Abstract

We extend the study of procedural fairness in three new directions. Firstly, we focus on lotteries determining the initial roles in a two-person game. One of the roles carries a potential advantage over the other. All the experimental literature has thus far focused on lotteries determining the final payoffs of a game. Secondly, we modify procedural fairness in a dynamic—i.e. over several repetitions of a game—as well as in a static—i.e. within a single game-sense. Thirdly, we analyse whether assigning individuals a minimal chance of achieving an advantaged position is enough to make them willing to accept substantially more inequality. We find that procedural fairness matters under all of these accounts. Individuals clearly respond to the degree of fairness in assigning initial roles, appraise contexts that are dynamically fair more positively than contexts that are not, and are generally more willing to accept unequal outcomes when they are granted a minimal opportunity to acquire the advantaged position. Unexpectedly, granting full equality of opportunity does not lead to the highest efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

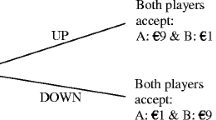

Note that we use the term ‘role’ to indicate whether a participant is a proposer or a receiver in the UG played in the last phase of the Stage Game (see Fig. 1). We use the term ‘position’ to refer to whether a player is Player 1 (favoured) or Player 2 (unfavoured) in the lottery assigning UG roles—that is, \({\mathcal{L}}_{2}\) in Fig. 1.

In their meta-analysis, Oosterbeek et al. (2004) report that the weighted average acceptance rate from 66 UG studies is 84.25 %, whereas average demands equal 59.5 % of the pie in 75 UG experiments.

The probability of acceptance was significantly higher for students attending Economics degrees (\(P=0.009)\), women (\(P=0.029)\), and students with UK citizenship (\(P=0.033)\). Note that including these variables comes at the cost of a considerable loss of observations due to missing variables.

In our experiments, the average expected payoffs for receivers in the last five rounds—seemingly an appropriate measure for “equilibrium” payoffs—are the highest (\(\pounds 3.16\)) in 0 %_FPC, which is arguably the most unfair procedure in our experiments. The only unbiased procedure in our experiments, i.e. the baseline 50 % condition, only yields \(\pounds 2.47\) to receivers and comes fifth in the ranking of expected receivers’ payoffs across treatments. In our case “equilibrium” expected payoff differences are thus an inaccurate proxy for procedural fairness.

References

Alesina, A., & La Ferrara, E. (2005). Preferences for redistribution in the land of opportunities. Journal of Public Economics, 89(5–6), 897–931.

Anand, P. (2001). Procedural fairness in economic and social choice: Evidence from a survey of voters. Journal of Economic Psychology, 22(2), 247–270.

Andreozzi, L., Ploner, M., & Soraperra, I. (2013). Justice among strangers. On altruism, inequality aversion and fairness. Working paper No. 1304, CEEL, Trento University.

Armantier, O. (2006). Do wealth differences affect fairness considerations? International Economic Review, 47(2), 391–429.

Becker, A., & Miller, L. (2009). Promoting justice by treating people unequally: An experimental study. Experimental Economics, 12(4), 437–449.

Bewley, T. (1999). Why wages don’t fall during a recession. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Benabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2006). Belief in the just world and redistributive politics. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(2), 699–746.

Binmore, K., Morgan, P., Shaked, A., & Sutton, J. (1991). Do people exploit their bargaining power? An experimental study. Games and Economic Behavior, 3, 295–322.

Bolton, G. E., Brandts, J., & Ockenfels, A. (2005). Fair procedures: Evidence from games involving lotteries. Economic Journal, 115(506), 1054–1076.

Bolton, G., & Ockenfels, A. (2000). A theory of equity, reciprocity and competition. American Economic Review, 90, 166–193.

Buchan, N., Croson, R., & Johnson, E. (2004). When do fair beliefs influence bargaining behavior? Experimental bargaining in Japan and the United States. Journal of Consumer Research, 31, 181–190.

Burrows, P., & Loomes, G. (1994). The impact of fairness on bargaining. Empirical Economics, 19(2), 201–221.

Cappelen, A. W., Konow, J., Sorensen, E. O., & Tungodden, B. (2013). Just luck: An experimental study of risk-taking and fairness. American Economic Review, 103(4), 1398–1413.

Cappelen, A., Drange, A., Sørensen, E., & Tungodden, B. (2007). The pluralism of fairness ideals: An experimental approach. American Economic Review, 97(3), 818–827.

Charness, G., & Rabin, M. (2002). Understanding social preferences with simple tests. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117, 817–869.

Corneo, G., & Gruner, H. M. (2002). Individual preferences for political redistribution. Journal of Public Economics, 83, 83–107.

Diamond, P. (1967). Cardinal welfare, individualistic ethics, and interpersonal comparison of utility: A comment. Journal of Political Economy, 75(5), 765–766.

Elster, J. (1989). Solomonic judgements: Studies in the limitation of rationality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Erkal, N., Gangadharan, L., & Nikiforakis, N. (2010). Relative earnings and giving in a real-effort experiment. American Economic Review, 101(7), 3330–3348.

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition and cooperation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114, 817–868.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 102, 171–178.

Fong, C. (2001). Social preferences, self-interest, and the demand for redistribution. Journal of Public Economics, 82(2), 225–246.

Frey, B., & Stutzer, A. (2005). Beyond outcomes, measuring procedural utility. Oxford Economic Papers, 57, 90–111.

Gill, D., Prowse, V., Vlassopoulos, M. (2012). Cheating in the workplace: An experimental study of the impact of bonuses and productivity. Available at SSRN 2109698.

Guth, W., & Tietz, R. (1986). Auctioning ulitmatum bargaining positions—How to act rational if decisions are unacceptable? In R. W. Scholz (Ed.), Current issues in West German decision research (pp. 173–185). Frankfurt: Verlag Peter Lang.

Hammond, P. (1988). Consequentialist foundations for expected utility. Theory and Decision, 25(1), 25–78.

Handgraaf, M., Van Dijk, E., Vermunt, R., Wilke, H., & De Dreu, C. (2008). Less power or powerless? Egocentric empathy gaps and the irony of having little versus no power in social decision making. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(5), 1136–1149.

Hargreaves-Heap, S., & Varoufakis, Y. (2002). Some experimental evidence on the evolution of discrimination, co-operation and perceptions of fairness. Economic Journal, 112, 679–703.

Hoffman, E., & Spitzer, M. L. (1985). Entitlements, rights and fairness: An experimental examination of subjects’ concepts of distributive justice. Journal of Legal Studies, 14, 259–297.

Hoffman, E., McCabe, K., Shachat, K., & Smith, V. (1994). Preferences, property rights, and anonymity in bargaining games. Games and Economic Behavior, 7(3), 346–380.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–292.

Karni, E., Salmon, T., & Sopher, B. (2008). Individual sense of fairness: An experimental study. Experimental Economics, 11(2), 174–189.

Karni, E., & Safra, Z. (2002). Individual sense of justice: A utility representation. Econometrica, 70, 263–284.

Keren, G., & Teigen, K. (2010). Decisions by coin toss: Inappropriate but fair. Judgement and Decision Making, 5(2), 83–101.

Konow, J. (2003). Which is the fairest one of all? A positive analysis of justice theories. Journal of Economic Literature, 41(4), 1188–1239.

Krawczyk, M. (2011). A model of procedural and distributive fairness. Theory and Decision, 70(1), 111–128.

Krawczyk, M. (2010). A glimpse through the veil of ignorance: Equality of opportunity and support for redistribution. Journal of Public Economics, 94, 131–141.

Krawczyk, M., & Le Lec, F. (2010). Give me a chance! An experiment in social decision under risk. Journal of Experimental Economics, 13, 500–511.

Leventhal, G. S. (1980). What should be done with equity theory?. Detroit: Springer.

Machina, M. (1989). Dynamic consistency and non-expected utility models of choice under uncertainty. Journal of Economic Literature, 27(4), 1622–1668.

Nozick, R. (1994). The nature of rationality. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Oosterbeek, H., Sloof, R., & van de Kuilen, G. (2004). Cultural differences in ultimatum game experiments: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Experimental Economics, 7(2), 171–188.

Rawls, J. (1999). A theory of justice (rev ed.). Cambridge, MA: Belknap.

Schmitt, P. M. (2004). On perceptions of fairness: The role of valuations, outside options, and information in ultimatum bargaining games. Experimental Economics, 7(1), 49–73.

Schurter, K., & Wilson, B. J. (2009). Justice and fairness in the dictator game. Southern Economic Journal, 76(1), 130–145.

Suleiman, R. (1996). Expectations and fairness in a modified UG. Journal of Economic Psychology, 17, 531–554.

Thibaut, J. W., & Walker, L. (1975). Procedural justice: A psychological analysis. Hillsdale: L. Erlbaum Associates.

Trautmann, S., & van de Kuilen, G. (2014). Process fairness, outcome fairness, and dynamic consistency: Experimental evidence, mimeo.

Trautmann, S., & Wakker, P. (2010). Process fairness and dynamic consistency. Economics Letters, 109(3), 187–189.

Trautmann, S. T. (2009). A tractable model of process fairness under risk. Journal of Economic Psychology, 30(5), 803–813.

Tyler, T. R. (2006). Why people obey the law. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Woolridge, J. M. (2002). Introductory econometrics: A modern approach. Cincinnati, OH: South-Western College Publishing.

Acknowledgments

We thank Iwan Barankay, Dirk Engelmann, Enrique Fatás, Peter Hammond, Andrew Oswald, Elke Renner, Blanca Rodriguez, Tim Salmon, Stefan Traub for useful discussion, as well as participants in the Workshop on ‘Procedural fairness—theory and evidence’, Max Planck Institute for Economics (Jena), the 2008 IMEBE conference, the 2008 European ESA conference, the 2010 Seminar on ‘Reason and Fairness’, Granada, and seminar participants at Nottingham, Royal Holloway, Trento, Warwick. We also appreciate the careful reading of the paper and the insightful suggestions by two anonymous referees and the journal editors. We especially thank Malena Digiuni for excellent research assistance, Stefan Trautmann for fruitful discussion, and Steven Bosworth for his comments on a previous version of the paper. Any errors are our sole responsibility. This project was financed by the University of Warwick RDF grant RD0616. Gianluca Grimalda acknowledges financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (grant ECO 2011-23634), Bancaixa (P1. 1A2010-17), Junta de Andalucía (P07-SEJ-03155), and Generalitat Valenciana (grant GV/2012/045).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grimalda, G., Kar, A. & Proto, E. Procedural fairness in lotteries assigning initial roles in a dynamic setting. Exp Econ 19, 819–841 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-015-9469-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-015-9469-5