Abstract

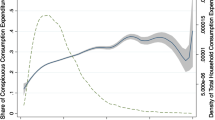

The standard of living of persons and households is not only a matter of income, but ultimately depends on the level and quality of their consumption in terms of goods and services purchased. Consumption expenditures can be regarded as the result of decisions based on the demand, preferences and limited economic resources, and are thus manifestations not only of different lifestyles, but also of inequality, affluence and deprivation. But how are different levels and kinds of consumption related to subjective well-being (SWB)? While the relationship between income and SWB has been explored in numerous studies, surprisingly little is known as yet about the association between consumption expenditures and SWB. Referring to theoretical considerations and previous research, this article focuses on the empirical analysis of how and to what extent SWB—in terms of life satisfaction—is affected by the level and structure of consumption expenditures in German households. The analysis is based on the data from the German Socio-Economic Panel Study, which for the first time in 2010 included a module on consumption expenditures. The results of our analysis demonstrate that life satisfaction increases with increasing consumption expenditures, but the findings also suggest that persons in the lowest decile of consumption expenditures turn out to be less unsatisfied with their lives than persons in the lowest income decile. Moreover, our research provides evidence to suggest that low levels of spending resulting from voluntary decisions do not reduce life satisfaction at all. Finally, the paper also points out the ways in which SWB is affected by particular kinds of consumption expenditures. It appears that expenditures on clothing and leisure are drivers of SWB, while expenditures on food and housing—which may be considered more demand driven—do not affect life satisfaction significantly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

SWB may, however, also be directly affected by unspent income, e.g., if income as such provides options, security and social prestige, or the prospect of future consumption.

For more details, see (Headey et al. 2004: 9).

More generally, this means that “current-out-of-pocket expenditures may therefore provide an inaccurate picture of the service flow provided by a consumer unit’s stock of consumer durables…, spending on new automobiles is included in expenditures, but the consumption value of the existing stock is not” (Cutler and Katz 1991: 32).

The SOEP is a representative longitudinal study of private households and individuals within households, which is carried out by the German Institute for Economic Research, DIW Berlin. This annual survey currently has a sample size of almost 11,000 households, and around 30,000 persons. For more information on the SOEP, see www.diw.de/en/soep; detailed data documentation information is available at www.diw.de/en/diw_02.c.221180.en/research_data_center_soep.html (accessed October 6, 2014).

For more information on the German Income and Consumption Survey, see Statistisches Bundesamt (2013).

Although the SOEP employed different approaches to collecting housing expenditures, the single-expenditure items were combined to give a total level of housing expenditure according to the taxonomy used in the official Income and Expenditure Survey. Accordingly, expenditures relating to modernization work which increases the financial value of buildings are not considered as consumption, but rather investment. In calculating the housing expenditures of home owners, no “imputed rent” has been taken into account.

For more detailed information, see Becker et al. (2002).

See Noll and Weick (2007) for a more detailed analysis of the issue of “overspending.”

In each of the regression models, both consumption expenditures and household income are treated as logarithmized variables both due to the expected nonlinear relationships and in order to normalize the skewed income and expenditure distributions. Logarithmizing income—and analogously consumption expenditures—as predictors of life satisfaction in regression models seems to represent the current state of the art. See, e.g., Van Praag and Ferrer-I-Carbonell (2008).

Using percentages of the total expenditure rather than the absolute amounts spent in diverse categories of goods and services produced similar results overall. See Noll and Weick (2014: 5).

The observation of a decrease in the proportion of the total expenditure that is spent on nutrition with increasing household income goes back to the studies of the German statistician Ernst Engel in the nineteenth century and is thus also referred to as “Engel's law.”

Available empirical evidence also suggests a positive association between luxury consumption and SWB. See Hudders and Pandelaere (2012).

References

Ackerman F (1997) Consumed in theory: alternative perspectives on the economics of consumption. J Econ Issues 31(3):651–664

Ahuvia AC (2002) Individualism/collectivism and cultures of happiness: a theoretical conjecture on the relationship between consumption, culture and subjective well-being at the national level. J Happiness Stud 3:23–36

Andrews FM, McKennell AC (1980) Measures of self-reported well-being: their affective, cognitive, and other components. Soc Indic Res 8:127–155

Atkinson AB (1998) Poverty in Europe. Blackwell, Oxford

Becker I, Frick J, Grabka MM, Hauser R, Krause P, Wagner GW (2002) A comparison of the main household income surveys for germany: EVS and SOEP. In: Hauser R, Becker I (eds) Reporting on income distribution and poverty. Perspectives from a German and a European point of view. Springer, Heidelberg, pp 55–90

Biswas-Diener R (2008) Material wealth and subjective well-being. In: Eid M, Larsen RJ (eds) The science of subjective well-being. Guilford, New York, pp 307–322

Charles KK, Danziger S, Li G, Schoeni RF (2007) Studying consumption with the panel study of income dynamics: comparisons with the consumer expenditure survey and an application to the intergenerational transmission of well-being. finance and economic discussion series 2007–2016. Divisions of research and statistics and monetary affairs. Federal Reserve Board, Washington, DC

Cutler DM, Katz LF (1991) Macroeconomic performance and the disadvantaged. Brook Pap Econ Act 1(2):1–74

DeLeire T, Kalil A (2010) Does consumption buy happiness? Evidence from the United States. Int Rev Econ 57:163–176

Diener E, Sandvik E, Seidlitz L, Diener M (1993) The relationship between income and subjective well-being: relative or absolute? Soc Indic Res 28:195–223

Duesenberry JS (1949) Income, saving, and the theory of consumer behavior. Harvard University, Cambridge

Easterlin R (2004) Diminishing marginal utility of income? A caveat. University of Southern California, Law and Economics working paper series, No. 5. Los Angeles

Guillen-Royo M (2007) Well-being and consumption: towards a theoretical approach based on human needs satisfaction. In: Bruni L, Porta PL (eds) Handbook on the economics of happiness. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 151–169

Headey B, Muffels R, Wooden M (2004) Money doesn’t buy happiness… or does it? A reconsideration based on the combined effects of wealth, income and consumption. IZA Discussion Paper No. 1218. Bonn

Hudders L, Pandelaere M (2012) The silver lining of materialism: the impact of luxury consumption on subjective well-being. J Happiness Stud 13:411–437

Lewis J (2014) Income, expenditure and personal well-being, 2011/12. Research report, UK Office for National Statistics. Newport, South Wales (www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171766_365207.pdf; accessed Oct. 6, 2014)

MacDonald M, Douthitt RA (1992) Consumption theories and consumer’s assessments of subjective well-being. J Consum Aff 26(2):243–261

Marcus J, Siegers R, Grabka MM (2013) Preparation of data from the new SOEP consumption module. Editing, imputation, and smoothing. Data documentation 70. Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung, Berlin

Meyer B, Sullivan J (2006) Three decades of consumption and income poverty. National poverty center working paper series, No. 06-35. University of Michigan, September 2006 (www.npc.umich.edu/publications/working_papers/; accessed Oct. 6, 2014)

Noll H-H (2007) Household consumption, household incomes and living standards. A review of related recent research activities. GESIS, Mannheim. Published online only (www.gesis.org/fileadmin/upload/institut/wiss_arbeitsbereiche/soz_indikatoren/Publikationen/Household-Expenditures-Research-Report.pdf)

Noll H-H, Weick S (2005) Markante Unterschiede in den Verbrauchsstrukturen verschiedener Einkommens-positionen trotz Konvergenz. Analysen zu Ungleichheit und Strukturwandel des Konsums. Informationsdienst Soziale Indikatoren (ISI) 34:1–5

Noll H-H, Weick S (2007) Einkommensarmut und Konsumarmut—unterschiedliche Perspektiven und Diagnosen. Analysen zum Vergleich der Ungleichheit von Einkommen und Konsumausgaben. Informationsdienst Soziale Indikatoren (ISI) 37:1–6

Noll H-H, Weick S (2010) Subjective well-being in Germany: evolutions, determinants and policy implications. In: Greve B (ed) Happiness and social policy in Europe. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 70–88

Noll H-H, Weick S (2014) Lebenszufriedenheit steigt mit der Höhe der Konsumausgaben. Analysen zur Struktur von Konsumausgaben und subjektivem Wohlbefinden. Informationsdienst Soziale Indikatoren (ISI) 51:1–6

Perez-Truglia R (2013) A test of the conspicuous–consumption model using subjective well-being data. J Soc Econ 45:146–154

Slesnick DT (2001) Consumption and social welfare. Living standards and their distribution in the United States. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Statistisches Bundesamt (2013) Fachserie 15, Heft 7. Wirtschaftsrechnungen. Einkommens- und Verbrauchsstichprobe. Aufgabe, Methode und Durchführung. Wiesbaden

Stevenson B, Wolfers J (2013) Subjective well-being and income: is there any evidence of satiation? Am Econ Rev 103(3):598–604

Van Praag B, Ferrer-I-Carbonell A (2008) Happiness quantified. A satisfaction calculus approach. Revised edition. Oxford University, Oxford

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Noll, HH., Weick, S. Consumption expenditures and subjective well-being: empirical evidence from Germany. Int Rev Econ 62, 101–119 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-014-0219-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-014-0219-3

Keywords

- Consumption

- Consumption expenditures

- Household income

- Household expenditures

- Subjective well-being

- Life satisfaction