Abstract

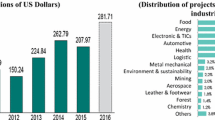

Much in line with what has been happening in developed economies for the past few decades, policy decision makers and industry strategists in developing countries have dedicated increased attention to initiatives that foster University-Industry Collaboration (UIC). The overarching goal is to enhance the capabilities/efficiencies of innovation systems, leveraging the role of universities as generators and disseminators of valuable knowledge, highly concentrated in academia in these laggard nations. In this article we empirically assess the extent to which institutional openness in universities towards UIC linkages affect the generation of knowledge-intensive spin-offs and academic patenting activity in the context of the State of São Paulo, Brazil. We use data for 462 knowledge-intensive entrepreneurial projects related to academics receiving grants from the PIPE Program of the State of São Paulo, Brazil, as well as international patenting behavior for 126 universities and research institutes. Additionally, we have gathered data for UIC activity (2002–2010) in the affected region. The main novelty of our approach is to qualify UIC according to three different dimensions of openness, focusing on UIC levels and objects of collaboration. Results suggest that the quality of linkages (collaboration content) is a stronger predictor of both types of university entrepreneurship than the extent to which universities are connected to firms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Hirsch-Kreinsen and Schwinge (2014) define KIE as an entrepreneurial activity involving the market exploitation of new opportunities, which can be carried out by individuals or established organizations. These ventures are likely to have significant impacts upon economic growth, social welfare and wealth creation (Beckman et al. 2012).

Illustratively, Schartinger et al. (2002) classify types UIC into four groups: (i) joint research; (ii) contract research; (iii) personnel mobility; and (iv) training activities. In Brazil, UIC can be classified according to fourteen groups, ranging from basic and applied scientific research to material supply and outsourced training activities.

Even though the vast majority of institutions in our sample consist in universities, there are also several research institutes. Following the extant literature on UIC, we adopt a flexible view of the term “university” to also include these additional cases. Hence, whenever we refer to UIC (or universities as a whole), research institutes are part of the discussion (Cohen et al. 2002; Zawislak and Dalmarco 2011)..

Additional possibilities of time lags are taken into account in econometric models, aiming at identifying longer-term connections between university openness and academic entrepreneurship..

This database is maintained by the Brazilian Council for Scientific and Technological Development and registration is required for scholars (professors, researchers and students)..

We would like to thank Chris Hayter for pointing this out.

Some caution must be taken for the appropriation of estimations in Models 9–14. Patents might also be somewhat associated with institutional size, and in the absence of a proper size control it is difficult to disentangle these effects. Nonetheless, other variables also help to control for size effects (Res_Intensity and Entrep_Infra), thus helping to control for potential instabilities in the model.

This variable also functions as a proxy for institutional size, as most science parks and incubators are associated with large universities.

As per the roles of TTOs in Brazil, providing support for patent registration is more in line with these offices’ remit than developing external business opportunities for academic entrepreneurs.

We would like to thank Professor Jeewhan Yoon for highlighting the importance of this discussion.

This institutional background is mandatory only to public universities and research institutes. Nonetheless, in Brazil, these units respond for most of cutting-edge research and represent the main generators of academic spin-offs in our sample.

References

Abereijo, I. (2015). Transversing the “valley of death”: understanding the determinants to commercialisation of research outputs in Nigeria. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 6(1), 90–106.

Abreu, M., & Grinevich, V. (2013). The nature of academic entrepreneurship in the UK: Widening the focus on entrepreneurial activities. Research Policy, 42(2), 408–422.

Agrawal, A. (2001). University-to-industry knowledge transfer: Literature review and unanswered questions. International Journal of Management Reviews, 3(4), 285–302.

Arocena, R., & Sutz, J. (2001). Changing knowledge production in Latin American universities. Research Policy, 30(8), 1221–1234.

Arvanitis, S., Kubli, U., & Woerter, M. (2008). University-industry knowledge and technology transfer in Switzerland: What university scientists think about co-operation with private enterprises. Research Policy, 37(10), 1865–1883.

Arza, V. (2010). Channels, benefits and risks of public-private interactions for knowledge transfer: conceptual framework inspired by Latin America. Science and Public Policy, 37(7), 473–484.

Audretsch, D., Kuratko, D., Link, A. (2016). Dynamics entrepreneurship and technology-based innovation. [Working Paper 16-02]. The University of North Carolina, Department of Economics Working Paper Series.

Beckman, C., Eisenhardt, K., Kotha, S., Meyer, A., & Rajagopalan, N. (2012). Technology entrepreneurship. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 6(2), 89–93.

Bercovitz, J., & Feldman, M. (2006). Entrepreneurial universities and technology transfer: A conceptual framework for understanding knowledge-based economic development. Journal of Technology Transfer, 31(1), 175–188.

Birley, S. (1985). The role of networks in the entrepreneurial process. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(1), 107–117.

Boh, W., De-Haan, U., & Strom, R. (2016). University technology transfer through entrepreneurship: Faculty and students in spinoffs. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 41(4), 661–669.

Bonaccorsi, A., & Piccaluga, A. (1994). A theoretical framework for the evaluation of university-industry relationships. R&D Management, 24(3), 229–247.

Brown, R. (2016). Mission impossible? Entrepreneurial universities and peripheral innovation systems. Industry and Innovation, 23(2), 1–17.

Caloghirou, Y., Tsakanikas, A., & Vonortas, N. (2001). University-industry cooperation in the context of the European Framework Programmes. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 26(1), 153–161.

Chesbrough, H. (2003). The era of open innovation. MIT Sloan Management Review, 44(3), 35–41.

Cohen, W., Nelson, R., & Walsh, J. (2002). Links and impacts: the influence of public research on industrial R&D. Management Science, 48(1), 1–23.

Colyvas, J., Crow, M., Gelijns, A., Mazzoleni, R., Nelson, R., Rosenberg, N., et al. (2002). How do university inventions get into practice? Management Science, 48(1), 61–72.

Cowan, R., & Zinovyeva, N. (2013). University effects on regional innovation. Research Policy, 42(3), 788–800.

Czarnitzki, D., Doherr, T., Hussinger, K., Schliessler, P., Toole, A. (2016). Knowledge creates markets: The influence of entrepreneurial support and patent rights on academic entrepreneurship. [Discussion Paper n. 16-036]. Center for European Economic Research.

Di Gregorio, D., & Shane, S. (2003). Why do some universities generate more start-ups than others? Research Policy, 32(2), 209–227.

Dietz, J., & Bozeman, B. (2005). Academic careers, patents, and productivity: Industry experience as scientific and technical human capital. Research Policy, 34(3), 349–367.

Dorfman, N. (1983). Route 128: The development of a regional high technology economy. Research Policy, 12(6), 299–316.

Etzkowitz, H. (1998). The norms of entrepreneurial science: Cognitive effects of the new university-industry linkages. Research Policy, 27(8), 823–833.

Etzkowitz, H. (2004). The evolution of the entrepreneurial university. International Journal of Technology and Globalisation, 1(1), 64–77.

Etzkowitz, H., & Leydesdorff, L. (2000). The dynamics of innovation: From National Systems and ‘‘Mode 2’’ to a Triple Helix of university–industry–government relations. Research Policy, 29(2), 109–123.

Fernandes, A., Souza, B., Silva, A., Suzigan, W., Chaves, C., & Albuquerque, E. (2010). Academy-industry links in Brazil: Evidence about channels and benefits for firms and researchers. Science and Public Policy, 37(7), 485–498.

Goel, R., & Grimpe, C. (2012). Are all academic entrepreneurs created alike? Evidence from Germany. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 21(3), 247–266.

Gras, J., Lapera, D., Solves, I., Jover, A., & Azuar, J. (2008). An empirical approach to the organisational determinants of spin-off creation in European universities. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 4(2), 187–198.

Gulbrandsen, M., & Smeby, J. (2005). Industry funding and university professors’ research performance. Research Policy, 34(6), 932–950.

Hayter, C. (2016). Constraining entrepreneurial development: A knowledge-based view of social networks among academic entrepreneurs. Research Policy, 45(2), 475–490.

Hirsch-Kreinsen, H., & Schwinge, I. (2014). Knowledge-intensive entrepreneurship in low-tech industries. London: Edward Elgar.

Karnani, F. (2012). The university’s unknown knowledge: Tacit knowledge, technology transfer and university spin-offs findings from an empirical study based on the theory of knowledge. Journal of Technology Transfer, 38(3), 235–250.

Kenney, M., & Patton, D. (2005). Entrepreneurial geographies: Support networks in three high-technology industries. Economic Geography, 81(2), 201–228.

Krabel, S., & Mueller, P. (2009). What drives scientists to start their own company? An empirical investigation of Max Planck Society scientists. Research Policy, 38(6), 947–956.

Landry, R., Amara, N., & Ouimet, M. (2007). Research transfer in natural science and engineering: Evidence from Canadian universities. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 32(6), 561–592.

Landry, R., Amara, N., & Rherrad, I. (2006). Why are some university researchers more likely to create spin-offs than others? Evidence from Canadian universities. Research Policy, 35(10), 1599–1615.

Lederman, D., Messina, J., Pienknagura, S., & Rigolini, J. (2014). Latin American entrepreneurs: Many firms but little innovation. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Lee, Y. (2000). The sustainability of university-industry research collaboration: An empirical assessment. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 25(2), 111–133.

Lee, K., Lim, G., & Tan, S. (1999). Dealing with resource disadvantage: Generic strategies for SMEs. Small Business Economics, 12(4), 299–311.

Lockett, A., & Wright, M. (2005). Resources, capabilities, risk capital and the creation of university spin-out companies. Research Policy, 34(7), 1043–1057.

Lockett, A., Wright, M., & Franklin, S. (2003). Technology transfer and universities’ spin-out strategies. Small Business Economics, 20(2), 185–200.

Looy, B., Landoni, P., Callaert, J., van Pottelsberghe, B., Sapsalis, E., & Debackere, K. (2011). Entrepreneurial effectiveness of European universities: An empirical assessment of antecedents and trade-offs. Research Policy, 40(4), 553–564.

Meyer-Krahmer, F., & Schmoch, U. (1998). Science-based technologies: university-industry interactions in four fields. Research Policy, 27(8), 835–851.

Moutinho, R., Au-Yong-Oliveira, M., Coelho, A., & Manso, J. (2014). Determinants of knowledge-based entrepreneurship: An exploratory approach. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12(1), 171–197.

Neves, M., & Franco, M. (2016). Academic spin-off creation: Barriers and how to overcome them. R&D Management. doi:10.1111/radm.12231.

Nicolaou, N., & Birley, S. (2003). Social networks in organizational emergence: The university spinout phenomenon. Management Science, 49(12), 1702–1726.

O’Shea, R., Allen, T., Chevalier, A., & Roche, F. (2005). Entrepreneurial orientation, technology transfer and spinoff performance of U.S. universities. Research Policy, 34(7), 994–1009.

Padilla-Meléndez, A., & Garrido-Moreno, A. (2012). Open innovation in universities. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research, 18(4), 417–439.

Pascoe, C., & Vonortas, N. S. (2015). University entrepreneurship: A survey of US experience. In N. S. Vonortas, P. Rouge, & A. Aridi (Eds.), Innovation policy: A practical introduction. New York: Springer.

Perkmann, M., Tartari, V., McKelvey, M., Autio, E., Broström, A., D’Este, P., et al. (2013). Academic engagement and commercialisation: A review of the literature on university–industry relations. Research Policy, 42(2), 423–442.

Perkmann, M., & Walsh, K. (2007). University–industry relationships and open innovation: Towards a research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 9(4), 259–280.

Pfirrmann, O. (1998). Small firms in high-tech: A European analysis. Small Business Economics, 10(3), 227–241.

Powers, J., & McDougall, P. (2005). University start-up formation and technology licensing with firms that go public: A resource-based view of academic entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(3), 291–311.

Rapini, M., Albuquerque, E., Chave, C., Silva, L., Souza, S., Righi, H., et al. (2009). University-industry interactions in an immature system of innovation: evidence from Minas Gerais. Brazil. Science and Public Policy, 36(5), 373–386.

Rasmussen, E., Mosey, S., & Wright, M. (2014). The influence of university departments on the evolution of entrepreneurial competencies in spin-off ventures. Research Policy, 43(1), 92–106.

Roshani, M., Lehoux, N., Frayret, J. (2015). University-Industry collaborations and open innovations: An integrated methodology for mutually beneficial relationships. [Working Paper 2015-22]. Centre Interuniversitaire de Recherche sur les Réseaux d’Enterprise, la Logistique et le Transport—CIRRELT.

Salimi, N., Bekkers, R., & Frenken, K. (2015). Does working with industry come at a price? A study of doctoral candidates’ performance in collaborative vs. non-collaborative PhD projects. Technovation, 41–42, 51–61.

Salles-Filho, S., Bonacelli, M., Carneiro, A., Castro, P., & Santos, F. (2011). Evaluation of ST&I programs: A methodological approach to the Brazilian Small Business Program and some comparisons with the SBIR program. Research Evaluation, 20(2), 157–169.

Schartinger, D., Rammer, C., Fischer, M., & Frölich, J. (2002). Knowledge interactions between universities and industry in Austria: Sectoral patterns and determinants. Research Policy, 31(3), 303–328.

Shane, S., & Stuart, T. (2002). Organizational endowments and the performance of university start-ups. Management Science, 48(1), 154–170.

Siegel, D., Waldman, D., Atwater, L., & Link, A. (2003). Commercial knowledge transfers from universities to firms: Improving the effectiveness of university–industry collaboration. The Journal of High Technology Management Research, 14(1), 111–133.

Stam, E. (2009). Entrepreneurship, evolution and geography. [Papers in evolutionary economic geography]. Utrecht University—Urban and Regional Research Centre.

Striukova, L., & Rayna, T. (2015). University-industry knowledge exchange. European Journal of Innovation Management, 18(4), 471–492.

Stuart, T., & Ding, W. (2006). When do scientists become entrepreneurs? The social structural antecedents of commercial activity in the academic life sciences. American Journal of Sociology, 112(1), 97–144.

Tether, B. (2002). Who co-operates for innovation, and why. Research Policy, 31(6), 947–967.

Thursby, J., & Thursby, M. (2002). Who is selling the ivory tower? Sources of growth in university licensing. Management Science, 48(1), 90–104.

Walter, A., Auer, M., & Ritter, T. (2006). The impact of network capabilities and entrepreneurial orientation on university spin-off performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(4), 541–567.

Zawislak, P., & Dalmarco, G. (2011). The silent run: new issues and outcomes for university-industry relations in Brazil. Journal of Technology Management and Innovation, 6(2), 66–82.

Zucker, L., & Darby, M. (2001). Capturing technological opportunity via Japan’s star scientists: Evidence from Japanese firms’ biotech patents and products. Journal of Technology Transfer, 26(1), 37–58.

Zucker, L., Darby, M., & Armstrong, J. (2002). Commercializing knowledge: university science, knowledge capture, and firm performance in biotechnology. Management Science, 48(1), 138–153.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) in connection to the São Paulo Excellence Chair in innovation systems, strategy and policy established in the Department of Science and Technology Policy of the University of Campinas (UNICAMP). Bruno Fischer and Paola Schaeffer also recognize FAPESP support under the project The Economic Geography of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems in the State of São Paulo (2016/17801-4). Nicholas Vonortas acknowledges the infrastructural support of the Center for International Science and Technology Policy at the George Washington University. He also acknowledges the support of FAPESP through the São Paulo Excellence Chair in technology and innovation policy at Unicamp, Brazil. And, he acknowledges support from the Basic Research Program at the National Research University Higher School of Economics within the framework of the subsidy to the HSE by the Russian Academic Excellence Project ‘5–100’. None of these organizations are responsible for the contents of this paper. Remaining mistakes and misconceptions are solely the responsibility of the author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

See Table 6.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fischer, B.B., Schaeffer, P.R., Vonortas, N.S. et al. Quality comes first: university-industry collaboration as a source of academic entrepreneurship in a developing country. J Technol Transf 43, 263–284 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-017-9568-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-017-9568-x