Abstract

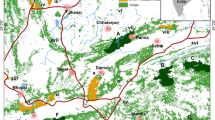

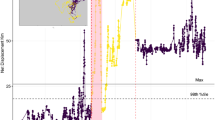

In view of the extensive information available on wolf ecology and habitat suitability, and on the fragmentation of wolf populations by motorways and similar infrastructures, a key factor in their conservation, the aim of the present study was to model the directional connectivity of wolf populations in the region of Galicia in northwest Spain, and to quantify anthropogenic effects on wolf dispersal patterns. To this end, we map the probability of wolf movement by means of known relationships between wolf movement and anthropogenic, vegetation and topographic factors. The relative importance of each factor was quantified by sensitivity analyses. Three types of cost surface were constructed: (a) isotropic surfaces, (b) anisotropic cost surfaces taking into account terrain slope effects in the movement, and (c) surfaces obtained by combining the isotropic and anisotropic surfaces. The results obtained by approaches (a) and (c) indicate that one of the region’s motorways (the AP-9) probably acts as a significant barrier to wolf movement, possibly isolating two subpopulations, while the remaining motorways probably do not have major effects on dispersal. Estimation of lowest-cost routes for wolf displacement allowed identification of areas critical for connectivity, in which it would be of interest to perform detailed studies with more precise input data on motorway course and the location of drainage channels and underpasses, etc. (these being the factors identified by sensitivity analysis to be those with the most marked effects on the cost surfaces). The visualization of connectivity enabled by this approach will allow wolf management and conservation efforts to be focused on critical areas: such efforts might include measures aimed to encourage wolf dispersal through areas in which conflict with human activity is minimized, thus contributing positively to the management of a socially conflictive species. Finally, evaluation of the different cost surfaces suggests that it would be of interest to introduce two modifications to the anisotropic algorithm, to allow the user to weigh the importance of the different input factors, and to allow the inclusion of more than one anisotropic factor in the model.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Adriaensen, F., Chardon, J. P., De Blust, G., Swinnen, E., Villalba, S., Gulinck, H., et al. (2003). The application of “least-cost” modeling as a functional landscape model. Landscape and Urban Planning, 64, 233–247.

Ballard, W. B., Whitman, J. S., & Gardner, C. L. (1987). Ecology of an exploited wolf population in South-Central Alaska. Wildlife Monographs, 98, 1–54.

Barja, I., de Miguel, J., & Bárcena, F. (2003). Señales olfativas y marcaje territorial del lobo ibérico. Quercus, 210, 14–18.

Barrientos, L. M. (2000). Pasado, presente y futuro del lobo en Castilla y León. Quercus, 176, 18–24.

Bárcena, F. (1976). Censo de camadas de lobos en la mitad norte de la provincia de Lugo (año 1975) y algunos datos sobre la población de los mismos. Boletín de la Estación Central de Ecología, 5, 45–54.

Bélisle, M., & Clair, C. C. S. (2001). Cumulative effects of barriers on the movements of forest birds. Conservation Ecology, 5, 9. Available at: http://www.consecol.org/vol5/iss2/art9.

Berg, W. E., & Kuehn, D. W. (1982). Ecology of wolves in North-Central Minnesota. In F. H. Harrington & P. C. Paquet (Eds.), Wolves of the word. Perspectives of behavior, ecology and conservation (pp. 4–11). Park Ridge, NJ: Noyes Publications.

Blanco, J. C. (1993). Efecto barrera: el principio del fin de nuestros mamíferos. Quercus, 83, 23–24.

Blanco, J. C. (1996). La distribución del lobo en España estudios aplicados para paliar el efecto de las autovías. Informe final. Available at: http://194.224.130.163/conserv_nat/acciones/esp_amenazadas/html/vertebrados/Mamiferos/autolobo/indice.htm.

Blanco, J. C. (1997). El lobo en España: apuntes sobre la dinámica de poblaciones. In B. Palacios & L. Llaneza (Eds.), Primer seminario sobre el lobo en los Picos de Europa (pp. 13–27). Asturias: SECEM-Grupo Lobo.

Blanco, J. C. (2001). El hábitat del lobo (Canis lupus): La importancia de los aspectos ecológicos y socioeconómicos. In J. Camprodon, & E. Plana (Eds.), Conservación de la biodiversidad y gestión forestal. Su aplicación a la fauna vertebrada (pp. 415–432). Barcelona: Ed. Universitat de Barcelona.

Blanco, J. C. (2005). Lobo-Canis lupus. In L. M. Carrascal & A. Salvador (Eds.), Enciclopedia virtual de los Vertebrados Españoles. (Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Madrid. Available at http://www.vertebradosibericos.org/).

Blanco, J. C., & Cortés, Y. (1999). Estudios aplicados para paliar el efecto de las autovías en las poblaciones del lobo en España. Madrid: Dirección General de Conservación de la Naturaleza, Ministerio de Medio Ambiente.

Blanco, J. C., & Cortés, Y. (2001). Impact of barriers on a wolf (Canis lupus) population in an agricultural environment in Spain. P. Int. Conf. Ecol. Transport., 517, Keystone, CO, September 24–28, 2001. Raleigh, NC: Center for Transportation and the Environment, North Carolina State University.

Blanco, J. C., & Cortés, Y. (2002). Ecología, censos, percepción y evolución del lobo en España: análisis de un conflicto. Sociedad Española para la Conservación y Estudio de los Mamíferos (SECEM). Málaga: Departamento de Biología Animal. Universidad de Málaga.

Blanco, J. C., & González, J. L. (Eds.) (1992). El libro rojo de los vertebrados de España. Madrid: ICONA, Colección Técnica.

Blanco, J. C., Cuesta, L., & Reig, S. (Eds.) (1990a). El Lobo (Canis lupus) en España: Situación, problemática y apuntes sobre su ecología. Madrid: ICONA.

Blanco, J. C., Cuesta, L., & Reig, S. (1990b). El lobo en España: una visión global. In J. C. Blanco, L. Cuesta, & S. Reig (Eds.), El lobo (Canis lupus) en España. Situación, problemática y apuntes sobre su ecología (pp. 69–94). Madrid: ICONA, Colección Técnica.

Blanco, J. C., Sáenz de Buruaga, M., & Llaneza, L. (2002). Canis lupus Linnaeus, 1758. In L. J. Palomo & J. Gisbert (Eds.), Atlas de los mamíferos terrestres de España (pp. 234–237). Madrid: Dirección General de Conservación de la Naturaleza–SECEM–SECEMU.

Boitani, L. (1982). Wolf management in intensively used areas of Italy. In F. H. Harrington & P. C. Paquet (Eds.), Wolves of the word. Perspectives of behavior, ecology and conservation. Park Ridge, NJ: Noyes Publications.

Boitani, L. (2000). Action plan for the conservation of the wolves (Canis lupus) in Europe. Nature and environment. 118 Council of Europe Publishing.

Callaghan, C., Paquet, P., Wierzchowski, J. (1999). Highway effects on gray wolves within the Golden Canyon, British Columbia. P. Int. Conf. Wildlife Ecol. Transport., September 13–16, Missoula.

Carroll, C., Paquet, P. C., & Noss, R. F. (1999). Modelling carnivore habitat in the rocky mountain region: A literature review and suggested strategy. WWF Canada, Toronto, Ontario, Available at http://www.wwf.ca/NewsAndFacts/Supplemental/literaturereview.pdf.

Carroll, C., Phillips, M. K., Schumaker, N. H., & Smith, D. W. (2003). Impacts of landscape change on wolf restoration success: Planning a reintroduction program based on static and dynamic spatial models. Conservation Biology, 17, 536–548.

Carver, S. J. (1991). Integrating multi-criteria evaluation with geographical information systems. International Journal of Geographical Information Science, 5, 321–339.

Casterline, M., Fegraus, E., Fujioka, E., Hagan, L., Mangiardi, C., Riley, M., et al. (2003). Wildlife corridor design and implementation in Southern Ventura County, California. Bren School of Environmental Science and Management, University of California, Santa Barbara, Available at http://www.bren.ucsb.edu/research/2003Group_Projects/links/Final/links_brief.pdf.

Cayuela, L. (2004). Habitat evaluation for the Iberian wolf Canis lupus in Picos de Europa National Park, Spain. Applied Geography, 24, 199–215.

Ciucci, P., Masi, M., & Boitani, L. (2003). Winter habitat and travel route selection by wolves in the northern Apennines, Italy. Ecography, 26, 223–235.

Conroy, M. J., Cohen, Y., James, F. C., Matsinos, Y. G., & Maurer, B. A. (1995). Parameter-estimation, reliability, and model improvement for spatially explicit models of animal populations. Ecological Applications, 5, 17–19.

Crecente, R., Álvarez, C., & Fra, U. (2002). Economic, social and environmental impact of land consolidation in Galicia. Land Use Policy, 19, 135–147.

Crosetto, M., & Tarantola, S. (2001). Uncertainty and sensitivity analysis: Tools for GIS-based model implementation. International Journal Geographical Information Science, 15, 415–437.

Crosetto, M., Tarantola, S., & Saltelli, A. (2000). Sensitivity and uncertainty analysis in spatial modelling based on GIS. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 81, 71–79.

Cuesta, L., Bárcena, F., Palacios, F., & Reig, S. (1991). The trophic ecology of the Iberian wolf (Canis lupus signatus Cabrera, 1907). A new analysis of stomach's data. Mammalia, 55(2), 239–254.

Cukier, R. I., Fortuin, C. M., Shuler, K. E., Petschek, A. G., & Schaibly, J. H. (1973). Study of the sensitivity of coupled reaction systems to uncertainties in rate coefficients. I. Theory. Journal of Chemical Physics, 59, 3873–3878.

Eastman, J. R. (1989). Pushbroom algorithms for calculating distances in raster grids. Anderson, E., Autocarto 9: Proceedings of the Ninth International Symposium on Computer Assisted Cartography, 288–297, Baltimore, MD.

Eastman, J. R. (2003). Idrisi Kilimanjaro. Guide to GIS and image processing. Worcester, MA: Clark University.

Eastman, J. R., Jin, W., Kyem, P. A. K., & Toledano, J. (1995). Raster procedures for multi-criteria/multi-objective decisions. Photogrammetric Engineering and Remote Sensing, 61, 539–547.

Genovesi, P. (2002). Piano d’azione nazionale per la conservazione del lupo (Canis lupus). Quaderni di conservazione della natura, Ministero dell’Ambiente – Instituto Nazionale per la Fauna Sevatica, Modena, Italy.

Glenz, C., Massolo, A., Kuonen, D., & Schlaepfer, R. (2001). A wolf habitat suitability prediction study in Valais (Switzerland). Landscape and Urban Planning, 55, 55–65.

Grande del Brío, R. (1984). El lobo ibérico. Biología y mitología. Madrid: Hermann Blume.

Guitián, J., De Castro, A., Bas, S., & Sánchez, J. L. (1979). Nota sobre la dieta del lobo (Canis lupus L.) en Galicia. Trabajos Compostelanos de Biología, 8, 95–104.

Gustafson, E. J., & Gardner, R. H. (1996). The effect of landscape heterogeneity on the probability of patch colonization. Ecology, 77, 94–107.

Harrison, D. J., & Chapin, T. G. (1998). Extent and connectivity of habitat for wolves in eastern North America. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 26, 767–775.

Henshaw, R. E. (1982). Can the wolf be returned to New York? In F. H. Harrington & P. C. Paquet (Eds.), Wolves of the word. Perspectives of behavior, ecology and conservation (pp. 395–422). Park Ridge, NJ: Noyes Publications.

IGE (2004). Padrón municipal de habitantes e nomenclator. Santiago de Compostela, Spain: Instituto Galego de Estadística.

INE (1993). Nomenclator de las Ciudades, Villas, Lugares, Aldeas y demás Entidades de Población con especificación de sus núcleos. Madrid, Spain: Instituto Nacional de Estadística.

IUCN (1996). Red list of threatened animals. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

Jedrzejewski, W., Niedzialkowska, M., Nowak, S., & Jedrzejewska, B. (2004). Habitat variables associated with wolf (Canis lupus) distribution and abundance in northern Poland. Diversity and Distributions, 10, 225–233.

Lusseau, D. (2004). The energetic cost of path sinuosity related to road density in the wolf community of Jasper National Park. Ecologia y Sociedad, 9, r1. Available at http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol9/iss2/resp1/.

Martínez Cortizas, A., & Pérez Alberti, A. (Eds.) (1990). Atlas climático de Galicia. Centro de Información e Tecnoloxía Ambiental, Consellería de Medio Ambiente, Xunta de Galicia, Santiago de Compostela, Spain.

Massolo, A., & Meriggi, A. (1998). Factors affecting habitat occupancy by wolves in northern Apennines (northern Italy): A model of habitat suitability. Ecography, 21, 97–107.

Mata, C., Hervás, I., Herranz, J., Suárez, F., & Malo, J. E. (2003). Effectiveness of wildlife crossing structures and adapted culverts in a highway in Northwest Spain. Int. Conf. Ecol. Transport, 265–276, Center for Transportation and the Environment, North Carolina State University. Raleigh, NC.

Mech, L. D. (1970). The wolf. The ecology and behavior of an endangered species. Minneapolis, MN: Univ. of Minnesota Press.

Mech, L. D. (1987). Age, season, distance, direction, and social aspects of wolf dispersal from a Minnesota pack. In B. D. Chepko-Sade & Z. T. Halpin (Eds.), Mammalian dispersal patterns: the effects of social structure on population genetics (pp. 55–74). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Ministerio de Medio Ambiente (1998). III Mapa Forestal de España. Madrid, Spain: Dirección General de Conservación de la Naturaleza.

Mladenoff, D. J., & Sickley, T. A. (1998). Assessing potential gray wolf restoration in the northeastern United States: A spatial prediction of favorable habitat and potential population levels. Journal of Wildlife Management, 62, 1–10.

Mladenoff, D. J., Sickley, T. A., Haight, R. G., & Wydeven, A. P. (1995). A regional landscape analysis and prediction of favorable gray wolf habitat in the Northern Great Lakes Region. Conservation Biology, 9, 279–294.

MMA (1999). Conclusiones. Seminario internacional sobre conservación y gestión del lobo en España. Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Spain, 8–10 de junio de 1999.

Muñoz, J., Felicísimo, Á. M., Cabezas, F., Burgaz, A. R., & Martínez, I. (2004). Wind as a long-distance dispersal vehicle in the Southern Hemisphere. Science, 304, 1144–1147.

Official Journal of the European Communities (1992). Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. http://europa.eu.int/eur-lex/en/consleg/pdf/1992/en_1992L0043_do_001.pdf [Accessed, 02-9-2006].

Olden, J. D., Monroe, J. B., Poff, N. L., & Schooley, R. L. (2004). Context-dependent perceptual ranges and their relevance to animal movements in landscapes. Journal of Animal Ecology, 73, 1190–1194.

Palomo, L. J., & J. Gisbert (Eds.) (2002). Atlas de los mamíferos terrestres de España. Madrid, Spain: Dirección General de Conservación de la Naturaleza–SECEM–SECEMU.

Pueyo Echevarría, J., García López, M. J., & Larraz Duerto, C. (2002). Integración de un modelo digital del terreno en un S.I.G. para el estudio de la dispersión y disminución del ruido generado por transportes. XIV Congreso Internacional de Ingeniería Gráfica. Universidad de Cantabria, Santander, Spain, 5, 6 y 7 de Junio, Available at http://departamentos.unican.es/digteg/ingegraf/cd/ponencias/168.pdf.

Purves, H., & Doering, C. (1999). Wolves and People: Assessing cumulative impacts of human disturbance on wolves in Jasper National Park. PESRI Int. Users Conf., Redlands, CA: Environmental Science Research Institute. Available at http://gis.esri.com/library/userconf/proc99/proceed/papers/pap317/p317.htm.

Quinby, P., Trombulak, S., Lee, S. T., Lane, J., Henry, M., Long, M. R., et al. (1999). Opportunities for wildlife habitat connectivity between Algonquin Park, Ontario and the Adirondack Park, New York. The Greater Laurentian Wildlands Project, Burlington, Vermont. Available at http://www.ancientforest.org/a2a.html.

Rivas-Martínez, S. (1987). Memoria del mapa de series de vegetación de España. Madrid: Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentacón, ICONA, Serie Técnica.

Saaty, T. L. (1977). A scaling method for priorities in hierarchical structures. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 15, 234–281.

Saltelli, A., & Sobol’, I. M. (1995). About the use of rank transformation in sensitivity analysis of model output. Reliability Engineering & Systems Safety, 50, 225–239.

Saltelli, A., Tarantola, S., Campolongo, F., & Ratto, M. (2004). Sensitivity analysis in practice. A guide to assessing scientific models. Ispra (VA), Italy: Wiley, European Commission Joint Research Centre.

Saltelli, A., Tarantola, S., & Chan, K. (1999). A quantitative model-independent method for global sensitivity analysis of model output. Technometrics, 41, 39–56.

Schooley, R. L., & Wiens, J. A. (2003). Finding habitat patches and directional connectivity. Oikos, 102, 559–570.

Singleton, P. H., Gaines, W. L., & Lehmkuhl, J. F. (2002). Landscape permeability for large carnivores in Washington: A geographic information system weighted-distance and least corridor assessment. United States Department of Agriculture. Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station. Paper 549. Portland.

Talegón, J. (2004). La conservación del lobo en la provincia de Zamora. Quercus, 222, 21–27.

Taylor, P. D., Fahrig, L., Henein, K., & Merriam, G. (1993). Connectivity is a vital element of landscape structure. Oikos, 68, 571–573.

Vilá, C., Urios, V., & Castroviejo, J. (1990). Ecología del lobo en La Cabrera (León) y la Carballeda (Zamora). In J. C. Blanco, L. Cuesta, & S. Reig (Eds.), El lobo (Canis lupus) en España. Situación, problemática y apuntes sobre su ecología (pp. 95–108). Madrid: ICONA, Colección Técnica.

Voogd, H. (1983). Multicriteria evaluation for urban and regional planning. Page Bros, London.

Weaver, J. L., Paquet, P. C., & Ruggiero, L. F. (1996). Resilience and conservation of large carnivores in the Rocky Mountains. Conservation Biology, 10, 964–976.

Whittington, J., Clair, C. C. S., & Mercer, G. (2004). Path tortuosity and the permeability of roads and trails to wolf movement. Ecologia y Sociedad, 9(1): 4. Available at http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol9/iss1/art4.

Wiens, J. A. (2002). Riverine landscapes: taking landscape ecology into the water. Freshwater Biology, 47, 501–515.

Acknowledgments

The research presented in this paper was supported by a Grant from the section of the Spanish government “Secretaria de Estado de Educación y Universidades” (MECD-Ref.-2003-0215) and by a Grant for Research Projects from the Galician government “Xunta de Galicia” (PGIDT02RAG29103PR).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rodríguez-Freire, M., Crecente-Maseda, R. Directional Connectivity of Wolf (Canis lupus) Populations in Northwest Spain and Anthropogenic Effects on Dispersal Patterns. Environ Model Assess 13, 35–51 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10666-006-9078-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10666-006-9078-y