Abstract

To understand how climate adaptation planning and decision-making will progress, a better understanding is needed as to which organisations are expected to take on key responsibilities. Methodological challenges have impeded efforts to identify and track adaptation actors beyond the coarse scale of nation states. Yet, for effective adaptation to succeed, who do national governments need to engage, support and encourage? Using the UK as a case study, we conducted a systematic review of official government documents on climate adaptation, between 2006 and 2015, to understand which organisations are identified as key to future adaptation efforts and tracked the extent to which these organisations changed over time. Our unique longitudinal dataset found a very large number of organisations (n = 568). These organisations varied in size (small-medium enterprises to large multinationals), type (public, private and not-for-profit), sector (e.g. water, energy, transport and health), scale (local, national and international), and roles and responsibilities (policymaking, decision-making, knowledge production, retail). Importantly, our findings reveal a mismatch between official government policies that repeatedly call on private organisations to drive adaptation, on the one hand, and a clear dominance of the public sector on the other hand. Yet, the capacity of organisations to fulfil the roles and responsibilities assigned to them, particularly in the public sector, is diminishing. Unless addressed, climate adaptation actions could be assigned to those either unable, or unwilling, to implement them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

If mitigation alone cannot reverse the risks posed by climate change, attention rightly shifts to how to help communities, businesses and governments prepare for, and adapt to, the unavoidable impacts to come. Such thinking is embodied in the 2015 Paris Accord’s global goal on adaptation. Since its signing, a considerable level of resources, both public and private, has been directed towards enhancing adaptive capacities, strengthening resilience and reducing vulnerabilities to climate change (UNFCCC 2016: Article 7). But, as Christiansen et al. (2018) explain, it is not always clear how well these efforts have translated into a more resilient and less vulnerable society or where future efforts are needed.

Disagreements over what exactly constitutes ‘successful’ or ‘effective’ adaptation (Dupuis and Biesbroek 2013; Ford et al. 2013), inconsistencies in the availability and reliability of metrics for measuring progress (Ford et al. 2015; Ford and Berrang-Ford 2016; Kamperman and Biesbroek 2017), and difficulties in assessing whether those assigned adaptation roles/responsibilities are able, and willing, to act (Eisenack and Stecker 2012; Porter et al. 2015), reveal the complex, contested and messy nature of adaptation in practice. Adaptation research’s preference for single, or small-n case studies, only adds further problems (Swart et al. 2014). Such studies, whilst helpful in explaining why adaptation is contingent upon wider socio-technical and institutional-political considerations, can also limit the identification of lessons across different regions, sectors and contexts (Dupuis and Biesbroek 2013). Adaptation tracking has emerged in response. Put simply, it champions the use of a systematic and standardised criteria from which adaptation can be evaluated and compared over time as well as across regions/sectors (Ford et al. 2013, 2015; Christiansen et al. 2018). As a result, documenting adaptation progress, prioritising funding for areas of greatest concern and identifying where governance gaps exist can now be performed more effectively, transparently and accountably.

Lesnikowski et al. (2016), for instance, used adaptation tracking to compare the progress made by different countries via an analysis of National Communications submissions to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). In doing so, different levels of commitment, and different capacities to adapt, were identified across the world. Only eight countries achieved the highest ‘global leader’ status: Australia, Canada, Finland, Portugal, Norway, Sweden, Spain and the United Kingdom (UK). Putting aside the widely held, if not critiqued, perception that adaptation is primarily a local process (Preston et al. 2014; Atteridge and Remling 2018), such global analyses emphasise the need to understand why some countries are progressing on adaptation better than others. This focus on national governments is understandable, as the Stern Review (2006) argues, because they are responsible for (1) protecting those least able to adapt by addressing the causes of their vulnerability, (2) providing information and resources to help plan and stimulate adaptation and (3) offering protection to public goods including air quality, ecosystems and flood defences (Stern 2006).

But as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) latest assessment report explains, progress on adaptation depends heavily on the involvement of two other actors: local government and the private sector (Noble et al. 2014: p. 836). ‘These two groups [will] bear responsibility for translating the top-down flow of risk information and financing and in scaling up bottom-up efforts of communities and households in planning and implementing their selected adaptation actions’ (ibid). Despite efforts from national governments to get private businesses, local government and civil society to engage with the risks and opportunities posed by climate change, and in turn, offer them support to plan and adapt, adaptation remains heavily dominated by central government initiatives and it is unclear to what extent these have effectively translated into local government action (cf. Tompkins et al. 2010). This is concerning because as Green et al. (2018) have found, it is crucial to involve a wide diversity of actors with different issues, from different sectors, working across different scales, to ensure different values, interests and concerns are represented in efforts to tackle climate change. How to do this is not always clear. Much debate persists over when and where different actors should be introduced into the adaptation process or even which actors are key (Biesbroek et al. 2011; Tompkins and Eakin 2012; Juhola 2013; Klein et al. 2017).

For Berkhout (2012: p. 91), ‘organisations [are] the primary actors involved in choosing and enacting societal responses to climate change’. Organisations, in this case, are collectives of actors whose activities are coordinated within discrete social conditions to achieve common goals. These include private businesses, public organisations (e.g. central/local governments), charities and civil society. Whether climate change, or adaptation more specifically, steers organisational behaviour depends on the extent to which it compliments existing strategic goals. These goals range widely from profit seeking to more socially responsive aspirations around education, healthcare and welfare (Berkhout 2012). Likewise, organisations have different structures, cultures and capabilities to help achieve their goals (Willows and Connell 2003; Arnell and Delaney 2006; Berkhout et al. 2006; Hoffman et al. 2009; Green et al. 2018). Such realities remind us that economic thinking alone rarely guarantees action. As Berkhout (2012: p. 92) put it, ‘even in organisations, like farming businesses, that appear highly exposed to climate variability, responses to climate change will always compete as a priority with other strategic or operational concerns’.

Given that the UK is considered to be a global leader on adaptation (Lesnikowski et al. 2016), we aim to shed light on which organisations and sectors are seen to be key adaptation actors by the UK government. Using a unique longitudinal dataset, presented here for the first time, we conducted a systematic review of UK official government documents on climate adaptation, published between 2006 and 2015, to identify which organisations are seen as key to future adaptation efforts and track the extent to which the pattern of organisations identified in these documents changes over time. Before explaining our data and method, we provide a brief overview of the UK’s adaptation context and the roles and responsibilities of key organisations. Following on, our results examine which organisations are most frequently cited within official documents and how these organisations vary in type and sector. Building on this, we explore how the pattern of organisations identified in the reports changes over a 10-year period, as different government administrations have come and gone, and whether the capacity exists for these organisations to adapt. To close, we will examine to what extent the current UK government rhetoric on adaptation as championed through its National Adaptation Plans matches the reality of those actors advocated by the government to progress adaptation and call attention to what happens when climate adaptation roles/responsibilities are centred only on a few actors.

Context: Climate change adaptation in the UK

Since the UK Climate Change Act was passed in 2008, the administrative roles/responsibilities for climate change have been divided between (1) mitigation policies (e.g. greenhouse gas emission reductions, renewable technology initiatives) set by the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC)Footnote 1 and (2) adaptation policies (e.g. flood management, nature conservation) set by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). Under the Act, the Secretary of State for Environment can direct organisations responsible for critical infrastructure, utilities and transport networks to report on how they plan to tackle climate risks.

To help the government identify which organisations should be part of this Adaptation Reporting Powers exercise, the Climate Change Act requires a national climate change risk assessment (CCRA) to be conducted every 5 years to rank the severity of different risks and the vulnerability of different sectors (Defra 2012). On top of this, the government is required to issue a National Adaptation Plan (NAP) setting out how these risks will be addressed (Defra 2013: p. 4). A major objective of this plan is to foster ‘a society which makes timely, far-sighted and well-informed decisions to address the risks and opportunities posed by a changing climate’ (ibid). Emphasis here is very much on recognising the limits to what government interventions can do. Official government policy makes it clear that the ‘government cannot act alone’ (Defra 2013: p. 1). Local governments, industry and civil society must take on new climate adaptation responsibilities, as they ‘know what works best in their sectors’ (ibid). To scrutinise the progression made on adaptation, the Committee on Climate Change was set up with its Adaptation Sub-Committee reporting directly to Parliament. As Massey and Huitema (2013, 2016) explain, these institutional-political conditions have led to the unique situation of climate adaptation becoming a policy field in its own right in the UK.

To help inform adaptation planning and decision-making, the UK’s Met Office provides climate information to government departments, through contracts with DECC and Defra, and also releases free-to-use climate projections (Jenkins et al. 2009). To improve the uptake and use of this information, the UK Climate Impacts Programme (UKCIP) was set up in 1997. Working at the interface of climate science and decision-making, UKCIP raises awareness of, and provides practical advice on, how to adapt to climate impacts for different stakeholders (Hedger et al. 2006). In 2011, UKCIP’s official responsibilities were transferred to a new Climate Ready team in the Environment Agency (Salvidge 2016). Already responsible for managing flood risk, water resources and ecosystems, the Environment Agency is a non-governmental public body tasked with operationalising Defra’s environmental policies.

Given this considerable institutional-legislative apparatus, it is not surprising that the UK’s approach to adaptation has largely been considered to be top-down (Tompkins et al. 2010). In 2004/2005, Tompkins et al. (2010) collected and analysed documentary evidence from official sources covering 300 examples of climate adaptation. They found that although public and private organisations were beginning to make small adjustments and develop their adaptive capacities, observed adaptation was still largely driven by national government initiatives. Since 2010, successive UK governments have tried to reverse this trend. First, the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government, followed by the Conservative government from 2015. In 2013, the publication of the UK’s first NAP shifted responsibility for adaptation away from the state and onto non-state actors stating that ‘if adapting to climate change is in the private interests of an individual and an organisation then it should occur naturally and without the government’s intervention’ (Defra 2013: p. 7). In this study, we will aim to assess whether this rhetorical shift towards more of a bottom-up approach to adaptation is mirrored in the organisations that central government focuses on through the documents it published on adaptation between 2006 and 2015.

Data and methods

How to sample adapting UK organisations?

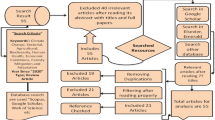

To understand which organisations have been officially ascribed roles and responsibilities for climate change adaptation in the UK, and to examine the extent to which attention received by these organisations has changed over the last decade (2006–2015), we conducted a systematic review of official documents prepared for, or commissioned by, the UK government in relation to climate change adaptation. These documents included policies, plans, reports, assessments and strategies. As matters of public record, these documents provide the official grounds through which the UK government explains how adaptation risks and opportunities should be managed, and most importantly, by whom. To that end, we adopted the definition that planned adaptation is the ‘result of a deliberate policy decision, based on an awareness that conditions have changed or are about to change and that action is required to return to, maintain or achieve a desired state’ (Parry et al. 2007: p. 869).

Following Turnpenny et al. (2005), we sourced documents from UK government websites. Keyword searches were performed using phrases such as ‘climate change adaptation’, ‘adaptation’ and ‘adaptation plan’. During the data collection process, all government documents were in the process of being migrated from individual departmental websites to a central repository: gov.uk. However, as this process was incomplete in October 2015, when we collected the data, we also conducted searches within old websites such as Defra, the Committee on Climate Change, the Met Office Hadley Centre, UKCIP and the Water Services Regulation Authority (Ofwat) webpages (see Online Supplementary Material 1 for a full list of searched websites and search terms). One hundred forty-six original documents were returned as well as 27 supplementary documents pertaining to them (total n = 173). These 173 documents were downloaded into a qualitative data software tool: NVivo (see Online Supplementary Material 2 for a full list of the 173 documents).

How to identify UK adaptation organisations?

Our analysis centred on official documents that discussed current and future UK adaptation actions, roles and responsibilities, and therein, named organisations that are or should be involved. To identify these organisations, we read the executive summaries, introductions and conclusions of the 146 original documents found through our government webpage search and ranked them on a 5 point Likert Scale to indicate the extent to which the text primarily discussed the roles/responsibilities of adaptation organisations (1, not at all relevant; 2, slightly relevant; 3, moderately relevant; 4, very relevant; 5, extremely relevant) (see Online Supplementary Material 3 for the full list of ranked original documents). Documents received a low ranking if they only provided scientific, economic or risk assessments of the impacts of climate change in the UK. For instance, the lowest ranking of 1 was given to the PricewaterhouseCoopers report: ‘International Threats and Opportunities of climate change for the UK’, as it focused on mapping the risks faced by different UK sectors, not the specific organisations per se. Whereas the highest ranking of 5 was awarded to the AEA Technology Report: ‘Adapting the ICT sector to the impacts of climate change’ because it differentiated between the urgent actions needed from various actors (e.g. central government, ICT providers, researchers). Whilst all these documents increase our understanding of how the UK may be affected by climate change, and detail what options could be explored, these same documents do not always identify which organisations are or should be involved in that process.

Approximately a third of the documents achieved a ranking of 3 or above (n = 50/146). This subset was examined further to extract specific named organisations including government departments, private businesses, trade associations, regulators and community groups, amongst many others. This more detailed reading resulted in 568 actors being identified (see Online Supplementary Material 4 for a complete list of actors). It is important to note that organisations referenced in the documents can be attributed different capacities, such as information providers, data sources, implementation partners, funders for action or regulators. For example, the UK’s first NAP designated Defra with three interrelated roles: implementer of actions, policy developer and information provider. For this analysis, we do not distinguish between these different capacities, but treat them equally, as our aim is to capture the overarching landscape of organisations involved, which span a wide variety of capacities, roles and responsibilities.

How to code the UK adaptation organisations identified?

To characterise these organisations, and better understand any underlying trends, we introduced two levels of classification. First, we coded each organisation according to its funding model into public, private or not-for-profit (third sector). We then subdivided the public sector into central, local and other. Second, following Tompkins et al. (2010), we categorised the primary activities of these organisations. Organisations were coded using the following sectors: (i) agriculture; (ii) art, culture, media and sport; (iii) business; (iv) central government; (v) charity; (vi) civil society; (vii) communications; (viii) conservation and environment; (ix) construction; (x) education; (xi) emergency; (xii) energy; (xiii) finance; (xiv) health; (xv) insurance; (xvi) local government; (xvii) retail; (xviii) scientific and technical advisory services; (xix) security; (xx) tourism; (xxi) transport; (xxii) water and (xxiii) other (see Online Supplementary Material 5 for a list of sectors and descriptions).

Local government and central government were included in both sector and type categorisations. The rationale behind this being that some organisations have responsibilities that are cross-cutting instead of sector-specific at the local or central level. Therefore, Parliament, Cabinet Office, Her Majesty’s Government, Cabinet Office Briefing Room and the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, were assigned the ‘central government’ type and sector and all Local Authorities and Public Local Associations such as Local Climate Change Partnerships were assigned the ‘local government’ type and sector.

To acknowledge the ambiguities that can arise in any coding exercise, a random sample of organisations (n = 57, ~ 10% of the total) were coded independently by two of the authors and intercoder reliability tests were performed showing moderate-substantial agreement between the two coders (type: K = .590, p < .001, sector K = .711, p < .001). These scores achieved an acceptable standard of intercoder reliability (Landis and Koch 1977).

How were the documents analysed?

To ascertain which organisations are expected to play the most prominent role in climate change adaptation, we used the NVivo query function and systematically searched all 173 documents for mentions of the 568 organisations (including acronyms and alternative wordings). To avoid the risk of double counting, all searches were checked and cleaned manually to exclude organisations named in the header/footer of the documents.

To determine the top 10% of organisations of greatest importance, we firstly ranked all organisations based on the number of references made to each organisation across the 173 documents returned through the coding (total frequency) and then ranked them based on the number of documents that referred to each organisation (total documents). Recognising that some organisations may be mentioned numerous times within the same documents, and that thus the number of documents within which an organisation is cited, is a more accurate proxy as to how relevant an organisation is considered to be for adaptation, we applied a weighting factor to both rankings. Based on this, we applied a weighting factor of 0.67 to ‘total documents’ and a weighting factor of 0.33 to ‘total frequency’. The mean rank of organisations was then calculated from the weighted ranks and the top 10% of organisations were extracted.

What are the limitations of the data?

Introducing a new method, inevitably, encounters challenges. The units of analysis were one such challenge. What counts as ‘adaptation’ in official climate change documents reviewed? Following Tompkins et al.’s (2018) approach, we provided a comprehensive documentation of all organisations mentioned in the documents analysed instead of judging whether to include them or not based on evaluating their adaptation actions. Identifying organisations per se does not equate to actions taken. However, our aim here is to map the composition of the UK’s adaptation actor landscape. “Results” and “Discussion and conclusion” provide insights as to whether those organisations can take meaningful action.

A more detailed matrix that ranks the relevance of organisations as well as reflects the types of organisations and number of actions they have taken would be beneficial in future. Nevertheless, our findings, outlined in “Results”, provide a strong contribution to Tompkins et al.’s (2018) proposal of a more coordinated stocktaking approach for adaptation actions that (1) establishes consensus of adaptation objectives, (2) agrees sources of evidence, (3) agrees search methods and (4) categorises adaptations.

Another challenge is that organisational remits can span several sectors. We decided to categorise organisations according to their primary sector, but future studies that apply multiple categorisations would be relevant for a multi-layered sectoral analysis. For this study, assigning a single sector offers an important first step in exploring how the UK’s adaptation landscape is structured, which can be refined for future studies as trends emerge.

Focusing on documents that were published or commissioned by central government also arguably provides only one method for understanding the overall adaptation landscape. That said, as Tompkins et al. (2010) have found, the UK’s top-down approach to adaptation—where the 2008 Climate Change Act assigns legal duties that the government must perform—means that the UK government plays a vital role in proposing, funding, supporting and overseeing adaptation actions, and in turn, linking networks, partnerships and organisations together. As a result, how the UK government makes sense of the adaptation landscape, and by extension, who it ascribes roles/responsibilities to, provides a crucial lens through which to critically examine whether the rhetoric calling for a more bottom-up approach to adaptation has become a reality.

Results

Which organisations were officially assigned key roles or responsibilities for UK climate change adaptation?

In total, our review identified 568 distinct organisations that official documents suggest play a key role in, or have responsibilities in relation to, adaptation to climate change. These organisations varied considerably. We found different sized organisations (e.g. from small or medium enterprises to large multinationals), different organisational types (i.e. public, private and third sector), organisations that work within different sectors (e.g. water, agriculture, energy, transport and health), across different scales (i.e. local, regional, national and international) and organisations tasked with different core roles and/or responsibilities (e.g. policymaking, decision-making, knowledge production or retail products/services).

At first glance, the diversity of organisations suggests that the UK government understands that adaptation should not be the exclusive preserve of a select few—who either have the capacity or inclination to tackle it—and instead should engage, and most importantly support, the inclusion of as many different organisations as possible. Such diversity is encouraging. It enables multiple (and divergent) adaptation strategies to be explored to avoid being locked into a single approach that, if it fails, could have far-reaching consequences (Smit et al. 1999). Yet when we categorised these organisations further, according to type and sector, a more homogenous picture emerged.

Of the 568 organisations, the majority were publicly owned or operated (n = 297, 52.3%). Within the public organisations, approximately a quarter (n = 73, 24.6%) are from central government and local government (n = 66, 22.2%) respectively, and just over half fall in the ‘other’ category (n = 158, 53.2%). The remainder of the organisations are relatively evenly split between privately run organisations (n = 143, 25.2%) and third sector organisations (n = 128, 22.5%). On the one hand, this suggests that the UK government’s efforts to help mainstream adaptation and encourage a more bottom-up approach where organisations beyond the state take over responsibility for adaptation planning and implementation may be bedding in. On the other hand, private organisations still only account for about a quarter of the overall total named organisations. One reason for this could be due to the purpose of official documents and practical limits on them. Listing every organisation that has a role or responsibility regarding climate change adaptation not only runs the risk of a lengthy who’s who of the UK but also reduces the readability of the document.

Of interest here is that nearly a quarter (n = 128, 22.5%) of all organisations were from the third sector including trade associations, trade bodies or professional networks. These already have systems in place to reach a large audience on behalf of the UK government and tailor the message for them. Those frequently cited included the National Farmers Union, the Association of British Insurers and Energy Network Providers, who collectively represent thousands of individuals and organisations.

A different pattern emerged, however, when we look at the top 10% of organisations cited (see Table 1). Most organisations were publicly owned or run (n = 47, 82.5%) with a much smaller number from the private (n = 2, 3.5%) or third sector (n = 8, 14.0%). It thus seems as if the rhetoric, encouraging more bottom-up adaptation by private actors and organisations, set out by the first UK NAP 2013 is not reflected in the documents published by the government. This is particularly noteworthy as it relates to whom the UK government sees as the most significant adaptation organisations, and importantly, points to a disconnect between recent rhetoric and the inherent inertia of past actions.

Of the 47 public organisations cited in the top 10% of organisations, by far, the main group was central government (n = 36, 76.6%). Within this subset, we find that government agencies (n = 19, 40.4%), including the Environment Agency, the NHS, and Highways Agency as well as Her Majesty’s Government Ministries and Departments (n = 14, 29.8%) such as Defra, the Department for Communities and Local Government, and Department of Transport, occupy the top two groupings. This high proportion of central government organisations means adaptation responsibilities are spread across government departments, all of which have different remits, resources and commitments to adaptation. This can make a coherent and coordinated approach challenging. Despite the emphasis on the need for local level adaptation, Local Government organisations only comprise a small percentage of key actors (n = 5, 10.9%).

If we focus on the top 5 organisations cited most often, a broad mix of remits is found from national/local policy, planning and implementation (e.g. Defra, Environment Agency, Local Authorities, Parliament), to efforts to raise awareness of climate change and improve decision-making (e.g. UKCIP). No private organisations made it into the top 10. This could be because sectors such as water in England operate regionally, not nationally, or the high number of competitors in sectors including energy, which naturally limit the dominance of a single organisation. That said, the highest ranked private organisation was Network Rail (rank 26), responsible for the UK’s railway infrastructure, followed by the National Grid (rank 40), responsible for the UK’s electricity and gas network.

Two points are worth flagging up here. First, the two private organisations in the top 10% of organisations come from the following two sectors: energy and transport, whilst other major sectors dominated by private entities including food, retail and finance are absent. Second, whilst adaptation to climate change is legislated nationally, we find a clear geographical imbalance and a very England-centric focus—no organisations in the top 10% are based in any of the devolved administrations: Wales, Northern Ireland or Scotland.

The dominance of central government organisations drops away when we code and rank all 568 organisations by their primary sector instead of by their type. In the place of the central government, we find that local government (n = 69, 12.1%) becomes the dominant sector, spanning councils, resilience forums and local government networks. This affirms the crucial role played by local level planning and decision-making in adaptation (Porter et al. 2015). The second highest ranked sector was transport (n = 65, 11.4%), covering roads, rails, planes and boats. Again, this supports findings from other studies that place transport at the centre of adaptation activities (see Eisenack and Stecker 2012; Walker et al. 2015). The third biggest sector was education and research (n = 61, 10.7%) comprising of universities, research institutions and programmes, with the energy (n = 56, 9.9%), conservation and environment (n = 43, 7.6%), and water (n = 38, 6.7%) sectors ranked fourth, fifth and sixth respectively.

Out of the 568 organisations identified, only a small number belong to the finance (n = 20, 3.5%), business (n = 16, 2.8%) or the agricultural (n = 8, 1.4%) sectors. Both the UK’s first CCRA and the economic assessment behind the NAP highlighted the serious risks posed by climate change to food security and future trade (HR Wallingford 2012; PricewaterhouseCoopers 2013). It was found that the international risks posed by climate change to the UK could be ‘an order of magnitude larger than domestic threats and opportunities’ particularly for ‘business (trade/investment) and food (supply chains)’ (PricewaterhouseCoopers 2013: p. 2). Not only does this point to a lack of awareness over who is a relevant adaptation organisation in these sectors but also raises questions about whether these sectors have the capacity to cope with future stresses.

Another sector ranked lowly was communications (n = 9, 1.6%), populated by telephone, broadband and internet providers. Given the increasing reliance of other sectors on telecommunications, due in part to the growth of digitised operations, our review helps identify the problem of treating sectors as discrete, self-contained, entities. Sectors rarely act alone. Rather they are reliant, sometimes unknowingly, on (invisible) interactions with others. Low levels of awareness of how different sectors are connected to one another, or are needed to help others function properly, could lead to a domino effect where risks in one sector cascade through the system to bring about widespread failures (Committee on Climate Change 2017).

To what extent has the pattern of organisations identified in official documents changed from 2006–2015?

Between 2006 and 2015, the UK experienced considerable political change. Three different governments were elected, new legislation dedicated to tackling climate change was introduced and austerity measures were implemented across public services. That withstanding, we found the same organisations were cited repeatedly each year by official climate change adaptation documents. Yet the frequency, and order, of these organisations within the top 10% did change as did the number of adaptation documents published year-on-year.

Figure 1 tracks the number of official climate adaptation documents published each year and reveals two key trends. First, almost half of all official documents written between 2006 and 2015 were clustered into only two consecutive years, 2010 and 2011 (n = 78, 45%). Second, after 2011, we see a distinct decline again in the overall number of adaptation documents. By 2015, the number of climate change adaptation publications has shrunk by 71% since 2010, dropping below the 2006 baseline (2015: n = 13, 2006: n = 14). Several political changes track these developments. In mid-2010, the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government came to power, after the Labour government lost the general election, which was followed in 2015 by a Conservative government. Furthermore, two adaptation landmarks introduced by the Climate Change Act 2008—the UK’s first CCRA in 2012 and NAP in 2013—were unable to create as much of a drive towards adaptation as can be seen through the much larger numbers in adaptation publications of earlier years.

Of course, the number of official climate change adaptation documents issued every year should not be confused with progress on planning and implementing actions but the overall decline in numbers, as shown in Fig. 1, suggests that adaptation is no longer receiving the same level of policy support and attention. For instance, in 2013 Defra, who are responsible for the UK climate change adaptation policy cut adaptation funding by nearly 40% (from £13.65 million in 2011/2012 to £8.31 million in 2013/14) (Defra 2014), and Defra officials working on adaptation were cut from 38 to 6 (Harvey 2013).

To understand how the distribution of key organisations cited in official climate adaptation documents has changed between 2006 and 2015, we introduced four distinct timeframes: (i) quarter 1, from January 2006 to June 2008, (ii) quarter 2, from July 2008 to December 2010, (iii) quarter 3, from January 2011 to June 2013 and (iv) quarter 4, from July 2013 to October 2015 (Fig. 2).

Distribution of top 10% of organisations by sector per quarter, 2006–2015. For ease of graph readability, only sectors with organisations that reached 3% or more were depicted (for a full breakdown of sectors by quarter, please see Online Supplementary Material 6)

Turning first to the composition of all 568 organisations by sector, we calculated how the percentage of each sector changed according to how many organisations were mentioned in that quarter. We found that, regardless of the ebbs and flows in the number of adaptation publications per quarter, four sectors were repeatedly in the top five: transport, energy, conservation and environment, and education and research, if not in a slightly different order each time. Local Government was also prominent in three of the four quarters, only to be replaced by the water sector in the final quarter. Likewise, the bottom five sectors always included art, culture, media and sport, and insurance, and in three out of four quarters, tourism and security. We find similarities for the top 10% of organisations with conservation and environment, and transport in the top 5 consistently, and local government in a prominent first or second position in three of the four quarters. The retail, tourism, charity and arts, culture, media and sports sectors were not present in the top 10% in any of the quarters, and the emergency, security and communications sectors were absent in three of the four quarters.

The lack of inter-variability of organisations by sectors in each quarter, and across the decade, may suggest on the one hand that awareness of what adaptation work is needed, and most importantly, by whom, is well ingrained within UK government thinking. On the other hand, this may also suggest that the UK government is either unaware of the key role and responsibilities that less well-cited sectors can play in adaptation or that persistent barriers exist that prevent them from being fully engaged. This is underlined by the fact that some sectors that are extremely relevant to both planning for adaptation and extreme events as well as responding to them seem to be entirely disengaged. The insurance sector, for example is represented by less than 1% of organisations in each quarter and the share of the communications and emergency sectors both shrank by 32% by 2013–2015 compared with 2006–2008.

When we focus on the top 10 organisations cited per quarter, as shown in Table 2, we find that organisations with the same core roles and/or responsibilities consistently appeared: national and local policymakers, planners and implementers (e.g. Defra, Local Authorities), government agencies (i.e. Environment Agency), legislators (i.e. parliament) and those tasked with raising awareness and offering decision support on climate change (e.g. UKCIP). Of these, there is very little change in the top 5, with Defra always ranked first, the Environment Agency always ranked second or third and Local Authorities ranked between second and fourth. UKCIPFootnote 2 also ranked third, fourth and sixth in the first three quarters. Together, these four actors account for 38%, of all references across the decade. Interestingly, in the final quarter, 2013–2015, the National Health Service and Public Health England jumped up the list. The reason for this is due, in part, to 6 of the 13 documents published that quarter, focusing on climate change impacts and health.

Our results suggest that the attention given to sectors can quickly increase when sufficient political support exists. Yet, key sectors not only remain absent (e.g. retail and tourism) or largely absent (e.g. security, communications, finance and emergency) but also the gap between them and the more established adaptation sectors remains as large as before.

No private organisation featured in the top 10 between 2006 and 2015. The closest was the consultancy HR Wallingford (which led the development of the UK’s first CCRA) ranked 23rd in the third quarter, 2011–2013, followed by the train operator Network Rail ranked 31st and 26th in the second (2008–2010) and fourth (2013–2015) quarter respectively. As a result, the top 10 is occupied almost exclusively by public organisations, with the only exception being civil society appearing in seventh place in the third quarter (2011–2013).

Discussion and conclusion

We find that official climate change adaptation documents show that the UK Government is aware of, and committed to, engaging as diverse a mix of adaptation actors as possible. Different types/sizes of organisations, working within different sectors, across different scales, and performing different roles and/or responsibilities, are all identified. Such diversity ensures that different values, interests and concerns are represented (Green et al. 2018). Yet, despite the UK government clearly calling for a more bottom-up approach to adaptation in its NAP, we found little evidence that this rhetoric is consistently reflected in the documents the government has published on adaptation between 2006 and 2015.

For instance, adaptation roles and/or responsibilities were two times more likely to be assigned to public than private organisations, and slightly more likely to focus on central government compared with local government actors. On the one hand, this suggests that the UK Government recognises that for adaptation to be effective it must be integrated into every governance level of the policies/services it provides. Yet, it can be risky to expect central and/or local government to spearhead adaptation efforts when these actors are sensitive to political agendas. Indeed, from 2006 to 2015, we have witnessed several substantial changes affecting the key actors identified in the documents. Climate change funding from the government was cut. Not only did this affect Defra but it also led to UKCIP’s responsibilities being initially transferred to the Environment Agency’s Climate Ready team, which itself has now been closed with no replacement planned (Salvidge 2016). In addition, since 2010, Local Government spending has been cut by 40% (Hastings et al. 2015) leading to staff redundancies and adaptation being deprioritised to safeguard frontline services (Fitzgerald and Lupton 2015; Porter et al. 2015; Lorenz et al. 2017). Furthermore, the institutional arrangements for mitigation and adaptation have been revised (e.g. DECC), as well as climate reporting requirements relaxed (e.g. ARP). With government departments, agencies and public bodies shouldering the majority of adaptation roles and/or responsibilities, questions remain about ‘who’ will step in if central and/or local government do not have the institutional capacity or political will to adapt and make meaningful changes (cf. Porter et al. 2015).

By identifying which organisations national governments deem essential to ensuring their country is well adapted, and the extent to which the pattern of organisations and sectors changes over time, we are able to assess what is working well and where more attention is needed. In the case of the UK, infrastructural systems, which are crucial to the resilience and robustness of energy, and transport services, are all highly cited. Yet, some individual sectors, including finance and telecommunications, are largely absent from official climate change adaptation documents. No mentions are made of the finance sector in the last quarter of the decade analysed. This is a little surprising given the finance sector contributed £119 billion to the UK economy in 2017 (6.5% of total economic output) (Rhodes 2018). In turn, the interdependency of risks shared across sectors is also concerning. When Storm Desmond hit the UK in 2017, ‘failures of electricity and telecommunications networks, and bridges, quickly and unpredictably affect[ed] other services, heightening disruption and hampering the efforts of emergency services’ (Committee on Climate Change 2017: p. 17). A lack of awareness, or willingness, to address climate risks in one sector can cascade through the entire system, putting everyone at risk.

Our research shows that identifying and tracking key adaptation actors is a useful first step in understanding the political commitment of national governments to tackle climate change, (cf. Lesnikowski et al. 2013; Ford et al. 2015). However, our research also highlights that rhetoric and reality are not the same. In the case of the UK, the call for a more bottom-up approach to adaptation is not reflected in the types of organisations named by central government publications. Whilst documents published by the UK government will arguably focus on assigning adaptation roles and responsibilities to other government actors, our study importantly names organisations that the UK government has self-identified as needing to collaborate with, or support, if the UK is to adapt. Indeed, Defra’s latest National Adaptation Plan reiterates that ‘Adapting to our changing climate cannot be done by government alone. It will require collaboration across civil society, local authorities, private and public sectors and infrastructure providers’ (Defra 2018: p. 5). Yet, if the UK government is serious about encouraging a more bottom-up and collaborative approach to adaptation, then the diversity of organisations cited, and the importance assigned to them will need to change. A next step here is to explore ‘who’ other adaptation actors—beyond central government—identify as having key roles/responsibilities via documents including publicly available adaptation plans, strategies, policies or ARP reports.

The method we have presented here offers a new, insightful addition to the adaptation tracking literature. It also speaks to recent calls for research that aims to globally assess adaptation actions—as required by Article 7 of the Paris Agreement—by building on Tompkin et al.’s (2018) proposed stocktaking approach. Our method could be upscaled to identify and track actors alongside the categorisation of the adaptation actions they take. Alongside other national adaptation tracking studies (cf. Tompkins et al. 2010; Bierbaum et al. 2013), this method enables a longitudinal analysis of which actors are seen to be essential to making adaptation happen by government departments, identifies differences in the type/size, remits and how capacities of these actors vary, flags up where gaps exist in sectors and where interventions are needed, and how and why the diversity and pattern of these actors changes over time. Importantly, such analyses critically assess whether the global adaptation status of individual countries marries up with the local reality or if high-performing countries share particular characteristics. It also allows us to examine whether high-level government visions and aspirations for adaptation are indeed grounded in reality as set out by more detailed government publications on the topic.

In terms of future research, a global comparison of countries that achieved the maximum adaptation initiative index score and those that scored the lowest could help identify similarities/differences in the diversity of adaptation actor landscapes in each country. Eisenack and Stecker’s (2012) conceptualisation of different functional roles in adaptation actions, ranging from exposure unit, operator and receptor offers another fruitful avenue to explore. Applying this framework could help answer the questions: does one type of actor dominate the landscape, where is a rebalance needed and do particular actor types go hand-in-hand with particular governance styles? Heeding the growing calls for a more consistent, coherent, comparable and comprehensive approach to identifying and tracking adaptation actors and actions (Ford and Berrang-Ford 2016; Tompkins et al. 2018), our research underlines why it is important that we better understand ‘who’ is being asked to adapt.

Notes

DECC was absorbed by the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills to create the new Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy in 2016.

UKCIP drops out of the top 10 for the first time in the fourth quarter, 2013–2015, when its official funding relationship with the UK government ended and the Environment Agency’s Climate Ready team took over.

References

Arnell N, Delaney E (2006) Adapting to climate change: public water supply in England and Wales. Clim Chang 78(2–4):227–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-006-9067-9

Atteridge A, Remling E (2018) Is adaptation reducing vulnerability of redistributing it? WIRES Clim Chang 9(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.500

Berkhout F (2012) Adaptation to climate change by organizations. WIRES Clim Chang 3(1):91–106. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.154

Berkhout F, Hertin J, Gann D (2006) Learning to adapt: organisational adaptation to climate change impacts. Clim Chang 78(1):135–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-006-9089-3

Bierbaum R, Smith JB, Lee A, Blair M, Carter L, Chapin FS, Fleming P, Ruffo S, Stults M, McNeeley S, Wasley E (2013) A comprehensive review of climate adaptation in the United States: more than before, but less than needed. Mitig Adapt Starteg Glob Chang 18(3):361–406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-012-9423-1

Biesbroek R, Klostermann J, Termeer C, Kabat P (2011) Barriers to climate change adaptation in the Netherlands. Climate Law 2(2):181–199. https://doi.org/10.1163/CL-2011-033

Christiansen L, Martinez G, Naswa P (2018) Adaptation metrics: perspectives on measuring, aggregating, and comparing adaptation results. UNEP DTU Partnership. https://unepdtu.org/publications/adaptation-metrics-perspectives-on-measuring-aggregating-and-comparing-adaptation-results/. Accessed 1 Aug 2019

Committee on Climate Change (2017) UK climate change risk assessment 2017: Synthesis report. https://www.theccc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/UK-CCRA-2017-Synthesis-Report-Committee-on-Climate-Change.pdf. Accessed 15 Nov 2018

Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) (2012) UK Climate Change Risk Assessment: Government Report. Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs, London

Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) (2013) The National Adaptation Programme Making the country resilient to a changing climate. Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs, London

Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) (2014) Request for information: Defra spend on low carbon and climate change initiatives 2011–2015. Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs, London

Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) (2018) The National Adaptation Programme and the Third Strategy for Climate Adaptation Reporting. Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs, London

Dupuis J, Biesbroek R (2013) Comparing apples and oranges: the dependent variable problem in comparing and evaluating climate change adaptation policies. Glob Environ Chang 23(6):1476–1487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.07.022

Eisenack K, Stecker R (2012) A framework for analyzing climate change adaptations as actions. Mitig Adapt Starteg Glob Chang 17(3):243–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-011-9323-9

Fitzgerald A, Lupton R (2015) The limits to resilience? The impact of local government spending cuts in London. Local Gov Stud 41(4):582–600. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2015.1040154

Ford JD, Berrang-Ford L (2016) The 4Cs of adaptation tracking: consistency, comparability, comprehensiveness, coherency. Mitig Adapt Starteg Glob Chang 21(6):839–859. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-014-9627-7

Ford JD, Berrang-Ford L, Lesnikowski A, Barrea M, Heymann J (2013) How to track adaptation to climate change: a typology of approaches for national-level application. Ecol Soc 18(3):40. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05732-180340

Ford JD, Berrang-Ford L, Biesbroek R, Araos M, Austin SE, Lesnikowski A (2015) Adaptation tracking for a post-2015 climate agreement. Nat Clim Chang 5(11):967–969. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2744

Green M, Leonard R, Malkin S (2018) Organisational responses to climate change: do collaborative forums make a difference? Geogr Res 56(3):311–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12286

Harvey F (2013) UK’s climate change adaptation team cut from 38 officials to just six. The Guardian. 17.05.2013 https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2013/may/17/uk-climate-change-adaptation-team-cut. Accessed 15 Nov 2018

Hastings A, Bailey N, Gannon M, Besemer K, Bramley G (2015) Coping with the cuts? The management of the worst financial settlement in living memory. Local Gov Stud 41(4):601–621. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2015.1036987

Hedger MM, Connell R, Bramwell P (2006) Bridging the gap: empowering decision-making for adaptation through the UK Climate Impacts Programme. Clim Pol 6(2):201–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2006.9685595

Hoffman V, Sprengel D, Ziegler A, Kolb M, Abegg B (2009) Determinants of coproate adaptations to climate change in winter tourism: an econometric analysis. Glob Environ Chang 19(2):256–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.12.002

HR Wallingford (2012) The UK Climate Change Risk Assessment 2012 Evidence Report. Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs. https://www.preventionweb.net/publications/view/24834. Accessed 1 Aug 2019

Jenkins G, Murphy J, Sexont D, Lowe J, Jones P, Kilsby C (2009) UK climate projections: briefing report. http://ukclimateprojections.metoffice.gov.uk/media.jsp?mediaid=87867. Accessed 15 Nov 2018

Juhola S (2013) Adaptation to climate change in the private and third sector: case study of governance of the Helsinki Metropolitan region. Environ Plann C Gov Policy 31(5):911–925. https://doi.org/10.1068/c11326

Kamperman H, Biesbroek R (2017) Measuring progress on climate change adaptation policy by Dutch water boards. Water Resour Manag 31(14):4557–4570. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-017-1765-8

Klein J, Juhola S, Landauer M (2017) Local authorities and the engagement of private actors in climate change adaptation. Environ Plann C Gov Policy 36(6):1055–1074. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X16680819

Landis JR, Koch GG (1977) The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33(1):159–174. https://doi.org/10.2307/2529310

Lesnikowski AC, Ford JD, Berrang-Ford L, Barrera M, Heymann SJ (2013) How are we adapting to climate change? A global assessment. Mitig Adapt Starteg Glob Chang 20(2):277–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-013-9491-x

Lesnikowski AC, Ford JD, Biesbroek R, Berrang-Ford L, Heymann SJ (2016) National-level progress on adaptation. Nat Clim Chang 6(3):261–264. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2863

Lorenz S, Dessai S, Forster PM, Paavola J (2017) Adaptation planning and the use of climate change projections in local government in England and Germany. Reg Environ Chang 17(2):425–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-016-1030-3

Massey E, Huitema D (2013) The emergence of climate change adaptation as a policy field: the case of England. Reg Environ Chang 13(2):341–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-012-0341-2

Massey E, Huitema D (2016) The emergence of climate change adaptation as a new field of public policy in Europe. Reg Environ Chang 16(2):553–564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-015-0771-8

Noble IR, Huq S, Anokhin YA, Carmin J, Goudou D, Lansigan FP, Osman-Elasha B, Villamizar A (2014) Adaptation needs and options. In: Field CB, Barros VR, Dokken DJ, Mach KJ, Mastrandrea MD, Bilir TE, Chatterjee M, Ebi KL, Otsuki Estrada Y, Genova RC, Girma B, Kissel ES, Levy AN, MacCracken S, Mastrandrea PR, White LL (eds) Climate Change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part A: global and sectoral aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 1–36

Parry ML, Canziani OF, Palutikof JP, Linden PJVD, Hanson CE (2007) Climate Change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Porter JJ, Demeritt D, Dessai S (2015) The right stuff? Informing adaptation to climate change in British Local Government. Glob Environ Chang 35:411–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.10.004

Preston B, Mustelin J, Maloney M (2014) Climate adaptation heuristics and the science/policy divide. Mitig Adapt Starteg Glob Chang 20(3):467–497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-013-9503-x

PriceWaterhouseCoopers (2013) International threats and opportunities of climate change for the UK. http://pwc.blogs.com/files/international-threats-and-opportunities-of-climate-change-to-the-uk.pdf. Accessed 15 Nov 2018

Rhodes C (2018) Financial services: contribution to the UK economy. House of Commons Library, Briefing Paper, 6193. http://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN06193/SN06193.pdf. Accessed 19 Nov 2018

Salvidge R (2016) Environment Agency closes climate change advice service. The Guardian 14.4.2016. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/apr/14/environment-agency-closes-climate-change-advice-service. Accessed 15 Nov 2018

Smit B, Burton I, Klein R, Street R (1999) The science of adaptation: a framework for assessment. Mitig Adapt Starteg Glob Chang 4(3–4):199–213. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009652531101

Stern N (2006) Stern report on the economics of climate change. HM Treasury, London

Swart R, Biesbroek R, Lourenco T (2014) Science of adaptation to climate and science for adaptation. Front Environ Sci 2:29. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2014.00029

Tompkins EL, Eakin H (2012) Managing private and public adaptation to climate change. Glob Environ Chang 22(1):3–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.09.010

Tompkins EL, Adger WN, Boyd E, Nicholson-Cole S, Weatherhead K, Arnell N (2010) Observed adaptation to climate change: UK evidence of transition to a well-adapting society. Glob Environ Chang 20(4):627–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.05.001

Tompkins EL, Vincent K, Nicholls RJ, Suckall N (2018) Documenting the state of adaptation for the global stocktake of the Paris Agreement. WIRES Clim Chang 9:e545. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.545

Turnpenny J, Haxeltine A, Lorenzoni I, O’Riordian T, Jones M (2005) Mapping actors involved in climate change policy networks in the UK. Tyndall Centre Working Paper No. 66. Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research: 1–18

UNFCCC (2016) Paris Agreement. http://www.unfccc.int/files/essential_background/convention/applications/pdf/english_paris_agreement.pdf. Accessed 4 Sept 2018

Walker B, Adger N, Russel D (2015) Institutional barriers to climate change adaptation in centralised governance structures: transport planning in England. Urban Stud 52(12):2250–2266. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014544759

Willows R, Connell R (2003) Climate adaptation: risk, uncertainty, and decision-making. UKCIP Technical Report, Oxford

Acknowledgements

SD acknowledges the support of the UK Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) for the Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy (CCCEP). The authors would also like to thank Maurice Skelton for his technical advice on the data capture design. Any errors are, of course, the responsibility of the authors alone.

Funding

The authors would like to thank the financial support from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007 2013)/ERC Grant agreement no. 284369, which made this research study possible.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Editor: Luis Lassaletta

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lorenz, S., Porter, J.J. & Dessai, S. Identifying and tracking key climate adaptation actors in the UK. Reg Environ Change 19, 2125–2138 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-019-01551-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-019-01551-2