Abstract

Political selection institutions in non-democracies are usually conceptualized as mechanisms to co-opt competent agents for regime survival. Departing from this common emphasis, this article highlights their linkage function between informal politics and policy outcomes. Using multilevel modeling and error correction models, hypotheses on the determinants and implications of formal political selection rules are tested. Drawn from an original dataset of political selection rules in China, this analysis finds that coalitions with particular policy priorities strive to achieve desired policy outcomes through shaping formal political selection institutions. The geographic variation in specific features of the political selection rules is primarily driven by coalitional politics. In addition, the effect of policy performance on local leaders’ promotion prospects is not uniform but conditioned on the political selection rules. Under such incentive arrangements, local leaders are found to expand government spending in the policy area prioritized in formal political selection rules. These findings advance our understanding of the endogenous political nature of political selection rules and the relations between informal institutions and policy performance.

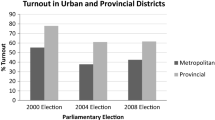

Source: Author’s dataset

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, Landry et al. (2018) show that whereas loyalty is paramount for those within the selectorate, local politicians distant from the core of power are promoted on the basis of competence in economic development. Jia et al. (2015) find a complementary role of personal connections and work performance, and top leaders pick the most talented subordinates in the pool of loyal officials. See Wang (2021) for a review on the post-Mao cadre management regime in China.

Some recent research highlighted that the performance itself is partly endogenous to political connections (see Jiang 2018).

For example, factions are found to affect promotion outcomes (e.g.: Shih et al. 2012; Jia et al. 2015), anticorruption (Zhu and Zhang 2017), bank lending (Shih 2004), inflationary cycles (Shih 2008a), policy process (Chung 2000), and ideological campaigns (Shih 2008b). Fiscal transfer also serves as a mediating factor between performance and factionalism (see Wong 2022).

Economic targets include those related to industry, investment, and fiscal revenue (see the category of “economic development” in Table 1 in Online Appendices). Those regarding education, public health, environment, and culture are social targets (see the categories of “social development”, “sustainable development”, “people’s welfare”, and “cultural construction” in the appendix table). Political targets contain those related to administrative and judicial system, and party affairs (see “political construction” and “party building” categories in the appendix table).

See Ning and Zuo (2022).

In the sample, points assigned to economic target points vary from 27 to 64 out of 100, whereas those of social welfare targets vary from 24 to 73.

In the sample, two provinces, Anhui (2011–2015) and Guangdong (2008), have adopted the classified evaluation (fenlei kaohe) approach and TRS point schemes vary across different categories of prefectures within each province to accommodate local needs. For the four types of cities in Guangdong, the economic target points and social target points are 0.30 and 0.70, 0.31 and 0.69, 0.33 and 0.67, and 0.27 and 0.73, respectively, where social target points far exceed economic ones for all types of cities. For the four types of cities in Anhui, for example in 2011, the economic target points and social target points are 0.60 and 0.40, 0.58 and 0.42, 0.58 and 0.42, and 0.49 and 0.51, respectively. Only the city in the fourth category (i.e., Huangshan) differs from the rest of cities in the TRS point scheme pattern due to the priority of Huangshan in developing tourism and therefore having more points assigned to the “sustainable development” category.

For more information on Xitong, please see Lieberthal (2003).

http://103.247.176.86/eventgis/index.html, accessed in January 2017.There is no consistent public record on social unrest in China.

Fisher type xtunitroot test indicates that the growth and the level of government revenue are non-stationary, thus they are not included in the model.

http://www.clb.org.hk, accessed in December 2017.

http://ngdc.noaa.gov/eog/dmsp/downloadV4composites.html, accessed in December 2017.

This generates a mayor sample of 184 observations (mayor-tenure) from 116 prefectures in 12 provinces, and a party secretary sample of 161 observations (party secretary-tenure) from 114 prefectures in 14 provinces. Nine cases where leaders were removed from office due to corruption are treated as “abnormal” causes of leadership turnover and excluded from analysis.

Using “leader-year” is problematic, because it assumes that work performance before year T has no effect on the career move that occurred in year T. However, interviews show that the provincial party organization department takes into account the overall performance during the city leader’s tenure and compares to that of the rest of cities in the same province, rather than the most recent year’s performance, when making personnel decisions (Interview JX19111505, BJ10311201).

Using immediate political outcome or political outcomes 2 years after the completion of tenure don’t change the substantive story in the analysis.

These three environmental measures are the comprehensive utilization ratio of industrial solid wastes, centralized treatment ratio of wastewater, and decontamination rate of domestic waste.

Another common class of models is the autoregressive distributed lag (ADL) model. Choosing to estimate the ADL or ECM is largely a matter of “ease of interpretation” (De Boef and Keele 2008, 190).

Spending on environmental protection is not included due to data inconsistency.

Unfortunately, systematic and consistent city-level data on the proportion of age groups below 18 or the elderly population is not available in statistical yearbooks.

A decrease in social spending may be caused by government incentive to attract investment and cut down labor cost, whereas urbanization can lead to the increase in social spending. Urbanization, economic openness, and marketization are measured by the ratios of urban residents to total population, FDI to GDP, and non-SOE employees to labor pool, respectively.

The statistically significant and negative coefficients of the lagged level of TRS point differences in models 2, 4 and 6 in Table 4 suggest that adhering to the pro-welfare TRS points might lead to declining social spending ratio in the long run. One possible explanation is that the lagged level of TRS point differences is associated with more fiscal resources allocated to the social welfare areas in the previous year (see correlational table, Table B.3 in Online appendix), therefore without further expanding the TRS point difference and signaling the continuation of increasing emphasis on social welfare, the ratio of social spending would regress. Yet, since the statistical significance of the coefficient is not robust in at least two models, therefore, the negative long-term effect is not supported with strong evidence.

References

Acemoglu, Daron, Georgy Egorov, and Konstantin Sonin. 2010. Political selection and persistence of bad governments. Quarterly Journal of Economic 125 (4): 1511–1575.

Beck, Nathaniel, and Jonathan Katz. 1995. What to do (And Not to Do) with time-series cross-section data. American Political Science Review 89: 634–647.

Bell, Daniel. 2015. The China model. Princeton University Press.

Besley, Timothy, Rohini Pande, and Rao, Vijayendra. 2005. Political Selection and the Quality of Government: Evidence from South India. working paper.

Birney, Mayling. 2014. Decentralization and veiled corruption under China’s ‘Rule of Mandates.’ World Development 53: 55–67.

Boucek, Francoise. 2009. Rethinking factionalism: Typologies, intra-party dynamics and three faces of factionalism. Party Politics 15 (4): 455–485.

Caselli, Francesco, and Massimo Morelli. 2003. Bad politicians. Journal of Public Economics 88: 759–782.

Chen, Jing, and Cui Huang. 2021. Policy Reinvention and Diffusion: Evidence from Chinese Provincial Governments. Journal of Chinese Political Science 26: 723–741.

Chung, Jae Ho. 2000. Central control and local discretion in China. Oxford University Press.

De Boef, Suzanna, and Luke Keele. 2008. Taking time seriously. American Journal of Political Science 52 (1): 184–200.

Dewan, Torun, and Francesco Squintani. 2016. In defense of factions. American Journal of Political Science 60 (4): 860–881.

Distelhorst, Greg, and Yue Hou. 2017. Constituency service under nondemocratic rule: Evidence from China. Journal of Politics 79 (3): 1024–1040.

Edin, Maria. 2003. State capacity and local agent control in China: CCP Cadre management from a township perspective. The China Quarterly 173 (1): 35–52.

Egorov, Georgy, and Konstantin Sonin. 2011. Dictators and their viziers: Endogenizing the loyalty competence trade-off. Journal of the European Economic Association 9 (5): 903–930.

Gandhi, Jennifer. 2008. Political institutions under dictatorship. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Gandhi, Jennifer, and Ellen Lust-Okar. 2009. Election under authoritarianism. Annual Review of Political Science 12: 403–422.

Gao, Jie. 2009. Governing by goals and numbers: A case study in the use of performance measurement to build state capacity in China. Public Administration and Development 29: 21–31.

Gao, Jie. 2015. Pernicious manipulation of performance measures in China’s cadre evaluation system. China Quarterly 223: 618–637.

Geddes, Barbara. 1999. What do we know about democratization after twenty years? Annual Review of Political Science 2 (1): 115–144.

Gelbach, Scott, Konstantin Sonin, and Ekaterina Zhuravskaya. 2010. Businessman candidates. American Journal of Political Science 54 (3): 718–736.

Grzymala-Busse, Anna. 2010. The best laid plans: The impact of informal rules on formal institutions in transitional regimes. Studies in Comparative International Development 45 (3): 311–333.

Heberer, Thomas, and René Trappel. 2013. Evaluation processes, local cadres’ behaviour and local development processes. Journal of Contemporary China 22 (84): 1048–1066.

Heimer, Maria. 2016. The Cadre responsibility system and the changing needs of the party. In The Chinese communist party in reform, ed. Kjeld Brødsgaard and Yongnian Zheng, 122–138. Abingdon: Routledge.

Helmke, Gretchen, and Steven Levitsky. 2004. Informal institutions and comparative politics: A research agenda. Perspectives on Politics 2 (4): 725–740.

Hendry, David. 1995. Dynamic econometrics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hu, Xiaobo, and Fanbin Kong. 2021. Policy innovation of local officials in China: The administrative choice. Journal of Chinese Political Science 26: 695–721.

Jaccard, James. 2001. Interaction effects in logistic regression. Sage Publications.

Jia, Ruixue, Masayuki Kudamatsu, and David Seim. 2015. Political selection in China: The complementary roles of connections and performance in political selection in China. Journal of the European Economic Association 13 (4): 631–668.

Jiang, Junyan. 2018. Making bureaucracy work: Patronage networks, performance incentives, and economic development in China. American Journal of Political Science 62 (4): 982–999.

Keller, Franziska. 2016. Moving Beyond Factions: Using Social Network Analysis to Uncover Patronage Networks Among Chinese Elites. Journal of East Asian Studies 16 (1): 17–41.

Kostka, Genia. 2016. Command without control: The case of China’s environmental target system. Regulation and Governance 10 (1): 58–74.

Kung, James, and Shuo Chen. 2011. The tragedy of the Nomenklatura: Career incentives and political radicalism during China’s great leap famine. American Political Science Review 105 (1): 27–45.

Landry, Pierre. 2008. Decentralized authoritarianism in China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Landry, Pierre, Xiaobo Lü, and Haiyan Duan. 2018. Does performance matter? Evaluating the institution of political selection along the Chinese Administrative Ladder. Comparative Political Studies 51 (8): 1074–1105.

Lee, Don, and Paul Schuler. 2020. Testing the ‘China Model’ of meritocratic promotion: Do democracies reward less competent ministers than autocracies. Comparative Political Studies 53 (3–4): 531–566.

Lewin, Moshe. 2003. Rebuilding the Soviet nomenklatura 1945–1948. Cahiers Du Monde Russe 44 (2): 219–252.

Li, Chen. 2012. Leadership transition in the CPC: Promising progress and potential problem. China: an International Journal 10 (2): 23–33.

Li, Jiayuan. 2015. The paradox of performance regimes: Strategies responses to target regimes in Chinese Local Government. Public Administration 93 (4): 1152–1167.

Li, Hongbin, and Li.-an Zhou. 2005. Political turnover and economic performance: The incentive role of personnel control in China. Journal of Public Economics 89: 1743–1762.

Lieberthal, Kenneth. 2003. Governing China, 2nd ed. W.W. Norton & Company.

Lust-Okar, Ellen. 2006. Elections under authoritarianism: Preliminary lessons from Jordan. Democratization 13 (3): 456–471.

Ma, Liang. 2013. Promoting incentive of government officials and government performance target-setting: An empirical analysis of provincial panel data in China. Gonggong Guanlixuebao 10 (2): 28–39 (in Chinese).

Magaloni, Beatriz. 2006. Voting for autocracy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Magaloni, Beatriz. 2008. Credible power-sharing and the longevity of authoritarian rule. Comparative Political Studies 41 (4/5): 715–741.

Manion, Melanie. 1985. The Cadre management system, post-Mao: The appointment, promotion, transfer and removal of party and state leaders. China Quarterly 102: 203–233.

Mccubbins, Mathew, and Michael Thies. 1997. As A matter of factions: The Budgetary implications of shifting factional control in Japan’s LDP. Legislative Studies Quarterly 22 (3): 293–328.

Meng, Tianguang, Jennifer Pan, and Ping Yang. 2017. Conditional receptivity to citizen participation: Evidence from a survey experiment in China. Comparative Political Studies 50 (4): 399–433.

Miller, Michael. 2015a. Electoral authoritarianism and human development. Comparative Political Studies 48 (12): 1526–1562.

Miller, Michael. 2015b. Elections, information, and policy responsiveness in autocratic regimes. Comparative Political Studies 48 (6): 691–727.

Nathan, Andrew, and Kellee Tsai. 1995. Factionalism: A new institutionalist restatement. The China Journal 34: 157–192.

Ning, Leng, and Cai Zuo. 2022. Tournament style bargaining within boundaries: Setting targets in China’s Cadre Evaluation System. Journal of Contemporary China 31 (133): 116–135.

O’Brien, Kevin, and Lianjiang Li. 1999. Selective policy implementation in rural China. Comparative Politics 31 (2): 167–186.

Pepinsky, Thomas. 2013. The institutional turn in comparative authoritarianism. British Journal of Political Science 44 (3): 631–653.

Rigby, T.H. 1970. The Soviet leadership: Towards a self-stabilizing oligarchy? Soviet Studies 22 (2): 167–191.

Rigby, T.H. 1988. Staffing USSR incorporated: The origins of the Nomenklatura System. Soviet Studies 40 (4): 523–537.

Shih, Victor. 2004. Factions matter: Personal networks and the distribution of bank loans in China. Journal of Contemporary China 13 (38): 3–19.

Shih, Victor. 2008a. Factions and finance in China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shih, Victor. 2008b. Nauseating displays of loyalty: Monitoring the factional bargain through ideological campaigns in China. Journal of Politics 70 (4): 1177–1192.

Shih, Victor, Christopher Adolph, and Mingxing Liu. 2012. Getting ahead in the communist party: Explaining the advancement of central committee members in China. American Political Science Review 106 (1): 166–187.

Svolik, Milan. 2012. The politics of authoritarian rule. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Tsai, Kellee. 2016. Adaptive informal institutions. In Oxford handbook of historical institutionalism, ed. Orfeo Fioretos, Tulia Falleti, and Adam Sheingate, 270–287. New York: Oxford University Press.

Walder, Andrew. 2004. The party elite and China’s trajectory of change. China: an International Journal 2 (2): 189–209.

Wang, Shaoguang. 2008. Changing models of China’s policy agenda setting. Modern China 34 (1): 56–87.

Wang, Zhen. 2021. The elusive pursuit of incentive systems: Research on the cadre management regime in post-Mao China. Journal of Chinese Political Science 26: 573–592.

Whiting, Susan. 2006. Power and wealth in rural China. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Willerton, John. 1987. Patronage networks and coalition building in the Brezhnev era. Soviet Studies 39 (2): 175–204.

Wong, Mathew. 2022. Performance, factions, and promotion in China: The role of provincial transfers. Journal of Chinese Political Science 27: 41–75.

Xi, Tianyang. 2019. All the emperor’s men? Conflicts and power-sharing in imperial China. Comparative Political Studies 52 (8): 1099–1130.

Zhu, Jiangnan, and Dong Zhang. 2017. Weapons of the powerful: Authoritarian elite competition and politicized anticorruption in China. Comparative Political Studies 50 (9): 1186–1220.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Melanie Manion, Pierre Landry, James Kung, Kellee Tsai, Edward Friedman, Xiaobo Lü, Ling Chen, Jean Hong, Xian Huang, and participants in the Chinese Political Workshop at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Peking University, and 2017 APSA conference for helpful comments. Financial support from Fudan University, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, and University of Wisconsin-Madison is gratefully acknowledged. All errors remain my own.

Funding

Sponsored by MOE (Ministry of Education in China) Project of Humanities and Social Sciences (Project No. 17YJCZH278).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zuo, C. Political Selection Institutions and Policy Performance: Evidence from China. Chin. Polit. Sci. Rev. 9, 129–151 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-022-00225-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-022-00225-5