Abstract

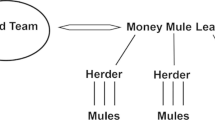

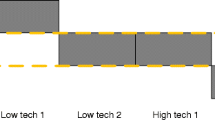

Two recent studies which are part of the Dutch Research Program on the Safety and Security of Online Banking, present empirical material regarding the origin, growth and criminal capabilities of cybercriminal networks carrying out attacks on customers of financial institutions. This article extrapolates upon the analysis of Dutch cases and complements the existing picture by providing insight into 22 cybercriminal networks active in Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States. The analysis regarding origin and growth shows that social ties play an important role in the majority of networks. These networks usually originate and grow either by means of social contacts alone or by the combined use of social contacts and forums (to recruit specialists). Equally, however, forums play a vital role within the majority of the networks by offering a place where co-offenders can meet, recruit and trade criminal ‘services’. Moreover, those networks where origin and growth is primarily based on forums appear capable of creating more flexible forms of cooperation between key members and enablers, thereby facilitating a limited number of core members to become international players. Analysis of the capabilities of criminal networks shows that all networks are primarily targeted towards customers of financial institutions, but most networks are not restricted to one type of crime. Core members are often involved in other forms of offline and online crime. The majority of networks fall into the high-tech category of networks, mostly international, high-tech networks. These are networks with core members, enablers, and victims originating from different countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Phishing is the process whereby criminals use digital means such as e-mail to try to retrieve users’ personal information by posing as a trusted authority (see, for example, [12]). The criminal may send an e-mail that appears to originate from a trusted party such as a bank. This e-mail refers to a problem with the user’s online bank account (such as the need for a security upgrade), combined with a request for the user to take immediate action to resolve the issue (for example, by logging in using the link in the e-mail to update the account security). The aim of the attack is to intercept user credentials. These can also, however, be intercepted in a more technological way as criminals can use ‘malware’ (malicious software) such as viruses, worms, Trojan horses and spyware to obtain access to credentials or manipulate entire online banking sessions.

References

Décary-Hétu, D., & Dupont, B. (2012). The social network of hackers. Global Crime, 13(3), 160–175.

Dupont, B., Côté, A., Savine, C., & Décary-Hétu, D. (2016). The ecology of trust among hackers. Global Crime, 17(2), 129–151.

Holt, J. T., & Lampke, E. (2009). Exploring stolen data markets online: Products and market forces. Criminal Justice Studies, 23(1), 33–50.

Leukfeldt, E. R., Kleemans, E. R., & Stol, W. P. (2016a). Cybercriminal networks, social ties and online forums. Social ties versus digital ties within phishing and malware networks. British Journal of Criminology. doi:10.1093/bjc/azw009.

Leukfeldt, E.R., Kleemans, E.R., & Stol, W.P. (2016b). A typology of cybercriminal networks: From low tech locals to high tech specialists. Crime, Law and Social Change. doi:10.1007/s10611-016-9646-2.

Lu, Y., Luo, X., Polgar, M., & Cao, Y. (2010). Social network analysis of a criminal hacker community. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 51(2), 31–41.

Peretti, K. K. (2008). Data breaches: what the underground world of “carding” reveals. Santa Clara Computer and High Technology Law Journal, 25(2), 345–414.

Soudijn, M. R. J., & Zegers, B. C. H. T. (2012). Cybercrime and virtual offender convergence settings. Trends in Organized Crime, 15(2), 111–129.

Yip, M., Shadbolt, N., & Webber, C. (2012). Structural Analysis of Online Criminal Social Networks. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Intelligence and Security Informatics (ISI) 2012, 60–65. June 11–14, 2012, Washington.

Kleemans, E. R., van de Bunt, H. G., & van den Berg, E. A. I. M. (1998). Georganiseerde criminaliteit in Nederland. Rapportage op basis van de WODC Monitor [Organized Crime in the Netherlands]. The Hague: Ministry of Justice / WODC.

Kruisbergen, E. W., van de Bunt, H. G., & Kleemans, E. R. (2012). Georganiseerde criminaliteit in Nederland. Vierde rapportage op basis van de Monitor Georganiseerde Criminaliteit [Organized Crime in the Netherlands]. The Hague: WODC.

Lastdrager, E. E. H. (2014). Achieving a consensual definition of phishing based on a systematic review of the literature. Crime Science, 3(9), 1–6.

Leukfeldt, E. R. (2014). Cybercrime and social ties. Phishing in Amsterdam. Trends in Organized Crime, 17(4), 231–249.

Kleemans, E. R. (2014). Organized crime research: Challenging assumptions and informing policy. In J. Knutsson & E. Cockbain (Eds.), Applied police research: challenges and opportunities. Crime science series. Cullompton: Willan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1: Analytical framework

Appendix 1: Analytical framework

Direct ties

-

Describe the composition of the criminal network: how are the suspects related, their role and/or function within the network (subgroups, core functions, facilitators, periphery).

-

Describe the structure of the criminal network (standalone unit, fluid cooperation based on a specific goal).

-

Is there a hierarchy and / or mutual dependency?

Origin and growth

-

How, when and where did the criminal cooperation start?

-

Do the suspects have a common background? (Family, neighborhood, friends, occupation, place of origin, etc.). If not, in what way are the suspects related and how did the cooperation start?

-

What kept the members of the criminal network together? (e.g. social ties, economic advantages, fear, etc.).

-

Describe the period/duration of the activities.

-

Describe changes within the composition of the criminal network.

-

How are new members being recruited?

Offender convergence settings

-

Describe the (digital) offender convergence setting used by the criminals.

Modus operandi

-

Describe the main criminal activities of the network (describe the MO in detail in the next section)

-

Describe secondary criminal activities of the network and individual offenders.

-

What is the working area of the network (region, country, interaction, certain banks).

-

Who are the suitable targets for this network? (which type of people are attacked).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leukfeldt, E.R., Kleemans, E.R. & Stol, W.P. Origin, growth and criminal capabilities of cybercriminal networks. An international empirical analysis. Crime Law Soc Change 67, 39–53 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-016-9663-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-016-9663-1