Abstract

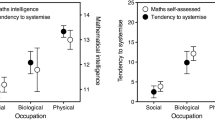

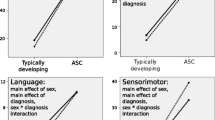

Baron-Cohen’s [(2002) Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 6, 248–255] ‘extreme male brain’ theory of autism is investigated by examining the relationships between theory of mind, central coherence, empathising, systemising and autistic-like symptomatology in typical undergraduates. There were sex differences in the expected directions on all tasks. Differences according to discipline were found only in central coherence. There was no evidence of an association between empathising and systemising. In the second study, performance on the Mechanical Reasoning task was compared with Systemising quotient and the Social Skills Inventory was compared with the Empathising Quotient. Moderate, but not high correlations were found. Findings are broadly consistent with the distinction between empathising and systemising but cast some doubt on the tasks used to measure these abilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Baron-Cohen, S. (2002). The extreme male brain theory of autism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 6, 248–255.

Baron-Cohen, S. (2003). The essential difference: Men, women and the extreme male brain. London: Penguin Books Ltd.

Baron-Cohen, S., Bolton, P., Wheelwright, S., Scahill, V., Short, L., Mead, G., et al. (1998). Does autism occur more often in the families of physicists, engineers, and mathematicians? Autism, 2, 296–301.

Baron-Cohen, S., & Hammer, J. (1997). Is autism an extreme form of the “male brain”? Advances in Infancy Research, 11, 196–217.

Baron-Cohen, S., Leslie, A. M., & Frith, U. (1985). Does the autistic child have a theory of mind? Cognition, 21, 37–46.

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Hill, J., Raste, Y., & Plumb, I. (2001a). The “reading the mind in the eyes” test revised version: A study with normal adults and adults with asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42(2), 241–251.

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Skinner, R., Martin, J. G., & Clubley, E. (2001b). The Autism-Spectrum Quotient: Evidence from Asperger syndrome/high functioning autism, males, females, scientists and mathematicians. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31, 5–17.

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Stott, C., Bolton, P., & Goodyer, I. (1997). Is there a link between engineering and autism? Autism, 1(1), 101–109.

Bennett, G. K., Seashore, H. G., & Wesman, A. G. (1974). Differential Aptitude Tests (5th ed.). New York: Psychological Corporation.

Briskman J., Happe F., & Frith U. (2001). Exploring the cognitive phenotype of autism: Weak “central coherence” in parents and siblings of children with autism II: Real-life skills and preferences. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42(3), 309–316.

Frith, U. (2003). Autism: Explaining the enigma. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Frith, U., & Happe, F. (1994). Autism: “beyond theory of mind”. Cognition, 50, 115–132.

Hoffman, M. L. (1977). Sex differences in empathy and related behaviours. Psychological Bulletin, 84(4), 712–722.

Jarrold, C., Butler, D. W., Cottingham, E. M., & Jimenez, F. (2000). Linking theory of mind and central coherence in autism and in the general population. Developmental Psychology 36(1), 126–138.

Lawson, J., Baron-Cohen, S., & Wheelwright, S. (2004). Empathising and systemising in adults with and without Asperber syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34, 301–310.

Morgan, B., Maybery, M., & Durkin, K. (2003). Weak central coherence, poor joint attention and low verbal ability: Independent deficits in early autism. Developmental Psychology, 39(4), 646–656.

Riggio, R. E. (1989). Social Skills Inventory. USA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Voyer, D., Voyer, S., & Bryden, M. P. (1995). Magnitude of sex differences in spatial abilities: A meta-analysis and consideration of critical variables. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 250–270.

Wechsler, D. (1999). Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. San Antonio, USA: Psychological Corporation.

Witkin, H. A., Oltman, P. K., Raskin, E., & Karp, S. A. (1971). A manual for the embedded figures test. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Maggie Snowling for her helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper, and the students who took part in the research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carroll, J.M., Chiew, K.Y. Sex and Discipline Differences in Empathising, Systemising and Autistic Symptomatology: Evidence from a Student Population. J Autism Dev Disord 36, 949–957 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0127-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0127-9