Abstract

A new measure of credibility is constructed as a function of the differential between observed inflation and some estimate of the inflation rate that the central bank targets. The target is assumed to be met flexibly. Credibility is calculated for a large group of both advanced and emerging countries from 1980 to 2014. Financial crises reduce central bank credibility and central banks with strong institutional feaures tend to do better when hit by a shock of the magnitude of the 2007-2008 financial crisis. The VIX, adopting an inflation target and central bank transparency, are the most reliable determinants of credibility. Similarly, real economic growth has a significant influence on central bank credibility even in inflation targeting economies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Regressions in Bordo and Siklos (2016) show that key determinants of credibility include the policy regime followed (especially the gold standard), central bank independence from the fiscal authorities and financial crises. Since the 1980s credibility has been enhanced by adhering to inflation targeting (IT) which is associated with better communication and transparency.

In Bordo and Siklos (2014), owing to the absence of market-based measures of inflationary expectations, our credibility indicator was derived from a reduced form expression based on a small structural model.

That said, an important limitation of these institutional variables, important as they are, is that they change very slowly and the requisite data are available either at the annual or even decanal sampling frequencies. Moreover, even at the annual frequency, data for all the economies in our dataset are not available. A case in point is an indicator of central bank transparency (CBI; e.g., see Eijfinger and Geraats (2006); Dincer and Eichengreen 2014). Furthermore, the sample for the bulk of the economies in this study where CBI night well have played an important role is short enough such that there is insufficient variation in existing CBI indicators to render them empirically useful.

In some cases the data were not available from the IMF’s International Financial Statistics; in a few other cases the available samples were so short that it did not seem practical to collect the available data.

For several emerging or developing economies the data were initially published on a bi-monthly basis. Eventually, the data were published monthly. Bi-monthly data were converted into monthly data via interpolation using the Catmull-Rom spline algorithm.

See Siklos (2013), and references therein, for discussion. If monthly inflation is denoted by π the transformation is as follows: \( {\pi}_{m,t}^{FH}=\left[\left(13-m\right)/12\right]{\pi}_t^{FE}+\left[\left(m-1\right)/12\right]{\pi}_{m,t+1}^{FE} \) where \( {\pi}_{m,t}^{FE},{\pi}_{m,t}^{FH} \) are, respectively, fixed event (FE) and fixed horizon (FH) forecasts, at time t, in month m. The same transformation is used to create fixed horizon real GDP growth forecasts.

Observed inflation data are also generally available at the monthly frequency. Australia and New Zealand are two notable exceptions since they publish only quarterly data.

A positive change in the real exchange rate is defined as a real appreciation.

It was pointed out to us that not all central banks supervise the financial system. Hence, it is unclear why the capital-asset ratio should be considered a determinant of central bank credibility. This variable is a proxy for financial stability and even if the central bank does not directly supervise the banking system almost all central banks are expected (whether explicitly or not) to ensure financial system stability.

Only a small number of central banks relative to the size of our data set have created indexes of financial stress or stability by combining a large number of related factors.

http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/index.aspx#home. Voice and accountability is defined as “capturing perceptions of the extent to which a country’s citizens are able to participate in selecting their government, as well as freedom of expression, freedom of association, and a free media.” Rule of law represents “…perceptions of the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society, and in particular the quality of contract enforcement, property rights, the police, and the courts, as well as the likelihood of crime and violence.” Political stability captures “perceptions of the likelihood that the government will be destabilized or overthrown by unconstitutional or violent means, including politically-motivated violence and terrorism.” See Kaufmann et al. (2010. pg. 4).

We also considered Heritage Foundation’s index of economic freedom or fiscal freedom (http://www.heritage.org/). Economic freedom is based on a grouping of 10 quantitative and qualitative factors that include the rule of law, property rights, regulatory efficiency and trade openness. A more complete definition is available at http://www.heritage.org/index/about. Fiscal freedom is an aggregation of three indicators, namely the top marginal tax rate on individual income, the top marginal tax rate on corporate income, and the total tax burden as a percent of GDP. More details are available at http://www.heritage.org/index/fiscal-freedom. The conclusions discussed below were largely unaffected when data from this source was included. Hence, their use is not discussed further.

It was pointed out to us that exchange rate management is also likely part of the several central bank loss functions. Clarida (2001), and Collins and Siklos (2004), for example, demonstrate empirically and via simulation exercises that the traditional loss function is not significantly improved by the explicit addition of a real exchange rate objective. Nevertheless, as noted above, the real exchange rate is included as a separate determinant of credibility.

Our conclusions were unaffected when we compare our gap estimates with ones, where available, generated from growth rate data. The one-sided filters were estimated twice holding either the first or last observation end-points fixed. In the case of estimates of the output gap we also examined the mean of the two one-sided estimates. The concern here is over the well-known end-point problem with traditional estimates that rely on an HP filter.

Central bank transparency data (up to 2011; data up to 2013 will be released shortly) are available from the Central Bank Communication Network http://www.central-bank-communication.net). The index aggregates 15 attributes which are then sub-divided into five broad categories. They are: political transparency, which measures how open the central bank is about its policy objectives; economic transparency, an indicator of the type of information used in the conduct of monetary policy; procedural transparency, which provides information about how monetary policy decisions are made; policy transparency, a measure of the content and how promptly decisions are made public by the central bank; and, finally, operational transparency, which summarizes how the central bank evaluates its own performance. Note also that central bank transparency and independence are not unrelated as Dincer and Eichengreen (2014) have pointed out.

The rise in transparency is not, however, solely associated with the formal adoption of numerical targets since the U.S., Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank (ECB), and the Swiss National Bank (SNB) are not, ordinarily, included among the group of inflation targeting economies even though they are considered to be central banks where inflation control is part of their remit.

In some of the estimated specifications we also include dummies for the GFC and the Asian Financial Crisis (AFC). The former is dated 2007Q1-2009Q4; the latter is set at one for the period 1997Q1-1998Q4.

In Bordo and Siklos (2016) the rule can be a Taylor rule, a money growth rule, or an exchange rate rule. The choice of rules depends on the policy regime actually in place. Otherwise, they are counterfactuals. In an appendix we present purely for illustrative purposes, central bank inflation targets estimated in Bordo and Siklos (2016) for 10 advanced economies since the early 1990s. Note that the model generated inflation objectives that the authors generated are based on annual, not monthly, data and over a much longer sample that the one examined below.

Several advanced economies only began to publish their own (or their staff’s) forecasts for inflation and real GDP growth in the early to mid-2000s. Indeed, many still report Consensus style forecasts when discussing the inflation outlook.

In most IT economies the target is often unchanged possibly after a gradual reduction of the target in the early years of such a regime. Hence, even in IT economies, there can be a backward0looking element to the target.

Since the calculations include contemporaneous inflation, a small forward-looking element remains in the estimates of the monetary authority’s inflation objective. There is usually a lag in the publication of current month or quarter inflation rates.

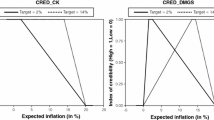

Note that \( {\pi}_t^{*} \) is not the mean inflation rate but an inflation objective as defined above. Hence, the second part of Eq. (1) is not the variance or a measure of inflation volatility.

For example, examining economies that adopted inflation targeting finds that only South Africa and Thailand specify target ranges that are slightly larger than the ± 1 % presumed in our calculations.

The relevance of this point is highlighted in recent discussions, mainly in some advanced economies, that inflation rates have been persistently below (or some years ago, persistently above) some inflation objective.

An example is when a central bank provides some information about the outlook or discusses the outlook as seen by other stakeholders (e.g., financial markets, professional forecasters).

We also considered oil prices (i.e., rate of change in either the Texas or Brent crude oil prices) but this variable was usually statistically insignificant. Hence, it is not discussed further.

It is true that the VIX includes an unobservable risk premium. An alternative, such as the volatility in some domestic financial asset price indicator (e.g., a stock market index) is equally plausible. However, resort to the VIX is ubiquitous in the literature. Hence, we retain this variable as a proxy for financial stability.

That is, we test whether the fixed effects are redundant or not. Owing to the limitations of the data a single lag of the right hand side variables serve as instruments. A panel version of the Stock and Yogo (2005) suggests that the chosen strategy is satisfactory.

Eurozone data is only used since the European Central Bank came into existence in 1998. All inflation forecasts and determinants of ECB credibility are also examined based on variables whose coverage only consists of the Eurozone (membership varies over time). See www.ecb.europa.eu/ecb/euro/intro/html/map.en.html.

In an earlier draft we also discussed real GDP growth (observed and forecasted) performance in the various country groupings examined. It is worth noting that forecasts in the Advanced economies are persistently downgraded relative to forecasts in the last years of the Great Moderation.

One possibility is that pass-through effects from commodity prices are relatively lower in emerging market economies that target inflation than in the other economies group shown in Fig. 1 (e.g., see Mihaljek and Klau 2008, Bussière and Peltonen 2008). In addition, the share of volatile prices (i.e., food and energy) in the CPI of the other economies is likely considerably higher than in the remaining economies considered in this study.

Recall that there were sharp increases in commodity prices beginning in 2007 and into 2008 which clearly spilled over into credibility losses.

The HKMA, of course, operates a pegged exchange rate regime. Therefore, it largely imparts US inflation throughout the sample. Nevertheless, the credibility of such a regime also rests on the inflationary consequences of the regime choice. After all, pass-through effects and other factors still create scope for an inflation differential vis-à-vis the US.

Based on the Im et al. (2003) panel unit root test, as well as the panel versions of the conventional ADF, and Phillips-Perron (PP) unit root tests.

As a robustness check we also estimated the relationships shown below for the full sample allowing for an “exogenous” break due to the GFC and the AFC. Again the main conclusions discussed below are unaffected. An alternative we did not implement is to rely on idiosyncratic dating for the global financial crisis (e.g., see Hashimoto et al. 2012) as opposed to assuming that the GFC’s duration is the same for every country.

We also generated estimates for the 2007Q1-2010Q4 sample (i.e., a ‘pure’ crisis sample) but these paralleled the results for the crisis/post-crisis sample shown in Table 1.

There was insufficient data to include a real exchange rate variable in the group of other economies considered.

Part of our findings might be due to the fact that we do not weight the economies by size or some other weighting scheme. Estimates using cross-section weights, however, did not change the conclusions.

There were too few observations to include a comparable series in the other cross-sections considered.

As mentioned previously, the adoption of inflation targeting (and its duration) seems roughly inversely proportional to the rise in central bank transparency. Indeed, when we replace an inflation targeting dummy with the overall indicator of central bank transparency we obtain comparable results. We do not pursue the possibility that the adoption of inflation targets and the rise of central bank transparency may interact with each other (or with some of the other right hand side variables, for that matter).

In the previous version of this paper results for the Advanced group of economies were shown but the G7 has the advantage of being a more homogeneous group.

These conclusions are based on Wald tests (not shown).

A separate list of the most and least credible central banks on an annual basis is relegated to an appendix (not shown).

Indeed, regressions suggest that the relative homogeneity of the G7 translates into more explanatory power. See Table 2.

References

Adrian T, Covitz D, and Liang N (2014) “Financial Stability Monitoring”, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report 601, June

Appelbaum B (2016) “Outspoken Fed Official Frets About Following Japan’s Path”, New York Times, 5 May

Bank for International Settlements (2015) 85th Annual Report (BIS: Basel, Switzerland).

Blinder A (2000) Central bank credibility: why do we care? How do we build it? Am Econ Rev 90:1421–1431

Bohl M, Siklos P, Werner T (2007) Do central banks react to the stock market? The case of the Bundesbank. J Bank Financ 31:719–733

Bohl M, Siklos P, Sondermann D (2008) European stock markets and ECB’s monetary policy surprises. Int Financ 11:117–130

Bordo MD (2014) “Rules for a Lender of Last Resort” in Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control. Special Issue: Frameworks for Central Banking in the Next Century: A Special Issue on the Occasion of the Centennial of the Founding of the Federal Reserve (guest editors: Michael D. Bordo, William Dupour and John B. Taylor), pp 126–125

Bordo MD, Siklos PL (2014) “Central Bank Credibility, Reputation and Inflation Targeting in Historical Perspective”, NBER working paper 20693, November

Bordo MD, Siklos PL (2016) “Central Bank Credibility and Reputation: An Historical Exploration”, NBER Working Paper 20824, January, forthcoming in Central Banks at a Crossroads: Lessons from History (M.D. Bordo, Øyvind Eitrheim, and M. Flandreau, Editors (Cambrige: Cambridge University Press)

Borio C (2014) “The International Monetary and Financial System: Its Achilles Heel and What to do About it”, BIS working paper 456, August

Borio C, Enden M, Filardo A, Hofmann B (2015) “The costs of deflation: a historical perspective”, BIS Quarterly Review, March: 31–54

Bussière M, Peltonen T (2008) “Exchange rate pass-through in the global economy - the role of emerging market economies”, European Central Bank working paper 951.

Canay I (2011) A simple approach to quantile regression for panel data. Econ J 14:368–386

Clarida R (2001) The empirics of monetary policy rules in open economies. Int J Financ Econ 6:315–323

Cochrane J (2014) “Monetary Policy with Interest on Reserves” in Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control. Special Issue: Frameworks for Central Banking in the Next Century: A Special Issue on the Occasion of the Centennial of the Founding of the Federal Reserve. (Guest editors: Michael D. Bordo, William Dupour and John B. Taylor)

Collins S, Siklos P (2004) Optimal rules and inflation targeting: are Australia, Canada, and New Zealand different from the US? Open Econ Rev 15:347–362

Cukierman A (1986) “Central Bank Behavior and Credibility: Some Recent Theoretical Developments” Review of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (May): 5–17

Dincer N, Eichengreen B (2007) “Central Bank Transparency: Where, Why, and with What Effects?, NBER working paper 13003, March.

Dincer N, Eichengreen B (2014) Central bank transparency and independence: updates and new measures. Int J Cent Bank 10:189–253

Eijfinger S, Geraats P (2006) How transparent are central bank? Eur J Polit Econ 22:1–21

Engle RF, Rangel J (2005) The spline-GARCH model for low frequency volatility and its macroeconomic causes. Rev Financ Stud 21(3):1187–1222

Goodfriend M (2012) The elusive promise of central banking. Monet Econ Stud 30:39–54

Hashimoto Y, Ito T, Dominguez K (2012) International reserves and the global financial crisis,” with. J Int Econ 88(2):388–406

Im KS, Pesaran MH, Shin Y (2003) Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. J Econ 115:53–74

Kaufmann D, Kraay A, Mastruzzi M (2010) “The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues”, Policy Research working paper 5430, September

Koenker R (2005) Quantile regression. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Mihaljek D, Klau M (2008) “Exchange Rate Pass-Through in Emerging Market Economies: What Has Changed and Why?” In Transmission Mechanisms for Monetary Policy in Emerging Market Economie, pp. 103–30, BIS Papers, no. 35. Basel: Bank for International Settlements.

Reinhart C, Rogoff K (2004) The modern history of exchange rate arrangements: a reinterpretation. Q J Econ 119(1):1–48

Schwert GW (1989) Why does stock market volatility change over time? J Financ 44:1115–1153

Siklos P (2011) Central bank transparency: another look. Appl Econ Lett 18(10):929–933

Siklos P (2013) Sources of disagreement in inflation forecasts: an international empirical investigation. J Int Econ 90:218–231

Siklos PL (2016) Central banks into the breach. Oxford University Press, New York forthcoming

Stock J, Yogo M (2005) Testing for weak instruments in linear IV regression. In: DWK A (ed) Identification and inference for econometric models. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 80–108

Vredin A (2015) “Inflation Targeting and Financial Stability: Providing Policy Makers with Relevant Information”, BIS working paper 503, July

Woodford M (2003) Interest and prices: foundations of a theory of monetary policy. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Part of the research for this paper was done while the second author was a National Fellow at the Hoover Institution and a Visiting Scholar at the University of Tasmania. An appendix to the paper is available on request. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the XVIII Annual Inflation Targeting seminar, Banco Central do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro (May 2016). Comments by José Renato Haas Ornelas are gratefully acknowledged.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bordo, M.D., Siklos, P.L. Central Bank Credibility before and after the Crisis. Open Econ Rev 28, 19–45 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-016-9411-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-016-9411-2

Keywords

- Monetary policy credibility

- Interest rate targeting

- Money growth targeting

- Non-linearity and asymmetry in monetary policy

- Central banking institution