Abstract

The main goal was the analysis of parameters describing the structure of the pore space of carbonate rocks, based on tomographic images. The results of CT images interpretation, made for 17 samples of Paleozoic carbonate rocks were shown. The qualitative and quantitative analysis of a pore system was performed. Objects were clustered according to the pore size. Within the clusters, the geometry parameters were analysed. The following dependences were obtained for carbonate rocks, also for individual clusters (due to the volume): (1) a linear relationship (on a bilogarithmic scale) between the specific surface and the Feret diameter and (2) a strong linear relationship between specific surface area and Feret diameter and average diameter of the objects calculated for the sphere. The results were then combined with available results from standard laboratory tests, including NMR and MICP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hydrocarbons trapped in carbonate rocks (limestone and dolomite) account for approximately 50% of oil and gas production around the world. Carbonate Paleozoic deposits are found in the interest of geologists and geophysicists due to possible hydrocarbon accumulation (Jaworowski and Mikołajewski 2007). Petrophysical properties of Paleozoic rocks are the target of investigation especially in the face of new research techniques and measuring capabilities (Akbar et al. 1995). Reservoirs in carbonate rocks are multiple-porosity and present significant petrophysical heterogeneity in the reservoir scale. That is the main reason of huge petrophysical heterogeneity to the reservoirs (Mazzullo and Chilingarian 1992). The distribution and volume of pores exert strong control on the production and stimulation characteristics of carbonate reservoirs (Wardlaw 1996).

New technologies in laboratory researches together with well-known conventional laboratory techniques on rocks were the basis of detailed rock analysis. Nano-CT (nano-computed X-ray tomography) with high image resolution is one of the novel techniques, which can be used for evaluation of key reservoir parameters in tight formations (Arns et al. 2005; Wennberg et al. 2009; Dohnalik 2013; Exner et al. 2015; Teles et al. 2016). Standard quantitative interpretation algorithms of CT (computed X-ray tomography) image analysis linked to petrophysical information were used in the paper. On this basis, a unique information on the low porosity and low permeability carbonates was obtained (Krakowska and Puskarczyk 2015; Krakowska et al. 2017).

We focused on non-classical carbonate reservoir rocks. As a research material, carbonate formations with low porosity and low permeability were chosen. This type of carbonates is much more difficult to interpret using standard techniques (Wei et al. 2017).

In this paper, we describe research material based on the standard laboratory results, e.g. density, formation factor, porosity, permeability. Also a brief description of main laboratory technique is shown. In a following section, we describe more detailed nano-CT technique. Results section contains plots, tables and description of analysed parameters. In the discussion, we compared nano-CT analysis results with the other conventional parameters and discuss usefulness of the CT method in carbonates. New approach is presented: pore size analysis in carbonates based on nano-CT with division into clusters, quantitative interpretation and evaluation of low porosity and low permeability carbonates based only on the results of quantitative analysis of CT images.

New software poROSE was presented as porous materials examination software for images qualitative and quantitative interpretation (Habrat et al. 2017).

Materials and Methods

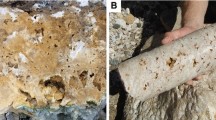

The research material consisted of carbonate samples—limestones (8 samples) and dolomites (9 samples). All samples were collected from several wells located at the northern part of Poland. Six limestone samples belongs to Devonian (D), one to Permian (P) and one to Ordovician (O) age deposits. Among dolomites, four belong to Devonian (D) and five to Permian (P) age deposits.

Conventional petrophysical measurements

Standard laboratory measurements of petrophysical properties (e.g. skeletal density, bulk density, formation factor, P—wave velocity, S—wave velocity, permeability, total porosity, effective porosity) were made for all samples.

The use of different porosity measurement techniques showed the variation of this parameter depending on the measurement method. In this paper, several porosity measurement techniques were used:

-

1)

Helium pycnometer (He pyc) for total porosity measurements (Webb 2001a)

-

2)

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) for total and effective porosity measurements (Coates et al. 1999)

-

3)

Mercury injection capillary pressure (MICP) for effective porosity measurements (Webb 2001b)

Computed X-ray tomography measurements

Computed tomography (CT) is one of the modern techniques for 3D imaging using X-rays. High-resolution X-ray computed tomography, also referred as micro-CT or nano-CT, emerges as the most appropriate technique applied in order to analyse spatial distribution of pores. This non-invasive method provides the information about porosity and internal structure of the pore space including number of pores, channels, connections and directions.

CT measurements were conducted with Nanotom S General Electric nanotomograph working with high power X-ray tube with maximum operating voltage equal 180 kV. In CT technique, X-ray radiation passing through the sample is absorbed. Depending on the object properties, the radiation is weakened in varying degree—usually the highest density of the object, the weakness. Initial 3D data consisting in this case (for most of analysed samples) of 1500 × 1500 × 2500 voxels, where each voxel represents 0.5 × 0.5 × 0.5 μm3 in 3D space, were reconstructed using Feldkamp back-projection method. The back-projection algorithm is a process mathematical relying on obtaining a processed image. Segmentation algorithm, as a next step, consists of following parts: (a) initial processing with median filter, (b) first histogram thresholding, (c) application of Fourier bandpass filter, (d) second histogram thresholding with triangle method, (e) morphological operations combined with median filter.

The results of computerized X-ray nano-CT are presented in the form visualization of 3D pore space. Visualization of the 3D pore space allows on the qualitative interpretation of its distribution, with division objects (pores) into subgroups according to the size of the pores.

The quantitative interpretation of CT images includes determination of petrophysical parameters from the geometrical parameters. The following geometrical parameters were calculated: volume of pores, x, y and z-coordinate of pore centroid, surface area, volume enclosed by surface mesh, moment of inertia around shortest principal axis, middle principal axis and longest principal axis, mean local thickness of pore, standard deviation of the mean local thickness, maximum local thickness, length of best-fit ellipsoid’s long radius, intermediate radius and short radius, Feret diameter, sphericity and pore throat diameters. All these parameters are related to the geometry of the imaged pores. Unfortunately, due to the simplifications used in their calculation (e.g. approximation of the pore shape with the sphere or ellipsoid), not all of them can be correlated with the petrophysical parameters of rocks. In this paper, we focused on parameters which show the relation with the petrophysical properties of rocks: Total Porosity from CT (Φ_CT, volume of pores), %—calculated as a sum of voxels (converted into μm) defined as the pores (low density at the CT images); Surface Area, μm2—calculated as a sum of voxels at the edge of the objects; Thickness (mean local thickness of pores approximate as sphere), μm—defined as a mean local thickness of particle; Pore/Throat—calculated as a mean particle thickness/throat thickness ratio; Feret Diameter, μm—is a measure of an object size along a specified direction. In 3D objects, the Feret diameter is usually defined as the distance between two parallel tangential lines.

Results and discussion

Basic statistics

The basic statistics of conventional petrophysical parameters for analysed lithological types are presented in Table 1 (abbreviations: Ls means limestone, Do means dolomites, He pyc means helium pycnometer, NMR means nuclear magnetic resonance, MICP means mercury injection capillary pressure).

The main goal of the CT measurements is the total porosity calculation. It was done by summarizing the object with the lowest density on the CT images. Results of calculation were added (black points) to the plot in Fig. 1. It can be shown that there is no ambiguous dependency between total porosity from CT and other methods. For same samples, e.g. Ls_D6 or Do_D7 results obtained from CT are almost equal to porosity from NMR. However, in the most cases, e.g. Ls_D3 or Do_P5, porosity from CT is much higher than from the other methods.

Porosity of analysed samples obtained from different measuring technique: He pyc helium pycnometer, NMR nuclear magnetic resonance, MICP mercury injection capillary pressure, CT computed X-ray tomography. Symbols in sample numbers mean: Ls limestone, Do dolomites, O Ordovician age, P Permian age, D Devonian age

Figure 1 shows the values of porosity from various measurement methods, registered for individual samples. In most cases, the total porosity values from He pyc are close to one from NMR (except samples number Do_P4 and Do_P5, where porosity from NMR are much higher than from He pyc). Similar situation can be observed for effective porosity from NMR and MICP (except sample Do_P5). The largest spread of the values of total porosity from three methods CT, NMR and He pyc was observed for Ls_O1, Ls_D3, Ls_D5 and Do_P5 samples.

There are several reasons for such large differences:

-

various physical phenomena on which measurement methods are based,

-

various measurement resolution limits,

-

measurements were made on the three different fragments of rock, taken from the same depth. If the rock shows high heterogeneity, it may turn out that the porosity values will be different.

The discrepancy in the results is confirmed only by the fact that the measurements of carbonate rock samples are largely dependent on the test method, the heterogeneity of the material and the representativeness of the material collected for testing. Total porosity from NMR is a function of the amount of hydrogen in the sample. The total helium (He) porosity depicts the volume of pores to which gas has penetrated. Total porosity from CT is calculated on the basis of tomographic images, so it is the number of voxels with an appropriate shades of grey (pores are indicated as black objects) in the grey scale. Each of these methods has its limitations. In most of the samples, similar values for NMR and He porosity were obtained. Effective porosity obtained from NMR and from MICP is also similar in most cases. The highest differences are observed for samples Do_P5 (differences in total and effective porosities) and Do_P4 (differences only in total porosity).

In the context of the above-mentioned possible causes of discrepancies in the values of porosity, it is difficult to indicate which value is closest to the real one. According to the authors, it is more desirable to consider the obtained results in the context of differences in measurement methods, e.g. higher NMR porosity than porosity from other methods, may suggest the presence of bound water or the presence of isolated pores. Higher porosity from CT than porosity from other methods may suggest the presence of isolated, unconnected pores. Lower values of CT porosity than those obtained from NMR or He pyc may indicate the presence of pores smaller than the resolution of the computed tomography.

Interpretation of CT images

Qualitative interpretation of CT images was performed in poROSE software developed for image analysis and dedicated for rocks.

For each sample, the results of the total porosity determination were the basis of the pore space division into classes. Objects were divided into classes regarding their volume. Volume class units are represented as voxel. In the presented results, 1 voxel (v) is equal to 0.5 × 0.5 × 0.5 = 0.125 µm3 and is the smallest volume, which can be detected using nano-CT.

For analysed samples, total pore space was divided into 6 groups:

-

A—volume from 0.125 to 1.125 μm3 (1–9 voxels);

-

B—volume from 1.25 to 12.375 μm3 (10–99 voxels);

-

C—volume from 12.5 to 124.875 μm3 (100–999 voxels);

-

D—volume from 125 to 1249.875 μm3 (1000–9999 voxels);

-

E—volume from 1250 to 12,499.875 μm3 (10,000–99,999 voxels);

-

F—volume up to 12,500 μm3 (up to 100,000 voxels).

Figure 2 gives an example of the pore space division. Orange selections depict the pores from group C, yellow—from group D, green—from group E and blue—from group F.

Results of object size classification for selected samples in poROSE software: a sample no. Ls_D6, b sample no. Ls_P1, c samples no. Do_P4. Colours reflect to the volume of the pores: red (group A and B)—volume from 1 to 99 voxels; orange (group C)—volume from 100 to 999 voxels; yellow (group D)—volume from 1000 to 9999 voxels; green (group E)—volume from 10,000 to 99,999 voxels; blue (group F)—volume up to 100,000 voxels

Objects belonging to groups A and B (Table 2) are almost invisible on the photo scale (Fig. 2). Sample Ls_D6 (Fig. 2a) provides an example of a pore system that is dominated by isolated, medium size pores. Large pores (blue objects) presented on the top of visualization, create a main part of samples porosity. Total number of objects/pores in this sample (2516) is relatively small (Table 2), what resulting in low calculated pore volume from nano-CT. Twice as much pores/objects were calculated for sample Ls_P1. For this sample, CT porosity is equal to 4.3%.

When we compare samples Ls_P1 with the sample Do_P4, we can observe visible differences. Total number of objects in both samples is similar (about 4000); significant differences exist in the number of objects belonging to the different classes (especially F). This difference also results in different porosities (Table 2).

Quantitative analysis was made for whole pore space in the samples and for the classes obtained from qualitative image interpretation. Number of objects assigned for each class in each sample was shown in Table 2. It can be observed that the highest number of identified objects is not always related to the highest porosity, for example: for sample Ls_O1 39,235, objects were counted, but they were mostly small (mostly groups B and C). For limestones, the number of objects with high pore volume classes is limited. The exception is sample Ls_D3 with the highest total CT porosity (10.5%), which have 450 objects in classes F (highest volume). In dolomites samples, the highest CT porosity (10.4%) was observed for sample Do_P5. In this sample also, the highest number of objects was registered (202 in class F). Similar to the limestones groups, the highest number of objects was registered in classes B and C.

Figures 3 and 4 depict the relations between some of them, where colours mean different classes of object size. In the CT images, there was found porosity equal 0% for 3 samples: Ls_D2, Do_D10 and Do_P6. It means that in this samples pore sizes are smaller than the CT resolution or that the samples were no representative. Measured NMR, MICP and He pyc porosity for that samples are also very low. Figure 3 shows the dependence of the Feret diameter on the specific surface area. Two linear trends can be observed for limestones. For a given surface area, it was noted that the three Devonian samples Ls_D3, Ls_D4 and Ls_D5 show smaller values of Feret diameters from the remaining samples. Among the dolomites, a linear relationship was observed for all samples. Figure 4 shows the dependence of the Surface Area/Feret Diameter ratio and Thickness (calculated as a mean local thickness of the particle). For both, limestones and dolomites were observed a division into two groups. Among the limestones, different relations from the rest of the samples were observed for the Ls_D6 sample (for the same thickness the value of the quotient is higher). Among the dolomites, for the Do_P3 and Do_P4 samples it was found that the Surface Area/Feret Diameter ratio is smaller than for the other samples in the same thickness ranges. Presented relations indicate differences in the development of the pore space of the analysed samples.

Average values of CT image parameters were calculated for each sample. Figure 5 depicts exemplary relations between these parameters and results of standard petrophysical laboratory measurements. To the laboratory results was added FZI (Flow Zone Index), as a parameter connecting porosity and permeability (Amaefule et al. 1993, Prasad 2000, Tiab and Donaldson 2000; Jarzyna et al. 2009). The FZI contains information on rock ability to transport fluid through its pore space. Reservoir parameters in units with constant FZI undergo only small changes.

There were calculated Pearson correlation coefficients (R) for all samples and for limestones and dolomites separately.

For limestones, the best linear relationship was observed between:

-

CT Porosity and P-wave velocity (R = − 0.6) and Clay Bound Water (R = 0.6);

-

Average Surface Area and P-wave velocity (R = − 0.5), FZI (R = 0.65) and Permeability (R = − 0.5);

-

Average Thickness and FZI—Flow Zone Index (R = 0.6) and Effective Porosity from NMR (R = − 0.45);

-

Average SA/FD (Surface Area/Feret Diameter) and P-wave velocity (R = 0.7);

-

Average Pore/Throat ratio and P-wave velocity (R = − 0.5).

For dolomites, the best linear relationship was observed between:

-

CT Porosity and P-wave velocity (R = 0.5), Clay Bound Water (R = 0.6) and Effective Porosity from NMR (R = 0.6);

-

Average Surface Area and Clay Bound Water (R = 0.9), Effective Porosity from NMR (R = 0.75), Effective Porosity from MICP (R = 0.97) and P-wave velocity (R = 0.6);

-

Average Thickness and FZI—Flow Zone Index (R = − 0.7), Effective Porosity (from NMR and MICP) (R = 0.6) and Permeability (R = − 0.6);

-

Average Pore/Throat ratio and FZI (R = − 0.7).

Summing up the obtained relationships, it should be noted that the geometrical parameters obtained from CT images can be combined with the standard results of laboratory measurements. Much better linear relationship was obtained for the dolomites than for limestones. This may be related to the diversities of the limestone group (Figs. 3a, 4a). The combination of parameters, e.g. Surface Area and Feret Diameter, or porosity and permeability (as FZI) improved the relationship between the parameters. FZI shows a high correlation with average thickness, but also with SA/FD ratio. It shows that the hydraulic flow ability described by FZI can also be specified using parameters obtained from CT.

The obtained parameters from CT images and relations with standard petrophysical parameters allow to conclude that the applied algorithms are useful in assessing the structure of pore space. On the basis of the tested samples, due to the high heterogeneity of carbonates, the authors did not attempt to generalize the results in relation to whole reservoirs.

Conclusions

The article presents the use of geometric parameters for image analysis to assess the properties of rocks.

-

Nanotomography allowed analyzing the pore space structure. Nano-CT images informed about the pore space parameters graphically and numerically (qualitative and quantitative). Advantages of using CT are: (a) pore visualization, (b) pore class division, (c) calculation of parameters for pore classes, e.g. porosity, tortuosity, surface area.

-

Qualitative analysis allows to find pores orientation in pore space formation, microfractures presence and their directions, porosity values and distribution. The division of the pore space into groups depending on the pore size was obtained. This division shows the internal pore structure of rocks, allows full characterization of reservoir abilities (simulations of fluid and gas flows based on CT images).

-

Quantitative analysis allows determining such parameters as average pore diameter or specific surface area. There was a strong linear relationship between the Feret Diameter and the Surface Area. Dividing these two parameters allowed refining the relationship and linking it to the local thickness of particle.

-

The combination of geometrical parameters obtained from CT images gives new, unique information about the analysed samples.

-

The combination of CT parameters and standard laboratory measurements results gives the possibility to describe fluid flow ability based on CT images—without complicated calculations.

-

3D investigations in nano-CT explained the complexity of pore space in tight carbonates.

-

poROSE (poROus materials examination SoftwarE) is a new tool which is dedicated to rock analysis. The software is useful and gives many advantages in rock analysis.

It can be concluded that computed tomography is a powerful tool in rock analysis and can be used for low porosity and low permeability carbonates. The use of CT images helps in the assessment of reservoir parameters of even very heterogeneous and complicated pore structures that are observed in carbonates.

References

Akbar M, Petricola M, Watfa M, Badri M, Charara M, Boyd A, Grace M, Kenyon B, Roestenburg J (1995) Classic interpretation problems: evaluating carbonates. Oilfield Rev 7:38–57

Amaefule JO, Altunbay M, Tiab D, Kersey DG, Keelan DK (1993) Enhanced reservoir description: using core and log data to identify hydraulic (Flow) units and predict permeability in uncored intervals/wells. In: SPE annual technical conference and exhibition, Houston (3–6 October), paper SPE-26436-MS. https://doi.org/10.2118/26436-ms

Arns CH, Bauget F, Ghous A, Sakellarion A, Senden TJ, Sheppard AP, Sok RM, Pinczewski WV, Kelly JC, Knackstedt MA (2005) Digital core laboratory: petrophysical analysis from 3D imaging of reservoir core fragments. Petrophysics 46(4):260–277

Coates GR, Xiao L, Prammer MG (1999) NMR logging principles & applications. Halliburton Energy Services, Houston

Dohnalik M (2013) Improving the ability of determining reservoir rocks parameters using X-ray computed microtomography. Ph.D. Thesis, AGH University of Science and Technology, Kraków, Poland

Exner U, Barnhoorn A, Baud P, Reuschlé T (2015) Porosity, permeability and 3D fracture network characterisation of dolomite reservoir rock samples. J Pet Sci Eng 127:270–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2014.12.019

Habrat M, Krakowska P, Puskarczyk E, Jędrychowski M, Madejski P (2017) The concept of a computer system for interpretation of tight rocks using X-ray computed tomography results: technical note. Stud Geotech Mech 39(1):101–107

Jarzyna J, Puskarczyk E, Bała M, Papiernik B (2009) Variability of the Rotliegend sandstones in the Polish part of the Southern Permian Basin—per meability and porosity relationships. Ann Soc Geologorum Poloniae 79:13–26

Jaworowski K, Mikołajewski Z (2007) Oil-and gas-bearing sediments of the Main Dolomite (Ca2) in the Międzychód region: a depositional model and the problem of the boundary between the second and third depositional sequences in the Polish Zechstein Basin. Geol Rev 55(12/1):1017–1024

Krakowska P, Puskarczyk E (2015) Tight reservoir properties derived by nuclear magnetic resonance, mercury porosimetry and computed microtomography laboratory techniques: case study of palaeozoic clastic rocks. Acta Geophys 63(3):789–814

Krakowska P, Puskarczyk E, Jędrychowski M, Habrat M, Madejski P, Jarzyna J (2017) Analiza petrofizyczna łupków sylurskich z synklinorium lubelskiego—petrophysical analysis of Silurian shales from the Lublin. Zeszyty Naukowe Instytutu Gospodarki Surowcami Mineralnymi i Energią PAN 101:293–301

Mazzullo SJ, Chilingarian GV (1992) Diagenesis and origin of porosity. In: Chilingarian GV, Mazzullo SJ, Rieke HH (eds) Carbonate reservoir characterization: a geologic-engineering analysis Part I: Elsevier Publ. Co., Amsterdam, vol 30. Developments in Petroleum Science., pp 199–270

Prasad M (2000) Velocity-permeability relations with hydraulic units. Geophysics 68:108–117

Teles AP, Lima I, Lopes RT (2016) Rock porosity quantification by dual-energy X-ray computed microtomography. Micron 83:72–78

Tiab D, Donaldson EC (2000) Petrophysics, theory and practice of measuring reservoir rock and fluid transport properties, 2nd edn. Elsevier, N.Y., p 899

Wardlaw NC (1996) Factors affecting oil recovery from carbonate reservoirs and prediction of recovery. In: Chilingarian GV, Mazzullo SJ, Rieke HH (eds) Carbonate reservoir characterization: a geologic-engineering analysis, Part II, vol 44. Developments in petroleum science., pp 867–903

Webb PA (2001a) Volume and density determinations for particle technologists. Micromeritics Instrument Corp., World Wide Web www.micromeritics.com. Accessed 22 May 2018

Webb PA (2001b) An introduction to the physical characterization of materials by mercury intrusion porosimetry with emphasis on reduction and presentation of experimental data. Micromeritics Instrument Corp., World Wide Web www.micromeritics.com. Accessed 22 May 2018

Wei X, Chen H, Zhang D, Dai R, Guo Y, Chen J, Ren J, Liu N, Luo S, Zhao J (2017) Gas exploration potential of tight carbonate reservoirs: a case study of Ordovician Majiagou formation in the eastern Yi-Shan slope, Ordos Basin, NW China. Pet Explor Dev 44(3):347–357

Wennberg OP, Rennan L, Basquet R (2009) Computed tomography scan imaging of natural open fractures in a porous rock; geometry and fluid flow. Geophys Prospect 57(2):239–249

Acknowledgments

poROSE software is created thanks to the funding of the project LIDER/319/L–6/14/NCBR/2015: Innovative method of unconventional oil and gas reservoirs interpretation using computed X-ray tomography. The project is funded by the National Centre for Research and Development in Poland, program LIDER VI, project no. LIDER/319/L–6/14/NCBR/2015: Innovative method of unconventional oil and gas reservoirs interpretation using computed X-ray tomography. The authors wish to thank the Polish Oil & Gas Company for the data and core samples.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Puskarczyk, E., Krakowska, P., Jędrychowski, M. et al. A novel approach to the quantitative interpretation of petrophysical parameters using nano-CT: example of Paleozoic carbonates. Acta Geophys. 66, 1453–1461 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11600-018-0219-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11600-018-0219-x