Abstract

With the emergence and dissemination of the COVID-19 pandemic and the transformation of education to online classes, it is important to explore the effects of online learning on EFL learners’ psychological factors in the Iranian EFL learners. Hence, this study aims to explore the effects of online learning on EFL learners’ motivation, anxiety, and attitude. For this purpose, using a convenience sampling method, a total of 293 upper-intermediate EFL learners at Iran Language Institute in Ahvaz, Iran, took the Oxford Quick Placement Test, and 200 EFL learners whose scores fell around the mean were selected and assigned randomly to an experimental group and a control group. The participants’ motivation, anxiety, and attitudes were measured before and after the treatments (lasting 10 one-hour sessions held once a week) using validated questionnaires. The collected data were analyzed through a one-way MANOVA test and a one-sample t-test. The findings evidenced that online learning positively affected the participants’ motivation, anxiety, and attitudes. That is, due to the online learning, their motivation increased, their anxiety lowered, and positive attitudes were shaped toward L2 learning. Finally, based on the findings, some implications are proposed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Several factors are involved in learning English as a second language (L2); the most important factors are psychological attributes (Haidara, 2016; Hashemifardnia et al., 2021) including attitude, aptitude, intelligence, anxiety, and motivation (Qureshi et al., 2020; Rahimi & Fathi, 2021). Among these factors, motivation is the key factor affecting L2 learners’ achievement (Derakhshan et al., 2021; Ehrman & Oxford, 1995; Gradman & Hanania, 1991; Gardner & MacIntyre, 1991; O’malley & Chamot, 1990; Pawlak et al., 2021; Riding & Cheema, 1991). Harmer (2007) defines motivation as “the dynamically changing cumulative internal drives in people that initiate, direct, coordinate, amplify, terminate, and evaluate the cognitive and motor processes” (p. 98). By these drives, initial wishes and desires are chosen, prioritized, operationalized, and successfully or unsuccessfully acted out. Motivation is also characterized as an internal drive that pushes people to do things to reach their intended goals (Harmer, 2007; Melhe et al., 2021). As pointed out by Brown (2000), motivation is a construct applied to indicate the success or failure of challenging tasks.

Another psychological factor influencing L2 learning is anxiety. It refers to “the subjective feelings of tensions, apprehensions, nervousness, and worries concerned with an arousal of the autonomic nervous systems (Dörnyei, 2011). According to Zhang (2001), language anxiety is the psychological tension that L2 learners go through in conducting learning tasks. Language anxiety includes the negative feeling of worries and fear-related emotions concerned with utilizing or learning a language which is not an individual’s native language (Dörnyei, 2005; MacIntyre & Gregersen, 2012; Tahmouresi & Papi, 2021).

Attitude is another psychological factor affecting L2 learning. A positive attitude toward L2 learning is facilitative, but a negative attitude toward L2 learning is a hindrance (Knouse et al., 2021). L2 learners’ attitude can be defined as a collection of feelings considering language use and its status in the community. According to Gardner (2010), attitude is the evaluative reactions to some referents or attitude objects based on the people’s beliefs or ideas about the referents. It seems that having a positive attitude toward L2 and its native speakers can be anticipated to develop learning while having a negative attitude can hinder it (Ahmed et al., 2015).

Over the last years, due to the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, all nations have been immensely affected. They have faced challenging problems, which inevitably have influenced the educational system as well, with unpleasant consequences for instructors and students. Online learning seems to be the best compensation for the lack of education (Wolfinger, 2016). These unexpected modifications might produce some problems in ensuring the effectiveness of education in online classes (Hasan & Bao, 2020; Mahyoob, 2020; Rapanta et al., 2020).

Considering the importance of psychological factors, such as motivation, anxiety, and attitude in L2 learning and the quick extensive shift to online learning, it is essential to explore the effects of online learning on EFL learners’ motivation, anxiety, and attitude. However, a cursory glance at the literature reveals that this issue has remained unexplored in the Iranian EFL context. Therefore, the present study aims to further our understanding of the effects of online learning on EFL learners’ motivation, anxiety, and attitude. The findings of the present study may be helpful for EFL teachers to create a learning setting in which EFL learners get motivated, handle their anxiety, and shape positive attitudes toward L2 learning.

Review of the literature

Motivation in L2 learning

Psychological factors, including motivation, anxiety, and attitude, are mentally dealt with by L2 learners. It is evident that in L2 education, learners’ motivation is crucial for their intended achievements (Tejada Reyes, 2019; Tuan, 2012). As stressed by Sara et al. (2017), motivation is the main factor influencing L2 learners’ success or failure. Ryan and Deci (2000) note that having motivation implies being moved to conduct a task or an activity. Contrary to unmotivated students, motivated students are energetic and dynamic to accomplish the given tasks. Interest, curiosity, and desire to do a task are the primary agents that compose motivated students (Gardner, 2010; Kim & Kim, 2021; Williams & Burden, 1997). In sum, the concept of motivation includes behavioral aspects which relate to individuals’ needs, expectations, and goals (Esra & Sevilen, 2021; Esteves et al., 2021; Steers & Porter, 1991).

There are two sorts of motivation, including intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic motivation refers to the effects of the inside aspects of people; intrinsically motivated students try to meet personal needs. Dörnyei (1998) asserted that intrinsically motivated students acquire language for their own self-perceived needs and objectives. Furthermore, Dörnyei and Ushioda (2013) stress that intrinsic motivation deals with conducting something since it is innately interesting or pleasurable. In contrast, the extrinsic motivation is produced by outside agents. In other words, it is the motivation associated with the external factors that influence students’ attitude toward learning, for example, learning to find a job, make money, or get good scores. According to Dörnyei (2011), extrinsically motivated individuals carry out the tasks hoping to receive outward results and prizes. Some other classifications of motivation are available in the literature. For example, Wang and Guan (2020) classify motivation into positive and negative (demotivation) types. Motivation in this conceptualization would yield either facilitative or debilitative results.

The primary motivation theories include Behavioral, Cognitive, and Humanistic. From the perspective of behaviorism, motivation is a matter of rewards that perform as the reinforcers for proper behavior. Behaviorists claim that students try to do identical behaviors if they have previous experiences with a reward, for instance, teachers’ praises and grades (Brown, 2004). The cognitive perspective of motivation claims that individuals control their actions and make decisions on their own to reach the intended objectives (Deci & Ryan, 1975). Humanistic perspectives of motivation consider the individual as a whole and investigate the interrelationship of the various human needs. One of the most prominent humanistic theories is the Abraham Maslow hierarchy of needs. He categorized the needs into two main classifications: deficiency and growth. The deficiency needs are physiological, safety, belongingness and love, and esteem needs. The growth needs are cognitive needs, aesthetic needs, and self-actualization (Sara et al., 2017).

When it comes to online learning, motivation needs considerable attention (Hartnett, 2016; Li & Tsai, 2017; Özhan & Kocadere, 2020). According to Hartnett (2011), it is a complex concept which is affected by internal, external, and personal factors. As highlighted by Song (2000), internal factors deal with the characteristics of the course which may affect students’ motivation. External factors are related to the features of the learning environment that may influence students’ motivation. Personal factors refer to the changes in students’ motivation that may be created by the traits of students. As students are not highly inclined to join online classes and the attrition rates are high, their motivation should be examined carefully (Kim & Frick, 2011).

Anxiety in L2 learning

The other psychological factor affecting EFL learners’ achievement is anxiety. It is ubiquitous among EFL learners and defined as negative feelings of apprehension during examinations, presentations, and public speech. This reduces their energy and concentration to successfully complete academic tasks. (Dörnyei, 2011; Horwitz, 1986). The concept of anxiety in L2 learning has gained the status of a precise technical notion (Tahmouresi & Papi, 2021; Young, 1994), with more consonant research results of the negative impacts of language anxiety on L2 learners’ achievement (e.g., Horwitz 1991; MacIntyre, 1988; Qinghua, 2021; Tallon, 2009).

Psychologists have identified three types of anxiety: trait anxiety, state anxiety, and situation-specific anxiety (Dörnyei, 2011). Trait anxiety refers to the global or general anxiety and students’ constant feelings of anxiety in different situations (Brown, 2000). State anxiety is referred to feelings of stress and fears when students experience when they face threats. Situation-specific anxiety is a type of anxiety in which students are anxious in particular contexts (Dörnyei, 2011). According to Horwitz (1986), tests, communication apprehensions, and peer evaluations are the three primary sources of anxiety. However, other factors, such as stage fear, the fright of being laughed at, students’ personality, teachers’ teaching styles (Oxford, 1999; Madjid & Samsudin, 2021; Sudina & Plonsky, 2021), students’ learning styles, learning situation itself, first language (L1) skills and the whole process of L2 learning can be the causes of anxiety (Reid, 1995; Sudina & Plonsky, 2021).

The previous studies have shown that language anxiety can influence language skill enhancement in various areas: communication apprehension (Daly & McCroskey, 1994), reading comprehension (Saito et al., 1999), oral proficiency (Young, 1992), communicative skills (Phillips, 1999), writing skills (Leki, 1999; Tahmouresi & Papi, 2021), and listening skills (Vogely, 1999). The literature review implies that L2 teaching/learning methodologies should reduce the level of anxiety and tension among high–anxious learners to decrease the pervasive cognitive, academic, social, and personal undesirable impacts on L2 learning settings (Horwitz, 2001; Namaziandost et al., 2022a, b; Young, 1999).

Attitude in L2 learning

When it comes to L2 learning, undoubtedly, attitude is one of the significant personality factors that indirectly affects the levels of proficiency obtained by L2 learners. According to Montero et al. (2014), how L2 learners develop their competence is mainly affected by their attitude toward either a target language or a target culture. Baker (1992) defines “attitude as a hypothetical concept applied to describe the directions and perseverance of people behavior” (p. 10). The previous studies have indicated that attitude plays a key role in L2 learners’ final achievement (Azizi et al., 2022; Bal-Taştan et al., 2018; Hosseini & Pourmandnia, 2013; Namaziandost et al., 2022a, b; Tsunemoto & McDonough, 2021). There are two reasons why investigation on L2 learners’ attitude is significant. First, the attitude toward learning affects L2 learners’ behaviors (Moskowitz & Dewaele, 2021; Moşteanu, 2021; Weinburgh, 2000). Second, a positive correlation between the attitude and L2 learners’ achievements has been found (Tsunemoto & McDonough, 2021; Weinburgh, 2000).

Lambert (1967) suggests two kinds of attitude toward L2 learning: ‘integrative’ and ‘instrumental.’ The integrative attitude is a desire to know and get friendly with language speakers. However, an instrumental one is a desire to better oneself materially through the language. He adds that the integrative attitude is more likely to succeed than an instrumental one.

When students have the required readiness, it can be assured that the intended educational objectives can be realized in online classes (Hukle, 2009). L2 learners do not achieve the required readiness unless they enjoy positive attitudes toward online classes (Kruger-Rose & Waters, 2013). In other words, as highlighted by Usta (2011), L2 learners’ attitude toward instructional programs is a determining factor for their success or failure. In online classes, L2 learners’ attitudes are shaped by cognitive, effective, and behavioral aspects. In online classes, L2 learners shape positive attitudes by reacting to all stimuli of the virtual contexts, making active their own desire, energy, and thoughts, responding to the effect, and changing it into behaviors. In sum, L2 learners’ attitudes toward online learning can be directly associated with the students’ learning outcomes (Herguner et al., 2020; Usta, 2011).

Online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic

The global outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has exerted dramatic effects on the educational systems around the world, leading to schools and universities lockdown (Carrillo & Flores, 2020; Murphy, 2020). Based on the data released by UNESCO, as cited in Mohammadimehr (2020), more than 1.5 billion students have been influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic, and they have experienced radical educational changes. Educational centers have faced unanticipated challenges during these challenging times. In response to this worldwide emergency, they have resorted to online learning (Mohammadimehr, 2020; Sahu, 2020; Shahidi, 2020). Indeed, online learning is an appropriate option for teaching different courses because it has been developing for years and has provided new chances for students, instructors, educational planners, and institutions (Rahimi et al., 2021; Mayadas et al., 2009). Online learning, created and evolved with the advent of the Internet and the development of technology, involves designing, compiling, presenting, and evaluating students’ learning and uses e-learning capabilities to facilitate it (Ahmed & Al-Kadi, 2021; Shafiee Rad et al., 2022; Moore & Kearsley, 2011). However, to make the way for efficient learning of students, it is necessary to transcend emergency online practices and create quality online learning activities that stem from meticulous instructional designs and plans (Hodges et al., 2020). In this virtual environment, the affective factors, such as motivation, anxiety, and attitudes may play a key role in students’ learning. Therefore, it is essential to explore and consider them in online classes.

Education officials seem to have to look for other alternatives for face-to-face education. The main alternative has been online learning which has absorbed noticeable attention across the globe. Here, we critically review some of the studies which have addressed this issue. In a study, Ahmed and Elttayef (2016) explored the effects of applying Skype as a social instrument network on boosting English students’ discourse competence. Their findings revealed that the Skype tool positively influenced the participants’ discourse competence. Further, Abbasi et al. (2020) explored the effects of using the Moodle course management system on improving EFL learners’ speaking skills. Their results indicated that the Moodle course management system was useful to boost the participants’ speaking skills.

Additionally, Alipour and Ehmke (2020) inspected the impacts of online vs. blended learning on enhancing Iranian EFL learners’ vocabulary learning. The results documented that the learners who received instruction through both online and blended learning outperformed the control group. Moreover, their findings revealed no remarkable difference between the online and blended learning groups in terms of gains of learning. Besides, Razmjou (2021) examined the effectiveness of online learning compared with face-to-face learning in cultivating Iranian EFL learners’ achievement. The results revealed that the participants who were intruded through online classes performed as good as the participants who joined the face-to-face classes. Likewise, Namaziandost et al. (2021) examined the potential impacts of applying WeChat-based online instruction on Iranian EFL learners’ vocabulary development. Their results showed that the WeChat-based online instruction improved significantly the participants’ vocabulary learning. Moreover, Meşe and Sevilen (2021) conducted a qualitative case study to examine L2 learners’ perceptions of online instruction and how it influenced their motivation over a period of a seven-week course. Both interviews and creative writing tasks indicated that the students believed that the online learning negatively affected their motivation due to a lack of social interactions, a mismatch between expectations and contents, organizational problems, and the organization of learning situations. Besides, Hashemifardnia et al. (2020) examined the effects of Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) on Iranian EFL learners’ speaking complexity, accuracy, and fluency. The findings showed that there were significant differences between the post-test of the experimental group and the control group with regard to the gains of speaking. In addition, the results indicated that the participants held positive attitudes toward using MOOC instruction for raising speaking ability. Finally, Dirjal et al. (2021) inspected the effects of Skype on enhancing EFL students’ listening and speaking skills. The outcomes of the research uncovered that after receiving their teaching instructions via Skype tool, the experimental participants were highly motivated in their listening and speaking skills. As a result, a remarkable difference was found between the experimental group and the control group in terms of listening and speaking performance at the end of the instruction.

Having reviewed the literature, it is clear that most investigations examined the effects of online learning on improving the four primary language skills, and very few studies have addressed the impacts of online learning on psychological factors among Iranian EFL learners. In response to this long-lasting gap in the literature, the present study sought to investigate the effects of online learning on Iranian EFL learners’ motivation, anxiety, and attitudes during the COVID-19 pandemic. To meet these objectives, the following research questions were put forward:

-

RQ1. Does using online learning have any significant effects on Iranian EFL learners’ motivation and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic?

-

RQ2. Do Iranian EFL learners hold positive attitudes toward using online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Methodology

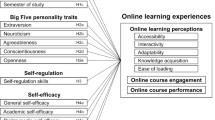

The researchers used a quasi-experimental design to run the present study. According to Riazi (2016), a quasi-experimental design is used to manipulate an independent variable to reveal its effects on one or more dependent variables and distribute participants into experimental and control groups to derive cause and effect relationships using statistical analysis. Having homogenized the participants, two groups, namely an experimental group and a control group, were made up and went through pre-test, treatment, and post-test procedures. Therefore, using a quasi-experimental design, the present study explored the effects of online learning on Iranian EFL learners’ motivation, anxiety, and attitude.

The present study was run at Iran Language Institute (ILI) in Ahvaz, Iran. ILI is a non-profit language organization in Iran with the national mission of developing foreign language learning. It has a lot of branches across the country. Using the convenience sampling method, a total of 293 upper-intermediate EFL learners took the Oxford Quick Placement Test (OQPT) and the learners whose scores (n = 200) fell around the mean were selected and assigned randomly to an experimental group (n = 100) and a control group (n = 100). The convenience sampling method is a non-probability sampling where the sample is chosen solely based on the convenience (Mackey & Gass, 2015). The participants included just male students due to gender segregation in educational centers in Iran. They aged from 17 to 33 years old and were learning English as a foreign language four hours per week. It is worth noting that the participants expressed orally their consent to participate in the study. The researchers ensured that their responses during the study would remain confidential and they would be kept informed about the final findings.

To carry out this research study, some distinct steps were taken. At first, a total of 200 upper-intermediate participants who had been homogenized using OQPT were selected, and assigned to two groups, namely an experimental group (n = 100) and a control group (n = 100). Then, the FLCAS and the AMTB questionnaires were administered to all the sub-groups to measure their anxiety and motivation before introducing the treatment. Afterwards, the respondents in the experimental sub-groups were sent the materials online via Skype application since they all had easy access to this application. The researchers held online classes for the experimental sub-groups, and five lessons from Family and Friends Book 5 were taught to this group. On the other hand, the participants in the control group were taught using a traditional method that was not equipped with the Internet, and the Skype application. One of the researchers attended the class personally and started to teach the lesson to the control group. He provided synonyms and antonyms for the words, played the audio files of the conversations, taught the grammar inductively, and asked the students to do the practices and do the workbook at home. After teaching each lesson, the researchers gave a related exam to the students. This procedure continued till teaching five lessons to the students of all the sub-groups. The study lasted 10 one-hour sessions (one session per week). In the first, second, and third sessions, the OQPT test, the FLCAS, and the AMTB questionnaires were administered respectively. During 5 sessions, the treatment (teaching five lessons) was conducted; in the following ninth and tenth sessions, the FLCAS and the AMTB questionnaires were administered again as the post-tests of the study. The attitude questionnaire was administered only to the experimental sub-groups to check their opinions about online instruction in the last session. Of particular note is that the instruments were administered on the same date to meet the ethical requirements.

Instruments

To run the present study, the researchers used four instruments to collect the required data. The first instrument was the Oxford quick placement test (OQPT) to make the participants homogenized. The primary reason for using the OQPT was that it is widely used to determine EFL learners’ proficiency. It included 60 multiple-choice items measuring the language proficiency of English learners. According to the suggested band scores, the students who scored from 40 to 48 were considered upper-intermediate and selected as the target participants of the present study.

The second instrument included the Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS) questionnaire, designed and validated by Horwitz (1986). As the name suggests, it was used to gauge the participants’ anxiety before and after the treatment. FLCAS consists of 33 items to measure the participants’ responses based on a five-point Likert scale from Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree.

The third instrument was a questionnaire adapted from Gardner’s (2004) international version of the Attitude/Motivation Test Battery (AMTB) used to measure the participants’ attitudes and motivation. The original test battery consisted of 12 scales with 104 items merged into six variables. However, in the current study, the items of the questionnaire were focused on measuring integrative motivation, instrumental motivation, attitudes toward learning situations, and students’ motivation with 74 items. The scale used in the questionnaire was a five-point Likert-type scale from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (5).

The last instrument entailed an attitude questionnaire given to the respondents of the experimental group to probe their attitudes toward using online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. The researchers designed the questionnaire by reviewing the related literature on online learning. This questionnaire contained 20 items (see Appendix 1). The scale used in the questionnaire was a five-point Likert scale from Strongly disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (5).

It should be noted that the researchers recruited two experts in translation to back-translate the questionnaires, meaning to translate it from English to Persian and then back to English. The primary reason was to avoid any misunderstanding on the part of the respondents and increase the validity of their answers. The instruments were piloted on a sample of 130 students whose language proficiency, age, and gender were the same as the target participants to check the credibility of the instruments. The exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was run at this stage. The following steps were taken to conduct the EFAs: (a) checking the data set, (b) selecting a factor extraction method, (c) determining the number of factors retained, (d) choosing a factor rotation method, and (e) interpreting the factor solution. The preliminary tests of normality for the items of each questionnaire showed no deviations from normality. The correlation matrixes were used to screen the items. Normally, the coefficients below 0.3 and greater than 0.9 should be eliminated. The determinant values of the correlation matrixes were greater than the necessary value of 0.00001 in all utilized questionnaires, indicating that there were no multicollinearity effects in the data. A principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted on the 44 items with orthogonal rotation (varimax). The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure verified the sampling adequacy for the analysis, KMO = 0.802 for FLCAS, and 0.783 for the Attitude towards Online Learning Questionnaire. Additionally, all KMO values for individual items were > 0.71. Also, Bartlett’s test of sphericity indicated that correlations between items were sufficiently large for PCA. Values above 0.4 were retained and the final rotated correlation matrix showed each item had the highest loading on the evaluated construct. As the instruments were back-translated, the researchers also measured their construct validity using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The CFA was used with the participants in the main study (N = 200). The analyses were run via AMOS (v. 24) using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method. The resulting CFA analyses showed a good it to the data in the measurement model for the FLCAS (χ2 = 7.32, df = 4, χ2/df = 1.63, CFI = 0.98, GFI = 0.99, AGFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.07, PCLOSE = 0.32). the CFA analyses for the AMTB also showed a good fit to the data (χ2 = 6.52, df = 5, χ2/df = 1.12, CFI = 0.99, GFI = 0.99, AGFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.06, PCLOSE = 0.63). Finally, the CFA for the Attitude towards Online Learning Questionnaire yielded a good fit to the data, (χ2 = 6.52, df = 13, χ2/df = 1.38, CFI = 0.99, GFI = 0.99, AGFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.05, PCLOSE = 0.78).

Additionally, two university professors in Applied Linguistics were invited to assess the face and content validities of the instruments. Overall, they reported that they enjoyed the required face and content validities. Based on these findings, the researchers assured that the instruments enjoyed the required validity. Concerning the reliability, it was measured using Cronbach’s Alpha. The results yielded (α = 0.98) for the OQPT, (α = 0.86) for FLCAS (the anxiety part), (α = 0.86) for FLCAS (the motivation part), and (α = 0.88) for the attitude questionnaire.

Data analysis procedures

The collected data were analyzed through SPSS, version 22. First, the basic descriptive statistics, such as mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) were calculated. Second, a one-way MANOVA was used to determine the effects of the treatment on the participants’ motivation and anxiety. Finally, a one-sample t-test was used to analyze the data gathered via the attitude questionnaire.

Results

Before running the one-way MANOVA test, the researchers checked out the required assumptions, including multivariate normality, homoscedasticity, linearity, independence, and randomness. Moreover, the correlations between dependent variables ranged between − 0.2 and 0.4. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests of normality and Levene’s tests of variance were above the alpha level of 0.05. Since the outcome variables were normally distributed within each group of the factor variable, the multivariate normality assumption was met. As equal or similar variances in the different groups were compared, the homoscedasticity assumption was met too. Because all of the dependent variables were linearly related to each other, the linearity assumption was met as well. Also, since the participants were randomly assigned to the experimental group and the control group and they just participated in one group, the assumption of independence and randomness was met. Therefore, the researchers could run a one-way MANOVA.

Table 1 reports that the study included one categorical, an independent variable with two levels: the experimental group and the control group. Each group included 100 participants.

As reported in Table 2, M (152.00) and SD (10.53) for the control group and M (66.78) and SD (14.35) for the experimental group were calculated in turn on the anxiety post-test. Additionally, M (338.46) and SD (23.02) for the experimental group and M (160.92) and SD (26.20) for the control group were calculated respectively on the motivation post-test.

To see if there was a statistically significant difference between the obtained means, a one-way MANOVA was run. As reported in Table 3, a Wilk’s Lambda value of 0.007 with a significant value of 0.00 < 0.05 was obtained. That is, using online learning had a significant effect on the Iranian EFL learners’ motivation and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic.

As reported in Table 3, since a significant value was obtained on the multivariate test, it should be examined whether the experimental group and the control group differed on all the dependent measures or just one. This information is presented in Table 4. As a number of separate analyses were involved, a higher alpha level was set to protect against Type 1 error by applying Bonferroni adjustment (Pallant, 2020). In this case, we had two dependent variables to investigate; therefore, 0.05 was divided by 2, giving a new alpha level of 0.025 (Table 5).

As seen in Table 4, two of the dependent variables, anxiety (0.00 < 0.025) and motivation (0.00 < 0.025), recorded a significance value. It indicates that there was a significant difference between the experimental group and the control group regarding both anxiety and motivation.

As observed in Table 7, Partial eta squares of 0.96 and 0.99 for anxiety and motivation, respectively, are considered quite large effect sizes (Tabachnick et al., 2007). The partial eta squares represent the proportion of the variance in the dependent variables that were explained by the independent variable. The large effect sizes indicate that 96% of the variance in anxiety and 99% of the variance in motivation are explained by the independent variable.

As indicated in Table 6, although the experimental group and the control group differed in terms of anxiety and motivation, it cannot be derived from Table 4 which group had higher scores. As presented in Table 5, the mean score for the experimental group regarding anxiety (M = 152.84) was higher than the control group’s mean score (M = 65.93). It also shows that the mean score for the experimental group regarding motivation (M = 339.55) was higher than the mean score of the control group (M = 159.82). To probe if this difference was statistically significant, the researchers run a one-way MANOVA. The results of the one-way MONOVA are presented in Table 7.

As seen in Table 7, there was a statically significant difference between the experimental group and the control group on the combined dependent variables, (F(2, 195) = 1460.10, p < .001; Wilk’s Lambda = 0.007; partial eta squared = 0.99). When the results for the dependent variables were considered separately, anxiety (F(1, 196) = 5328.21, p < .001, partial eta squared = 0.96) and motivation (F(1, 196) = 22985.07, p < .001, partial eta squared = 0.99) were significantly different for the experimental group and the control group, using Bonferroni adjusted alpha level of 0.025. An inspection of the mean scores indicated that the experimental group reported higher levels of anxiety (M = 152.84) and motivation (M = 339.55) than the control group concerning anxiety (M = 65.93) and motivation (M = 159.82), respectively (Table 8).

As noted above, the second research question explored if the Iranian EFL learners held positive attitudes toward online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. To answer this research question, the researchers ran a one-sample t-test. The results are reported in Table 9.

As seen in Table 9, the value of the T-value is 77.66, df = 19, and Sig is 0.02, which is less than 0.05. Thus, it was concluded that the learners had positive attitudes toward online learning to promote their L2 learning during the COIVD-19 pandemic. Furthermore, the eta squared value was 0.86, indicating that there existed a large effect size. That is, the significant changes in the participants’ attitudes could be associated with the independent variable, the online classes.

Discussion

Discussion on the first research question

As noted above, the first research question explored whether online learning significantly affects Iranian EFL learners’ motivation and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings evidenced that compared to the control group, the motivation and anxiety of the experimental group positively changed at the end of the online instruction. Based on the results, it may be argued that these positive changes may be associated with using online learning. In other words, the positive effects of the instruction offered through the Skype application might have helped the participants to reduce their anxiety and increase their motivation. Accordingly, in line with the findings, it is reasonable to argue that the participants might have shaped the positive attitudes toward online learning.

The findings of the study are congruent with those of Dirjal et al. (2021), indicating that the learners who received instruction through the Skype tool got motivated to improve their speaking skills and listening skills. Moreover, the results of the study lend support to those of Terantino (2014), revealing that Skype videoconferencing had positive impact on the improvement of the students’ anxiety.

To recap the discussion of the findings, we can refer to the fact that learning with the Skype application might have provided valuable opportunities for sharing ideas and information. Along with Hashemifardnia et al. (2020), it may be argued that online learning might have assisted the participants to consolidate their knowledge and skills by having easy access to unbounded online resources (Hilliard et al., 2020; Peng et al., 2022). Another line of discussion for the findings may be ascribed to this view that the offering of the instruction through the Skype application might have created a comfortable setting for the EFL learners to interact freely with their classmates and instructors, leading to decreasing their anxiety and increasing their motivation. Further, another line of discussion for the results, as Richter and McPherson (2012) argue, during online learning, the EFL learners might have got access to the learning materials and teachers’ explanations of the key points even after the class. Such an advantage might have assisted the participants to refer back to the materials shared before. Accordingly, they might have corrected the lack in their competencies and consolidated them substantially. This, in turn, may have acted as a positive factor to reduce their anxiety and increase their motivation. Likewise, aligned with DeVaney (2010), it may be argued that as the online learning might have provided a learner-centered setting, paving the way for the participants to learn English more independently, it might have helped them to learn based on their needs and interests. This, accordingly, might have been fruitful for the learners to shape the positive attitudes toward the online learning.

Another line of discussion for the results of the study may be associated with the view that the availability and flexibility of the Skype application might have assisted the learners to boost their motivation and handle their anxiety in doing the tasks and obligations (Bolliger & Halupa, 2012; Yu, 2019). In addition, as Namaziandost et al. (2021) argue, another probable reason for the findings of the study may be attributed to this view that the Skype application might have expanded the learning environment outside of the classroom context. As such, the participants might not have felt anxious not to lose the learning materials presented in the online classes. Moreover, the findings of this research may receive support from the online collaborative learning theory, suggested by Harasim (2012). Along with this theory, it may be argued that the Internet facilities might have created a learning environment through which the learners might have increased the amount of collaboration and knowledge building. According to this theory, it may be argued that the learners might have solved their problems through cooperation with other peers, which might have led to a substantial learning development. Besides, our results may be supported by connectivism (Siemens, 2004). As Kop (2011) argues, knowledge might have been constructed by interactions that occurred in Skype.

Discussion on the second research question

As noted above, the second research question explored if the Iranian EFL learners held positive attitudes toward online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings revealed that the learners shaped positive attitudes toward using online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results may be discussed from this view that the participants might have felt relaxed to express their opinions and ideas in the online learning, leading to shaping the positive attitudes. Furthermore, along with Hashemifardnia et al. (2020), it may be argued that access to online course materials might have been a helpful agent in shaping a favorable attitude toward online learning. Additionally, it might be argued that the learners had more contact with their teachers and peers without time and location limitations in online learning. It might be the other justification for presenting positive attitudes toward online learning. The results of this study lend credence to the findings of Joseph and Nath (2013). They indicated that 66% of the participants expressed a positive attitude toward online learning. Also, the findings of the study lend support to those of Sahli and Bouhass Benaissi (2018), showing that the respondents held positive attitudes toward online instruction to improve writing skills. In addition, our research findings are supported by Cinkara (2013), indicating that their learners had positive attitudes toward online learning in Turkish EFL contexts.

Another potential reason for the participants’ positive attitudes toward online learning might lie in the convenient built-in functions of applications and the portability of digital devices (Yu et al., 2022). The built-in functions are the already available functions in applications and programming languages that are easy to use by the users. Based on the findings, it may be argued that since the participants found the built-in functions easy to use, they might have promoted their learning efficiently. This, in turn, might have acted as a major reason for the learners to shape positive attitudes toward the online learning. Another line of discussion for the findings may be ascribed to the benefits of online learning (Azizi, 2022; Tzankova et al., 2022). In other words, the students might have developed useful skills by using specialized knowledge, creating efficient processes, and making decisions about best communication practices, such as what should be discussed face-to-face or electronically (Adedoyin & Soykan, 2020; Paudel, 2021). These outstanding benefits might have pushed the participants to increase their motivation, control their anxiety, and shape positive attitudes toward online learning.

Conclusion and implications

According to the findings of this study, we can conclude that using online instruction could exert positive effects on English language learning by increasing EFL learners’ motivation and reducing their anxiety. Since we live in an era of information and communication technology, it is evident that education, especially L2 education, is under the effects of it (Namaziandoast et al., 2021; Yu & Hu, 2022). These technological developments have been combined with the advent of multimedia. As time goes on, modern multimedia has evolved in the contexts of online contexts. Accordingly, language teachers are recommended to consider the online environments as valuable resources for enriching and empowering English teaching and learning.

Some implications may be presented for different stakeholders and practitioners in light of the findings of the study. Firstly, the policy-makers in the ministry of education may benefit from the findings of this study to move a part of the education to the virtual environment. They should supply the required infrastructures for this valuable purpose and educate teachers to act professionally in online classes. Secondly, school principals and language institute owners may want to equip their educational centers with new technological devices like computers to let EFL learners take advantage of online classes. Thirdly, EFL learners may gain insight into the effectiveness of online classes to reduce students’ anxiety, increase their motivation, and shape their attitudes positively. To this end, they need to improve their digital literacy such that they can adapt their instruction to the new learning environment. Fourthly, based on the results of the study, materials developers may want to accommodate the net technologies into materials development for EFL learners. In such a way, EFL learners may not be deprived of the advantages of online classes. Finally, in line with the findings of the study, EFL learners should take urgent steps to use online classes to improve their language proficiency. For example, they may want to engage in technological devices, so their digital self-efficacy improves.

An important point must be mentioned here. While this study mostly advocates the advantages of online classes, doubtfully, e-learning always comes with challenges, too (Wang & Derakhshan, 2021; Wang et al., 2022, 2021).

Some limitations were imposed on the present study, which may lay the groundwork for further research for researchers. First, as the current study used a quantitative design, future studies can use qualitative designs to shed light on this topic from other different perspectives. For example, semi-structured interviews can be used to investigate Iranian EFL learners’ perceptions of using online learning to affect their motivation, anxiety, and attitude. Second, as this study selected just male EFL learners, future studies can choose their participants from female EFL learners to increase the generalizability of the findings. Third, since the current study included 200 EFL learners, future studies are needed to incorporate larger samples in other parts of the country to increase the external validity of the results. Fourth, anxiety, motivation, and attitude are complex constructs that may vary from culture to culture. These constructs are also closely associated with individual differences (IDs), therefore some cross-cultural studies in future studies can deepen our understanding in this regard. Last but not least, because this study addressed just motivation, anxiety, and attitude of Iranian EFL learners during the COVID-19 pandemic, interested researchers may explore other affective factors, such as self-efficacy and willingness to communicate.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Abbasi, S., Chalak, A., & Heidari Tabrizi, H. (2020). Effect of online strategies-based instruction on Iranian EFL learners’ speaking scores: A case of affective and social strategies instruction. Journal of Modern Research in English Language Studies, 8(3), 51–71.

Adedoyin, O. B., & Soykan, E. (2020). Covid-19 pandemic and online learning: the challenges and opportunities. Interactive Learning Environments, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1813180.

Ahmed, M., Aftab, M., & Yaqoob, H. (2015). Students’ motivation toward English language learning at undergraduate level. Advances in Language and Literary Studies, 6(3), 1–9.

Ahmed, N., & Elttayef, A. (2016). The impact of utilizing skype as a social tool network community on developing English major students’ discourse competence in the English language syllables. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(11), 29–33.

Ahmed, R., & Al-Kadi, A. (2021). Online and face-to-face peer review in academic writing: Frequency & preferences. Eurasian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 7(1), 169–201. https://doi.org/10.32601/ejal.911245.

Alipour, P., & Ehmke, T. (2020). A comparative study of online vs. blended learning on vocabulary development among intermediate EFL learners. Cogent Education, 7(1), 182–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2020.1857489

Azizi, Z. (2022). A phenomenographic study on university English teachers’ perceptions of online classes during the COVID-19 pandemic: A focus on Iran. Education Research International, 23, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/1368883

Azizi, Z., Rezai, A., Namaziandost, E., & Tilwani, S. A. (2022). The role of computer self-efficacy in high school students’ e-learning anxiety: A mixed-methods study. Contemporary Educational Technology, 14(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.30935/cedtech/11570

Baker, C. (1992). Attitudes and language. Multilingual Matters.

Bal-Taştan, S., Davoudi, S. M. M., Masalimova, A. R., Bersanov, A. S., Kurbanov, R. A., Boiarchuk, A. V., & Pavlushin, A. A. (2018). The Impacts of teacher’s efficacy and motivation on student’s academic achievement in science education among secondary and high school students. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics Science and Technology Education, 14(6), 2353–2366. https://doi.org/10.29333/ejmste/89579

Bolliger, D. U., & Halupa, C. (2012). Student perceptions of satisfaction and anxiety in an online doctoral program. Distance Education, 33(1), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2012.667961

Brown, D. H. (2000). Principles of language learning and teaching. (4th ed.). Longman.

Brown, H. D. (2004). Language assessment: Principles and classroom practices. Longman.

Carrillo, C., & Flores, M. A. (2020). COVID-19 and teacher education: A literature review of online teaching and learning practices. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(4), 466–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1821184

Cinkara, E. (2013). Learners’ attitudes towards online language learning and corresponding success rates. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 14(2), 118–130.

Daly, J. A., & McCroskey, J. C. (1994). Avoiding communication: Shyness, reticence, and communication apprehension. Sage.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1975). Intrinsic motivation. New York Plenum Press.

Derakhshan, A., Kruk, M., Mehdizadeh, M., & Pawlak, M. (2021). Boredom in online classes in the Iranian EFL context: Sources and solutions. System, 101, 102556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102556

DeVaney, T. A. (2010). Anxiety and attitude of graduate students in on-campus vs. online statistics courses. Journal of Statistics Education, 18(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691898.2010.11889472

Dirjal, A., Ghapanchi, Z., & Ghonsooly, B. (2021). The role of skype in developing listening and speaking skills of EFL learners. Multicultural Education, 7(1), 177–190. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4448068

Dörnyei, Z. (1998). Motivation in second and foreign language learning. Language Teaching, 31(3), 117–135. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026144480001315X

Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The psychology of the language learner: Individual Differences in Second Language Acquisition. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Dörnyei, Z. (2011). The psychology of second language acquisition. Oxford University Press.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2013). Teaching and researching: Motivation. Routledge.

Ehrman, M. E., & Oxford, R. L. (1995). Cognition plus: Correlates of language learning success. Modern Language Journal, 79(1), 67–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1995.tb05417.x

Esra, M. E. E., & Sevilen, Ç. (2021). Factors influencing EFL students’ motivation in online learning: A qualitative case study. Journal of Educational Technology and Online Learning, 4(1), 11–22.

Esteves, P. T., Arede, J., Travassos, B., & Dicks, M. (2021). Gaze and shoot: examining the effects of player height and attacker-defender interpersonal distances on gaze behavior and shooting accuracy of elite basketball players. Revista De Psicología Del Deporte (Journal of Sport Psychology), 30(3), 1–8.

Gardner, R. C. (2004). Attitude/motivation test battery: International AMTB research project (English Version). Available from: http://publish.uwo.ca/~gardner/docs/englishamtb.pdf

Gardner, R. (2010). Motivation and second language acquisition the socio-educational model. New York Peter Lang Publishing.

Gardner, R. C., & MacIntyre, P. D. (1991). An instrumental motivation in language study. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 13(1), 57–72. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263100009724

Gradman, H. L., & Hanania, E. (1991). Language learning background factors and ESL proficiency. The Modern Language Journal, 75(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.2307/329833

Haidara, Y. (2016). Psychological factor affecting English speaking performance for the English learners in Indonesia. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 4(7), 1501–1505.

Harasim, L. (2012). Learning theory and online technologies. Routledge/Taylor and Francis.

Harmer, J. (2007). The practice of English language teaching. Longman Pearson Education Limited.

Hartnett, M. (2011). Examining motivation in online distance learning environments: Complex, multifaceted, and situation-dependent. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 12(6), 20–38. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v12i6.1030

Hartnett, M. (2016). The importance of motivation in online learning. In M. Hartnett (Ed.), Motivation in online education (pp. 5–32). Springer.

Hasan, N., & Bao, Y. (2020). Impact of “e-Learning crack-up” perception on psychological distress among college students during COVID-19 pandemic: A mediating role of “fear of academic year loss”. Children and Youth Services Review, 118, 105–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105355

Hashemifardnia, A., Shafiee, S., Rahimi Esfahani, F., & Sepehri, M. (2020). Effects of massive open online course (MOOC) on Iranian EFL learners’ speaking complexity, accuracy, and fluency. Computer-Assisted Language Learning Electronic Journal, 22(1), 56–79.

Hashemifardnia, A., Shafiee, S., Rahimi Esfahani, F., & Sepehri, M. (2021). Effects of flipped instruction on Iranian intermediate EFL learners’ speaking complexity, accuracy, and fluency. Cogent Education, 8(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186x.2021.1987375

Herguner, G., Son, S. B., Son, H., & Donmez, A. (2020). The effect of online learning attitudes of university students on their online learning readiness. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET, 19(4), 102–110.

Hilliard, J., Kear, K., Donelan, H., & Heaney, C. (2020). Students’ experiences of anxiety in an assessed, online, collaborative project. Computers & Education, 143, 103675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103675

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., & Bond, A. (2020). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. EDUCAUSE Review. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergencyremote-teaching-and-onlinelearning. Accessed Jan 2022.

Horwitz, E. K. (1986). Preliminary evidence for the reliability and validity of a foreign language anxiety scale. TESOL Quarterly, 20(3), 559–562. https://doi.org/10.2307/3586302

Horwitz, E. K. (1991). Preliminary evidence for the reliability and validity of a foreign language anxiety scale. In E. K. Horwitz, & D. J. Young (Eds.), Language anxiety: From theory and research to classroom implications (pp. 37–39). Prentice Hall.

Horwitz, E. K. (2001). Language anxiety and achievement. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 21, 112–126. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190501000071

Hosseini, S. B., & Pourmandnia, D. (2013). Language learners’ attitudes and beliefs: Brief review of the related literature and frameworks. International Journal on Trends in Education and Their Implications, 4(4), 77–89.

Hukle, D. R. L. (2009). An evaluation of readiness factors for online education, Mississippi State University, Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, Mississippi.

Joseph, A. M., & Nath, B. (2013). Integration of massive open online education (MOOC) system with in-classroom interaction and assessment and accreditation: An extensive report from a pilot study. In Proceedings of the international conference on e-learning, e-business, enterprise information systems, and e-Government (EEE) (p. 105). The Steering Committee of the World Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering and Applied Computing.

Kim, K. J., & Frick, T. W. (2011). Changes in student motivation during online learning. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 44(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.2190/EC.44.1.a

Kim, T. Y., & Kim, Y. (2021). Structural relationship between L2 learning motivation and resilience and their impact on motivated behavior and L2 proficiency. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 50(2), 417–436. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-020-09721-8

Knouse, S. M., Bessy, M., & Longest, K. C. (2021). Knowing who we teach: Tracking attitudes and expectations of first-year postsecondary language learners. Foreign Language Annals, 54(1), 50–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12510

Kop, R. (2011). The challenges to connectivist learning on open online networks: Learning experiences during a massive open online course. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning. http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/882/1823. Accessed Jan 2022.

Kruger-Ross, M. J., & Waters, R. D. (2013). Predicting online learning success: Applying the situational theory of publics to the virtual classroom. Computers & Education, 61, 176–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.09.015

Lambert, W. E. (1967). A social psychology of bilingualism. Journal of Social Issues, 23(2), 91–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1967.tb00578

Leki, I. (1999). Techniques for reducing second language writing anxiety. In D. J. Youngred Affect in foreign language and second language learning. A practical guide to creating a low-anxiety classroom atmosphere (pp. 64–88). McGraw-Hill.

Li, L. Y., & Tsai, C. C. (2017). Accessing online learning material: Quantitative behavior patterns and their effects on motivation and learning performance. Computers & Education, 114, 286–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.07.007

MacIntyre, P. D. (1988). How does anxiety affect second language learning? A reply to Sparks and Ganschow. The Modern Language Journal, 79(1), 90–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1995.tb05418.x

MacIntyre, P., & Gregersen, T. (2012). Emotions that facilitate language learning: The positive-broadening power of the imagination. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 2(2), 193–213.

Mackey, A., & Gass, S. M. (2015). Second language research: Methodology and design. Routledge.

Madjid, A., & Samsudin, M. (2021). Impact of achievement motivation and transformational leadership on teacher performance mediated by organizational commitment. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 21(3), 107–119. https://doi.org/10.12738/jestp.2021.3.008

Mahyoob, M. (2020). Challenges of e-Learning during the COVID-19 pandemic experienced by EFL learners. Arab World English Journal (AWEJ), 11(4), 351–362.

Mayadas, A. F., Bourne, J., & Bacsich, P. (2009). Online education today. Science, 3, 85–89.

Melhe, M. A., Salah, B. M., & Hayajneh, W. S. (2021). Impact of training on positive thinking for improving psychological hardiness and reducing academic stresses among academically-late students. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 21(1), 132–146. https://doi.org/10.12738/jestp.2021.3.010

Meşe, E., & Sevilen, Ç. (2021). Factors influencing EFL students’ motivation in online learning: A qualitative case study. Journal of Educational Technology & Online Learning, 4(1), 11–22.

Mohammadimehr, M. (2020). Letter to the editor: E-learning as an educational response to COVID-19 epidemic in Iran: The role of the learner support system. Future of Medical Education Journal, 10(3), 64–65.

Montero, R. P., Chaves, M. J. Q., & Alvarado, J. S. (2014). Social factors involved in second language learning: a case study from pacific campus, Universidad de costa Rica. Revista De Lenguas Modernas, 2, 44–60.

Moore, M. G., & Kearsley, G. (2011). Distance education: A systems view of online learning (What’s new in education?) (3rd ed.). Cengage Learning.

Moskowitz, S., & Dewaele, J. M. (2021). Is teacher happiness contagious? A study of the link between perceptions of language teacher happiness and student attitudes. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 15(2), 117–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2019.1707205

Moşteanu, N. R. (2021). Teaching and learning techniques for the online environment. how to maintain students’ attention and achieve learning outcomes in a virtual environment using new technology. International Journal of Innovative Research and Scientific Studies, 4(4), 278–290. https://doi.org/10.53894/ijirss.v4i4.298

Murphy, M. P. A. (2020). COVID-19 and emergency e-Learning: Consequences of the securitization of higher education for post-pandemic pedagogy. Contemporary Security Policy, 41(3), 492–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2020.1761749

Namaziandost, E., Hashemifardnia, A., Bilyalova, A., Fuster-Guillén, D., Garay, P., Ngoc Diep, J. P., Ismail, L. T., Sundeeva, H., & Rivera-Lozada, O. (2021). The effect of WeChat-based online instruction on EFL learners’ vocabulary knowledge. Education Research International, 2, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8825450

Namaziandost, E., Razmi, M. H., Hernández, R. M., Ocaña-Fernández, Y., & Khabir, M. (2022a). Synchronous CMC text chat versus synchronous CMC voice chat: impacts on EFL learners’ oral proficiency and anxiety. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54(4), 599–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1906362

Namaziandost, E., Razmi, M. H., Tilwani, S. A., & Pourhosein Gilakjani, A. (2022b). The impact of authentic materials on reading comprehension, motivation, and anxiety among Iranian male EFL learners. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 38(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2021.1892001

O’malley, J. M., & Chamot, A. U. (1990). Learning strategies in second language acquisition. Cambridge University Press.

Oxford, R. (1999). Anxiety and the language learner new insights. In J. Arnold (Ed.), Affect in Language Learning (pp. 58–67). Cambridge University Press.

Özhan, ŞÇ, & Kocadere, S. A. (2020). The effects of flow, emotional engagement, and motivation on success in a gamified online learning environment. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 57(8), 2006–2031.

Pallant, J. (2020). SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using IBM SPSS. Routledge.

Paudel, P. (2021). Online education: Benefits, challenges and strategies during and after COVID-19 in higher education. International Journal on Studies in Education, 3(2), 70–85.

Pawlak, M., Derakhshan, A., Mehdizadeh, M., & Kruk, M. (2021). The effects of class mode, course type, and focus on coping strategies in the experience of boredom in online English language classes. Language Teaching Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211064944

Peng, X., Liang, S., Liu, L., Cai, C., Chen, J., Huang, A., & Zhao, J. (2022). Prevalence and associated factors of depression, anxiety and suicidality among Chinese high school E-learning students during the COVID-19 lockdown. Current Psychology, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02512-x.

Phillips, E. (1999). Decreasing language anxiety: Practical techniques for oral activities. In D. J. Young (Ed.), Affect in foreign language and second language learning. A practical guide to creating a low-anxiety classroom atmosphere (pp. 124–143). McGraw-Hill.

Qinghua, Z. (2021). Evaluation and prediction of sports health literacy of college students based on artificial neural network. Revista De Psicología Del Deporte (Journal of Sport Psychology), 30(3), 9–18.

Qureshi, H., Javed, F., & Baig, S. (2020). The effect of psychological factors on English speaking performance of students enrolled in postgraduate English language teaching. Global Language Review, 5(2), 101–114. https://doi.org/10.31703/glr.2020(V-II).11

Rahimi, M., & Fathi, J. (2021). Exploring the impact of wiki-mediated collaborative writing on EFL students’ writing performance, writing self-regulation, and writing self-efficacy: A mixed methods study. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 3, 1–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2021.1888753

Rahimi, S., Ghonsooly, B., & Rezai, A. (2021). An online portfolio assessment and perception study of Iranian high school students’ english writing performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Teaching English as a Second Language (Formerly Journal of Teaching Language Skills), 40(3), 197–231. https://doi.org/10.22099/jtls.2021.39788.2946

Rapanta, C., Botturi, L., Goodyear, P., Guàrdia, L., & Koole, M. (2020). Online university teaching during and after the Covid-19 crisis: Refocusing teacher presence and learning activity. Post-digital Science and Education, 7, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00155-y

Razmjou, G. (2021). The effectiveness of online language learning during the pandemic from the perspective of some Iranian EFL learners. International Journal of Pedagogical Advances in Technology-Mediated Education, 2(1), 39–45.

Reid, M. J. (1995). Learning styles in the ESL/EFL classroom. Heinle & Heinle.

Riazi, A. M. (2016). The Routledge encyclopedia of research methods in applied linguistics. Routledge.

Richter, T., & McPherson, M. A. (2012). Open educational resources: Education for the world? Distance Education, 3(2), 201–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2012.692068

Riding, R., & Cheema, I. (1991). Cognitive styles-an overview and integration. Educational Psychology, 11(3–4), 193–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144341910110301

Ryan, R., & Deci, E. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

Sahli, N., & Bouhass Benaissi, F. (2018). Integrating massive open online courses in teaching research and writing skills. International Journal of Social Sciences and Educational Studies, 5(2), 231–240.

Sahu, P. (2020). Closure of universities due to Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Impact on education and mental health of students and academic staff. Cureus, 12(4), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7541

Saito, Y., Horwitz, E. K., & Garza, M. (1999). Foreign language reading anxiety. Modern Language Journal, 83, 202–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/0026-7902.00016

Sara, G., Shah, I., Burgoyne, J., Nazri, M., & Salleh, J. R. (2017). The influence of motivation on job performance: A case study at Universiti Teknologi Malaysia. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 11(4), 92–99.

Shafiee Rad, H., Namaziandost, E., & Razmi, M. H. (2022). Integrating STAD and flipped learning in expository writing skills: Impacts on students’ achievement and perceptions, Journal of Research on Technology in Education, (in press), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2022.2030265

Shahidi, S. (2020). Comparing the effectiveness of conventional and Kano model questionnaire for gathering requirement of online bus reservation system. International Journal of Innovative Research and Scientific Studies, 3(1), 27–32. https://doi.org/10.53894/ijirss.v3i1.30

Siemens, G. (2004). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 2, 1–9.

Song, S. H. (2000). Research issues of motivation in Web-based instruction. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 1(3), 225–229.

Steers, R. M., & Porter, L. W. (Eds.). (1991). Motivation and work behavior (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Sudina, E., & Plonsky, L. (2021). Language learning grit, achievement, and anxiety among L2 and L3 learners in Russia. ITL-International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 172(2), 161–198. https://doi.org/10.1075/itl.20001.sud

Tabachnick, B. G., Fidell, L. S., & Ullman, J. B. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (Vol. 5). Pearson.

Tahmouresi, S., & Papi, M. (2021). Future selves, enjoyment and anxiety as predictors of L2 writing achievement. Journal of Second Language Writing, 53, 100837. https://doi.org/10.1075/itl.20001.sud

Tallon, M. (2009). Foreign language anxiety and heritage students of Spanish: A quantitative study. International Journal of Higher Education, 42(1), 112–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2009.01011.x

Tejada Reyes (2019). Factors that influence basic level English language learning Unpublished thesis at the Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo Centro UASD.

Terantino, J. (2014). Skype videoconferencing for less commonly taught languages: Examining the effects on students’ foreign language anxiety. International Association for Language Learning Technology Journal, 3(4), 56–69.

Tsunemoto, A., & McDonough, K. (2021). Exploring Japanese EFL learners’ attitudes toward English pronunciation and its relationship to perceived accentedness. Language and Speech, 64(1), 24–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0023830919900372

Tuan, L. (2012). An empirical research into EFL learners’ motivation. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 2, 430–439.

Tzankova, I., Compare, C., Marzana, D., Guarino, A., Di Napoli, I., Rochira, A., & Albanesi, C. (2022). Emergency online school learning during COVID-19 lockdown: A qualitative study of adolescents’ experiences in Italy. Current Psychology, (In Press), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02674-8

Usta, E. (2011). The effect of web-based learning environments on attitudes of students regarding computer and internet. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 28, 262–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.051

Vogely, A. (1999). Addressing listening comprehension anxiety. In D. J. Young (Ed.), Affect in foreign language and second language learning. A practical guide to creating a low-anxiety classroom atmosphere (pp. 106–123). McGraw-Hill.

Wang, Y. L., & Derakhshan, A. (2021). A Book review on “Investigating dynamic relationship among ındividual difference variables in learning english as a foreign language in a virtual world”. System, 100, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102531

Wang, Y., Derakhshan, A., & Pan, Z. (2022). Positioning an agenda on a loving pedagogy in SLA: Conceptualization, practice and research. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.894190

Wang, Y., Derakhshan, A., & Zhang, L. J. (2021). Researching and practicing positive psychology in second/foreign language learning and teaching: The past, current status and future directions. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.731721

Wang, Y. L., & Guan, H. F. (2020). Exploring demotivation factors of Chinese learners of English as a foreign language based on positive psychology. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, 29, 851–861. https://doi.org/10.24205/03276716.2020.116

Weinburgh, M. H. (2000). Gender, ethnicity, and grade level as predictors of middle school students’ attitudes toward science. Current Issues in Middle Level Education, 143, 72–84.

Williams, M., & Burden, R. (1997). Psychology for language teachers: A social constructivist approach. Cambridge University Press.

Wolfinger, S. (2016). An exploratory case study of middle school student academic achievement in a fully online virtual school Doctoral dissertation, Drexel University, The United States of America.

Young, D. J. (1992). Creating a low-anxiety classroom environment: What does language anxiety research suggest? The Modern Language Journal, 75, 426–439. https://doi.org/10.2307/329492

Young, D. J. (1994). New directions in language anxiety research. In C. A. Klee (Ed.), Faces in a crowd: The individual learner in multi-section courses (pp. 3–46). Heinle & Heinle.

Young, D. J. (1999). Affect in foreign language and second language learning. A practical guide to creating a low-anxiety classroom atmosphere. McGraw-Hill.

Yu, A. Q. (2019). Understanding information technology acceptance and effectiveness in college students’ English learning in China. Doctoral dissertation, University of Nebraska, Nebraska, America.

Yu, H., & Hu, J. (2022). A multilevel regression analysis of computer-mediated communication in synchronous and asynchronous contexts and digital reading achievement in Japanese students. Interactive Learning Environments, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2022.2066136

Yu, J., Zhou, X., Yang, X., & Hu, J. (2022). Mobile-assisted or paper-based? The influence of the reading medium on the reading comprehension of English as a foreign language. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(1–2), 217–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2021.2012200

Zhang, L. J. (2001). Exploring variability in language anxiety: Two groups of PRC students learning ESL in Singapore. RELC Journal, 32(1), 73–94.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1 Attitude towards Online Learning Questionnaire

Appendix 1 Attitude towards Online Learning Questionnaire

(1) Strongly Disagree, (2) Disagree, (3) Neither agree nor disagree, (4) Agree, (5) Strongly Agree

1. Online classes help me regulate my learning. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

2. I can save a lot of time by taking online classes. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

3. Online courses offer a variety of learning opportunities. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

4. I find the materials used in online courses more accessible than in face-to-face courses. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

5. Online learning provides easy access to search engines, note-taking apps, and online dictionaries, learning tools, etc. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

6. In an online course, it’s quite easy to get in touch with my classmates. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

7. I feel less stress and anxiety in online classes than in face-to-face classes. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

8. In the online course, I can easily ask the teacher questions that I encounter during class. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

9. Online learning is a great alternative to face-to-face learning in the event of incidents like COVID-19, bad weather, or other unexpected problems. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

10. The teacher can provide enough feedback in an online course. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

11. The assignments are carefully checked in the online courses. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

12. Working with partners and interacting with learners is easy in an online course. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

13. (R) Online classes are less motivating than face-to-face classes. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

14. Online learning gives both teachers and students easy access to educational materials, including multimedia and presentation tools. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

15. (R) I think online classes are of lower quality than face-to-face classes. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

16. I think online courses reduce distractions and increase focus. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

17. I find online classes more enjoyable than face-to-face classes. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

18. (R) I believe that learning a language online is less effective than a real face-to-face lesson. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

19. Online courses provide easier ways of learning new languages. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

20. (R) I believe that teachers and learners are not yet ready for online learning due to online infrastructure and facilities as well as lack of sufficient instructions. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, P., Namaziandost, E., Azizi, Z. et al. Exploring the effects of online learning on EFL learners’ motivation, anxiety, and attitudes during the COVID-19 pandemic: a focus on Iran. Curr Psychol 42, 2310–2324 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-04013-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-04013-x