Abstract

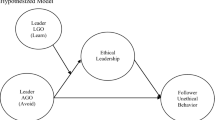

Many business leaders vigorously and single-mindedly pursue bottom-line outcomes with the hope of producing superior results for themselves and their companies. Our study investigated two drawbacks of such leader bottom-line mentality (BLM, i.e., an exclusive focus on bottom-line outcomes at the expense of other priorities). First, based on leaders’ power over followers, we hypothesized that leader BLM promotes unethical pro-leader behaviors (UPLB, i.e., behaviors that are intended to benefit the leader, but violate ethical norms) among followers. Second, based on cognitive dissonance theory, we hypothesized that UPLB, and leader BLM via UPLB, increase turnover intention among employees with a strong moral identity. Data collected from 153 employees of various organizations supported our hypotheses. In particular, leader BLM was positively related to followers’ UPLB. Further, for employees with a stronger (rather than weaker) moral identity: (1) UPLB was positively related to turnover intention; and (2) leader BLM was related to turnover intention via UPLB.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- BLM:

-

Bottom-line mentality

- UPLB:

-

Unethical pro-leader behavior

- UPB:

-

Unethical pro-organizational behavior

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Testing and interpreting interactions in multiple regression. London, UK: Sage.

Ambrose, M. L., Arnaud, A., & Schminke, M. (2008). Individual moral development and ethical climate: The influence of person–organization fit on job attitudes. Journal of Business Ethics, 77(3), 323–333.

Aquino, K., & Becker, T. E. (2005). Lying in negotiations: How individual and situational factors influence the use of neutralization strategies. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(6), 661–679.

Aquino, K., & Freeman, D. (2009). Moral identity in business situations: A social-cognitive framework for understanding moral functioning. In D. Narvaez & D. K. Lapsley (Eds.), Personality, identity, and character: Explorations in moral psychology (pp. 375–395). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Aquino, K., Freeman, D., Reed, A., II, Lim, V. K., & Felps, W. (2009). Testing a social-cognitive model of moral behavior: The interactive influence of situations and moral identity centrality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(1), 123–141.

Aquino, K., McFerran, B., & Laven, M. (2011). Moral identity and the experience of moral elevation in response to acts of uncommon goodness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(4), 703–718.

Aquino, K., & Reed, A., II. (2002). The self-importance of moral identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1423–1440.

Bagozzi, R. P., Yi, Y., & Phillips, L. W. (1991). Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36(3), 421–458.

Basu, T. (2014, March 31). Timeline: A history of GM’s ignition switch defect. NPR. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/2014/03/31/297158876/timeline-a-history-of-gms-ignition-switch-defect.

Baumeister, R. F. (1988). The self. In S. T. F. T. Gilbert (Ed.), The handbook of social psychology (4th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 680–740). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

Berscheid, E., Graziano, W., Monson, T., & Dermer, M. (1976). Outcome dependency: Attention, attribution, and attraction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34(5), 978–989.

Blasi, A. (1984). Moral identity: Its role in moral functioning. In W. Kurtines & J. Gewirtz (Eds.), Morality, moral behaviour, and moral development (pp. 128–139). New York, NY: Wiley.

Bonner, J. M., Greenbaum, R. L., & Quade, M. J. (2017). Employee unethical behavior to shame as an indicator of self-image threat and exemplification as a form of self-image protection: The exacerbating role of supervisor bottom-line mentality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(8), 1203–1221.

Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134.

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. D. (2011). Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1), 3–5.

Callahan, D. (2004). The cheating culture: Why more Americans are doing wrong to get ahead. Orlando, FL: Harcourt.

Chen, M., Chen, C. C., & Sheldon, O. J. (2016). Relaxing moral reasoning to win: How organizational identification relates to unethical pro-organizational behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(8), 1082–1096.

Cialdini, R. B., Petrova, P. K., & Goldstein, N. J. (2004). The hidden costs of organizational dishonesty. MIT Sloan Management Review, 45(3), 67–73.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Craver, R. (2017, April 15). Unattainable sales goals fueled Wells Fargo accounts scandal. Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved from http://www.journalnow.com.

Crawford, E. R., LePine, J. A., & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 834–848.

Dahling, J. J., Whitaker, B. G., & Levy, P. E. (2009). The development and validation of a new Machiavellianism scale. Journal of Management, 35(2), 219–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308318618.

Dawson, J. F. (2014). Moderation in management research: What, why, when, and how. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29(1), 1–19.

Eichenwald, K. (2005). Conspiracy of fools: A true story. New York, NY: Broadway.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Ford, M. T., Heinen, B. A., & Langkamer, K. L. (2007). Work and family satisfaction and conflict: A meta-analysis of cross-domain relations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 57–80.

Greenbaum, R. L., Mawritz, M. B., & Eissa, G. (2012). Bottom-line mentality as an antecedent of social undermining and the moderating roles of core self-evaluations and conscientiousness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(2), 343–359.

Greenbaum, R. L., Mawritz, M. B., Mayer, D. M., & Priesemuth, M. (2013). To act out, to withdraw, or to constructively resist? Employee reactions to supervisor abuse of customers and the moderating role of employee moral identity. Human Relations, 66(7), 925–950.

Greenbaum, R. L., Mawritz, M. B., & Piccolo, R. F. (2015). When leaders fail to “Walk the Talk”: Supervisor undermining and perceptions of leader hypocrisy. Journal of Management, 41(3), 929–956. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312442386.

Griffeth, R. W., Hom, P. W., & Gaertner, S. (2000). A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. Journal of Management, 26(3), 463–488.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Hall, C. (2016, January 2). HealthSouth ex-exec lectures on evils of fraud. The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved from http://www.dallasnews.com/business/columnists/cheryl-hall/20100330-HealthSouth-ex-exec-lectures-on-evils-1307.ece.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hotten, R. (2015, December 10). Volkswagen: The scandal explained. BBC News. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.com/news/business-34324772.

Huang, L., & Paterson, T. A. (2017). Group ethical voice: Influence of ethical leadership and impact on ethical performance. Journal of Management, 43(4), 1157–1184.

Irving, P. G., Coleman, D. F., & Cooper, C. L. (1997). Further assessments of a three-component model of occupational commitment: Generalizability and differences across occupations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(3), 444–452.

Isidore, C. (2015, December 10). Death toll for GM ignition switch: 124. CNN Money. Retrieved from http://money.cnn.com/2015/12/10/news/companies/gm-recall-ignition-switch-death-toll/index.html.

Jansen, E., & Von Glinow, M. A. (1985). Ethical ambivalence and organizational reward systems. Academy of Management Review, 10(4), 814–822.

Jennings, P. L., Mitchell, M. S., & Hannah, S. T. (2015). The moral self: A review and integration of the literature. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(S1), S104–S168.

Kish-Gephart, J. J., Harrison, D. A., & Treviño, L. K. (2010). Bad apples, bad cases, and bad barrels: Meta-analytic evidence about sources of unethical decisions at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(1), 1–31.

Kong, D. T. (2016). The pathway to unethical pro-organizational behavior: Organizational identification as a joint function of work passion and trait mindfulness. Personality and Individual Differences, 93, 86–91.

Lawrence, E. R., & Kacmar, K. M. (2017). Exploring the impact of job insecurity on employees’ unethical behavior. Business Ethics Quarterly, 27(1), 39–70.

Lee, R. T., & Ashforth, B. E. (1996). A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(2), 123–133.

Lee, A., Schwarz, G., Newman, A., & Legood, A. (2017). Investigating when and why psychological entitlement predicts unethical pro-organizational behavior. Journal of Business Ethics.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3456-z.

Lian, H., Huai, M., Farh, J.-L., Huang, J.-C., & Chao, M. M. (2016). Leader UPB and employee unethical conduct: A moral disengagement perspective. In J. Humphreys (Ed.), Proceedings of the seventy-sixth annual meeting of the academy of management. Anaheim, CA: Academy of Management.

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., & Stilwell, D. (1993). A longitudinal study on the early development of leader–member exchanges. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(4), 662–674.

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 151–173.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), 99–128.

Malatesta, R. M. (1995). Understanding the dynamics of organizational and supervisory commitment using a social exchange framework (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Detroit, MI: Wayne State University.

Mandis, S. (2013). What happened to Goldman Sachs: An insider’s story of organizational drift and its unintended consequences. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.

Mawritz, M., Greenbaum, R., Butts, M. M., & Graham, K. A. (2017). I just can’t control myself: A self-regulation perspective on the abuse of deviant employees. Academy of Management Journal, 60(4), 1482–1503.

Mayer, D. M., Aquino, K., Greenbaum, R. L., & Kuenzi, M. (2012). Who displays ethical leadership, and why does it matter? An examination of antecedents and consequences of ethical leadership. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 151–171.

Mayer, D. M., Nurmohamed, S., Treviño, L. K., Shapiro, D. L., & Schminke, M. (2013). Encouraging employees to report unethical conduct internally: It takes a village. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 121(1), 89–103.

McFerran, B., Aquino, K., & Duffy, M. (2010). How personality and moral identity relate to individuals’ ethical ideology. Business Ethics Quarterly, 20(1), 35–56.

Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Herscovitch, L., & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(1), 20–52.

Miao, Q., Newman, A., Yu, J., & Xu, L. (2013). The relationship between ethical leadership and unethical pro-organizational behavior: Linear or curvilinear effects? Journal of Business Ethics, 116(3), 641–653.

Mitchell, M. S., & Ambrose, M. L. (2007). Abusive supervision and workplace deviance and the moderating effects of negative reciprocity beliefs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 1159–1168. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.1159.

Mitchell, M. S., Vogel, R. M., & Folger, R. (2015). Third parties’ reactions to the abusive supervision of coworkers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(4), 1040–1055.

Moser, M. R. (1988). Ethical conflict at work: A critique of the literature and recommendations for future research. Journal of Business Ethics, 7(5), 381–387.

Ordóñez, L. D., Schweitzer, M. E., Galinsky, A. D., & Bazerman, M. H. (2009). Goals gone wild: The systematic side effects of overprescribing goal setting. Academy of Management Perspectives, 23(1), 6–16.

Podsakoff, N. P., LePine, J. A., & LePine, M. A. (2007). Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 438–454.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Raven, B. H., Schwarzwald, J., & Koslowsky, M. (1998). Conceptualizing and measuring a power/interaction model of interpersonal influence. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28(4), 307–332.

Reed, A., II, & Aquino, K. F. (2003). Moral identity and the expanding circle of moral regard toward out-groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(6), 1270–1286.

Reynolds, S. J., & Ceranic, T. L. (2007). The effects of moral judgment and moral identity on moral behavior: An empirical examination of the moral individual. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), 1610–1624.

Romero, S. (2002, July 22). Worldcom’s collapse: The overview. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2002/07/22/us/worldcom-s-collapse-the-overview-worldcom-files-for-bankruptcy-largest-us-case.html.

Rupp, D. E., Shao, R., Thornton, M. A., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2013). Applicants’ and employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: The moderating effects of first-party justice perceptions and moral identity. Personnel Psychology, 66(4), 895–933.

Salancik, G. R., & Pfeffer, J. (1978). A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23(2), 224–253.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Salanova, M. (2007). Efficacy or inefficacy, that’s the question: Burnout and work engagement, and their relationships with efficacy beliefs. Anxiety Stress and Coping, 20(2), 177–196.

Schweitzer, M. E., Ordóñez, L., & Douma, B. (2004). Goal setting as a motivator of unethical behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 47(3), 422–432.

Schwepker, C. H. (1999). The relationship between ethical conflict, organizational commitment and turnover intentions in the salesforce. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 19(1), 43–49.

Shao, R., Aquino, K., & Freeman, D. (2008). Beyond moral reasoning: A review of moral identity research and its implications for business ethics. Business Ethics Quarterly, 18(4), 513–540.

Sims, R. R., & Brinkman, J. (2002). Leaders as moral role models: The case of John Gutfreund at Salomon Brothers. Journal of Business Ethics, 35(4), 327–339.

Sims, R. L., & Keon, T. L. (1997). Ethical work climate as a factor in the development of person-organization fit. Journal of Business Ethics, 16(11), 1095–1105.

Sims, R. L., & Kroeck, K. G. (1994). The influence of ethical fit on employee satisfaction, commitment and turnover. Journal of Business Ethics, 13(12), 939–947.

Skarlicki, D. P., Van Jaarsveld, D. D., & Walker, D. D. (2008). Getting even for customer mistreatment: The role of moral identity in the relationship between customer interpersonal injustice and employee sabotage. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1335–1347.

Sparks, K., Cooper, C., Fried, Y., & Shirom, A. (1997). The effects of hours of work on health: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 70(4), 391–408.

Stets, J. E., & Carter, M. J. (2011). The moral self: Applying identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 74(2), 192–215.

Tepper, B. J., Uhl-Bien, M., Kohut, G. F., Rogelberg, S. G., Lockhart, D. E., & Ensley, M. D. (2006). Subordinates’ resistance and managers’ evaluations of subordinates’ performance. Journal of Management, 32(2), 185–209.

Thau, S., Derfler-Rozin, R., Pitesa, M., Mitchell, M. S., & Pillutla, M. M. (2015). Unethical for the sake of the group: Risk of social exclusion and pro-group unethical behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(1), 98–113.

Tian, Q., & Peterson, D. K. (2016). The effects of ethical pressure and power distance orientation on unethical pro-organizational behavior: The case of earnings management. Business Ethics: A European Review, 25(2), 159–171.

Treviño, L. K., den Nieuwenboer, N. A., & Kish-Gephart, J. J. (2014). (Un) ethical behavior in organizations. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 635–660.

Umphress, E. E., & Bingham, J. B. (2011). When employees do bad things for good reasons: Examining unethical pro-organizational behaviors. Organization Science, 22(3), 621–640.

Umphress, E. E., Bingham, J. B., & Mitchell, M. S. (2010). Unethical behavior in the name of the company: The moderating effect of organizational identification and positive reciprocity beliefs on unethical pro-organizational behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(4), 769–780.

Valentine, S., Hollingworth, D., & Eidsness, B. (2014). Ethics-related selection and reduced ethical conflict as drivers of positive work attitudes: Delivering on employees’ expectations for an ethical workplace. Personnel Review, 43(5), 692–716.

Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1999). The PANAS-X: Manual for the positive and negative affect schedule—Expanded Form. Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa.

Winterich, K. P., Aquino, K., Mittal, V., & Swartz, R. (2013). When moral identity symbolization motivates prosocial behavior: The role of recognition and moral identity internalization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(5), 759–770.

Wolfe, D. M. (1988). Is there integrity in the bottom line: Managing obstacles to executive integrity. In S. Srivastva (Ed.), Executive integrity: The search for high human values in organizational life (pp. 140–171). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Yukl, G., & Falbe, C. M. (1991). Importance of different power sources in downward and lateral relations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(3), 416.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank John Waltman for his helpful comments on different versions of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Salar Mesdaghinia, Anushri Rawat, and Shiva Nadavulakere declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Appendix: Scale Validation Study

Appendix: Scale Validation Study

To examine the dimensionality, reliability, and convergent, discriminant, and criterion validities of our UPLB scale, we conducted two supplemental data collections. The first sample (Validation Sample 1) consisted of 223 employees (mean age = 25 years, SD age = 6.76; 48% female) working at various organizations and jobs who had enrolled in undergraduate and graduate business programs at a university in the Midwestern USA. The employees filled out a survey in exchange for extra credit. We collected the second sample (Validation Sample 2) using Amazon Mechanical Turk, an online crowdsourcing service with a participant pool that is representative of the US population (Buhrmester et al. 2011). This sample consisted of 318 employees working at various organizations and jobs in the USA who filled out our online survey in exchange for money (mean age = 38 years, SD age = 10.47; 51% female).

Dimensionality and Reliability

Exploratory factor analyses (EFA) with UPLB items resulted in one factor explaining 79 and 71% of variance in Samples 1 and 2, respectively. Factor loadings were greater than .63 (.77–.92 in Validation Sample 1; .63–.91 in Validation Sample 2). Cronbach’s α was .95 in Sample 1 and .92 in Sample 2. These results indicate that UPLB is unidimensional and reliable.

Discriminant and Convergent Validities

To examine the discriminant validity of UPLB, we identified a number of other variables that could potentially overlap with UPLB. We used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to compare a model that considered UPLB as distinct from other variables to a series of nested models that combined UPLB with each other variable one at a time. Nested models that showed poorer fit provided evidence that UPLB was distinct from other variables (Bagozzi et al. 1991). Furthermore, as Hair et al. (2006) recommended, we also tested whether the percentage of variance extracted by the UPLB latent factor was greater than the squared correlation between UPLB and other latent factors (or the variance that UPLB explains from other constructs). According to Hair et al. (2006), this approach is more conservative and provides stronger evidence for discriminant validity. We also assessed the convergent validity of UPLB. There were no prior scales for UPLB. However, we examined the correlation between UPLB and other theoretically related constructs such as UPB to examine convergent validity.

Other than our UPLB scale, Validation Sample 1 included a 6-item scale for UPB (Umphress et al. 2010, Study 2), a 7-item LMX scale (Liden et al. 1993), and a 5-item trait amorality scale (a dimension of Machiavellian Personality Scale, Dahling et al. 2009). Further, Validation Sample 2 included a 5-item leader-directed citizenship behavior scale (Malatesta 1995), and a 6-item leader-directed deviant behavior scale (Mitchell and Ambrose 2007). We expected UPLB to be strongly correlated with, yet distinguishable from UPB from which UPLB was derived. That is because UPLB and UPB include similar behaviors, but have different targets (supervisor vs. organization). We also distinguished UPLB from LMX to show that UPLB is not merely a regular component of the exchange relationship between leaders and followers. In addition, we expected UPLB, which is influenced by the situation, to be positively correlated with, yet distinguishable from a stable amoral personality. UPLB should also be distinguishable from citizenship behaviors which seek to benefit the supervisor in ethical ways. Finally, we expected UPLB to be positively correlated with, yet distinguishable from supervisor-targeted deviance. Both of these are unethical behaviors and, therefore, might have some common causes. However, unlike UPLB, supervisor-targeted deviance involves unethical behaviors against the supervisor. Empirically distinguishing these two variables would refute the view that all unethical behaviors are similar and indistinguishable.

First, we applied the procedure outlined above to the variables included in Validation Sample 1, namely UPLB, UPB, LMX, and trait amorality. A CFA that modeled each variable as a separate factor resulted in a good fit (CFI = .92; RMSEA = .08; SRMR = .06). The fit dropped significantly (by at least Δχ2 (3) = 362.55, p < .001) when we combined UPLB with any other factor. Finally, the average variance extracted by the UPLB factor (.76) was greater than the squared correlations between UPLB and any other factor (.03–.49). These results provide evidence that UPLB is distinct from UPB, LMX, and trait amorality. Table 5 shows the correlation between UPLB and other factors. As expected, the UPLB factor had a strong positive correlation with the UPB (r = .70) and amorality (r = .47) factors, but not to the extent that makes it indistinguishable from them.

Next, we repeated the same procedure with variables included in Validation Sample 2, namely UPLB, supervisor-directed citizenship behavior, and supervisor-directed deviance. A CFA that modeled each variable as a separate factor resulted in a good fit (CFI = .92; RMSEA = .08; SRMR = .06). The fit dropped significantly (by at least Δχ2 (2) = 731.25, p < .001) when we combined UPLB with any other factor. Finally, the average variance extracted by the UPLB factor (.66) was greater than squared correlations between UPLB and any other factor (.01–.07). These results provide evidence that UPLB is distinct from supervisor-directed citizenship behavior and supervisor-directed deviance. Table 6 shows the correlation between UPLB and other factors. As expected, the UPLB factor was positively correlated with the supervisor-directed deviance factor (r = .26). Taken together, the two validation samples provided evidence on the convergent and discriminant validities of UPLB.

Criterion Validity

To evaluate criterion validity of UPLB, participants in Validation Sample 2 were asked to rate their guilt and fear over the past 30 days each using six items from PANAS-X (Watson and Clark 1999). They were also asked to rate their cynicism, a dimension of burnout, using four items that measured lack of enthusiasm and meaningfulness in job (Schaufeli and Salanova 2007). Although there are no prior data on the relationship between UPLB and these variables, as an unethical behavior, UPLB can lead to guilt (Umphress and Bingham 2011). Also, engagement in UPLB carries the risk of being caught, punished, or fired, all of which instill fear in employees. Furthermore, unethical behaviors can reduce job meaningfulness and contribute to cynicism, which involves indifference toward one’s job. As Table 7 shows, UPLB was significantly correlated with all of these variables in the predicted directions. This provides evidence for criterion validity of UPLB.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mesdaghinia, S., Rawat, A. & Nadavulakere, S. Why Moral Followers Quit: Examining the Role of Leader Bottom-Line Mentality and Unethical Pro-Leader Behavior. J Bus Ethics 159, 491–505 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3812-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3812-7