Abstract

Welfare is often administered locally, but financed through grants from the central government. This raises the question how the central government can prevent local governments from spending more than necessary. We analyze block grants used in The Netherlands, which depend on exogenous spending need determinants and are estimated from previous period welfare spending. We show that, although these grants give rise to perverse incentives by reducing the marginal costs of welfare spending, they are likely to be more efficient than a matching grant, and more equitable than a fixed block grant.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Thus, we ignore technical inefficiency. Many municipalities contract out programs to help welfare recipients find work to private firms which operate in more than one municipality. Therefore, this assumption does not seem to be unduly unrealistic there.

This is essentially the same as the trade-off between incentives and rent extraction, see Laffont and Martimort (2002, Chapter 2).

Equalization has been advocated on the grounds that it improves locational efficiency (Buchanan 1950, 1952; Buchanan and Goetz 1972; Boadway and Flatters 1982); on equity grounds (Le Grand 1975; Bramley 1990); as an insurance against regional shocks (Bucovetsky 1998; Von Hagen 2006) and in order to improve transparency and thereby facilitate the local decision making process (Allers 2012). For a review of the arguments for equalization, see Boadway (2006).

Every municipality receives a block grant (“participatiebudget”) earmarked for helping unemployed persons find work, for integrating immigrants and for educating adults with insufficient schooling. Unlike the grant aimed at financing local welfare benefits, this grant cannot be used for other purposes. Therefore, we assume it does not enter the local government’s utility function, and we ignore this grant in the following sections. Faber and Koning (2012) provide a detailed analysis of this grant and how it influences the behavior of municipalities.

People losing their job normally are entitled to unemployment benefits for a period which depends on their employment history. After this period, they may apply for a (usually lower) welfare benefit if they have insufficient means to support themselves and their families.

In Toolsema and Allers (2012, Appendix B) we extend the model to include these limits.

We describe the Dutch system as it existed in 2013.

In practice, the grant formula is left unchanged in some years.

It is common to use effort as a strategic variable in this type of models. In our setting, inefficiency can be reinterpreted as being negatively related to effort, and the model could be reinterpreted in terms of effort. We focus the discussion on the variable inefficiency rather than effort because inefficiency is the key variable of interest here, and this makes the results easier to interpret.

The assumption of a maximum inefficiency level does not qualitatively affect the results. It merely avoids the possibility of extreme inefficiency which does not seem to make sense in practice.

In this paper, ‘welfare expenditures’ refers to welfare benefit payments only; they do not include administrative costs.

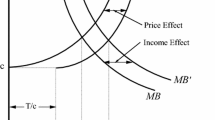

In Fig. 1 we have drawn \(\gamma -\delta B_{t+1}^{\prime }(Z_t)\) as a decreasing function of \(Z_{t}\), but it could alternatively be increasing (or even nonmonotonic) depending on the sign of \(B_{t+1}^{{\prime }{\prime }}(Z_t)\).

Recall that, apart from size differences, differences in the exogenous variables X cause inefficiency levels to differ across local governments (via the administrative cost function \(C\)).

In Toolsema and Allers (2012) we extend the model to include possible loss aversion. The municipality’s objective function may put a greater weight on a deficit than on a surplus.

Some studies of expenditure needs try to control for differences in efficiency by including efficiency-related variables in the regression, e.g., the local tax price or political variables (Duncombe and Yinger 1997; Bradbury and Zhao 2009). Perhaps such variables can be successfully applied to reduce the omitted variable problem to some extent, but it seems highly unlikely that it can be eliminated this way.

We ignore the fact that predicted expenses may not sum to exactly the same amount as actual expenses. Including this would imply scaling, i.e. multiplying each element of the vector \(B_{t+1}\) by the same number, which is determined exogenous of the model.

We assume that the regression model includes the correct set of exogenous variables \(X_{j},\,j=1,\ldots ,n\).

Note that this bias equals \(\gamma \) times the slope from regressing \(Z_{t}\) on \(X\).

In 2001–2003. Until 2001, \(\alpha = 0.10\). Results are given in Table 2.

Calculated as 1/408, where 408 is the number of municipalities.

The grant of medium sized municipalities is determined partly by their share in the previous period, and partly by regression results. The importance of both components depends on the number of inhabitants: with increasing size, regression results increase in importance.

In 2013. Calculated as \(n\), the number of exogenous spending need determinants (14), divided by \(m\), the number of large and medium sized municipalities (216).

Note that as it takes time for data to become available and for regression analyses to be carried out, the time lag in the Netherlands is usually bigger than 1 year (2–3 years). As a result, we are actually assuming here that \(\delta ^{2}\) or \(\delta ^{3}\) is 0.95, which is rather on the safe side.

As a rule of thumb in regression analysis, values exceeding two or three times the average value of \(h_{ii}\) (here: 0.13 or 0.19) are considered influential outliers that merit close inspection, and, possibly, exclusion from the analysis (e.g., Hoaglin and Welsch 1978).

Allers et al. (2013) analyze the way financial incentives influence local government behavior in practice, and describe the theories based on behavioral economics that are relevant in this context.

References

Akai, N., & Sato, M. (2008). Too big or too small? A synthetic view of the commitment problem of interregional transfers. Journal of Urban Economics, 64, 551–559.

Allers, M. A. (2012). Yardstick competition, fiscal disparities, and equalization. Economics Letters, 117, 4–6.

Allers, M. A., Edzes, A., Engelen, M., Geertsema, J. B., de Visser, S., & Wolf, E. (2013). De doorwerking van de financiële prikkel van de WWB binnen gemeenten. Groningen: COELO.

Baicker, K. (2005). Extensive or intensive generosity? The price and income effects of federal grants. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 87, 371–384.

Bird, R. M., & Smart, M. (2002). Intergovernmental fiscal transfers: International lessons for developing countries. World Development, 30, 899–912.

Blank, R. M. (2002). Evaluating welfare reform in the United States. Journal of Economic Literature, 40, 1105–1166.

Boadway, R. (2006). Intergovernmental redistributive transfers: Efficiency and equity. In E. Ahmad & G. Brosio (Eds.), Handbook of fiscal federalism. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Boadway, R., & Flatters, F. (1982). Efficiency and equalization payments in a federal system of government: A synthesis and extension of resent results. Canadian Journal of Economics, 15, 614–633.

Bradbury, K., & Zhao, B. (2009). Measuring non-school fiscal disparities among municipalities. National Tax Journal, LXII, 25–56.

Bramley, G. (1990). Equalization grants and local expenditure needs. The price of equality. Aldershot: Avebury.

Breuillé, M.-L., & Gary-Bobo, R. J. (2007). Sharing budgetary austerity under free mobility and asymmetric information: An optimal regulation approach to fiscal federalism. Journal of Public Economics, 91, 1177–1196.

Breuillé, M.-L., Madiès, T., & Taugourdeau, E. (2010). Gross versus net equalization scheme in a federation with decentralized leadership. Journal of Urban Economics, 68, 205–214.

Buchanan, J. M. (1950). Federalism and fiscal equity. The American Economic Review, 40, 583–599.

Buchanan, J. M. (1952). Federal grants and resource allocation. The Journal of Political Economy, 60, 208–217.

Buchanan, J., & Goetz, C. (1972). Efficiency limits of fiscal mobility: An assessment of the Tiebout model. Journal of Public Economics, 1, 25–43.

Bucovetsky, S. (1998). Federalism, equalization and risk aversion. Journal of Public Economics, 67, 301–328.

Chernick, H. (1998). Fiscal effects of block grants for the needy: An interpretation of the evidence. International Tax and Public Finance, 5, 205–233.

Cornes, R. C., & Silva, E. C. D. (2002). Local public goods, interregional transfers and private information. European Economic Review, 46, 329–356.

Dahlberg, M., & Edmark, K. (2008). Is there a “race-to-the-bottom” in the setting of welfare benefit levels? Evidence from a policy intervention. Journal of Public Economics, 92, 1193–1209.

Duncan, A., & Smith, P. (1996). Modelling local government budgetary choices under expenditure limitation. Fiscal Studies, 16, 95–110.

Duncombe, W., & Yinger, J. (1997). Why is it so hard to help central city schools? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 16, 85–113.

Faber, R. P., & Koning, P. W. C. (2012). Why not fully spend a conditional block grant? CPB Discussion paper 213. The Hague, The Netherlands: CPB.

Gilbert, G., & Rocaboy, Y. (1996). Local public spending in France: The case of welfare programmes at the département level. In G. Pola, G. France, & R. Levaggi (Eds.), Developments in local government finance. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Goodspeed, T. J. (2002). Bailouts in a federation. International Tax and Public Finance, 9, 409–421.

Hayek, F. A. (1945). The use of knowledge in society. American Economic Review, 35, 519–530.

Hoaglin, D. C., & Welsch, E. E. (1978). The hat matrix in regression and ANOVA. The American Statistician, 32, 17–22.

Huber, B., & Runkel, M. (2006). Optimal design of intergovernmental grants under asymmetric information. International Tax and Public Finance, 13, 25–41.

Kok, L., Groot, I., & Güler, D. (2007). Kwantitatief effect WWB. Amsterdam: SEO.

Köthenbürger, M. (2004). Tax competition in a fiscal union with decentralized leadership. Journal of Urban Economics, 55, 498–513.

Ladd, H. F. (1994). Measuring disparities in the fiscal condition of local governments. In J. E. Anderson (Ed.), Fiscal equalization for state and local government finance (pp. 21–54). Westport: Greenwood.

Laffont, J.-J., & Martimort, D. (2002). The theory of incentives: The principal-agent model. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Le Grand, J. (1975). Fiscal equity and central government grants to local authorities. The Economic Journal, 85, 531–547.

Oates, W. E. (1972). Fiscal federalism. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Oates, W. E. (1999). An essay on fiscal federalism. Journal of Economic Literature, 37, 1120–1149.

Raff, H., & Wilson, J. D. (1997). Income redistribution with well-informed local governments. International Tax and Public Finance, 4, 407–427.

Ribar, D. C., & Wilhelm, M. O. (1999). The demand for welfare generosity. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 81, 96–108.

Toolsema, L. A., & Allers, M. A. (2012). Welfare financing: Grant allocation and efficiency. SOM Research Report120004-EEF, University of Groningen.

Van Es, F., & Van Vuuren, D. J. (2010). Minder uitkeringen door decentralisering bijstand. Economisch Statistische Berichten, 95, 4589.

Von Hagen, J. (2006). Achieving economic stabilization by sharing risk within countries. In R. Boadway & A. Shah (Eds.), Intergovernmental fiscal transfers. Principles and practice. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Wildasin, D. (1986). Urban public finance. New York: Harwood.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wouter Vermeulen, Stephen Ferris, participants of the 2011 annual meeting of the Public Choice Society (San Antonio, Texas) and of ASSET 2010 (Alicante), seminar participants at the University of Groningen, and two anonymous referees for useful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Toolsema, L.A., Allers, M.A. Welfare Financing: Grant Allocation and Efficiency. De Economist 162, 147–166 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-014-9228-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-014-9228-6