Abstract

The aim of this paper is to infer the spatial extent of agglomeration economies for the creative service industries (CSI) in Barcelona and its relationship with firm performance controlling for urban characteristics and demand factors. Using micro-geographic data from the mercantile register for firms between 2006 and 2015, I estimated the effect of intra-industry and inter-industry agglomeration in rings around location on productivity in Barcelona. The main results are: (1) for CSI, at a micro-spatial level, localisation economies are important within the first 250 m; (2) for non-CSI, having employees in the CSI in close proximity (250–500 m) enhances their productivity; (3) for symbolic-based CSI firms, localisation economies—mainly understood as networking and/or knowledge externalities—have positive effects on TFP at shorter distances (less than 500 m), while for the two other knowledge-based CSI (i.e. synthetic and analytical) localisation economies seem not to be so important; and (4) market potential does not offset localisation economies for CSI. These results strongly suggest the importance of agglomeration externalities in CSI, which are strongly concentrated in the largest cities.

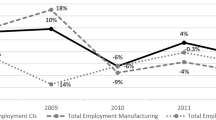

Source: Own elaboration

Source: Own elaboration with OSM, Barcelona Council and SABI’s data

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Creative industries are defined as knowledge-based activities based on individual creativity, skill and talent, with the potential for wealth and job creation through the development of intellectual property (UNCTAD 2010). See DCMS (2001, 2013), European Commission (2010, 2016) and UNCTAD (2008, 2010, 2015) reports to understand the increasing relevance of these industries over the last decade.

Creative industries represent 10.5% of all the firms in the city of Barcelona. In terms of labour market, Barcelona accounts for the 49% of the total employment in creative industries in Catalonia.

Creative service industries (CSI) are those creative industries operating in the service sector. They include industries like arts, advertising, cinema, design, publishing, radio and TV, R&D or software (UNCTAD 2010). This paper focuses on CSI for two main reasons: (i) more than 90% of all creative industries firms in Barcelona operate in the service sector (Ajuntament de Barcelona 2015) and (ii) networking, knowledge spillovers, market potential and urban amenities effects on firms productivity are expected to be more intense for CSI than for creative manufacturing (Coll-Martínez et al. 2018). See Sect. 3 for further details.

See Sect. 3 for a definition of the different knowledge bases and a classification of CSI according to their dominant knowledge base.

The MAUP appears when the same analysis is applied to the same data, but different spatial aggregation schemes are used, which give different results. MAUP takes two forms: the scale effect and the zone effect. The scale effect gives different results when the same analysis is applied to the same data, but changes the scale of the aggregation units. The zone effect is observed when the scale of analysis is fixed, but the shape of the aggregation units is changed. See Arbia (2001) for more details.

Given that some authors strongly recommend comparing different approaches before choosing among them (Combes and Gobillon 2015), TFP is also estimated by following Levinsohn and Petrin (2003) and by using OLS. Still, as results do not seem to vary significantly, TFP results are presented according to Ackerberg et al. (2015).

Here, Ait is a variable that contains the estimated TFP coefficient for each of the firms in the panel.

Fu (2007) also makes use of local fixed effects to estimate the attenuation of agglomeration economies on wages.

In the literature, several studies use this database (Duch et al. 2009; Jofre-Monseny and Solé-Ollé 2009 or Jofre-Monseny et al. 2015) and some of them have explored its representativeness by computing the correlation between SABI and the Social Security Register and finding a high correlation of around 0.90 (Jofre-Monseny et al. 2014). We can find also papers in the creative industries literature that use this database. See, for instance, Camelo-Ordaz et al. (2011), Bertacchini and Borrione (2013), Boix-Domenech et al. (2015), Sánchez-Serra (2016) or Coll-Martínez et al. (2018).

Creative industries arose out of cultural activities. The term came to the fore after the publication of reports by the OECD (2007) and UNCTAD (2010) and the British Government’s Creative Industries Task Force Mapping Document (DCMS 2001). All of them are well accepted in the literature as alternative classifications.

It is worth noting that the attribution of a NACE code to a single dominant knowledge base is obviously a simplification to facilitate the analysis. In fact, workers employed in each creative sector carry out several job functions that usually depend on a mix of different knowledge bases (Asheim and Hansen 2009).

Non-CSI refers to all firms in SABI database unless those belonging to CSI in the service sectors.

Alternative proxies for potential demand have been drawn up and tested in the same model as a robustness check, specifically distance to different hotspots in the city (economic activity, face-to-face interaction, nightlife, tourism, events, etc.). However, these variables are usually correlated with localisation and urbanisation firm ring variables and when they are used, and results slightly vary.

Alternatively, neighbourhood, sector and trend fixed effects were added as robustness checks. However, as they are considerably correlated with localisation and urbanisation firm ring variables, they were finally discarded. See Sect. 4.2 for further details.

I refrain to interpret the intra-industry ring firm variables for non-CSI as localisation economies due to the diversity of activities included in each of them. Instead of localisation economies, they should be understood as a broad measure of agglomeration economies. Still, the creation of non-CSI variables allows to understand the effects of economies of diversity for CSI.

They find that one unit increase in the number of neighbours in the first ring (up to 250 m) leads to a 2% increase in the expected number of advertising agency births. Although Arzaghi and Henderson (2008) focus on advertising agencies in Manhattan and their empirical model is based on firm entries instead of TFP, this result is not further from that of the present paper (0.99%).

Alternatively, this result may be explained by the fact that urbanisation economies may be capturing the advantages of the buzz and diversity of economic activities and people as population density may do. Even so, urbanisation economies coefficients were not affected when population density is not added to the model. Systematic empirical support for that argument in the context of CSI is left for future research.

While Arzaghi and Henderson (2008) apply count data models to understand firm location decisions as a proxy of expected returns and productivity, the present paper estimates agglomeration externalities effects on CSI firm TFP.

Hausman’s (1978) specification test compares an estimator \(\widehat{{\theta_{1} }}\) that is known to be consistent with an estimator \(\widehat{{\theta_{1} }}\) that is efficient under the assumption being tested. The null hypothesis is that the estimator \(\widehat{{\theta_{1} }}\) is indeed an efficient (and consistent) estimator of the true parameters. If this is the case, there should be no systematic difference between the two estimators. If there exists a systematic difference in the estimates, we have reason to doubt the assumptions on which the efficient estimator is based.

Results are available upon request.

References

Ackerberg, D. A., Caves, K., & Frazer, G. (2015). Identification properties of recent production function estimators. Econometrica, 83, 2411–2451.

Ajuntament de Barcelona. (2015). Barcelona en xifres 2015. Principals indicadors econòmics de l’àrea de Barcelona. Barcelona Activa. https://www.slideshare.net/barcelonactiva/barcelona-en-xifres-2015.

Ajuntament de Barcelona. (2018). Fàbriques de creació de Barcelona. https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/fabriquescreacio

Andersson, Å. E., Andersson, D. E., Daghbashyan, Z., & Hårsman, B. (2014). Location and spatial clustering of artists. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 47, 128–137.

Arbia, G. (1989). Spatial data configuration in statistical analysis of regional economic and related problems. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Arbia, G. (2001). Modeling the geography of economic activities on a continuous space. Papers in Regional Science, 80, 411–424.

Arzaghi, M., & Henderson, J. V. (2008). Networking off madison avenue. Review Economic Studies, 75, 1011–1038.

Asheim, B., Coenen, L., & Vang, J. (2007). Face-to-face, buzz and knowledge bases: Socio-spatial implications for learning, innovation and innovation policy. Environment and Planning C, 25, 655–670.

Asheim, B., & Hansen, H. K. (2009). Knowledge bases, talents, and contexts: On the usefulness of the creative class approach in Sweden. Economic Geography, 85, 425–442.

Asheim, B. R., & Parrilli, M. D. (2012). Introduction: Learning and interaction—drivers for innovation in current competitive markets. In B. T. Asheim & M. D. Parrilli (Eds.), Interactive learning for innovation: A fey driver within clusters and innovation systems. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Backman, M., & Nilsson, P. (2018). The role of cultural heritage in attracting skilled individuals. Journal of Cultural Economics, 42, 111–138.

Banks, M., Lovatte, A., O’Connor, J., & Raffo, C. (2000). Risk and trust in the cultural industries. Geoforum, 31, 453–464.

Bertacchini, E. E., & Borrione, P. (2013). The geography of the italian creative economy: The special role of the design and craft-based industries. Regional Studies, 47, 135–147.

Boix-Domenech, R., Hervás-oliver, J. L., & De Miguel-Molina, B. (2015). Micro-geographies of creative industries clusters in Europe: From hot spots to assemblages. Papers in Regional Science, 94(4), 753–772.

Boix-Domenech, R., & Soler-Marco, V. (2017). Creative service industries and regional productivity. Papers in Regional Science, 96(2), 261–279.

Branzanti, C. (2014). Creative clusters and district economies: Towards a taxonomy to interpret the phenomenon. European Planning Studies, 23, 1401–1418.

Camelo-Ordaz, C., Fernandez-Alles, M., Ruiz-Navarro, J., & Sousa-Ginel, E. (2011). The intrapreneur and innovation in creative firms. International Small Business Journal, 30, 513–535.

Caves, R. (2000). Creative industries: Contracts between art and commerce. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Cerisola, S. (2018a). Multiple creative talents and their determinants at the local level. Journal of Cultural Economics, 42, 243–269.

Cerisola, S. (2018b). A new perspective on the cultural heritage–development nexus: The role of creativity. Journal of Cultural Economics, 20, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-018-9328-2.

Ciccone, A., & Hall, R. E. (1996). Productivity and the density of economic activity. American Economic Review, 86, 54–70.

Coll-Martínez, E., & Arauzo-Carod, J. M. (2017). Creative milieu and firm location: An empirical appraisal. Environment and Planning A, 49, 1613–1641.

Coll-Martínez, E., Moreno-Monroy, A. I., & Arauzo-Carod, J. M. (2018). Agglomeration of creative industries: An intra-metropolitan analysis for Barcelona. Papers in Regional Science, https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12330.

Combes, P. P., & Gobillon, L. (2015). The empirics of agglomeration economies. In E. G. Duranton, V. Henderson, W. Strange, & P. Combes (Eds.), Handbook of urban and regional economics. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Commission, European. (2010). Green paper—Unlocking the potential of cultural and creative industries. Luxemburg: European Commission.

Commission, European. (2016). Boosting the competitiveness of cultural and creative industries for growth and jobs. Luxemburg: Austrian Institute for SME Research and VVA Europe.

Cooke, P. N., & Lazzeretti, I. (2008). Creative cities, cultural clusters and local economic development. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Currid, E., & Williams, S. (2010). Two cities, five industries: Similarities and differences within and between Cultural Industries in New York and Los Angeles. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 29, 322–335.

DCMS. (2001). The creative industries mapping document 2001. London: DCMS.

DCMS. (2013). Classifying and measuring the creative industries. London: DCMS.

De Jong, J. P. J., Fris, P., & Stam, E. (2007). Creative industries–heterogeneity and connection with regional firm entry. Zoetermeer: EIM Business and Policy Research.

De Propris, L., Chapain, C., Cooke, P., & Macneill, S. (2009). The geography of creativity. London: Nesta.

Desmet, K., & Fafchamps, M. (2005). Changes in the spatial concentration of employment across US counties: A sectoral analysis 1972–2000. Journal of Economic Geography, 5, 261–284.

Di Addario, S., & Patacchini, E. (2008). Wages and the City. Evidence from Italy. Labour Economics, 15, 1040–1061.

Duch, N., Montolio, D., & Mediavilla, M. (2009). Evaluating the impact of public subsidies on a firm’s performance: A quasi-experimental approach. Investigaciones Regionales, 16, 143–165.

Falck, O., Fritsch, M., Heblich, S., & Otto, A. (2018). Music in the air: Estimating the social return to cultural amenities. Journal of Cultural Economics, 42, 365–391.

Florida, R. (2002). The rise of the creative class. New York: Basic Books.

Foord, J. (2009). Strategies for creative industries: An international review. Creative Industries Journal, 1(2), 91–113.

Fu, S. (2007). Smart Café cities: Testing human capital externalities in the Boston metropolitan area. Journal of Urban Economics, 61, 86–111.

Glaeser, E. L., Kolko, J., & Saiz, A. (2001). Consumer city. Journal of Economic Geography, 1(1), 27–50.

Hausman, J. A. (1978). Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica, 46, 1251–1271.

Henderson, J. V. (2003). Marshall’s scale economies. Journal of Urban Economics, 53, 1–28.

Henderson, J. V. (2007). Understanding knowledge spillovers. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 37, 497–508.

Hsiao, C. (2014). Analysis of panel data. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

IDESCAT. (2011). Indicadors 2011. Barcelona: IDESCAT.

IERMB. (2013). Informe Barcelona Metròpoli Creativa 2013. Economia del coneixement i economia creativa a Barcelona. Document de Síntesi. Ajuntament de Barcelona. http://barcelonadadescultura.bcn.cat/informe-barcelona-metropoli-creativa-2013/.

Jacobs, J. (1961). The death and life of great American cities. New York: Random House.

Jacobs, J. (1969). The economy of cities. London: Johnatan Cape.

Jofre-Monseny, J., Marín-López, R., & Viladecans-Marsal, E. (2014). The determinants of localization and urbanization economies: Evidence from the location of new firms in Spain. Journal of Regional Science, 54(2), 313–337.

Jofre-Monseny, J., Marín-López, R., & Viladecans-Marsal, E. (2015). The mechanisms of agglomeration: Evidence from the effect of inter-industry relations on the location of new firms. Journal of Urban Economics, 70, 61–74.

Jofre-Monseny, J., & Solé-Ollé, A. (2009). Tax differentials in intraregional firm location: Evidence from new manufacturing establishments in Spanish municipalities. Regional Studies, 44(6), 663–677.

Landry, C. (2000). The creative city: A toolkit for urban innovators. London: Earthscan Publications Ltd.

Lazzeretti, L., Capone, F., & Boix-Domenech, R. (2012). Reasons for clustering of creative industries in Italy and Spain. European Planning Studies, 20(8), 1243–1262.

Lee, S. Y., Florida, R., & Acs, Z. J. (2004). Creativity and entrepreneurship: A regional analysis of new firm formation. Regional Studies, 38, 879–891.

Levinsohn, J., & Petrin, A. (2003). Estimating production inputs to functions using control for unobservables. Review of Economic Studies, 70, 317–341.

Lorenzen, M., & Frederiksen, L. (2008). Why do cultural industries cluster? Localization, urbanization, products and projects. In P. N. Cooke & L. Lazzeretti (Eds.), Creative cities, cultural clusters and local economic development (pp. 155–179). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Manjón, M., & Mañez, J. (2016). Production function estimation in Stata using the Ackerberg–Caves–Frazer method. Stata Journal, 10(3), 288–308.

Mariotti, I., Pacchi, C., & Di Vita, S. (2017). Co-working spaces in Milan: Location patterns and urban effects. Journal of Urban Technology, 24, 47–66.

Marshall, A. (1920). Principles of economics. London: MacMillan.

Martin, F., Mayer, T., & Mayneris, F. (2011). Spatial concentration and plant-level productivity in France. Journal of Urban Economics, 69, 182–195.

Maskell, P., & Lorenzen, M. (2004). The cluster as market organisation. Urban Studies, 41(5–6), 991–1009.

Moriset, B. (2014). Building new places of the creative economy. The rise of coworking spaces. Paper presented at the 2nd geography of innovation international conference (Utrecht, January 2014).

OECD. (2007). Competitive cities. A new entrepreneurial paradigm in spatial development. Paris: OECD.

Olley, G. S., & Pakes, A. (1996). The dynamics of productivity in the telecommunications equipment industry. Econometrica, 64, 1263–1297.

Pareja-Eastaway, M. (2016). Creative industries. Journal of Evolutionary Studies in Business, 1(1), 38–50.

Pareja-Eastaway, M., & Pradel-i-Miquel, M. (2014). Towards the creative and knowledge economies: Analysing diverse pathways in Spanish cities. European Planning Studies, 23(12), 2404–2422.

Parrino, L. (2015). Coworking: Assessing the role of proximity in knowledge exchange. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 13, 261–271.

Rosenthal, S. S., & Strange, W. C. (2003). Geography, industrial organization, and agglomeration. Review of Economics and Statistics, 85, 377–393.

Rosenthal, S.S. & Strange, W.C. (2005). The geography of entrepreneurship in the New York Metropolitan area. Economic Policy Review, 11, 29–54. Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Rosenthal, S. S., & Strange, W. C. (2008). The attenuation of human capital spillovers. Journal of Urban Economics, 64, 373–389.

Sánchez-Serra, D. (2016). Determinants of the concentration of creative industries in Europe: Acomparison between Spain, Italy, France United Kingdom and Portugal. Doctoral Dissertation in Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Cerdanyola.

Santagata, W., & Bertacchini, E. (2011). Creative atmosphere: Cultural industries and local development. Working Paper Departament of Economics S. Cognetti de Martins, University of Turin, Paper Nº. 4.

Scott, A. J. (1997). The cultural economy of cities. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 21, 323–339.

Scott, A. J. (2006). Entrepreneurship, innovation and industrial development: Geography and the creative field revisited. Small Business Economics, 26(1), 1–24.

Scott, A. J., Agnew, J., Soja, E., & Storper, M. (2001). Global city-regions. In global city-regions: Trends, theory, policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tschang, F. T., & Vang, J. (2008). Explaining the spatial organization of creative industries: the case of the US. Videogames industry. Paper to be presented at the 25th celebration conference 2008 on entrepreneurship and innovation–organizations, institutions, systems and regions, June 17–20, 2008, Copenhagen, CBS, Denmark

UNCTAD. (2008). Creative economy. Report 2008. UNCTAD, Geneva.

UNCTAD. (2010). Creative economy. Report 2010. UNCTAD, Geneva.

UNCTAD. (2015). Creative economy outlook and country profiles: Trends in international trade in creative industries. Geneva: UNCTAD.

Van Beveren, I. (2012). Total factor productivity estimation: A practical review. Journal of Economic Surveys, 26, 98–128.

Acknowledgements

This paper was partially funded by ECO2013-42310-R, ECO2014-55553-P, the “Xarxa de Referència d’R+D+I en Economia i Polítiques Públiques,” the SGR programme (2014-SGR-299) of the Catalan Government, the “Departament d’Universitats, Recerca i Societat de la Informació de la Generalitat de Catalunya” and the “Fundación SGAE.” I would like to acknowledge research assistance by M. Lleixà and D. Siles, the helpful and supportive comments of J.M. Arauzo, M. Manjón and A. Moreno and the participants at the 5th Workshop in Industrial and Public Economics, the 19th INFER Annual Conference, the 2017 Edition of the Summer School in Urban Economics, the 57th ERSA Congress, the AQR Lunch Seminar (UB), the XLIII Reunión de Estudios Regionales and the Geoinno 2018. I also would like to thank two anonymous referees by their valuable comments. Any errors are, of course, my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Coll-Martínez, E. Creativity and the city: testing the attenuation of agglomeration economies in Barcelona. J Cult Econ 43, 365–395 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-019-09340-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-019-09340-9