Abstract

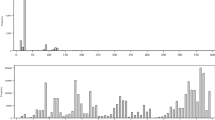

Corrupt politicians have to a surprisingly great extent been found to go unpunished by the electorate. These findings are, however, drawn from case studies on a limited number of countries. This study, on the contrary, is based on a unique dataset from 215 parliamentary election campaigns in 32 European countries between 1981 and 2011, from which the electoral effects of corruption allegations and corruption scandals are analyzed. Information about the extent to which corruption allegations and scandals have occurred is gathered from election reports in several political science journals, and the electoral effects are measured in terms of the electoral performances—the difference in the share of votes between two elections—of all parties in government, as well as the main incumbent party, and the extent to which the governments survive the election. The control variables are GDP growth and unemployment rate the year preceding the election, the effective number of parliamentary and electoral parties, and the level of corruption. The results show that both corruption allegation and corruption scandals are significantly correlated with governmental performances on a bivariate basis; however, not with governmental change. When controlling for other factors, only corruption allegation has an independent effect on government performances. The study thus concludes—in line with previous research—that voters actually punish corrupt politicians, but to a quite limited extent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The only exception is Switzerland, where the so-called magic formula prescribes that the government will be made up by the four main parties, and which in effect precludes governmental turnover. I have also omitted the first free elections in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland, as there were by definition no democratically elected governments to hold accountable in those elections. In contrast, the first free elections in Bulgaria, Croatia, Malta, Romania, Serbia and Slovenia are included, since the preceding elections are considered sufficiently free and competitive. Moreover, both the Czech and Slovak Republics’ first elections are compared to the results in the last Czechoslovak election in 1992. Finally, the 2006 Ukrainian election is excluded as the government for most of the preceding election period was formed under the previous presidential system.

Countries scoring between 8 and 10 are coded as low for corruption, countries scoring between 5 and 7.9 as medium corrupt and countries scoring below 5 as highly corrupt. The first CPI was published in 1995, which means that the figures for the first 15 years are estimated on the basis of the last 15 years. As corruption is considered to be a sticky phenomenon, which changes quite modestly during a short term period, this strategy should not distort the facts in this respect.

A country is considered democratic when it is rated as Free by Freedom House (www.freedomhouse.org) [12]. Years missing indicate that the countries were already considered Free from the starting point of the period under study, i.e. in 1981.

The first democratic elections in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland are omitted since there was no democratic government to hold accountable in those elections.

The first election in the Czech Republic is compared to the last Czechoslovak election in 1992.

In 2002, Yugoslavia was still in existence. It consisted of two federal subjects, Serbia and Montenegro. Between 2003 and 2005, the federation had loosened and the country was called Serbia and Montenegro. In 2006, Montenegro became independent and was rated Free in 2008.

Slovakia was rated Partly free in 1996 and 1997 and Free again in 1998, when the elections were held. Slovakia has been rated as Free since then. The first election in Slovakia is compared to the last Czechoslovak election in 1992.

The 2006 election is omitted since the government for most of the preceding election period was appointed under the previous presidential system.

References

Anduiza, E., Gallego, A., & Munoz, J. (2013). Turning a blind eye. Experimental evidence of partisan bias in attitudes toward corruption. Comparative Political Studies. doi:10.1177/0010414013489081. 0010414013489081.

Bågenholm, A. (2013). The electoral fate and policy impact of ‘anti-corruption parties’ in Central and Eastern Europe. Human Affairs, 23, 174–195.

Barberá, P. et al. (2012). The electoral consequences of political scandals in Spain. Paper presented at the XXII World Congress of Political Science, July 2012.

Chang, E. C. C., Golden, M. A., & Hill, S. J. (2010). Legislative malfeasance and political accountability. World Politics, 62, 2.

Della Porta, D., & Mény, Y. (1997). Democracy and corruption in Europe. London: Pinter.

Dimock, M. A., & Jacobson, G. C. (1995). Checks and choices: the house bank scandal’s impact on voters in 1992. Journal of Politics, 57, 4.

Eggers, A., & Fisher, A. C. (2011). Electoral accountability and the UK parliamentary expenses scandal: Did Voters Punish Corrupt MPs? Working Paper. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1931868

Electoral Studies, volumes 2–32

EPERN Election Briefing. http://www.sussex.ac.uk/sei/research/europeanpartieselectionsreferendumsnetwork/epernelectionbriefings.

Esaiasson, P., & Kumlin, S. (2012). Scandal fatigue? Scandal elections and satisfaction with democracy in Western Europe 1977–2007. British Journal of Political Research, 42, 263–282.

European Journal of Political Research, volumes 22–51.

Freedom House. www.freedomhouse.org.

Heidenheimer, A. J., & Johnston, M. (Eds.). (2009). Political corruption. Concepts and contexts (3rd ed.). New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Heywood, P. (1997). Political corruption: problems and perspectives. Political Studies, 45(3), 417–435.

Huberts, L. (1995). Western Europe and the public corruption. Experts views on attention, extent and strategies. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 3, 2.

Inter-Parliamentary Union. http://www.ipu.org/parline-e/parlinesearch.asp.

Jiménez, F., & Caínzos, M. (2006). How far and why do corruption scandals cost votes? In J. Garrand & J. L. Newell (Eds.), Scandals in the past and contemporary politics. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Klasnja, M. et al. (2012). Pocketbook vs. Sociotropic Corruption Voting. Paper presented at the QoG lunch seminar in Gothenburg May 11, 2012.

Kunicová, J., & Rose-Ackerman, S. (2005). Electoral rules and constitutional structures as constraints on corruption. British Journal of Political Science, 35, 573–606.

Lederman, D., Loayza, N., & Soares, R. R. (2005). Accountability and corruption. Political institutions matter. Economics and Politics, 17(1), 1–35.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., & Stegmaier, M. (2000). Economic determinats of electoral outcomes. Annual Review of Political Science, 3, 183–219.

Manzetti, L., & Wilson, C. (2007). Why do corrupt governments maintain public support? Comparative Political Studies, 40, 949–970.

Müller-Rommel, F., et al. (2004). Party government in Central Eastern European democracies: a data collection (1990–2003). European Journal of Political Research, 43, 869–893.

Peters, J. G., & Welch, S. (1980). The effects of charges of corruption on voting behavior in congressional elections. American Political Science Review, 74, 3.

Reed, S. A. (1999). Punishing corruption: The response of the Japanese electorate to scandals. In O. Feldman (Ed.), Political psychology in Japan: Behind the nails which sometimes stick out (and Get Hammered Down). Commack: Nova Science.

Special Eurobarometer. (2009). 324 attitudes of Europeans towards corruption. http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_325_en.pdf.

Special Eurobarometer. (2012). 374 corruption. http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_374_en.pdf.

Transparency International. www.tranparency.org.

Welch, S., & Hibbing, J. R. (1997). The effects of charges of corruption on voting behavior in congressional elections, 1982–1990. Journal of Politics, 59, 1.

West European Politics, volumes 4–36.

Woldendorp, J., et al. (1998). Party government in 20 democracies: an update (1990–1995). European Journal of Political Research, 33, 125–164.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Country | DemocraticFootnote 4 | No. of electionsFootnote 5 |

Austria | 9 (1983–2008) | |

Belgium | 9 (1981–2010) | |

Bulgaria | 1991 | 6 (1991–2009) |

Croatia | 2000 | 4 (2000–2011) |

Czech RepublicFootnote 6 | 1990 | 5 (1996–2010) |

Denmark | 11 (1981–2011) | |

Estonia | 1991 | 5 (1995–2011) |

Finland | 8 (1983–2011) | |

France | 7 (1981–2007) | |

Germany | 8 (1983–2009) | |

Greece | 11 (1981–2009) | |

Hungary | 1990 | 5 (1994–2010) |

Iceland | 8 (1983–2009) | |

Ireland | 10 (1981–2011) | |

Italy | 8 (1983–2010) | |

Latvia | 1991 | 6 (1995–2011) |

Lithuania | 1991 | 4 (1996–2008) |

Luxemburg | 6 (1984–2009) | |

Malta | 1987 | 6 (1987–2008) |

Montenegro | 2008 | 1 (2009) |

Netherlands | 10 (1981–2010) | |

Norway | 8 (1981–2009) | |

Poland | 1990 | 7 (1993–2011) |

Portugal | 10 (1983–2011) | |

Romania | 1996 | 4 (1996–2008) |

SerbiaFootnote 7 | 2002 | 3 (2003–2008) |

SlovakiaFootnote 8 | 1993 | 5 (1994–2010) |

Slovenia | 1991 | 6 (1992–2011) |

Spain | 9 (1982–2011) | |

Sweden | 9 (1982–2010) | |

UkraineFootnote 9 | 2005 | 1 (2007) |

United Kingdom | 7 (1983–2010) | |

Total | 215 | |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bågenholm, A. Throwing the rascals out? The electoral effects of corruption allegations and corruption scandals in Europe 1981–2011. Crime Law Soc Change 60, 595–609 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-013-9482-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-013-9482-6