Abstract

In this paper, we examine the relationship between various Christian denominations and attitude and behavior regarding consumption of socially responsible (SR) products. Literature on the relationship between religiosity and pro-social behavior has shown that religiosity strengthens positive attitudes towards pro-social behavior, but does not affect social behavior itself. This seems to contradict the theory of planned behavior that predicts that attitude fosters behavior. One would therefore expect that if religiosity encourages attitude towards SR products, it would also increase the demand for them. We test this hypothesis for four affiliations (non-religious, Catholic, Orthodox Protestant, and Other Protestant) on a sample of 997 Dutch consumers, using structural equation modeling. We find that Christian religiosity, indeed, increases positive attitude towards SR products, except for the Orthodox Protestant affiliation. In accordance with the theory of planned behavior, attitude is found to increase the demand for SR products. We find no evidence of hypocrisy (in the sense that religiosity increases pro-social attitude without affecting behavior in the case of SR products) for any of the Christian denominations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Socially responsible (SR) consumption has received increasing attention in academic literature (Roe et al. 2001; Robinson and Smith 2002; Shaw and Shiu 2003; Vermeir and Verbeke 2006; De Pelsmacker and Janssen 2007; McCluskey et al. 2009; Welsch and Kühling 2009; Bennett and Blaney 2002; Moon and Balasubramanian 2003; Auger et al. 2003; Loureiro and Lotade 2005; Casadesus-Masanell et al. 2009). Research has shown that the demand for SR products depends on the intention to buy SR products and the attitude towards them. Other studies have researched the influence of socio-demographic characteristics on the demand for SR products (Blend and van Ravenswaay 1998; Batley et al. 2001; Loureiro et al. 2002; Jensen et al. 2002; Millock et al. 2002; Ivanova 2005; De Pelsmacker et al. 2005). This type of research has shown that the demand for SR products depends positively on income, education, and (female) gender, whereas some studies also find that demand for SR products rises with age.

Relatively little attention has been paid, however, to the role of religion in the demand for SR products. Studies into the relationship between religion and other types of pro-social behavior have shown that religiosity discourages a-social attitudes. For example, McNichols and Zimmerer (1985) find that religious beliefs enforce negative attitudes towards certain unacceptable behavior. Vitell et al. (2005, 2006, 2007) find that more religiously oriented individuals are more likely to qualify questionable consumer behaviors as wrong. Furthermore, religiosity is also found to encourage pro-social attitudes. For example, Ramasamy et al. (2010) find that religiosity has a significant influence on corporate social responsibility support among consumers. However, the strong association between religiosity and moral attitudes is not reflected by a corresponding relationship between religion and actual pro-social behavior. Hansen et al. (1995) show that the positive intentions of religious people to help others seem rather unrelated to spontaneous helping behaviors. This ‘attitude versus behavior gap’ with respect to religion is confirmed by many studies (Batson and Flory 1990; Batson et al. 1999; Ji et al. 2006; Hood et al. 2009). This would indicate that religiosity does not really foster pro-social behavior, but rather increases hypocrisy by enlarging the gap between attitude and behavior.

The question arises whether this also holds for the case of SR products. As far as we know, no research has been done into this specific type of pro-social attitude and behavior. In our paper, we aim to fill this gap by researching the relationship between religiosity and the attitude towards SR products and how both affect behavior towards SR products. Starting from the theory of planned behavior of Ajzen (1991), we will analyze the influence of religiosity on attitude towards SR products and research whether religiosity also affects the demand for SR products or merely increases the gap between attitude and behavior, as the literature on religiosity and pro-social behavior suggests. Hence, the research question is twofold: (1) Does religiosity encourage a positive attitude towards SR products? (2) How does religiosity affect the demand for SR products?

To investigate these research questions empirically, we surveyed a large sample of households from non-religious and various Christian religious denominations in the Netherlands (n = 997) with regard to the attitude and buying behavior of SR products. Whereas many papers focus on one SR product, we selected four SR products (fair trade coffee, organic meat, free-range eggs, and fair trade chocolate sprinkles) that link to different types of responsibilities. Whereas fair trade coffee and fair trade chocolate sprinkles focus on responsibility towards the well being of other human beings (fairness, environmental issues), organic meat and free-range eggs relate to responsibility towards the well being of animals. The Netherlands is interesting for examining the relationship between religiosity and individual decision-making as there is a considerable variety in types of religious beliefs (Renneboog and Spaenjers 2009; Mazereeuw et al. 2014). Moreover, the distinction between religious and non-religious people is not as blurred as in other countries because the people in The Netherlands who call themselves religious are usually committed and practicing believers (Halman et al. 2005). We use structural equation modeling (SEM) to test the relationships between religiosity, attitude, and behavior towards SR products.

The structure of the article is as follows. In section “Theoretical Background,” we give the theoretical background of the theory of planned behavior and present the hypotheses. Section “Methodology” describes the methodology. In section “Estimation Results,” the results of the empirical analysis are presented. In section “Discussion,” the results are discussed. Section “Policy Implications and Future Research” closes with policy implications and possibilities for future research.

Theoretical Background

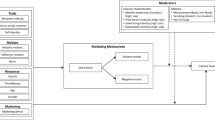

The conceptual framework of the model is summarized in Fig. 1.

In literature, a common starting point for studying the demand for SR products is the theory of planned behavior, an offshoot of the theory of reasoned action, by Fishbein and Ajzen (1975). According to the theory of planned behavior, behavior is guided by social attitudes. Ajzen (1991) defines attitude as the degree to which a person has a favorable or unfavorable evaluation or appraisal of the behavior in question. Attitude can stem from emotional reactions to an object, can be based on past behaviors and experiences with the object, or can be based on some combination of these sources of evaluative information (Fazio 2007). The theory of planned behavior assumes that attitude is the key to understand behavior, but research in the late sixties showed that attitude is often a poor predictor of actual behavior (Wicker 1969). But more recent research showed that an important condition for the relationship between attitudes and behavior is the principle of compatibility: if the measure of attitude matches the measure of the behavior in terms of the level of generality or specificity, high correlations between attitude and behavior are found (Ajzen and Fishbein 2005). The relationship between attitude and behavior has also been supported by recent research into SR products. For example, De Pelsmacker and Janssen (2007) operationalize attitude to SR products by, among others, concern about SR products and the price acceptability of SR products. They found that most participants in their Belgian focus group would be more prone to buying SR products if they had concern about the fair trade issue and if the prices of fair trade products were more acceptable to them. Dickson (2001) showed that in the US, concern about sweatshop practices is significantly correlated with the likelihood of a person buying textiles with a ‘no sweat’ label. Based on this, we hypothesize:

H1

A positive attitude towards SR products increases the demand for SR products

Besides a positive attitude, situational factors such as the social norms prevailing in the social environment of the consumer may also affect the demand for SR products. In the original model of Fishbein and Ajzen (1975), the social dimension of the individual choice behavior is captured by the ‘subjective norm.’ Subjective (or social) norm is related to how other people who are important to the agent regard the behavior. Consideration of the likely approval or disapproval of a behavior by friends, family members, or coworkers is assumed to lead to perceived social pressure to engage or not engage in the behavior (Ajzen and Fishbein 2005). The opinion of ‘relevant others’ (key persons in the social network of the consumer) about buying SR products may therefore be a reason for buying SR products (Biel and Thøgersen 2007). This is confirmed by empirical studies. For example, in their UK study, Shaw and Shiu (2003) found an important effect of social norms on buying fair trade products. Similar findings were obtained for the US (Robinson and Smith 2002), Germany (Welsch and Kühling 2009), and Belgium (Vermeir and Verbeke 2006). We therefore hypothesize that the subjective norm may affect the behavior towards SR products directly, since the individual will experience pressure to conform to the subjective norm set by the community to which he or she belongs:

H2

A positive subjective norm to buy SR products increases the demand for SR products

Besides a direct influence of subjective norm on the demand for SR product, it is likely that it will affect the demand for SR products also indirectly, by affecting the attitude towards SR products. According to the Social Identity Theory, a person has multiple social identities derived from memberships of various social groups (Tajfel 1982). The need for a social identity [e.g., that part of the individuals’ self-concept which derives from their knowledge of their membership of a social group (Tajfel 1982, p. 24)] is underpinned by the human need for a positive self-esteem (Hogg 2001). The participation in a specific social group may trigger the individual to think and act on basis of the social identity that he or she derives from the membership of this community (Turner et al. 1987). A similar line of reasoning is given by symbolic interactionism theory (Wimberley 1989; Weaver and Agle 2002) that stresses the idea that individuals occupy positions in various social structures and that these positions incorporate role or behavioral expectations. Groups expect certain forms of role performance from their members. If the individual internalizes these role expectations, they become part of a person’s identity as a member of a specific group. This means that if the subjective norm towards SR products is internalized by the individual, it will also affect the attitude towards SR products. Therefore, we hypothesize:

H3

A positive subjective norm to buy SR products encourages a positive attitude towards SR products

Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior assumes that religion is one of the background factors that may influence the consumers attitude and subjective norm (Ajzen and Fishbein 2005). Religiosity can be defined as an orienting worldview that is expressed in beliefs, narratives, symbols, and practices of worship (Peterson 2001). Religiosity is an important source of personal values (Fry et al. 2011; Fry and Slocum 2008; Parboteeah et al. 2009; Ramasamy et al. 2010). For example, a conception of God as just and merciful may generate corresponding values. Likewise, the theological conception of human beings as having been created equal may generate moral standards such as solidarity and fairness. As values serve as a base for the formation of attitudes (Ajzen and Fishbein 1980; Dickson and Littrell 1996; Hill 1990), religiosity will also likely influence attitudes towards pro-social behavior such as buying SR products. Many religions express values such as stewardship, charity, clemency, and righteousness. For example, in Islam, one of the core values in economic life is justice (Ahmed 1995; Abeng 1997). A Muslim has to be benevolent by taking into consideration the needs and interests of other people, by providing help free of charge if necessary, and by supporting activities that are good and beneficial to the whole of society. This also includes the protection of the environment (Hasan 2001). As vicegerents of Allah, Muslims are encouraged to utilize the natural resources made available to them in a socially responsible manner. Because of the importance of social values in most religions, it is usually found that religious people tend to be—or at least perceive themselves as—pro-social and helpful (see Batson et al. 1993). Because of this pro-social self-perception, it is likely that they develop a positive attitude towards products that aim at social goals. According to symbolic interactionism theory, the degree of internalization of standards derived from the religious community will depend on the salience of the religious identity (Weaver and Agle 2002). The more salient this identity, the greater the likelihood that a person’s behavior will be guided by the expectations associated with that identity. Failure to act in a manner that is consistent with a highly salient religious identity is likely to generate strong levels of cognitive dissonance and emotional discomfort (Fry 2003). Based on this, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4

Religiosity has a positive effect on the attitude towards SR products

Furthermore, in the model of Ajzen and Fishbein (2005), religiosity may also influence the subjective norm of individuals. Since the religious values and concrete behavioral norms of a religious community will affect the attitude and behavior of other people in the religious community to which the individual belongs, it is likely that they will also influence the social norm of those people who are important to the individual religious person. If the subjective norm of the religious community is internalized by the individual, it will affect his or her attitude towards SR products and in this way indirectly foster the demand for SR products. But even if the subjective norm is not internalized by a positive attitude towards SR products, it will likely have a direct effect on the demand for SR products as the individual will be pressured to act in accordance to the expectations of fellow believers. The more intensely the individual participates in the religious community, the more likely the social norm in the religious community will affect the subjective norm of the individual. This leads to the fifth hypothesis:

H5

Religiosity has a positive effect on the subjective norm towards SR products

Besides the influences of religiosity on attitude towards SR products and subjective norm, it may also exert a direct influence on the purchase of SR products. In particular, literature on the relationship between religiosity and pro-social behavior has also noted the possibility of hypocrisy. Research on the psychology of religion (Spilka et al. 2003) has indicated that (intrinsically) religious people only appear to be helpful and pro-social, but that in reality they are preoccupied with their positive self-perception rather than with the needs of others (Batson et al. 1993). Although religious people claim to be helpful, this claim is not reflected in their behavior (Batson and Flory 1990). This would suggest that religious people may be moral hypocrites rather than altruists: they pretend to have social attitudes but their behavior does not confirm such a perception. This paradox contradicts our expectation, as Christianity (as well as other Abrahamic religions) teaches that performing actions rather than forms or words matter. This is, for example, expressed by the parable of the good Samaritan (Luc. 10: 25–37) and the parable of the two sons (Matt. 21: 28–31). Both parables reject hypocrisy and state that only people who actually help others do the will of God. This begs the question why religious persons are more inclined to hypocrisy than non-religious persons. One possible explanation is overpowered integrity (Batson and Thompson 2001). According to this theory, religious people may initially intend to be moral (as required by their religion), but refrain from acting if the costs of moral behavior become evident and if self-interested motives appear to be stronger. Another explanation distinguishes horizontal and vertical faith and argues that religions stimulating vertical faith make people develop affirmative views on helping others due to its centrality to their religious teachings, but do not necessarily increase pro-social behavior along with the increase in altruistic belief (Ji et al. 2006). Religious orthodoxy may stimulate people to concentrate on their relationship with God while deflecting them from building compassionate ties with others and the community. For orthodox Christians, this discrepancy may be fueled by the doctrine of grace: although this doctrine calls Christians to do good to others as an expression of their gratefulness to God because of his grace to them, it also states that their salvation does not depend on doing good works. This might induce Orthodox Protestants to separate the private, religious domain from the economic domain (Van den Belt and Moret 2010). Put in the context of the theory of planned behavior, religious hypocrisy would imply that religiosity stimulates a positive attitude towards SR products, but does not influence behavior, and therefore increases the gap between attitude and behavior. This finding that religiosity increases the gap between attitude and behavior is confirmed by many studies into various forms of pro-social behavior (Batson and Flory 1990; Batson et al. 1999; Ji et al. 2006; Hood et al. 2009). Whereas positive attitude normally stimulates behavior according to the theory of planned behavior, religious hypocrisy would imply that a negative correction is needed in the case of religiosity. Therefore, we posit the following hypothesis:

H6

Religiosity has a negative effect on the demand for SR products, over and above the positive effects of the attitude and subjective norm towards SR products

Combination of H1–H6 implies that the model allows various possibilities of how religiosity may foster the attitude towards SR products without changing the demand for SR products (see Table 1). First, if H4 is confirmed, but all other hypotheses are not confirmed, religiosity will have a positive influence on the attitude towards SR products without changing the demand for SR products. Then religiosity will increase the gap between attitude and behavior indicating hypocrisy. Second, if both H3, H4, and H5 are supported, but all other hypotheses are not, then religiosity will not only increase the attitude towards SR behavior directly, but also indirectly through raising the subjective norm. But since both attitude and social norm do not affect the demand for SR products, the demand for SR products will not be affected by religiosity. Hence, again the gap between attitude and the demand of SR products will increase with religiosity. Third, even if H1–H5 are all confirmed, religiosity does not necessarily increase the demand for SR products, if the positive effects of religiosity on the demand for SR products through attitude and subjective norm are corrected by a direct negative effect (hypothesis 6). In that case, a rise in religiosity will not increase the demand for SR products as much as the attitude towards SR products, and therefore, the gap between attitude and the demand for SR products will also increase.

Methodology

Data Collection

The empirical research is based on a survey developed by Gielissen (2010). Data were collected using a questionnaire filled out by a large sample of Dutch consumers. Data collection was done by GfK panel services in The Netherlands (www.gfk.nl). GfK uses its own ‘continuous panels’: large representative samples of consumers that regularly fill out questionnaires. For this study, use was made of the ‘GfK Consumer Jury,’ an internet panel consisting of Dutch consumers. Advantages in using this panel include a fast response, a high response rate, a representative sample, and the fact that the researcher and the respondent have no personal contact, which reduces the likelihood of respondents giving socially desirable answers.

As a pre-test of the questionnaire, 25 participants were asked to fill out the questionnaire and to give comments (e.g., whether they judged questions to be understandable and, if not, why). This allowed the researchers to assess how the questions were interpreted by these respondents. Based on their responses, the questionnaire has been improved on several points.

The questionnaire was put online by GfK and 1400 consumers, and members of the Consumer Jury panel were invited to fill out the questionnaire. After 1 week, 1030 questionnaires were returned—a response rate of 73.5 %.Footnote 1

Measurement of SR Products

We researched four SR products: fair trade coffee, organic meat, free-range eggs, and fair trade chocolate sprinkles. In order to respect the principle of compatibility, all dependent and independent variables were enquired for each of these products. For each product, we used five categories, referring to the purchase frequency of the SR version in the recent past:Footnote 2 1 = never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = periodically, 4 = often, 5 = always. Reliability analysis using the Cronbach alpha shows that the purchase frequencies of the four SR products are internally consistent. The last column in Table 2 shows that the Cronbach alpha exceeds the lower limit of 0.60 (Cohen et al. 2003; Hair et al. 1998). In the empirical analysis, we therefore tested the hypotheses for the average of the outcomes for the four products.Footnote 3

The buying frequency is thus based on self-reported behavior. The use of such measures has some drawbacks. Discrepancies between self-reported and actual behavior may arise because respondents do not always give accurate reports of their behavior (Olson 1981). Overestimation of desirable behavior by respondents was encountered, for example, by Hadaway et al. (1998) in a study about church visiting. Nevertheless, self-reported behavior is a generally accepted measure of behavior (Bernard 2000), as several studies suggest that self-reported behavior and actual behavior are highly correlated (Fuijii et al. 1985; Gatersleben et al. 2002). Furthermore, we asked respondents for recent behavior in order to reduce the risk of overestimation or forgetting.

Another risk of asking for past behavior is that respondents give socially desirable answers. However, in a study on pro-environmental behavior (a related field), Kaiser et al. (1999) showed that people are only marginally tempted to give socially desirable answers. Furthermore, the likelihood of respondents giving socially desirable answers was reduced by the fact that the survey was set out online with no direct contact between researchers and respondents. Furthermore, respondents knew that their identity would remain confidential. Respondents thus had no reason to present a too favorable picture of themselves.

Respondents were also asked to indicate on a list of eight other SR products which of these they ever have bought (fair trade rice, fair trade sugar, fair trade fruit juice, fair trade thee, fair trade bananas, products from world shop, fair trade clothing, fair trade chocolate). Correlation coefficients were calculated between the number of products from this list that consumers bought and the scores on the 5-point scale for each of the four SR products. The last row in Table 2 shows that the correlations between buying the four SR products and buying other SR products are all positive and significant, implying that the four products may be indicative for buying other SR products as well.

Based on literature, attitude was measured by using three related variables (De Pelsmacker and Janssens 2007): concern about SR products, price acceptability of SR products, and the perceived moral duty to buy the SR product. Each variable was measured by one question per SR product that could be answered on a 5-point Likert scale (for details, see Table 8 in Appendix 1). Reliability analysis using Cronbach alpha shows that the three variables are internally consistent (see last column of Table 2). If we test the reliability of attitude, combining concern, price acceptability, and moral duty for the four SR products, we find a Cronbach alpha of 0.92, which also exceeds the lower limit of 0.60. Based on this, we define the attitude towards SR products as the average of the scores for concern, price acceptability, and the perceived moral duty for the four SR products.

The subjective norm towards SR products was investigated by four questions, one question per type of SR product. For each of the four SR products, we used the same question used by Robinson and Smith (2002) and employ a 5-point Likert scale to measure the response to the statement: ‘People that are important to me, appreciate it if people buy fair trade coffee/organic meat/free-range eggs/fair trade chocolate sprinkles.’ Although the use of one question is unconventional, Bergkvist and Rossiter (2007) show that there is no difference in the predictive validity of multiple-item and single-item measures, and recommend the use of single-item measures. Robinson and Smith (2002) and Welsch and Kühling (2009) also use one question for measuring subjective norm. Reliability analysis using the Cronbach alpha shows that the subjective norms of the four SR products are internally consistent (see last column of Table 2). Based on this, subjective norm was calculated as the average of the four questions for subjective norm per type of product.

In Table 2, the outcomes of the survey are reported for the SR-related questions. The share of consumers buying SR products instead of the non-SR product is relatively small for fair trade coffee, organic meat, and chocolate sprinkles, which is in line with the small market shares of these products in the Netherlands (about 4–6 %; see OneWorld 2011). For free-range eggs, the share of SR products is more substantial. With respect to the attitude towards SR products, the respondents on average think that it is a positive thing that people buy SR products (3.0 is neutral; see Table 8 in Appendix 1). They are, however, on average neutral about whether people should buy SR products, although in the case of organic meat and free-range eggs, there is a slight tendency to support such a moral duty. Respondents tend to agree that SR products are fairly priced. They do not believe, on average, that relevant others approve or disapprove of buying SR products.

Measurement of religiosity

Existing research tends to conceptualize and measure religiosity in terms of affiliation (i.e., Barro 1999; Brown and Taylor 2007), church membership (i.e., Lipford and Tollison 2003), behavioral terms such as church attendance (i.e., Agle and Van Buren 1999), religious motivation (i.e., Clark and Dawson 1996), or general indications of religious commitments (i.e., Albaum and Peterson 2006).

In our research, religiosity was measured by three questions regarding affiliation and religious behavior. We distinguish between four different types of affiliations: non-religious,Footnote 4 Catholic, Orthodox Protestant (e.g., Calvinists and Evangelicals) and Other Protestant. As religious affiliation does not necessary imply that a person practices his or her religion, we also use two measures for religious behavior. Religious practice is typically seen as an indicator of how much value individuals place on religion, and Parboteeah et al. (2004) have even argued that the behavioral measure is one of the best indicators of the degree of religiosity of individuals. Cornwall et al. (1986) suggests that for the behavioral dimension in the ‘‘acting out’’ aspect of religion, church attendance and praying are prominent. Therefore, we included questions on church attendance and intensity of praying or meditation. The Cronbach alpha of the two dimensions of religious behavior equals 0.76 which exceed the lower limit of 0.60. Also Mazereeuw et al. (2014) found for the Netherlands that their five measures of the behavioral aspect of the religiosity of the respondents (measured by attendance of religious services, participation in other activities of the religious community, and time spent on private prayer, work-related prayer, and meditation) strongly correlate with each other. Based on these results, we construct religious behavior as an average of the two measures.

Affiliation and the intensity of religious behavior only capture a subset of possible indicators of religiosity. Most researchers do agree that religiosity cannot be conceived as a single, all-compassing phenomenon (De Jong et al. 1976). Other variables that may be used to measure religiosity do not only consider the behavioral, but also the cognitive and motivational aspects of religiosity (Parboteeah et al. 2007). However, in similar research on the relationship between religiosity and corporate social responsibility in the Netherlands, Mazereeuw et al. (2014) found a positive and very significant correlation between the cognitive, affective, and behavioral aspects of religiosity. They measured the cognitive dimension with five questions and the affective dimension by 14 questionsFootnote 5 and found that the cognitive, (intrinsic) affective, and behavioral dimensions of religiosity all load on one factor. For this reason, we assume that our measurement of the behavioral dimension of religiosity provides an acceptable approximation of the cognitive and affective aspects of religiosity in the Netherlands.

Table 3 shows that the affiliations of the respondents in our sample fairly represent the shares of non-religious and three types of religious groups in the Netherlands in 2012.Footnote 6 The intensity of religious behavior is highest for people with an Orthodox Protestant affiliation.

Control Variables

Besides religiosity, other socio-demographic variables may also affect attitude, subjective norm, or buying behavior in relation to SR products. Socio-demographic variables that have been found to affect the consumption of socially responsible products are income, education, age, and gender. Households with a higher income are generally faced with lower budget restrictions. Estimating consumer demand for eco-labeled apples, Blend and Van Ravenswaay (1998) showed that US households with a higher income reported a significantly greater willingness to buy eco-labeled apples. For the UK, Batley et al. (2001) showed a significant positive relationship between income and willingness to pay a price premium for green electricity. A similar effect was found by Ivanova (2005) for consumers’ willingness to pay for “green electricity” (electricity from renewable sources) in Queensland. Besides income, education may foster the behavior towards SR products, as higher educated consumers have more knowledge about social and environmental problems. For Belgium, De Pelsmacker et al. (2005) found that people with a high level of education were more inclined to buy fair trade coffee. A similar effect was found by Ivanova (2005) for Queensland consumers’ willingness to pay for green electricity. However, in an empirical study in The Netherlands, income and education did not significantly explain the demand for SR products or willingness to pay (Beckers et al. 2004). Furthermore, empirical research shows that age and gender may influence the purchase of SR products. Jensen et al. (2002) estimated that age has a significant positive impact on the likelihood of participating in the market for certified hardwood, because age raises the willingness to pay a price premium. A positive age effect on willingness to pay a price premium for products that were produced in an environmentally friendly way was also found by Beckers et al. (2004). However, the results of this study are contradicted by a study on organic food by Millock et al. (2002). In this study, (female) gender was found to have a significant positive impact on the demand for SR products, but age was found to have a significant negative effect, because it reduced the willingness to pay a price premium for organic food. A negative age effect is also seen in the study of Ivanova (2005) on consumers’ willingness to pay for green electricity. A positive gender effect was also detected by Loureiro et al. (2002) on the demand for eco-labeled apples and by Beckers et al. (2004).

Table 4 shows that the distributions of age and gender in the sample are fairly representative for The Netherlands. With regard to education and net monthly income, respondents with a low level of education and low income are overrepresented and respondents with a high level of education and high income are underrepresented in the sample. But since all levels are sufficiently represented, this does not affect testing the influence of these variables on the demand for SR products. Analysis of the non-response shows that there are no significant differences in gender and level of education between the 1030 respondents and the 370 non-respondents (χ 2 values are 0.03 and 2.89 with critical values of 3.84 and 5.99 for α = 0.05, respectively). Furthermore, the respondents are not significantly older or younger than the non-respondents (using α = 0.05).

Estimation Results

In this section, we present the empirical analyses for the relationships in the conceptual framework. First, we present the results of bivariate correlation analysis. Next, we present the results of a structural equation model (SEM). SEM enables us to take into account the covariations between various dependent and independent variables and test the nomological validity and therefore not only the validity of the various hypothesized relationships separately, but also the validity of the connectedness of the relationships, i.e., the structure of the model.

Before performing statistical analysis, we tested for heteroskedasticity and outliers. Cross plots showed no heteroskedasticity, whereas box plots indicated no problematic outliers. Given the large sample, multivariate normality should not pose serious problems. Furthermore, although we use Likert scales for various variables, the factors are composed from several variables for the four products and therefore we treat these scales as continuous variables.

A final methodological issue is the possibility of simultaneity. The most important point to note here is that from a theoretical point of view, one can exclude reverse causality from buying socially responsible (SR) products, SR attitude, and SR subjective norm on religiosity, because the religiosity of person is a very structural dimension of one’s identity that will not change as a result of SR behavior. That means that reverse causality is not a problem for hypotheses 4–6 relating to the influence of religiosity on SR attitude, subjective norm, and buying behavior. Also reverse causality from buying SR products and SR attitude on SR subjective norm (relating to hypotheses 2–3) is unlikely from a theoretical point of view, because the subjective norm is the norm of other people in the social environment of the respondent and it is unlikely that it will change by the SR behavior of the individual respondent. There might only be a serious reverse causality in hypothesis 1, as buying SR products might reversely impact on SR attitude of the respondent. For example, whereas a positive attitude towards SR products will stimulate purchases of SR products, these purchases may also inversely lead to a positive attitude. Non-buyers have no experience with SR products and are therefore less likely to report a positive attitude. We will therefore have to consider the possibility of reverse causation from buying behavior on attitude.

Bivariate Correlation Analysis

In Table 5, the results of the bivariate correlation analysis are reported. The table shows that the SR-related variables are highly correlated. Interestingly, we also find some significant relationships between religiosity and the SR products-related variables. First, the intensity of religious behavior is significantly positively related to the demand for SR products and a favorable attitude and subjective norm towards SR products. This is also reflected by the negative relationship between non-religiosity and SR products. People stating that they are not religious report a significantly lower attitude, subjective norm, and demand for SR products. If we consider the various religious affiliations, it turns out that there is substantial variance per affiliation. Whereas people with an Orthodox Protestant affiliation have a significantly lower demand for SR products and weaker attitude towards SR products, people with an ‘Other Protestant’ affiliation have a significantly stronger attitude towards SR products and subjective norm, whereas people with a Catholic affiliation have an intermediate position. Overall, there is almost no sign of hypocrisy of religious people with regard to SR products, since the correlations between the various dimensions of religiosity and attitude do not differ very much from the correlations between religiosity and the demand for SR products. Only for ‘Other Protestants,’ the significant positive correlation between religious affiliation and attitude is not matched by a similar positive relationship between their affiliation and the demand for SR products.

Structural Equation Model

The bivariate correlation analysis only provides a first crude indication of the relationships between religiosity and SR products. In this section, we use SEM to further test the model. Besides including the structural paths, we also include the various control variables in the model and use maximum likelihood as an estimation technique. The estimation results are reported in Fig. 2.

The model fits the data well. The Chi-square value is insignificant. Also the comparative fit index (CFI) and the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) suggest a very good model fit. For the CFI, values larger than 0.95 are generally seen as confirming a good model fit (Byrne 2010). The same is true for the TLI, an index that not only takes sample size into account but also includes a penalty function for overparametrization by incorporating the degrees of freedom. Good model fit is also confirmed by the RMSEA, because it has a value smaller than 0.06 (MacCallum et al. 1996; Hu and Bentler 1999) and by the standardized root of mean square residual (SRMR) value (values below 0.05 indicate a good model fit).

Figure 2 shows that hypotheses 1–3 expressing the structural relationships between attitude, subjective norm, and the purchase of SR products are all supported by the data. The attitude towards SR products has a strong and very significant effect on the demand for SR products, which is in line with the theory of planned behavior. The direct influence of subjective norm on the demand for SR products is also significant, but relatively small compared to the influence of attitude towards SR products. But on top of the direct effect, the subjective norm also exerts an indirect influence on the demand for SR products by stimulating a positive attitude towards SR products. In order to check for reverse causation from the consumption of SR products on the attitude towards buying SR products, we inspected the modification indices of the model. They show no indication that including a causal link from buying behavior on attitude would significantly increase the model fit. This indicates that the attitude towards buying SR product is exogenous to buying SR products and, hence, we conclude that reverse causation from buying behavior on attitude to buying SR products is not present.

The variables that are of most interest to us concern the influence of religiosity (depicted by the dashed arrows). Since we research the effects of religiosity on SR behavior, we take the non-religious respondents as reference group. That means that the estimation results for all religious affiliations should be interpreted in comparison to the non-religious group.

We find that the intensity of religious behavior fosters a positive attitude towards SR products. This finding supports hypothesis 4 that religiosity strengthens a positive attitude towards SR products. But hypothesis 4 does not hold for all affiliations, as we find a significant negative effect of the Orthodox Protestant affiliation. The other religious affiliations were found to be highly insignificant and were therefore dropped.

Religious behavior also stimulates a positive subjective norm towards SR products. As Table 3 shows that the church attendance and intensity of praying/mediation is lowest for non-religious persons, the positive influence of religious behavior on subjective norm implies that the social norm to buy SR products is stronger for religious persons than for non-religious persons. These findings provide support for hypothesis 5 that religiosity strengthens a positive subjective norm towards SR products.

For the demand for SR products, the intensity of religious behavior and the dummies for the three religious affiliations were all highly insignificant and therefore dropped. Hence, hypothesis 6 is not supported.

In order to analyze the total net impact of religiosity on the attitude towards SR products and the demand for SR products, we calculate the total effects of the religiosity variables on the attitude towards, and demand for, SR products (see Table 6). The SEM estimation technique allows us to decompose the total effects in direct and indirect effects on the attitude towards SR products and the demand for SR products, and to calculate the significance of the direct, indirect and total effects. The total effect on the attitude towards SR products is defined as the sum of the direct effect on the attitude towards SR products and the indirect effects mediated by the subjective norm towards SR products. The total effect on the demand for SR products is defined as the sum of the direct effect on the demand for SR products, and the indirect effects mediated by the attitude and subjective norm towards SR products.

Table 6 shows that the intensity of religious behavior significantly enforces a positive attitude towards SR products through a combination of a direct effect and an indirect effect mediated by subjective norm. When we look more closely to the various affiliations, this overall finding is complemented by negative effects on the attitude towards SR products from Orthodox Protestant affiliation. Since both the attitude and the subjective norm raise the demand for SR products, we find very similar indirect effects for the demand for SR products: overall, religious behavior significantly increases the demand for SR products, but this effect is weakened for people with Orthodox Protestant affiliation.

For the other socio-demographic variables (depicted by the dotted arrows in Fig. 2), we find that the attitude towards products depends positively on educational level (with low education as reference) and (female) gender (with male gender as reference), whereas high age (with 18–34 years age as reference) enforces the subjective norm towards SR products. No significant effects were found for household income. Consequently, the demand for SR products is indirectly affected by educational level, age, and gender. In addition, educational level and high age also increase buying behavior directly. The last column of Table 6 shows that education, age, and gender all significantly increase the demand for SR products.

Discussion

In this article, we research the influence of several dimensions of religiosity on the demand for SR products in the Netherlands. Based on a survey of four SR products among 997 households, we find support for the theory of planned behavior as an explanation of the demand for SR products. In line with this theory, we find that the demand for SR products depends on the attitude towards SR products (H1) and on the subjective norm towards SR products (H2).

In order to trace the influence of religiosity on the demand for SR products, we tested the influence of two dimensions of religiosity on attitude, subjective norm, and the purchase of SR products: religious behavior and religious affiliation. We controlled for various other socio-demographic variables (income, education, gender, age). Since research on the relationship between religion and pro-social behavior shows that religiosity encourages social attitudes, we expected that the intensity of religiosity fosters the attitude towards SR products. The estimation results indeed support the hypothesis that religiosity encourages a positive attitude towards SR products, both directly (H4) and indirectly through subjective norm (H3 and H5). Only for Orthodox Protestant affiliation, a negative relationship is found between religious affiliation and attitude towards SR products.

The outcomes of the structural equation model also throw more light on the outcomes of the bivariate correlation analysis in Table 4 that attitude, subjective norm, and the demand for SR products are negatively related to non-religious affiliation. As non-religious persons exhibit no religious behavior, the positive influence of religious behavior on attitude and on subjective norm implies that non-religious persons have a weaker attitude and subjective norm than persons with a Catholic or another Protestant affiliation. Furthermore, as both attitude and subjective norm increase the demand for SR products, these results imply that the demand for SR products is also lower for non-religious persons in comparison to persons with a Catholic and Other Protestant affiliation. Finally, the outcome that Orthodox Protestants are found to have a relatively weak attitude towards SR products also explains that their SR demand is comparatively low, as is shown by the bivariate correlation analysis in Table 4.

Based on the theory of planned behavior, one would expect religiosity to stimulate the demand for SR products by encouraging a positive attitude towards them. However, literature on the relationship between religiosity and pro-social behavior indicates that it could also be the case that religiosity improves the attitude towards SR products without affecting behavior. In the theory section, we distinguished three specifications of our model that would imply religious hypocrisy. The estimation results invalidate all these models, as we find empirical support for H1–H5, but not for H6. This implies that we find nothing that supports hypocrisy in the sense that religiosity widens the attitude-behavior gap by stimulating a positive attitude towards SR products without affecting the purchase of SR products. For none of the religious affiliations was such a hypocrisy effect found.

This begs the question what factors make the demand for SR products different from other types of pro-social behaviors for which religious hypocrisy was detected. In our theory section, two explanations were given for religious hypocrisy: overpowered integrity and vertical faith. From Table 7, it can be noted that the first reason, overpowered integrity, does not discriminate non-religious groups from religious groups. For all groups, the attitude and subjective norm to SR products are on average slightly positive to close to neutral (3.0 is neutral; see Table 8 in Appendix 1). None of the four groups sincerely perceives that buying SR products is a moral duty. Therefore, it is not surprising that the demand for SR products is low, given the price differential between SR products and non-SR products. Basically this shows that hypocrisy is not very relevant in the case of SR products, as hypocrisy occurs if actions are absent while people hold significant positive attitudes. The underlying reason might be that the effectiveness of SR products has been subject to various types of criticism, e.g., that it creates overproduction (Singleton 2005); that fair trade is not beneficial for the poorest (Mohan 2010); that it is uncertain whether fair trade is really better for producers than other production standards, such as the Rainforest Alliance and Utz (Kolk 2012); and that is uncertain how much of the extra price premium trickles down to the producer (Booth and Whetstone 2007). This type of criticism may have weakened the attitude towards SR products.

The clearest indication that the low demand for SR products is not explained by religious hypocrisy is the finding for the Orthodox Protestant group. The demand for SR products is lowest for this group, but this is not caused by hypocrisy, but by the relative weak attitude and subjective norm. Actually, the gap between attitude and behavior is relatively low for this group in comparison to other groups. This indicates that also the second reason for religious hypocrisy—that vertical faith leads to a disconnection between an affirmative view on helping others and actual pro-social behavior—is not relevant for SR products. One explanation is that Orthodox Protestant churches do indeed stress a moral duty to help other people, but that the type of help that is recommended mostly concerns direct financial support to (church related) social organizations as a way of solving social problems (Brooks 2004; Scheepers and Te Grotenhuis 2005; Reitsma 2007). Orthodox Protestant persons will therefore be less aware that the moral duty to help other people also extends to consumption of SR products, which indirectly alleviates poverty in third world countries. For the same reason, Orthodox Protestants may have a relatively negative attitude towards organic meat or free-range eggs, because traditional Christian teaching has often not provided much support for the moral duty to safeguard animal welfare (Linzey 2000; Nussbaum 2006; Singer 2009).

Still, one can also argue that there is some truth in the vertical faith explanation of the low demand for SR products by Orthodox Protestants, not in the sense of causing hypocrisy but by diminishing the attitude towards SR products. A well-known explanation is the idea of dispensationalism, belief in the “end of time” and renewal of the earth in eternity (Curry-Roper 1990; Guth et al. 1995). This weakens the appeal of stewardship with regard to social issues and animal life today. Furthermore, Orthodox Protestant (particular Calvinistic) teachings imply a negative conception of human beings (Mazereeuw et al. 2014). A strong awareness of the sinful nature of man may result in a feeling of impotence about doing any good. This may reduce the appeal to the moral duty to do well to others, including adopting responsible consumer behavior. These reasons do not necessarily lead to hypocrisy, but do explain that Orthodox Protestants are less engaged with SR products by weakening the perception of a moral duty to buy SR products.

Policy Implications and Future Research

The theory of planned behavior and the estimation results show that for most consumers, a positive attitude is a necessary requirement for considering buying SR products. The results also show that all groups studied in this paper have a positive but not very strong attitude towards SR products. This indicates that there is still room for enhancing the attitude towards SR products. People need strong positive attitudes to guide their behavior, particularly if they are faced with temptations (such as lower prices for non-SR products than for SR products). In order to stimulate the demand for SR products, suppliers of SR products should therefore try to enforce the attitude towards SR products. For example, sellers of fair trade products should give more (transparent) information on the effectiveness of SR products and show that they are really beneficial for the groups that these products aim to support and do not contribute to overproduction. Communication on how fair trade organizations help small enterprises to improve their business by offering minimum prices that cover the costs of sustainable production and living costs and by providing technical assistance may reduce uncertainty about the effects of SR products. Fair trade organizations also foster long-term contracts to encourage forward planning, reduce the number of intermediaries, and provide credit when requested. In so doing they encourage productivity, competitiveness, and economic independence among small businesses. Sellers of organic meat should point out the difference in animal welfare between animals in the bio-industry and animals raised on organic farms to consumers. They could, for example, cooperate with TV stations of magazines in making documentaries about the differences in animal welfare of the production of SR products and non-SR products. This is likely to enhance the perceived effectiveness of buying SR products and will then also increase the concern about SR products, the perception of a moral duty to buy SR products, and the acceptability of the higher price. Once individuals develop stronger positive attitudes towards SR products, they will also affect subjective norms in the communities in which these individuals participate and encourage other members of their group to buy SR products.

Furthermore, for marketing purposes, the results suggest that (temporarily) lowering the price of SR products is not advisable as the results of the survey show that most consumers think prices of SR products are fair. Moreover, lowering prices may fuel doubts about the effectiveness of the SR product, as clients will wonder how coffee farmers still benefit if consumers buy fair trade coffee at a discount price. We therefore doubt the effectiveness of trying to stimulate the demand for SR products by lowering the prices. Instead, sellers could better stimulate the demand for SR product by trying to convince shop owners to put SR products in good locations in the store (e.g., not on the bottom shelf).

Third, the identification of other socio-demographic factors that increase SR demand may help the marketing and communication departments of those companies that sell SR products direct their efforts to the market segments of present and potential buyers. The market segment of present buyers often needs supportive arguments and reinforcement to continue and maintain their repeat buying behavior (loyalty). The segment comprising potential buyers needs arguments that will change their behavior and encourage them to switch to buying SR products. They need to be convinced and persuaded that switching will contribute to their own and to society’s benefit by addressing the societal issues that SR products help to remedy. Basing their approach on our findings, sellers wishing to target certain groups in society may be recommended to focus on higher educated, older, and female consumers.

Fourth, we found that persons with an Orthodox Protestants affiliation lack behind in attitude and demand for SR products and gave certain theological reasons for this finding. However, it is not up to suppliers of SR products to try changing the attitude and demand for SR products of this group by theological arguments, as this might lead to an undesirable mixing of commercial and theological motives. But our results might support theologians or other members of the Orthodox Protestant affiliation, who want a debate on SR products within this religious community, as there may be good moral arguments for buying SR products, also from an Orthodox Protestants perspective. First, although current financial support for (church related) social projects in developing countries might be very useful, the consumption of fair trade products provides a good complement to this financial support as social projects on education and health care will only reach their full development potential if the market conditions for small businesses in developing countries also improve. Second, with regard to organic meat and free-range eggs, theologians may refer to Biblical teachings (which, in Orthodox Protestantism, is the most important source of church teachings) to show that in Scripture, animals exist alongside human beings within the covenant relationship between God and creation (Gen. 1: 29–30; Gen. 9: 9) and that human beings have a responsibility to respect animal life and to take care of animals (see, for example, Ex. 23: 4–5; Deut. 5: 13–14; Deut. 22: 6–7; Deut. 25: 4; Ez. 34: 2–4). Third, the negative perception of human inability to do well may be confronted with the personal life of John Calvin, the founding father of Calvinism, who was anything but passive in taking responsibility for social issues. In Calvin’s view, bringing material help to the poor was not enough; it was also necessary to provide them with the means to emerge from their situation through remunerative work (Bieler 2005). This very neatly fits fair trade’s aim of making the work of farmers in developing countries more rewarding. Therefore, both the Bible and traditional Calvinist teaching provide important sources that could make Calvinists more aware of their social responsibility and stimulate a positive attitude towards SR products.

Limitations and Future Research

Our study is characterized by several limitations, all of which provide avenues for future research.

First, since the data are taken from a cross-sectional survey, causality cannot be tested by making use of time lags. Although we can exclude reverse causality from SR products on religiosity on theoretical grounds, reverse causality from the demand for SR products on attitude towards SR products is possible. We checked the modification indices of the SEM model on this point and found no indication of reverse causality. Furthermore, we also estimated a reduced-form equation relating the difference between attitude towards SR products and buying behavior to the religion variables and other socio-demographic variables only, which provides another test on the hypocrisy thesis in which reverse causality is surely not a problem, and again found no support for the hypocrisy thesis (see Table 9 Appendix 2). But in future research, panel analysis could be used to further test the causal relationships in the full, structural, model.

Another limitation is that the subjective norm is measured by one question per type of good. Although this methodology is not uncommon in research into SR products (Robinson and Smith 2002; Bergkvist and Rossiter 2007; Welsch and Kühling 2009) and Cronbach alpha showed that this measure is reliable for the four SR products in our model, the reliability of the measurement of subjective norm could be further improved by using more questions. For example, Vermeir and Verbeke (2006) used two questions to measure social norm based on the respondents’ agreement with the statements “My family/friends/partner think(s) that I should eat/buy sustainable dairy products” and “Government/doctors and nutritionists/the food industry stimulate(s) me to eat/buy sustainable dairy products.” We expect, however, that the main result of our empirical analysis—no support of religiosity hypocrisy regarding SR products—will not be affected. In Appendix 2, we present an alternative model in which the subjective norm was left out, providing a direct test of the total influence of religiosity on attitude and the demand for SR products. The results are very similar to the results of our main model and the conclusions do not change.

Third, in future research, study of the relationship between religiosity and SR products should be extended to other countries. Other religions, such as Islam and Buddhism, were not well represented in our sample and therefore dropped. As argued by Parboteeah et al. (2009), most major religions around the world have similar views on work. Whether this also holds for the attitudes towards SR products and SR consumption behavior requires further research. Comparing different religions in relation to SR attitudes and behavior requires the gathering of international data, carefully controlling for cultural differences that may easily be confused with the influence of religiosity.

Finally, qualitative research could deepen our knowledge of how religious people understand the relationship between their religion and the responsibilities towards others that are implied by sacred texts and social responsibilities in their consumption behavior.

Notes

The sample includes six very small religious groups (Jewish, Islamic, Buddhist, Hinduism, Humanist, other). Since the numbers of people of these groups are too small to be treated separately in a statistically satisfactory way, we decided to drop this group from the sample. As a result, the sample used in the regression analysis is 997.

The ‘recent past’ is defined in the questionnaire as ‘during the past 6 months’.

Hence, if the respondent filled in option 1 (not buying) for fair trade coffee, option 2 for organic meat (sometimes buying), option 3 for free-range eggs (periodically buying) and option 2 for fair trade chocolate sprinkles, the score for the average outcome becomes (1 + 2 + 3 + 2)/4 = 2.

This group consists of atheist and agnostic people. In the Netherlands, slightly more people are agnostic rather than atheist. Agnostic people say that they do not know whether God exists.

The outcomes for church attendance are also in line with national statistics. For Catholics, the recent report of the Dutch Bureau of Statistics reports that in 2013 82 % of Catholic people hardly or not at all attend church (which is 77 % in our survey), 7 % only once a month (10 % in our survey) and 11 % more frequently than once a month (13 % in our survey) (CBS, De religieuze kaart van Nederland 2010–2013). For the Protestant groups, the CBS uses a different classification so that their outcomes cannot be compared with our outcomes.

References

Abeng, T. (1997). Business ethics in Islamic context: perspective of a Muslim business leader. Business Ethics Quarterly, 7(3), 47–54.

Agle, B. R., & Van Buren, H. J, I. I. I. (1999). God and mammon: The modern relationship. Business Ethics Quarterly, 9(4), 563–582.

Ahmed, M. (1995). Business ethics in Islam. Islamabad: The International Institute of Islamic Thought.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 5, 179–211.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (2005). The influence of attitudes on behavior. In D. Albarracin, B. T. Johnson, & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), The handbook of attitudes (pp. 173–221). Mawah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Albaum, G., & Peterson, R. A. (2006). Ethical attitudes of future business leaders: Do they vary by gender and religiosity? Business and Society, 45(3), 300–321.

Allport, G. W., & Ross, J. M. (1967). Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5(4), 432–443.

Auger, P., Burke, P., Devinney, T. M., & Louviere, J. J. (2003). What will consumers pay for SR product features? Journal of Business Ethics, 42(3), 281–304.

Barro, R. J. (1999). Determinants of democracy. Journal of Political Economy, 107(6), 158–183.

Batley, S. L., Colbourne, D., Fleming, P. D., & Urwin, P. (2001). Citizen versus consumer: Challenges in the UK green power market. Energy Policy, 29, 479–487.

Batson, C. D., & Flory, J. D. (1990). Goal-relevant cognitions associated with helping by individuals high on intrinsic, end religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 29(3), 346–360.

Batson, C. D., Schoenrade, P., & Ventis, W. L. (1993). Religion and the individual: A social-psychological perspective. New York: Oxford University Press.

Batson, C. D., & Thompson, E. R. (2001). Why don’t moral people act morally? Motivational considerations. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10, 54–57.

Batson, C. D., Thompson, E. R., Seuferling, G., Whitney, H., & Strongman, J. A. (1999). Moral hypocrisy: Appearing moral to oneself without being so. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(3), 525–537.

Beckers, T., Harkink, E., Lampert, M., van der Lelij, B., & van Ossenbruggen, R. (2004). Maatschappelijke Waardering van Duurzame Ontwikkeling. RIVM, Report 50013007/2004.

Bennett, R., & Blaney, R. (2002). Social consensus, moral intensity and willingness to pay to address a farm animal welfare issue. Journal of Economic Psychology, 23, 501–520.

Bergkvist, L., & Rossiter, J. R. (2007). The predictive value of multiple-item versus single-item measures of the same constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 44, 175–184.

Bernard, H. (2000). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Biel, A., & Thøgersen, J. (2007). Activation of social norms in social dilemmas: A review of the evidence and reflections on the implications for environmental behavior. Journal of Economic Psychology, 28, 93–112.

Bieler, A. (2005). Calvin’s economic and social thought. Genève: World Alliance of Reformed Churches/World Council of Churches.

Blend, J., & van Ravenswaay, E. (1998). Consumer demand for ecolabeled apples: Survey methods and descriptive results (pp. 98–20). Department of Agricultural Economics, Michigan State University. Staff Paper.

Booth, P., & Whetstone, L. (2007). Half a cheer for fairtrade. Economic Affairs, 27(2), 22–30.

Brooks, A. C. (2004). Faith, secularism and charity. Faith & Economics, 43(Spring), 1–8.

Brown, S., & Taylor, K. (2007). Religion and education: Evidence from the National Child Development Study. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 63(3), 439–460.

Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS. Basic concepts, applications, and programming. New York: Routledge.

Casadesus-Masanell, R., Crooke, M., Reinhardt, F., & Vasishth, V. (2009). Households’ willingness to pay for “green” goods: Evidence from Patagonia’s introduction of organic cotton sportswear. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 18(1), 203–233.

CBS. (2013). Kerkbezoek neemt af. Retrieved from http://www.cbs.nl/nl-NL/menu/themas/vrije-tijd-cultuur/publicaties/artikelen/archief/2013/2013-3929-wm.htm.

CBS. (2014). Average income of households with several characteristics. Retrieved from http://statline.cbs.nl/statweb/.

Clark, J. W., & Dawson, L. E. (1996). Personal religiousness and ethical judgments: An empirical analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(3), 359–372.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression: Correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, New Jersey.

Cornwall, M., Albrecht, S. L., Cunningham, P. H., & Pitcher, B. L. (1986). The dimensions of religiosity: A conceptual model with an empirical test. Review of Religious Research, 27(3), 226–244.

Curry-Roper, J. M. (1990). Contemporary Christian eschatologies and their relation to environmental stewardship. The Professional Geographer, 42(2), 157–169.

De Jong, G. F., Faulkner, J. E., & Warland, R. H. (1976). Dimensions of religiosity reconsidered: Evidence from a cross-cultural study. Social Forces, 54(4), 866–889.

De Pelsmacker, P., Driesen, L., & Rayp, G. (2005). Do consumers care about ethics? Willingness to pay for fair trade coffee. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 39(2), 363–385.

De Pelsmacker, P., & Janssen, W. (2007). A model for fair trade buying behavior: The role of perceived quantity and quality of information and of product-specific attitudes. Journal of Business Ethics, 75(4), 361–380.

Dickson, M. (2001). Utility of no sweat labels for apparel consumers: Profiling label users and predicting their purchases. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 35(1), 96–119.

Dickson, M. A., & Littrell, M. A. (1996). Socially responsible behaviour: Values and attitudes of the alternative trading organisation consumer. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 1(1), 50–69.

Fazio, R. H. (2007). Attitudes as object-evaluation associations of varying strength. Social Cognition, 25(5), 603–637.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA, Don Mills, Ontario: Addison-Wesley.

Fry, L. W. (2003). Toward a theory of spiritual leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 14, 693–727.

Fry, L. W., Hannah, S. T., Noel, M., & Walumbwa, F. O. (2011). Impact of spiritual leadership on unit performance. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(2), 259–270.

Fry, L. W., & Slocum, J. W. (2008). Maximizing the triple bottom line through spiritual leadership. Organizational Dynamics, 37(1), 86–96.

Fuijii, E. T., Hennesy, M., & Mak, J. (1985). An evaluation of the validity and reliability of survey response data on household electricity conservation. Evaluation Review, 9, 93–104.

Gatersleben, B., Steg, L., & Vlek, C. (2002). Measurement and determinants of environmentally significant consumer behavior. Environment and Behavior, 34(3), 335–362.

Gielissen, R. (2010). How consumers make a difference. An inquiry into the nature and causes of buying socially responsible products. Dissertation, Tilburg University.

Gorsuch, R. L., & McPherson, S. E. (1989). Intrinsic/extrinsic measurement: I/E-revised and single-item scales. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 28(3), 348–354.

Guth, J. L., Green, J. C., Kellstedt, L. A., & Smidt, C. E. (1995). Faith and the environment: Religious beliefs and attitudes on environmental policy. American Journal of Political Science, 39(2), 364–382.

Hadaway, K., Marler, P., & Chaves, M. (1998). Overreporting church attendance in America: Evidence that demands the same verdict. Social Forces, 71, 411–430.

Hair, J., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Halman, L., Luikx, R., & Van Zundert, M. (2005). Atlas of European values Leiden. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV.

Hansen, D. E., Vandenberg, B., & Patterson, M. L. (1995). The effects of religious orientation on spontaneous and nonspontaneous helping behaviors. Personality and Individual Differences, 19(1), 101–104.

Hasan, M. K. (2001). Worldview orientation and ethics: A Muslim perspective. In K. A. M. Israil & M. Sadeq AbulHassan (Eds.), Ethics in business and management: Islamic and mainstream approaches (pp. 41–67). London: ASEAN Academic.

Hill, R. J. (1990). Attitudes and Behavior. In M. Rosenberg & R. H. Turner (Eds.), Social psychology: Sociological perspectives (pp. 347–377). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publications.

Hogg, M. A. (2001). A social identity theory of leadership. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5(3), 184–200.

Hood, R. W., Hill, P. C., & Spilka, B. (2009). The psychology of religion: An empirical approach (4th ed.). New York, NY: Guilford.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Ivanova, G. (2005). Queensland consumers’ willingness to pay for electricity from renewable energy sources. Paper presented at the ANZSEE Conference, Massey University, New Zealand.

Jensen, K., Jakus, P., English, B., & Menard, J. (2002). Willingness to pay for environmentally certified hardwood products by tennessee consumers. Study Series No. 01-02. Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Tennessee.

Ji, C. C., Pendergraft, L., & Perry, M. (2006). Religiosity, altruism, and altruistic hypocrisy: Evidence from protestant adolescents. Review of Religious Research, 48(2), 156–178.

Kaiser, F., Wölfing, S., & Fuhrer, U. (1999). Environmental attitude and ecological behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 19, 1–19.

Kolk, A. (2012). Towards a sustainable coffee market: Paradoxes faced by a multinational company. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 19(2), 79–89.

Linzey, A. (2000). Animal gospel. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press.

Lipford, J. W., & Tollison, R. D. (2003). Religious participation and income. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 51(2), 249–260.

Loureiro, M. L., & Lotade, J. (2005). Do fair trade and eco-labels in coffee wake up the consumer conscience? Ecological Economics, 53, 129–138.

Loureiro, M. L., McCluskey, J. J., & Mittelhammer, R. C. (2002). Will consumers pay a premium for eco-labeled apples? Journal of Consumer Affairs, 36(2), 203–219.

MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 51, 201–226.

Mazereeuw, C., Graafland, J. J., & Kaptein, M. (2014). Religiosity, CSR attitudes, and CSR behavior: An empirical study of executives’ religiosity and CSR. Journal of Business Ethics, 123(3), 437–459.

McCluskey, J. J., Durham, C. A., & Horn, B. P. (2009). Consumer preferences for socially responsible production attributes across food products. Agricultural and Resource Economics Review, 38(3), 345–356.

McNichols, C. W., & Zimmerer, T. W. (1985). Situational ethics: An empirical study of differentiators of student attitudes. Journal of Business Ethics, 4(3), 175–180.

Millock, K., Hansen, L. G., Wier, M., & Andersen, L. M. (2002). Willingness to pay for organic foods: A comparison between survey data and panel data from Denmark. Paper presented at the 12th annual EAERE (European Association of Environmental and Resource Economists) Conference, June, Monterey, CA, USA.

Mohan, S. (2010). Fair trade without the froth. London: The Institute of Economic Affairs.

Moon, W., & Balasubramanian, S. (2003). Willingness to pay for non-biotech foods in the U.S. and U.K. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 37(2), 317–339.

Nussbaum, M. (2006). Frontiers of justice. Boston: Harvard University Press.

Olson, M. E. (1981). Consumers attitudes toward energy conservation. Journal of Social Issues, 37, 108–131.

OneWorld. (2011). Fair trade. Goed bezig of niet? Retrieved from http://www.oneworld.nl/lezen/nieuws/fair-trade-goed-bezig-niet.

Parboteeah, K. P., Cullen, J. B., & Lim, L. (2004). Formal volunteering: A cross-national test. Journal of World Business, 39, 431–442.

Parboteeah, K. P., Hoegl, M., & Cullen, J. B. (2007). Ethics and religion: An empirical test of a multidimensional model. Journal of Business Ethics, 80(2), 387–398.

Parboteeah, K. P., Hoegl, M., & Cullen, J. (2009). Religious groups and work values: A focus on Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, and Islam. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 9(1), 51–67.

Peterson, G. R. (2001). Think pieces, religion as orienting worldview. Zygon, 36(1), 5–19.

Ramasamy, B., Yeung, M. C. H., & Au, A. K. M. (2010). Consumer support for corporate social responsibility (CSR): The role of religion and values. Journal of Business Ethics, 91(1), 61–72.

Reitsma, J. (2007). Religiosity and solidarity: Dimensions and relationships disentangled and tested. Ridderkerk: Ridderprint.

Renneboog, L., & Spaenjers, C. (2009). Where angels fear to trade: The role of religion in household finance (pp. 2009–2034). No: CentER Discussion Paper Series.

Robinson, R., & Smith, C. (2002). Psychosocial and demographic variables associated with consumer intention to purchase sustainably produced foods as defined by the Midwest Food Alliance. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 34, 316–325.

Roe, B., Teisl, M., Levy, A., & Russell, M. (2001). US consumers’ willingness to pay for green electricity. Energy Policy, 29, 917–925.

Scheepers, P., & te Grotenhuis, M. (2005). Who cares for the poor in Europe? Micro and macro determinants of fighting poverty in 15 European countries. European Sociological Review, 21(5), 453–465.

Shaw, D., & Shiu, E. (2003). Ethics in consumer choice: A multivariate modelling approach. European Journal of Marketing, 37(10), 1485–1518.

Singer, P. (2009). Animal liberation. The definite classic of the animal movement. New York: Harper Collins Publishers.

Singleton, A. (2005). The poverty of fairtrade. London: Adam Smith Institute.

Spilka, B., Hood, R. W, Jr, Hunsberger, B., & Gorsuch, R. (2003). The psychology of religion: An empirical approach (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Tajfel, H. (1982). Social psychology of intergroup relations. Annual Review of Psychology, 33, 1–39.

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Oxford, England: Blackwell.

Van den Belt, T., & Moret, J. (2010). Management en levenbeschouwing in Nederland. Enschede: Ipskamp Drukkers.

Vermeir, I., & Verbeke, W. (2006). Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the “consumer-attitude behavioural intention” gap. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 19(2), 169–194.

Vitell, A. J., Paolillo, J. G. P., & Singh, J. (2005). Religiosity and consumer ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 57(2), 175–181.

Vitell, A. J., Paolillo, J. G. P., & Singh, J. (2006). The role of money and religiosity in determining consumers’ ethical beliefs. Journal of Business Ethics, 64(2), 117–124.

Vitell, A. J., Singh, J., & Paolillo, J. G. (2007). Consumers’ ethical beliefs: The roles of money, religiosity and attitude toward business. Journal of Business Ethics, 73(4), 369–379.

Weaver, G. R., & Agle, B. R. (2002). Religiosity and ethical behavior in organizations: A symbolic interactionist perspective. Academy of Management Review, 27(1), 77–97.

Welsch, H., & Kühling, J. (2009). Determinants of pro-environmental consumption: The role of reference groups and routine behaviour. Ecological Economics, 69, 166–176.

Wicker, A. W. (1969). Attitudes versus actions: The relationship of verbal and overt behavioral responses to attitude objects. Journal of Social Issues, 25, 41–78.

Wimberley, D. W. (1989). Religion and role-identity: A structural symbolic interactionist conceptualization of religiosity. Sociological Quarterly, 30, 125–142.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

See Table 8.