Abstract

This paper discusses the application of qualitative scenarios to understand community vulnerability and adaptation responses, based on a case study in the Slave River Delta region of the Northwest Territories, Canada. Three qualitative, graphic scenarios of possible alternative futures were developed, focusing on two main drivers: climate change and resource development. These were used as a focal point for discussions with a cross-section of residents from the community during focus groups, interviews and a community workshop. Significant overlap among the areas of perceived vulnerability is evident among scenarios, particularly in relation to traditional land use. However, each scenario also offers insights about specific challenges facing community members. Climate change was perceived to engender mostly negative livelihood impacts, whereas resource development was expected to trigger a mix of positive and negative impacts, both of which may be more dramatic than in the “climate change only” scenario. The scenarios were also used to identify adaptation options specific to individual drivers of change, as well as more universally applicable options. Identified adaptation options were generally aligned with five sectors—environment and natural resources, economy, community management and development, infrastructure and services, and information and training—which effectively offer a first step towards prioritization of “no regrets” measures. From an empirical perspective, while the scenarios highlighted the need for bottom-up measures, they also elucidated discussion about local agency in adaptation and enabled the examination of multi-dimensional impacts on different community sub-groups. An incongruity emerged between the suite of technically oriented adaptation options and more socially and behaviourally oriented barriers to implementation. Methodologically, the qualitative scenarios were flexible, socially inclusive and consistent with the Indigenous worldview; allowed the incorporation of different knowledge systems; addressed future community vulnerability and adaptation; and led to the identification of socially feasible and bottom-up adaptation outcomes. Despite some caveats regarding resource requirements for participatory scenario development, qualitative scenarios offer a versatile tool to address a range of vulnerability and adaptation issues in the context of other Indigenous communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rapid changes in socioeconomic and environmental conditions are being experienced across the Circumpolar North, including unprecedented climate change (ACIA 2005; IPCC 2007a, b; Lemmen et al. 2008). The need to understand implications for human systems in the North has stimulated a range of human dimensions research, with particular emphasis on Indigenous Peoples. In the Canadian North, this has led to a significant focus on vulnerability and adaptation research in Inuit regions (Ford et al. 2012; Nickels et al. 2006; Pearce et al. 2010), although examples from sub-Arctic First Nations communities do exist (Ogden and Innes 2007; Wesche and Armitage 2010a; Wesche et al. 2011).

Indigenous Peoples have a unique and profound relationship with the land based on multi-generational, place-based engagement with the natural world (Cajete 2000). Indigenous knowledge systems differ from Western knowledge systems and are founded on the development and sharing of oral histories and experiential, place-based learning. Storytelling is an important mechanism for eliciting holistic perspectives and participating in knowledge translation (Dell et al. 2011).

While the content, depth and level of detail of Indigenous knowledge vary among individuals (Laidler 2006), Indigenous experts are known to identify and monitor a range of environmental indicators. These include changing seasonal conditions, catch per unit effort, wildlife distribution patterns and abundance, biophysical extremes or deviations from environmental norms, wildlife health through body condition, and changes in environmental quality through animal characteristics and behaviour (Berkes et al. 2007). Indigenous knowledge thus offers important contributions that are complementary to Western scientific knowledge for documenting and understanding climate change and its impacts, in combination with other stressors (Gearheard et al. 2006; Krupnik and Jolly 2002; Laidler 2006; Riewe and Oakes 2006).

Syntheses of human dimensions of climate change research in the Canadian Arctic indicate gaps in a) the projection of future vulnerability and adaptation, and b) potential interaction between environmental changes and human systems, including the effect of socioeconomic and socio-demographic characteristics on community experiences of change. Addressing these gaps requires local-scale, place-based research (Ford et al. 2012; Pearce et al. 2010). To date, climate change adaptations in northern communities have largely been short term, ad hoc and reactive (Ford et al. 2012), perhaps reflecting the tendency of Indigenous societies to deal with the present and respond to situations as they arise, rather than trying to predict and plan for the future (Bates 2007). However, research shows that adaptation would be more effective if it were anticipatory and policy-oriented. Thus, methods that are consistent with Indigenous ways of learning and sharing knowledge are needed.

Participatory approaches are required to understand vulnerability and adaptation options from the perspective of those affected by social-ecological change. They can help bridge different types of knowledge to enhance understanding about regional change and its implications (Gearheard et al. 2006; Laidler 2006; Pearce et al. 2009), and shift the focus towards problem-oriented and reflexive processes (Armitage et al. 2011; Raymond et al. 2010; Reed et al. 2013). Ford et al. (2010a) point to rich case studies and analogue methodologies (temporal and spatial) as useful ways to characterize sensitivity to climatic risks (e.g. who, what and why?), determinants of adaptive capacity and opportunities for adaptation. Hovelsrud and Smit (2010) emphasize the importance of bottom-up or “starting point” strategies to vulnerability assessment that privilege stakeholder perspectives in identifying sensitivities to changes in system conditions and the processes by which vulnerabilities may be reduced. This is particularly important as the subjective dimensions of vulnerability and adaptive capacity are better theorized and empirically documented (see O’Brien and Wolf 2010).

The importance of involving stakeholders and decision-makers in policy-oriented vulnerability and adaptation research is well recognized (Ayers and Forsyth 2009; Carter et al. 2007; Dodman and Mitlin 2013; Ford et al. 2010b; Pearce et al. 2009; Sheppard et al. 2011; Wesche and Armitage 2010a; Wolfe et al. 2007). If expectations are clear and participation is effectively scoped, engaging and empowering individuals and communities can improve stakeholder understanding and buy-in to both the process and resulting outcomes (Few et al. 2007; Sheppard et al. 2011). Furthermore, incorporating local experience and knowledge fosters the development of adaptation strategies in the context of local conditions that may not be clearly evident to, or understood by, outsiders and may result in lower-cost, socially oriented solutions (Ayers and Forsyth 2009; Dodman and Mitlin 2013). As such, local involvement can enhance stakeholder understanding of the issues and the effectiveness of decision-making processes (Waltner-Toews et al. 2003). Qualitative scenarios employed as part of a participatory research process provide one effective way to enhance this engagement.

Scenario planning, initially a tool developed for the military, has been adapted for corporate management and more recently for assessing and planning for multiple aspects of environmental change (Bohensky et al. 2011, 2006; Gidley et al. 2009; Kok et al. 2007; Miller and Waller 2003; Odada et al. 2009; Peterson et al. 2003; Peterson 2007; Sheppard et al. 2011). In these contexts, scenarios are not meant to be probabilistic forecasts of future conditions, but are rather images of possible alternate futures based on assumptions about key relationships and drivers of change (Chaudhury et al. 2013; Nakićenović 2000; Peterson et al. 2003b). Scenarios are particularly useful where uncertainty is high and where it is impractical or impossible to test system responses through manipulation (Peterson et al. 2003a, b; Polasky et al. 2011).

Qualitative scenarios have been shown to offer a useful method for engaging stakeholders in anticipatory adaptation planning in a way that translates climate change trends to the local scale and makes them relevant to local people. They have been used in a range of settings, with demonstrated utility in improving adaptive co-management of natural resources, stimulating social learning (Gidley et al. 2009; Wollenberg et al. 2000) and incorporating different epistemologies (Bennett and Zurek 2006). To date, however, their use with Indigenous communities and the explicit incorporation of Indigenous knowledge has been limited.

This paper outlines the empirical and methodological utility of qualitative scenarios to understand community vulnerability and adaptation responses in the Slave River Delta region of the Northwest Territories, Canada. Here, the development and use of qualitative scenarios provided a novel mechanism through which to: (1) incorporate information from both Indigenous and Western knowledge about environmental change (sensu Huntington 2000) to help generate a holistic understanding; (2) increase the relevance of formal scientific projections for community members by capturing that information in an accessible format consistent with Indigenous narrative traditions; and (3) understand community vulnerability to future environmental change and identify relevant adaptation options through a socially inclusive process (sensu Few et al. 2007; Sheppard et al. 2011).

We first provide an overview of the context for this research, including the ecological, socioeconomic and institutional setting associated with the Slave River Delta region. Next, we describe the process of qualitative scenario development and application. Key findings are then highlighted with reference to vulnerability and adaptation to two major drivers of change, namely climate change and resource development. We conclude with reflections on the empirical and policy contributions derived from the use of the qualitative scenarios, as well as the methodological utility of these scenarios for participatory environmental change research and adaptation policy.

Research setting

Northern regions, including the Arctic and sub-Arctic, are climate change hotspots (ACIA 2005) and are particularly susceptible to resulting impacts due to ecosystem fragility (Bone 2009). Both ecosystem services and human well-being in the North are being affected, prompting increased focus on adaptation planning (ACIA 2005; AHDR 2004; Anisimov et al. 2007; Chapin III et al. 2005; Furgal and Prowse 2008; IPCC 2007a; WWF 2008). While northern Indigenous societies have adapted for millennia, the combined impact of rapid environmental change and globalization-induced economic development are testing the limits of this capacity (ACIA 2005; O’Brien and Leichenko 2000).

In Canada, rural resource-dependent communities, including Indigenous communities that rely on a subsistence economy, are often particularly vulnerable. This is due in part to the elevated sensitivity to climate change of land- and natural resource-based activities and to the presence of elements that constrain adaptation, such as limited economic diversification, lack of resources for adaptation planning and restricted access to services (Warren and Egginton 2008).

The settlement of Fort Resolution, NWT (61º10′N, 113º41′W), is one such community. It is located on the south shore of Great Slave Lake, accessible by all-season road from Hay River. More than 87 % of the ~500 residents are Indigenous Dene (First Nations) or Métis (Northwest Territories Bureau of Statistics 2007), the majority of which have inter-generational ties to the surrounding traditional land use area. Located 10 km east of the settlement, the Slave River Delta (SRD) is the central ecological support system for the community, characterized by periodic flood events, numerous vegetation and habitat types, and significant biological diversity. It provides critical habitat for migrating waterfowl (IBA Canada 2011), fish, muskrat (English 1984) and other wildlife, such as moose, beaver, lynx, mink and marten.

Like other large freshwater deltas in Northern Canada, the SRD is naturally changing and evolving. It is also highly sensitive to climate change and human-induced changes such as upstream impoundment (Prowse et al. 2006, 2002) and consumptive water use (Brock et al. 2010), which influence ecosystem dynamics and, by extension, local land and resource use. The delta’s habitat diversity and wildlife resources are of central importance to the subsistence livelihood strategies and socio-cultural integrity of community members in Fort Resolution, who use the area for hunting, trapping, fishing, transport and recreation (Hoare 1995). For residents, ongoing socio-cultural changes also influence land and resource use patterns and the ability to adapt to change. As in other northern contexts (e.g. Duerden 2004), lifestyles have become more sedentary, globalization pressures have increased, Western education systems have become the norm, demographics have shifted, and traditional land-based activities have decreased, all virtually within a generation. Regardless of these changes, resource harvesting activities remain important to social and cultural systems in Fort Resolution.

The political climate is also in flux. Both the Akaitcho Dene First Nations and the Northwest Territory Métis Nation are currently negotiating land, resources and self-government agreements with the Government of Canada and the Government of the Northwest Territories. While Indigenous rights relating to land and resources are slowly being clarified, pressures from climate change and resource development continue to increase. As such, evolving governance structures offer important opportunities to incorporate adaptive measures into the environmental planning process (Wesche and Armitage 2010b).

Methods

To explore a range of potential future environmental changes and impacts on the SRD region, we developed a series of qualitative scenarios of possible alternative futures and tested their utility in an Indigenous setting to evaluate whether their story-oriented nature helped to enable a discussion of anticipatory planning. Each culturally grounded scenario incorporated both an oral narrative and a representative illustration, reflecting the tradition of sharing and learning through oral histories, the evolving nature of place-based narratives and the commonly practiced process of learning by observation that is fundamental to Indigenous cultures (Berkes 2012). Such scenarios are “plausible example(s) of what could happen under particular assumptions and conditions … [and are] contrasted against one another to provide a tool for thinking about the relationships between choices, dynamics, and alternative futures” (Peterson et al. 2003a: 2).

The scenario process described here evolved as part of a long-term collaborative research project on environmental change in the SRD region. During an earlier phase, the lead author spent several months in the field conducting semi-structured interviews with 33 Indigenous knowledge holders as well as 19 decision-makers at local and regional levels to document and understand community vulnerability to environmental change. This, combined with intensive participant observation, provided a substantive contextual background and clearly identified the two primary drivers of environmental change—climate change and resource development—and their relationship with social and environmental variables (Wesche and Armitage 2010a, b; Wesche 2009; Wolfe et al. 2007). To build on this understanding, consultation with local leaders led to the selection of scenarios as a useful tool for exploring future vulnerability and identifying adaptation options in a policy-relevant manner. While initial plans involved engaging stakeholders in the scenario-building process, this was ultimately precluded by logistical constraints. Funding constraints and competing commitments on the researcher side, combined with time constraints for community participants (e.g. due to employment, family and other commitments), imposed severe limitations. Thus, an alternate approach was chosen, where the authors used collected data combined with scientific information to create several plausible scenarios, aided by periodic consultation with a small group of community leaders (e.g. the Environmental Manager, the Interim Measures Agreement Coordinator and the Lands Negotiator).

Four elements are common to the majority of scenario analyses: defined purpose, understanding of system structure and drivers of change, scenario creation, and applicability for decision-makers (Wollenberg et al. 2000). The first two elements were achieved through the earlier research phase, and scenario creation focused on the key drivers of change. To move beyond the focus on average temperature and precipitation conditions espoused in many climate change impact scenarios (Smit and Skinner 2002), a broad range of possible exposures was incorporated.

Drawing in large part on descriptions of past and current trends elucidated during community interviews, the climate change components also incorporated projections determined through a synthesis of existing research on climate change impacts, trends and projections in the North. A summary of past (1950-present) and anticipated future (2050 and 2100) climate change-related trends was collated from studies focused on Arctic and/or sub-Arctic regions and more specifically on the Mackenzie Basin and/or SRD region. Primary themes included climate, land and animals, water resources, permafrost, forestry, fisheries and aquatic systems, transportation, and human health and well-being (ACIA 2005; Cohen 1997a, b; Couture et al. 2000; Environment Canada 2004; Health Canada 2002; Lemmen and Warren 2004; Rouse et al. 1997; State of the Canadian Cryosphere 2005).

The resource development components were extrapolated from community member descriptions of past trends during the 1964 to 1988 period when the Pine Point lead and zinc mine was in operation 60 km west of Fort Resolution (Wesche 2009), narrative accounts from other communities, and literature on northern resource boom towns and their impact on Indigenous communities (Bone 2009; Keeling and Sandlos 2009; Kendall 1992) in the context of evolving relationships and negotiated agreements between Indigenous groups and mining companies (Faircheallaigh 2010; Fidler 2009).

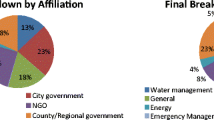

Initially, four alternate storylines were developed to cover the variability among possible futures, while the even number reduced the perception of a “most likely” or “central” case (Nakićenović 2000) (Table 1). The “Small Town” scenario illustrated limited change in both climate and resource development. “Shifting Seasons” combined elevated climate change projections with limited resource development, while “Boom Town” illustrated the opposite scenario: limited climate change paired with significant resource development. The “Akaitcho Mines” scenario incorporated significant change on both climate and development fronts. The year 2030 was used as a timeframe that was relevant for current residents, and one within which significant changes are likely. An image was developed for each scenario, including a series of symbols depicting both environmental and socioeconomic variables (Fig. 1).Footnote 1 The descriptive title and a narrative storyline was paired with each image, and simplified bullet points of prevailing trends were created for use in the focus groups (Table 2).

The scenarios were used as tools to build shared understandings of community vulnerability to future change and identify applicable adaptation options for decision-makers. They provided a focal point for discussions with a cross-section of residents from the community via five focus groups (N = 20), semi-structured interviews with local officials (N = 3) and a culminating adaptation workshop with local decision-makers (N = 11). For each scenario, participants were led through a structured discussion of key implications for local livelihoods (e.g. environmental impacts, social impacts, traditional activities, economy, health and well-being), opportunities for and barriers to adaptation (e.g. governance, resources, leadership, community cohesion), and the roles and responsibilities of various actors in planning for change. The focus of our scenario process was to engage stakeholders in identifying a range of vulnerabilities to which they may be exposed in different sectors, and anticipatory adaptation options to reduce vulnerability. While other applications have focused on stakeholder participation during scenario creation, our “actor-oriented” scenario process emphasized the learning processes that emerged from group interaction (see Chaudhury et al. 2013) around outcomes for decision-makers.

Results

The scenarios were designed so that participants could focus on each driver of change in turn—climate and resource development—and pinpoint specific vulnerabilities in relation to them. In this regard, we define vulnerability as “the manner and degree to which a community is susceptible to conditions that directly or indirectly affect [its] wellbeing or sustainability” and recognize that it is a function of exposure-sensitivity and adaptive capacity (Hovelsrud and Smit 2010: 5). In this context, exposure-sensitivity refers to the likelihood and level of exposure of a community to a stress or stimulus, and its susceptibility to that exposure. Communities often have significant ability to cope with or respond to such stresses, termed adaptive capacity (Hovelsrud and Smit 2010). With reference to vulnerability, the “Small Town” scenario depicts a continuation of “business as usual” and acts as a baseline scenario against which the other two scenarios—which depict more dramatic change—can be contrasted. Participants deemed the scenarios to be plausible—and in some cases likely—and also noted their utility in stimulating discussion around planning for the future (i.e. what can be done, rather than focusing solely on the barriers).

Exposure-sensitivities

Participants most often discussed vulnerability in relation to their own livelihood activities and well-being, both of which are linked to perceived environmental conditions. For example, they described how environmental changes are likely to influence individual and collective capabilities, material and social assets, and activities required for a healthy and happy life in the community. Different aspects of livelihood vulnerability were articulated under each scenario, as well as the potential for both positive and negative impacts (Table 3).

Potential changes to the environmental system and quality of natural resources (e.g. disruption of animal populations and migration patterns, decreased access for land users, increased risk of weather extremes, and water and food contamination) were identified as key exposure-sensitivities. These factors were often linked to human health concerns. For example, a number of participants highlighted the effects of climate change on fish and animal health (e.g. more parasites), requiring increased education and vigilance regarding food choices. Contaminated water and traditional food sources were cited as two key factors that would likely push people to move away from the community.

The “Shifting Seasons” scenario was perceived to cause mostly negative impacts on local livelihoods, with the intensity of vulnerability being directly correlated with the rate and level of climate variability and change. Progressive climatic changes would continue to impact the access to, availability of, and quality of traditional foods, eliciting concerns about food security and travel safety on the land. For example, one focus group highlighted feedbacks that linked warmer temperatures with increasingly uncertain ice conditions, thus limiting hunting; consequently, increased income would be required for purchasing meat and other store-bought foods. Other participants were concerned about the safety of land users who are not prepared for changes to ice and weather conditions, as they may fall through the ice or suffer frostbite.

In contrast, “Boom Town” evoked a distinct mix of potentially more pronounced positive and negative impacts. A number of participants noted their personal resistance to resource extraction, indicating that digging up the earth for marketable resources contravenes their cultural beliefs and that diverting people from traditional land use practices hinders the continued evolution and transmission of Indigenous knowledge. Others highlighted the positive aspects of this scenario, including job creation, training opportunities and economic growth. While a significant number of participants supported the idea of resource development, they emphasized the need for community planning, preparedness and risk mitigation.

Climate change was seen as an entirely external force that participants were unable to influence; thus, they were resigned to its outcomes. “We need increased awareness within the community; all we can do is watch and learn” (Workshop participant). In contrast, participants perceived that they have some degree of choice and control over if, when and how resource development projects are implemented within their traditional territory. “There’s a clear role for local government in negotiating these agreements and in arranging training, etcetera, to ensure that local residents are able to take advantage of work opportunities” (Focus Group 1 Participant).

Participants noted that the continuity of traditional land use and cultural practices would be challenged under all scenarios. Harvesters would suffer the most negative impacts, both economic and personal, as harvesting is deemed essential to their livelihoods as well as to their vibrancy and well-being. Individuals would be less likely to harvest pelts or hunt if they cannot cover their travel costs (either via pelt sales or waged employment) or if they are concerned about travel safety. At the same time, the well-being of community residents who rely on traditional food provided by family and friends would also be indirectly affected by changing availability and access. Participants indicated that specific community sub-groups (e.g. residents who had more recently moved to the community from a nearby outpost, traditional land users and single mothers on welfare) would likely be further marginalized when faced with changing conditions; this is particularly true for those who are poor, supplement their diet and income with traditional food, have limited training, or experience barriers to employment and resource access.

A key concern was that elders, key community members identified as repositories of knowledge and values, are not able to adapt their ways of living as quickly as younger people who have a broader cross-cultural knowledge base. “Boom Town” was deemed particularly challenging for both elders and land users who would experience mental, emotional and spiritual consequences. By contrast, the youth were perceived as the most likely to engage with and benefit (in non-traditional ways) from such a scenario due to their adaptability and pre-existing exposure to Western culture. A “Shifting Seasons” scenario would provide little for youth to thrive on, especially since many lack the necessary skills and knowledge for land use and survival, whereas elders were seen to be somewhat better prepared for climate-related changes.

Adaptation strategies and adaptive capacity

A range of adaptation options were discussed, some being specific to individual drivers of change, while others are more universally applicable. Commonly cited options respond to impacts in five sectors: environment and natural resources, economy, community management and development, infrastructure and services, and information and training (Table 4). This list effectively offers a first step towards prioritization.

Existing and suggested adaptation strategies in response to climate change-related pressures focused on adjusting land use activities (e.g. waiting out unfavourable conditions, diversifying livelihoods through alternate employment), engaging in environmental planning and monitoring (e.g. integrated land use planning, community emergency planning, water and air quality monitoring), and reconnecting with culture (e.g. culture camps, community hunts). By contrast, improving both local education and training opportunities in all areas (e.g. technical training for environmental monitoring, employment in the resource development or service industry) and enhancing political leadership (e.g. leadership training, establishing a consortium of local and regional organizations, education and awareness-building about environmental change) were highlighted as necessary for adapting to and benefiting from resource development in the region. This reflects the perception that climate change has more serious impacts on the broader biophysical environmental system, cultural connection to the land and place-based identity, while resource development may result in more prevalent social impacts as well as local environmental challenges. The emphasis placed on economic ventures, development of infrastructure and services, and social and health-related strategies was more comparable between scenarios.

Despite the range of suggested adaptation strategies, participants generally felt that the community is currently underprepared on a variety of levels to deal effectively with rapid environmental change. Barriers were identified in relation to socio-cultural norms (e.g. inter-group tensions, diverse beliefs regarding the applicability of different types of knowledge, attitudes regarding voluntary engagement), local capacity (e.g. limited qualified personnel; rapid employee turnover; limited scope for stable, representative leadership), material resources (e.g. limited long-term funding, high management costs, inadequate infrastructure) and regulations (e.g. constraints on land ownership, long-term planning limitations due to governance structure). These challenges are diverse, and overcoming them requires multiple congruent and lasting efforts to strengthen different elements of the community’s adaptive capacity. Furthermore, these efforts must be cross-scale in nature, as local barriers are compounded by challenges at higher levels of organization.

Discussion

Application of the qualitative scenario process in Fort Resolution revealed a number of valuable empirical, policy and methodological insights and contributed to community thinking about adaptation in several important ways. We discuss these contributions below.

Empirical and policy insights

Local actors provided significant empirical insights on exposure-sensitivities and adaptive capacity. The scenarios were useful in highlighting perceived levels of local control—or agency—over these drivers, in having participants think through or reveal connections among exposure-sensitivities, and in revealing how the impacts of change under contrasting scenarios may be experienced at different intensities by different social and demographic sub-groups. A comparison of impacts of the contrasting scenarios highlights the key role of knowledge systems (e.g. Indigenous versus Western) in determining the level of exposure-sensitivity of particular sub-groups to different scenarios of change.

Results of this process indicate how both individual and community vulnerability and the potential for implementation of adaptation measures are dependent on current local conditions, which are influenced by historical processes (see Brooks et al. 2005). Adaptation responses clearly require bottom-up action driven by local actors. Several informants reinforced the necessity of “doing it ourselves” to build successful solutions from within the community, rather than having processes imposed from the outside. At the same time, the mere articulation of pathways and interactions by local actors will not necessarily lead to the implementation of climate or development-sensitive adaptation options (e.g. legal, political, environmental). An understanding of cross-scale feedbacks and the role of non-local drivers of change as either constraints or enablers (Keskitalo and Kulyasova 2009) are crucial for determining an effective range of adaptation measures (Berkes et al. 2005).

The scenarios highlighted an interesting dichotomy. While the majority of adaptation strategies identified by participants appeared to be technical in nature, a significant number of the associated barriers to implementation related to social, cultural, behavioural or cognitive dimensions. In small, relatively remote, tight-knit Indigenous communities like Fort Resolution, implementing many of these strategies relies on functional social relationships both within local governance organizations and between the leadership and the residents they represent. For example, kinship and family ties play a crucial role in shaping the composition of local government and decision-making. It is fairly straightforward to plan and carry out a one-time event such as a community workshop or culture camp, whereas programmes like environmental monitoring, community planning or cultural development require a much higher and more sustained level of input and support. Furthermore, the successful implementation of long-term endeavours may require targeted local capacity-building and/or linkages with external resources (e.g. the development of research partnerships). It is clear that while technical fixes play an important role, effective adaptation requires much more than simple injections of funds or resources. It hinges on the willingness and ability of actors at different levels to engage in the effort with some level of collectivity and commitment. This is a key challenge in Fort Resolution where efforts by the various local organizations may lack alignment.

Methodological insights

Application of the scenario process revealed key insights and contributions relating to: (a) social inclusion in adaptation planning with an Indigenous community; (b) the value of scenarios in helping to integrate and weave together different types and sources of knowledge; (c) the role of scenarios in thinking through future vulnerability and adaptation, which has not been well considered in the literature; and (d) the importance of taking a cautious approach in engaging in scenario processes with Indigenous groups, given high transaction costs. These are outlined in Table 5 and discussed below.

First, the scenarios were socially inclusive, enabling a broad range of participants to engage and reflect on difficult issues confronting the community. The flexible method of application allowed people of all ages, backgrounds and levels of education to contribute to a policy-relevant process (e.g. an additional workshop was conducted with youth at the school). One participant commented on the utility of the images, indicating that he was able to fully participate in the discussion despite his inability to read the written material.

Second, qualitative scenarios may be particularly useful in Indigenous contexts. Two community leaders described the scenarios as “living, breathing models”, consistent with the holistic Indigenous worldview. Since the scenarios are symbolic representations and not predictive (or prescriptive), the discussions they generate become stories that change and evolve, much like oral history that is passed down from one generation to the next. This method offers an opportunity to bridge both Indigenous and Western knowledge understandings of change and to contribute to culturally appropriate adaptation frameworks that take into account the complexity of social–ecological interactions in the local context. Scenario-building using local knowledge is also a relatively inexpensive approach that enables the downscaling of outputs from regional-scale assessments into more easily accessible formats (Odada et al. 2009).

Third, the adaptation strategies outlined by participants reflect a list of desired outcomes. While not having been evaluated for economic cost, their social feasibility should be relatively sound given the participatory process. They provide an initial step towards the prioritization of actions based on community needs and interests to improve local-level adaptation. Methodologically, the qualitative scenarios help to frame the discussion about resource development and climate uncertainty in the context of community values and priorities, which is important for mainstreaming adaptation in marginalized communities (Boyle and Dowlatabadi 2011).

Fourth, while local-scale scenario development offers a promising method, some limitations presented themselves in this context. Participants were more likely to identify local-level forces and direct effects of change on livelihood dimensions, whereas external forces and indirect impacts were likely underestimated. Enfors et al. (2008) suggest that this may emerge with participants who have limited formal education and experience beyond the local scale, and who may not be accustomed to hypothetical approaches. It may also be, in part, a consequence of the types of representative symbols that were presented in the scenario graphics, as it is difficult to represent more abstract concepts like social dynamics or economic relationships. Increased participation of local people in the actual scenario development process would help to counter this problem and create more realistic scenarios, although this requires significant investment of researcher time and resources, and high levels of community collaboration during the fieldwork phase. In this case, despite a long-term relationship with the community (see Wolfe et al. 2007), efforts to engage community members in early design phases of the process met with challenges. The high transaction costs associated with participatory scenario development offer a cautionary tale for researchers interested in this approach. Constraints may be further amplified in small Indigenous communities where human—and other—resources are often overextended. Thus, our altered approach, which was integrated within a broader collaborative process and focused on the applicability for decision-makers, offers a useful alternative for other small Indigenous communities. Additionally, it allows for the inclusion of regional-level decision-makers in multi-scale processes (Kok et al. 2007), which improves opportunities for scaling up results.

Conclusion

Qualitative scenarios of the type outlined here, when embedded in a collaborative research process, offer a useful methodology for understanding future vulnerability from the perspective of local actors. When developed based on information gathered from literature reviews, existing data sets (e.g. downscaled climate data) and preliminary interviews, they allow for an evolving understanding of vulnerability to emerge over a series of field visits. The targeted nature of the scenarios can help to focus the discussion around tangible policy outcomes, which may be more difficult to achieve via semi-structured interviews or regular focus groups. Furthermore, they enable local actors with diverse knowledge and opinions regarding environmental change and its implications (Buys et al. 2012) to contribute to a collective process with shared outcomes.

Few strategies have been institutionalized in Indigenous communities to systematically think through the meaning of adaptation or the options available to build adaptive capacity. The qualitative scenario process described here provided such an opportunity. Although each of the presented options provides differential benefits depending on the type of future conditions that emerge, their broad applicability makes them key candidates for pinpointing “win–win” or “no regrets” measures (Ford et al. 2007; Handmer 2003).

As Indigenous Peoples increasingly engage in new forms of multi-level governance as an outcome of land rights processes and global changes, environmental governance is shifting towards more “bottom-up” approaches that favour local participation and decision-making. Such forms of governance provide key opportunities for incorporating multiple types of knowledge—including Indigenous knowledge—to improve management outcomes. Qualitative scenarios such as those described here offer an opportunity for knowledge co-production to address specific issues at the local scale within a broader, systems-oriented context (Armitage et al. 2011). As a tool for convergence of Indigenous and Western knowledge, qualitative scenarios have the potential to increase stakeholder participation and a focus on intercultural purpose during decision-making processes, and ultimately improve Indigenous control over environmental governance processes, all of which are linked to social, economic and environmental sustainability (Hill et al. 2012).

As used in this context, the qualitative scenarios were versatile, efficient and effective, consistent with Indigenous epistemologies, allowed the incorporation of different knowledge systems, and led to socially feasible and bottom-up adaptation outcomes. At the same time, limitations regarding resource requirements for participatory scenario development must be addressed. Qualitative scenario methodology can be further refined through future research with other Indigenous communities experiencing rapid change due to multiple stressors, both within and beyond Canada’s North.

Notes

During the first focus group, it became evident that the combination of factors in the “Akaitcho Mines” scenario made the outcome difficult to conceptualize, and participants felt that the exploration of vulnerabilities was repetitive. To reduce redundancy, the process was streamlined by eliminating the fourth scenario, thus focusing the discussion around vulnerabilities and adaptive strategies for each of the two major drivers of change in turn. As such, reference to the fourth scenario is absent from subsequent discussions, figures and tables.

References

ACIA (2005) Arctic climate impact assessment. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

AHDR (2004) Arctic human development report. Stefansson Arctic Institute, Akureyri

Anisimov OA, Vaughan DG, Callaghan TV, Furgal C, Marchant H, Prowse TD, Walsh JE (2007) Polar regions (Arctic and Antarctic). In: Parry ML, Canziani OF, Palutikof JP, Van der Linden PJ, Hanson CF (eds) Climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of working group II to the fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 653–685

Armitage D, Berkes F, Dale A, Kocho-Schellenberg E, Patton E (2011) Co-management and the co-production of knowledge: learning to adapt in Canada’s Arctic. Glob Environ Change 21(3):995–1004

Ayers J, Forsyth T (2009) Community-based adaptation to climate change: strengthening resilience through development. Environ Sci Policy Sustain Dev 51(4):22–31

Bates P (2007) Inuit and scientific philosophies about planning, prediction, and uncertainty. Arctic Anthropol 44(2):87–100

Bennett EM, Zurek MB (2006) Integrating epistemologies through scenarios. In: Reid WV, Berkes F, Wilbanks T, Capistrano D (eds) Bridging scales and knowledge systems: concepts and applications in ecosystem assessment. Island Press, Washington, DC, pp 275–294

Berkes F (2012) Sacred ecology, 3rd edn. Routledge, New York, NY

Berkes F, Bankes N, Marschke M, Armitage DR, Clark D (2005) Cross-scale institutions and building resilience in the Canadian North. In: Berkes F, Huebert R, Fast H, Manseau M, Diduck A (eds) Breaking ice: renewable resource and ocean management in the Canadian North. Arctic Institute of North America and University of Calgary Press, Calgary, pp 225–247

Berkes F, Berkes MK, Fast H (2007) Collaborative integrated management in Canada’s North: the role of local and traditional knowledge and community-based monitoring. Coast Manag 35(1):143–162. doi:10.1080/08920750600970487

Bohensky Erin L, Reyers B, Van Jaarsveld AS (2006) Future ecosystem services in a southern African river basin: a scenario planning approach to uncertainty. Conserv Biol 20(4):1051–1061. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00475.x

Bohensky EL, Butler JRA, Mitchell D (2011) Scenarios for knowledge integration: exploring ecotourism futures in Milne Bay, Papua New Guinea. J Mar Biol 2011:1–11. doi:10.1155/2011/504651

Bone R (2009) The Canadian north: issues and challenges, 3rd edn. Oxford University Press, Don Mills, ON

Boyle M, Dowlatabadi H (2011) Anticipatory adaptation in marginalized communities within developed countries. In: Ford JD, Berrang-Ford L (eds) Climate change adaptation in developed nations: from theory to practice. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 461–473

Brock BE, Martin ME, Mongeon CL, Sokal MA, Wesche SD, Armitage DR, Edwards TWD (2010) Flood frequency variability over the past 80 years in the Slave River Delta, NWT, as determined from multi-proxy paleolimnological analysis. Can Water Res J 35(3):281–300

Brooks N, Adger WN, Kelly PM (2005) The determinants of vulnerability and adaptive capacity at the national level and the implications for adaptation. Glob Environ Change 15(2):151–163

Buys L, Miller E, van Megen K (2012) Conceptualising climate change in rural Australia: community perceptions, attitudes and (in)actions. Reg Environ Change 12:237–248

Cajete G (2000) Native science: natural laws of interdependence. Clear Light Publishers, Santa Fe, NM

Canadian Cryospheric Information Network (2005) Future of Canadian permafrost. Retrieved from http://archive-ca.com/page/249696/2012-08-31/http://www.socc.ca/cms/en/socc/permafrost/futurePermafrost.aspx

Carter TR, Jones RN, Lu X, Bhadwal S, Conde C, Mearns LO, Zurek MB (2007) New assessment methods and the characterisation of future conditions. In: Parry ML, Canziani OF, Palutikof JP, Van der Linden PJ, Hanson CF (eds) Climate change 2007: impacts adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of working group II to the fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 133–171

Chapin FS III, Berman M, Callaghan T, Convey P, Crépin AS, Danell K, Zimov SA (2005) Polar systems. In: Hassan R, Scholes R, Ash N (eds) Ecosystems and human well-being: current state and trends. Millennium ecosystem assessment. Island Press, Washington, DC, pp 717–743

Chaudhury M, Vervoort J, Kristjanson P, Ericksen P, Ainslie A (2013) Participatory scenarios as a tool to link science and policy on food security under climate change in East Africa. Reg Environ Change 13(2):389–398. doi:10.1007/s10113-012-0350-1

Cohen SJ (1997a) What if and so what in Northwest Canada: could climate change make a difference to the future of the Mackenzie Basin? Arctic 50:293–307

Cohen SJ (1997b) Mackenzie basin impact study: final report. Environment Canada, Downsview, ON

Couture R, Robinson SD, Burgess MM (2000) Climate change, permafrost degradation, and infrastructure adaptation: preliminary results from a pilot community case study in the Mackenzie Valley. Geological Survey of Canada, Ottawa, ON

Dell CA, Seguin M, Hopkins C, Tempier R, Mehl-Madrona L, Dell D, Mosier K (2011) From Benzos to berries: treatment offered at an Aboriginal youth solvent abuse treatment centre relays the importance of culture. Can J Psychiatry 56(2):75–83

Dodman D, Mitlin D (2013) Challenges for community-based adaptation: discovering the potential for transformation. J Int Dev 25:640–659. doi:10.1002/jid.1772

Duerden F (2004) Translating climate change impacts at the community level. Arctic 57(2):204–212

Enfors EI, Gordon LJ, Peterson GD, Bossio D (2008) Making investments in dryland development work: participatory scenario planning in the Makanya catchment, Tanzania. Ecol Soc 13(2):42. Retrieved from http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol13/iss2/art42/

English MC (1984) Implications of upstream impoundment on the natural ecology and environment of the Slave River Delta, Northwest Territories. In: Olson R, Hastings R, Geddes F (eds) Northern ecology and resource management. The University of Alberta Press, Edmonton, AB, pp 311–339

Environment Canada (2004) Threats to water availability in Canada. NWRI scientific assessment report series no. 3 and ACSD science assessment series no. 1. Retrieved from https://www.ec.gc.ca/inre-nwri/0CD66675-AD25-4B23-892C-5396F7876F65/ThreatsEN_03web.pdf

Faircheallaigh CO (2010) Aboriginal-mining company contractual agreements in Australia and Canada: implications for political autonomy and community development. Can J Dev Stud 2(2010):69–86

Few R, Brown K, Tompkins EL (2007) Public participation and climate change adaptation: avoiding the illusion of inclusion. Clim Policy 7(1):46–59

Fidler C (2009) Increasing the sustainability of a resource development: aboriginal engagement and negotiated agreements. Environ Dev Sustain 12(2):233–244. doi:10.1007/s10668-009-9191-6

Ford JD, Pearce T, Smit B, Wandel J, Allurut M, Shappa K, Qrunnut K (2007) Reducing vulnerability to climate change in the Arctic: the case of Nunavut, Canada. Arctic 60(2):150–166

Ford JD, Keskitalo ECH, Smith T, Pearce T, Berrang-Ford L, Duerden F, Smit B (2010a) Case study and analogue methodologies in climate change vulnerability research. WIREs Clim Change 1:374–392. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/wcc.48/pdf

Ford JD, Pearce T, Duerden F, Furgal C, Smit B (2010b) Climate change policy responses for Canada’s Inuit population: the importance of and opportunities for adaptation. Glob Environ Change 20(1):177–191. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.10.008

Ford JD, Bolton K, Shirley J, Pearce T, Tremblay M, Westlake M (2012) Mapping human dimensions of climate change research in the Canadian Arctic. Ambio 41(8):808–822. doi:10.1007/s13280-012-0336-8

Furgal C, Prowse TD (2008) Northern Canada. In: Lemmen DS, Warren FJ, Lacroix J, Bush E (eds) From impacts to adaptation: Canada in a changing climate 2007. Government of Canada, Ottawa, ON, pp 57–118

Gearheard S, Matumeak W, Angutikjuaq I, Maslanik J, Huntington HP, Leavitt J, Barry RG (2006) “It’s not that simple”: a collaborative comparison of sea ice environments, their uses, observed changes, and adaptations in Barrow, Alaska, USA, and Clyde River, Nunavut, Canada. Ambio 35(4):203–211

Gidley JM, Fien J, Smith J-A, Thomsen DC, Smith TF (2009) Participatory futures methods: towards adaptability and resilience in climate-vulnerable communities. Environ Policy Gov 19:427–440

Handmer J (2003) Adaptive capacity: what does it mean in the context of natural hazards? In: Smith JB, Klein RJT, Huq S (eds) Climate change, adaptive capacity and development. Imperial College Press, London, UK, pp 51–69

Health Canada (2002) Climate change and health and well-being: a policy primer for Canada’s North. Climate Change and Health Office, Ottawa, ON

Hill R, Grant C, George M, Robinson CJ, Jackson S, Abel N (2012) A typology of indigenous engagement in Australian environmental management: implications for knowledge integration and social-ecological system sustainability. Ecol Soc 17(1):23. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-04587-170123

Hoare T (1995) NRBS project report no. 57. Water resources use and management issues for the Peace, Athabasca and Slave River Basins: stakeholder screening survey. Northern River Basins Study, Edmonton, AB

Hovelsrud GK, Smit B (2010) CAVIAR—community adaptation and vulnerability in the Arctic regions. Springer, Dordrecht, Netherlands

Huntington HP (2000) Using traditional ecological knowledge in science: methods and applications. Ecol Appl 10(5):1270–1274

IBA Canada (2011) Important bird areas of Canada: South shore Great Slave Lake (Slave River Delta to Taltson Bay). Retrieved from http://www.bsc-eoc.org:8086/site.jsp?lang=ENsiteID=NT087

IPCC (2007a) Climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of working group II to the fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. In: Parry ML, Canziani OF, Palutikof JP, van der Linden PJ, Hanson CE (eds) Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

IPCC (2007b) Climate change 2007: the physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. In: Solomon S, Qin D, Manning M, Chen Z, Marquis M, Averyt KB, Miller HL (eds) Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

Keeling AM, Sandlos J (2009) Environmental justice goes underground? Historical notes from Canada’s northern mining frontier. Environ Justice 2(3):117–125. Retrieved from http://research.library.mun.ca/406/1/environmental_justice_underground.pdf

Kendall G (1992) Mine closures and worker adjustment: the case of Pine Point. In: Neil C, Tykkylainen M, Bradbury J (eds) Coping with closure: an international comparison of mine town experiences. Routledge, New York, NY, pp 131–150

Keskitalo ECH, Kulyasova AA (2009) The role of governance in community adaptation to climate change. Polar Res 28(1):60–70. doi:10.1111/j.1751-8369.2009.00097.x

Kok K, Biggs R, Zurek MB (2007) Methods for developing multiscale participatory scenarios: insights from Southern Africa and Europe. Ecol Soc 13(1):8. Retrieved from http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol12/iss1/art8/

Krupnik I, Jolly D (2002) The earth is faster now: indigenous observations of Arctic environmental change. Arctic Research Consortium of the United States, Fairbanks, AK

Laidler GJ (2006) Inuit and scientific perspectives on the relationship between sea ice and climate change: the ideal complement? Clim Change 78:407–444

Lemmen DS, Warren FJ (2004) Climate change impacts and adaptation: a Canadian perspective. Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation Directorate, Natural Resources Canada, Ottawa, ON

Lemmen DS, Warren FJ, Lacroix J, Bush E (2008) From impacts to adaptation: Canada in a changing climate 2007. Government of Canada, Ottawa, ON. Retrieved from adaptation2007.nrcan.gc.ca

Miller KD, Waller HG (2003) Scenarios, real options and integrated risk management. Long Range Plan 36(1):93–107

Nakićenović N (2000) Greenhouse gas emissions scenarios. Technol Forecast Soc Change 65:149–166

Nickels S, Furgal C, Buell M, Moquin H (2006) Unikkaaqatigiit—putting the human face on climate change: perspectives from Inuit in Canada. Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, Nasivvik Centre for Inuit Health and Changing Environments, Ajunnginiq Centre (NAHO), Ottawa, ON

Northwest Territories Bureau of Statistics (2007) Fort Resolution—statistical profile. NWT community profiles, Yellowknife, NT

O’Brien K, Leichenko R (2000) Double exposure: assessing the impacts of climate change within the context of economic globalization. Glob Environ Change 10(3):221–232

O’Brien KL, Wolf J (2010) A values-based approach to vulnerability and adaptation to climate change. WIREs Clim Change 1:232–242. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/wcc.30/pdf

Odada EO, Ochola WO, Olago DO (2009) Understanding future ecosystem changes in Lake Victoria basin using participatory local scenarios. Afr J Ecol 47(Suppl. 1):147–153

Ogden AE, Innes J (2007) Incorporating climate change adaptation considerations into forest management planning in the boreal forest. Int For Rev 9(3):713–733. doi:10.1505/ifor.9.3.713

Pearce TD, Ford JD, Laidler GJ, Smit B, Duerden F, Allarut M, Wandel J (2009) Community collaboration and climate change research in the Canadian Arctic. Polar Res 28:10–27

Pearce T, Ford JD, Duerden F, Smit B, Andrachuk M, Berrang-Ford L, Smith T (2010) Advancing adaptation planning for climate change in the Inuvialuit settlement region (ISR): a review and critique. Reg Environ Change 11(1):1–17. doi:10.1007/s10113-010-0126-4

Peterson GD (2007) Using scenario planning to enable an adaptive co-management process in the Northern Highlands Lake District of Wisconsin. In: Berkes F, Armitage DR, Doubleday NC (eds) Adaptive co-management: collaboration, learning, and multi-level governance. UBC Press, Vancouver, pp 289–307

Peterson GD, Beard Jr. TD, Beisner BE, Bennett EM, Carpenter SR, Cumming GS, Havlicek, TD (2003a) Assessing future ecosystem services: a case study of the Northern Highlands Lake District, Wisconsin. Conserv Ecol 7(3). Retrieved from http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol7/iss3/art1/

Peterson GD, Cumming G, Carpenter S (2003b) Scenario planning: a tool for conservation in an uncertain world. Conserv Biol 17(2):358–366

Polasky S, Carpenter SR, Folke C, Keeler B (2011) Decision-making under great uncertainty: environmental management in an era of global change. Trends Ecol Evol 26(8):398–404. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2011.04.007

Prowse TD, Conly FM, Church M, English MC (2002) A review of hydroecological results of the Northern River Basins Study, Canada. Part 1. Peace and Slave rivers. River Res Appl 18(5):429–446

Prowse TD, Beltaos S, Gardner JT, Gibson JJ, Granger RJ, Leconte R, Toth B (2006) Climate change, flow regulation and land-use effects on the hydrology of the Peace-Athabasca-Slave system; Findings from the Northern Rivers Ecosystem Initiative. Environ Monit Assess 113(1–3):167–197

Raymond CM, Fazey I, Reed MS, Stringer LC, Robinson GM, Evely AC (2010) Integrating local and scientific knowledge for environmental management. J Environ Manag 91:1766–1777

Reed MS, Fazey I, Stringer LC, Raymond CM, Akhtar-Schuster M, Begni G, Bigas H, Brehm S, Briggs J, Bryce R, Buckmaster S, Chanda R, Davies J, Diez E, Essahli W, Evely A, Geeson N, Hartmann I, Holden J, Hubacek K, Ioris AAR, Kruger B, Laureano P, Phillipson J, Prell C, Quinn CH, Reeves AD, Seely M, Thomas R, Van Der Werff Ten Bosch MJ, Vergunst P, Wagner L (2013) Knowledge management for land degradation monitoring and assessment: an analysis of contemporary thinking. Land Degrad Dev 24:307–322

Riewe R, Oakes J (2006) Climate change: linking traditional and scientific knowledge. Aboriginal Issues Press, Winnipeg, MB

Rouse WR, Douglas MSV, Heckey RE, Hershey AE, Kling GW, Lesack L, Smol JP (1997) Effects of climate change on the freshwaters of Arctic and Subarctic North America. Hydrol Process 11:873–902

Sheppard SRJ, Shaw A, Flanders D, Burch S, Wiek A, Carmichael J, Cohen S (2011) Future visioning of local climate change: a framework for community engagement and planning with scenarios and visualisation. Futures 43(4):400–412. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2011.01.009

Smit B, Skinner MW (2002) Adaptation options in agriculture to climate change: a typology. Mitig Adapt Strat Glob Change 7:85–114

Waltner-Toews D, Kay JJ, Neudoerffer C, Gitau T (2003) Perspective changes everything: managing ecosystems from the inside out. Front Ecol Environ 1(1):23–30

Warren FJ, Egginton PA (2008) Background information: concepts, overviews and approaches. In: Lemmen DS, Warren FJ, Lacroix J, Bush E (eds) From impacts to adaptation: Canada in a changing climate 2007. Government of Canada, Ottawa, ON, pp 27–56

Wesche SD (2009) Responding to change in a Northern Aboriginal community (Fort Resolution, NWT, Canada): linking social and ecological perspectives. Geography and environmental studies. Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, ON

Wesche SD, Armitage DR (2010a) “As long as the sun shines, the rivers flow and the grass grows”: vulnerability, adaptation and environmental change in Deninu Kue Traditional Territory, Northwest Territories. In: Hovelsrud GK, Smit B (eds) CAVIAR—community adaptation and vulnerability in the Arctic regions. Springer, Dordrecht, Netherlands, pp 163–189

Wesche SD, Armitage DR (2010b) From the inside out: a multi-scale analysis of adaptive capacity in a northern community and the governance implications. In: Armitage DR, Plummer R (eds) Adaptive capacity: building environmental governance in an age of uncertainty. Springer, Heidelberg, Germany, pp 107–132

Wesche SD, Schuster R, Tobin P, Dickson C, Matthiessen D, Graupe S, Chan HM (2011) Community-based health research led by the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation. Int J Circumpolar Health 70(4):396–406

Wolfe BB, Armitage DR, Wesche SD, Brock BE, Sokal MA, Clogg-Wright KP, Edwards TWD (2007) From isotopes to TK interviews: towards interdisciplinary research in Fort Resolution and the Slave River Delta, Northwest Territories. Arctic 60(1):75–87

Wollenberg E, Edmunds D, Buck L (2000) Using scenarios to make decisions about the future: anticipatory learning for the adaptive co-management of community forests. Landsc Urban Plan 47(1–2):65–77. doi:10.1016/S0169-2046(99)00071-7

WWF (2008) Arctic climate impact science—an update since ACIA. WWF International Arctic Programme, Oslo, Norway. Retrieved from http://assets.panda.org/downloads/final_climateimpact_22apr08.pdf

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the support and participation of DKFN Chief and Council, the DKFN Environment Manager, the Metis Local, Fort Resolution research assistants and community members, Deninu Kue School, the family of Dollie and Raymond Simon, Elise Vos and Matt Albrecht. Financial support for this research project was provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, Natural Resources Canada Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation Program, the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada Northern Scientific Training Program, the Ocean Management Research Network Integrated Management Node Student Seed Grant, and the Association of Canadian Universities for Northern Studies Canadian Polar Commission Scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Wesche, S.D., Armitage, D.R. Using qualitative scenarios to understand regional environmental change in the Canadian North. Reg Environ Change 14, 1095–1108 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-013-0537-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-013-0537-0