the community at large, as well as the individuals themselves since self-stigma also appears to be prevalent among PLHIV. The importance of connectedness within personal relationships and with the community, were clearly demonstrated to buffer the negative effects of living with HIV. Thus, strategies to reduce stigma and discrimination should also aim to engage PLHIV with the community at large and vice versa. These strategies must be informed by research that seeks to understand the underlying reasons, at both the individual and community level, for stigmatising attitudes and beliefs.

Strategies to address social issues such as harmful use of alcohol and other substances are required as a means of supporting medication uptake and adherence, as well as reducing risk taking behaviours that have been shown to have further negative impact the health of those who are infected and may put others at risk. As an example, research should focus on understanding the paradoxical relationship between participants’ simultaneous willingness to use recreational drugs and reluctance to accept ART, especially when the former can be dangerous and the latter life-saving. Similarly, research should explore the perspectives of those who choose not to access ART, but choose instead CAM as a means of managing their health. These studies may provide insights valuable to understanding the determinants of decisions that extend beyond what is currently deemed rational in the realm of contemporary medicine. Furthermore, observational studies suggest a high prevalence of psychological, psychosocial and socioeconomic issues among PLHIV. It is also commonly reported that these issues have a negative impact on treatment uptake and adherence. What is lacking is research to determine how these variables interplay in the management of HIV.

Limitations

There are some limitations of this research and these are acknowledged. Firstly, only articles published in peer-reviewed journals were included in the review. It is possible that grey literature and unpublished works would offer further insights that may have enhanced understanding in this topic area. However, accessing these resources and attempting to validate the quality of such research would have been difficult and time consuming. Given that this review included quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods research, the regrettable exclusion of grey literature is justified. Secondly, quality assessment of the included studies utilised a relatively new tool that is largely untried. Furthermore, the tool assessed only the methodological quality and not the validity of study findings. However, the tool allowed a holistic approach to the quality appraisal process that promoted the utilisation of the researchers’ skills and judgement in assessing the value of the contribution of each article to the knowledge pool. It provided flexibility for the inclusion of research that may have been imperfectly executed, but still offered valuable insights important to understanding the perspectives of people who live with HIV. Finally, the review included studies published between 2000 and 2015, some of which reported on data collected prior to the year 2000 and may therefore, relate to aspects of care and medication that are no longer in common use or have changed significantly. However, these studies provided understanding of the perspectives of PLHIV that may have been neglected in more modern studies. Thus, the inclusion of the earlier research is justified, though its current applicability must be considered in this light.

Conclusion

This study highlights how people attach different meanings to being HIV positive and to their personal identity, the role of ART, CAM and other substances in their lives, as well as the role of social and cultural communities in which they are embedded. The study sheds light on the impact of living with HIV on decisions regarding disclosure, treatment uptake and adherence. While the study provides clues, more research is needed to understand how these meanings are generated and how they give rise to rationales regarding HIV management. In addition, a review of studies focused on testing and risk taking behaviour is required to provide a holistic overview of the barriers and facilitators to the effective management of HIV in the Australian context.

Notes

Medicare universal health insurance scheme refers to both the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and Medicare Benefits Schedule.

Treatment uptake refers to individuals decisions to access ART.

Treatment adherence refers to the individuals’ behaviour in taking ART at the dose, frequency, duration and in a manner as prescribed.

References

UNAIDS. How AIDS changed everything. MDG 6: 15 years, 15 lessons of hope from the AIDS response. UNAIDS. http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2015/MDG6_15years-15lessonsfromtheAIDSresponse. Accessed 19 Oct 2015.

WHO. HIV/AIDS Fact sheet. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs360/en/. Accessed 2 Oct 2015.

WHO. Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations. World Health Organization. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/128048/1/9789241507431_eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1. Accessed 2 Oct 2015.

WHO. Global update on the health sector response to HIV, 2014. World Health Organization. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/128494/1/9789241507585_eng.pdf. Accessed 12 Nov 2015.

UNAIDS. 90-90-90—An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. UNAIDS. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90-90-90_en_0.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct 2015.

Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. AIDSinfo. http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines. Accessed 2 Nov 2015.

Cadosch D, Bonhoeffer S, Kouyos R. Assessing the impact of adherence to anti-retroviral therapy on treatment failure and resistance evolution in HIV. J R Soc Interface. 2012;9(74):2309–20.

Fogarty L, Roter D, Larson S, Burke J, Gillespie J, Levy R. Patient adherence to HIV medication regimens: a review of published and abstract reports. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;46(2):93–108.

Nachega JB, Hislop M, Dowdy DW, Chaisson RE, Regensberg L, Maartens G. Adherence to nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based HIV therapy and virologic outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(8):564–73.

von Wyl V, Klimkait T, Yerly S, et al. Adherence as a predictor of the development of class-specific resistance mutations: the Swiss HIV cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e77691.

Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(1):21–30.

UNAIDS. The gap report. UNAIDS. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_Gap_report_en.pdf. Accessed 5 Nov 2015.

Gupta RK, Wainberg MA, Brun-Vezinet F, et al. Oral antiretroviral drugs as public health tools for HIV prevention: global implications for adherence, drug resistance, and the success of HIV treatment programs. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(Suppl 2):S101–6.

The Kirby Institute for Infection and Immunity in Society. HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmissible infections in Australia annual surveillance report 2015. UNSW Australia: The Kirby Institute. https://kirby.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/files/hiv/resources/ASR2015.pdf. Accessed 19 Oct 2015.

Australian Government Department of Health. Seventh National HIV Strategy 2014–2017. The Department of Health. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/ohp-bbvs-hiv. Accessed 10 Oct 2015.

AVERT. 2015 Global HIV and AIDS statistics. AVERT. AVERTing HIV and AIDS. http://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-around-world/global-statistics. Accessed 11 Nov 2015.

Australian Government Attorney-General’s Department. Human Rights and Anti-Discrimination Bill 2012: Exposure draft legislation. Australian Government Attorney-General’s Department. http://www.ag.gov.au/consultations/documents/consolidationofcommonwealthanti-discriminationlaws/human%20rights%20and%20anti-discrimination%20bill%202012%20-%20exposure%20draft%20.pdf. Accessed 9 Nov 9 2015.

National HIV Testing Policy Expert Reference Committee. 2011 National HIV Testing Policy v1.3 (November 2011). ASHM. http://testingportal.ashm.org.au/hiv/63-testing-policy/version-tracking/141-hiv-testing-policy-version-changes. Accessed 9 Nov 2015.

Grierson J, Pitts M, Koelmeyer RL. HIV Futures Seven: The health and wellbeing of HIV positive people in Australia. ACON. http://www.acon.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/HIV-Futures-7-report-2013.pdf. Accessed 9 Nov 2015.

Australian Government Department of Health. The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. PBS. http://www.pbs.gov.au/info/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2013-11/first-line-art. Accessed 3 Nov 2015.

de Wit J, Mao L, Treloar C. Annual report of trends in behaviour 2015. UNSW Australia: Centre for Social Research in Health. https://csrh.arts.unsw.edu.au/media/CSRHFile/CSRH_Annual_Report_of_Trends_in_Behaviour_2015.pdf. Accessed 1 Dec 1 2015.

Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Analysing qualitative data. Qualitative Research in Health Care. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2007. p. 63–81.

Mays N, Pope C. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ. 2000;320(7226):50–2.

Pace R, Pluye P, Bartlett G, et al. Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(1):47–53.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9.

Begley K, McLaws M, Ross MW, Gold J. Cognitive and behavioural correlates of non-adherence to HIV anti-retroviral therapy: theoretical and practical insight for clinical psychology and health psychology. Clin Psychol. 2008;12(1):9–17.

Brener L, Callander D, Slavin S, De Wit J. Experiences of HIV stigma: the role of visible symptoms, HIV centrality and community attachment for people living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2013;25(9):1166–73.

de Visser R, Ezzy D, Bartos M. Alternative or complementary? Nonallopathic therapies for HIV/AIDS. Altern Ther Health Med. 2000;6(5):44–52.

Edmiston N, Passmore E, Smith DJ, Petoumenos K. Multimorbidity among people with HIV in regional New South Wales, Australia. Sex Health. 2015;12(5):425–32.

Fong R, Cheng AC, Vujovic O, Hoy JF. Factors associated with virological failure in a cohort of combination antiretroviral therapy-treated patients managed at a tertiary referral centre. Sex Health. 2013;10(5):442–7.

Gibbie T, Hay M, Hutchison CW, Mijch A. Depression, social support and adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in people living with HIV/AIDS. Sex Health. 2007;4(4):227–32.

Gold RS, Hinchy J, Batrouney CG. The reasoning behind decisions not to take up antiretroviral therapy in Australians infected with HIV. Int J STD AIDS. 2000;11(6):361–70.

Grierson J, de Visser R, Bartos M. More cautious, more optimistic: Australian people living with HIV/AIDS, 1997-1999. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12(10):670–6.

Grierson JG, Misson SA, Pitts MK. Correlates of antiretroviral treatment breaks. HIV Med. 2004;5(1):34–9.

Grierson JW, Pitts MK, Misson S. Health and wellbeing of HIV-positive Australians: findings from the third national HIV Futures Survey. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16(12):802–6.

Guy R, Wand H, McManus H, et al. Antiretroviral treatment interruption and loss to follow-up in two HIV cohorts in Australia and Asia: implications for ‘test and treat’ prevention strategy. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27(12):681–91.

Herrmann S, McKinnon E, John M, et al. Evidence-based, multifactorial approach to addressing non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy and improving standards of care. Intern Med J. 2008;38(1):8–15.

Herrmann SE, McKinnon EJ, Williams LJ, et al. Use of alcohol, nicotine and other drugs in the Western Australian HIV Cohort study. Sex Health. 2012;9(2):199–201.

Hutton VE, Misajon R, Collins FE. Subjective wellbeing and ‘felt’ stigma when living with HIV. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(1):65–73.

McAllister J, Beardsworth G, Lavie E, MacRae K, Carr A. Financial stress is associated with reduced treatment adherence in HIV-infected adults in a resource-rich setting. HIV Med. 2013;14(2):120–4.

Pakenham KI, Rinaldis M. The role of illness, resources, appraisal, and coping strategies in adjustment to HIV/AIDS: the direct and buffering effects. Int J Behav Med. 2001;24(3):259–79.

Skevington SM, Norweg S, Standage M, Group WH. Predicting quality of life for people living with HIV: international evidence from seven cultures. AIDS Care. 2010;22(5):614–22.

Sternhell PS, Corr MJ. Psychiatric morbidity and adherence to antiretroviral medication in patients with HIV/AIDS. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2002;36(4):528–33.

Thorpe R, Grierson J, Pitts M. Gender differences in patterns of HIV service use in a national sample of HIV-positive Australians. AIDS Care. 2008;20(5):547–52.

Van De Ven P, Crawford J, Kippax S, Knox S, Prestage G. A scale of optimism-scepticism in the context of HIV treatments. AIDS Care. 2000;12(2):171–6.

Wilson KJ, Doxanakis A, Fairley CK. Predictors for non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Sex Health. 2004;1(4):251–7.

Bartos M. HIV as identity, experience or career. AIDS Care. 2000;12(3):299–306.

Jenkin P, Koch T, Kralik D. The experience of fatigue for adults living with HIV. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15(9):1123–31.

McDonald K, Slavin S. My body, my life, my choice: practices and meanings of complementary and alternative medicine among a sample of Australian people living with HIV/AIDS and their practitioners. AIDS Care. 2010;22(10):1229–35.

McDonald K, Slavin S, Pitts MK, Elliott JH, Team HP. Chronic disease self-management by people with HIV. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(6):863–70.

Newman CE, Mao L, Persson A, et al. ‘Not until I’m absolutely half-dead and have to:’ accounting for non-use of antiretroviral therapy in semi-structured interviews with people living with HIV in Australia. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29(5):267–78.

Paxton S. The paradox of public HIV disclosure. AIDS Care. 2002;14(4):559–67.

Thorpe RD. Integrating biomedical and CAM approaches: the experiences of people living with HIV/AIDS. Health Sociol Rev. 2008;17(4):410–8.

Thorpe RD. ‘Doing’ chronic illness? Complementary medicine use among people living with HIV/AIDS in Australia. Sociol Health Illn. 2009;31(3):375–89.

Tsarenko Y, Polonsky MJ. ‘You can spend your life dying or you can spend your life living’: identity transition in people who are HIV-positive. Psychol Health. 2011;26(4):465–83.

Ezzy D. Illness narratives: time, hope and HIV. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(5):605–17.

Goode M, McMaugh A, Crisp J, Wales S, Ziegler JB. Adherence issues in children and adolescents receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Care. 2003;15(3):403–8.

McDonald K, Bartos M, Rosenthal D. Australian women living with HIV/AIDS are more sceptical than men about antiretroviral treatment. AIDS Care. 2001;13(1):15–26.

Thomas S, Lam K, Piterman L, Mijch A, Komesaroff P. Complementary medicine use among people living with HIV/AIDS in Victoria, Australia: practices, attitudes and perceptions. Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18(7):453–7.

Fairley CK, Levy R, Rayner CR, et al. Randomized trial of an adherence programme for clients with HIV. Int J STD AIDS. 2003;14(12):805–9.

Grierson JW, Pitts MK, Thorpe RD. State of the (positive) nation: findings from the fourth national Australian HIV futures survey. Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18(9):622–5.

Grierson J, Koelmeyer RL, Smith A, Pitts M. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy: factors independently associated with reported difficulty taking antiretroviral therapy in a national sample of HIV-positive Australians. HIV Med. 2011;12(9):562–9.

Broom J, Sowden D, Williams M, Taing K, Morwood K, McGill K. Moving from viral suppression to comprehensive patient-centered care: the high prevalence of comorbid conditions and health risk factors in HIV-1-infected patients in Australia. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care. 2012;11(2):109–14.

Kelly A. Living loss: an exploration of the internal space of liminality. Mortality. 2008;13(4):335–50.

Levy R, Rayner C, Fairley C, et al. Multidisciplinary HIV adherence intervention: a randomized study. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2004;18(12):728–35.

Willis J. Panic at the discourse: Episodes from an analytic autoethnography about living with HIV. Illn Crises Loss. 2011;19(3):259–75.

Chow MY, Li M, Quine S. Client satisfaction and unmet needs assessment: evaluation of an HIV ambulatory health care facility in Sydney, Australia. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2012;24(2):406–14.

de Visser R, Grierson J. Use of alternative therapies by people living with HIV/AIDS in Australia. AIDS Care. 2002;14(5):599–606.

Newman CE, de Wit J, Persson A, et al. Understanding concerns about treatment-as-prevention among people with HIV who are not using antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(5):821–31.

International Collaboration on HIV Optimism. HIV treatments optimism among gay men: an international perspective. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32(5):545–50.

Knox S, Van De Ven P, Prestage G, Crawford J, Grulich A, Kippax S. Increasing realism among gay men in Sydney about HIV treatments: changes in attitudes over time. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12(5):310–4.

Koelmeyer R, English DR, Smith A, Grierson J. Association of social determinants of health with self-rated health among Australian gay and bisexual men living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2014;26(1):65–74.

Zablotska I, Frankland A, Imrie J, et al. Current issues in care and support for HIV-positive gay men in Sydney. Int J STD AIDS. 2009;20(9):628–33.

Gold RS, Ridge DT. “I will start treatment when I think the time is right”: HIV-positive gay men talk about their decision not to access antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Care. 2001;13(6):693–708.

Holt M, Stephenson N. Living with HIV and negotiating psychological discourse. Health. 2006;10(2):211–31.

Holt M. Gay men and ambivalence about ‘gay community’: from gay community attachment to personal communities. Cult Health Sex. 2011;13(8):857–71.

Persson A, Race K, Wakeford E. HIV health in context: negotiating medical technology and lived experience. Health. 2003;7(4):397–415.

Persson A. Facing HIV: body shape change and the (in)visibility of illness. Med Anthropol. 2005;24(3):237–64.

Holt M, Murphy D, Callander D, et al. HIV-negative and HIV-positive gay men’s attitudes to medicines, HIV treatments and antiretroviral-based prevention. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(6):2156–61.

Down I, Prestage G, Triffitt K, Brown G, Bradley J, Ellard J. Recently diagnosed gay men talk about HIV treatment decisions. Sex Health. 2014;11(2):200–6.

Murray JM, Prestage G, Grierson J, Middleton M, McDonald A. Increasing HIV diagnoses in Australia among men who have sex with men correlated with the growing number not taking antiretroviral therapy. Sex Health. 2011;8(3):304–10.

Munro I, Edward KL. The burden of care of gay male carers caring for men living with HIV/AIDS. Am J Mens Health. 2010;4(4):287–96.

Newman CE, Bonar M, Greville HS, Thompson SC, Bessarab D, Kippax SC. Barriers and incentives to HIV treatment uptake among Aboriginal people in Western Australia. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 1):S13–7.

Newman CE, Bonar M, Greville H, Thompson SC, Bessarab D, Kippax SC. ‘Everything is okay’: the influence of neoliberal discourse on the reported experiences of Aboriginal people in Western Australia who are HIV-positive. Cult Health Sex. 2007;9(6):571–84.

Thompson SC, Bonar M, Greville H, et al. “Slowed right down”: insights into the use of alcohol from research with Aboriginal Australians living with HIV. Int J Drug Policy. 2009;20(2):101–10.

Herrmann S, Wardrop J, John M, et al. The impact of visa status and Medicare eligibility on people diagnosed with HIV in Western Australia: a qualitative report. Sex Health. 2012;9(5):407–13.

Korner H. ‘If I had my residency I wouldn’t worry’: negotiating migration and HIV in Sydney, Australia. Ethn Health. 2007;12(3):205–25.

Woolley I, Bialy C. Visiting friends and relatives may be a risk for non-adherence for HIV-positive travellers. Int J STD AIDS. 2012;23(11):833–4.

Ayton DR, Guy RJ, Woolley IJ, Hellard ME. Cambodian-born individuals diagnosed with HIV in Victoria: epidemiological findings and health service implications. Sex Health. 2007;4(3):209.

Korner H. Late HIV diagnosis of people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds in Sydney: the role of culture and community. AIDS Care. 2007;19(2):168–78.

Korner H. Negotiating cultures: disclosure of HIV-positive status among people from minority ethnic communities in Sydney. Cult Health Sex. 2007;9(2):137–52.

Giles ML, Hellard ME, Lewin SR, O’Brien ML. The work of women when considering and using interventions to reduce mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of HIV. AIDS Care. 2009;21(10):1230–7.

McDonald K, Kirkman M. HIV-positive women in Australia explain their use and non-use of antiretroviral therapy in preventing mother-to-child transmission. AIDS Care. 2011;23(5):578–84.

Persson A, Richards W. From closet to heterotopia: a conceptual exploration of disclosure and ‘passing’ among heterosexuals living with HIV. Cult Health Sex. 2008;10(1):73–86.

Persson A. Reflections on the Swiss Consensus Statement in the context of qualitative interviews with heterosexuals living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2010;22(12):1487–92.

Persson A. “I don’t blame that guy that gave it to me”: contested discourses of victimisation and culpability in the narratives of heterosexual women infected with HIV. AIDS Care. 2014;26(2):233–9.

Cummins D, Millar KH. Experiences of HIV-positive women in Sydney. Australia. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2004;15(3):70–4.

Giles ML, McDonald AM, Elliott EJ, et al. Variable uptake of recommended interventions to reduce mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Australia, 1982–2005. Med J Aust. 2008;189(3):151–4.

Lemoh CN, Baho S, Grierson J, Hellard M, Street A, Biggs BA. African Australians living with HIV: a case series from Victoria. Sex Health. 2010;7(2):142–8.

Persson A. The undoing and doing of sexual identity among heterosexual men with HIV in Australia. Men Masc. 2012;15(3):311–28.

Korner H, Hendry O, Kippax S. Safe sex after post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV: intentions, challenges and ambivalences in narratives of gay men. AIDS Care. 2006;18(8):879–87.

Australian Government Department of Health. Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) New options for HIV patient access. Australian Government Department of Health. http://www.pbs.gov.au/general/changes-to-certain-s100-programs/faqs-hsd-ca-hiv-hbv-19-june-2015.pdf. Accessed 15 Oct 2015.

ENDINGHIV.ORG.AU. PREP. A once a day pill that keeps you HIV negative. ENDINGHIV.ORG.AU. http://endinghiv.org.au/nsw/stay-safe/prep/. Accessed December 05 2015.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank HIV Foundation Queensland for providing financial assistance and Griffith University for providing administrative support. Administrative and financial assistance must not be taken as endorsement of the contents of this report.

Funding

This study was funded by the HIV Foundation Queensland (Yes to recreational drugs but no to life saving medications: Unpacking paradoxical attitudes about treatments to improve medication adherence).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare there are no existing or potential conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mey, A., Plummer, D., Dukie, S. et al. Motivations and Barriers to Treatment Uptake and Adherence Among People Living with HIV in Australia: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. AIDS Behav 21, 352–385 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1598-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1598-0