Abstract

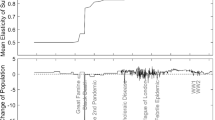

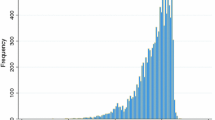

This paper presents a quantitative theory of development that highlights three mechanisms that relate schooling, fertility, and growth. First, we point out that in the early stages of development, fertility and schooling may rise together as the schooling of younger children increases their relative contribution to family income when they turn working age. Second, the model contains a supply-side theory of schooling that generates a rise in schooling independent of technological change. Third, we introduce a direct negative effect of industrialization on fertility that does not operate through human capital and the quantity-quality tradeoff. An initial quantitative assessment of the theoretical mechanisms is conducted by calibrating and applying the model to United States history from 1800 to 2000. We find that the demise in family production is an important factor reducing fertility in the 19th century and schooling of older children is dominant factor reducing fertility in the 20th century. The same model is applied to England from 1740 to 1940, where we offer two complimentary explanations for the rise in fertility from 1740 to 1820. The first is based on the rapid expansion in the cottage industry and the second on the increased relative productivity of children. We also find that the subsequent fall in fertility from 1820 to 1940 cannot be explained without introducing child labor/compulsory schooling laws.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Alvarez F. (1999). Social mobility: The Barro–Becker children meet the Loury–Laitner dynasties. Review of Economic Dynamics 2, 65–103

Armengaud A. (1976). Population in Europe 1700–1914. In: Cipolla C(eds) The industrial revolution. New York, Harper & Row and Barnes & Noble

Atack J., Bateman F., Parker W. (2000a). The farm, the farmer and the market. In: Engerman S., Gallman R(eds) The Cambridge economic history of the United States. Vol. II. ch 6 New York, Cambridge University Press, pp. 245–284

Atack J., Bateman F., Parker W. (2000b). Northern agriculture and the western movement. In: Engerman S., Gallman R.(eds) The Cambridge economic history of the United States Vol.II ch.7. New York, Cambridge University Press, pp. 285–328

Barro R. (1993). Macroeconomics. New York, John Wiley and Sons

Barro R.J., Becker G.S. (1989). Fertility choice in a model of economic growth. Econometrica 57, 481–501

Becker, G.S. (1960). An economic analysis of fertility. In Demographic and economic change in developed countries. New Jersey: Princeton University Press

Becker G.S. (1981). A treatise on the family. Cambridge MA, Harvard University Press

Becker G. S., Barro R.J. (1988). A Reformulation of the economic theory of fertility. Quarterly Journal of Economics 103, 1–25

Becker G.S., Lewis H.G. (1973). On the Interaction between the quantity and quality of children. Journal of Political Economy 81, S279-S288

Benhabib J., Rogerson R., Wright R. (1991). Homework in macroeconomics: Household production and aggregate fluctuations. Journal of Political Economy 99, 1166–1187

Bongaarts J., Watkins S. (1996). Social interactions and contemporary fertility transitions. Population and Development Review 22, 639–682

Caldwell J.C. (1982). Theory of fertility decline. London, Academic Press

Caplow T., Hicks L., Wattenberg B. (2001). The first measured century. Washington DC, The AEI Press

Carter S.B., Ransom R.L., Sutch R. (2003). Family matters: The life-cycle transition and the unparalleled fertility decline in Antebellum America. In: Guinnane T.W., Sundstrom W.A., Whately W.(eds) History matters: Essays on economic growth, technology, and demographic change. Stanford, Stanford University Press

Craig L. (1993). To sow one acre more. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press

Caselli, F., Gennaioli, N. (2005). Dynastic management. Mimeo

Cipolla C. (1969). Literacy and development in the west. Middlesex, Penguin Books

Cipolla C. (1974). The economic history of the world population. Baltimore, Penguin Press

Clark, G. (2005). The conditions of the working-class in England, 1209–2004. University of California-Davis Working Paper #05–39

Clark G. (2005). Human capital, fertility, and the industrial revolution. University of California—Davis, Mimeo

Crafts N. (1995). Exogenous of endogenous growth? The industrial revolution reconsidered. Journal of Economic History 55, 745–772

Crafts N. (1997). The human development index and changes in standards of living: Some historical comparisons. European Review of Economic History 1, 299–322

Cunningham H. (1990). The employment and unemployment of children in England c. 1680–1851. Past and Present 126, 115–150

de la Croix D., Doepke M. (2003). Inequality and growth: Why fertility matters. American Economic Review 93(4): 1091–1113

Doepke M. (2004). Accounting for fertility decline during the transition to growth. Journal of Economic Growth 9, 347–383

Doepke M. (2005). Child mortality and fertility decline: Does the Barro-Becker model fit the facts?. Journal of Population Economics 18: 337–366

Ferguson R., Wascher W. (2004). Lessons from past productivity booms. Journal of Economic Perspectives 18(2): 3–28

Galor O. (2005). From stagnation to growth: Unified growth theory. In: Aghion P., Durlauf S., (eds) Handbook of economic growth. Amsterdam, North Holland

Galor O., Moav O. (2002). Natural selection and the origins of economic growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics 117, 1133–1192

Galor, O., & Moav O. (2006). Das Human-Kapital: A theory of the demise of the class structure Review of Economic Studies, 73, 85-117.

Galor O., Weil D.N. (1996). The gender gap, fertility, and growth. American Economic Review 86, 374–387

Galor O., Weil D.N. (2000). Population, technology, and growth: From Malthusian stagnation to the demographic transition and beyond. American Economic Review 90(4): 806–828

Goldin, C. (1999). A brief history of education in the United States. NBER Historical Paper #119

Goldin, C. Katz, L. (2003). The “virtues” of the past: Education in the first hundred Years of the new republic. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 9958. Cambridge, MA.

Goldin C., Sokoloff K. (1984). The relative productivity hypothesis of industrialization: The American case, 1820 to 1850. Quarterly Journal of Economics 99, 461–490

Gollin D., Parente S., Rogerson R. (2000). Farm work, home work, and international productivity differences. University of Illinois, Mimeo

Gordon R.J. (1999). U.S. economic growth since 1870: One big Wave?. American Economic Review (Papers and Proceedings) 89(2): 123–128

Greenwood J. Yorukoglu M. (1997, 1974). Carnegie-Rochester conference series In public policies. Amsterdam, North Holland

Greenwood J., Seshadri A. (2002). The U.S. demographic transition. American Economic Review (Papers and Preceedings) 92(3): 153–159

Greenwood, J., Seshadri, A. (2003). Technological progress and economic transformation forthcoming in the P. Aghion, S. Durlaff (Eds.), Handbook of economic growth. Amsterdam: North Holland.

Guinnane T., Sundstrom W.A., Whately W. (eds) History matters: essays on economic growth, technology, and demographic change. Stanford, Stanford University Press

Haines M. (2000). The population of the United States, 1790–1920. In: Engerman S.,Gallman R.(eds) The Cambridge economic history of the United States. New York, Cambridge University Press

Hansen G., Prescott E. (2002). Malthus to Solow. American Economic Review 92, 1205–1217

Harley K. (1998). Cotton textile prices and the industrial revolution. Economic History Review 51, 49–83

Hazan M., Berdugo B. (2002). Child labour, fertility, and economic growth. Economic Journal 112, 810–828

Hill G., Johnston G., Campbell S., Birdsell J. (1987). The medical and demographic importance of wet-nursing. Canadian Bulletin of Medical History 4, 183–192

Horrell S., Humphries J. (1995). The exploitation of little children: child labor and the family economy in the industrial revolution. Explorations in Economic History 32, 485–516

Hudson, P. (2004). Industrial organization and structure. In Floud, R., Johnson, P. (Eds.), The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Britain, 1, 28–56.

Hudson P. King S.A. (2000). Two textile townships, c. 1660–1820: A comparative demographic analysis. Economic history review 53, 706–741

Johnson P. (1998). A history of the American people. New York, Harper Collins

Jones C. (2001). Was an industrial revolution inevitable? Economic growth over the very long run. Advances in Macroeconomics 1, 1–43

Kalemli-Ozcan S. (2002). Does mortality decline promote economic growth?. Journal of Economic Growth 7, 411–439

Kalemli-Ozcan S. (2003). A stochastic model of mortality, fertility, and human capital investment. Journal of Development Economics 62, 103–118

Kaestle C., Vinovskis M. (1980). Education and social change in nineteenth-century Massachusetts. CambridgeL, Cambridge University Press

Knodel J., Van de Walle E. (1986). Lessons from the Past: Policy implications of historical fertility studies. In: Coale A., Cotts Watkins S., (eds) The decline of fertility in europe. Princeton, Princeton University Press

Lagerloff N. (2006). The Galor-Weil model revisited: A quantitative exercise. Review of Economic Dynamics 9, 116–142

Lamoreaux N. (2003). Rethinking the transition to capitalism in the early American northeast. Journal of American History 90(2): 437–461

Lebergott S. (1964). Manpower in economic growth: The American record since 1800. New York, McGraw-Hill

Levine D. (1987). Reproducing families: The political economy of English population history. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press

Lindert P. (1980). Child costs and economic development. In: Easterlin R.(ed) Population and economic change in developing countries. Chicago, University of Chicago Press

Lindert P. (2004). Growing public. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press

Margo R. (2000). The labor force in nineteenth century. In: Engerman S., Gallman R.(eds) The Cambridge economic history of the United States. New York, Cambridge University Press

Mitch D. (1992). The rise of popular literacy in Victorian England. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press

Moav O. (2005). Cheap children and the persistence of poverty. Economic Journal 115, 88–110

Parente S.L., Rogerson R., Wright R. (2000). Homework in development economics: Household production and the wealth of nations. Journal of Political Economy 108, 680–687

Randall, S. S. (1871). History of the common school system of the State of New York. New York: Ivison, Blakeman, Taylor and Co.

Rangazas P. (2002). The quantity and quality of schooling and U.S. labor productivity growth (1870–2000). Review of Economic Dynamics 5, 932–964

Restuccia D. (2004). Barriers to capital accumulation and aggregate total factor productivity. International Economic Review 45, 225–238

Ruggles S. (2001). Living arrangements and the well-being of older persons in the past. Population Bulletin of the United Nations 42/43: 111–161

Ruggles, S. (2005). Intergenerational coresidence and economic opportunity of the younger generation in the United States, 1850–2000. Minnesota Population Center Working Paper.

Schofield R. (1985). English marriage patterns revisited. Journal of Family History 10, 2–20

Schofield R. (2000). Short-run and secular demographic responses to fluctuations in living standards in England, 1540–1834. In: Bengtsson T., Saito O. (eds) Population and the Economy. New York, Oxford University Press

Sharlin A. (1986). Urban-rural differences in fertility in Europe during the demographic transition. In: Coale A., Cotts Watkins S.(eds) The decline of fertility in Europe. Princeton, Princeton University Press

Soares R. (2005). Mortality reductions, educational attainment, and fertility choice. American Economic Review 95(2): 580–601

Sokoloff K., Dollar D. (1997). Agricultural seasonality and the organization of manufacturing in early industrial economics: The contrast between England and the United States. Journal of Economic History 57, 288–321

Soltow L., Stevens E. (1981). The rise of literacy and the common school in the United States: A socioeconomic analysis to 1870. Chicago, University of Chicago Press

Tamura R. (2002). Human capital and the switch from agriculture to industry. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 27, 207–242

Tamura R. (2006). Human capital and economic development. Journal of Development Economics 79, 26–72

Tan, J. P., Haines, M. (1984). Schooling and demand for children. Historical persepctives. World Bank Staff Working Papers #697.

Wallis J. (2000). American government finance in the long Run: 1790–1990. Journal of Economic Perspectives 14, 61–82

Walton G., Rockoff H. (2002). History of the American Economy (9th ed.). Australia, South-Western

Woods R. (2000). The demography of Victorian England and Wales. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press

Wrigley E.A. (2004). British population during the long eighteenth century. In: Floud R., Johnson P.(eds) The Cambridge economic history of modern britain 1, 57–95

Young A. (1992). A tale of two cities: Factor accumulation and technical change in Hong Kong and Singapore. In: Blanchard O., Fisher S(eds) NBER Macroeconomics annual. Cambridge, Massachuetts: MIT Press

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lord, W., Rangazas, P. Fertility and development: the roles of schooling and family production. J Econ Growth 11, 229–261 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-006-9005-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-006-9005-8