Abstract

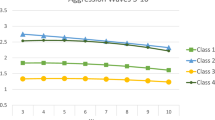

Despite decades of study, no scholarly consensus has emerged regarding whether violent video games contribute to youth violence. Some skeptics contend that small correlations between violent game play and violence-related outcomes may be due to other factors, which include a wide range of possible effects from gender, mental health, and social influences. The current study examines this issue with a large and diverse (49 % white, 21 % black, 18 % Hispanic, and 12 % other or mixed race/ethnicity; 51 % female) sample of youth in eighth (n = 5133) and eleventh grade (n = 3886). Models examining video game play and violence-related outcomes without any controls tended to return small, but statistically significant relationships between violent games and violence-related outcomes. However, once other predictors were included in the models and once propensity scores were used to control for an underlying propensity for choosing or being allowed to play violent video games, these relationships vanished, became inverse, or were reduced to trivial effect sizes. These results offer further support to the conclusion that video game violence is not a meaningful predictor of youth violence and, instead, support the conclusion that family and social variables are more influential factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Senator Clinton presented this statement as a quote of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) via a report entitled Media Exposure Feeding Children’s Violent Acts. The quote, however, actually appeared in news coverage (O’Keefe 2002), but did not appear in the original article by the AAP. To be sure, the article being reported on did make the claim that the effect was stronger than smoke on lung cancer (American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Public Education 2001), which reached that conclusion using evidence without citations from a prepared statement given during testimony before congress (Committee on Commerce Science and Transportation 2000).

Although the questionnaire included several deviance-related questions, these two were the only ones that directly measured violence against another person.

Only 12% of eighth grade students and 10% of eleventh grade students selected the highest category. Therefore, it appears that only minimal information about a greater range was lost given the “or more” nature of this response category.

The reason this kitchen sink approach is often used is because the utility from propensity scores comes from having as accurate a score as possible through a model capable of predicting the variable of interest. The number of indicators, because they are reduced down via regression weights into a single score, is largely irrelevant other than that more variables will (usually) produce a more accurate score. In other words, a variable does not require a clear theoretical, direct, or non-spurious connection in order to be useful in creating a propensity score and regression assumptions are of reduced concern (Wooldridge 2010). In respect to maintaining time-order, however, the present study avoids using variables that could be outcomes from playing violent games.

Prior research has found substantial gender differences (e.g., DeCamp 2015; Gunter and Daly 2012), so separate models for males and females are necessary. Although there is no similar evidence of a difference between grades, we err on the side of caution in the absence of evidence to the contrary and do not merge the distinct grade samples.

References

Adachi, P. C., & Willoughby, T. (2013). Demolishing the competition: the longitudinal link between competitive video games, competitive gambling, and aggression. Journal Of Youth And Adolescence, 42(7), 1090–1104. doi:10.1007/s10964-013-9952-2.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Public Education. (2001). Media violence. Pediatrics, 108, 1222–1226.

Anderson, C. A., Shibuya, A., Ihori, N., Swing, E. L., Bushman, B. J., Sakamoto, A., & Saleem, M. (2010). Violent video game effects on aggression, empathy, and prosocial behavior in Eastern and Western countries: a meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 136(2), 151–173. doi:10.1037/a0018251.

Bandura, A., Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. (1963). Imitation of film-mediated aggressive models. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 66(1), 3.

Breuer, J., Vogelgesang, J., Quandt, T., & Festl, R. (2015). Violent video games and physical aggression: evidence for a selection effect among adolescents. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 4(4), 305–328. doi:10.1037/ppm0000035.

Bushman, B. J., & Huesmann, L. (2014). Twenty-five years of research on violence in digital games and aggression revisited: a reply to Elson and Ferguson (2013). European Psychologist, 19(1), 47–55. doi:10.1027/1016-9040/a000164.

Caspi, A., McClay, J., Moffitt, T. E., Mill, J., Martin, J., Craig, I. W., & Poulton, R. (2002). Role of genotype in the cycle of violence in maltreated children. Science, 297, 851–854.

CBS News. (2005). Senator Clinton on Violent Games. CBS News. Retrieved from: http://www.cbsnews.com/news/senator-clinton-on-violent-games/.

Clinton, H. (2005). Statements on Introduced Bills and Joint Resolutions. Retrieved from: https://votesmart.org/public-statement/143073/statements-on-introduced-bills-and-joint-resolutions.

CNN. (1997). Senator decries violent video games. CNN. Retrieved from: http://edition.cnn.com/ALLPOLITICS/1997/11/25/email/videos/.

Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation. (2000). The Impact of Interactive Violence on Children: Hearing Before the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, United States Senate. Retrieved from: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG-106shrg78656/pdf/CHRG-106shrg78656.pdf.

Cunningham, S., Engelstatter, B., & Ward, M. (2016). Violent video games and violent crime. Southern Economic Journal, 82, 1247–1265.

DeCamp, W. (2015). Impersonal agencies of communication: comparing the effects of video games and other risk factors on violence. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 4, 296–304. doi:10.1037/ppm0000037.

DeCamp, W., & Zaykowski, H. (2015). Developmental victimology estimating group victimization trajectories in the age–victimization curve. International Review of Victimology, 21(3), 255–272. doi:10.1177/0269758015591722.

Elson, M., Mohseni, M. R., Breuer, J., Scharkow, M., & Quandt, T. (2014). Press CRTT to measure aggressive behavior: the unstandardized use of the competitive reaction time task in aggression research. Psychological Assessment, 26(2), 419–432. doi:10.1037/a0035569.

Ferguson, C. J. (2015a). Does movie or videogame violence predict societal violence? It depends on what you look at and when. Journal of Communication, 65, 193–212.

Ferguson, C. J. (2015b). Do angry birds make for angry children? A meta-analysis of video game influences on children’s and adolescents’ aggression, mental health, prosocial behavior and academic performance. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10, 646–666.

Ferguson, C. J., & Beaver, K. M. (2009). Natural born killers: the genetic origins of extreme violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 14(5), 286–294.

Gottfredson, M. R., &Hirschi, T. (1990). A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press.

Gunter, WhitneyD., & Daly., Kevin (2012). Causal or spurious: using propensity score matching to detangle the relationship between violent video games and violent behavior. Computers in Human Behavior, 28, 1348–1355. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.02.020.

Hirschi, T. (1969). The causes of delinquency. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lauritsen, J. L., & Laub, J. H. (2007). Understanding the link between victimization and offending: new reflections on an old idea. Crime Prevention Studies, 22, 55.

Li, J., & Jin, Y. (2014). The effects of violent video games and prosocial video games on cognition, emotion and behavior. Chinese Journal Of Clinical Psychology, 22(6), 985–988.

Markey, P. M., Males, M. A., French, J. E., & Markey, C. N. (2015). Lessons from Markey et al. (2015) and Bushman et al. (2015): Sensationalism and integrity in media research. Human Communication Research, 41(2), 184–203. doi:10.1111/hcre.12057.

Markey, P. M., Markey, C. N., & French, J. E. (2015). Violent video games and real-world violence: rhetoric versus data. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 4(4), 277–295. doi:10.1037/ppm0000030.

Merritt, A., LaQuea, R., Cromwell, R., & Ferguson, C. J. (2016). Media managing mood: a look at the possible effects of violent media on affect. Child & Youth Care Forum, 45(2), 241–258. doi:10.1007/s10566-015-9328-8.

O’Keefe, L. (2002). Media exposure feeding children’s violent acts, AAP policy states. AAP News.

Olson, C. K. (2010). Children’s motivations for video game play in the context of normal development. Review of General Psychology, 14(2), 180–187.

Piquero, A. R., & Weisburd, D. (2010). Handbook of quantitative criminology. New York: Springer.

Pratt, T., Cullen, F., Sellers, C., Winfree, T., Madensen, T., & Daigle, L., et al. (2010). The empirical status of social learning theory: a meta-analysis. Justice Quarterly, 27, 765–802.

Przybylski, A. K. (2014). Electronic gaming and psychosocial adjustment. Pediatrics, 134(3), e716–e722. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-4021.

Przybylski, A. K., Deci, E. L., Rigby, C. S., & Ryan, R. M. (2014). Competence-impeding electronic games and players’ aggressive feelings, thoughts, and behaviors. Journal Of Personality And Social Psychology, 106(3), 441–457. doi:10.1037/a0034820.

Przybylski, A. K., & Mishkin, A. F. (2016). How the quantity and quality of electronic gaming relates to adolescents’ academic engagement and psychosocial adjustment. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 5(2), 145–156. doi:10.1037/ppm0000070.

Przybylski, A. K., Rigby, C. S., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). A motivational model of video game engagement. Review Of General Psychology, 14(2), 154–166. doi:10.1037/a0019440.

Savage, J., & Yancey, C. (2008). The effects of media violence exposure on criminal aggression: a meta-analysis. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 35, 1123–1136.

Schwartz, J., & Beaver, K. (2016). Revisiting the association between television viewing in adolescence and contact with the criminal justice system in adulthood. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31, 2387–2411.

Sherry J. (2007). Violent video games and aggression: Why can’t we find links? In R. Preiss, B. Gayle, N. Burrell, M. Allen, & J. Bryant, (Eds.), Mass media effects research: advances through meta-analysis (pp. 231-248). Mahwah, NJ: L. Erlbaum.

Slater, M. D., Henry, K. L., Swaim, R. C., & Anderson, L. L. (2003). Violent media content and aggressiveness in adolescents: a downward spiral model. Communication Research, 30(6), 713–736. doi:10.1177/0093650203258281.

Strasburger, V. C. (2007). Go ahead punk, make my day: it’s time for pediatricians to take action against media violence. Pediatrics, 119, e1398–e1399.

Surette, R. (2013). Cause or catalyst: the interaction of real world and media crime models. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 38, 392–409. doi:10.1007/s12103-012-9177-z.

Surette, R., & Maze, A. (2015). Video game play and copycat crime: an exploratory analysis of an inmate population. Psychology Of Popular Media Culture, doi: 10.1037/ppm0000050.

Sutherland, E. H., & Cressey, D. R. (1960/2007). A theory of differential association. In R. D. Crutchfield, C. E. Kubrin, G. S. Bridges, & J. G.Weis (Eds.), Crime: readings (3rd edn., pp. 224–225). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. (Original work published 1960).

Szycik, G. R., Mohammadi, B., Hake, M., Kneer, J., Samii, A., Münte, T. F., & Wildt, B. T. (2016). Excessive users of violent video games do not show emotional desensitization: an fmri study. Brain Imaging And Behavior. doi:10.1007/s11682-016-9549-y.

Woolley, J. D., & Van Reet, J. (2006). effects of context on judgments concerning the reality status of novel entities. Child Development, 77(6), 1778–1793. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00973.x.

von Salisch, M., Vogelgesang, J., Kristen, A., & Oppl, C. (2011). Preference for violent electronic games and aggressive behavior among children: the beginning of the downward spiral? Media Psychology, 14(3), 233–258. doi:10.1080/15213269.2011.596468.

Wallenius, M., & Punamäki, R. (2008). Digital game violence and direct aggression in adolescence: a longitudinal study of the roles of sex, age, and parent-child communication. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 29(4), 286–294. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2008.04.010.

Ward, M. R. (2010). Video games and adolescent fighting. Journal of Law & Economics, 53, 611–628.

Widom, C. S. (1989). Does violence beget violence? A critical examination of the literature. Psychological Bulletin, 106(1), 3.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT Press: Cambridge, MA.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the anonymous peer reviewers for their helpful insights and contributions to this work.

Authors’ Contributions

WD conceived of the study, obtained the data, participated in the design, conducted some statistical analyses, and drafted some sections of the manuscript; CF participated in the design, conducted some statistical analyses, and drafted some sections of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study received no grants or funding. The data used in this research were collected by the University of Delaware Center for Drug and Health Studies as part of a project supported by the Delaware Health Fund and by the Division of Substance Abuse and Mental Health, DE Health and Social Services.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The data used in this study were collected under a protocol approved by the University of Delaware Institutional Review Board.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Appendix

Appendix

Indicators used in propensity score construction

The following is a list of variables used for the construction of the propensity scores. Some of these are multiple response questions, resulting in a total of 171 indicators (counting each mark all that apply response separately) used. Exact question wording and response categories are available from the authors upon request.

Free-lunch; age; gender; race and ethnicity; are either of your parents or other adults (18 years or older) in your family serving on active duty in the military?; which of the following people live with you most of the time? (list of family member-relations); which of the people who live with you right now work to earn money to pay the bills and buy the food? (same list as previous); how old is your mother?; how old is your father?; what is the highest level of schooling your mother or female guardian completed?; what is the highest level of schooling your father or male guardian completed?; have you been identified by a doctor or other health-care professional as having difficulty concentrating, remembering, making decisions or doing things because of a physical, learning, or emotional disability? (list of disabilities); has your family experienced any of the following in the past year? (list of economic hardship indicators); have you had lessons in school about…? (substance use education and healthy relationships); have any of your family members been incarcerated (in a prison or detention center) in the past year? (list of family member-relations); how much schooling do you think you will complete?; are you deaf or do you have serious difficulty hearing?; do you have serious difficulty seeing, even when wearing glasses?; because of a physical, mental, or emotional condition, do you have serious difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions?; do you have serious difficulty walking or climbing stairs?; my parents know where I am when I am not in school; I feel safe in my neighborhood; I feel safe in my school; teachers here treat students with respect; I get along well with my parents/guardians; students here treat teachers with respect; students in this school are well-behaved in public (classes, assemblies, cafeterias); student violence is a problem at this school; school rules are fair; school rules are strictly enforced; my parents’/guardians’ rules are strictly enforced; how often do you hear name-calling, threats or yelling between adults in your home that makes you feel bad?; hear or see violence between adults in your home?; see or hear a media message about the risks of teens drinking alcohol?; does anybody living in your home smoke cigarettes, cigars, little cigars, pipe or other tobacco products? (list of family member-relations); if you wanted to get cigarettes, where would you most likely get them? (list of relationships); do you take any medicine by prescription to help you concentrate better in school?; do you take any medicine by prescription for any of the following? (list of conditions); I know where students my age can buy… (list of substances); how much do people risk harming themselves (physically and other ways) when they: (list of substances and amounts); how often do you: get hit by an adult who intends to hurt you?; get hit by another teen with the intention of hurting you?; see crime in your neighborhood?; see drug sales in your neighborhood?; get bullied in your neighborhood?; get threatened or harassed electronically?; which of the following people give you a lot of support and encouragement? (list of relationships); which of the following are true for you? (statements about being able to trust and help people); during an average week, do you participate in organized activities at any of the following? (list of clubs and organizations); my parent/guardian shows me they are proud of me; my parent/guardian takes an interest in my activities; my parent/guardian listens to me when I talk to them; I can count on my parent/guardian to be there when I need them; my parent/guardian and I talk about the things that really matter; I am comfortable sharing my thoughts and feelings with my parent/guardian; how often did you feel really sad?; how often did you feel really worried?; how often did you feel afraid?; how often did you have trouble relaxing?; how often did you feel nervous?; how much time do you spend on a school day (before and after school): online on a computer (not for school work), tablet, phone, watching TV, or playing computer/video games?; doing school work at home?; reading for pleasure (not a school assignment)?; during the past 7 days: how many times did you drink 100 % fruit juices such as orange juice, apple juice or grape juice?; how many times did you eat fruit?; how many times did you eat green salad?; how many times did you eat other vegetables?; how many times did you drink a can, bottle, or glass of soda or pop, such as Coke, Pepsi, or Sprite?; how many glasses of milk did you drink?; how many times did you drink a caffeinated drink such as coffee, tea, sodas, power drinks, energy drinks, or other drinks with caffeine added?; on an average school night, how many hours of sleep do you get?; how many text messages do you send on an average day?; how many days in an average week do you eat breakfast?; during the past 7 days, on how many days were you physically active for a total of at least 60 min per day?; in the past year, my parents have (list of positive and negative parental activities)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

DeCamp, W., Ferguson, C.J. The Impact of Degree of Exposure to Violent Video Games, Family Background, and Other Factors on Youth Violence. J Youth Adolescence 46, 388–400 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0561-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0561-8