Abstract

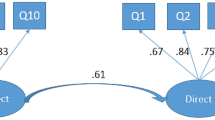

Introduction An employer offer of temporary job modification is a key strategy for facilitating return-to-work for musculoskeletal conditions, but there are no validated scales to assess the level of support for temporary job modifications across a range of job types and organizations. Objective To pilot test a new 21-item self-report measure [the Job Accommodation Scale (JAS)] to assess its applicability, internal consistency, factor structure, and relation to physical job demands. Methods Supervisors (N = 804, 72.8 % male, mean age = 46) were recruited from 19 employment settings in the USA and Canada and completed a 30-min online survey regarding job modification practices. As part of the survey, supervisors nominated and described a job position they supervised and completed the JAS for a hypothetical worker (in that position) with an episode of low back pain. Job characteristics were derived from the occupational informational network job classification database. Results The full response range (1–4) was utilized on all 21 items, with no ceiling or floor effects. Avoiding awkward postures was the most feasible accommodation and moving the employee to a different site or location was the least feasible. An exploratory factor analysis suggested five underlying factors (Modify physical workload; Modify work environment; Modify work schedule; Find alternate work; and Arrange for assistance), and there was an acceptable goodness-of-fit for the five parceled sub-factor scores as a single latent construct in a measurement model (structural equation model). Job accommodations were less feasible for more physical jobs and for heavier industries. Conclusions The pilot administration of the JAS with respect to a hypothetical worker with low back pain showed initial support for its applicability, reliability, and validity when administered to supervisors. Future studies should assess its validity for use in actual disability cases, for a range of health conditions, and to assess different stakeholder opinions about the feasibility of job accommodation strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Turner JA, Franklin G, Fulton-Kehoe D, Sheppard L, Stover B, Wu R, et al. ISSLS prize winner: early predictors of chronic work disability: a prospective, population-based study of workers with back injuries. Spine. 2008;33:2809–18.

Schartz HA, Hendricks DJ, Blanck P. Workplace accommodations: evidence based outcomes. Work. 2006;27:345–54.

Bouknight RR, Bradley CJ, Luo Z. Correlates of return to work for breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:345–53.

Wang PP, Badley EM, Gignac MA. Perceived need for workplace accommodation and labor-force participation in Canadian adults with activity limitations. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1515–8.

Waters TR, MacDonald LA. Ergonomic job design to accommodate and prevent musculoskeletal disabilities. Assist Technol. 2001;13:88–93.

Carroll C, Rick J, Pilgrim H, Cameron J, Hillage J. Workplace involvement improves return to work rates among employees with back pain on long-term sick leave: a systematic review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32:607–21.

Solovieva TI, Dowler DL, Walls RT. Employer benefits from making accommodations. Disabil Health J. 2011;4:39–45.

Krause N, Dasinger LK, Neuhauser F. Modified work and return to work: a review of the literature. J Occup Rehabil. 1998;8:113–39.

Shaw WS, Pransky G, Patterson W, Winters T. Early disability risk factors for low back pain assessed at outpatient occupational health clinics. Spine. 2005;30:572–80.

Shaw WS, Pransky G, Fitzgerald TE. Early prognosis for low back disability: intervention strategies for health care providers. Disabil Rehabil. 2001;23:815–28.

Weir R, Nielson WR. Interventions for disability management. Clin J Pain. 2001;17(4 Suppl):S128–32.

Franche RL, Cullen K, Clarke J, Irvin E, Sinclair S, Frank J, et al. Workplace-based return-to-work interventions: a systematic review of the quantitative literature. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15:607–31.

Franche RL, Severin CN, Hogg-Johnson S, Lee H, Cote P, Krause N. A multivariate analysis of factors associated with early offer and acceptance of a work accommodation following an occupational musculoskeletal injury. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51:969–83.

Mitchell TL, Kovera MB. The effects of attribution of responsibility and work history on perceptions of reasonable accommodations. Law Hum Behav. 2006;30:733–48.

Guzman J, Yassi A, Cooper JA, Khokhar J. Return to work after occupational injury: family physicians’ perspectives on soft-tissue injuries. Can Family Physician. 2002;48:1912–9.

Schreuer N, Myhill WN, Aratan-Bergman T, Samant D, Blanck P. Workplace accommodations: occupational therapists as mediators in the interactive process. Work. 2009;34:149–60.

Shaw WS, Hong QN, Pransky G, Loisel P. A literature review describing the role of return-to-work coordinators in trial programs and interventions designed to prevent workplace disability. J Occup Rehabil. 2008;18:2–15.

Costa-Black KM, Durand M-J, Imbeau D, Baril R, Loisel P. Interdisciplinary team discussion on work environment issues related to low back disability: a multiple case study. Work. 2007;28:249–65.

Westmoreland MG, Williams RM, Amick BC 3rd, Shannon H, Rasheed F. Disability management practices in Ontario workplaces: employees’ perceptions. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27:825–35.

Nordqvist C, Holmqvist C, Alexanderson K. Views of laypersons on the role employers play to return to work when sick-listed. J Occup Rehabil. 2003;13:11–43.

Van Duijn M, Miedema H, Elders L, Burdorf A. Barriers for early return-to-work of workers with musculoskeletal disorders according to occupational health physicians and human resource managers. J Occup Rehabil. 2004;14:31–41.

Kenny DT. Employers’ perspectives on the provision of suitable duties in occupational rehabilitation. J Occup Rehabil. 1999;9:267–76.

Shaw WS, Feuerstein M. Generating workplace accommodations: lessons learned from the integrated case management study. J Occup Rehabil. 2004;14:207–16.

Mustard CA, Kalcevich C, Steenstra IA, Smith P, Amick B. Disability management outcomes in the Ontario long-term care sector. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20:481–8.

van Duijn M, Lotters F, Burdorf A. Influence of modified work on return to work for employees on sick leave due to musculoskeletal complaints. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37:172–9.

Kosny A, Lifshen M, Pugliese D, Majesky G, Kramer D, Steenstra I, et al. Buddies in bad times? The role of co-workers after a work-related injury. J Occup Rehabil. 2013;23:438–49.

Johansson G, Lundberg O, Lundberg I. Return to work and adjustment latitude among employees on long-term sickness absence. J Occup Rehabil. 2006;16:185–95.

Shaw WS, Feuerstein M, Miller VI, Lincoln AE. Clinical tools to facilitate workplace accommodation after treatment of an upper extremity disorder. Assist Technol. 2001;13:94–105.

Tveito TH, Shaw WS, Huang YH, Nicholas M, Wagner G. Managing pain in the workplace: a focus group of challenges, strategies, and what matters most to workers with low back pain. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32:2035–45.

Huang YH, Pransky GS, Shaw WS, Benjamin KL, Savageau JA. Factors affecting the organizational responses of employers to workers with injuries. Work. 2006;26:75–84.

Shaw WS, Huang YH. Concerns and expectations about returning to work with low back pain: identifying themes from focus groups and semi-structured interviews. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;15:1269–81.

Busse JW, Dolinschi R, Clarke A, Scott L, Hogg-Johnson S, Amick BC 3rd, et al. Attitudes towards disability management: a survey of employees returning to work and their supervisors. Work. 2011;40:143–51.

Aas RW, Ellingsen KL, Linøe P, Möller A. Leadership qualities in the return to work process: a content analysis. J Occup Rehabil. 2008;18:335–46.

Shaw WS, Robertson MM, Pransky G, McLellan RK. Training to optimize the response of supervisors to work injuries–needs assessment, design, and evaluation. AAOHN J. 2006;54:226–35.

Wilkie R, Pransky G. Improving work participation for adults with musculoskeletal conditions. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2012;26:733–42.

Costa Lda C, Koes BW, Pransky G, Borkan J, Maher CG, Smeets RJ. Primary care research priorities in low back pain: an update. Spine. 2013;38:148–56.

Sabata D, Williams MD, Milchus K, Baker PM, Sanford JA. A retrospective analysis of recommendations for workplace accommodations for persons with mobility and sensory limitations. Assist Technol. 2008;20:28–35.

Village J, Backman CL, Lacaille D. Evaluation of selected ergonomic assessment tools for use in providing job accommodation for people with inflammatory arthritis. Work. 2008;31:145–57.

Lincoln AE, Feuerstein M, Shaw WS, Miller VI. Impact of case manager training on worksite accommodations in workers’ compensation claimants with upper extremity disorders. J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44:237–45.

Brooker AS, Cole DC, Hogg-Johnson S, Smith J, Frank JW. Modified work: prevalence and characteristics in a sample of workers with soft-tissue injuries. J Occup Environ Med. 2001;43:276–84.

National Research Council and the Institute of Medicine.: Musculoskeletal disorder and the workplace: low back and upper extremities. 2001 panel on musculoskeletal disorders and the workplace. Commission on behavioral and social sciences and education. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2001.

Peterson N, Mumford M, Borman W, Jeanneret PR, Fleishman EA, Levin KY, et al. Understanding work using the occupational information network (O*NET): implications for practice and research. Pers Psychol. 2001;54:451–92.

Alterman T, Grosch J, Chen X, Chrislip D, Peterson M, Krieg E Jr, et al. Examining associations between job characteristics and health: linking data from the occupational information network (O*NET) to two U.S. national health surveys. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50:1401–13.

DeCoster J.: Overview of factor analysis. Retrieved October 28, 2011 from http://www.stathelp.com/notes.html, 1998.

Kamakura WA, Wedel M. Factor analysis and missing data. J Mark Res. 2000;37:490–8.

van Prooijen J-W, van der Kloot WA. Confirmatory analysis of exploratively obtained factor structures. Educ Psychol Meas. 2001;61:777–92.

Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999;6:1–55.

Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural equation models. Psychol Bull. 1990;107:238–46.

Brown TA. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: The Guilford Press; 2006.

Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Beverly hills, CA: Sage; 1993. p. 136–62.

Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WC. Multivariate data analysis, Upper Saddle River. NJ: Prentice-Hall International; 1998.

Lepine JP, Briley M. The increasing burden of depression. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7(Suppl 1):3–7.

Feuerstein M, Luff GM, Harrington CB, Olsen CH. Pattern of workplace disputes in cancer survivors: a population study of ADA claims. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1:185–92.

Duijts SF, van Egmond MP, Spelten E, van Muijen P, Anema JR, van der Beek AJ.: Physical and psychosocial problems in cancer survivors beyond return to work: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2013; [epub ahead of print].

Wang YC, Kapellusch J, Garg A.: Important factors influencing the return to work after stroke. Work. 2013; [epub ahead of print].

Worcester MU, Elliott PC, Turner A, Pereira JJ, Murphy BM, LeGrande MR et al.: Resumption of work after acute coronary syndrome or coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Heart Lung Circ. 2013; [epub ahead of print].

Hepburn CG, Kelloway EK, Franche RL. Early employer response to workplace injury: what injured workers perceive as fair and why these perceptions matter. J Occup Health Psychol. 2010;15:409–20.

Pransky G, Shaw W, McLellan R. Employer attitudes, training, and return-to-work outcomes: a pilot study. Assist Technol. 2001;13:131–8.

Helmhout PH, Staal JB, Heymans MW, Harts CC, Hendriks EJ, de Bie RA. Prognostic factors for perceived recovery or functional improvement in non-specific low back pain: secondary analyses of three randomized clinical trials. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:650–9.

White M, Wagner S, Schultz IZ, Murray E, Bradley SM, Hsu V, et al. Modifiable workplace risk factors contributing to workplace absence across health conditions: a stakeholder-centered best-evidence synthesis of systematic reviews. Work. 2013;45:475–92.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by CIHR Grant MOP-102571, Supervisors’ perspectives on accommodating back injured workers: a mixed-methods study (PI: V Kristman) and by intramural research funding (Project LMRIS 09-01) of the Liberty Mutual Research Institute for Safety (PI: W Shaw).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: The Standard Case Vignette for Supervisors to Estimate Support for Job Accommodations

Appendix: The Standard Case Vignette for Supervisors to Estimate Support for Job Accommodations

Imagine a 38-year old worker (Robert) that you supervise, who is employed as a------------- This morning, Robert experienced a sudden onset of back pain while maneuvering some equipment in the workplace. You recommended that Robert see a doctor, who told him that his pain was due to a back sprain caused by overexertion. Before the physician can make a formal recommendation about Robert’s return to work, he needs some advice from the company on what types of job modifications are typical for your work setting. Robert took the day off to rest and recover, but he will return to work tomorrow morning if it’s possible to temporarily modify his job responsibilities to reduce discomfort. Robert has no prior sickness absence due to back pain.

You have been asked by the company to suggest possible job modifications that would allow Robert to return to modified duty, but the job modifications should be easy for you to arrange with no substantial reduction in your group’s productivity or undue burden to other workers. Also, the job modifications should be changes that Robert would appreciate as helpful, without him feeling embarrassed or undervalued. You can presume that any job modifications would be in effect for at least 2 weeks.

On the following screen, you will be provided a list of possible job modifications to choose from. Based on the circumstances of this case, the typical practices in your organization, your usual supervisory demands, and the job requirements of this position, how likely is it that you would have recommended each of the following job modifications in Robert’s case?

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shaw, W.S., Kristman, V.L., Williams-Whitt, K. et al. The Job Accommodation Scale (JAS): Psychometric Evaluation of a New Measure of Employer Support for Temporary Job Modifications. J Occup Rehabil 24, 755–765 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-014-9508-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-014-9508-7