Abstract

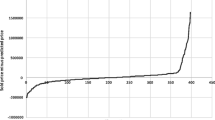

In the real estate market the seller/agent relationship changes over the course of the listing contract. As the contract expiration nears, brokers may increase efforts generating more potential buyers and, perhaps, a higher offered price. Brokers may also persuade the seller to reduce the reservation price. These two aspects have different implications for the selling price of the property. Employing a sample of 24,100 properties sold in Clark County, Nevada, we investigate the relationship between the selling price and the time-to-expiration of the listing contract. We find that prices are lower if the property is sold near the expiration of the listing contract, indicating that the price-reduction effect dominates the broker-effort effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We use the words agent and broker interchangeably, meaning a licensed real estate person who signs a listing contract with a seller.

With a consignment sale the seller agrees to a minimum price and the broker receives the difference between that amount and the actual sales price.

Several articles, while not directly dealing with principal–agent issues related to efforts and reservation prices, implicitly consider the role of commission rates, broker effort, and broker-related factors on the TOM. For examples see Yavas and Yang (1995), Yang and Yavas (1995), Springer (1996), and Jud et al. (1996).

The samples are from MLS, and it is not clear whether the broker-owner is also the agent who found the buyer of the property.

In addition, it is possible that many broker-owned properties were initially purchased for investment purposes. Broker investors have an information advantage relative to nonbroker investors. It is possible that brokers buy properties with, or added, characteristics that are unobserved in the datasets but are valued by potential future buyers and, thus, broker-owned houses may sell for more. In fact, Table 2 of the study of Rutherford et al. shows that owner–brokers listed several of their own properties at the same time. This is an indication of real estate investment activities.

In a departure from previous research we do not use the transaction price of the property. Our data include the seller contribution to closing costs (if any). We deduct from the transaction price the amount of any seller contribution to arrive at a “net” price.

It can be shown that the size of the potential bias from omitting TTE equals \( \beta _{{\operatorname{TTE} }} {\left[ {{Cov{\left( {TOM,TTE} \right)}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{Cov{\left( {TOM,TTE} \right)}} {Var{\left( {TOM} \right)}}}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {Var{\left( {TOM} \right)}}} \right]} < 0 \). The search theory predicts \( \beta _{{\operatorname{TOM} }} > 0 \). The agency problem predicts \( \beta _{{\operatorname{TOM} }} > 0 \). The covariance of TOM and TTE is expected to be negative. Thus, if the true value of \( \beta _{{TOM}} > 0 \), then omission bias will cause underestimation. If the true value of \( \beta _{{TOM}} < 0 \), then the omission bias will overstate the negative size of the coefficient. We thank an anonymous referee of the journal for raising the question of the potential bias.

In the empirical analysis section for ease of interpretation, we divide all duration variables by 30, so the estimated coefficients are per 30 days.

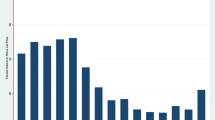

As was pointed out by the referee, separation of the TOM and the brokerage effort effects requires that there is sufficient variation in listing contract duration across the observations. The sample information in Table 1 shows a mean of 163 and a standard deviation of 70 days. The range and inter-quartile range are 720 and 60 days, respectively. The range for the middle 80% of observations is about 120 days.

The Las Vegas housing market experienced a “hot market” bubble similar to the national trend from 2003 to late 2004/early 2005. Discussions with local real estate agents indicate that the time period selected for our study was subsequent to the “seller’s market.” In our sample 66.5% of the properties sold for less than the list price. One would expect few properties to sell at a discount from list price in a “seller’s market.”

We eliminated all condominiums and single-family properties with a sales price less than $100,000 or greater than $2,000,000, price per square foot less than $100 or greater than $500, lot square feet below 1,200 or above 45,000, and building square feet below 800 or above 4,000.

The total commission rate that is a part of the listing contract is not provided by GLVAR. However, the Las Vegas real estate market during the period under consideration was relatively stable and there was not much variation in the total commission rate.

The GLVAR was not able to provide information on the year a broker joined the organization. However, they did confirm that the ID number is assigned chronologically as members joined. And, of course, some brokers could have easily had experience previous to joining the GLVAR. Given the limitations of this variable we are of the opinion that some information is better than none.

The market condition information comes from the data that are collected and analyzed by the Center for Business and Economic Research at UNLV.

The error terms in price and TOM equations are correlated. Thus, in the first-stage, each endogenous variable is predicted using all exogenous variables in the system. In the second stage, the predicted values of the endogenous variable as well as other relevant exogenous variables are included as explanatory variables in each equation (i.e., predicted values of TOM for the price equation and predicted values of the price for the TOM equation). Residuals from the second stage are used to obtain a consistent estimate of the covariance matrix of the two disturbances. Using the consistent estimate of the covariance matrix and generalized least squares (GLS), we estimate the parameters of the system of the two equations. See Green (2003, pp. 404–407).

Based on Hausman’s specification test, the null hypothesis that the difference in coefficients across the two specifications in columns 1 and 2 is not systematic is rejected, an indication of the statistical significance of the bias.

References

Anglin, P. M., & Arnott, R. (1991). Residential real estate brokerage as a principal–agent problem. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 4, 99–125.

Arnold, M. A. (1992). The principal–agent relationship in real estate brokerage services. Real Estate Economics, 20, 89–106.

Geltner, D., Kluger, B. D., & Miller, N. G. (1991). Optimal price and selling effort from the perspectives of the broker and seller. Real Estate Economics, 19, 1–24.

Green, W. H. (2003). Econometrics analysis. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Haurin, D. (1988). The duration of marketing time of residential housing. Real Estate Economics, 16, 396–410.

Jud, G. D., Seaks, T. G., & Winkler, D. T. (1996). Time on the market: The impact of residential brokerage. Journal of Real Estate Research, 12, 447–458.

Larsen, J. E., & Park W. J. (1989). Non-uniform percentage brokerage commissions and real estate market performance. Real Estate Economics, 17, 422–438.

Rutherford, R. C., Springer, T. M., & Yavas, A. (2005). Conflicts between principals and agents: Evidence from real estate brokerage. Journal of Financial Economics, 76, 627–665.

Sirmans, C. F., Turnbull, G. K., & Benjamin, J. D. (1991). The markets for housing and real estate broker services. Journal of Housing Economics, 1, 207–217.

Springer, T. M. (1996). Single-family housing transactions: Seller motivations, price, and marketing time. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 13, 237–254.

Williams, J. (1998). Agency and brokerage of real estate assets in competitive equilibrium. Review of Financial Studies, 11, 239–280.

Yang, X., & Yavas, A. (1995). Bigger is not better: Brokerage and time on the market. The Journal of Real Estate Research, 10, 23–33.

Yavas, A., & Yang, X. (1995). The strategic role of listing price in marketing real estate: Theory and evidence. Real Estate Economics, 23, 347–368.

Zorn, T. S., & Larsen, J. E. (1986). The incentive effects of flat-fee and percentage commissions for real estate brokers. Real Estate Economics, 14, 24–47.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank an anonymous referee of the journal, Saeyoung Chang, Stephen Miller, Paul Thistle, and Bradley Wimmer for their comments and suggestions. We also wish to thank the Lied Institute for real Estate Studies at UNLV for financial support of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This paper was recognized as the best 2007 paper in Real Estate Brokerage/Agency by the Center for the Study of Real Estate Brokerage/Agency at Cleveland State University.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Clauretie, T.M., Daneshvary, N. Principal–Agent Conflict and Broker Effort Near Listing Contract Expiration: The Case of Residential Properties. J Real Estate Finance Econ 37, 147–161 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-007-9045-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-007-9045-7