Abstract

We develop a method for decomposing firm performance to impacts coming from the inflows and outflows of workers and apply it to study whether older workers are costly to firms. Our estimation equations are derived from a variant of the decomposition methods frequently used for measuring micro-level sources of industry productivity growth. By using comprehensive linked employer–employee data, we study the productivity and wage effects, and hence the profitability effects, of the hiring and separation of younger and older workers. The evidence shows that the separations of older workers are profitable to firms, especially in the manufacturing ICT-industries. To account for the correlation of the worker flows and productivity shocks we first estimate the shocks from a production function using materials as a proxy variable. In the second step the estimated shock is used as a control variable in our productivity, wage, and profitability equations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

One dictionary definition of the adjective dysfunctional is “characterized by a breakdown of normal or beneficial relationships between members of the group” (http://www.collinsdictionary.com).

The positive influences of turnover have been emphasized more formally in models where the search and matching process allocates workers to their best uses in firms (e.g. Jovanovic 1979). Worker flows and the matching process may be particularly important for productivity when technological change is rapid (see e.g. Aghion and Howitt 1996).

Vandenberghe (2010) has adopted our decomposition approach.

Often the labor input is disaggregated by using parameters that measure the relative productivities of the worker types (e.g. Hellerstein, Neumark and Troske 1999). In this case, the production function is Y = f(θ 1 L 1 + ··· + θ M L M ) and the productivity terms are \( g_{j} = \left. {\theta_{j} f^{\prime}_{j} } \right|_{{X^{0} }} \).

Our profit variable, the ratio of revenues and costs, is related to profitability measures used in productivity analysis (e.g. Balk 2010; Althin et al. 1996), where it is sometimes called “return to the dollar”. If we consider only value added and assume capital fixed in the short run, our measure is the ratio of net revenue (value added Y) and variable costs. It can also be interpreted as a mark-up. Assume that firms set price equal to unit labor cost multiplied by a mark-up 1 + m, so that we have revenue Y = (1 + m)W(1 + a). The operating margin can be written as OPM = Y − W(1 + a) = (1 + m)W(1 + a) − W(1 + a) = mW(1 + a), and the profit variable equals Π = 1 + m.

The decomposition model is based on the assumption of constant returns to scale, but deviations from constant returns would show up as heteroscedasticity.

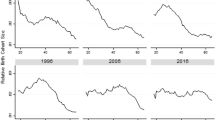

We leave out the period 1990–1994, because our company data are substantially less comprehensive before the year 1995.

These dummies also account for changes in the payroll taxes a, which were assumed fixed in the derivation of the formulas in Sect. 3.

There is some measurement error because temporary agency workers or those with an atypical employment relationship, like service contract, are not included in the employment of the firms. According to the Finnish Private Employment Agencies Association, their employees accounted for only 1 % of total employment in 2010, which is below the European average. This share has been increasing in recent years, but it was still low in the period of our analysis. This kind of employment is more common in services. This is one reason why we estimate the models also by sector (industry and services). In principle, owner-managers can also cause measurement error. For small firms where the owner is working, he is included in the number of employees only if he takes at least half of his income as salary (as opposed to capital income). In any case, the restrictions we use (i.e., leaving out firms with less than ten employees and firms with missing employer-firm link) mean that this measurement error should not be large. We thank an anonymous referee for pointing out these issues to us.

The proxy variable approach is based on the assumption that capital is inherited from the previous period, and the proxy variable (materials) and labor choices happen after the shock is realized. Therefore, the latter variables are endogenous, but capital stock itself is not.

Some of the firms operate in more than one region. The region of a firm refers to the one where the employment share is the highest.

The number of observations drops because of the reasons discussed in the text.

Note that these figures underestimate actual turnover among the employees, since e.g. hiring of an employee after the start of a period and subsequent separation of the same employee before the end of the period is not included in the turnover rates.

There are two main reasons why we prefer using employment weighted estimation. Firstly, we are ultimately concerned of productivity differences between different employment groups. Unfortunately we are unable to measure productivity at the level individuals but only at the level of firms so that in a sense we are using aggregated data. In order to give an equal weight for each individual in our analysis, we should give a larger weight to large firms than to smaller firms. Second, weighted estimation provides us with a more efficient procedure in the presence of heteroscedasticity.

In the Finnish pension system the pension was until 1996 based on the last four years’ pay and until 2004 on the last ten year’s pay in each employment relationship, which gave incentives for obtaining a high pay at the end of the career. This combination of backloaded wage and a fixed retirement age is consistent with the deferred payment model of Lazear (1979), although it is a result of a quite different institutional setting. The system has been based on a mix of centralized negotiations between labor unions, employer organizations and the government, and firm-level wage setting. Lazear’s argument is somewhat difficult to use in the connection of labor flows, as it is an equilibrium model where the raising wage profile and unprofitability of the older employees is part of the “package”. However, even in this case unexpected increases in the costs of older employees or an increase in the share of older employees through aging may make the system unsustainable and give raise to incentives for separations.

The probability of exit was modelled as a function of firm size, industry, employee characteristics (average tenure and education years, share of women), capital-labor ratio, productivity shock, and an indicator for growing firms. All of these variables were measured in the year prior to exit.

In addition to the unemployment pension system, also disability pension gives incentives for laying off older employees. The larger firms are responsible for paying (part of) the disability pension until the normal retirement age. This can be avoided, if the worker goes to the unemployment pension tunnel before possible disability.

See discussion in Daveri (2004). The results obtained by using the broad definition of ICT are available on request. It should be noted that “Financial intermediation” (ISIC 65–67) industries are excluded from our estimation sample.

Also the econometric framework could be extended. We have used the proxy variable approach indirectly by estimating the shock from a level form and then using it in our difference form model. It remains an open issue how the approach could be directly applied to our model in one step. Also extensions to for example stochastic frontier models would be interesting.

References

Abowd JM, Kramarz F (1999) The analysis of labor markets using matched employer–employee data. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds) Handbook of labor economics, vol 3b. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 2629–2710

Ackerberg D, Benkard CL, Berry S, Pakes A (2007) Econometric tools for analyzing market outcomes. In: Heckman JJ, Leamer EE (eds) Handbook of econometrics, vol 6. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 4171–4276

Aghion P, Howitt P (1996) The observational implications of Schumpeterian growth theory. Empir Econ 21:13–25

Althin R, Färe R, Grosskopf S (1996) Profitability and productivity changes: an application to Swedish pharmacies. Ann Oper Res 66:219–230

Aubert P, Crépon B (2003) La productivité des salariés âgés: une tentative d’estimation. Écon Stat 368:95–119

Aubert P, Caroli E, Roger M (2006) New technologies, organisations and age: firm-level evidence. Econ J 116:73–93

Balk BM (2010) Measuring productivity change without neoclassical assumptions: a conceptual analysis. In: Diewert WE, Balk BM, Fixler D, Fox KJ, Nakamura A (eds) Price and productivity measurement, vol 6., Index Number TheoryTrafford Press, Victoria, pp 133–154

Balk BM (2016) The dynamics of productivity change: a review of the bottom-up approach. In: Greene WH, Khalaf LC, Sickles, R, Veall M, Voia MC (eds) Productivity and Efficiency Analysis, Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics, pp 15–49

Balsvik R (2011) Is labor mobility a channel for spillovers from multinationals? Evidence from Norwegian manufacturing. Rev Econ Stat 93:285–297

Bingley P, Westergaard-Nielsen N (2004) Personnel policy and profit. J Bus Res 57:557–563

Boschma R, Eriksson R, Lindgren U (2009) How does labour mobility affect the performance of plants? The importance of relatedness and geographical proximity. J Econ Geogr 9:169–190

Cataldi A, Kampelmann S, Rycx F (2011) Productivity-wage gaps among age groups: does the ICT environment matter? De Economist 159:193–221

Dalton DR, Todor WD, Krackhardt DM (1982) Turnover overstated: the functional taxonomy. Acad Manag Rev 7:117–123

Daniel K, Heywood JS (2007) The determinants of hiring older workers: UK evidence. Labour Econ 14:35–51

Daveri F (2004) Delayed IT usage: is it really the drag on Europe’s productivity. CESifo Econ Stud 50:397–421

Daveri F, Maliranta M (2007) Age, seniority and labour costs: lessons from Finnish IT revolution. Econ Policy 22:117–175

Diewert WE, Fox KA (2009) On measuring the contribution of entering and exiting firms to aggregate productivity growth. In: Diewert WE, Balk BM, Fixler D, Fox KJ, Nakamura A (eds) Price and productivity measurement, vol 6., Index number theoryTrafford Press, Victoria, pp 41–66

Foster L, Haltiwanger J, Krizan CJ (2001) Aggregate productivity growth: lessons from microeconomic evidence. In: Hulten CR, Dean ER, Harper MJ (eds) New developments in productivity analysis. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 303–363

Foster L, Haltiwanger J, Syverson C (2008) Reallocation, firm turnover, and efficiency: selection on productivity or profitability? Am Econ Rev 98:394–425

Göbel C, Zwick T (2012) Age and productivity: sector differences. De Economist 160:35–57

Göbel C, Zwick T (2013) Are personnel measures effective in increasing productivity of old workers? Labour Econ 22:80–93

Griliches Z, Mairesse J (1998) Production functions: the search for identification. In: Strøm R (ed) Econometrics and economic theory in the twentieth century: the Ragnar Frisch Centennial symposium. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 169–203

Hadi AS (1992) Identifying multiple outliers in multivariate data. J R Stat Soc B 54:761–771

Hadi AS (1994) A modification of a method for the detection of outliers in multivariate samples. J R Stat Soc B 56:393–396

Hakola T, Uusitalo R (2005) Not so voluntary retirement decisions? Evidence from a pension reform. J Public Econ 89:2121–2136

Haltiwanger J (1997) Measuring and analyzing aggregate fluctuations: the importance of building from microeconomic evidence. Fed Reserve Bank St. Louis Econ Rev 79:55–77

Haltiwanger JC, Lane JI, Spletzer JR (1999) Productivity differences across employers: the roles of employer size, age, and human capital. Am Econ Rev 89:94–98

Haltiwanger JC, Lane JI, Spletzer JR (2007) Wages, productivity, and the dynamic interaction of businesses and workers. Labour Econ 14:575–602

Hellerstein JK, Neumark D (2007) Production function and wage equation estimation with heterogeneous labor: Evidence from a new matched employer–employee data set. In: Berndt ER, Hulten CM (eds) Hard to measure goods and services: essays in honor of Zvi Griliches. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 31–71

Hellerstein JK, Neumark D, Troske KR (1999) Wages, productivity, and worker characteristics: evidence from plant-level production functions and wage equations. J Labor Econ 17:409–446

Hutchens R (1986) Delayed payment contracts and a firm’s propensity to hire older workers. J Labor Econ 4:439–457

Hutchens R (1988) Do job opportunities decline with age? Ind Labor Relat Rev 42:89–99

Ilmakunnas P, Ilmakunnas S (2015) Hiring older employees: do the age limits of early retirement and the contribution rates of firms matter? Scand J Econ 117:164–194

Ilmakunnas P, Maliranta M (2005) Technology, labour characteristics and wage-productivity gaps. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 67:623–644

Ilmakunnas P, Maliranta M, Vainiomäki J (2004) The roles of employer and employee characteristics for plant productivity. J Prod Anal 21:249–276

Ilmakunnas P, Maliranta M, Vainiomäki J (2005) Worker turnover and productivity growth. Appl Econ Lett 12:395–398

Ilmakunnas P, van Ours J, Skirbekk V, Weiss M (2010) Age and productivity. In: Garibaldi P, Martins JO, van Ours J (eds) Ageing, health, and productivity: the economics of increased life expectancy. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 133–240

Jovanovic B (1979) Job matching and the theory of turnover. J Polit Econ 87:972–990

Kaiser U, Kongsted HC, Rønde T (2015) Does the mobility of R&D labor increase innovation? J Econ Behav Organ 110:91–105

Kronenberg K, Carree M (2010) The effects of workforce composition, labor turnover, and the qualities of entering and exiting workers on productivity growth. Maastrict University, Mimeo

Kyyrä T, Wilke RA (2007) Reduction in the long-term unemployment of the elderly: a success story from Finland. J Eur Econ Assoc 5:154–182

Lazear EP (1979) Why is there mandatory retirement? J Polit Econ 87:1261–1284

Levinsohn J, Petrin A (2003) Estimating production functions using inputs to control for unobservables. Rev Econ Stud 70:317–341

Mahlberg B, Freund I, Crespo Cuaresma J, Prskawetz A (2013a) Ageing, productivity and wages in Austria. Labour Econ 22:5–15

Mahlberg B, Freund I, Crespo Cuaresma J, Prskawetz A (2013b) The age-productivity pattern: do location and sector affiliation matter? J Econ Ageing 1–2:72–82

Maliranta M (1997) Plant-level explanations for the catch-up process in Finnish manufacturing: A decomposition of aggregate labour productivity growth. In: Laaksonen S (ed) The evolution of firms and industries. International perspectives. Stat Finl, Helsinki, pp 352–369

Maliranta M, Ilmakunnas P (2005) Decomposing productivity and wage effects of intra-establishment labor restructuring. ETLA Discussion Papers No. 993, Helsinki

Maliranta M, Mohnen P, Rouvinen P (2009) Is inter-firm labor mobility a channel of knowledge spillovers? Evidence form a linked employer–employee panel. Ind Corp Change 18:1161–1191

Munnell AH, Sass SA (2008) Working longer. The solution to the retirement income challenge. Brookings Institution Press, Washington

Nelson RR, Phelps ES (1966) Investment in humans, technological diffusion, and economic growth. Am Econ Rev Pap Proc 56:69–75

Olley GS, Pakes A (1996) The dynamics of productivity in the telecommunications equipment industry. Econometrica 64:1263–1297

Parrotta P, Pozzoli D (2012) The effect of learning by hiring on productivity. RAND J Econ 43:167–185

Siebert WS, Zubanov N (2009) Searching for the optimal level of employee turnover: a study of a large U.K. retail organization. Acad Manag J 52:294–313

Skirbekk V (2008) Age and productivity potential: a new approach based on ability levels and industry-wide task demand. Pop Dev Rev 34(Supplement):191–207

Stoyanov A, Zubanov N (2012) Productivity spillovers across firms through worker mobility. Am Econ J Appl Econ 4:168–198

Towers Perrin (2005) The business case for workers age 50+. AARP, Washington

Vainiomäki J (1999) Technology and skill upgrading: results from linked worker-plant data for Finnish manufacturing. In: Haltiwanger J, Lane J, Spletzer JR, Theuwes JM, Troske KR (eds) The creation and analysis of employer–employee matched data. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 115–145

van Ark B, Inklaar R, McGuckin R (2003) ICT and productivity in Europe and the United States. Where do the differences come from? CESifo Econ Stud 49:295–318

van Dalen HP, Henkens K, Schippers J (2010) Productivity of older workers: perceptions of employers and employees. Popul Dev Rev 36:309–330

van Ours JC, Stoeldraijer L (2011) Age, wage and productivity in Dutch manufacturing. De Economist 159:113–137

Vandenberghe V (2010) Shed the oldies … it’s profitable. Universite Catholique de Louvain, Mimeo

Vandenberghe V (2013) Are firms willing to employ a greying and feminizing workforce? Labour Econ 22:30–46

Vandenberghe V, Waltenberg F, Rigo M (2013) Ageing and employability. Evidence from Belgian firm-level data. J Prod Anal 40:111–136

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to many individuals at Statistics Finland, and especially to Satu Nurmi and Elias Einiö for their guidance regarding the properties of the data. The data set is publicly available for research purposes, subject to terms and conditions of confidentiality, at the Research Services unit of Statistics Finland; contact tutkijapalvelut@stat.fi, for access to these data. We have benefited from the comments of Roope Uusitalo and seminar participants at the VATT Institute for Economic Research (Helsinki), Nordic Summer Institute in Labor Economics in Uppsala, EEA Congress in Vienna, CAED Conference in Chicago, Annual Meeting of the Finnish Society for Economic Research in Helsinki, World Aging and Generations Congress in StGallen, and Workshop on Labor Turnover and Firm Performance, Helsinki. We thank the referees and associate editor for useful comments. Financial support from the Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation is gratefully acknowledged. The SAS and Stata codes used in this study are available from the authors upon request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ilmakunnas, P., Maliranta, M. How does the age structure of worker flows affect firm performance?. J Prod Anal 46, 43–62 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11123-016-0471-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11123-016-0471-5