Abstract

Adaptation is a key component of climate policy, yet we have limited and fragmented understanding of if and how adaptation is currently taking place. In this paper, we document and characterize the current status of adaptation in 47 vulnerable ‘hotspot’ nations in Asia and Africa, based on a systematic review of the peer-reviewed and grey literature, as well as policy documents, to extract evidence of adaptation initiatives. In total, 100 peer-reviewed articles, 161 grey literature documents, and 27 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change National Communications were reviewed, constituting 760 adaptation initiatives. Results indicate a significant increase in reported adaptations since 2006. Adaptations are primarily being reported from African and low-income countries, particularly those nations receiving adaptation funds, involve a combination of groundwork and more concrete adaptations to reduce vulnerability, and are primarily being driven by national governments, NGOs, and international institutions, with minimal involvement of lower levels of government or collaboration across nations. Gaps in our knowledge of adaptation policy and practice are particularly notable in North Africa and Central Asia, and there is limited evidence of adaptation initiatives being targeted at vulnerable populations including socioeconomically disadvantaged populations, children, indigenous peoples, and the elderly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Developing nations are believed to be particularly susceptible to the impacts of climate change (IPCC 2014; Patt et al. 2010; World Bank 2010). This derives from the dependence of livelihoods on climate-sensitive sectors such as agriculture, tourism, fisheries, and forestry, climate-sensitive infrastructure such as houses, buildings, municipal services, and transportation networks, and limited adaptive capacity to cope with impacts. Not all developing nations are equally vulnerable to climate change; however, a function of exposure to projected changes and socioeconomic factors determine sensitivity and adaptive capacity (IPCC 2014). The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), for example, recognizes low-lying and small island developing nations to be particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change and recognizes the special needs of least developed countries (LDCs). These high-risk regions are primarily located in sub-Saharan Africa, and to a lesser extent south Asia, with vulnerabilities associated with increased water stress, coastal inundation, changes in river hydrology, increased exposure to infectious disease, and alterations to the magnitude and frequency of extreme events (IPCC 2007; World Bank 2010) (see DaSouza et al. and Kilroy in this special edition).

In absence of targeted action, climate change is expected to significantly undermine the socioeconomic progress made in developing nations, especially the poorest, compounding ongoing development challenges (Costello et al. 2009; World Bank 2010). The need for adaptation has been widely recognized among developing countries since UNFCCC negotiations began in the early 1990s and has received renewed impetus in light of recognition of the now inevitable changes in climate. Herein, significant advances in adaptation have been made over the last decade, including the establishment and disbursement of adaptation funds through the UNFCCC, completion of National Adaptation Programs of Action (NAPAs), initiation of National Adaptation Plans (NAPs), mainstreaming of adaptation into development projects, and the emergence of a large body of scholarship examining vulnerability to help direct adaptation efforts (Berrang-Ford et al. 2011; Biagini et al. 2014; Fankhauser and Burton 2011; Mannke 2011; Sovacool 2012; Sovacool et al. 2012a).

Despite the increasing importance of adaptation, we have limited and fragmented understanding of if and how adaptation is currently taking place, with the majority of adaptation research and debate identifying adaptation needs, characterizing vulnerability, and developing methodological frameworks (Ford et al. 2013; Sovacool 2012; Sovacool et al. 2012a; Surminski 2013). A number of studies have begun to examine the status of adaptation actions and indicate that while adaptation has appeared on the political agenda, implementation is lacking, with policies often labeled as ‘adaptation’ having limited concrete effects on reducing vulnerability or reflecting rebranding of existing policies focused on risk reduction (Berrang-Ford et al. 2011, 2014, Biesbroek et al. 2010; Dupuis and Biesbroek 2013; Ford and King in press; Ford et al. 2011; Gagnon-Lebrun and Agrawala 2007; Hanger et al. 2013; Lesnikowski et al. 2011, 2013). Research characterizing the current status of adaptation remains in its infancy, however, focusing primarily on high-income nations, using a limited number of data sources, and/or piloting methodologies for adaptation tracking. This gap in understanding on the status of adaptation is part of a broader ‘adaptation deficit’ and constrains our ability to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of policies to promote adaptation, prioritize the adaptation efforts that work best, and inform adaptive governance at various levels on adaptation needs (Brooks et al. 2011; Ford and King in press; Mannke 2010, 2011; Preston et al. 2011; Sovacool et al. 2012b).

This paper is situated within the context of this deficit in understanding and identifies and characterizes trends in adaptation in 47 countries in Asia and Africa. These nations are the focus of this special edition, are profiled in the first paper in the volume (DaSouza et al. in this volume), and are referred to here as climate change ‘hotspot’ countries consistent with the special edition. The focus on these nations partly reflects their vulnerability to climate change. There also remain large gaps in understanding of the state of adaptation in Africa and Asia generally. The assessment reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and other climate assessments (e.g., Costello et al. 2009; World Bank 2010), for instance, provide selected examples of adaptation in action, as do a variety of adaptation databases (e.g., africa-adapt.net, weadapt.org), but do not systematically and comprehensively compile and assess information on current actions. Other studies examine adaptations supported by specific funding schemes, but provide only snapshots of broader trends: Mannke (2011), for example, evaluates community-based adaptation initiatives in Africa, Sovacool (2012), examine adaptation projects supported through the LDC fund in four nations in southeast Asia, and Sherman and Ford (2014) examine adaptations supported through three of the Global Environment Facility’s adaptation funds. This paper generates a baseline understanding of the current status of adaptation in climate change hotspot countries in Africa and Asia. The work is complemented by in-depth consideration of specific regions and topics in the accompanying articles of this special edition, which were together commissioned by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) and Canada’s International Development Research Centre (IDRC) to inform the development of their Collaborative Adaptation Research Initiative in Africa and Asia (CARIAA) program.

Methods

Data collection

We characterize the current status of adaptation policy and practice in 47 hotspot countries in Africa and Asia using publically available information published between January 2006 and October 2012. Literature prior to 2006 is excluded as this is covered by IPCC assessment reports; the October 2012 cut-off reflects when the study was begun. Three data sources are used: the peer-reviewed literature, grey literature (e.g., reports by consultants, governments, NGOs.), and National Communications (NCs) to the UNFCCC. NAPAs were also considered for inclusion, but were excluded since they generally reflect proposals or ‘wishlists’ for adaptation rather than concrete policy or practices. The NCs were selected as a key data source for this review to provide a systematic and standardized source for adaptation policy across nations. NCs contain information on climate change mitigation, vulnerability, impacts, adaptation, and climate policies and programming and have been used successfully to track progress and trends in adaptation elsewhere (see Lesnikowski et al. in press; Lesnikowski et al. 2011 for further detail on strengths of using NCs as a data source).

A systematic literature review approach was used to identify relevant literature pertaining to adaptation policy and practice in hotspot countries according to explicitly formulated criteria as outlined in supplementary materials and building upon recent methodological advances on the use of systematic reviews in an environmental change context (Berrang-Ford et al. 2011; Biesbroek et al. in press; Ford and Pearce 2010; Lesnikowski et al. 2011; Lorenz et al. 2014; McDowell et al. in press; McLeman 2011) (also see Berrang-Ford et al. in this special edition). Full details on the review protocol and procedures are found in supplementary materials. The review focused on identifying human adaptation actions explicitly identified within the documents as adaptations purposefully targeted at climate change impacts and designed to reduce vulnerability and/or enhance resilience, as per IPCC. Herein, adaptation or adaptive strategies in the context of human dimensions of climate change refers to adjustments in human systems in response to actual or expected climatic stimuli or their effects, which moderate harm or exploit beneficial opportunities. As such, we recognize that focusing on adaptations explicitly recognized and reported in relationship with a climate stimuli or event may, in some cases, overlook actions designed to address underling determinants of vulnerability, underscoring our interpretation of the results as a proxy of adaptation (see ‘Discussion’).

Within the peer-reviewed literature, the search terms ‘climat* change’ OR ‘global warming’ were combined with country names and a range of geographical descriptors within the search engines Web of Knowledge and Scopus to identify relevant literature. Initial searches yielded approximately 2,000 hits. Titles and abstracts were screened based our inclusion/exclusion criteria (see supplementary materials). In some cases, full text review was required to confirm eligibility for inclusion. 684 documents met initial relevance screening criteria and underwent a full text screen. 100 documents were considered relevant after full text screen and underwent data extraction.

Relevant grey literature was identified using two focused searches in Google, focusing on Asia and Africa separately. This was designed since hits were dominated by activities based on Africa, and we aimed to gather a sufficient sample of activities in both regions. To limit hits to a manageable number and to apply a preliminary and coarse quality filter, we restricted included documents to.pdf files only. We used the following search terms:

-

1.

“climat* change” adapt* Asia (outcome OR action OR strategy OR plan OR “risk reduction”) AND (“semi-arid” OR “delta” OR “river basin”) -China filetype:pdf.

-

2.

“climat* change” adapt* Africa (outcome OR action OR strategy OR plan OR “risk reduction”) AND (“semi-arid” OR “delta” OR “river basin”) filetype:pdf.

The title and description provided within the standard Google search engine were reviewed to determine the relevance of each result. To achieve a manageable number of hits and a representative sample of the grey literature, after 25 consecutive irrelevant results, we skipped ahead 50 results and 5 more results were reviewed for relevance (Furgal et al. 2010). This process continued until the 600th result. Six hundred results from each search were uploaded to EppiReviewer, for a total of 1,200 documents meeting initial relevance screening. A first page screen was applied to confirm eligibility using our inclusion/exclusion criteria, resulting in 799 documents. Following full text review, a total of 161 grey literature documents were retained and underwent data extraction.

National Communications (NCs) for hotspot countries were extracted from the UNFCCC website (http://unfccc.int/national_reports/non-annex_i_natcom/items/2979.php). NCs were included in our review if published on or after January 1, 2006. Of the 47 hotspot countries, 27 had NCs available for 2006 or later at the time of study. All were available in English or French. The remaining 20 countries had either no NC available or had an NC that was not sufficiently recent (2006 or later) to be included.

Data extraction and analysis

Data extraction was based on a common data codebook (see supplementary materials) for all three data sources (peer reviewed, grey, and NCs). As per Lesnikowski et al. (in press), and in order to account for variations in reporting on adaptation policy and practice between different document types, data were extracted using discrete adaptation initiatives as a unit of observation. While some peer-reviewed articles only presented and summarized one adaptation action or policy (here referred to as an adaptation initiative), other documents such as the NCs or grey literature reports provided comprehensive summaries of multiple adaptation initiatives. The following variables were collected for each unique reference or initiative: year of publication, author affiliation, country, sectoral involvement, scale and type of adaptation, implementing group, goal of adaptation, stakeholder engagement, and vulnerable population focus, as documented in supplementary materials and informed by adaptation assessment frameworks proposed by Smith et al. (2000).

Adaptations were categorized as being either groundwork actions or adaptation actions (Lesnikowski et al. in press). Groundwork actions are considered first steps necessary to inform and prepare for adaptation, but do not explicitly indicate tangible changes in policy or delivery of government services that improve resilience. These types of action consist of impact and vulnerability assessments, research on adaptation options, conceptual tools, stakeholder and networking opportunities, and recommendations for adaptation action. Their inclusion in the analysis reflects the fact that groundwork actions are often a precursor to full adaptation and have an important role in government planning (Lesnikowski et al. 2011). Adaptation actions are understood as concrete changes made to intentionally reduce vulnerability/increase adaptive capacity to climate change. They include introduced and substantial initiatives such as changes made to built environments, the delivery of government services, organizational mandates, or regulations in response to predicted or experienced impacts of climate change. The distinction between these two levels of adaptation is important, bringing clarity for what we view as adaptation initiatives, and providing a proxy for differentiating responses according to how substantial actions are in targeting climate change vulnerability reduction.

Full text documents were reviewed for peer-reviewed and grey literature. In the case of NCs, we reviewed only the text within the section on impacts, vulnerability and adaptation, focusing on any text related to adaptation. Descriptive statistics are used to present quantitative trends on adaptation initiatives reported in the literature. Analysis also involved identifying the top 20 and bottom 20 adaptors, based on number of adaptations reported, noting that reporting on adaptation was not influenced by country size, or whether a nation had completed an NC. This enabled us to characterize key differences between high and low adaptors in the dataset, as well as explore differences in country characteristics. This involved comparing the dataset with: (1) vulnerability indicators derived from the GAIN vulnerability index, from which the top 20 most vulnerable nations were identified. GAIN was chosen because of its comprehensive coverage of hotspot countries and comparability with other indices, (2) economy classifications according to the World Bank (low income, lower-middle income, upper-middle income), and (3) data on international finance for adaptation obtained from the Climate Funds Update (CFU 2012) and screened for the top and bottom 20 nations in the hotspot regions for receiving adaptation funds. Chi-squared and Fishers exact tests were conducted to test for associations between adaptation initiatives and country characteristics, with significance reported at 95 %. Unless otherwise specified, p values are based on a chi-squared test.

Results

Documented adaptation initiatives have increased significantly since 2006

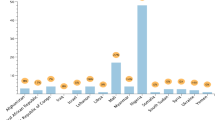

Of the 2,084 publications from the peer-reviewed and grey literature selected for initial review, 261 were retained for analysis as reporting adaptation initiatives and were joined by NCs from 27 countries. 288 documents were reviewed altogether, and we identified and coded 760 unique adaptation initiatives (see supplementary materials). Within the NCs, 189 initiatives were reported, ranging from one initiative in Gabon to 25 in South Africa and averaging 7 per country. On average, peer-reviewed articles included 1–2 adaptation initiatives (for a total of 150 documented initiatives), while grey literature documents reported 2–3 (for a total of 421 documented initiatives). There has been notable growth in reporting on adaptation initiatives in hotspot countries included in the analysis, across all literature types (Fig. 1; Table 1). The peer-reviewed literature describing adaptation has emerged predominantly since 2008 and has grown rapidly.

Adaptation initiatives are predominantly being reported from African and low-income countries

Despite our stratification of the grey literature review process to increase literature sampled for Asia, reporting from southern and eastern African nations remained dominant with the exception of key Asian nations, namely India, Bangladesh, and Nepal (Table 2). Close to three quarters (n = 562, 74 %) of all adaptation initiatives recorded are from African nations (Fig. 1), with 24 % (n = 195) from Asian countries included in the analysis (Fig. 1). Among our sample, on a population basis, there are 0.67 initiatives per million people in the African nations compared with 0.12 in Asia. This proportion has not changed substantively since 2006. The highest number of documented adaptation initiatives was reported in Kenya (n = 59), followed by Ethiopia (n = 54), India (n = 51), South Africa (n = 42), Bangladesh (n = 41), Malawi (n = 40), and Rwanda (n = 36) (see supplementary materials).

There is a notable absence of reporting on adaptation in Central Asia. There was no NC available for Afghanistan at the time of review, although one has since been submitted in March 2013, and only one peer-reviewed article (Krysanova et al. 2010). Only two grey literature documents by international organizations were available (UNEP 2011; WFP 2011), and no reporting by formal government structures. While NCs were available and reviewed for Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, peer-reviewed literature on adaptation in these nations is limited. Only a few grey literature documents led by international organizations and NGOs were available for the region in general (International C 2008; IOM 2009b; RECCA 2011; World Bank 2008, 2011), and two journal articles also general to the region (Krysanova et al. 2010; Stucker et al. 2012). NC content is limited to a few vulnerability assessments, with the exception of Uzbekistan, which has gone beyond groundwork initiatives to develop preliminary health care adaptation projects and a drought early warning system. All Central Asian nations—except for Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan—have fewer than 10 documented adaptation initiatives (Fig. 1).

Table 2 identifies the top and bottom 20 nations reporting adaptation initiatives and compares these nations with the most vulnerable countries in the hotspot regions identified in the GAIN vulnerability index. Over half (n = 11) of the most vulnerable nations from GAIN are among the top adaptors documented in this study. However, 30 % (n = 6) of the most vulnerable nations are also among the lowest adaptors based on reported adaptations. Interestingly, low-income countries were significantly more likely (p = 0.02, Fisher’s exact test) to be top adaptors: 74 % of the top 20 adaptors were low-income nations compared with 36 and 14 % for lower-middle and upper-middle-income nations, respectively. Liberia and Afghanistan are notable outliers. Comparing data on international finance for adaptation with documented adaptations for the hotspot regions reveals that those topping funding are more likely (p = 0.03, Fishers exact test) to be top adaptors (80 vs 39 %), while 61 % of bottom funders were low adapters compared with only 20 % of top funders.

Initiatives involve a combination of groundwork and more concrete adaptation actions

Of the 760 adaptation initiatives documented, 48 % were classified as groundwork and 52 % adaptation actions (Table 2). This proportion has changed little since 2006. Nations reporting the highest number of adaptations were also leaders in implementing concrete adaptations designed to intentionally reduce vulnerability/increase adaptive capacity to climate change, including Kenya (n = 34), India (n = 32), Ethiopia (n = 29), Bangladesh (n = 25), Mozambique (n = 22), and Ghana (n = 20). Mali (n = 16), Namibia (n = 7), Nepal (n = 17), Senegal (n = 14), Sudan (n = 15), Uganda (n = 19), and Zimbabwe (n = 12), were notable for reporting substantially more actions than groundwork. Nations reporting few adaptations have made limited progress on implementing adaptation actions. There are no significant differences between region (i.e., Africa vs. Asia) in the reporting of groundwork versus adaptation actions.

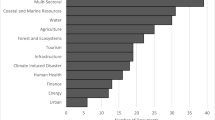

Agriculture is the dominant focus of reported adaptation initiatives

Close to one-third of all adaptation initiatives documented related to agriculture (n = 220, 29 %) (Table 1), involving a mix of groundwork and adaptation actions. Agriculture was a key focus across countries, but particularly those with semi-arid regions. Initiatives include, for example, national assessments of impacts and adaptation opportunities within the agricultural sector, institutional guidelines for adaptation, and recommendations or public awareness program for adaptive measures to reduce risk (for example, see NCs for India, Namibia, South Africa, Egypt, DRC, and Mauritania). Reporting of sub-national initiatives on agriculture is predominantly found in the grey literature and includes programs led by international organizations and NGOs to identify, implement, and evaluate adaptations to increase resiliency and reduce vulnerability within the agricultural sector (ATPSN 2011; FAO 2011a, b; IIED 2010; World Bank 2011). In many cases, local adaptations or mechanisms for dealing with agricultural variability are used as a proxy for adaptive capacity and resiliency within agricultural livelihood systems. Research by the International Institute for Environment and Development in Niger, for example, has focused on identifying existing community ‘champions’ representing local agricultural adaptations already present in the region to build on and promote existing adaptive capacity mechanisms, as well as engaging in print and electronic media to disseminate adaptation options available to communities in Ghana (IIED 2010).

Other key foci of documented adaptation initiatives include disaster and risk management (n = 114, 15 %), which was a top priority for adaptation in large river basins, with an emphasis on flood management (GIZ 2011; IOM 2009a; WFP 2011; also see NCs for Bhutan, South Africa). Nations with low-lying deltas also emphasized initiatives related to agriculture and disaster risk management. Disaster management is dominated by flood mitigation initiatives, including programs to reduce the likelihood of floods (soil stabilization, crop diversification), improve forecasting (early warning systems), and providing support during flooding events (emergency health care, radio communications, communication networks). Uzbekistan, for example, has developed a drought early warning system as part of a broader national program to reduce hazard vulnerability and manage climate risk. This includes programming to reform insurance markets to integrate climate risk (see Uzbekistan NC). Interestingly, infrastructural based adaptations (e.g., flood protection) were not widely reported. While disaster management figured prominently in adaptation reporting, nations with a high vulnerability to natural disasters according to the GAIN index with no strategic disaster-related adaptation identified at the national level included the Democratic Republic of Congo, Togo, Namibia, Sierra Leone, and Rwanda. Most disaster reporting is by international institutions and NGOs such as the World Bank, UNDP, UNEP, CARE. Initiatives associated with the management, extraction, treatment, storage, distribution and general use of water, were also well documented (n = 100, 13 %).

Key sectors lagging on reported adaptation initiatives include public health, which was identified as a priority for adaptation in the NCs, yet few, primarily groundwork, adaptations specifically target the health effects of climate change (n = 32, 4 %). Reporting on health adaptations is highest in the NCs, where it accounts for 15 % of adaptation initiatives. The peer-reviewed and grey literature have a marginal focus on health adaptation (<1 %) (Table 1). These results may reflect differing jurisdictions among sectors, where health often falls under national jurisdiction and may thus be overrepresented within the NC documents. This lack of translation of national policy priorities is further seen in our recording of primary author affiliation within the peer-reviewed literature. Of adaptation initiatives reported here, primary author affiliations are primarily based in the social (~60 %) and physical (~40 %) sciences. No documents were identified with primary author affiliation in health sciences.

Adaptation initiatives are being primarily driven at the national level, with minimal involvement of lower levels of government or collaboration across nations

Documented adaptation initiatives are primarily being developed and led by national governments (n = 202, 26 %), international institutions (e.g., UN-bodies) (n = 178, 23 %), and non-governmental organizations (n = 158, 21 %). There is minimal involvement of lower levels of government in leading the development of adaptations profiled here, including at the municipal level (n = 15, 2 %) and at the state/provincial level (n = 3, <1 %) (Table 1). The private sector was absent in adaptation reporting, with fewer than 1 % of all initiatives implemented within the private sector. Notably, given the trans-boundary nature of a number of key risks facing the hotspot regions, adaptations taken in partnership between two or more nations by government, NGOs, or international institutions were documented in only 23 (3 %) cases. Eight of these involved water management, focusing on large African rivers including the Nile, Limpopo, Orange, and Niger, and one focused on the Amudarya basin in Central Asia. These are all groundwork adaptations, evaluating legal, technical and economic policies/procedures for water resource management in light of climate change. Adaptation initiatives involving national government were primarily groundwork in nature (76 %), compared with those led by international institutions and NGOs which involved adaptation actions (67, 70 %).

Adaptation initiatives incorporate a mix of proactive and reactive responses varying by sector

Approximately 45 % (n = 342) of initiatives were planned or anticipatory actions, reflecting explicit intent to plan for anticipated climate change impacts (Table 1). Examples include implemented forecasting/warnings, development or revision of sectoral policies and programs, creation or revision of insurance programs, and the establishment of management bodies to assess and prepare for climate change impacts. 55 % (n = 408) of documented initiatives were reactive in nature, taken in response to impacts/stressors that have already been observed, and representing actions to cope with immediate impacts or to adjust to an altered environment. Reported adaptations were more likely to be proactive in the water sector (63 %, p < 0.01), and less likely to be less proactive in agriculture (37 %, p < 0.01), ecosystem services (22 %, p < 0.01), and disaster and risk management (33 %, p < 0.01) sectors. Adaptations were significantly more reactive among those implemented by NGOs (80 %, p < 0.01), international institutions (74 %, p < 0.01), and individuals/households or communities (83 %, p < 0.01). In contrast, adaptations by national governments are more frequently proactive (87 %, p < 0.01). Regionally, Asian nations were more likely to report proactive adaptations than those in Africa (53 vs. 43 %, p = 0.01), reflecting the greater role of national governments in adaptations documented in Asia. Notably, fewer than 1 % of adaptations emphasized taking advantage of climate change benefits.

There is negligible consideration of vulnerable groups in adaptation initiatives

Adaptation initiatives, in general, poorly integrated consideration of vulnerable groups (Table 2). Approximately one-fifth of documented initiatives considered socioeconomically disadvantaged populations, while one in ten considered the vulnerability of women. There was limited consideration of vulnerability among children, the elderly, or Indigenous populations. A number of documents noted that women in particular were not only more vulnerable to impacts, but may also be disadvantaged in access to adaptation resources and have lower success rates for adaptation initiatives. Djoudi and Brockhaus (2011), for example, report on lessons from communities dependent on livestock and forests in northern Mali, asking whether adaptation to climate change is gender neutral. They note substantive disparities in women’s ability to engage in and take adaptive action. In most cases where women are described as a vulnerable group in reports of adaptation action, however, there is limited evidence that this vulnerability is directly guiding the design and implementation of the adaptation policies or practices. In some cases, however, initiatives are clearly and explicitly targeted toward the gender dimensions of adaptation. Gippner et al. (2012), for example, describe a micro-hydro-electrification project undertaken in Nepal with the explicit goal of female participation and improving adaptive capacity among women.

Several NCs from southern and eastern Africa include special attention to women in programing, particularly including Malawi, Namibia, and Eritrea. Consideration of the gendered dimensions of adaptation policy and practice was more commonly reported in African nations, and notably limited in Central Asia and North African countries. Consideration of women as a vulnerable group also differed among initiatives depending on the implementing group. NGOs and institutional organizations most often considered gender vulnerabilities (14 and 17 %, respectively). In contrast, only 5 % of national government initiatives considered the vulnerability of women.

The profile of adaptation initiatives differs between data sources

Together the three data sources used in this article create a comprehensive inventory of adaptation initiatives in the hotpot nations. It is noteworthy, however, that the profiles of reported adaptations differed significantly between the peer-reviewed, grey, and NC literature (Table 1; Fig. 2). NCs are predominantly reporting initiatives at the national level and are dominated by groundwork activities such as vulnerability assessments prepared for or by national ministries and national plans of action. NC initiatives tend to respond to proactive goals such as preparing for climate impacts, and enhancing learning and research. The peer-reviewed literature, in contrast, actively reports on predominantly reactive adaptation in practice, with emphasis on the individual, household, and community levels. Goals of initiatives in the peer-reviewed literature are primarily reactive, including adjusting, accommodating, or coping with climate impacts. Grey literature documents were more mixed, and contain substantive consideration of initiatives led by civil society organizations and international institutions which were relatively absent from the NCs or peer-reviewed literature.

Discussion

We establish a baseline understanding of the current state of adaptation in 47 ‘hotspot’ nations of Africa and Asia based on reporting on adaptation initiatives in the peer-reviewed and grey literature, and in policy documents. The methodology extends previous work identifying and characterizing the state of adaptation at regional to global levels, which has typically utilized single data sources. A key strength of the approach is its ability to systematically characterize the current state of adaptation using existing sources of information, and is particularly suited for comparative analysis between and across regions and sectors, for identifying general trends and patterns, and examining progress over time. We underscore that our results are indicative of general trends and are not intended to guide country-level policy development, with more detailed information specific to regions and nations provided in other articles in this special edition.

Caution is also needed when interpreting the results as many adaptations are undocumented, while the detail provided in documents can vary greatly, reflecting reporting as much as actual experience with adaptation. Furthermore, in many instances adaptations to climate change are unlikely to be undertaken for climate change alone but are more likely to be a response to problematic conditions that already exist. Supporting efforts that address poverty, financial inequalities, health, education, and cultural capacity will often inadvertently enhance the adaptive capacity of peoples to deal with current and expected future climate change risks. These initiatives would not have been captured in the review unless there was an explicitly recognized and reported relationship with a climate stimuli or event. It is also noteworthy that given the broad scale focus of the analysis, we do not directly examine effectiveness or potential success of adaptations, acknowledging that not all adaptations are equal and some may be ineffective or actually increase vulnerability. Nevertheless, adaptation reporting offers an indicator or proxy of the status of adaptation by which initiatives can be inventoried and evaluated, providing a snapshot of what is going on (Lesnikowski et al. in press; Ford and King in press). The extent of current action can be established with reference to the number of adaptation initiatives taking place, while adequacy and strength of initiatives can be examined via the nature of adaptations reported and compared with commitments and needs identified to give an indication of potential effectiveness/success. Similar approaches have been successfully used to examine mitigation policy, such as the Globe Climate Legislation Initiative (Townshend et al. 2013), and more broadly to compare and monitor health policy (Ford and King in press; Poutiainen et al. 2013). In the discussion below, we identify important trends emerging from the hotspot countries.

Firstly, there is evidence that discernible progress is being made on adaptation. This can be observed in the rapid increase in reporting of adaptation since 2006, diversity of organizations and institutions involved, range of countries reporting to be engaging in adaptation, and responses being undertaken in climate-sensitive sectors including agriculture, disaster management, and water. While it is not possible to make judgments on the state of adaptation solely on the increasing number of reported initiatives, it is nevertheless indicative of adaptation being taken more seriously in climate policy.

Another important indicator of progress is the number of reported adaptations that have been designed to intentionally and proactively address climate change vulnerabilities (i.e., adaptation actions). This is in contrast to previous work which has highlighted a predominance of groundwork actions in adaptive response both globally and in high-income nations, with a focus on assessing vulnerability, supporting stakeholder workshops, developing tools, making recommendations, etc. (Berrang-Ford et al. 2011; Ford et al. 2011; Gagnon-Lebrun and Agrawala 2007; Lesnikowski et al. in press, 2011). Groundwork actions represent critical first steps for adaptation, and were widely documented among nations here, but are unlikely to be sufficient to moderate the effects of climate change on their own. Concerns have also been expressed in the scholarship that policies labeled as ‘adaptation’ are not substantively targeting vulnerabilities linked to climate change, which it has been argued is problematic in light of the scale and magnitude of projected climate change impacts (Adger and Barnett 2009; Dupuis and Biesbroek 2013; O’Brien 2012). This study, however, demonstrates that for some regions and sectors, adaptation actions are taking place.

Progress on adaptation, however, based on analysis of reported adaptations, is uneven by country, region, and sector, with distinct groups of leading nations evident. The top 20 nations reporting on adaptation all document over 14 adaptation initiatives, the top 10 over 30, combining a balance of groundwork and adaptation actions, and have responses directed to key vulnerabilities. These nations have been leaders consistently over the observation period. The bottom 20, however, all recorded 9 or fewer initiatives, with attention primarily directed toward groundwork. It is notable that leading adaptors were more likely to be low-income nations and be among nations ranking highly in adaptation financing received. A deficit in adaptation in lower and upper-middle-income nations is evident, albeit with key outliers including India and South Africa. Regional differences in reported adaptation also mirror trends in adaptation financing: sub-Saharan Africa, for instance, is the location of >50 % of the leading adaptors here and has received approximately 44 % of international adaptation finance (CFU 2012). Central Asia and North Africa have collectively received <10 % of such financing, reflected in the overall poor adaptation performance in these regions, and Asia 27 % (CFU 2012).

Geographical differences are consistent with the global dataset of adaptation of Berrang-Ford et al. (2011), with work examining adaptation in specific countries (Huq 2011; Mannke 2011; Sovacool et al. 2012a, b), and with other articles in this special edition (Lwasa, Sud et al.; Bizikova et al.) and indicates consolidation of adaptation leadership in key nations over time. The data suggest that international financing—through the World Bank and UNFCCC-mechanisms—plays a key role in moving adaptation onto the policy agenda, stimulating groundwork and adaptation actions by multiple levels of government, particularly for low and lower-middle-income countries. Bangladesh, for instance, has received the most adaptation funds in total ($191 m), performs highly here, and is regarded globally as a leader in responding to climate change, developing a long term adaptation strategy and investing proactively (Huq 2011). This is consistent with the general scholarship on adaptation in developing nations, which has argued that without external support, adaptation is typically a low priority (Fankhauser and Burton 2011; Huq et al. 2003; Kumamoto and Mills 2012). There are notable exceptions to this trend, however, and indicate that contextual factors also play a key role in stimulating adaptation: Pakistan, for example, has received the second largest amount of adaptation financing ($183 m) yet is in the bottom adaptors here, and underscores the need for further research to examine at a national and regional level factors driving adaptation (e.g., Lesnikowski et al. in press).

There are also a number of reasons for concern evident in what is not being reported. There is limited explicit recognition in reported actions of the need for transboundary adaptations, despite widespread acceptance that the risks posed by climate change cross-national boundaries (Kilroy in this special edition), or consideration of which adaptations are optimal across sectors. Adaptations may displace impacts both geographically and temporally, shifting vulnerabilities to other nations/regions, and potentially increasing vulnerability of the system as a whole (Adger et al. 2009), yet such ‘downstream’ effects are considered minimally. This is particularly pertinent for the Asian hotspot countries where a number of large rivers cross-multiple international boundaries (e.g., Ganges, Brahmaputra), and management of water resources is highly politicized and a source of conflict (see Sud et al. Bizikova et al. in this special edition). Melting glaciers and changing monsoonal patterns, coupled with population growth and economic development, are likely to place significant stress on water management in the future (IPCC 2014; World Bank 2010). Adaptation reporting by sector is also highly variable. While agriculture, and disaster and water management figure prominently in documented adaptations, and are among some of the key risks facing the hotspot nations, there is limited evidence of responses focusing explicitly on ecosystem management, coastal management, public health, or energy systems in reported adaptations. Varying by nation, climate change poses considerable risks to these sectors (IPCC 2014).

At the national level, adaptations remain predominantly at the groundwork stage, with limited progress beyond vulnerability assessments in many highly vulnerable countries and sectors. Many nations lack any NC, an updated NC, or national reporting beyond a handful of vulnerability studies. Substantive action to implement nationally coordinated adaptation initiatives in hotspot nations is negligible. The most advanced state of adaptation action, monitoring and evaluation of adaptation progress and outcomes, is absent here. Notably, NCs make limited reference to collaboration, networking, or cross-fertilization of adaptation actions occurring with the private sector, civil society, or at more local levels of government, and potentially indicates limitation strategic direction behind adaptations taking place. Finally, differing profiles of adaptation between literature types raise a number of important implications for sharing and cross-fertilization of adaptation lessons between sectors and scales. NCs are reporting initiatives almost exclusively at the national level, led by national governments, and related to adaptation policy. While this is expected given that NCs are national documents prepared to synthesize national programs of action on climate change, there is a notable absence of integration of sub-national adaptation action or links between national policy and more localized adaptation practice or civil society and the private sector. The peer-reviewed literature frequently reports on adaptation in practice at more local levels, while NCs contain negligible reference to activities occurring below the subregional level, indicating that national adaptation synthesis documents may not be informed by local level initiatives and adaptation lessons. These results paint a picture of national governments driving groundwork vulnerability assessments and policy, but not actively reporting on adaptation initiatives in practice occurring at local scales.

Similarly, adaptation in practice, as reported in the peer-reviewed and grey literature, does not necessarily reflect national priorities outlined in the NCs. This is particularly notable in the absence of reporting on public health adaptations. Importantly, the dichotomy here is not only one of scale (national vs. local) or literature type (NCs, grey, peer reviewed), but also of type (policy vs. practice). These results have implications for the creation and translation of adaptation policy into adaptation practice, with reporting on the former led by national governments and on the latter led by diverse agencies and institutions within diverse literature sources. Though we did not explicitly examine these trends, there appears limited indication in national documents of the extent to which national policies are informed by more local experiences and lessons. There is no comprehensive, systematic, and standardized literature source for reporting on sub-national adaptation policy. Similarly, it is unclear if national policy priorities are informing and translating into sub-national and local adaptations as reported in the peer-reviewed and grey literature. The relationship between adaptation policy and practice, with emphasis on who creates policy, where is adaptation practice taking place, and to what extent these activities are informing each other, would be a prudent focus of follow-up research arising from the results herein. In the meantime, the results suggest a need for enhancing cross-scale linkages between national planning and local initiatives. The UNFCCC has an important role herein: the NAP process for example, offers a venue for linking adaptation actors at different scales; web-based adaptation databases such as the UNFCCC’s Private Sector Initiative offer the potential to communicate adaptation actions and needs at different scales; the NC process could have a greater emphasis on profiling adaptations across scales, while ad hoc meetings held through the UNFCCC’s various committees offer the potential to bring together actors working on adaptation at different scales (e.g., 2014 joint meeting of the Adaptation Committee and Nairobi Workplan on the use of indigenous and traditional knowledge and practices for adaptation).

The different kinds of adaptation being reported by literature type have further implications for adaptation tracking research that seeks to systematically identify and characterize the current state of adaptation and monitor progress over time (Ford et al. 2013). Work in this field has used reporting on adaptation initiatives from single data sources as a proxy to characterize the state of adaptation, yet results from such research may be biased in the analysis of the kinds of adaptation being profiled. We therefore emphasize the importance of using multiple and diverse data sources in future adaptation tracking work. A key methodological challenge herein is how to integrate data from a proliferation of adaptation databases that have emerged in recent years to document and share information on adaptation actions. Such databases differ in reporting standards, detail provided, regional and sectoral focus, and systematization and rigor in data collection, yet nevertheless provide additional detail on adaptations taking place.

Conclusion

The importance of adaptation in climate policy is now widely recognized. With this, comes a need for researchers, practitioners, policy makers, donors, and governments to identify and characterize the state of policies, measures and strategies designed to reduce the burden of climate change impacts, both as a means of evaluating the effectiveness of adaptation support, informing governance at various levels on adaptation needs, and justifying funding allocation. In this paper, we inventory and analyze adaptation initiatives underway in 47 nations in Asia and Africa, using reporting in the peer-reviewed and grey literature, and policy documents, as our data source. The results offer preliminary insights on how adaptation is taking place at a general level, with other articles in this special edition providing more region and nation-specific insights including on the potential success of adaptations. A mixed picture of action is evident, in which the majority of nations report doing some adaptation. Adaptation leaders are clearly visible, with evidence of concrete action across sectors designed to reduce climate change vulnerability. Equally, for a number of nations highly vulnerable to climate change, there is little evidence of substantive adaptations taking place. For these adaptation laggards in particular, targeted research is needed to further investigate the status of adaptation to inform potential prioritization of future international adaptation financing.

References

Adger WN, Barnett J (2009) Four reasons for concern about adaptation to climate change. Environ Plan A 41:2800–2805. doi:10.1068/a42244

Adger WN, Eakin H, Winkels A (2009) Nested and teleconnected vulnerabilities to environmental change. Front Ecol Environ 7:150–157. doi:10.1890/070148

ATPSN (2011) Incidence of Indigenous and Innovative Climate Change Adaptation Practices for Smallholder Farmers’ Livelihood Security in Chikhwawa District, Southern Malawi. African Technology Policy Studies Network

Berrang-Ford L, Pearce T, Ford JD (2014) Systematic review approaches for global environmental change research. Reg Environ Change (this issue)

Berrang-Ford L, Ford JD, Patterson J (2011) Are we adapting to climate change? Glob Environ Change 21:25–33. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.09.012

Berrang-Ford L, Ford JD, Lesnikowski A, Poutiainen C, Barrera M, Berry P, Heymann J (2014) What drives national adaptation? Glob Assess Clim Change Lett 124(1–2):441–450. doi:10.1007/s10584-014-1078-3

Biagini B, Bierbaum R, Stults M, Dobardzic S, McNeeley SM (2014) A typology of adaptation actions: a global look at climate adaptation actions financed through the Global Environment Facility. Glob Environ Change 25:97–108. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.01.003

Biesbroek GR, Swart RJ, Cart er TR, Cowan C, Henrichs T, Mela H, Morcecroft MD, Rey D (2010) Europe adapts to climate change—comparing national adaptation strategies. Glob Environ Change 20:440–450. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.03.005

Biesbroek GR, Termeer C, Klostermann JEM, Kabat P (in press) Analytical lenses on barriers in the governance of climate change adaptation. Reg Environ Change. doi:10.1007/s11027-013-9457-z

Bizikova L, Parry J, Dekens J, Echeverria D (2014) Review of key initiatives and approaches to adaptation planning at the national level in semi-arid areas. Reg Environ Change. doi:10.1007/s10113-014-0710-0

Brooks N, Anderson S, Ayers J, Burton I, Tellam I (2011) Tracking adaptation and measuring development. Climate Change Working Paper No 1

CFU (2012) Climate funds update. http://www.climatefundsupdate.org/. Accessed May 2013

Costello A, Abbas M, Allen A, Ball S, Bell S, Bellamy R, Friel S, Groce N, Johnson A, Kett M, Lee M, Levy C, Maslin M, McCoy D, McGuire B, Montgomery H, Napier D, Pagel C, Patel J, Puppim de Oliveria JA, Redclift N, Rees H, Rogger D, Scott J, Stephenson J, Twigg J, Wolff J, Patterson C (2009) Managing the health effects of climate change. Lancet 373:1693–1733. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60935-1

De Souza K, Kituyi E, Leone M, Harvey B, Murali KS (2014) Vulnerability to climate change in three hot spots in Africa and Asia: key issues for policy-relevant adaptation and resilience-building research. Reg Environ Change (this issue)

Djoudi H, Brockhaus M (2011) Is adaptation to climate change gender neutral? Lessons from communities dependent on livestock and forests in northern Mali. Int Forestry Rev 13(2):123–135

Dupuis J, Biesbroek R (2013) Comparing apples and oranges: the dependent variable problem in comparing and evaluating climate change adaptation policies. Glob Environ Chang-Human Policy Dimens 23:1476–1487. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.07.022

Fankhauser S, Burton I (2011) Spending adaptation money wisely. Clim Policy 11:1037–1049. doi:10.1080/14693062.2011.582389

FAO (2011a) Lessons from the field: Madagascar—addressing disaster risk reduction on and adaptation on through local and improved rice seed production on in disaster prone areas. Food and Agriculture Organization to the United Nations

FAO (2011b) Lessons from the field: Bangladesh—coping with environmental stresses and climate change: towards livelihoods adaptation on for food security. Food and Agriculture Organization to the United Nations

Ford J, King D (in press) A framework for examining adaptation readiness. Mitig Adapt Strategies Glob Change. doi:10.1007/s11027-013-9505-8

Ford JD, Pearce T (2010) What we know, do not know, and need to know about climate change vulnerability in the western Canadian Arctic: a systematic literature review. Environ Res Lett 5. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/5/1/014008

Ford JD, Berrang-Ford L, Patterson J (2011) A systematic review of observed climate change adaptation in developed nations. Clim Change Lett. doi:10.1007/s10584-011-0045-5

Ford JD, Berrang-Ford L, Lesnikowski A, Barrera M, Heymann SJ (2013) How to track adaptation to climate change: a typology of approaches for national-level application. Ecol Soc 18. doi:10.5751/ES-05732-180340

Furgal CM, Garvin TD, Jardine CG (2010) Trends in the study of Aboriginal health risks in Canada. Int J Circumpolar Health 69:322–332

Gagnon-Lebrun F, Agrawala S (2007) Implementing adaptation in developed countries: an analysis of progress and trends. Clim Policy 7:392–408. doi:10.1080/14693062.2007.9685664

Gippner O, Dhakal S, Sovacool B (2012) Microhydro electrification and climate change adaptation in Nepal: socioeconomic lessons from the rural energy development program (REDP). Springer, Netherlands

GIZ (2011) Adaptation to climate change–Mozambique. The Deutsche Gesellschaft f r InternationaleZusammenarbeit (GIZ)

Hanger S, Pfenninger S, Dreyfus M, Patt A (2013) Knowledge and information needs of adaptation policy-makers: a European study. Reg Environ Change 13:91–101. doi:10.1007/s10113-012-0317-2

Huq S (2011) Lessons of climate change, stories of solutions. Bangladesh: adaptation. Bull At Sci 67:56–59. doi:10.1177/0096340210393925

Huq S, Rahman A, Konate M, Sokona Y, Reid H (2003) Mainstreaming adaptation to climate change in least developed countries (LDCS). International Institute for Environment and Development Climate Change Programme, p. 38

IIED (2010) Community champions: adapting to climate change challenges. International Institute for Environment and Development, UK

International C (2008) Tajikistan—designing adaptation strategies for vulnerable women. Gender perspectives: integrating disaster risk reduction into climate change adaptation: good practices and lessons learned. United Nations, international strategy for disaster reduction (UN/ISDR), pp 67–71

IOM (2009a) Migration, climate change and the environment. International Organization for Migration

IOM (2009b) Migration, climate change and the environment—environmental challenges and other intervening factors. International Organization for Migration, Geneva

IPCC (2007) Climate change: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Working Group II contribution to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change fourth assessment report, Geneva

IPCC (2014) Climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. In: IPCC fifth assessment report WGI (ed.)

Kilroy G (2014) A review of the biophysical impacts of climate change in three hotspot regions in Africa and Asia. Reg Environ Change. doi:10.1007/s10113-014-0709-6

Krysanova V, Dickens C, Timmerman J, Varela-Ortega C, Schlueter M, Roest K, Huntjens P, Jaspers F, Buiteveld H, Moreno E, Carrera JdP, Slamova R, Martinkova M, Blanco I, Esteve P, Pringle K, Pahl-Wostl C, Kabat P (2010) Cross-comparison of climate change adaptation strategies across large river basins in Europe, Africa and Asia. Water Resourc Manage 24:4121–4160. doi:10.1007/s11269-010-9650-8

Kumamoto M, Mills A (2012) What African countries perceive to be adaptation priorities: results from 20 countries in the Africa adaptation programme. Clim Dev 4:265–274. doi:10.1080/17565529.2012.733676

Lesnikowski AC, Ford JD, Berrang-Ford L, Paterson JA, Barrera M, Heymann SJ (2011) Adapting to health impacts of climate change: a study of UNFCCC Annex I parties. Environ Res Lett 6. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/6/4/044009

Lesnikowski AC, Ford JD, Berrang-Ford L, Barrera M, Berry P, Henderson J, Heymann SJ (2013) National-level factors affecting planned, public adaptation to health impacts of climate change. Global Environ Change Human Policy Dimens 23:1153–1163. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.04.008

Lesnikowski A, Ford JD, Berrang-Ford L, Barrera M, Heymann J (in press) How are we adapting to climate change? A systematic approach to measuring reported adaptation at the national level. Mitig Adapt Strategies Glob Change

Lorenz S, Berman R, Dixon J, Lebel S (2014) Time for a systematic review: a response to Bassett and Fogelman’s “Deja vu or something new? The adaptation concept in the climate change literature”. Geoforum 51:252–255. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.10.003

Mannke F (2010) An overview of community-based adaptation to climate change in Africa. The Arkleton Trust, p 144

Mannke F (2011) Key themes of local adaptation to climate change: lessons from mapping community-based initiatives in Africa. In: Leal Filho W (ed) Experiences of climate change adaptation in Africa, Springer, New York, pp 17–32

McDowell G, Stephenson E, Ford JD (in press) Adaptation to climate change in glaciated mountain regions. Clim Change

McLeman RA (2011) Settlement abandonment in the context of global environmental change. Global Environ Change Human Policy Dimens 21:S108–S120. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.08.004

O’Brien K (2012) Global environmental change II: from adaptation to deliberate transformation. Prog Hum Geogr 36. doi:10.1177/0309132511425767

Patt AG, Tadross M, Nussbaumer P, Asante K, Metzger M, Rafael J, Goujon A, Brundrit G (2010) Estimating least-developed countries’ vulnerability to climate-related extreme events over the next 50 years. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:1333–1337. doi:10.1073/pnas.0910253107

Poutiainen C, Berrang-Ford L, Ford J, Heymann J (2013) Civil society organizations and adaptation to the health effects of climate change in Canada. Public Health 127:403–409. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2013.02.004

Preston BL, Westaway RM, Yuen EJ (2011) Climate adaptation planning in practice: an evaluation of adaptation plans from three developed nations. Mitig Adapt Strat Glob Change 16:407–438. doi:10.1007/s11027-010-9270-x

RECCA (2011) Main climate change challenges for the water and agricultural sectors in central Asia on national level. Regional environmental center for Central Asia

Sherman MH, Ford J (2014) Stakeholder engagement in adaptation interventions: an evaluation of projects in developing nations. Clim Policy 14:417–441. doi:10.1080/14693062.2014.859501

Smith B, Burton B, Klein RJT, Wandel J (2000) An anatomy of adaptation to climate change and variability. Clim Change 45:223–251. doi:10.1023/A:1005661622966

Sovacool BK (2012) Expert views of climate change adaptation in the Maldives. Clim Change 114:295–300. doi:10.1007/s10584-011-0392-2

Sovacool BK, D’Agostino AL, Meenawat H, Rawlani A (2012a) Expert views of climate change adaptation in least developed Asia. J Environ Manage 97:78–88. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2011.11.005

Sovacool BK, D’Agostino AL, Rawlani A, Meenawat H (2012b) Improving climate change adaptation in least developed Asia. Environ Sci Policy 21:112–125. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2012.04.009

Stucker D, Kazbekov J, Yakubov M, Wegerich K (2012) Climate change in a small transboundary tributary of the Syr Darya calls for effective cooperation and adaptation. Mt Res Dev 32:275–285. doi:10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-11-00127.1

Sud R, Mishra A, Varma N, Bhadwal S (2014) Adaptation policy and practice in densely populated glacier-fed river basins of South Asia: a systematic review. Reg Environ Change. doi:10.1007/s10113-014-0711-z

Surminski S (2013) Private sector adaptation to climate risk. Nat Clim Change 3(11):943–945

Townshend T, Fankhauser S, Aybar R, Collins M, Landesman T, Nachmany M, Pavese C (2013) How national legislation can help to solve climate change. Nat Clim Change 3:430–432

UNEP (2011) Technologies for climate change adaptation: agricultural sector—Afghanistan. United Nations Environment Program

WFP (2011) Building resilience: bridging food security, climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction—Afghanistan. World food programme office for climate change and disaster risk reduction

World Bank (2008) Climate change adaptation in Europe and Central Asia: disaster risk management. World Bank, Washington

World Bank (2010) World development report—development and climate change. World Development Report, Washington

World Bank (2011) Climate-Smart Agriculture: increased productivity and food security, enhanced resilience and reduced carbon emissions for sustainable development—Uzbekistan

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the CARIAA program of the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and the UK Department for International Development (DFID). Thanks to two anonymous reviewers who provided detailed and constructive feedback.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ford, J.D., Berrang-Ford, L., Bunce, A. et al. The status of climate change adaptation in Africa and Asia. Reg Environ Change 15, 801–814 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-014-0648-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-014-0648-2