Abstract

This paper assesses the implementation of four selected IWRM principles in four very different river basins in Europe and Asia. The four principles relate to all the different aspects of sustainable development—environmental, social, economic and institutional—as well as the factor that is particularly crucial in many countries of the South: implementation capacity. The paper is based on the work performed in the EC-funded STRIVER project, “Strategy and methodology for improved IWRM—An integrated interdisciplinary assessment in four twinning river basins”. The four basins—Tungabhadra and Sesan (in Asia), and Tagus and Glomma (in Europe) exemplify very different problems and challenges with regard to IWRM: different levels of socio-economic development and very varying problems with regard to water quality and availability. The paper shows that the implementation of IWRM is at a fairly early stage in all the four STRIVER basins; and that successful implementation of water resources is dependent not only on the existence of relevant policies, but also the degree to which laws and policies are in fact implemented.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) has become very popular in recent years, although traces can be found in the literature as early as the 1960s and 1970s (García 2008). Indeed, Biswas (2004), asserts that, it was promulgated internationally by the UN during the 1950s; and it can certainly be traced back to the Mar del Plata conference, 1977. The need to establish a balance between economic growth, social equity, and protection of the environment in water management that inspired the development of IWRM gained added momentum at the International Conference on Water and the Environment in Dublin (ICWE 1992), and the concept, which has characteristics of a systems approach (Petit and Baron 2009), has been embraced as a popular and appealing ideology by international agencies, regional bodies and individual countries seeking to protect environmental resources and alleviate poverty. It may be contrasted with the sectoral approach which has predominated in the past, and to a large extent still prevails in practice. The latter promotes coherence between policy, budgeting and resource allocation within a single sector, such as agriculture; but it has been argued that this leads to fragmented and uncoordinated management (Funke et al. 2007). IWRM seeks to apply a systems approach, whereby the component parts of a system are understood in the context of relationships with each other, and with other systems, rather than in isolation. The concept of integration also includes the involvement of those affected by water resource management decisions; hence participation by stakeholders is also a central element in IWRM.

But the concept has been much debated, and criticized. Opponents argue that it is vague, and difficult to implement effectively (Biswas 2004; Saravanan et al. 2009; Turton et al. 2007). Biswas (2008) doubts whether such varied issues as water, energy and agriculture can in fact be integrated, as the processes available at present for their overall management are very different and the expertise required to manage these resources efficiently is also very different. Proponents of IWRM, on the other hand, argue that the philosophy and principles of IWRM offer the most sustainable solution to the challenge of efficiently and equitably allocating water resources (Beukman 2002; Funke et al. 2007). They claim that rather than imposing a rigid framework, it offers a new way of looking at problems and how to solve them (Zaag 2005). In this paper, we assess the strengths and weaknesses of applying IWRM methodology, and more specifically four selected IWRM principles, on the basis of a comparison between four very different river basins in Europe and Asia. The paper is based on the work performed in the EC-funded STRIVER project, “Strategy and methodology for improved IWRM—An integrated interdisciplinary assessment in four twinning river basins”Footnote 1 (Stålnacke et al. 2009). In addition to representing very different biophysical and socio-economic conditions and challenges, these four river basins also provide a range of different examples of transboundary river management—across national, state or county boundaries.

The IWRM principles chosen for assessment

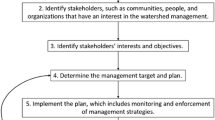

The four IWRM principles we selected for assessment relate to all the different aspects of sustainable development—environmental, social, economic and institutional—as well as the factor that is particularly crucial in many countries of the South: implementation capacity. The first of these, “protection of the catchment and the environment”, relates primarily to the environmental aspect, and requires an adequate understanding of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems in the basin, as well as measurement and monitoring of components and characteristics of the environment affecting surface and groundwater quality and quantity. The emphasis on this principle is vital, since the well-being of humans depends not only on adequate supplies of good quality water, but also on the many forms of life to which water is home. The second principle, “measures to ensure efficient and equitable use of water”, concerns the socio-economic dimension. It relates to the principle that water should be seen as an economic and social good (McNeill 1998). Past failure to recognize the economic value of water has led to wasteful and environmentally damaging uses of the resource. And viewing water as a social good implies ensuring equity in allocation: that all users should have an adequate supply of clean water at an affordable price. Economic instruments are expected to play an important role in providing incentives to consumers to reach the objectives of social equity, ecological sustainability, financial sustainability and economic efficiency (encouraging conservation of water and shifting from low to high value uses). Policy instruments such as measures for reuse, as well as pricing strategies, are assessed in this study. The third principle, “effective governance” relates to the institutional dimension, and includes inter-sectoral integration and coordination: two crucial elements of IWRM. To secure the coordination of water management efforts across water related sectors, and throughout entire water basins, both formal mechanisms and means of co-operation and informal exchange need to be established. Participation of stakeholders is also a part of this integration process, not least in order to raise awareness, among policy-makers and the general public, of the importance of water. Governance in IWRM is thus concerned with integration, coordination, and stakeholder participation—that is access to information and access to decision-making. The fourth topic addressed in this paper is capacity building, which is not only important for effective implementation but also relates to the third principle, since capacity building may also be important to achieve effective public participation. In order for instruments of policy, the legal framework, financing systems and organisational frameworks to function effectively, the different parties involved need to possess not only sufficient information, but also expertise, and incentives. To achieve this, capacity building may be needed at many levels: for water professionals in both public and private water organisations, local and central government, water management organisations and in regulatory organisations, as well as in civil society.

Introduction to the four transboundary river basins

The river basins selected for study—Tungabhadra and Sesan (in Asia), and Tagus and Glomma (in Europe)—exemplify very different problems and challenges with regard to IWRM: different levels of socio-economic development, and very varying problems with regard to water quality and availability.

The Tungabhadra River is a transboundary river shared by the two southern States of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh in India. The upper portion of the Tungabhadra sub-basin is characterized by higher rainfall compared to the middle and lower portion of the basin which is characterized by drought conditions. Here the area is dotted with a large number of decentralised, localised water harvesting systems called tanks. The cropping system in the canal irrigated areas is dominated by multiple crops of rice and to a lesser extent sugar cane, the main water consuming crops. Population density in the sub-basin is quite high (7.2 million people in 71,417 km2) and the population is rapidly growing. There are an increasing number of expanding small towns and industrial areas which contributes to the growing problems of water quality in the basin.

The Se San is a trans-boundary river originating in Vietnam running through North-eastern Cambodia where it joins the Mekong River. There is considerable variability in rainfall during the year. Population density in the area is relatively low, and most of the people living in the riparian areas belong to ethnic minorities involved in small scale subsistence agriculture and fishing. The share of industry in the economy is small and poverty and famine is still part of the realities of life for a substantial number of people. In a desire to modernize, the central authorities are promoting an increased utilization of the water resources, especially with regard to hydropower production, and large scale irrigation. Unfortunately, these projects have created unforeseen negative impacts for the local inhabitants that live according to the traditional modes of water use utilization. From the transboundary point of view, too, there are conflicts related to hydropower development and management of hydropower reservoirs upstream vs. downstream areas.

The Tagus is a transboundary river between Spain and Portugal. The basin is partly characterized by drought conditions as the bulk of the area receives rainfall within the range of 500 to 700 mm per year. There are both irrigated lands (3.5% of total area) and rain fed arable lands (26%). The major water uses are irrigation, hydropower, urban and industrial consumption, water transfer and as coolant in thermal power plants. The main pressures are water abstraction for irrigation, urban supplies and industrial use and water transfers. There are still many problems threatening water quality within the basin, such as deficient water treatment, especially in small towns; over-exploitation, which increases the concentration of pollutants and nutrients; and diffuse pollution sources (MAOT 1999, 2002).

The Glomma river, in Norway, is heavily regulated for hydropower purposes, with 26 reservoirs and diversions and 47 power stations. The population density in the basin is only 29 persons/km2 and the total population living in the catchment is about 675,000—about 15% of Norway’s total population. In total, the agricultural area covers 5.8% of the catchment. A major user of water is electricity production, as 99% of electricity in Norway comes from hydropower. The most important water management issue is the regulation of the water flow regime which impacts on landscape and water ecosystems and causes eutrophication of Mjøsa—Glomma and Norway’s largest lake.

In the next section we summarise the major challenges facing the four river basins, in relation to the four IWRM principles on which we have chosen to focus.

IWRM status; Protection of catchments and the environment

Pressures on the water resources, abstraction of water

The sectors which commonly compete for water in the four river basins in Europe and Asia are hydropower, agriculture, irrigation, and industry. Which of these sectors that is most important depends mainly on climatic factors and on the level of economic development. In water-rich river basins, such as the Glomma and the Sesan, hydropower development occupies a dominant position. The regulation of the natural water flow regime and the construction of dams impact the aquatic ecosystem and the surrounding landscape. Hydropower installations affect downstream ecosystems by changing the water and sediment regime and blocking migratory movements of fish and other aquatic animals. The impacts of hydropower development, however, vary with topography and socio-economic development. Conflicts related to the use of hydropower are much greater in Sesan than in the three other case basins, as many people who live along the Sesan are dependent on the river for their livelihood. The topography around Sesan is such that forests, agricultural areas and villages get submerged by hydropower development. Conflicts related to hydropower development in Glomma mainly concern impacts on recreation opportunities and local identity.

Various measures are put in place to mitigate impacts on the watercourse. An important measure with regard to hydropower development is so-called ‘environmental flow’, that is, rules governing the release of water so as to ensure water levels and flows well suited for the overall river ecology and human water use interests. In Norway, environmental flow/minimum flows must, according to national legislation (Watercourse regulation Act 1917) be assessed for each hydropower development project above 40 GWh/yr. In the Tagus basin, the Albufeira Convention ensures a minimum discharge during dry periods to the Portuguese part of the basin; however there has been no requirement of environmental flow for regulated river stretches in general. In the Sesan basin, in recent years, a minimum water release is required for large hydropower projects, but no assessment of the needed environmental flow is made (Nhung 2005). There are no requirements for minimum water release or environmental flow in Tungabhadra.

In the drier Tagus and Tungabhadra basins, conflicts are related to water availability for the different water use sectors, exacerbated by the impacts of climate change. With increasing urbanization, competing interests between agriculture and urban water supplies are particularly severe. In addition, the existing basin plans in Tagus do not fully account for the effects of climate and land cover changes on water availability. In the Spanish part of the river Tagus, adaptation to the actual situation each year is reactive rather than anticipatory; the water systems therefore do not accommodate drought periods effectively. In Tungabhadra, the main conflicts are due to high demand for water between upstream and downstream farmers. The current cropping pattern in Tungabhadra is not in line with that recommended by government, and more water demanding cash crops are planted (discussions with the Tungabhadra board, Manasi et al. 2008). In neither Tagus nor Tungabhadra do planning documents include a description of the impact of actions, e.g. of changes in river water flow on species or ecosystems or hydrology (Appendix, Table 1). The basin plans in Tagus, however, do provide characteristic of the river basin ecology and of the water resources (Spanish Tagus Basin Hydrologic Plan 2000; Portuguese Tagus River Basin Water Plan 2001). A general description of impacts on species groups is provided in planning documents in Sesan, but not on landscape level or related to hydrology (Appendix, Table 1). In Glomma, description of impacts on species groups, landscape, hydro-morphology, and on the socio-economic conditions is a pre-condition for all projects larger than 1,000 kW (Water resource Act 2000).

Pressure on the water resource, water pollution

Pressure on water quality due to effluents and waste occurs in all the four case basins, but both the pollution level and the level of conflict vary considerably. Water standards and monitoring programs are reported to exist in all the basins, but monitoring is said to be insufficient in most cases (Nesheim et al. 2008). In Tungabhadra and in Sesan (mainly on the Cambodian side), people perceive water quality as poor, and water pollution has resulted in the killing of fish, foul smell, skin disease and stomach ailments. In Tungabhadra, domestic and industrial pollution, combined with deforestation, mining activities, use of pesticides and fertilizers, and over-exploitation of groundwater cause contamination of surface water and groundwater. The water quality as monitored by the Karnataka pollution control board is much below standard, a situation which has been an issue of contestation and protests from civil society (Tungabhadra stakeholder report 2007). In the Sesan River, Cambodian side polluted water is mainly caused by slow running and still waters related to hydropower production (Tiodolf and Stålnacke 2009). In the Sesan (mainly Cambodian side) and Tungabhadra basins poor water quality has a major impact on livelihoods, as untreated water is used for drinking and in agriculture (Barkved et al. 2009). Although the Environment Protection Act and other legal and administrative regulations exist in Tungabhadra to check pollution from industry, monitoring and enforcement is rather weak. In Sesan monitoring of water quality is performed yearly according to specified standards, and reported to the Department of Natural Resources and the Environment; but harm caused to ecosystem and human health in basins (whether by point-source or diffuse pollution) is not monitored.

In the Glomma basin, pollution levels have improved considerably over the last 25 years and wastewater is, with very few exceptions, treated in waste water treatment plants. However, the river continues to be polluted by agriculture, and by many small settlements which do not have efficient effluent treatment systems, creating conflicts with respect to the use of the river as drinking water supply (Eklo et al. 2009, DN Report 2002-1b). In the Spanish part of the Tagus basin, treatment of waste water from small towns and from Madrid is insufficient, causing problems for those crops which depend on water quality. Runoff from agriculture, and leakages from old power stations, is other important sources of pollution in this area (de Almeida et al. 2009). Little is known about the extent of contamination of waste water in the Portuguese part of the Tagus River, but it seems not to be a major problem (MAOT 1999, 2002). Implementation of the Water Framework Directive should ensure proper pollution control and monitoring in both Glomma and Tagus (EC 2000).

IWRM status; Measures for efficient and equitable use of water

Water efficiency and measures for reuse

Initiatives to treat water as an economic good are evident in all the four basins, although differing considerably with regard to approach and strength (Appendix, Table 2). Measures to ensure efficient use of water including water saving and re-use are mainly found in the water scarce basins Tagus and Tungabhadra. Pressure to ensure efficient use of water exists where water shortage is a problem, thus few initiatives have been found in the water rich Glomma and Sesan basins. The Spanish situation seems to be the most developed one, with incentives for the adoption of new water saving technologies and efficient transport, and the production of non water-intensive crops and cultivars. Despite this, in Spain as much as 60% of the water is wasted in agriculture and 35% in urban areas due to high losses in the distribution ditches and pipes (Manasi et al. 2008). Also several studies from Tagus document that current patterns of water use involve excessive waste (MOAT 1999). In Portugal, comparable statistics are not available, but it is likely that the same situation applies. Combined savings in agriculture, industry and domestic water supplies could significantly defer investment in costly new water-resource development and have an enormous impact on the sustainability of future supplies. In the Tungabhadra basin, also, water availability is limited and a combination of overuse and system losses have resulted in low overall efficiencies and extensive land degradation (Reddy 2006).

Price strategy/instrument

Pricing policies exist in all the basins, but these are most fully developed in the Tagus basin where both Spain and Portugal (DL 2008) apply the ‘user-pays’ approach, based on the costs and benefits of provision of water—although the volume consumed is not measured but only estimated (Appendix, Table 2). The level of water charges is very low, and one of the aims of the AGUA programme (actions for the management and use of water) is to relate water prices more closely to actual costs (acquisition and treatment) and economic benefits (A.G.U.A. programme 2004). Farmers and households pay very little for water use, and several studies report over-irrigation in the Tagus basin because of the low price of water (kept low for political reasons, so as to reduce production costs of the farmers) (MAOT 1999). In the Sesan basin, households in urban areas have to pay for fresh water; and farmers pay for irrigation, but the price is low (Nhung et al. 2009). In the Glomma basin, households pay for water and sanitation services, and farmers pay for irrigation water delivered through the municipal supply; fees for water use are low and related mainly to cost recovery in favour of municipalities. In Sesan, Tagus and Tungabhadra, policies give special treatment to irrigation, charges being more or less “political” in order to support the agricultural sector.

Instruments to ensure equitable use

It seems that water is seen as a social as well as an economic good in all the four basins (Appendix, Table 2). Special provisions exist in most basins (though not in Glomma) for favourable treatment for the less rich and developed communities. Poor people do not have to pay for water in Sesan or in Tagus. In Tungabhadra, all irrigation users have to pay some water charges, though these may be very low. Social inequity in relation to water supply is evident mainly in Tungabhadra and Sesan river basins, due to a combination of poor infrastructure and weak governance, while a particular problem exists in the Tungabhadra basin as water rights are tied to land rights, which tends to exacerbate inequalities. Besides this, a rather inefficient practice seems to be applied in the Tungabhadra, where users pay irregularly or on a flat basis, as a consequence of the lack of a metering system (discussions with Urban Local Bodies along the basin, 2009).

IWRM status; Institutional analysis and stakeholder participation

Coordination sectors

In Norway it is the Ministry of Oil and Energy which has overall responsibility for Water Quantity Management, while the Ministry of Environment has overall responsibility for Water Quality Management; but responsibilities have been increasingly decentralized to municipalities which, under the Planning and Building Act, have the main responsibility for land use planning along river plains. Thus, formally, there is an effective split between the legal and institutional arrangements for qualitative and quantitative aspects of water management. The management structure in Glomma has been criticized as being fragmented, both in the horizontal and vertical management dimensions (Østdahl et al. 2002), as there is a multitude of actors with different responsibilities. However, close coordination has been ensured in actual planning, licensing procedures and legislation. The ongoing process of implementing the WFD has resulted in a slight re-organization of the water governance structure—from management units according to administrative borders to borders of the river basin level with one coordination regional administrative unit, the river basin authority.

In the transboundary Tagus basin, the river is managed at the supranational level under the Albufeira Convention under which both countries have obligations with respect to water policy and provision of information, Borges 2007, Correia 1999. This convention has established a rather effective organization, “Conference of the Parties” to coordinate transboundary cooperation. At the national level in Spain, water resources management is controlled by the Water Authority, the Tagus basin authority, which works under the auspices of the Ministry of the Environment and Rural and Maritime Environment. In accordance with the WFD and the A.G.U.A. programme, a new Hydrological plan for the Tagus basin will be developed and prepared in a collaborative and consensual manner. At the national level in Portugal, new regional public authorities have been created in accordance with the WFD. These include, hydrographic region administrations and the restructured national water institute which belongs to the Ministry of Environment, Spatial Planning and Regional Development. The Hydrographic region administrations will promote the basin plan, and the Hydrographic Region management plans.

The Sesan in Vietnam is controlled primarily by the Ministry of Natural Resources and the Environment (MoNRE), with more local control being exercised by the ministry’s local Departments (DoNRE) and relevant provincial Peoples’ Committees. The National Water Resource Strategy calls for ground and surface waters to be managed together; however, the reality falls short of this ambition, and institutional coordination with respect to water management may be regarded as poor. There is a profusion of organizations at different levels, with ill-defined roles and functions. Many of the organizations involved with water resource management at the local or district level are linked to irrigation or hydropower. The power to allocate water resources lies with Peoples’ Committees, but it is not clear how decisions are taken since the criteria are unspecified. Hydropower is the dominant water use; and although in periods of water shortage priority is in principle to be given to water for human consumption, it is not clear how licenses for use in such circumstances can be amended.

Water management in Tungabhadra is performed at the state level, not the basin level. Water abstractions are administered by sectoral departments at the state level, subject to the approval of the state Water Resources Department. The existing allocation system at this level fails to provide for variation to take account of changing climatic or resource availability, especially in the context of droughts, and ignores connections between uses of ground and surface waters. The National Water Policy of 2002 sets out water use priorities as follows: drinking water; irrigation; hydro-power; ecology; agro-industries and non-agricultural industries; and navigation and other uses. It does not, however, set out the criteria to be used by licensing authorities when allocating water use rights.

Access to information and to decision making

In Norway, public participation in planning processes has a long tradition and is regulated by the Planning and Building Act (Appendix, Table 3). In Glomma, plans and project proposals are made available to the public through clearly defined processes including public hearings. Any initiative taken, related to hydropower, construction or road/railway construction, has to be presented by the executing organization to the general public, which can submit objections or propose modifications. All information held by the authorities is, in principle, open for all citizens. All Acts in Norway require that information and analysis prepared by the authorities in planning documents should be available for the public. More specifically administrative agencies shall hold general environmental information relevant to their areas of responsibility and functions, and make this information accessible to the public. In this respect, implementation of the WFD, requiring the full participation of all users in the watershed, will not lead to any major changes.

Spain and Portugal have ratified three UNECE conventions containing provisions for access to information and public participation (Appendix, Table 3). But despite these conventions, and national legislation, stakeholder and public participation in decision-making has been relatively limited. The WFD opens up decision-making to more sub-national levels and diversifies the perspectives offered by various interest groups, beyond traditionally dominant groups such as the sectors of hydropower and agriculture. In Spain, the AGUA (Actions for the Management and Use of Water) Programme and the WFD require the elaboration of a new Hydrological Plan for the Tagus basin. The preparation of the new plan involves greater participation by the regions and also more public participation (Correia 2005; Brito 2008). All proposed new water utilizations will now require appropriate permission/concession licenses. In Portugal the preparation of the Tagus River basin Plan involved the main actors and stakeholders, and legislation provides for public participation. It should be noted, however, that public sessions related to the plan were mainly attended by participants from sectors such as agriculture and industry with a strong interest in the outcome of any decisions; the general public is not usually aware of the importance of involvement in questions related to water use and conservation.

The Law on Environmental Protection in Vietnam provides for public consultation and mandatory environmental impact studies (Appendix, Table 3). The national hydropower exploitation plan involves relocation of people whose land will be submerged by the dams and reservoirs, and stakeholder workshops have been held for each hydropower project. The implementation of the EIA process in relation to hydropower development has not always been optimal. Critics argue that the process is inherently flawed since the EIA comes very late in the project planning process and is a static, one-off exercise. The level and effectiveness of public involvement during EIA has also come under serious criticism in several cases (Ojendal et al. 2002). Also, the flow of information from the centre to local authorities, and to the local communities affected in Cambodia and Vietnam, is irregular and not always effective.

Water policy documents and legislation in India contain clauses to promote stakeholder participation, e.g. the Participatory Irrigation Management Act and the National Water Policy, 2002, and the Karnataka State Water Policy, 2002 (Appendix, Table 3). However, often people do not get access to information, and the availability of data in an understandable form has been limited. The only area where involvement of the stakeholders is sought is in the area of irrigation water management or drinking water, as part of the sectoral reforms. There is no consultation amongst the different stakeholders on the question of inter-sectoral water allocation; this is done at the level of the government departments. Decision-making is dominated by public officials, in particular engineers; and multi-stakeholder fora are not in place, although through water user associations, Water Development Committees and self help groups there are some opportunities for civil society participation. These, however, play a very limited role, as the officers influenced by the politicians of the respective departments take most of the decisions. It is claimed that the public hearings are often manipulated to suit the interests of the proponents of the project, and the hearings often have no significant effect on the final outcome.

IWRM status; Capacity building

Capacity building is included in many water policies and strategies in Sesan, Tungabhadra and Tagus case study basins; however, these official statements are seldom operationalised to any great extent by the authorities. Capacity building initiatives in the basins are mainly run by different types of organizations (NGOs). In Cambodia, most training and capacity building programmes are run by foreign donors, due to financial constraints on domestic authorities. The Department of Fisheries does however, contribute to capacity building through information concerning sustainable fishing techniques and fish farming. In Vietnam, regional and local authorities are active with projects concerned with the resettlement of people, helping local people adjust to their new areas of living. In Tungabhadra, funds are allocated specifically for capacity building but it is mainly only farmers that undergo training programmes. In Tagus, the type of capacity building includes information provided by environmental NGOs and aimed at increasing knowledge of environmental problems. Some information is provided by the Spanish and Portuguese water authorities aiming at decreasing the negative impacts of excessive use of water in agriculture, and teaching young people concepts relating to the water cycle and to water resources conservation. In Glomma, capacity building is seldom mentioned in policy documents or law, but there are strong competence and capacity building initiatives in the Norwegian administration and governance structure, as has been experienced in relation to the implementation of the WFD.

Discussion

Integrated water resource management is about allocating water resources efficiently and equitably among different water uses, taking account of the needs of the ecosystem and control of pollution. Various recommended principles and procedures for successful implementation of IWRM have been developed (GWP toolbox, UN-water 2008), and this paper has been concerned with four of them which are of particular relevance. It is evident that these principles need to be seen in context; in the four STRIVER case basins, the nature and extent of problems of water scarcity and water pollution vary considerably, as does the extent to which they are effectively mitigated. Although a number of agreed standards and monitoring procedures have been established, monitoring programs are in most of the basins insufficient; and wastewater treatment is still a big challenge in Tagus, Sesan and Tungabhadra. Knowledge of the river basin ecosystems and the water resources is a prerequisite for effective management; but, with the exception of the Glomma basin, impacts of actions on the ecological conditions in the basins are in general poorly known. In the Sesan and Tungabhadra basins, policies have been established to conserve the river basin ecology, but these are only to a limited extent implemented. This is particularly serious given the absence of established rules for environmental flow. Others have also experienced that low priority is attached to river basin ecosystems, and argued that IWRM, as implemented in practice, pays little attention to the ecosystem’s role as provider of water resources and other goods and services (Radif 1999; Jewitt 2002; Leendertse et al. 2008)—even though the definition of IWRM (GWP 2000) and the GWP toolbox emphasise ecological sustainability. It appears that the Water Framework Directive (WFD) being implemented in the European Union is more effective in this regard—perhaps because the WFD is a directive, while IWRM is merely a framework of different principles and tools. The WFD requires characterization of alluvial and terrestrial ecological conditions and an action plan to reach the goal of good ecological and chemical status within the specified time frame (2015). Though water quality problems still exist, water pollution has been significantly reduced in most European countries, fostered by growing public awareness and legislation (Dietrich and Funke 2009). Interestingly, it seems that the WFD and other legislation have had less impact on the “efficient use of water”. An appropriate response to emerging water shortages, such as in the Tagus and Tungabhadra basins, would be to increase efficiency and introduce measures for reuse of water; but this is only to a certain degree occurring. Over-irrigated areas in Tagus results in an excess of water consumption and pollution of groundwater (Manasi et al. 2008), and there exist in Tungabhadra few measures to increase water use efficiency (SOPPECOM 2008). There is obviously still a need to improve the efficiency of industrial use through proper pricing and providing credits for reuse and recycling and strict enforcement of effluent quality standards. Studies of other basins (Kansiime 2002, Gumbo and Zaag 2002) have similar findings: revealing relatively little focus on water use efficiency and equity. Gumbo and Zaag (2002) argue that this is due to a coalition between engineers, financiers and politicians; and an unwillingness by politicians to explore options for behavioural change.

Successful protection of water resources is dependent not only on the existence of relevant policies, but also the degree to which laws and policies are in fact implemented. In other words, it is the management and the institutional situation which ultimately determine the outcome. And weak institutions can lead not only to inefficiency, but also inequity, since they may result in the allocation of water being determined largely on the basis of power and influence. This is why transparency in decision making, and public participation, are important. Access to information and participation in decision making are supported by legislation in all the case basins, but there is often a large gap between the participatory principle and its implementation in practice, particularly in social environments characterized by strong hierarchic relationships, as in India and Vietnam. Countries with long standing democracies, such as Norway, Spain and Portugal, tend to be more conductive to IWRM, as civil society in these countries historically have engaged more in decision making, in contrast to developing countries (Petit and Baron 2009). Public participation in the Tagus basin used to be rather limited, despite relevant legislation and procedures, due to the strong representation of sectors such as hydropower and agriculture; but this is changing in line with the requirements of the WFD. Effective participation requires public education and capacity building. These are, regrettably, often absent; but NGOs are becoming important actors in river basin management in the Tagus, Sesan and Tungabhadra basins—raising the question of what may be the consequence of their replacing the role of the state. They are creating space for stakeholders through NGO forums and through NGO participation in projects and networks. Even when not integrated into the policy system, the expertise and materials they offer can be a resource for stakeholders.

Conclusion

The implementation of IWRM plans is at a fairly early stage in all the four STRIVER basins in Europe and Asia. This seems to be the case in most countries (Tapela 2002; Biswas 2008; Turton et al. 2007). Spain, Portugal and Norway are bound by the WFD to set up an administrative system for water management based on hydrological basin boundaries, in contrast to the Sesan and the Tungabhadra basins. But administrative boundaries can be bridged to a large degree by successful coordination and management practices; and some (e.g. Biswas 2008) question whether integrated management is technically and institutionally possible.

This raises the question of what would constitute successful implementation of IWRM. The concept is both demanding and wide ranging, including aspects such as integration of different disciplines and sectors, capacity building, public participation and protection of the water resource. And there is a danger that it may fail to take into account and adapt to local conditions (Petit and Baron 2009). This paper has shown the very varying contexts in which IWRM might be applied—with regard not only to physical but also socio-political conditions, development and management practices and modes of governance and legislation. It is debatable to what extent the procedures and guidelines that have been developed as constituting best practice are well adapted to these varying situations, and necessary in order to reach the overall aim of sustainable development. In this context, we would emphasise that IWRM is a process (GWP 2000), and note that integration should be seen not only as integration between different sectors but also the integration of stakeholders into this process.

Notes

More information on the IWRM assessment can be found in the STRIVER report (2008) which is based on individual basin reports prepared by researchers from the respective river basins.

References

AGUA programme (2004) Programa A.G.U.A, Actuaciones para la Gestion y la Utilizacion del Agua: Intervention for the Management and Utilization of Water

Barkved LJ, Fazi S, Lo Porto A (eds) (2009) Scientific report on pollution source assessment, including source apportionment results, and pollution prevention measures STRIVER Report No. D 7.1, Part 2 http://kvina.niva.no/striver/Disseminationofresults/tabid/70/Default.aspx

Beukman R (2002) Access to water: some for all or all for some? Phys Chem Earth 27:721–722

Biswas KA (2004) From Mar del Plata to Kyoto: an analysis of global water policy dialogue. Glob Environ Change 14:81–88

Biswas KA (2008) Integrated water resources management: is it working? Water Resour Dev 24(1):5–22

Borges O (2007) A Convenção de Albufeira e o novo ciclo de planeamento, El nuevo ciclo de planificación hidrológica en España—La elaboración de los planes hidrológicos, Madrid, Spain

Brito AG (2008) A reforma institucional para a gestão da água em Portugal: as Administrações de Região Hidrográfica—novas ferramentas para uma nova política (The institutional reform for the water management in Portugal: the hydrographic regions administration—new tools for a new policy). ARH-Norte, Administração da Região Hidrográfica do Norte, MAOTDR

Correia FN (1999) O regime de caudais na Convenção Luso-Espanhola (The flow regime in the Luso-Spanish Convention). Workshop on the Water Resources Luso-Spanish Convention, IST, Lisbon, Portugal

Correia FN (2005) “Turning political commitment into action”, Statement of Mr. Franscisco Nunes Correia, Minister of Environment, Spatial Planning and Regional Development at the Thirteenth Session of the Commission on Sustainable Development. United Nations, New York

de Almeida AB, Portela MM, Machado M (2009) A case of transboundary water agreement—the Albufeira Convention, STRIVER Technical Brief No. 9 http://kvina.niva.no/striver/Disseminationofresults/tabid/70/Default.aspx

Dietrich J, Funke M (2009) Integrated catchment modelling within a strategic planning and decision making process: Wera case study. Phys Chem Earth 34:580–588

DL (2008) Decree-Law n.º 97/2008, 11th June, Regime económico financeiro dos recursos hídricos (Water resources economical-financial regime), Portugal

DN report (2002) Norwegian millennium ecosystem assessment -Pilot Study 2002. The Directorate for Nature, Norway

EC (2000) Directive 2000 EU Water Framework Directive, Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and the Council of 23 October 2000 Establishing a framework for community action in the field of water policy

Eklo OM, Bolli R, Kværner J, Sveistrup T, Hofmeister F, Solbakken E, Jarvis N, Stenemo F, Romstad E, Glorvigen B, Guren TA (2009) Tools for environmental planning to reduce risks of leaching and runoff of pesticides to groundwater. 18th World IMACS/MODSIM Congress, Cairns, Australia http://mssanz.org.au/modsim09

Funke N, Oelofse SHH, Hattingh J, Ashton PJ, Turton AR (2007) IWRM in developing countries: lessons from the Mhlatuze catchment in South Africa. Phys Chem Earth 32:15–18

García LE (2008) Integrated water resources management:a “small step for conceptualists, a giant step for practitioners. Water Resour Dev 24(1):23–36

Global Water Partneship (2000) Global water partnership, integrated water resouces management. Global water partnership, Stockhom

Gumbo B, Zaag PV (2002) Water losses and the political constraints to demand management: the case of the City of Mutare, Zimbabwe. Phys Chem Earth 27:805–813

GWP (2000) Global Water Partnership, Toolbox http://www.gwptoolbox.org

ICWE International conference on water and environment (1992) The Dublin statement on water and sustainable development. http://www.un-documents.net/h2o-dub.htm

Jewitt G (2002) Can integrated water resources management sustain the provision of ecosystem goods and services? Phys Chem Earth 27:887–895

Kansiime F (2002) Introduction—Water and development: ensuring equity and efficiency. Phys Chem Earth 27:801–803

Karnataka State Water Policy (2002) Government of Karnataka

Leendertse K, Mitchell S, Harlin J (2008) IWRM and the environment: a view on their interaction and examples where IWRM led to better environmental management in developing countries. http://www.wrc.org.za

Manasi S, Raju KV, Latha N, Sekhar NU, Lana-Renault N, Vicente-Serrano S, Portela M M, Betaâmio de Almeida A, Machado M (2008) Competing water uses—current status and issues in Tungabhadra and Tagus River Basins, STRIVER Task Report No. 9.1 http://kvina.niva.no/striver/Disseminationofresults/tabid/70/Default.aspx

MAOT (1999) Plano de Bacia Hidrográfica do Rio Tejo (Tagus River Basin Plan). Vol. I, II, III and IV, Lisbon, Portugal

MAOT (2002) Plano Nacional da Água (National Water Plan). Vol. I and II, Ministério do Ambiente e do Ordenamento do Território, 2002 Lisbon, Portugal

McNeill D (1998) Water as an economic good. Nat Resour Forum 22(4):253–261

National Water Policy (2002) Ministry of Water Resources, Government of India

Nesheim I, McNeill D, Stålnacke P, Sekhar NU, Grizzetti B, Allen AA, Barton D, Beguería-Portugés S, Berge D, Bouraoui F, Campbell D, Deelstra J, García-Ruiz JM, Gooch GD, Joy K, Lana-Renault N, Lo Porto A, Machado M, Manasi S, Nhung DK, Paranjape S, Portela MM, Rieu-Clarke A, Saravanan VS, Thaulow H, Vicente-Serrano S. (2008) First IWRM assessment report for the four case basins: Glomma, Tagus, Sesan and Tungabhadra. STRIVER Report D5.1. 71p. http://kvina.niva.no/striver/Disseminationofresults/tabid/70/Default.aspx

Nhung DTK (2005) Environmental impact assessment for hydropower projects in Vietnam. Institute of Energy- Ministry of Industry Report, 2005 Hanoi, Vietnam

Nhung DTK, Gooch GD, Rieu-Clarke A, Nesheim I, Berge D (2009) Strategies and recommendations for river basin management in Sesan, STRIVER Report No. D10.4 http://kvina.niva.no/striver/Disseminationofresults/tabid/70/Default.aspx

Ojendal J, Mathur V, Sithirith M (2002) Environmental governance in the Mekong; Hydropower site selection processes in the Se San and Sre Pok Basins. SEI/REPSI report series,4. Stockholm

Østdahl T, Skurdal J, Kaltenborn BP, Sandlund OT (2002) Possibilities and constraints in the management of the Glomma and Lågen river basin in Norway. Arch Hydrobiol 13:471–490

Petit O, Baron C (2009) Integrated water resources management: from general principles to its implementation by the state. The case of Burkina Faso. Nat Resour Forum 33:49–59

Portuguese Tagus River basin Water Plan (2001) Procesl, Gibb, Hidroproject, HP, Plano de Bacia Hidrografica do Rio Tejo, Instituto da Agua

Radif AA (1999) Integrated water resources management (IWRM): an approach to face the challenges of the next century and to avert future crises. Desalination 124:145–153

Reddy KC (2006) Report of the Committee, G.O. WRD 152 vibashi 04 (Part 1) Upper Bhadra Project (Scheme A), Government of Karnataka

Saravanan VS, McDonald GT, Mollinga PP (2009) Critical review of Integrated Water Resources Management: moving beyond polarised discourse. Nat Resour Forum 33:76–86

SOPPECOM (2008) Innovative Technology and Institutional Options in Rainfed and Irrigated Agriculture Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore, IndiaNo. Of Strategy and methodology for improved IWRM Striver Task Report 9.6

Spanish Tagus Basin Hydrologic Plan (2000) Plan Hidrológico de la Cuenca del Tajo, Madrid. Ministerio de Medio Ambiente

Stålnacke P, Nagothu US, Deelstra J, Thaulow H, Barkved L, Berge L, Nesheim I, Gooch GD, Rieu-Clarke A, Nhung DK, Manasi S, Lo Porto A, Grizzetti B, Beguería Portugués SB (2009) Integrated Water Resources Management: STRIVER efforts to assess the current status and future possibilities in four river basins

Tapela BN (2002) The challenge of integration in the implementation of Zimbabwe’s new water policy: case study of the catchment level institutions surrounding the Pungwe-Mutare water supply project. Phys Chem Earth 27:993–1004

Tiodolf AM, Stålnacke P (2009) A limnological study in the Sesan River in Cambodia during the dry season: focus on toxic cyanobacteria and coliform bacteria. STRIVER Technical Brief No. 12 http://kvina.niva.no/striver/Disseminationofresults/tabid/70/Default.aspx

Tungabhadra stakeholder report (2007) http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/Striver.pdf

Turton AR, Hattingh J, Claassen M, Roux DJ, Ashton PJ (2007) Towards a model for ecosystem governance: an integrated resource management example. In: Turton AR, Hattingh J, Maree GA, Roux DJ, Claassen M, Strydom W (eds) Governance as a trialouge—government-society-science in transition. Springer, Berlin, pp 1–25

UN-water (2008) Status report on IWRM and water efficiency plans for CSD 16. |www.unwater.org/downloads/UNW_Status_Report_IWRM.pdf

Water course regulation act (1917) Act No. 17 of 14 December 1917 relating to regulations of watercourses http://www.nve.no/en/About-NVE/Acts-and-regulations/

Water resources act (2000) Act 2000-11-24 nr 82: Lov om vassdrag og grunnvann http://www.regjeringen.no/nb/dok/lover_regler/lover/vannressursloven.html?id=506923

Zaag PV (2005) Integrated water resources management: relevant concept or irrelevant buzzword? A capacity building and research agenda for Southern Africa. Phys Chem Earth 30:867–871

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Nesheim, I., McNeill, D., Joy, K.J. et al. The challenge and status of IWRM in four river basins in Europe and Asia. Irrig Drainage Syst 24, 205–221 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10795-010-9103-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10795-010-9103-9