Abstract

The two brothers Julius and Adolf Hurwitz were born in the middle of the nineteenth century in a small town near Hanover (not far from Göttingen). Already during their schooldays, the two of them became acquainted with mathematical problems and both started to study mathematics, but while the younger brother Adolf turned out to be extremely successful in his research, the elder brother and his work seem to be almost forgotten. This paper examines the lives and works of the two brothers with particular emphasis on the contributions of Julius Hurwitz, and the subsequent reception of their research. It deals with the development of an arithmetical theory for complex continued fractions by Julius and Adolf Hurwitz around 1890 and its rediscovery in the twentieth century.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The common Jewish surname Hurwitz (as well as Horowitz and Hurewicz) is a reference to the historically portentous small town Hořovice in Central Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic.

Those certificates of the Realgymnasium Andreanum in Hildesheim can be found in the municipal archive of Hildesheim (cf. Rasche 2011, Appendix).

Chasles’ theorem allows one to count the number of curves satisfying certain algebraic conditions within a family of conics; it generalizes Bézout’s theorem and plays a significant role in algebraic geometry. Schubert developed a calculus in order to solve counting problems of such type (1879), and Hilbert’s problem number 15 asks for a rigorous justification of Schubert’s enumerative calculus.

There is a photograph of the father with his three boys in Rowe (2007, 20).

This is the authors’ translation from the German original: “Ebenso legte er auch Wert darauf, dass die Knaben schon sehr frühzeitig zu rauchen begannen, da ihm ein rechter Mann ohne Cigarre oder besser noch Pfeife kaum denkbar war” (Hurwitz-Samuel 1984, 2). If not indicated differently, all translations from German to English have been made by the authors.

“Schubert suchte sogar den Vater auf, um ihn zu bestimmen, beide Söhne das Studium der Mathematik ergreifen zu lassen” (Hurwitz-Samuel 1984, 4).

There are postcards from June 17, 1881, and September 4, 1881, from Salomon to Julius in Hamburg, courtesy of the archive of the ETH Zürich (ISIL-Code: CH-000003-X Fonds-Hurwitz-A).

At that time, this institution was called Königlich Bayerische Technische Hochschule München; since 1970, it is the Technische Universität München.

Since 1949 the University of Berlin has been called the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

An excerpt of a letter from Klein to Adolf Hurwitz’s father explaining the situation and the prospects for his son can be found in Rowe (2007, 22).

According to his later wife Hurwitz-Samuel (1984, 6), he had to borrow a tailcoat from a fellow student for his doctoral viva.

“Seitdem ist das Interesse für Riemanns Funktionentheorie in immer weiteren Kreisen, auch des Auslandes, erwacht. Von meinen Schülern ist wohl besonders Hurwitz in Zürich und Dyck in München zu nennen” (Klein 1926, 276).

In the German system Habilitation granted the “venia legendi,” i.e., the permission to lecture as a Privatdozent which at that time meant to collect course fees from the students without any payment from the university. For more details on exploiting scientists and the academic ladder in nineteenth century Germany see Rowe (1986).

“An der lebhaften Göttinger Geselligkeit nahm H. auch sonst eifrig teil, so schwang er das Tanzbein bei dem grossen Physiker Wilh. v. Weber,...” (Hurwitz-Samuel 1984, 7).

Nowadays Kaliningrad in Russia.

Neue Darstellung des Weierstrass’schen Beweises für die Transzendenz von \(e\) und \(\pi \), enclosed in Adolf Hurwitz’s mathematical diaries: Mathematisches Tagebuch 3, 9 January 1883—ca. 1884; Hs 582:3 (Hurwitz 1972, 118–125).

“Es ist ein ordentliches Ereignis, und wir können der Vorsehung nicht genug danken, daß unser Adolf so begabt, so beliebt und schon von den bedeutendsten Mathematikern als ein hervorragender Mensch anerkannt wird.” Letter from Salomon to Julius, April 1, 1884, courtesy of the ETH library (ISIL-Code: CH-000003-X Fonds-Hurwitz-A).

“Seit dem Tode Onkel Adolphs waren Max u. Julius Inhaber des Bankgeschäfts ‘Adolph M. Wertheimer’s Nachf.’ in Hannover, fühlten sich aber im Kaufmannstande nicht glücklich. So trat zuerst Julius aus, setzte sich mit 33 Jahren nochmals auf die Schulbank, um das Abiturientenexamen nach zumachen und dann bei seinem jüngeren Bruder Mathematik zu studieren” (Hurwitz-Samuel 1984, 8).

The certificate including several grades can still be found in the archive of Halle University (Rep. 21 Nr. 162).

“[Adolf] Hurwitz lässt Sie bestens grüssen. Augenblicklich ist auch sein ältester Bruder hier bei ihm zum Besuch.”, letter 63 in Frei (1985, 73); actually, Max was the eldest, and Julius the second.

“Grüße bestens die Gebrüder Hurwitz und die anderen Königsberger Mathematiker [...]”, in (Rüdenberg and Zassenhaus (1973), 45).

Those notes can still be found in the archives of the ETH Zürich (Hs 582: 52–53; 64–65; 96).

1864–1951; author of a brief and very readable account (Hurwitz-Samuel 1984) on the Hurwitz family and her husband in particular.

Stern died in 1894. Adolf Hurwitz and his colleague Ferdinand Rudio, a colleague from ETH and former friend from his study times at Berlin, published the collected letters from Eisenstein to Stern (Hurwitz and Rudio 1894); this had been a wish of Stern and it affirms his close relation with Adolf Hurwitz.

“[Auch] sein Bruder Julius folgte ihm bald nach Zürich, wo er an der Doktorarbeit schrieb, deren Thema er von seinem Bruder erhalten hatte” (Hurwitz-Samuel 1984, 9).

“Viros audivi illustrissimos: [...] Turici: Franel, Geiser, Hurwitz, Rudio, A. Stadler, Stern, von Wyss, Fr. Weber” (Hurwitz 1895, 50).

Usually, dissertation projects were officially ratified at the University of Zurich until the ETH obtained full rights to supervise doctoral students independently in 1909; anyway, the relation between Julius and Adolf might have been too close.

Schubert wrote his dissertation on enumerative geometry during his studies in Berlin, however, after the death of his teacher Gustav Magnus, he decided to finish his doctorate at the University of Halle without official supervisor; see Burau and Renschuch (1993) for further details.

See www.mathematikuni-halle.de/history for a list.

“Im Sommer 1888 verbrachte er [Adolf Hurwitz] auf Anregung von Prof. Mittag-Leffler in Stockholm, einige Tage in Wernigerode i/H. in interessantem mathematischen Kreis der sich um den Altmeister Prof. Weierstrass aus Berlin geschart hatte. Dort lernte er Georg Cantor und Sonja Kowalewski näher kennen” (Hurwitz-Samuel 1984, 8).

“Für die freundliche Aufnahme der Notiz meines Schülers Hurwitz besten Dank.”, cf. Décaillot (2011, 152).

“Meinem lieben Bruder und verehrten Lehrer Herrn Prof. Dr. A. Hurwitz”.

“Es sei mir gestattet, meinem Lehrer, Herrn Professor A. Hurwitz, für die mannigfachen Ratschläge, mit welchen er mich bei dieser Arbeit unterstützt hat, auch an dieser Stelle meinen herzlichsten Dank auszusprechen.” Rep. 21 Nr. 162, Universitätsarchiv Halle-Wittenberg, Halle.

“Herr J. Hurwitz untersucht im Anschluß an eine in den Acta mathematica, Band XI, veröffentlichte Arbeit seines Bruders, des Prof. A. Hurwitz in Zürich, eine besondere Art der Kettenbruchentwickelung complexer Größen.” Announcement of the disputation by A. Wangerin, Rep. 21 Nr. 162, Universitätsarchiv Halle-Wittenberg, Halle.

“Der Verfasser untersucht in der vorliegenden Arbeit eine besondere Art der Kettenbruchentwickelung complexer Grössen nach ähnlichen Gesichtspunkten, wie sie der Referent der Behandlung gewisser anderer Kettenbruchentwickelungen reeller und complexer Grössen [...] zu Grunde gelegt hat.”

Mathematisches Tagebuch 9, 4 April 1894–15 January 1895; Hs 582:9 (Hurwitz 1972, 99–107).

“Die Durchführung der Untersuchung zeugt nicht nur von Fleiß und tüchtiger mathematischer Schulung, sondern auch von selbständigem Nachdenken.” Gutachten der Dissertation von A. Wangerin, Rep. 21 Nr. 162, Universitätsarchiv Halle-Wittenberg, Halle.

Gutachten der Dissertation, Rep. 21 Nr. 162, Universitätsarchiv Halle-Wittenberg, Halle.

Personal file, Dozentenkartei, Universitätsarchiv F 6.2.1, Staatsarchiv Basel.

“Der Petent hat sich in kurzer Zeit mit Eifer und Geschick in das Gebiet der Mathematik eingearbeitet,” protocols of the sessions of the philosophical faculty, StABS, Universitätsarchiv R 3.5 Basel

The Swiss version of the “venia legendi.”

“Hochgeachteter Herr, auf Antrag der philosophischen Fakultät hat E. E. Regenz in ihrer gestrigen Sitzung beschlossen, Herrn Dr. phil Julius Hurwitz die venia docendi für Mathematik zu verleihen. Herr Hurwitz hat sich durch eine Habilitationsschrift und durch ein Colloquium in der Weise ausgewiesen, daß Fakultät und Regenz überzeugt sind, daà in ihm unserer Universität eine tüchtige Kraft gewonnen wird.” Extract from the application of the ‘Venia docendi’, Erziehungsakten CC 28b, Staatsarchiv Basel.

Protocols of the sessions of the philosophical faculty, StABS, Universitätsarchiv R 3.5 Basel.

For example, over the appointment of Minkowski; see letter 107 from Hilbert to Klein in Frei (1985, 122).

“der Herr Professor darüber ein wenig verwundert gewesen sei, war doch dieser Student niemals in den mathematischen Seminaren zu sehen gewesen, da er sich mangels an Zeit nicht beteiligen konnte. (...) dass es für einen Physiker genüge, die elementaren mathematischen Begriffe zu kennen und anzuwenden, der Rest für ihn aus ’unfruchtbaren Subtilitäten’ bestehe” (Fölsing 1993, 634).

A nice photograph illustrating such a performance can be found in Pólya (1987, 24).

Adolf Hurwitz had previously supported the forerunner of the ICM at Chicago’s World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893 by submitting a contribution in absentia; see Lehto (1998, 5), resp. www.mathunion.org/ICM/.

In German: Gesellschafter.

“[...] war Julius nach langer Pause wieder einmal bei uns zu Besuch (er war seinem Gesellschafter Franz Sieckmeyer nach Freiburg i/Br. gefolgt, wo dieser Lazarettdienst leistete). Auch Julius war seit Jahren sehr leidend (Herzleiden und Arterienverkalkung), auch machte bei diesem letzten Zusammensein, auf welches beide Brüder wohl kaum mehr gerechnet hatten, Adolf den weitaus kränklicheren Eindruck.“ (Hurwitz-Samuel 1984, 13)

Pólya (1987, 25) wrote “His health was not too good so when we walked it had to be on level ground, not always easy in the hilly part of Zürich, and if we went uphill, we walked very slowly.” Pólya at that time was around 30 years old whereas Adolf in the mid-fifties.

Alphabetische Ausländerkontrolle, F8/7:10, Stadtarchiv Luzern.

“Am 15. Juni schloss Julius in Luzern bei einem der häufigen Herzanfälle, die er erlitt, ganz plötzlich seine Augen für immer. [Adolf] H. nahm die Nachricht, die ihm mit größter Vorsicht beigebracht wurde, voll Ergebung auf, das Geschick des Bruders preisend, der nun alles überstanden habe, und für sich selber das Gleiche ersehnend.“ (Hurwitz-Samuel 1984, 13)

“[wir,] an der Tür Lauschenden bewunderten die Beherrschtheit und Klarheit, mit der er vorzutragen vermochte.“ (Hurwitz-Samuel 1984, 14)

The family grave in field D had number 81201; the grave was removed in 2000.

In Pólya (1987, 25), George Pólya wrote: “My connection with Hurwitz was deeper and my debt to him greater than to any other colleague.” It was indeed on Adolf Hurwitz’s invitation that Pólya was offered an appointment as Privatdozent at Zurich.

According to the Mathematics Genealogy Project http://genealogy.math, all within the period 1896–1919; however, in his collected works (Hurwitz 1932, 754, vol. II) there are just 21 listed. Among his pupils one can find the later professors Gustave du Pasquier at the Université de Neuchâtel, Eugène Chatelain, Alfred Kienast, Émile Marchand, and Ernst Meissner, all at ETH Zurich, as well as Kerim Erim, who obtained his doctorate at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg and later became a professor at the University of Istanbul.

It is interesting to notice that he was also an honorary member of the mathematical societies of Hamburg and Kharkov, and a corresponding member of the Academia di Lincei at Rome (which is rather different from the image of a couch potato that one could have in view of his absence from International Congresses outside Zurich).

For details about the various appearances of continued fractions in ancient Greek mathematics we refer to Fowler (1990).

See Stedall’s (2000) articles for more details.

“Die Theorie der Kettenbrüche, deren Zähler durchgehends Einheiten, deren Nenner ganze algebr. Zahlen sind spielen sowohl im funktionen- wie zahlentheoretischer Hinsicht eine bemerkenswerte Rolle. Im Falle der Zahlen \(a+bi\) und \(a+b\rho \) (\(i=\sqrt{-1}, \rho ={-1+i\sqrt{3}\over 2}\)) ist, wegen der Möglichkeit des Euklid. Verfahrens zur Bestimmung des größten gemeins. Theilers, die Entwickl. der betreffenden Theorie ohne prinzipielle Schwierigkeiten. Nichts desto weniger scheint eine sorgfältige und gründliche Durchführung derselben von großem Werte, z.B. für die Lösung Diophant. Gleichungen des zweiten Grades für die betr. Zahlengebiete. Dieses ist eine gute Doctor-Arbeit für einen jüngeren strebsamen Mathematiker.” (Hurwitz 1972, 16), Mathematisches Tagebuch 1, 25.04.1882–09.04.1884; Signatur Hs. 582:1.

According to his mathematical diary no. 5, February 1886–March 1888, pp. 49–69; Hs 582:5 (Hurwitz 1972, 49–69). Unfortunately, there is no date attached, but a later entry has date May 1, 1887.

In modern mathematical language this convergent expansion is obtained by iteration of the mapping \(x\mapsto Tx:=T(x):={\epsilon \over x}-\left\lfloor {\epsilon \over x}\right\rfloor \) for \(x\ne 0\) and \(T0=0\), where \(\lfloor z\rfloor \) denotes the integer part of \(z\) (which is unique provided \(z-{1\over 2}\not \in \mathbb {Z}\)); here, the subsequent partial quotients are given by \(a_n:=\lfloor T^{n-1}\vert x\vert \rfloor \) and the sign \(\epsilon _n=\epsilon \) equals the sign of \(T^{n-1}\vert x\vert \). The first iteration leads to

$$\begin{aligned} x={\epsilon _1\over \lfloor {\epsilon _1\over x}\rfloor +T\vert x\vert }={\epsilon _1\over a_1} + {\epsilon _2\over a_2+T^2\vert x\vert } \end{aligned}$$and so forth.

“Eine Theorie solcher Zahlsysteme ist in den bekannten Arbeiten von Kronecker und Dedekind, vorzugsweise für den Fall algebraischer Zahlen entwickelt. Vgl. insbesondere das XI. Supplement zu Dirichlet’s Vorlesungen über Zahlentheorie. Dritte Auflage” (Hurwitz 1888, 187).

“Ausser der hier betrachteten giebt es übrigens noch andere Kettenbruchentwicklungen im Gebiete der complexen Zahlen \(m+ni\), für welche der obige Satz ebenfalls gilt, worauf ich indessen an dieser Stelle nicht eingehen will.”

“Neben Klein, dessen Vorlesungen über seine Forschungen im Gebiet der Modulfunktionen ihn in hohem Masse fesselten, hörte er bei Gustav Bauer, Seydel, Pringsheim, Brill und Beetz. Bauer u. Pringsheim trat er persönlich näher \(\ldots \)” (Hurwitz-Samuel 1984, 6); probably, Seydel is misspelled here.

In German: ‘Kettenbrüche zweiter Art’.

To explain that we recall Nakada’s \(\alpha \)-continued fraction from Nakada (1981). Given a fixed real number \(\alpha \in [{1\over 2},1]\), the \(\alpha \)-continued fraction of a real number \(x\in I_\alpha :=[\alpha -1,\alpha )\) is a convergent finite or infinite semi-regular continued fraction of the form \(x={\epsilon _1\over a_1} + {\epsilon _2\over a_2} + \cdots + {\epsilon _n\over a_n} + \cdots \), where the partial quotients \(a_n\) are positive integers and the \(\epsilon _n=\pm 1\) are signs determined by iterations of the transform \(T_\alpha \) on \([\alpha -1,\alpha )\) given by \(T_ \alpha (0)=0\) and \(T_\alpha (x):={1\over \vert x\vert }-\Big \lfloor {1\over \vert x\vert }+1-\alpha \Big \rfloor \) otherwise. For \(\alpha =1\) Nakada’s \(\alpha \)-continued fraction expansion is nothing but the regular continued fraction, for \(\alpha ={1\over 2}\) one obtains the continued fraction to the nearest integer, and for \(\alpha ={\sqrt{5}-1\over 2}\) it is the singular continued fraction due to Adolf Hurwitz (1889).

See Cassels’ (1957) monograph for further information.

“Ein mit Vorliebe von Hurwitz behandeltes Thema war die Theorie der arithmetischen Kettenbrüche. In seiner Arbeit ’Über die Entwicklung komplexer Größen in Kettenbrüche’ ging er dabei über den bisher allein berücksichtigten Bereich der reellen Zahlen hinaus und stellte einen allgemeinen Satz über die Periodizität der Kettenbruchentwicklung relativ quadratischer Irrationalitäten auf, der auf die Kettenbruchentwicklungen in den Körpern der dritten und vierten Einheitswurzeln eine interessante Anwendung findet” (Hilbert 1921, 163).

“Und glücklicherweise findet sich um 1885 für fast wieder ein Jahrzehnt, eben auch wieder in Königsberg, ein Dreibund junger Forscher zusammen, welche diese Tendenz in neuer Weise in die Tat umsetzen und damit denjenigen Standpunkt schaffen, von dem aus die Neuzeit, wenn sie es vermag, weiterzugehen hat. Es sind dies Hurwitz, Hilbert und Minkowski. (...) und so möchte ich über Hurwitz und Minkowski hier vorweg ein paar Worte sagen, welche deren Arbeitsweise charakterisieren sollen. Man hat Hurwitz einen Aphoristiker genannt. In voller Beherrschung der in Betracht kommenden Disziplinen sucht er sich hier und dort ein wichtiges Problem heraus, das er jeweils um ein bedeutendes Stück fördert. Jede seiner Arbeiten steht für sich und ist ein abgeschlossenes Werk. (...) Minkowskis hier in Betracht kommende Arbeiten beruhen zumeist auf der Verbindung durchsichtiger geometrischer Anschauung mit zahlentheoretischen Problemen. (...) Ich selbst habe mich seinerzeit darauf beschränkt, gewisse schon bekannte Grundlagen geometrisch klarzustellen, während Minkowski Neues zu finden unternahm. Diese Untersuchungen zeigen deutlich, daß Geometrie und Zahlentheorie keineswegs einander ausschließen, sofern man sich in der Geometrie nur entschließt, diskontinuierliche Objekte zu betrachten” (Klein 1926, 326).

“Die Arbeit schliesst sich, nach Ziel und Methode, eng an die nachstehend genannten zwei Abhandlungen des Herrn A. Hurwitz an, dem ich auch die Anregung zu dieser Untersuchung verdanke.”

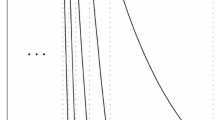

“Die complexe Zahlenebene werde durch die Geraden \(x+y=v, x-y=v\), wo alle positiven und negativen ungeraden ganzen Zahlen durchläuft, in unendlich viele Quadrate eingeteilt. Die Mittelpunkte dieser Quadrate werden durch die durch \(1+i\) teilbaren ganzen complexen Zahlen besetzt. Wenn nun \(x\) eine beliebige complexe Zahl ist, so bilde man die Gleichungskette:

$$\begin{aligned} x=a-{1\over x_1},\quad x_1=a_1-{1\over x_2},\ldots ,\quad x_n=a_n-{1\over x_{n+1}},\ldots \end{aligned}$$(1)nach der Massgabe, dass allgemein \(a_i\) den Mittelpunkt desjenigen Quadrates bezeichnet, in welches der Punkt \(x_i\) hineinfällt. Dabei sind noch bezüglich des Falles, wo \(x_i\) auf den Rand eines Quadrates fällt, besondere Festsetzungen getroffen, die wir der Kürze halber übergehen. Durch die Gleichungskette (1) wird nun für \(x\) eine bestimmte Kettenbruchentwickelung \(x=(a,a_1,\ldots ,a_n,x_{n+1})\) gegeben, deren nähere Untersuchung der Gegenstand der Arbeit ist.”

Actually, each iteration is determined by the transform \(T\) which is defined by \(T(0)=0\) and \(T(x):=\frac{1}{x}-[\frac{1}{x}]\) otherwise, in analogy with the approach of his younger brother; here the bracket \([x]\) is given by \([x]:=\big \lfloor u+{1\over 2}\big \rfloor \alpha +\big \lfloor v+{1\over 2}\big \rfloor \overline{\alpha }\qquad \text{ for }\quad x=u\alpha +v\overline{\alpha }\) with \(\alpha =1+i\), and \(T\) maps the square \(X:=\big \{x=u\alpha +v\overline{\alpha }\,:\,-{1\over 2}\le u,v<{1\over 2}\big \}\) onto \(X\). What turns up is an expansion of a unique complex continued fraction \(x=a_0+\frac{1}{a_1} + \frac{1}{a_2} + \frac{1}{a_3 + T^3x}\). This is modern notation and is different from what can be found in Julius’ dissertation Hurwitz (1895).

“Die Kettenbruch-Entwicklung erster Art einer complexen rationalen Zahl endigt dann und nur dann mit einem nicht durch \(1+i\) teilbaren Teilnenner, wenn, nach Forthebung gemeinsamer Faktoren, weder der Zähler noch der Nenner der Zahl durch \(1+i\) teilbar sind” (Hurwitz 1895, 27/28; Hurwitz 1902, 246).

A short algebraic proof goes as follows. The set of Gaussian integers is a disjoint union of the principal ideal \((\alpha )=(1+i)\mathbb {Z}[i]\) and \(1+(\alpha )\). Denoting the Julius Hurwitz-continued fraction of a complex number \(x\) by \(x=[a_0,a_1,\ldots ,a_n,\ldots ]\) the numerators \(p_n\) and denominators \(q_n\) of its convergents \({p_n\over q_n}=[a_0,a_1,\ldots ,a_n]\) satisfy the following recursion formulae:

$$\begin{aligned} \left\{ \begin{array}{c@{\quad }c} p_{-1}=\alpha ,\ p_0=a_0,&{} \mathrm{and}\qquad p_n=a_np_{n-1}+p_{n-2},\\ &{}\\ q_{-1}=0,\ q_0=\alpha , &{} \mathrm{and}\qquad q_n=a_nq_{n-1}+q_{n-2}. \end{array}\right. \end{aligned}$$The proof is analogous to the one for regular continued fractions, and only the initial values differ. To continue, we rewrite the recursion formulae in terms of \(2\times 2\)-matrices as

$$\begin{aligned} \left( \begin{array}{cc} p_n &{} p_{n-1} \\ q_n &{} q_{n-1}\end{array}\right) =\left( \begin{array}{cc} 0 &{} \alpha \\ \alpha &{} 0\end{array}\right) \left( \begin{array}{cc} a_1 &{} 1 \\ 1 &{} 0\end{array}\right) \ldots \left( \begin{array}{cc} a_n &{} 1 \\ 1 &{} 0\end{array}\right) \qquad (n\in \mathbb {N}_0). \end{aligned}$$After reducing the convergents \({p_n\over q_n}\) with respect to common powers of \(\alpha \) in the numerator and denominator, it follows from the recurrence formuale that

$$\begin{aligned} \left( \begin{array}{cc} p_{n+1} &{} p_n \\ q_{n+1} &{} q_n\end{array}\right) \equiv \left( \begin{array}{cc} 0 &{} 1 \\ 1 &{} 0\end{array}\right) ^n\ \hbox {mod}\, \alpha , \end{aligned}$$where the congruence is with respect to each entry. Hence, comparing the first columns on both sides, we have shown that each finite Julius Hurwitz-continued fraction is of the form predicted by the theorem. To show the converse, one may use Fermat’s descent method.

In Perron (1913, 186, vol. I), 3rd ed., Perron writes “Eine andere Vorschrift für die Wahl der Teilnenner stammt von J. Hurwitz (...); sie bildet das Analogon zu den halbregelmäßigen Kettenbrüchen mit geraden Teilnennern.” Actually, Julius Hurwitz-continued fractions of real numbers are exactly continued fractions with even partial quotients.

“Denkt man sich die durch \(1+i\) teilbaren ganzen complexen Zahlen \(a, a_1,\ldots , a_n\) und die complexe Grösse \(x_{n+1}\) willkürlich gewählt, so wird der Kettenbruch \((a,a_1,\ldots ,a_n,x_{n+1})\) durch seine Einrichtung eine bestimmte complexe Grösse x ergeben. Dieser Kettenbruch braucht aber nicht notwendig mit der nach obigem Gesetze erfolgten Entwickelung von \(x\) übereinzustimmen. Vielmehr müssen, damit dies der Fall sei, \(a, a_1,\ldots , a_n, x_{n+1}\) gewisse Bedingungen erfüllen. Diese stellt der Verfasser zunächst auf. Sodann wird der Nachweis geführt, dass die Entwickelung jeder complexen Grösse convergirt, dass sie abbricht, resp. periodisch wird, wenn die Grösse eine complexe rationale Zahl ist, resp. einer quadratischen Gleichung mit ganzzahlig complexen Coefficienten genügt. Mit der untersuchten Kettenbruchentwickelung steht nun ferner eine andere in genauestem Zusammenhange, bei welcher an Stelle der Einteilung der complexen Zahlenebene in die oben genannten Quadrate eine solche in Gebiete tritt, die von Kreisstücken begrenzt sind. Für diese zweite Entwickelung werden die analogen Sätze wie für die erste bewiesen.”

“Der Verfasser glaubt, dass die von ihm genauer erforschte Art der Kettenbruchentwicklung als Grundlage für die Theorie der quadratischen Formen mit complexen Variablen und complexen Koeffizienten dienen könne” (Archive of Halle University, Rep. 21 Nr. 162).

See Hawkins (2008) for a very informative study of this topic.

See Mathews (1912, 329). The old-fashioned, direct translation chain fraction from the German Kettenbruch is outdated. The English notion continued fraction has been used since around 1900 the first articles on this topic in English had been published.

Perron’s (1913) monograph is not yet translated into English!

References

Arwin, A. 1926. Einige periodische Kettenbruchentwicklungen. Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik 155: 111–128.

Arwin, A. 1928. Weitere periodische Kettenbruchentwicklungen. Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik 159: 180–196.

Auric, M. 1902. Essai sur la théorie des fractions continues. Journal de Mathématiques Pures et Appliquées 8: 387–431.

Bachmann, G. 1872. Die Lehre von der Kreistheilung und ihre Beziehungen zur Zahlentheorie. Berlin: Teubner.

Bianchi, L. 1959. Opere. Vol. XI: Corrispondenza. Roma: Edizioni Cremonese (Italian).

Borel, E. 1903. Sur l’approximation des nombres par des nombres rationnels. C.R. Academy of Sciences, Paris 136: 1054–1055.

Bosma, W., and Gruenewald, D. 2012. Complex numbers with bounded partial quotients. J. Aust. Math. Soc. 93: 9–20.

Brezinski, C. 1991. History of continued fractions and Padé approximants. Berlin: Springer.

Burau, W. 1966. Der Hamburger Mathematiker Hermann Schubert. Miteilungen der Mathematischen Gesellschaft Hamburg 9: 10–19.

Burau, W., and B. Renschuch. 1993. Ergänzungen zur Biographie von Hermann Schubert. Miteilungen der Mathematischen Gesellschaft Hamburg 13: 63–65.

Cassels, J. 1957. An introduction to diophantine approximation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Courant, R., and A. Hurwitz. 1992. Vorlesungen über allgemeine Funktionentheorie und elliptische Funktionen. Berlin: Springer.

Décaillot, A.-M. 2011. Cantor und die Franzosen. Berlin: Springer.

Dickson, L. 1923. History of the theory of numbers, vol. III. Washington: Carnegie Inst.

Dickson, L. 1927. Algebren und ihre Zahlentheorie. Zürich & Leipzig.

Dieudonné, J., and J. Guérindon. 1985. Die Algebra seit 1840. In Geschichte der Mathematik, ed. J. Dieudonné. Berlin: Vieweg.

Dirichlet, P. 1842. Recherches sur les formes quadratiques á coëfficients et á indéterminées complexes. Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik 24: 291–371.

Dirichlet, P. 1879. Vorlesungen über Zahlentheorie, 3rd ed., ed. R. Dedekind. Braunschweig: Vieweg.

Dutka, J. 1982. Wallis’s product, Brouncker’s continued fraction, and Leibniz’s series. Archive for History of Exact Sciences 26: 115–126.

Dyson, F. 2009. Birds and frogs. Notices of the American Mathematical Society 56: 212–223.

Fölsing, A. 1993. Albert Einstein. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

Ford, L. 1918. Rational approximation to irrational complex numbers. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 19: 1–42.

Fowler, D. 1990. The mathematics of Plato’s academy: A new reconstruction. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Frei, G. 1985. Der Briefwechsel David Hilbert—Felix Klein (1886–1918), Arbeiten aus der Niedersächsischen Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen, ed. G. Frei. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Frei, G. 1995. Adolf Hurwitz (1859–1919). In Die Albertus-Universität zu Königsberg und ihre Professoren. Aus Anlass der Gründung der Albertus-Universität vor 450 Jahren, D. Rauschning, et al. (eds.), 527–541 Berlin: Duncker & Humblot. Jahrbuch der Albertus-Universität zu Königsberg.

Gintner, H. 1936. Ueber Kettenbruchentwicklung und über die Approximation von komplexen Zahlen. Dissertation, University of Vienna.

Hawkins, T. 2008. Continued fractions and the origins of the Perron–Frobenius theorem. Archive for History of Exact Sciences 62: 655–717.

Hensley, D. 2006. Continued fractions. Singapore: World Scientific.

Hermite, C. 1885. Sur la théorie des fractions continues. Darb Bulletin IX: 11–13.

Hilbert, D. 1921. Adolf Hurwitz. Mathematische Annalen 83: 161–172.

Hofreiter, N. 1938. Über die Kettenbruchentwicklung komplexer Zahlen und Anwendungen auf diophantische Approximationen. Monatshefte für Mathematik und Physik 46: 379–383.

Hurwitz, A. 1972. Die Mathematischen Tagebücher und der übrige handschriftliche Nachlass von Adolf Hurwitz. http://www.e-manuscripta.ch/.

Hurwitz, A. 1881. Grundlagen einer independenten Theorie der elliptischen Modulfunctionen und Theorie der Multiplicatorgleichungen erster Stufe. Diss. Leipzig, Klein Ann. XVIII: 528–592.

Hurwitz, A. 1888. Ueber die Entwickelung complexer Grössen in Kettenbrüche. Acta Mathematica XI: 187–200.

Hurwitz, A. 1889. Ueber eine besondere Art der Kettenbruch-Entwickelung reeller Grössen. Acta Mathematica XII: 367–405.

Hurwitz, A. 1894a. Review JFM 26.0235.01 of Hurwitz (1895) in jahrbuch über die fortschritte der mathematik. Available via Zentralblatt.

Hurwitz, A. 1894b. Ueber die angenäherte Darstellung der zahlen durch rationale Brüche. Mathematische Annalen XLIV: 417–436.

Hurwitz, A. 1894c. Ueber die Theorie der Ideale. Göttingen Nachrichten, 291–298.

Hurwitz, A. 1896. Ueber die Kettenbrüche, deren Teilnenner arithmetische Reihen bilden. Zürich. Naturf. Ges. 41(2): 34–64.

Hurwitz, A. 1919. Vorlesungen über die Zahlentheorie der Quaternionen. Berlin: Springer.

Hurwitz, A. 1932. Mathematische Werke. Bd. 1. Funktionentheorie; Bd. 2. Zahlentheorie, Algebra und Geometrie. Birkhäuser, Basel.

Hurwitz, A., and F. Rudio. 1894. Briefe von G. Eisenstein an M. A. Stern. Schlömilch Z XL(Suppl): 169–203.

Hurwitz, A., and H. Schubert. 1876. Ueber den Chasles’schen Satz \(\alpha \mu +\beta \nu \). Göttingen Nachrichten 503.

Hurwitz, J. 1895. Ueber eine besondere Art der Kettenbruch-Entwickelung complexer Grössen. Dissertation at the University of Halle.

Hurwitz, J. 1902. Über die Reduktion der binären quadratischen Formen mit komplexen Koeffizienten und Variabeln. Acta Mathematica 25: 231–290.

Hurwitz-Samuel, I. 1984. Erinnerungen an die Familie Hurwitz, mit Biographie ihres Gatten Adolph Hurwitz, Prof. f. höhere Mathematik an der ETH. Zürich: ETH library.

Ito, S., and S. Tanaka. 1981. On a family of continued-fraction transformations and their ergodic properties. Tokyo Journal of Mathematics 4: 153–175.

Jacobi, C. 1868. Allgemeine Theorie der kettenbruchähnlichen Algorithmen, in welchen jede Zahl aus drei vorhergehenden gebildet wird. Journal für die Reine und Angewandte Mathematik. 69: 29–64. [resp. Borchardt J. LXIX (1868), 29–64; communicated by E. Heine from the collected works of C.G. Jacobi].

Johnson, P. 1972. A history of set theory. Boston, MA: Prindle, Weber & Schmidt.

Kaneiwa, R., I. Shiokawa, and J.-I. Tamura. 1975. A proof of Perron’s theorem on diophantine approximation of complex numbers. Keio Engineering Reports 28: 131–147.

Kaneiwa, R., I. Shiokawa, and J.-I. Tamura. 1976. Some properties of complex continued fractions. Comment. Math. Univ. St. Pauli 25: 129–143.

Klein, F. 1908. Elementary mathematics from an advanced standpoint. New York: Dover.

Klein, F. 1926. Vorlesungen über die Entwicklung der Mathematik im 19. Jahrhundert Teil. 1. Berlin: Springer.

Koksma, J. 1936. Diophantische Approximationen. Berlin: Springer.

Krantz, S. 2005. Mathematical Apocrypha Redux. Washington, DC: Mathematical Association of America.

Lagrange, J. 1770. Additions au mémoire sur la résolution des équations numéiques. Mém. Acad. royale sc. et belles-lettres Berlin 24: 111–180.

Lehto, O. 1998. Mathematics without borders. Berlin: Springer.

Lorentzen, L., and H. Waadeland. 1992. Continued fractions with applications. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Lunz, P. 1937. Kettenbrüche, deren Teilnenner dem Ring der Zahlen 1 und \(\sqrt{-2}\) angehören. Diss. München, A. Ebner München.

Mathews, G. 1912. A theory of binary quadratic arithmetical forms with complex integral coefficients. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society 11: 329–350.

Michelangeli, N. 1887. On some properties of continued fractions with complex partial quotients (in Italian). Napoli: A. Bellisario e C.

Minnigerode, C. 1873. Ueber eine neue Methode, die Pell’sche Gleichung aufzulösen. Göttingen Nachrichten 619–652.

Nakada, H. 1981. Metrical theory for a class of continued fractions transformations. Tokyo Journal of Mathematics 4: 399–426.

Perron, O. 1907. Grundlagen für eine Theorie des Jacobischen Kettenbruchalgorithmus, habilitation thesis. Mathematische Annalen 64: 1–76.

Perron, O. 1932. Quadratische Zahlkörper mit Euklidischem Algorithmus. Mathematische Annalen 107: 489–495.

Perron, O. (1st ed. 1913; 2nd ed. 1929; 3rd ed. 1954. in two volumes). Die Lehre von den Kettenbrüchen. Leipzig: Teubner.

Pólya, G. 1987. The Polya picture album: Encounters of a mathematician, ed. G.L. Alexanderson. Boston: Birkhäuser.

Pringsheim, A. 1900. Ueber die Convergenz periodischer Kettenbrüche. Münch. Ber. 463–488.

Rüdenberg, L. and H. Zassenhaus. 1973. Hermann Minkowski Briefe an David Hilbert. Berlin: Springer.

Rasche, A. 2011. Hurwitz in Hildesheim. Bachelor thesis, University of Hildesheim.

Roberts, S. 1884. Note on the Pellian equation. Proceedings of London Mathematicial Society XV: 247–268.

Rowe, D. 1986. “Jewish Mathematics” at Göttingen in the Era of Felix Klein. Isis 77: 422–449.

Rowe, D. 2007. Felix Klein, Adolf Hurwitz, and the “Jewish question” in German academia. The Mathematical Intelligencer 29: 18–30.

Schmidt, A. 1975. Diophantine approximation of complex numbers. Acta Mathematica 134: 1–85.

Schmidt, A. 1982. Ergodic theory for complex continued fractions. Monatshefte für Mathematik 93: 39–62.

Schubert, H. 1879. Kalkül der abzählenden Geometrie. Leipzig: Teubner.

Schubert, H. 1902. Niedere analysis, 1. Teil. Leipzig: Göschensche Verlagshaus.

Schweiger, F. 1982. Continued fractions with odd and even partial quotients. Mathematisches Institut der Universitat Salzburg, Arbeitsber 4/82: 45–50.

Seidel, L. 1846/47. Untersuchungen über die Konvergenz und Divergenz der Kettenbrüche. Habilitation thesis, Munich.

Shiokawa, I. 1976. Some ergodic properties of a complex continued fraction algorithm. Keio Engineering Reports 29: 73–86.

Stedall, J. 2000. Catching Proteus: The collaborations of Wallis and Brouncker. I: Squaring the circle. II: Number problems. Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 54: 293–316, 317–331.

Stein, A. 1927. Die Gewinnung der Einheiten in gewissen relativ-quadratischen Zahlkörpern durch das. J. Hurwitzsche Kettenbruchverfahren. Journal für die Reine und Angewandte Mathematik 156: 69–92.

Stern, M. 1829. Observationes in fractiones continuas. Dissertation, Göttingen.

Stern, M. 1848. Über die Kennzeichen der Convergenz eines Kettenbruchs. Journal für die Reine und Angewandte Mathematik 37: 255–272.

Stern, M. 1860. Lehrbuch der Algebraischen Analysis. Leipzig und Heidelberg: C.F. Winter’sche Verlagshandlung.

Stolz, O. 1885. Vorlesungen über allgemeine Arithmetik. Nach den neueren Ansichten bearbeitet. Zweiter Teil: Arithmetik der complexen Zahlen mit geometrischen Anwendungen. Leipzig: Teubner.

Tanaka, A. 1985. A complex continued fraction transformation and its ergodic properties. Tokyo Journal of Mathematics 8: 191–214.

Vivanti, G. 2005. Review JFM 19.0197.03 of Michelangeli (1887) in Jahrbuch über die Fortschritte der Mathematik. Available via Zentralblatt.

W.H.Y. 1922. Adolf Hurwitz, obituary note. Proceedings of London Mathematical Society 2: 48–54.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Ms. Annika Rasche and Prof. Jürgen Sander from the University of Hildesheim. In particular, the Bachelor thesis of Ms. Rasche (2011) on life and work of Adolf Hurwitz had been a big help and a guide at the beginning of our studies. Furthermore, the authors would like to thank Prof. Thomas Baier from Würzburg University for translating Julius’ vita from Latin, the first named author’s parents for helping with the old German handwriting, Prof. Dr. Christoph Baxa from the University of Vienna for his help with Gintner (1936) as well as professors Fritz Schweiger and Iekata Shiokawa for submitting their works. Our very special thanks go to Prof. Klaus Volkert and Prof. Jeremy J. Gray for their help and support for writing this article on the history of mathematics. Last not least, the authors are very grateful for the kind support from the archives at Basel, Halle, and Zurich. The photographs of Julius and Adolf Hurwitz are taken from Riesz’s register in Acta Mathematica from 1913; the photographs of the documents on these pages are taken with the permission of the archives at Halle and Zurich. All translations from German to English have been made by the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by: Jeremy Gray.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oswald, N.M.R., Steuding, J.J. Complex continued fractions: early work of the brothers Adolf and Julius Hurwitz. Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 68, 499–528 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00407-014-0135-7

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00407-014-0135-7