Abstract

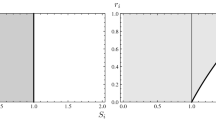

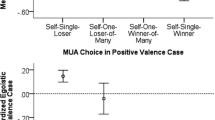

This paper formulates a model of conflict based on the theory of distributive justice. The model begins with a condition we termcleavage: There is a perfect correlation between the distribution of a valued good and a grouping variable such as race, ethnicity, or sex. Cleavage sets the stage for conflict. Two key elements are specified—conflict severity and subgroup effectiveness—and their mathematical representation described. The paper analyzes the special case where the conflict involves two subgroups, and focuses on conflict severity. Analysis identifies several sources of variability in conflict severity: the relative sizes of the two subgroups; whether the advantaged subgroup is the smaller or larger; whether the collectivity values personal attributes (such as noble birth or athletic skill) or instead values material possessions; and the extent and shape of inequality in the distribution of material possessions. Results indicate, among other things, that, in a collectivity which values personal attributes, the smaller is the disadvantaged subgroup, the greater is the conflict severity. In contrast, in a collectivity which values material wealth, the direction of the effect of subgroup relative size on conflict severity depends on the distributional form of the valued material possessions. Results also indicate that, for given subgroup relative size, conflict severity is higher the greater the inequality in the distribution of valued material possessions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Atkinson, A. B. (1970). On the Measurement of Inequality.J. Econ. Theory 2: 244–263.

Atkinson, A. B. (1975).The Economics of Inequality, Oxford, London.

Berger, J., Zelditch, M., Jr., Anderson, B., and Cohen, B. P. (1972). Structural aspects of distributive justice: A status-value formulation. In Berger, J., Zelditch, M., and Anderson, B. (eds.),Sociological Theories in Progress, Vol. 2, Houghton Mifflin, Boston, pp. 119–246.

Blau, P. M. (1977).Inequality and Heterogeneity: A Primitive Theory of Social Structure, Free Press, New York.

Campbell, N. R. (1921).What is Science? Dover, New York.

Coleman, J. S. (1990).Foundations of Social Theory, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Durkheim, E. (1893/1964).The Division of Labor in Society (G. Simpson, transl.), Free Press, New York.

Ebaugh, H. R. (1993). The growth and decline of Catholic religious orders of women worldwide: The impact of women's opportunity structures.J. Sci. Study Religion 32: 68–75.

Fararo, T. J. (1989).The Meaning of General Theoretical Sociology: Tradition and Formalization, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes.Hum. Rel. 7: 117–140.

Hechter, M. (1983).The Microfoundations of macrosociology, Temple University Press, Philadelphia, PA.

Hechter, M. (1992). The dynamics of secession.Acta Sociol. 35: 1–17.

Heckathorn, D. D. (1984). Mathematical theory construction in sociology: Analytic power, scope, and descriptive accuracy as trade-offs. In Fararo, T. J. (ed.),Mathematical Ideas and Sociological Theory: Current State and Prospects. A Special Issue of the Journal of Mathematical Sociology, Gordon and Breach, New York, pp. 77–105.

Homans, G. C. (1961/1974).Social Behavior: Its Elementary Forms, Rev. Ed., Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, New York.

James, W. (1891/1952).The Principles of Psychology, Britannica, Chicago.

Jasso, G. (1978). On the justice of earnings: A new specification of the justice evaluation function.Am. J. Sociol. 83: 1398–1419.

Jasso, G. (1980). A new theory of distributive justice.Am. Sociol. Rev. 45: 3–32.

Jasso, G. (1982). Measuring inequality by the ratio of the geometric mean to the arithmetic mean.Sociol. Methods and Res. 10: 303–326.

Jasso, G. (1983). Social consequences of the sense of distributive justice: Small-group applications. In Messick, D. M., and Cook, K. S. (eds.),Theories of Equity: Psychological and Sociological Perspectives, Praeger, New York, pp. 243–294.

Jasso, G. (1986). A new representation of the just term in distributive-justice theory: Its properties and operation in theoretical derivation and empirical estimation.J. Math. Sociol. 12: 251–274.

Jasso, G. (1987). Choosing a good: Models based on the theory of the distributive-justice force.Adv. Group Proc.: Theory Res. 4: 67–108.

Jasso, G. (1988a). Distributive justice effects of employment and earnings on marital cohesiveness: An empirical test of theoretical predictions. In Webster, M. and Foschi, M. (eds.),Status Generalization: New Theory and Research, Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA, pp. 123–162, 490–493.

Jasso, G. (1988b). Principles of theoretical analysis.Sociol. Theory 6: 1–20.

Jasso, G. (1989a). Notes on the advancement of theoretical sociology (Reply to Turner).Sociol. Theory 7: 135–144.

Jasso, G. (1989b). Self-interest, distributive justice, and the income distribution: A theoretical fragment based on St. Anselm's postulate.Soc. Justice Res. 3: 251–276.

Jasso, G. (1989c). The theory of the distributive-justice force in human affairs: Analyzing the three central questions. In Berger, J., Zelditch, M., Jr., and Anderson, B. (eds.),Sociological Theories in Progress: New Formulations, Sage, Newbury Park, CA, pp. 354–387.

Jasso, G. (1990). Methods for the theoretical and empirical analysis of comparison processes. In Clogg, C. C. (ed.),Sociol. Methodol, American Sociological Association, Washington, DC.

Jasso, G. (1991). Cloister and society: Analyzing the public benefit of monastic and mendicant institutions.J. Math. Sociol. 16: 109–136.

Jasso, G. (1993). Choice and emotion in comparison theory.Rational. Soc. 5: 231–273.

Jasso, G., and Rossi, P. H. (1977). Distributive justice and earned income.Am. Sociol. Rev. 42: 639–651.

Johnson, N. L., and Kotz, S. (1969).Distributions in Statistics: Discrete Distributions, Wiley, New York.

Johnson, N. L., and Kotz, S. (1970a).Distributions in Statistics: Continuous Univariate Distributions—1, Wiley, New York.

Johnson, N. L., and Kotz, S. (1970b).Distributions in Statistics: Continuous Univariate Distributions—2, Wiley, New York.

Lakatos, I. (1970). Falsification and the methodology of scientific research programmes. In Lakatos, I., and Musgrave, A. (eds.),Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., pp. 91–95.

Marx, K. (1849/1968). Wage labour and capital. InKarl Marx and Frederick Engels: Selected Works, International Publishers, New York, pp. 74–97.

Marx, K. (1859/1913).A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, Kerr, Chicago.

Merton, R. K. (1945). Sociological theory.Am. J. Sociol. 50: 462–473.

Merton, R. K., and Rossi, A. S. (1950). Continuities to the theory of reference group behavior. In Merton, R. K., and Lazarsfeld, P. (eds.),Continuities in Social Research: Studies in the Scope and Method of “The American Soldier”, Free Press, New York, pp. 40–105.

Moses, L. E. (1968). Statistical analysis: Truncation and censorship. In Sills, D. L. (ed.),International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, Vol. 15 Macmillan, New York, pp. 196–201.

Newton, I. (1686/1934).Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy (A. Motte, transl., F. Cajori, rev.), Britannica, Chicago.

Rawls, J. (1971).A Theory of Justice, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Sheehan, N. (1991).After the War Was Over: Hanoi and Saigon, Random House, New York.

Stouffer, S. A., et al. (1949).The American Soldier. Two volumes. Studies in Social Psychology in World War II. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

World Bank. (1990).World Tables 1990, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jasso, G. Analyzing conflict severity: Predictions of distributive justice theory for the two-subgroup case. Soc Just Res 6, 357–382 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01050337

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01050337