Abstract

The present paper investigates the coupled effect of the supporting soil flexibility and pounding between neighbouring, insufficiently separated equal height buildings under earthquake excitation. Two adjacent three-storey structures, modelled as inelastic lumped mass systems with different structural characteristics, have been considered in the study. The models have been excited using a suit of ground motions with different peak ground accelerations and recorded at different soil types. A nonlinear viscoelastic pounding force model has been employed in order to effectively capture impact forces during collisions. Spring-dashpot elements have been incorporated to simulate the horizontal and rotational movements of the supporting soil. The results of the numerical simulations, in the form of the structural nonlinear responses as well as the time-histories of energy dissipated during pounding-involved vibrations, are presented in the paper. In addition, the variation in storeys peak responses and peak dissipated energies for different gap sizes are also shown and comparisons are made with the results obtained for colliding buildings with fixed-base supports. Observations regarding the incorporation of the soil-structure interaction and its effect on the responses obtained are discussed. The results of the study indicate that the soil-structure interaction significantly influences the pounding-involved responses of equal height buildings during earthquakes, especially the response of the lighter and more flexible structure. It has been found that the soil flexibility decreases storey peak displacements, peak impact forces and peak energies dissipated during vibrations, whereas it usually leads to the increases in the peak accelerations at each storey level.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In conventional design, buildings are generally considered to be fixed at their bases. However, the assumption of fixed-base supports has been proved to be valid only for structures founded on rock or soil of high stiffness. In the reality, flexibility of supporting soil medium results in movements of the foundation leading to the decrease in global stiffness of a structural system (Wakabayashi 1985; Wolf 1987; Stewart et al. 1999a).

Soil-structure interaction (SSI) has captured the interest of many researchers who studied the issues concerning the applications of SSI to buildings through analytical and empirical procedures (see, for example, Stewart et al. 1999a, b; Bhattacharya et al. 2004; Fariborz and Ali 2012; Halabian and Erfani 2013; Spyrakos et al. 2009a, b; Dutta and Rana 2010). Numerous authors considered also the SSI effects in the studies related to bridges (Grange et al. 2011; Chaudhary et al. 2001; Vlassis and Spyrakos 2001; Spyrakos and Vlassis 2002; Sarrazin et al. 2005; Soneji and Jangid 2008). Moreover, the use of energy concepts in the analysis of structures subjected to earthquake motions in the time domain and frequency domain was also investigated in several studies (see, Austin and Lin 2004; Takewaki and Fujita 2009; Yamamoto et al. 2011).

Pounding between neighbouring, inadequately separated buildings with different structural properties during earthquakes is another issue that has recently attracted considerable interest (see, for example, Anagnostopoulos 1988; Maison and Kasai 1992; Karayannis and Favvata 2005; Mahmoud et al. 2008; Anagnostopoulos and Karamaneas 2008; Jankowski 2009; Jankowski 2010, 2012; Dimitrakopoulos et al. 2009; Mahmoud and Jankowski 2010; Polycarpou and Komodromos 2010a, b; Cole et al. 2010; Polycarpou et al. 2013; Efraimiadou et al. 2012). However, most of the studies on earthquake-induced structural pounding were conducted under the assumption that the foundation is rigid. Very limited research work was devoted to study the coupling effect of SSI and pounding on the behaviour of buildings under earthquake excitation. Rahman et al. (2001) studied collisions between adjacent 12 and 6-storey reinforced concrete moment resisting frames incorporating the effects of the soil flexibility and considering impacts at different storey levels. Liolios (2000) introduced a numerical procedure to deal with the dynamic hemivariational inequality problem concerning the elastoplastic-fracturing unilateral contact with friction between neighbouring structures under second-order geometric effects during earthquakes. Chouw (2002) performed an analysis on two impacting buildings linked by a pedestrian bridge taking into account the effect of soil flexibility by employing the boundary element in the Laplace and the time domain. The effects of SSI on mid-column seismic pounding in reinforced concrete buildings of unequal heights under near-field and far-field earthquakes were also studied by Shakya and Wijeyewickrema (2009).

A review of the above cited few papers indicates that the conducted analyses have only concerned collisions between buildings of unequal heights. Moreover, relatively simple linear pounding force models have been adopted to simulate impacts between adjacent structures. The objective of the present paper is to extensively study the coupled effect of both supporting soil flexibility and pounding phenomenon on the nonlinear response of adjacent multi-storey buildings of equal heights with different dynamic properties under various ground motion excitations. In this context, an attempt has also been undertaken to determine the influence of SSI on the amount of energy dissipated by inelastic structural vibrations as well as the amount of energy lost during collisions. Two colliding buildings have been modelled as lumped mass systems assuming rigid as well as flexible base. The nonlinear viscoelastic model has been used to simulate collisions and the spring-dashpot elements have been incorporated to account for the dynamic behaviour of the supporting subsoil.

2 Numerical models

2.1 Models of adjacent buildings

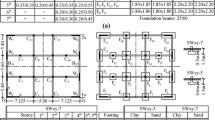

The study described in this paper has been focused on pounding-involved response of three-storey buildings. To analyze the dynamic behaviour of the structures without and with the effect of supporting soil flexibility, two types of systems have been considered (see Fig. 1). The adjacent buildings with fixed bases and the associated systems incorporating SSI effects are characterized by their masses lumped at the floor levels assuming inelastic behaviour during earthquake excitations (see also Mahmoud and Jankowski 2009). In addition, swaying and rocking springs and dashpots (see Spyrakos et al. 2009a; Richart and Whitman 1967) have been used to account for the horizontal and rotational movements of the supporting soil as can be seen for the model incorporating the SSI (Fig. 1b).

2.2 Soil modelling

In the present work, a lumped-parameter model, based indirectly on homogeneous, isotropic and elastic halfspace theory, has been adopted to represent the soil and interaction mechanisms (Richart and Whitman 1967). The discrete model has been formulated for the rectangular foundations embedded in the halfspace and located at the base of the structure to represent coupling between horizontal and rocking vibration modes. Springs and dashpots have been employed in the model in order to account for the transitional and rotational movements of the soil including damping. The parameters of springs and dashpots for swaying and rocking motions can be evaluated using the following formulas (Richart and Whitman 1967):

where \(\nu \) is the Poisson’s ratio of the soil, \(G\) is the shear modulus, \(\beta _x \) and \(\beta _\phi \) are the correct constants of swaying and rocking springs, respectively; \(r_h \) and \(r_r \) denote the equivalent radii of isolated foundation for swaying and rocking springs and \(\rho \) is the density of soil. The maximum shear modulus at low strain, \(G_{\max }\), is related to the shear wave velocity, \(V_s \), according to the following expression (Richart and Whitman 1967):

The shear modulus used in the analysis incorporating the SSI has been reduced in order to maintain closer behaviour of the soil. The modulus reduction curves (\(G/G_{\max }-\gamma \)) are often used to solve dynamic problems when shear strains,\(\gamma \), drive the soil beyond its elastic range. As the soil enters into the inelastic stage, the shear modulus of the soil is reduced substantially what is correspondingly related to the decrease in the shear wave velocity. In the case of the study conducted, the reduced shear modulus \(G\) has been assumed to be 50 % of \(G_{\max }\) calculated according to Eq. 2 (see Richart and Whitman 1967).

2.3 Model of pounding force

In the current study, a nonlinear viscoelastic model has been used to simulate pounding forces induced between adjacent buildings. According to the model, the value of pounding force during contact between \(i\)th (\(i=1,2,3\)) storeys of two adjacent buildings can be calculated as (Jankowski 2005):

where \(\delta _{ii} =(u_i^L -u_i^R -d)\) is the relative displacement, \(d\) is the initial separation gap between buildings, \(\dot{\delta }_{ii} (t)\) is the relative velocity between colliding \(i\)th storeys, \(\bar{{\beta }}\) is the impact stiffness parameter and

is the impact element’s damping. Here, \(m_i^L , \,m_i^R \) is the mass of \(i\)th storey of the left and the right building, respectively; and \(\bar{{\xi }}\) is the impact damping ratio related to the coefficient of restitution, \(e\), which can be defined as (Jankowski 2010):

2.4 Earthquake records

The set of 8 earthquake ground motion records (listed in Table 1) have been used in the study. These records concern the 1979 Imperial Valley, 1984 Morgan Hill, 1992 Lander, 1995 Kobe, 1978 Tabas, 1994 Northridge and 1985 Nahanni earthquakes. They represent strong ground motions with different Peak Ground Acceleration (PGA), magnitude varying between 6.2 and 7.4 and with site-source distance ranging from 0.1 to 17.5 km.

3 Dynamic equations of motions

3.1 Equation of motion ignoring SSI

The equation of motion for the structural models ignoring SSI (see Fig. 1a) can be written as:

where \(\mathbf{M}^{L}, \,\mathbf{C}^{L}\) and \(\mathbf{M}^{R}, \,\mathbf{C}^{R}\)are the matrices of masses and damping coefficients for the left and the right building, respectively; \(\mathbf{R}^{L}\) and \(\mathbf{R}^{R}\) are vectors consisting of the system inelastic resisting forces; \(\mathbf{U}^{L}, \,\dot{\mathbf{U}}^{L}, \,\ddot{\mathbf{U}}^{L}\) and \(\mathbf{U}^{R}, \,\dot{\mathbf{U}}^{R}, \,\ddot{\mathbf{U}}^{R}\) denote the displacement, velocity and acceleration vectors for the left and the right structure, respectively; F is the pounding force vector and \(\ddot{\mathbf{U}}_g \) is the vector of ground motion acceleration.

Let \(m_i^L ,\;c_i^L ,\;R_i^L \) and \(m_i^R ,\;c_i^R ,\;R_i^R\, (i=1,2,3)\) be the masses, the viscous damping coefficients and the inelastic storey shear forces for the left and the right building, respectively. Then, the matrices and vectors of Eq. 6 can be defined as:

During the elastic stage, \(R_i^L \) and \(R_i^R \) take the form: \(R_i^L =k_i^L (u_i^L -u_{i-1}^L ), \,R_i^R =k_i^R (u_i^R -u_{i-1}^R )\) and during the plastic stage: \(R_i^L =\pm f_{yi}^L , \,R_i^R =\pm f_{yi}^R \), where \(k_i^L , \,k_i^R \) and \(f_{yi}^L , \,f_{yi}^R \) are the storey initial stiffness coefficients and yield forces for the left and the right building, respectively; \(u_i^L ,\;\dot{u}_i^L ,\;\ddot{u}_i^L \) and \(u_i^R ,\;\dot{u}_i^R ,\;\ddot{u}_i^R \) denote the displacement, velocity and acceleration of the left and right structure, respectively. Furthermore:

3.2 Equation of motion considering SSI

The equation of motion for the structural models considering SSI (see Fig. 1b) can be written as:

The matrices and vectors of Eq. 9 for colliding two buildings of equal height, \(h\), incorporating the soil flexibility effect in terms of the horizontal and rotational soil movements \(u_0^L , \,u_0^R , \,\varphi ^{L}\) and \(\varphi ^{R}\) can be expressed as (compare Spyrakos et al. 2009a):

3.3 Numerical procedure

A Newmark step-by-step method (Chopra 2006) with a constant step size of 0.001 s has been employed to solve the governing equations of motions (6) and (9) and to calculate various structural and energy response quantities. In order to attain high degree of numerical stability, parameters: \(\gamma = 0.5\) and \({\beta } = 0.25\), corresponding to the constant average acceleration approach, have been applied.

4 Energy response

The seismic input energy imparted to a building, when a structure is seismically excited, can be divided into two parts. One part is related to the temporarily stored energy in the form of kinetic and strain energy. The other part is the energy dissipated through damping and inelastic deformation in the components of the structure. For a single degree-of-freedom system, the input energy to the structure, IE, the absorbed kinetic energy, KE, the hysteretic or yielding energy, HE, and the recoverable elastic strain energy, SE, can be defined at each time, \(t\), as (Zahrah and Hall 1984):

For the three-storey buildings (see models at Fig. 1), the input energy at \(i\)th (\(i=1,2,3\)) storey level for the left (upper index \(L\)) and the right (upper index \(R\)) structure can be written as:

Similarly, the kinetic energy, damping energy, yielding energy and elastic strain energy at each storey level take the form:

5 Numerical results

Two adjacent three-storey building models without and with SSI have been considered in the numerical simulations. The structural properties (see Table 2) have been set so as the adjacent buildings have different (substantially different) dynamic characteristics and hence pounding between them takes place at inadequate separation distances.

The following parameters of the nonlinear viscoelastic model of pounding force have been incorporated in the study: \(\bar{{\beta }}=2.75\times 10^{9}\,\text{ N/m}^{{3}/{2}}, \,\bar{{\xi }}=0.35 \quad (e=0.65)\) (see Jankowski 2008). In order to simulate the rotational and horizontal movements of the supporting soil, spring-dashpot elements have been utilized with the properties of the stiffness of swaying and rocking springs and the damping of dashpots evaluated using the formula given by Eq. 1. The soil mass density and Poisson’s ratio have been taken as equal to: \(\gamma =1.89\times 10^{3}\,\text{ kg/m}^{3}\) and \(\nu =0.3\), respectively. The shear wave velocity has been given by \(V_s =150\) m/sec. The radii of equivalent circular foundation for swaying and rocking have been estimated as equal to: \(r_h =r_r =4\,\text{ m}\) (Takewaki 2005).

5.1 Time-history response

The nonlinear dynamic analyses have been carried under a set of earthquake records summarized in Table 1. The examples of the numerical results for the three-storey colliding buildings without and with SSI are presented in Tables 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 and Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15.

The displacement time-histories without and with SSI considering and ignoring pounding effect (gap size of 0.05 m) under the Imperial Valley earthquake record are shown in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively. The results indicate that the incorporation of rotational and horizontal movements of the supporting soil results in the reduction in displacements of the storeys of both buildings. Moreover, the discrepancies between the obtained peak displacements considering SSI and those peak displacements obtained ignoring SSI are much more pronounced for the storeys of the left (lighter and more flexible) building. For example, the peak displacements for the case with pounding obtained for the first, the second and the third storey of the left building ignoring SSI under the Imperial Valley ground motion record are: 0.1429, 0.1834 and 0.2009 m, respectively; while the corresponding values for the case incorporating SSI are: 0.0332, 0.0606 and 0.0768 m, respectively. On the other hand, the storeys of the right building with rigid base induce peak displacements of: 0.0117, 0.0161 and 0.0189 m and with flexible base produce peak displacements equal to: 0.0029, 0.0044 and 0.0062 m for the first, the second and the third storey, respectively. Moreover, the peak displacements for sufficiently separated buildings (i.e. for the case without collisions) obtained for the first, the second and the third storey of the left building ignoring SSI under the Imperial Valley ground motion record are: 0.0830, 0.1232 and 0.1449 m, respectively; while the corresponding values for the case incorporating SSI are: 0.0332, 0.0608 and 0.0763 m, respectively. On the other hand, the storeys of the right building with rigid base induce peak displacements of: 0.0117, 0.0149 and 0.0095 m and with flexible base produce peak displacements equal to: 0.0029, 0.0042 and 0.0048 m for the first, the second and the third storey, respectively. Similar results have also been obtained using the set of other earthquake records (see Tables 3, 4). As it can be seen from Tables 3 and 4, the consideration of SSI decreases the peak displacements of buildings with and without collisions. However, the occurrence of pounding causes substantial amplification of the displacement response of the lighter and more flexible building. On the other hand, the displacement response of the heavier building is nearly unaffected by collisions.

Figure 4 shows pounding force time-histories without and with SSI under the Imperial Valley, Tabas, Northridge and Nahanni ground motions considering the separation gap between neighbouring buildings of 0.05 m. The values of peak pounding forces are also summarized in Table 5. It can be seen from Fig. 4 and Table 5 that ignoring SSI produces higher impact forces during collisions, as compared to the values obtained with incorporation of soil flexibility effects. Consequently, those higher forces act on buildings leading to higher displacements, which can be so large that the structures may not come back into contact again and the permanent deformation due to yielding of the left structure may take place (see Fig. 2). This generally leads to the decrease in the number of impacts, as compared to the number of impacts for the case when soil flexibility effect is considered (see collisions at third storey level under the Imperial Valley and Nahanni earthquake records—Fig. 4a, d).

Figure 5 shows the acceleration time-histories of colliding buildings without and with SSI under the Tabas earthquake record. A light decrease in the obtained response can be observed as a result of soil flexibility incorporation. Although, a number of significant cycles of large amplitude accelerations decreases due to the incorporation of SSI, the peak acceleration value is larger. It should be mentioned, however, that the spikes observed in the time-histories with SSI results mainly from the impact response of the horizontal spring-dashpot elements used to simulate the behaviour of soil (see Fig. 1b). This effect is especially visible in the case of the acceleration time-histories for the first storeys of both buildings, for which spikes are present only in the responses with SSI, whereas collisions at the level of the first storeys do not take place (see lack of collisions for the first storeys at Fig. 4b). It should also be underlined that the spikes observed in the case of responses incorporating SSI are shorter in duration and because of that they do not induce large displacements (see Fig. 2), even that they are usually characterized by larger peak acceleration values comparing to the spikes observed in the time-histories without SSI. Figure 5 also indicates that higher induced peak acceleration values can be expected for higher storeys. The results presented in Tables 3 and 4 concerning the peak accelerations under other ground motions records also confirm the above observations.

Shearing force time-histories without and with SSI for colliding buildings under the Nahanni earthquake record are shown in Fig. 6. It can be seen from the figure that interactions between adjacent structures incorporating the soil flexibility result in the decrease in the obtained shearing forces for the storeys of the left and the right building. Moreover, the results shown in Fig. 6 indicate that collisions may lead to yielding in the case when SSI effects are ignored (see horizontal line segments).

Figure 7 shows the time-histories of energy dissipated by damping for the case of buildings without SSI, as compared to the case when SSI is taken into account, under the Northridge earthquake record. The maximum inelastic energy response quantities obtained under other earthquake records are also summarized in Tables 6 and 7. It can be seen from Fig. 7 that incorporating the effect of soil flexibility results in the decrease in the amount of energy dissipated. Moreover, the curves for each floor level show a sudden jump at about the same time when collision between buildings occurs (see Fig. 4c). Ignoring SSI visibly amplifies this sudden jump leading to the increase in the amount of dissipated energy for all the considered storey levels of colliding buildings. Figure 7, as well as Tables 6 and 7, clearly demonstrate that the influence of SSI on the obtained dissipated damping energy of the storeys of adjacent buildings is significant. The amount of the dissipated damping energy for the left building storeys during collisions under the Nahanni ground motion record without SSI is equal to: 37.72, 86.92 and 120.80 kNm for the first, the second and the third storey, respectively. On the other hand, the corresponding results for the case with SSI are: 14.94, 38.15 and 52.84 kNm. Moreover, the results for the right building storeys without SSI gives the following values: 66.83, 185.00 and 276.80 kNm, whereas with SSI incorporation: 6.26, 11.86 and 14.35 kNm have been obtained for the first, the second and the third storey, respectively. The above results indicate that the storeys of the right building are capable to dissipate more energy comparing to the storeys of the left structure.

The time-histories of energy dissipated by yielding for the case without and with SSI under the Imperial Valley earthquake record are presented in Fig. 8. It is apparent that the obtained energy responses are highly affected by the simultaneous effect of collisions between buildings and the supporting base flexibility. As it can be seen from Fig. 8, the induced pounding forces cause sudden increase in the dissipated yielding energy responses for the storeys of the left and the right building for the case without and with SSI. However, the incorporation of the base flexibility significantly decreases the amount of the energy dissipated by yielding (see Fig. 8 as well as Tables 6, 7). The storeys of colliding buildings keep nearly constant values of dissipated yielding energy after the sudden jump, i.e. at the end of impact between buildings.

Figure 9 presents the absorbed kinetic energy time-histories at each storey of colliding buildings with fixed bases as well as for the case of flexible soil conditions under the Imperial Valley earthquake record. It can be seen from the figure that, for all the storeys of both buildings, high kinetic energy has been induced during the time of collisions (compare with Fig. 4a) for the case without and with SSI. However, the incorporation of soil flexibility substantially decreases the absorbed kinetic energy (see also Tables 6, 7). Moreover, it has been noticed that the kinetic energy absorbed at levels of lower storeys show smaller values comparing to the values obtained at higher storey levels. Moreover, the storeys of the left (lighter and more flexible) building absorb higher values of kinetic energy comparing to the energy absorbed by the storeys of the right (heavier and stiffer) building. As it could be expected, the stored kinetic energy represents small amount of energy comparing to the amount of energy dissipated by damping and yielding.

5.2 Peak response for different seismic gaps

Figure 10 shows the values of the peak displacements of colliding buildings with respect to the initial separation gap, \(d\), varying in the range of 0–20 cm, under the Morgan Hill earthquake. It has been noted that the peak displacement curves for all the storeys of the left building without SSI follow a similar trend. The results show an increase in the peak displacement up to a certain maximum level, which is followed by a decrease trend to a certain minimum value and then peak values are kept constant for wider gap sizes. On the other hand, the peak displacement curves obtained for the storeys of the right building without SSI show initially slight increase, which is followed by slight decrease trend as the separation gap increases, and remain nearly unchanged for further increase in the separation gap. It can also be seen from Fig. 10 that the influence of the seismic gap on the peak displacements of the storeys of both building with SSI is rather small, especially for narrow seismic gaps and remain nearly unchanged for further increase in the seismic gap value. Moreover, it can be seen from the figure, that for narrow gaps the storeys of the left building provide smaller values of peak displacements, as compared to those obtained for the case of neglecting the soil flexibility. On the other hand, the difference is not so big for wider gap size values. For the right building storeys, the incorporation of the SSI makes the storeys peak displacements very insensitive to the variation in the separation distance and results in much smaller peak displacement values, as compared to those obtained for the storeys with rigid base. It can be concluded, based on the results presented in Fig. 10, that the SSI generally reduces the obtained peak displacements, especially for small seismic gaps.

Figure 11 presents the values of peak accelerations of colliding buildings for different separation gaps, varying in the range of 0–30 cm, under the Kobe earthquake record. It has been found that the incorporation of SSI influences the peak acceleration responses for all storey levels. As it can be seen from the figure, the incorporation of the soil flexibility usually leads to the increase in the peak accelerations of the storeys of both buildings for all the considered gap size values. The results indicate that, as the separation distance increases, the peak accelerations increase up to a certain maximum value and with further increase in the separation gap a decrease trend can be observed for all the storeys of colliding buildings. Moreover, ignoring the soil flexibility emphasizes the sensitivity of the obtained peak accelerations of the storeys of the left building with relation to the separation gap. In this case, the storeys show higher peak accelerations at smaller gaps and when the separation gap gets wider a decrease trend can be observed. Then, the peak acceleration values remain nearly unchanged for further increase in the separation gap value. On the other hand, the storeys of the right building induce peak responses that show nearly unchanged values with the variations in seismic gap.

The influence of the variation in the separation gap on the peak pounding forces during collisions between buildings with and without the incorporation of SSI under the Northridge earthquake is presented in Fig. 12. As it can be seen from the figure, higher storeys collide at wider gap sizes for the case without and with SSI. It has been found that the incorporation of the flexibility of the supporting soil leads to significant reduction in the induced peak forces, especially at higher storey levels. Moreover, with the increase in the separation distance the peak forces due to impact generally increase up to a certain maximum value and with further increase in the separation gap the decrease trend is observed for the left and the right building.

Figure 13 illustrates the peak energy dissipated by damping at each of the storey levels of the colliding buildings without and with SSI under the Morgan Hill ground motion with respect to the separation gap between structures. The results show that the incorporation of the soil flexibility leads to the reduction in the peak energy responses for all the storeys. It can be seen from Fig. 13 that the shapes of the obtained curves for the storeys of the left building without and with SSI have similar trends. It has been found that, with the increase in the separation gap, the peak dissipated damping energy initially increases and then slightly decreases to become nearly constant for higher gap sizes. On the other hand, the storeys of the right building show nearly constant values for all gap sizes considered. It should be underlined, however, that the variations between the obtained peak responses for considering and ignoring SSI are much more pronounced for the storeys of the right building. The amount of the dissipated energy is much higher for the storeys of the right building comparing to the energy dissipated by the storeys of the left structure.

The peak energy dissipated by yielding for colliding buildings considering and ignoring the base soil flexibility effect with respect to the separation gap between structures under the Nahanni earthquake are presented in Fig. 14. The results indicate that the consideration of base soil flexibility results in nearly constant values of peak energy dissipated by yielding for different seismic gaps. On the other hand, neglecting SSI significantly affects the obtained peak values for the storeys of the left building and the influence is more pronounced when the seismic gap is small. However, relatively small variations between the obtained peak responses have been obtained for the storeys of the right building for different seismic gaps. Moreover, similarly to the case of the peak dissipated damping energy, the storeys of the right building dissipate larger amount of yielding energy comparing to the amount of energy dissipated by the storeys of the left structure.

Figure 15 presents the variation in the peak absorbed kinetic energy for pounding between buildings considering and ignoring the base soil flexibility for different values of the separation gap under the Imperial Valley earthquake record. The figure shows a substantial decrease in the peak absorbed kinetic energy values due to the incorporation of SSI, especially for the storeys of the right building. The results also indicate that neglecting SSI significantly influences the obtained peak values of both building and the influence is larger when the seismic gap is small. It can be seen form Fig. 15 that, with the increase in separation gap, an increase trend can be observed up to a certain maximum value, which is followed by a decrease trend and with further increase in the seismic gap the obtained peak absorbed kinetic energy values remain nearly unchanged. It can also be noticed at Fig. 15a that minor differences between the peak kinetic energy responses of the lower storeys of the left building with and without SSI have been obtained at larger gaps. On the other hand, a significant variation between the obtained peak energy responses for considering and ignoring the SSI is visible for the storeys of the right building for all the considered seismic gaps. It is also worth mentioning that the storeys of the left building absorb larger amount of kinetic energy comparing to the amount of energy absorbed by the storeys of the right building.

The results from the nonlinear analysis of the insufficiently separated multi-storey buildings shown in Figs. 7, 8, 9 and 13, 14, 15 reveal that the SSI decreases the dissipated and absorbed energy demand and consequently leads generally to the reduction in structural responses. It is worth noting that the measure of structural damage is highly related to the ductility and hysteretic energy demands, i.e. the hysteretic or yielding energy demand is an important factor for the damage index (see Symans et al. 2008). Generally speaking, the smaller the hysteretic energy demand the smaller the damage index measure. Therefore, the results of the present study indicate that ignoring the soil flexibility effect overestimates the damage measure of the colliding structures under earthquake excitation.

6 Conclusions

The influence of the soil flexibility on the nonlinear structural responses as well as the energy responses of colliding equal height buildings under a set of ground motion records has been investigated in this paper. The results in terms of the response time-histories as well as the relations between the peak responses and the separation gap have been presented. The comparison between the results for the three-storey buildings without and with SSI has been discussed.

The results of the first stage of the study indicate that considering the horizontal and rotational movements of the supporting soil substantially influences the responses of colliding buildings, especially the response of the lighter and more flexible structure. It has been found that SSI decreases the peak displacements, impact forces and inelastic shearing forces, whereas usually leads to the increase in peak accelerations at each storey level. It has also been observed that incorporation of SSI in the analysis results in the increase of number of impacts at the top storey level and prevents from pounding between lower storeys. Furthermore, the soil flexibility considerably reduces the energy response quantities of equal height buildings in terms of the absorbed kinetic energy, the dissipated damping energy and the dissipated yielding energy.

The results of further study, conducted for different values of separation gaps between buildings, confirm that the incorporation of the soil flexibility may result in significant reduction in the structural peak displacements and impact forces under various ground motion excitations. On the other hand, the increase in the peak accelerations at each storey level has also been observed for nearly all gap size values considered. Moreover, the peak energy response curves obtained for the case with SSI show the decrease trend, as compared to the corresponding peak values without SSI. The influence of the separation seismic gap on the peak structural responses and the energy responses has been found to be significant, especially for the lighter and more flexible building.

The analysis described in this paper has concerned the case of two three-storey buildings. Further detailed investigations focused on the response of adjacent buildings with different heights are needed so as to extend our knowledge on pounding between structures incorporating SSI. Also the case of multiple earthquakes effects, considering the deterministic as well as stochastic approach, would be an interesting field for future investigations (Hatzigeorgiou and Liolios 2010; Jankowski and Walukiewicz 1997).

References

Anagnostopoulos SA (1988) Pounding of buildings in series during earthquakes. Earthq Eng Struct Dyn 16(3):443–456

Anagnostopoulos S, Karamaneas CE (2008) Use of collision shear walls to minimize seismic separation and to protect adjacent buildings from collapse due to earthquake-induced pounding. Earthq Eng Struct Dyn 37(12):1371–1388

Austin M, Lin WJ (2004) Energy balance assessment of base-isolated structures. Eng Mech 130(3):347–358

Bhattacharya K, Dutta S, Dasgupta CS (2004) Effect of soil-flexibility on dynamic behaviour of building frames on raft foundation. Sound Vib 274(1–2):111–135

Chaudhary MTA, Abé M, Fujino Y (2001) Identification of soil-structure interaction effect in isolated bridges from earthquake records. Soil Dyn Earthq Eng 21(8):713–725

Chopra AK (2006) Dynamics of structures, 3rd edn. Prentice Hall, New York

Chouw N (2002) Influence of soil-structure interaction on pounding response of adjacent buildings due to near-source earthquakes. J Appl Mech 5:543–553

Cole GL, Dhakal RP, Carr AJ, Bull DK (2010) Building pounding state of the art: identifying structures vulnerable to pounding damage. In: NZSEE 2010—New Zealand Society for earthquake engineering annual conference, Wellington, New Zealand, paper P11

Dimitrakopoulos E, Makris N, Kappos AJ (2009) Dimensional analysis of the earthquake-induced pounding between adjacent structures. Earthq Eng Struct Dyn 38(7):867–886

Dutta SC, Rana R (2010) Inelastic seismic demand of low-rise buildings with soil-flexibility. Int J Non-linear Mech 45(4):419–432

Efraimiadou S, Hatzigeorgiou GD, Beskos DE (2012) Structural pounding between adjacent buildings: the effects of different structures configurations and multiple earthquakes. In: Proceedings of the 15th world conference on earthquake engineering, Lisbon, Portugal, 24–28 September 2012

Fariborz AN, Ali TR (2012) Nonlinear dynamic response of tall buildings considering structure-soil-structure effects. Struct Des Tall Special Build (in press)

Grange S, Botrugno L, Kotronis P, Tamagnini C (2011) The effect of soil-structure interaction on a reinforced concrete viaduct. Earthq Eng Struct Dyn 40(1):93–105

Halabian AM, Erfani M (2013) The effect of foundation flexibility and structural strength on response reduction factor of RC frame structures. Struct Des Tall Special Build 22:1–28

Hatzigeorgiou GD, Liolios AA (2010) Nonlinear behaviour of RC frames under repeated strong ground motions. Soil Dyn Earthq Eng 30(10):1010–1025

Jankowski R (2005) Non-linear viscoelastic modelling of earthquake-induced structural pounding. Earthq Eng Struct Dyn 34(6):595–611

Jankowski R (2008) Earthquake-induced pounding between equal height buildings with substantially different dynamic properties. Eng Struct 30(10):2818–2829

Jankowski R (2009) Non-linear FEM analysis of earthquake-induced pounding between the main building and the stairway tower of the Olive View Hospital. Eng Struct 31(8):1851–1864

Jankowski R (2010) Experimental study on earthquake-induced pounding between structural elements made of different building materials. Earthq Eng Struct Dyn 39(3):343–354

Jankowski R (2012) Non-linear FEM analysis of pounding-involved response of buildings under non-uniform earthquake excitation. Eng Struct 37:99–105

Jankowski R, Walukiewicz H (1997) Modeling of two-dimensional random fields. Probab Eng Mech 12(2):115–121

Karayannis CG, Favvata MJ (2005) Earthquake-induced interaction between adjacent reinforced concrete structures with non-equal heights. Earthq Eng Struct Dyn 34(1):1–20

Liolios A (2000) A linear complementarity approach for the non-convex seismic frictional interaction between adjacent structures under instabilizing effects. J Global Optim 17(1–4):259–266

Mahmoud S, Jankowski R (2009) Elastic and inelastic multi-storey buildings under earthquake excitation with the effect of pounding. J Appl Sci 9(18):3250–3262

Mahmoud S, Jankowski R (2010) Pounding-involved response of isolated and non-isolated buildings under earthquake excitation. Earthq Struct 1(3):3250–3262

Mahmoud S, Chen X, Jankowski R (2008) Structural pounding models with Hertz spring and nonlinear damper. J Appl Sci 8(10):1850–1858

Maison BF, Kasai K (1992) Dynamics of pounding when two buildings collide. Earthq Eng Struct Dyn 21(9):771–786

Polycarpou PC, Komodromos P (2010a) Earthquake-induced poundings of a seismically isolated building with adjacent structures. Eng Struct 32(7):1937–1951

Polycarpou PC, Komodromos P (2010b) On poundings of a seismically isolated building with adjacent structures during strong earthquakes. Earthq Eng Struct Dyn 39(8):933–940

Polycarpou PC, Komodromos P, Polycarpou AC (2013) A nonlinear impact model for simulating the use of rubber shock absorbers for mitigating the effects of structural pounding during earthquakes. Earthq Eng Struct Dyn 42:81–100

Rahman AM, Carr AJ, Moss PJ (2001) Seismic pounding of a case of adjacent multiple-storey buildings of differing total heights considering soil flexibility effects. Bull NZ Soc Earthq Eng 34:140–159

Richart FE, Whitman RV, ASCE (1967) Comparison of footing vibration tests with theory. Soil Mech Found Div 93(SM6):143–168

Sarrazin M, Moroni O, Roesset JM (2005) Evaluation of dynamic response characteristics of seismically isolated bridges in Chile. Earthq Eng Struct Dyn 34(4–5):425–448

Shakya K, Wijeyewickrema AC (2009) Mid-column pounding of multi-story reinforced concrete buildings considering soil effects. Adv Struct Eng 12(1):71–85

Soneji BB, Jangid RS (2008) Influence of soil-structure interaction on the response of seismically isolated cable-stayed bridge. Soil Dyn Earthq Eng 28(4):245–257

Spyrakos CC, Vlassis AG (2002) Effect of soil-structure interaction on seismically isolated bridges. Earthq Eng 6(3):391–429

Spyrakos CC, Koutromanos IA, Maniatakis CA (2009a) Seismic response of base-isolated buildings including soil-structure interaction. Soil Dyn Earthq Eng 29(4):658–668

Spyrakos CC, Maniatakis CA, Koutromanos IA (2009b) Soil-structure interaction effects on base-isolated buildings founded on soil stratum. Eng Struct 31(3):729–737

Stewart JP, Fenves GL, Seed RB (1999a) Seismic soil-structure interaction in buildings, I: analytical methods. Geotech Geoenviron Eng 125(1):26–37

Stewart JP, Seed RB, Fenves GL (1999b) Seismic soil-structure interaction in buildings, II: empirical findings. Geotech Geoenviron Eng 125(1):38–48

Symans MD, Charney FA, Whittaker AS, Constantinou MC, Kircher CA, Johnson MW, McNamara RJ (2008) Energy dissipation systems for seismic applications: current practice and recent developments. J Struct Eng 134(1):3–21

Takewaki I (2005) Bound of earthquake input energy to soil-structure interaction systems. Soil Dyn Earthq Eng 25(7–10):741–752

Takewaki I, Fujita K (2009) Earthquake input energy to tall and base-isolated buildings in time and frequency dual domains. Struct Des Tall Special Build 18(6):589–606

Vlassis AG, Spyrakos CC (2001) Seismically isolated bridge piers on shallow soil stratum with soil-structure interaction. Comput Struct 79(32):2847–2861

Wakabayashi M (1985) Design of earthquake-resistant buildings. McGraw-Hill, TX

Wolf JP (1987) Dynamic soil-structure interaction. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Yamamoto K, Fujita K, Takewaki I (2011) Instantaneous earthquake input energy and sensitivity in base-isolated building. Struct Des Tall Special Build 20(6):631–648

Zahrah TF, Hall WJ (1984) Earthquake energy absorption in SDOF structures. J Struct Eng ASCE 110(8): 1757–1772

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahmoud, S., Abd-Elhamed, A. & Jankowski, R. Earthquake-induced pounding between equal height multi-storey buildings considering soil-structure interaction. Bull Earthquake Eng 11, 1021–1048 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10518-012-9411-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10518-012-9411-6