Abstract

The Chinese Communist Party has recently acknowledged its attempts to bolster good governance by outsourcing public and social service functions to social organizations—non-profit organizations, either created by relevant government bureaus, developed through non-profit incubators, or voluntarily created civil society groups. Do these services gender political trust for the party-state? Using matching methods on an original survey data collected in communities in Shanghai, this article reveals two important findings. (1) Service efficacy—the internal belief that one can affect the content of the services show strong correlation with political trust and the relationship is stronger than that between service quality and political support. (2) There is strong evidence for credit transfer—whilst accountability for these services is attributed to grassroots actors and there is strong correlation between service efficacy and political support, political support increases only for the central government level. The results show how the new programs of social service outsourcing and incorporation of non-governmental organizations in service provision can increase support for the party-state.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has recently acknowledged its attempts to bolster good governance by outsourcing public and social service functions to social organizations. These are non-profit organizations, either created by relevant government bureaus, developed through non-profit incubators, or voluntarily created by civil society groups.Footnote 1 Do these services affect citizens’ political support? While the state may have various motives for adopting this policy, I used survey data I gathered in Shanghai to test whether the provision of these services by social service organizations has an impact on political support for the state by comparing responses between service recipients and non-recipients.

Prior works on sources of regime support in China have found evidence for both performance legitimacy and procedural legitimacy. Performance legitimacy refers to legitimacy that stems from outputs from the political system, such as government performance and effectiveness. Procedural legitimacy refers to legitimacy that stems from inputs, such as citizens’ demands, votes, and interests (Easton 1975). Following these concepts, it has been found that performance legitimacy, such as economic performance, are sources of regime support in China. At the same time, scholars have begun to acknowledge that although the participatory channels differ between China and democracies, citizens’ experiences of input in institutions, such as participating in participatory channels and discursive experiences are also sources of regime support (Truex 2017; Birney 2017). The findings in this paper also offer support for the argument that procedural legitimacy is relevant for explaining political support in China by examining service provision by non-state entities, with a focus on social service organizations. While the level of satisfaction was positively correlated with political trust among service recipients, service efficacy—the internal belief that one can affect the content of services—was a stronger predictor of political trust compared to service satisfaction.

More broadly, the findings in this paper shed new light on the relationship between non-state services and political trust. Existing work on non-state services has shown that when these fill a role of the state that is perceived to be primary, such as health care, such actions may decrease trust in the state (Cammet et al. 2015). This implies that the state loses credit by relying on non-state sources. However, as I will show below, in areas such as urban China, where non-state services do not compete with core services and compensate for the role of the state, there is rather an opposite result: the state gains credit. I argue that when service recipients perceive that grassroots administrations and social service organizations are accountable for the services provided, the state gains trust. I describe this finding about trust as a credit transfer.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. First, I introduce the emergence of the policy related to the government purchase of services from social organizations, and the subsequent efforts of the party-state to develop this system. These efforts include nurturing and developing social organizations, as well as urging mass organizations to innovate and increase the quality of services through the purchase of services from social organizations. A key point about this new system is that there are mechanisms of political control over these organizations, which enables the party-state to promote their growth while thwarting bottom-up contention. Second, I discuss existing research that links non-state services and support for the state. Third, deriving from this previous literature, I hypothesize that services provided by these organizations can affect citizens’ support for the state through the two mechanisms of performance legitimacy and procedural legitimacy. Fourth, I introduce the research design that tests the hypotheses. Lastly, I discuss the findings.

2 Provision of Public Goods by Non-state Entities

Provision of public and social services by non-state entities, such as non-profits and business entities, has become a general practice in many countries. In the developing world, with weak state capacities, this method has been adopted to compensate for a lack of public welfare and infrastructure.Footnote 2 In advanced democracies, reliance on civil society groups and the non-state sector for service provision has risen in tandem with the introduction of new managerial practices in public administration,Footnote 3 which emphasize increasing efficiency in the public sector through outsourcing. China has not been an exception to this trend. Despite media reports of crackdowns on civil society groups that are deemed antagonistic to the regime, there has been increased infrastructural support for service-oriented non-profits, as well as institutionalization of contractual relationships between the state and social groups. This development has been conspicuous both in the public service sector, which was originally monopolized by public service organizations (shiyedanwei), and the social service sector.

Since contracting out was first suggested by economists advocating public choice, the conventional explanation for the motivation of a government to contract out is to enhance efficiency because it implies transferring service production away from a public-sector monopoly to multiple providers who compete for contracts. Other arguments, stemming from a more political economy framework, have examined the effect of party ideology on the adoption of outsourcing.Footnote 4

Although the existing literature offers some insights for understanding government motivations for contracting out in advanced democracies, such arguments do not explain why China, a non-democratic, one-party state, has institutionalized outsourcing of services to non-state entities. I turn to the reasons below.

3 How China Uses Social Forces for Social Service Provision

For China, the time point which marks the initiation of the party-state contracting with non-state entities in public and social service provision can be traced back to the Third Plenum of the 16th Party Congress in 2004, when social organizations, volunteers, and community organizations, broadly termed “social forces” (shehuililiang), were emphasized as important actors of social management (shehuiguanli). Social management, when interpreted in the CCP rhetoric, is the management of society that helps the government resolve tensions, conflicts, and dislocations caused by the market economy (Pieke 2012). The term social management reappears later in the 2011 12th Five-Year Plan and is set as one of the eight key targets, with an emphasis on community service as well as promoting the role of autonomous social organizations in resolving social tensions and increasing public welfare. The way scholars have described this shift varies, from consultative authoritarianism (Teets 2014) to a neo-socialist transformation project of technocratic administrative reform (Pieke 2012).

The party-state’s goal to depoliticize civil society is also reflected in the decision in 2016 to adopt the term ‘social service organizations’ (shehuifuwujigou) to replace the previous regulatory terms ‘non-profit enterprises’ and ‘non-governmental organizations’ (NGOs). These changes have also been accompanied with lowering restrictions for registrations for a sub-set of service organizations, which includes community service and public welfare, as well as increasing the purchase of social services from social service organizations.

Three points can be made about the party-state’s goals from a reading of the Ministry of Civil Affairs’ (MOCA) policy documents on how and why China has institutionalized the outsourcing of services. First, the motivation is to expand the scope of services as well as to create a more demand-oriented framework for service provision. The repeated logic behind the MOCA papers is apparent from the phrase ‘small government, big society (xiaozhengfu, dashehui)’,Footnote 5 which aims to effectively utilize the society to resolve its own problems. This connotation not only includes the idea that the society should replace a part of the pre-existing functions delivered by the state, but the content of services should be co-produced. Institutions such as venture philanthropy (gongyichuangtoubiao)Footnote 6 or government procurement platforms, a system through which MOCA selects programs designed by non-profits, reflect the will of the party-state to accept such deliberations subject to government scrutiny.Footnote 7 At the same time, party organizations are involved in designing their own programs targeted at their constituents.

Another motivation, along with expanding the scope, is to increase the overall quality of the services that are provided. The Chinese public service system has long been monopolized by the public service units (shiyedanwei), which have been criticized for their low quality and low economic efficiency, stemming from bureaucratic configurations established during the planned economy era (Li 2015). Several attempts at reform are underway, including categorizing public service units as well as transforming public service units into non-profits and enterprises.Footnote 8 Government purchase of services is another dimension of these efforts, which aim to increase resource efficiency and quality through contracting and quasi-competition. According to the provision on government purchase of services, the target of purchases is not only limited to social services, but also includes general public services, where enterprises and public service units can participate in bidding.Footnote 9

The third motivation for institutional outsourcing is to increase grassroots governance in urban areas. The background of this impetus is China’s rapid transition from a planned economy to a ‘socialist market economy’, the consequent erosion of the work unit (danwei) system, and subsequent attempts to create communities (shequ). Where state-owned enterprises have closed, the work unit becomes irrelevant as the organizational base of the party and as a delivery mechanism for social services. The erosion of the work unit has led to an increase in the population over which the party no longer has control. Facing these new challenges, MOCA has promulgated the idea of constructing communities (shequ) and developing community services to resolve tensions that rise from urbanization.Footnote 10 It is in this light that social organizations—either community-grown or professional—are encouraged to provide services at the community level. Thus, it is not surprising that social organizations are comprised of those that offer public and social welfare services, but also those that pertain to community-level services.Footnote 11

Before examining the impact of these services on the citizens to ascertain whether the party-state is succeeding in achieving its policy motives in promoting social organizations or non-governmental organizations to strengthen governance, I first address the question of why the party-state trusts NGOs.

4 Mechanisms of Control

I should make clear from the start that despite the party-state’s seemingly open attitude towards voluntary forces, it maintains strong political control over these groups and organizations. These mechanisms enable the party-state to promote the growth of these organizations while thwarting bottom-up contention. There are two formal mechanisms of control: registration and party cells.

Registration status is a difficult qualification to acquire. It is the most important criteria that determines whether organizations can participate in outsourcing or establish any collaborative arrangement with party-state bureaus. The provision on government purchase of services only allows registered organizations to participate, which systematically excludes all those that are not under government control. Registration is also a sign of trustworthiness when an organization’s staff interact with government officials. As one staff member of a grassroots organization that specializes in disabled children’s education commented, “we are registered, and that proves how trustworthy (kaopu) we are”.Footnote 12 Not only is registration difficult to obtain, but it can be rejected based on the titles of organizations and their service content.Footnote 13 Often, organization leaders use their social ties to find a supervisory organization,Footnote 14 which is a criterion to becoming registered.Footnote 15 If lacking social ties, leaders need to continuously signal to the district MOCA bureau that they have good intentions.Footnote 16 Recent guidelines suggest that establishing party cells in the organizationsFootnote 17 signals the party’s willingness to maintain control yet simultaneously continue with collaboration and outsourcing.

Due to the difficulty grassroots organizations face in becoming registered, government-organized non-governmental organizations (GONGOs) still dominate the NGO scene. According to recent research based on randomly sampled organizations in Shanghai on the background of those establishing NGOs, approximately 25% came from a non-governmental background, while the rest had a government background, such as public employees, retired public employees, or those holding dual positions within public service organizations (Guan and Xia 2016).

5 Social Service Organizations in China

5.1 Government Purchase of Services

To initiate the government’s purchase of services, the Ministry of Finances invested approximately 200 million Yuan of designated funds (zhuanxiangzizjin)Footnote 18 in 2012, and announced the fields that would be supported for such purchases. These were then announced by MOCA bureaus at each level. Social organizations that wanted to compete were instructed to send their program applications to their respective MOCA bureau for selection.

In 2016, the Ministry of Civil Affairs announced five main fields, including elderly services, children’s services, disabled services, social work (covering services for the migrant population, children, and adolescents, disabled, low-income population, etc.), and development of the skills of social organizations. After receiving applications, the final providers were selected by third-party entities such as research centers or a committee created by the MOCA.

Purchase of services from social organizations not only occurs at the central level, but at all levels, including city, district, and the neighborhood. The budget mainly comes from three sources: first, special funds (zhuanxiangzijin) delivered to lower levels in the form of fiscal transfers; second, within-budgetary funds (yusuanneizijin), and lastly, extra-budgetary funds (yusuanwaizijin). District levels have also created designated funds for government purchases from social organizations. In Shanghai, four districts comprising Hongkou, Jingan, Minhang, and Songjiang, as well as neighborhood committees have established special funds strictly for purchasing services from social organizations.Footnote 19 The majority of the organizations, when chosen to provide services, limit their target population to the neighborhood.Footnote 20

The process through which services are outsourced at the city, district, and neighborhood levels bears similarities with the process at the central level. Distribution of government funds for purchasing services from non-profits follows the rules of the project system (xiangmuzhi),Footnote 21 whereby funds are released and implementation is monitored according to a detailed project plan. First, an itemized listFootnote 22 of services the government intends to purchase is released, after which applications are submitted by social organizations, and the purchasing bodies select the providers.

The government purchase institutions also include institutions for quality control. The core question that arises regarding the purchase of services is whether the provider becomes accountable for the services they provide. To resolve problems, the central government and the local governments have increasingly relied on the project system (xiangmuzhi) to strengthen accountability. Currently, three institutions mark quality control at particular stages. First, at the selection of providers before the project is implemented, second, in the phased disbursement of project fees (fenqizhifu) to service providers and, third, during the evaluation process that occurs during and after the project’s implementation period.

Albeit there is regional variation in the management of the two processes, purchasing bodies create committees for selection and evaluation, or often designate enterprises or a bureau to be responsible for the process. For instance, a few districts in Shanghai have established a Committee for Government Purchase of Services from Social Organizations, composed of members from the Social Construction bureau, MOCA, and the Finance bureau.Footnote 23 In addition to the selection and evaluation process, the phased disbursement of project fees also serves as a monitoring mechanism, whereby mid-process evaluations are performed prior to the disbursement. The final evaluation occurs after the project’s implementation, whereby the process is conducted either by the purchasing entity or a third-party to whom the purchasing entity delegates the assessment work.

5.2 Incubating Non-profits

Apart from institutionalizing government purchase procedures, another development is that the party-state has also been promoting ways to develop social organizations. Part of the reason can be traced to the fact that there is lack of organizations in China from which government sectors could purchase services (Han 2011).Footnote 24 In the document released by MOCA and the National Development and Reform Commission in 2011 entitled “Announcements on 12th Five-Year Plan on Development of Civil Affairs”, it is mentioned that there will be a focus on the development of philanthropic, public welfare, and community service organizations. The document also establishes the creation of social organization incubators (shehuizuzhifuhuajidi) at different levels.

Although there is wide variation across regions, and even within a district, the incubation process at the community level typically includes active engagement of the residents’ committee, where active party cadres or groups of community residents are mobilized by the residents’ committee to form service organizations.Footnote 25 For instance, one incubation center adjacent to the residents’ committee building in one neighborhood in Shanghai oversaw mobilizing residents, offered offices to organizations, and allowed organizations to devise program applications. Organizations were then encouraged to bid for both district, city, and national level government procurement bids, not limited to their respective district.Footnote 26 At the district level, the focus is wider than community services, and ranges from topics such as environmental conservation to social work. As one incubator program director described, organization leaders are chosen based on their previous experience in public welfare work.Footnote 27 Although MOCA does not strictly determine which types of organizations to develop, the incubator was encouraged by the district MOCA bureau to incubate community-level social organizations.Footnote 28

5.3 Mass Organizations and Government Purchase of Services

Other than non-profit incubators, mass organizations—state-run organizations established to mobilize the public and propagate government policy—have increasingly become involved in the outsourcing process. The term ‘mass organizations’ in China refers to four organizations established to represent different sections of society: the Chinese Youth League (CYL), the All-China Women’s Federation, the All-China Trade Union, and the China Disabled Person’s Federation. The first party document to support this policy line was posted on state media Xinhua in 2015.Footnote 29 It stressed strengthening services provided by the mass organizations through government outsourcing towards social organizations, and broadly ‘guiding’ social organizations in the right direction.

Several experiments were conducted as early as 2010. For instance, in 2010, the Youth League Committee of the Qingdao CYL started public welfare project selection activities by receiving proposals from social organizations to implement programs related to preventing juvenile delinquency and crime.Footnote 30 Another case is that of the Hubei Provincial Women’s Federation, which has not only established a social organization incubation center with the cooperation of the Wuchang district government in Wuhan in 2014, but also has initiated the outsourcing of more than 96 welfare and cultural services related to migrant children, children’s safety, women’s employment, and women’s rights.Footnote 31

6 Linking Non-state Services and Political Support

This research draws from pre-existing literature in different country contexts, ranging from works on non-state services in the Middle East (Brooke 2017), party-affiliated services by the Vanvasi Kalyan Ashram (VKA) in India (Thachil 2011), and works on public administration in advanced democracies that examine how citizens’ experiences with non-state services affects political attitudes (Gustavsen et al. 2014). Although the non-state entities in these works differ in the degree to which the state can monitor and control the quality of their services, these studies offer several directions for theorizing about how these services in the context of China can impact political support.

These previous research studies, albeit different in their mechanisms or political settings, underscore that services, in these cases pertaining to core welfare services such as health and education, can bolster political support. I hypothesize that a similar outcome can be predicted in the case of services provided by welfare service organizations in China. Albeit a large quantity of service programs are not party-affiliated,Footnote 32nor do they fall under the category of core welfare services, such as health and education, the exposure to social services delivered by these organizations can lead to strengthened public support for the party-state through service quality and internal efficacy.

There are two components that can lead to increases in political support. One is quality of services. In the case of Islamic services offered by the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, recent research states that the perception of quality of services is the core element that leads to a better evaluation of candidates in the Islamist parties (Brooke 2017). In the case of VKA’s medical and educational services, it was also found that respondents with a favorable opinion towards the services offered by the VKA were more likely to show electoral support.

This subjective evaluation of the quality of services is tied to performance legitimacy. In the Chinese context, it had been argued by scholars that the CCP relies on a performance index to increase legitimacy, and that this strategy particularly pertains to policies adopted during the Hu-Wen era (Birney 2017). This strategy is reflected in party rhetoric about bolstering legitimacy by achieving GDP growth as well as welfare targets. Along these lines, the promotion of service organizations would not only signal party efforts to increase better governance but would also allow the party to increase political support through performance legitimacy.

The second element that links non-state services and political support is procedural legitimacy, which refers to belief in due process and fairness. It has been argued that while a new public management paradigm is aimed at increasing cost efficiency, it may erode procedural legitimacy by distancing bureaucracy from the citizen’s preferences (Pierre 2009). Consequently, the contractual relationship may expand the types of service provided and economic efficiency, yet values related to procedural legitimacy, such as expectations of representative process and due process, may be undermined (Brewer 2007).

In the context of China, whether procedural legitimacy is important in determining regime support can be subject to debate. The authoritarian political context does not guarantee a fair, participatory due process and, thus, it is plausible to expect that citizens have low expectations of fairness and the efficacy of the participatory channels. Therefore, their experience in participating in these channels does not lead to regime support. Yet, recent scholarship has found that experience in participatory channels such as elections, public commenting, and deliberative processes increases political support for the CCP (Birney 2017; Truex 2017).

In the context of non-state service provision where formal input channels are non-existent, whether procedural legitimacy exists could be captured by the belief that a person can influence the service outcome through existing non-institutional channels. In such a context, internal efficacy—the subjective belief that one can influence the content of services—can be a possible operationalization of procedural legitimacy.

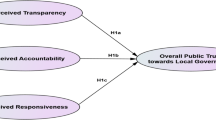

Taken together, the following hypotheses can be drawn from the above:

H1. Experience of receiving services leads to higher support for the government.

H2. Higher service quality leads to higher support for the government (performance legitimacy).

H3. Higher internal efficacy in influencing the content of service programs leads to higher support for the government (procedural legitimacy) (Fig. 1).

7 Research Design

7.1 Research Site

Shanghai was chosen as a research site for several reasons. First, Shanghai was one of the first batch of cities to experiment with the outsourcing of public, social, and administrative services, with the first outsourcing occurring in 1995. Shanghai is also the city that first implemented the incubation of non-governmental organizations. The first non-profit incubator (NPI) was founded in 2006 by a former MOCA official in the Pudong New District (PND). Upon its establishment, the PND MOCA bureau entered a 5-year non-competitive contract with an incubation organization called the NPI from 2007 to 2012.Footnote 33 Its responsibilities included providing services in developing non-profit organizations in the PND area. The NPI’s boundaries later expanded outside this area and it contracted with the Shanghai municipality as well as other districts.Footnote 34 The NPI model, which was later adopted by MOCA at the national level, has led to the establishment of similar incubators starting in 2012, leading to the construction of 26 incubators in Shanghai city alone by January 2018. The NPI’s model has been adopted in other cities, including Beijing, Shenzhen, Chengdu and Nanjing, Jiangxi, and Jinan.Footnote 35

Since Shanghai experienced the early development of engagement of social organizations in service delivery, it was an ideal location to test how citizens perceived the services offered by these organizations. Regarding the type of services, this research centered on social welfare services, except for two categories—elderly care, and care and services targeted at children and adolescents. For elderly care, the services were omitted from the research as I anticipated the respondents may have difficulty filling out the mobile survey. Research regarding children’s and adolescents’ services were not part of the study due to the complexity of obtaining parental consent. All other services pertaining to welfare and a broad categorization of social services were included in the research.Footnote 36

This research was conducted with master and undergraduate students at Fudan University located in Shanghai. The team was responsible for recruiting potential survey respondents and distributing the mobile survey.

7.2 Sampling Procedure

This research was carried out through fieldwork and a survey that was implemented across social welfare service organizations in five districts in the Shanghai metropolitan area. For the beneficiaries, I used a multistage clustered sampling method to sample the beneficiaries who received services from social service organizations, but within clusters. The beneficiaries were sampled using quota sampling. For the non-beneficiaries, I used quota sampling to sample a set number of non-beneficiaries from the matching neighborhoods. I explain the sampling procedure in detail below.

Although the preliminary plan was to randomly sample from service programs that are carried out in the districts and the neighborhood, such comprehensive data were not available. Thus, organizational-level information, such as the description of activities of these organizations, was used as a proxy to understand the content of services. Yet, because the location of the organizations did not necessarily equate to the organizations’ work sites, an extra step was taken to check where the organizations operated their projects.

Beneficiaries of services provided by these organizations and matching non-beneficiaries were sampled from mid-to-low income districts to reflect the diverse income levels of the respondents. To accommodate for the diversity of projects, I conducted a word frequency count of the descriptions of projects and categorized the organizations by service type.Footnote 37 Then, organizations registered at five mid-to-low income districts were randomly chosen for contact. To avoid focusing on one particular type of service, I created a list that contained an equal number of organizations across each service type. After contacting the service organizations, the beneficiaries of these services were recruited at the service sites.

Sampling non-beneficiaries was not easy due to a lack of knowledge regarding the population. Also, since a household roster was not publicly available, I could not randomly sample from an exhaustive list. Therefore, instead, I used quota sampling to sample non-beneficiaries for a given geographical area. Once I verified the neighborhood where each organization was providing services, I randomly chose six residential areas (xiaoqu) from the neighborhood, and then sampled two respondents from each area. If the respondent had previous experience with social service organizations, I excluded their responses and continued recruiting in the area until the quota was reached. Also, to reflect the fact that organizations cater to subsets of the population, non-beneficiaries were oversampled compared to beneficiaries. The sample of non-beneficiaries for a given activity area was approximately double compared to beneficiaries.Footnote 38 To minimize potential bias, the survey recruiters were sent to residential communities during late mornings on weekends, so residents were most likely to be at home.

Some caution was also used when choosing sites to recruit survey respondents. During the research process, it was found that there was an uneven development of the purchase of services from welfare organizations across Shanghai areas. For instance, compared to central districts, districts on the outskirts of Shanghai even lacked supporting institutions such as social organization service centers. Furthermore, some such centers were barely starting their operations, and there was little information or knowledge about organizations within the district.Footnote 39 Informants mentioned that a few reasons for the imbalance were that some neighborhoods lacked the capacity to engage in government purchasing or lacked the finances to do so.Footnote 40 The level of active purchase of services from these organizations was also dependent on the preferences of the grassroots government leadership.Footnote 41Footnote 42 For these reasons, organizations registered at two of the lowest-income districts were omitted from the sampling process (Fig. 2).

The format of the survey was electronic, whereby the respondents were asked to fill out the survey by scanning a QR code that led to the electronic survey on their own mobile phones. Using a mobile electronic survey had several advantages compared to a traditional survey. First, the electronic platform made data collection and processing manageable. Second, the electronic platform was cost effective and less time consuming because survey recruiters did not need to enumerate the survey instruments to each respondent. Lastly, an electronic survey is known to lead to less social desirability bias compared to traditional surveys because respondents can complete surveys on their own. To minimize satisficing, the survey questions were randomly shuffled.Footnote 43 One concern in the use of the electronic survey method is accessibility. Respondents without a smartphone may have no choice but to reject participation, due to lack of access to a smartphone. This problem did manifest during the sampling procedure, but the rejection rate among respondents due to inaccessibility was small.Footnote 44

It should be noted that the sampling procedure used here poses limits to the external validity of the study. Due to constraints in time and resources, this study has used organization-level information for sampling rather than project-level information, which is not publicized. A further examination of project-level information, such as the location and the service type, could be used to create a more accurate estimation of the population of service recipients and improve the representativeness of the sample. Second, the sample size is small, which later, when statistical analyses are applied, creates limits in external validity. I add more possible directions for improvement in the conclusion.

7.3 Organizations from Which Beneficiaries Were Sampled

Beneficiaries in the analysis were drawn from seven organizations across five districts. As the organizations were engaged in multiple services, before recruiting them, we called each organization and checked their on-going service projects. If an organization was operating multiple services, I chose the project that services the marginalized, as opposed to encompassing projects. The projects from which beneficiaries were sampled and the boundary of targeted beneficiaries is summarized in Table 1.

Other characteristics of the sampled organizations, such as who established an organization or whether it was participating in government purchases is summarized in Online Appendix Fig. 9. Out of seven sampled organizations, five were established by the government, and six were in contract with the government.

7.4 Operationalization and Measurement of Variables

The dependent variable of this study was regime support or political support, which I operationalized as political trust.Although political support and political trust are conceptually different, it has been argued by scholars that political trust is an expression of diffuse support—support for the regime and state—which is distinct from specific support, such as support for an incumbent or evaluation of an output (Easton 1975). Also, political trust has been argued to be fundamental to the legitimacy of the state (Levi and Stoker 2000), which has led to frequent use of the indicator to measure political legitimacy (Gilley 2006; Whiting 2017; Dickson et al. 2016).

The dependent and independent variables were measured using five-item Likert-scale responses. In the analyses, these variables were considered as ordinal categorical variables. For the dependent variable on political trust, respondents were asked how much they trust in respective government institutions. The question stated was, “How much do you trust in the government institutions below?” Five Likert-scale responses were given as options for four respective government institutions: residents’ committee, neighborhood committee, local government, and the central government.

There were three independent variables for the three respective hypotheses: exposure to services, service quality, and internal efficacy towards services (service efficacy). Exposure to services was captured by a dummy variable denoting whether or not the respondent was sampled from the beneficiaries’ group. Service quality was measured by asking respondents about service satisfaction. The question asked was, “Are you satisfied with the service(s) you receive here?” Internal efficacy towards services was measured by asking respondents how much they believed they could affect the contents of services if they wished to. The question stated was, “How much change do you think you can make regarding the services you receive?”.

For control variables, I included age, income before tax, and a dummy variable that indicated whether the respondent held Shanghai household registration (hukou).Footnote 45 Although the survey asked age and income in categories,Footnote 46 I coded the categories as continuous to improve the interpretability of the model. Ages were categorized from one to seven, ranging from “below 20 years old” (1) to “above 70” (7). Income was categorized from one to six, ranging from below 50,000 Yuan (1) to above 500,000 Yuan (6).

Table 2 shows summary statistics for the beneficiaries and the non-beneficiaries’ groups. Compared to the non-beneficiaries’ sample, the beneficiaries’ sample is older, as the mean age falls into the above 40 and below 50 category, whereas for non-beneficiaries, the mean age is above 20 and below 30. Beneficiaries were more likely to be female than male, hold household registration, and have lower income.

8 Analysis and Results

8.1 Baseline Ordinal Logistic Regression and Coarsened Exact Matching

Is there a correlation between receiving services from social service organizations and political trust? I tested the first hypothesis using ordinal logistic regression (OLR). The responses regarding trust in the respective levels of the government were coded ordinally, where the orders were 1 = Strongly Do Not Trust; 2 = Do Not Trust; 3 = Neutral; 4 = Trust; and 5 = Strongly Trust. Standard errors were clustered at the neighborhood level (Table 3).

The OLR results do not show support for the first hypothesis. The odds ratios for the four dependent variables were all below one, which indicates that the odds of beneficiary respondents answering that they had higher levels of trust in government institutions were lower than non-beneficiary respondents. In all, there was no support that services changed the level of political support.

8.2 Coarsened Exact Matching Analysis

Although OLR can deliver unbiased estimates of the independent variable, the exact relationship between the independent variable and the outcome variable is difficult to understand especially when the covariates that are correlated with the dependent variable are distributed differently between the two groups.Footnote 47 In the potential outcomes framework, it is unclear in the data set whether respondents in the beneficiaries group are randomly assigned. If these respondents harbor some unobserved or observed characteristics that are positively correlated with the outcome variable of political trust, then it becomes difficult to substantiate whether having received services actually affects political trust. Thus, to remove the sole effect of having received services and obtain the feasible sample average treatment effect, two groups were needed: a beneficiary group and a non-beneficiary group that is a counterfactual of the beneficiary group. The former is equivalent to a treatment group, which has received services, and the latter as a control group. Two groups are then needed, balanced on confounding variables except for the treatment variable.

I conducted the matching process using the coarsened exact matching (CEM)Footnote 48,Footnote 49algorithm and substantiated it with the OLR, with two caveats. First, the sample size for the analysis was limited. Matching is a data preprocessing step where observations within the data set are pruned so that covariates are distributed equally between the treatment and control groups, thus achieving a reduction in imbalance. However, problems may rise when the sample is small—matching reduces the number of observations in the data set and increases variance. In the case of the data set used here, matching the treatment and the control group based on four collected covariates decreased the sample size significantly.Footnote 50

Due to the caveat above, I did not proceed with exact matching, which is equivalent to pruning observations based on all available covariates but decreased the imbalance between the beneficiaries and the non-beneficiaries’ groups by matching on a few selected covariates. I then controlled the remaining imbalance using OLR. I chose three covariates to match the two groups—age, household registration status, and gender. These were selected based on statistical significance and coefficient size.Footnote 51 This analysis does not meet the conditions of a randomized experiment where all the confounders are matched for both beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries’ groups but approximates the design by controlling for a few confounders and then examining the effect of service on the approximate balanced data set.

Table 4 shows the change in the multivariate L1 distance before and after matching. This captures the difference between the multidimensional histogram of pretreatment covariates in the treated group and the same in the control group (Iacus et al. 2012). Perfect global imbalance is indicated by zero, larger values indicate a larger imbalance, and one denotes a complete separation. The multivariate L1 distance in Table 4 shows that the imbalance decreased significantly after using the matching algorithm (Table 5).

The results show that, when matching the beneficiaries and the non-beneficiaries’ groups on three covariates—age, gender, and household registration status, being a beneficiary of services provided by social service organizations increases trust levels for the neighborhood government, local government, and the central government, but not for the residents’ committee. The size of the coefficients and statistical significance indicates that there is some support for the first hypothesis, but only for the dependent variable of trust in central government. The odds of a beneficiary respondent answering that they had higher levels of trust towards the central government was 140% higher compared to a non-beneficiary respondent, and the coefficient estimate was statistically significant at a 10% confidence level.

Figure 3 compares the OLR and CEM OLR coefficient estimates. Compared to OLR without matching, the CEM OLR results increase the coefficient estimates for three dependent variables: trust in the neighborhood committee, trust in the local government, and trust in the central government, but not for trust in the residents’ committee.

8.3 Testing Effects of Service Satisfaction and Service Efficacy on Political Trust

To test hypotheses two and three, I conducted two separate OLRs on the four outcome variables using service satisfaction and service efficacy as independent variables. Since the sample collected for beneficiary respondents was small at N = 35, I only controlled for age.Footnote 52

The odds ratios reported in Table 6 show that although service satisfaction was larger than one for the service satisfaction variable they were not statistically significant, which then implies that the second hypothesis—that higher service quality leads to higher political trust—can be rejected. On the other hand, the third hypothesis, which was that higher service efficacy (the internal belief that one can affect the content of the services) leads to higher support for the government, cannot be rejected due to the high odds ratio and statistical significance. The odd ratios were above one and statistically significant at a 1% level for trust in all levels of the government. Overall, the results suggest that although two factors—the increase in service satisfaction and service efficacy—increase trust in government institutions, service efficacy stands out as the key factor that links the experience of receiving services and political trust.

Figure 4 plots the log-odds regression coefficient estimates of the OLR output in Table 6. The plots show that the two variables—service efficacy and service satisfaction—have positive effects on the dependent variable of political trust for all levels of the government: the residents’ committee, the neighborhood committee, the local government, and the central government. However, compared to the coefficient estimate of the service satisfaction variable, that of service efficacy is larger, which implies that there is a stronger correlation between the service efficacy variable and political trust than service satisfaction and political trust.

8.4 Who is Perceived as Accountable for the Services?

If internal efficacy toward services is relevant to increasing political support, then in what ways do people attempt to influence the content of services? One way to glean an answer is by examining who residents perceive to be accountable for services. The question on accountability asked, “If you want to demand responsibility for the services you received, to whom will you demand responsibility?” The answer options included neighborhood committee, residents’ committee, social service organization, and other.

Figure 5 shows the distribution of answers to the accountability question. The majority, 45.7% of the respondents, answered that the social organization was responsible for the services. A slightly higher proportion, 51.4% of the respondents, attributed responsibility to grassroots institutions—the neighborhood and the residents’ committee. The findings that the responsibility regarding services was attributed to grassroots institutions and social service organizations, yet receiving services increased political trust in the central government, attests to credit transfer.

9 Discussion

Recent studies of NGOs in China have covered a wide range of aspects such as political participation of NGOs in law-making (Froissart 2019); causes of state–NGO collaboration (Farid and Song 2020); and causes of variation in grassroots activism (Gao 2020). This article touched upon an aspect of NGOs in China that warrants attention—outsourcing of social services. The recent launch of government purchase of services in the areas of public administration and social welfare in China has led scholars to assess the consequences of these new programs, such as inequality (Cho 2017) and the degrees of devolution (Gao and Tyson 2017). This research, by drawing more from the literature on consequences of non-state services and service reforms in advanced democracies, examined how the new configuration of service provision brought about by the government purchase system can affect political attitudes, specifically, political trust in government institutions.

The research results above show that being a beneficiary of services provided by social service organizations increases trust in government institutions, and the effect is statistically significant for the central government level. Two mechanisms were tested—quality of services and internal efficacy. Although quality of services and internal efficacy both showed positive correlations with indicators on trust in government institutions, service efficacy stood out as the key factor that links the experience of receiving services and trust in the central government.

An important finding of this research is that although recipients attributed accountability to social service organizations and the grassroots administrations, it is only the central government that enjoys increased political support, which attests to credit transfer. This result differs from other works on non-state services regarding core services. When non-state services fill a role of the state that is perceived to be primary, such as health care, such services may decrease trust in the state (Cammet et al. 2015). In areas such as urban China, where non-state services do not compete with core services and compensate for the role of the state, works by non-state agents rather boosts support for the state.

The findings of this paper also provide support for the growing literature that finds that procedural legitimacy is important in bolstering political support in China. Prior work on political support in China focused on performance legitimacy, for instance, linking public goods spending and political support (Dickson et al. 2016), while recent works have found support for procedural legitimacy by examining citizens’ exposure to participatory channels (Truex 2017; Birney 2017). This paper also offers support for the view that procedural legitimacy is relevant to explaining political support in China.

The findings here also align with the findings on hierarchical trust in China. Studies on political trust in China have consistently found that citizens portray higher trust in the central government, in contrast to their trust in the local government (Li 2013; Saich 2012). This is in part strengthened by the regime-controlled media that blame local government institutions for misconduct, but also by decentralization, which makes local governments responsible for social policy outcomes (Lü 2014). The findings of this paper portray a similar mechanism of unintended credit transfer towards the central government, which is accompanied by offloading responsibility to lower-level institutions.

While this research has produced some significant new findings, the sampling method used for the data collection poses limits to external validity. As mentioned in the methodology section, the clusters could be constructed differently to increase the representativeness of the sample of service recipients. To achieve this, a necessary step would be to verify whether organizations carry out projects in their respective registered district and ascertain the location of the project sites. Then, clusters could be created so that they reflect the distribution of projects by service type. A larger sample would also be useful for improving the external validity of this study.

Moreover, further questions remain to be explored; for instance, how does perception of service accountability interact with service satisfaction? The first hypothesis does not make assumptions about how citizens perceive service accountability. The theory assumes that when the public receive services, performance legitimacy rises due to people’s perception that services are provided by the state. However, this link does not reflect whether this is due to the perception that the state is accountable for the services. Future efforts will shed more light on this question.

Notes

In this paper, I use the term ‘social service organizations’ throughout to refer to both grassroots NGOs and GONGOs engaged in social service delivery.

In the developing world, non-state entities that provide social and public services are comprised of a broader set of actors, including non-profits, commercial businesses, drug cartels, terrorist groups, ethnic or sectarian organizations, and faith-based organizations (Cammet and MacLean 2014).

Most influential is the “new public management” paradigm, which originates from neo-liberal shifts in administrative sciences in Anglo-Saxon countries in the late 1970s.

The slogan first appeared at the 15th Party Congress in September 1997.

This process takes the form of purchasing bureaus partnering with private or state corporations. These entities provide funds and social organizations apply by bidding to obtain funds.

Venture philanthropy differs from government procurement in that funding for government purchases could include different entities, such as a commercial entity or an individual. Venture philanthropy and government procurement platforms exist at different levels. There is a national government procurement website, district and neighborhood level website announcements, mass organization websites, and venture philanthropy bidding sites.

According to a survey conducted by Zhao (2010) on sampled public service units in Qingdao in 2009, 53% of all respondents working in public service units answered that maintaining the status quo is the right direction for public service unit reform, while 20% agreed with the option of transforming towards enterprise or a non-profit unit. When asked what they considered the biggest challenge for public service units when transforming to a non-profit unit, a majority answered, “turning government employees to non-government employees”, and “changing the status of the unit’s asset from government to non-governmental”.

According to the Temporary Provision on Management of Government Procurement of Services (zhengfugoumaiguanlibanfa) released in 2014, purchasing bodies are limited to “administrative bureaus at all levels and public service units with administrative functions”. Providers include registered social organizations, second category public welfare public service units, or public service units that have transformed into enterprises, registered enterprises, and other social forces.

The first policy directives on community construction can be traced back to the late 1980s. The emphasis on the role of social organizations in delivering community services was made in the 2011 12th Five-Year Plan.

Approximately 34% out of all social welfare NGOs in Shanghai were involved in activities at the community level. Online Appendix Fig. 6.

Interview with a grassroots NGO, December 2016.

Interview with a grassroots NGO, December 2015.

This supervisory organization should be a government entity, which makes it difficult for grassroots organizations to obtain registration.

One grassroots organization told me that they were able to become registered quickly because their head had connections with the Youth League (Interview with a grassroots NGO, December 2015).

Interview with a grassroots NGO, December 2015.

Announced by the Organization Department of the Central Committee, 28 September 2015.

Out of all designated funds, 194 million RMB was approved with auxiliary funds of 785 million RMB. Auxiliary funds include local government funding as well as social funds (Han 2015).

Research on government purchase of services from social organizations, conducted by the China Charity Information Center, funded by the Asia Foundation, published in February 2015.

It was found that out of 942 projects outsourced to social organizations in Shanghai from 2009 to 2013, 55.2% of them were limited to the neighborhood (Guan and Xia 2016).

There is variation across regions in terms of usage of the project system to distribute funds. In Shanghai, the standardized method is the project system (xiangmuzhi), while in Guangzhou, the unit system (danweizhi) is used. Rather than giving neighborhood governments the authority to purchase services from social organizations, in Guangzhou, this authority is given to the “Domestic Comprehensive Service Centers (DCSC, jiatingzonghefuwuzhongxin)” in each neighborhood. Funds are distributed from the neighborhood government then to the DCSC, and the DCSC is responsible for the purchase and evaluation of services (Guan and Xia 2016).

An itemized list is released with detailed codes pertaining to projects. Largely, projects are divided into four categories: A. development projects located in western China; B. social service projects such as social assistance, poverty relief, social welfare, and community services; C. social work activities; D. personnel training projects (Han 2015).

Opinions on Implementing Government Purchase of Services from Social Organizations, Shanghai, Jingan District, released 5 July 2011.

Interview with an NGO incubator, September 2017.

Interview with an NGO incubator, August 2017.

Han (2015).

Interview with an NGO incubator, December 2017.

Han (2015).

“Opinions Regarding Strengthening and Advancement of Work by Mass Organization”. Xinhua News Site. 9 July 2015. http://www.xinhuanet.com//politics/2015-07/09/c_1115875561_3.htm. (accessed March 2018).

“About How the Chinese Youth League Should Deal with Government Purchase of Services.” Chinese Youth League News Site, 20 October 2014. http://sd.youth.cn/2014/1020/467255.shtml (accessed March 2018).

Annual report on “Mulan Public Welfare (gongyimulan)”, a brochure of public welfare programs created by the Hubei Province Women’s Federation, obtained 11 December 2017.

Online Appendix Fig. 8. To identify party-affiliated organizations, I used ‘having a supervisory organization as a party unit’ as a proxy. According to data on registered NGOs in Shanghai I gathered in March 2017, I found that approximately 11.5% of NGOs in Shanghai are party-affiliated.

Interview with an NGO incubator, December 2016.

Examples include research project on “How to standardize process of government purchase of services from nonprofits” contracted by Pudong New District Bureau of Finances in 2007.

Enpai shengji 2.0 banben (Enpai Upgrades to Version 2). http://www.chinadevelopmentbrief.org.cn/news-16083.html (accessed March 2018).

Online Appendix Fig. 7.

Online Appendix Fig. 7.

The fixed quota was N = 5 for beneficiaries, N = 12 for non-beneficiaries for each organization and the respective neighborhood in which the organization was running the program.

Interview with a social organization service center, December 2016.

Interview with a neighborhood committee, December 2018.

Interview with a social organization service center, December 2018.

For instance, in one neighborhood in Wuhan, the party secretary preferred to mobilize volunteers rather than purchase services from social organizations, because she preferred a self-grown service rather than relying on organizations outside the neighborhood.

Survey questions were shuffled group-wise as well as within-group. For instance, one group would consist of questions on political trust, another would consist of service experience.

There were two cases where respondents rejected the survey due to having no smartphone.

A low-income assistance variable was omitted from the model, due to lack of variation. Ten out of 119 respondents answered that they were currently receiving low-income assistance.

The questions did not ask respondents to insert their age, but to choose from categories; for example, “under 20” or “20 or above but below 30”.

This could also be generated due to quota sampling.

‘Coarsening’ refers to the process of matching treatment and control groups on covariates. Compared to other matching techniques, CEM does not match the two groups based on identical covariate values but matches after coarsening each variable into groups (Blackwell et al. 2009).

CEM analysis was performed using the CEM package in STATA version 15.1.

When four covariates—age, gender, household registration status, and income levels—were used for CEM, the sample was reduced to N = 28.

The OLR results with only covariates are reported in Online Appendix Table 7.

Previous work on political trust in China finds age to be a strong predictor of political trust levels (Dickson et al. 2016). The results of the OLR on political trust using controls show that age is a strong predictor compared to all other covariates (Online Appendix Table 7).

References

Birney, Mayling. 2017. Beyond Performance Legitimacy: Procedural Legitimacy and Discontent in China. Working Paper Series (17–189).

Blackwell, Matthew, Stefano Iacus, Gary King, and Giuseppe Porro. 2009. Cem: Coarsened exact matching in stata. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata 9 (4): 524–546.

Brewer, Brian. 2007. Citizen or customer? Complaints handling in the public sector. International Review of Administrative Sciences 73 (4): 549–556.

Brooke, Steven. 2017. From medicine to mobilization: Social service provision and the Islamist reputational advantage. Perspectives on Politics 15 (1): 42–61.

Cammett, Melani, Julia Lynch, and Gavril Bilev. 2015. The influence of private health care financing on citizen trust in government. Perspectives on Politics 13 (4): 938–957.

Cammett, Melani, and Lauren M. MacLean, eds. 2014. The Politics of Non-state Social Welfare. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Chan, Cecilia L. W. 1993. The Myth of Neighbourhood Mutual Help: The Contemporary Chinese Community-Based Welfare System in Guangzhou. Hong Kong University Press.

Cho, Mun Young. 2017. Unveiling Neoliberal Dynamics: Government Purchase (Goumai) of Social Work Services in Shenzhen’s Urban Periphery. The China Quarterly 230: 269–288.

Diamond, Larry J. 1994. Toward democratic consolidation. Journal of Democracy 5 (3): 4–17.

Dickson, Bruce J., Pierre F. Landry, Mingming Shen, and Jie Yan. 2016. Public goods and regime support in urban China. The China Quarterly 228: 859–880.

Easton, David. 1975. A re-assessment of the concept of political support. British Journal of Political Science 5 (4): 435–457.

Elinder, Mikael, and Henrik Jordahl. 2013. Political preferences and public sector outsourcing. European Journal of Political Economy 30: 43–57.

Farid, May, and Chengcheng Song. 2020. Public trust as a driver of state-grassroots NGO collaboration in China. Journal of Chinese Political Science 25: 591–613.

Froissart, Chloé. 2019. From outsiders to insiders: The rise of China ENGOs as new experts in the law-making process and the building of a technocratic representation. Journal of Chinese Governance 4 (3): 207–232.

Gao, Huan. 2020. The power of the square: Public spaces and popular mobilization after the Wenchuan Earthquake. Journal of Chinese Political Science 25: 89–111.

Gao, Hong, and Adam Tyson. 2017. Administrative reform and the transfer of authority to social organizations in China. The China Quarterly 232: 1050–1069.

Gilley, Bruce. 2006. The meaning and measure of state legitimacy: Results for 72 countries. European Journal of Political Research 45 (3): 499–525.

Guan, Bing, and Wei Xia. 2016. Zhengfu Goumai Fuwude Xuanze Ji Zhili Xiaoguo: Xiangmuzhi, Danweizhi, Hunhezhi (Institutions of Government Purchase of Services and Effectiveness: Project System, Danwei System, Combined System). Guanli Shijie 8.

Gustavsen, Annelin, Asbjørn Røiseland, and Jon Pierre. 2014. Procedure or performance? Assessing Citizen’s attitudes toward legitimacy in Swedish and Norwegian local government. Urban Research & Practice 7 (2): 200–212.

Han, Jun. 2011. NGO Zenme Chengwei Shehui Zhuanxing Niudai —NPI de Shijian (How Does NGO Become a Nexus of Social Transformation? NPI Practices). Luye.

Han, Jun. 2016. The emergence of social corporatism in China: Nonprofit organizations, private foundations, and the state. China Review 16 (2): 27–53.

Han, Junkui. 2015. Government-NPO relations in service procurement: Quasi-corporatist and quasi-pluralist practices and challenges in China. The China Nonprofit Review 7 (1): 90–109.

Heberer, Thomas, and Christian Göbel. 2011. The politics of community building in urban China. Routledge.

Henderson, Gail E., and Myron S. Cohen. 1984. The Chinese hospital: A socialist work unit. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Howell, Jude. 2016. Adaptation under scrutiny: Peering through the lens of community governance in China. Journal of Social Policy 45 (3): 487–506.

Iacus, Stefano M., Gary King, and Giuseppe Porro. 2012. Causal inference without balance checking: Coarsened exact matching. Political Analysis 20 (1): 1–24.

Lamothe, Meeyoung, and Scott Lamothe. 2010. Competing for what?: Linking competition to performance in social service contracting. The American Review of Public Administration 40 (3): 326–350.

Leung, Joe C. B., and Richard C. Nann. 1995. Neighborhood-based welfare in the urban areas. In Authority and benevolence: Social welfare in China, 133–204. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press.

Levi, Margaret, and Laura Stoker. 2000. Political trust and trustworthiness. Annual Review of Political Science 3 (1): 475–507.

Li, Lianjiang. 2013. The magnitude and resilience of trust in the center. Modern China: 34.

Li, Mei. 2015. The Reform of Public Service Units in China: A Decentralization Approach. In Governance in South, Southeast, and East Asia, eds. Ishtiaq Jamil, Salahuddin M. Aminuzzaman, and Sk. Tawfique M. Haque, 191–210. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Lü, Xiaobo. 2014. Social policy and regime legitimacy: The effects of education reform in China. American Political Science Review 108 (2): 423–437.

MacLean, Lauren M., and Melani Claire Cammett. 2014. The politics of non-state welfare. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Osborne, David, and Ted Gaebler. 1992. Reinventing government: How the entrepreneurial spirit is transforming the public sector. Reading: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.

Picazo-Tadeo, Andrés J., Francisco González-Gómez, Jorge Guardiola Wanden-Berghe, and Alberto Ruiz-Villaverde. 2012. Do ideological and political motives really matter in the public choice of local services management? Evidence from urban water services in Spain. Public Choice 151 (1–2): 215–228.

Pieke, Frank N. 2012. The Communist Party and Social Management in China. China Information: 17.

Pierre, Jon. 2009. Reinventing governance, reinventing democracy? Policy & Politics 37 (4): 591–609.

Pierre, Jon, and Asbjørn Røiseland. 2016. Exit and voice in local government reconsidered: ‘A choice revolution’? Exit and voice in local government. Public Administration 94 (3): 738–753.

Saich, Anthony. 2012. The Quality of Governance in China: The Citizen’s View. HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series RWP12-051.

Savas, Emanuel. 1987. Privatization: The key to better government. Chatham: Chatham House Publishers.

Spires, Anthony J. 2011. Contingent symbiosis and civil society in an authoritarian state: Understanding the survival of China’s Grassroots NGOs. American Journal of Sociology 117 (1): 1–45.

Sundell, Anders, and Victor Lapuente. 2012. Adam Smith or Machiavelli? Political incentives for contracting out local public services. Public Choice 153 (3–4): 469–485.

Teets, Jessica C. 2014. Civil Society under Authoritarianism: The China Model. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Thachil, Tariq. 2011. Embedded mobilization: Nonstate service provision as electoral strategy in India. World Politics 63 (03): 434–469.

Thornton, Patricia M. 2016. NGO Governance and Management in China. In NGO governance and management in China, eds. R. Hasmath and Jennifer Hsu. London: Routledge.

Truex, Rory. 2017. Consultative authoritarianism and its limits. Comparative Political Studies 50 (3): 329–361.

Tyler, Tom R. 2001. A psychological perspective on the legitimacy of institutions and authorities. In The psychology of legitimacy: Emerging perspectives on ideology, justice, and intergroup relations, 416–36. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Whiting, Susan H. 2017. Authoritarian ‘Rule of Law’ and Regime Legitimacy. Comparative Political Studies 50 (14): 1907–1940.

Zhao, Libo. 2010. Shiyedanwei Shehuihua Yu Minjianzuzhi Fazhanyanjiu (Socialization of Public Service Units and Development of Non-Governmental Organizations). Shandong Renmin Chubanshe.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Funding was provided by Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society, Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies at Stanford University, and Fudan University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, E.E. How Outsourcing Social Services to NGOs Bolsters Political Trust in China: Evidence from Shanghai. Chin. Polit. Sci. Rev. 9, 36–62 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-021-00207-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-021-00207-z