Abstract

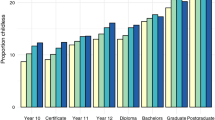

This study examines issues related to the fertility of graduate students over time. First, it examines changes in motherhood rates between 1970 and 2000 among women aged 20–49 who are enrolled in graduate school, both by themselves and relative to prevailing trends among women not enrolled in graduate school, and to other college educated women. Overall, women enrolled in graduate school are increasingly likely to be mothers of young children, and are increasingly similar to non-graduate students. Second, it examines the timing of these births, and finds that almost half of births occur while women are enrolled in graduate school. Third, a brief review of current maternity leave policies and childcare options available to graduate students is presented. Results are discussed in terms of institutional changes within academia, changes between cohorts that attended graduate school in these decades, and the policy needs of graduate student mothers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This measurement does not take into account field of study or type of degree. As shown in Table 1, the enrollment rates of women vary considerably across type of degree. Enrollment rates of women probably also vary considerably across specific fields of study. Unfortunately, information on field of study is not available in any longitudinal study that includes information on graduate student enrollment and fertility rates, and so cannot be taken into account in this study. This measurement also includes both full time and part time enrolled students, as information on whether students were enrolled full time or part time was not collected in the U.S. census. Both female enrollment rates and motherhood rates can vary considerably by field of study and whether enrollment was part time or full time. Part time students may not be enrolled in a degree seeking program, and may be balancing the decision to have a child with both school enrollment and formal employment. The age structure of female graduate students may also vary considerably by field of study, as in some fields of study it is standard practice to work for several years before enrolling in graduate school, and in some fields most students enter graduate school immediately following college. While this should not affect age-standardized examinations of motherhood, this will affect the extent to which findings are relevant to different degree programs, especially if motherhood is concentrated among older students. This paper cannot address these questions due to the discussed data constrains. Future data collection efforts can address the degree to which findings can vary by field of study.

With these data it is impossible to determine the exact extent to which policies affect the fertility of graduate students. Furthermore, between graduate programs, fields of study, and universities, there is considerable variation in motherhood rates, the representation of women, the age structure of graduate students, and family friendly policies. Future research would be able to examine the connection between policy and fertility in greater depth, by examining specific programs and fields of study within schools, the gender and age structure of their programs, their fertility policies and childcare options, and the fertility rates of their female graduate students.

References

Allen, M., & Castlement, T. (2001). Fighting the pipeline fallacy. In A. Brooks & A. Mackinnon (Eds.), Gender and the restructured university. Philadelphia: The Society for Research and Open University Press.

Boulis, A. K., & Jacobs, J. A. (2007). Women becoming doctors: Women’s entry in the medical profession in the United States, 1970–2000. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Conrad, L., & Phillips, E. M. (1995). From isolation to collaboration: A positive change for postgraduate women? Higher Education, 30, 313–322. doi:10.1007/BF01383755.

Cooksey, E. C., & Rindfuss, R. R. (2001). Patterns of work and schooling in young adulthood. Sociological Forum, 16(4), 731–755. doi:10.1023/A:1012842230505.

Dugger, K. (2001). Women in higher education in the United States: 1. Has there been progress? The International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 21(1), 118–130. doi:10.1108/01443330110789637.

Fleer, E. (2004, September, 14). Ditch the boyfriend. The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Garms, I. (2006, April 27). A pregnant pause. The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Gauthier, A. H., & Hatzius, J. (1997). Family benefits and fertility: An econometric analysis. Population Studies, 51(3), 295–306. doi:10.1080/0032472031000150066.

Goldin, C. (2004). The long road to the fast track: Career and family. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 596, 20–35. doi:10.1177/0002716204267959.

Goldin, C., & Katz, L. F. (2002). The power of the pill: Oral contraceptives and women’s career and marriage decisions. The Journal of Political Economy, 110(4), 730–770. doi:10.1086/340778.

Jacobs, J. A. (1996). Gender inequality and higher education. Annual Review of Sociology, 22, 153–185. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.22.1.153.

Jacobs, J. A., & Winslow, S. E. (2004). The academic life course, time pressures, and gender inequality. Community Work & Family, 7(2), 143–161. doi:10.1080/1366880042000245443.

Houseknecht, S. K., & Spanier, G. B. (1980). Marital disruption and higher education among women in the United States. The Sociological Quarterly, 21, 375–389. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.1980.tb00619.x.

Kanter, R. Moss. (1977). Men and woman of the corporation. New York: Basic Books, Inc., Publishers.

Kemkes-Grottenthaler, A. (2003). Postponing or rejecting parenthood? Results of a survey among female academic professional. Journal of Biosocial Science, 35, 213–226. doi:10.1017/S002193200300213X.

Killien, M. (1987). Childbearing choices of professional women. Health Care for Women International, 8(2–3), 121–131.

Mason, M. A., & Goulden, M. (2002). Do babies matter? Academe, 88(6), 21–27.

Mason, M. A., & Goulden, M. (2004a). Marriage and baby blues: Redefining gender equity in the academy. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 596, 86–103. doi:10.1177/0002716204268744.

Mason, M. A., & Goulden, M. (2004b). Do babies matter (Part II)? Closing the baby gap. Academe, 90(6), 10–15.

Mason, M. A., Goulden, M., & Frasch, K. (2007). Graduate student parents: The underserved minority. Communicator. Council of Graduate Schools, 40(4), 1–5.

Miree, C. E., & Frieze, I. H. (1999). Children and careers: A longitudinal study of the impact of young children on critical career outcomes of MBAs. Sex Roles, 41(11/12), 787–808. doi:10.1023/A:1018876211875.

Morgan, S. P. (1996). Characteristic features of modern American fertility. Population and Development Review, 22 (Supplement: Fertility in the United States: New Patterns, New Theories), 19–63.

Preston, S. H., Heuveline, P., & Guillot, M. (2001). Demography: Measuring and modeling population processes. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Rindfuss, R. R., Bumpass, L., & St. John, C., (1980). Education and fertility: Implications for the roles women occupy. American Sociological Review, 45(3), 431–447. doi:10.2307/2095176.

Rindfuss, R. R., Morgan, S. P., & Offutt, K. (1996). Education and the changing age pattern of American fertility: 1963–1989. Demography, 33(3), 277–290. doi:10.2307/2061761.

Rothblum, E. D. (1988). Leaving the ivory tower: Factors contributing to women’s voluntary resignation from academia. Frontiers, 10(2), 14–17. doi:10.2307/3346465.

Ruggles, S., Sobek, M., Alexander, T., Firthc, C. A., Geoken, R., Hall, P. K., et al. (2005). Integrated public use microdata series: Version 3.0 (machine-readable database). Minneapolis, MN: Minnesota Population Center.

Sandefur, G. D., Eggerlilng-Boeck, J., & Park, H. (2005). Chapter 9: Off to a good start? Postsecondary education and early adult life. In R. A. Settersten Jr., F. F. Furstenburg Jr., & R. C. Rumbaut (Eds.), On the frontier of adulthood (pp. 292–392). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Schweber, S. (2005, April 12). It’s all an illusion. The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Smulyan, L. (2004). Redefining self and success: Becoming teachers and doctors. Gender and Education, 16(2), 225–245. doi:10.1080/09540250310001690591.

Spalter-Roth, R., & Kennelly, I. (2004). The best time to have a baby: Institutional resources and family strategies among early career sociologists. ASA Research Brief (pp. 1–18).

Thornton, A., Axinn, W. G., & Teachman, J. D. (1995). The influence of school enrollment and accumulation on cohabitation and marriage in early adulthood. American Sociological Review, 60(5), 767–774. doi:10.2307/2096321.

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2003). Digest of Education Statistics. Tables 267, 270 & 273.

Valian, V. (2004). Beyond gender schemas: Improving the advancement of women in academia. NWSA Journal, 16(1), 207–220. doi:10.2979/NWS.2004.16.1.207.

van Anders, S. M. (2004). Why the academic pipeline leaks: Fewer men than women perceive barriers to becoming professors. Sex Roles, 50(9/10), 511–521. doi:10.1007/s11199-004-5461-9.

Weeks, J. R. (2002). Population: An introduction to concept and issues (8th ed.). Wadsworth Group.

Williams, J. C. (2004a, April 20). Singing the grad-student baby blues. The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Williams, J. C. (2004b, June 17). Easing the grad-student baby blues. The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kuperberg, A. Motherhood and Graduate Education: 1970–2000. Popul Res Policy Rev 28, 473–504 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-008-9108-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-008-9108-3