Abstract

In June 2001, the Chinese Government announced proposals to reduce its retained ownership in listed Chinese state-owned enterprises. In the 3 months following the announcement, the market fell by 40 % and as a consequence, in 2002 the programme was cancelled. The Government learnt lessons and in April 2005 it launched a revised plan to sell its shares, known as the Full Circulation Reform. The new reform was carefully guided by official document releases, trialled with a pilot programme, and then extended to the majority of firms in groups over a 2-year period. The process was known as a gradual, offer-to-get approach. At the firm-level, each reforming company gradually implemented the sale of its Government-held shares through one negotiation stage and one voting stage. Part of the negotiation stage centred on the compensation that would be paid by the Government to the public shareholders to ensure that the reforms went through. This paper investigates market reactions around the critical event dates in the reform process and the underlying dynamics. The results show that this reform had positive impact on prices, indicating the gradual and offer-to-get approach was very successful and Government objectives for the sale were met.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China, the average Government ownership of listed firms peaked in 1993 (75.6 %) but reduced to 63.9 % in 2004.

The term Consideration appeared in Measures (2005) in Article 16 in order to “implement the compensation plan specifically designed to balance the interests of each party in the Split Share Structure Reform” but was not specified in terms of the exact definition and meaning.

Details are provided in Sect. 3.

China SOE Reform is a centerpiece of the overall Chinese overall reform of transforming from a centrally planned economic system to a market-oriented system (Liu and Gao 1999). From 1949 to 1979, the Government controlled all major sectors of the economy and formulated all decisions about the use of resources and the distribution of output. Planners decided what should be produced in accordance with national and social objectives. SOE executives were appointed and dismissed by the Government and usually treated as Government officials (Liu and Gao 1999). Since the 3rd Plenum in 1978, Chinese SOEs have been gradually given more and more autonomy to take control themselves, dealing with relevant rights and responsibilities. However, SOE executives were not fully responsible for any losses in their companies. This situation aggravated the moral hazard problem and led to increasing losses reports in many China SOEs. The policy of Zhuada fangxiao (grasping the large and letting go of the small) in the early 1990s had successfully privatised the failing and smaller SOEs through restructuring, selling and mergers, while some relatively strong medium and large-sized SOEs were selected to be transformed into publicly listed firms on the Chinese stock market. The Government didn’t sell all of the shares in the SOEs at once. They cautiously retained a substantial ownership in the listed SOEs. In general, two-thirds of Chinese domestic shares were held by the central Government through state asset management agencies or by their SOE representatives. Only about one third were issued to public investors.

A further split in the structure arose through the denomination of A shares that were available uniquely to Chinese investors, and B shares that were available uniquely to foreign investors (Guo et al. 2013). Government shares were categorised therefore as non-tradable A shares (NTAS). Tradable shares could be further divided into tradable A shares (TAS) and tradable B shares (TBS). This paper is concerned only with the A-share market and A-share owners as the B-share market and owners weren’t affected by the sale of Government shares.

For instance, the UK retained controlling ownership in some of the SOEs at the first sale in 1980s, when decentralization sparked and swept around the UK, an extreme example market-oriented privatization in JMNN (1999).

Such as obtaining soft loans from listed firms; using listed firms as guarantors to borrow money from banks, and buying and selling goods, services and assets at unfair prices.

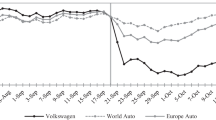

Data calculated from DataStream.

Since the very start of economic reforms in China in 1978, the Chinese Government has played an important role. Many economists argued that China's success demonstrated the superiority of an evolutionary, experimental, bottom-up approach over the comprehensive and top-down "shock therapy" approach that characterized the transition in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union (McKinnon 1994; Jefferson and Rawski 1995). However, the 40 % fall in the markets in 3 months after the announcement of Measures (2001) indicated that it was apparent that the announcement of privatisation at this time shocked the stock markets and the investors.

Chinese reforms are deemed successful in many studies including Tsai and Wu (1999).

Cumulative voting is a type of voting process that helps strengthen the ability of minority shareholders to elect a director. This method allows shareholders to cast all of their votes for a single nominee for the board of directors when the company has multiple openings on its board. In contrast, in "regular" or "statutory" voting, shareholders may not give more than one vote per share to any single nominee.

The separation of equity ownership refers to the separation between the tradable and non-tradable shares. Tradable shares have trading rights while non-tradable shares don’t. It also stated that “When resolving this issue, the solution must respect market laws, contribute to the stability and development of the market and genuinely protect the lawful rights and interests of investors, in particular public investors.”

However, more work needs to be done to promote the understanding of on-line voting among investors and increase the turnout rate (statistics show that those who have voted on-line represent no more than 10 % of the tradable shares of the company).

China adopted a gradual, evolutional approach to the transition from a planned economy to a market economy since its overall reform started at the end of 1978. This approach has often been said to “piecemeal, partial, incremental, often experimental, especially without large-scale privatisation” (Lin 2004). The gradual approach was also applied in the SSSR.

It is not uncommon for the Government to pay a premium to the public investors in order to secure their proposals. When privatizing SOEs by selling the ownership on the stock markets, governments across the world usually underpriced shares of SOEs more than in private equity offerings (Jenkinson and Mayer 1988; Jelic and Briston 1999; Choi and Nam, 1998; Ljungqvist and Wilhelm 2003).

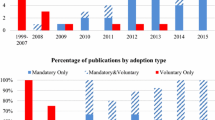

There were 1,345 SOEs involved. The reform process took place in orderly groups. In total, there were 66 groups.

The holders of TAS are public investors who own the tradable shares, including domestic and foreign institutional investors as well as Chinese individuals. Foreign investors were forbidden to purchase Yuan-denominated "A" shares before 2002. But the QFII (Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors) program launched in 2002 allowed licensed foreign investors to buy and sell "A" shares. The holders of NTAS are the government owners of non-tradable shares. The holders of TAS and NTAS were on opposite sides of the negotiating table bargaining for a better deal for their own groups during the first suspension period. But the two groups had different objectives. According to Firth et al. (2010), the government had strong incentives to complete the reform smoothly and quickly while institutional investors, mainly mutual funds, were keen to bargain for better terms in the reform package, and individual shareholders were likely to be free-riders (Davis and Kim 2007). In some ways, the situation is similar to a union/management negotiation. One group, traditionally considered weak in bargaining power relative to the other group, takes certain actions against the “strong group” who then has to face the “weak group” squarely at the negotiating table. In 2001, the relatively weak TAS holders dumped their shares, resulting in a disastrous and persistent market slump when the relatively strong Government attempted to sell 10 % of their shares. In a similar vein, a union may organize a strike amongst relatively weak employees to coerce the relatively strong managers to negotiate over the terms proposed by them. In the SSSR negotiation, the Government NTAS in each firm brought the reform proposal to the table (see Figure 3) to discuss and negotiate with the TAS holders, indicating that the Government is eager and anxious to get a deal from the TAS holders rather than the other way around. The Government spent almost three years setting up a regulation system to “flatter” the TAS owners because the Government is “bold” and “determined” (Kazakevitcha and Smyth 2005) to complete the sale of shares. In a negotiation, it is more likely the pursued has more bargaining power than the pursuer as it is easier for the pursued to leave the table, Particularly the TAS holders have been given the voting right to say “No” if they didn’t like the deal. The evidence is 72 % of the sample companies (430 out of 599) revised their compensation ratios upwards by 4.7 % after the negotiation.

The full Chinese text is available on request.

It decentralized decision-making at the firm level, by allowing shareholders to bargain over the method and terms of the compensation. Furthermore, it safeguarded the interests of TAS holders by seeking no less than two-thirds of the votes from the TAS owners, compensating them for the estimated loss due to the reform, diluted the risks by introducing a series of announcements dates, prevented market slump by banning any sale of NTAS in the twelve months following the reform and restricted any issue size in the following 24 months.

Please see Appendix 1 for the Group summary.

The reform was not fully completed by the end of 2006 as the Government intended. There were 40 “difficult” firms that did not successfully reform.

(1) Pre-suspension: A reform proposal should be submitted to the board of directors by a shareholder/shareholders holding individually/collectively two-thirds of the NTAS of the listed company. The board must seek the cooperation of an external underwriting institution and of a law firm to formulate the proposal. (2) 1st suspension: Once authorized by the CSRC, the firm information, together with the other firms authorized simultaneously, would be announced as a group (Group Announcement). The firm should suspend immediately, usually one day after the Group Announcement, publicize the initial reform proposal, including date of the shareholders’ meeting, a description of the reform proposal as well as the opinions of the recommending institution and the law firm. (3) 1st resumption: Within 10 days after the 1st suspension, the board should assist the owners of NTAS in adequately communicating and negotiating with the holders of TAS. Approaches include for example hosting an investor symposium, a press conference or an online road show, paying a visit to institutional investors and issuing a consultation paper. In addition, the board of directors of the listed company should publicly disclose its hotline, facsimile and e-mail address in order to widely solicit opinions from tradable shareholders so as to lay a broad shareholder foundation for the reform plan. If the proposal was acceptable to both parties, an announcement of consensus would be made and trading should resume. (4) 2nd suspension: The firm should suspend one day before the scheduled registration date of the shareholders’ meeting. (5) 2nd resumption : Once the proposal won two thirds of votes from the NTAS holders and from the TAS holders, the firm should publicize the proposal and the “pass” result within two days, at the same time apply to resume trading. Once resumed, the reform was successfully implemented and the compensation would be paid. If the proposal was rejected, the firm had to publicize a “fail” result within two days and apply to resume trading. (6) A 12 month lockup period was established for the holders of NTAS. The initial 12-month lockup expired on t12. Furthermore, in the two years after expiration of the lock-up, holders of NTAS with more than 5 % of the total issued share capital of the listed company were further prohibited from trading on the stock exchange more than 5 % (10 %) of the company’s total share capital within 12 (24) months.

The term Consideration appeared in Measures (2005) in Article 16 in order to “implement the compensation plan specifically designed to balance the interests of each party in the Split Share Structure Reform” but was not specified in terms of the exact definition and meaning.

Please see Appendix 2.1 for details.

Appendix 2.1 gives details on the major approaches used by firms to calculate Consideration ratios.

Some of these firm-specific variables are in line with what are suggested in Rahman and Hassan (2013).

For example, in Figure 1, Guidelines (2005) was announced on 8th May, the first working day after Notice (2005) was launched on 29th April, as there were eight public holidays in between, and the announcement of the first pilot group was one day immediately after Guidelines (2005). In addition, the sample companies staged reform in 66 groups spanning from 9th May 2005 to 31st Dec 2006. Firms arranged in the same groups started reform around the same time. The time interval between groups is 5 trading days. In the sample, on average 45 trading days were taken to complete an individual reform process, sufficiently long to allow another nine groups to announce reforms. Previous studies have documented intra-industry information transfer between announcing and non-announcing firms in various settings such as earnings announcements (Foster 1981, Freeman and Tse 1992), dividend change announcement (Firth 1996), security offerings (Szewczyck 1992) and stock split announcement (Tawatnuntachai and D’Mello 2002). Prior research has also suggested that large firms’ reactions to common information lead those of small firms (Lo and MacKinlay 1990; Brennan et al. 1993; Asthanta and Mishra 2001), especially in assessing the stock prices of non-announcing firms in the business affiliate (Huang and Chang 2009), such as cross-shareholding of listed firms, which is a very common practice among China listed firms (Guo and Yakura 2009). In the scenario of China’s SSSR, those results suggest that firms which made earlier reform announcements could convey information about key elements in the reform proposal and process to those non-announcing firms within the same industry, or of smaller sizes, or closely connected, synchronously affecting their security prices at that time. As a consequence, there is scope for confounding events.

The first pilot group announcement is included for investigation, thus the event date of Guidelines (2005) is excluded for redundancy.

Empirical studies find significant negative market reactions around the IPO lockups (Field and Hanka 2001; Bradley et al. 2001) and argue that the decline around the expiration day is partly due to price pressure and partly to worse-than-expected news about insider sales. These findings support the idea that the price movements around the IPO lockup are not relevant to the “lockup expiration” which was stated in the initial IPO prospectus, but due to the additional new information around the expiration day. Limited research has been conducted concerning the t12m and t24m dates, for example Liao et al. (2011), who examined an event period of [−120, +20] days around the lock-up expirations. They noted that a large portion of the decrease in average CAR they found took place between day −120 and day −40 (and not at the lock-up expiration dates), with the CAR curve becoming flat after the lock-ups expire. They also documented that only around 4 % of the firms chose to sell NTAS with 91 days after lockup. They suggested that negative returns are not likely to be caused by the post lock-up sales of NTAS.

Please see Footnote 27 for details. An average interval between two consecutive groups is 5 working days, indicating an event window of (−5, +5) would involve confounding effects from two other group events. This is particularly the case since firms took an average of two months to complete the reform procedure. Therefore the outcomes of firms from a group within these two months could impact on other firms in the group.

For example, the day after the Notice (2005) release was Saturday, 30th April 2005, followed by a seven-day Public holiday called Labours’ Day from 1st May till 7th May. 8th May 2005 was a Sunday. Therefore the first trading day after Notice (2005) issuance was 9th May 2005, which overlapped the announcement of the first pilot group. Consequently the event window for Notice (2005) is (−1, 0).

These firms tried at least twice or even three times to enter the reform process but they still failed. Therefore they are considered extreme examples.

Sina Finance records the process and operation of China Split-share Structure reform at firm-level, including reform proposal, critical dates and other details in implementation. Datastream provides trading and market data. Resset Database is China’s leading provider of financial databases and software solutions for financial and investment research, where firm characteristics information is constructed in a standardized format.

Because data processing in an event-study requires at least two years of consistent data prior to China SSSR. The two years are essential to estimate the normal returns without the reform, which is discussed in detail later.

A back-door listing company is seeking listing on exchanges by acquiring an already listed company. A back-door listed company may alter the core business of the previous one and thus lead to a discontinuity and inconsistency in firm data.

Back-listing replaces a listed firm with a new entry. The data of the replaced firm has little connection with that of the replacing firm other than the listing code. In other words, a firm newly back-door listed is no different from a firm newly-listed except that the former inherits an already-existent listing code while the later is allocated a new code. Therefore a back-door listing history within two years indicates no consistent data is available.

In the literature, ARs have been measured as (1) mean-adjusted returns (2) market-adjusted returns, (3) OLS market mode: deviations (prediction errors) from the market model, (4) deviations from the one factor Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) or (5) deviations from a multifactor model, such as the Arbitrage Pricing Theory (APT).

Parameters are estimated using an estimation period sample with OLS regression. The parameter estimates and the event period stock and market index returns are then used to estimate the ARs.

For example, the estimation period is from day −245 till day −6 relative to the event day (Brown and Warner 1980, 1985), the year ending 50 days before the event (Fama and French 1996), from day −250 till day −21 prior to the event (MacKinlay 1997), from day −250 to day −51 (Pojezny 2006), from day −250 to day −30 (2007), from day −244 to day −6 (Ahern 2009), from day −200 to day −3 (Huang and Chang 2009) etc.

Roenfeldt et al. (1978) investigated the effect varying the length of the second sub-period on the stability of individual security betas and found 4-year period estimation period was most reliable. Theobald (1981) showed that beta stationarity increased with the calendar period length but did not increase indefinitely. He suggested an optimal estimation period of 180–210 months for UK monthly data. Daves et al. (2000) concluded that a much shorter estimation period of 2–3 years was more appropriate for financial managers to use when estimating beta with daily returns. Diacogiannis and Marki (2008) showed that the utilization of an estimation period of three years captured most of the maximum reduction in the standard error of beta estimated as compared to other periods with Athens stocks.

They found that the mean of beta was the closest to 1 for an estimation period from 1.5 to 2 years starting from 1.5 years after the interested event. The smallest standard deviation came with an estimation window of 2 years starting from 6 weeks after the event of interest.

Statistical tests can be performed to adjust for cross-sectional and time-series dependence. Please see Section 4.

Agency problem here refers to the conflicts between the majority shareholders and the minority shareholders and therefore is proxied by the ratio of non-tradable shares to tradable shares.

The approaches include hosting an investor symposium, a press conference or an online road show, paying a visit to institutional investors and issuing a consultation paper. In addition, the board of directors of the listed company should publicly disclose its hotline, facsimile and e-mail address in order to widely solicit opinions from tradable shareholders so as to lay a broad shareholder foundation for the reform plan.

Only selected results are shown and analysed in this article. Please see Appendix 4 for the full regression results.

Please refer to Table 1.

Please refer to Appendix 3 for more details.

Appendix 3 explains the three tests in detail.

Companies were suspended from the start day of the individual reform and there was no trading for a while, indicating there was no price available on that day (event day) and the subsequent day. They didn’t explain how they managed to calculate the 2- and 3-day CARs around the individual company’s announcement to commence the reform, in the absence of data. Second their event window and estimation window overlapped on day −1 relative to the event day. This may affect the estimation of parameters and calculation of t statistics, leading to biases in results.

(1) Firms in the same group may have great chance to share the same 1st resumption day; (2) The five-working-day group interval may increase the chance for firms in different groups to have the same 1st resumption day. For instance, 599 sample companies have 207 1st resumption dates. On average, approximately every three sample companies share the same 1st resumption dates.

Appendix 5 lists formulas to adjust Consideration ratios in different styles to equivalent bonus shares.

Lu et al. (2008) included 3 sample companies which paid Consideration in cash, 1 sample company which used warrant type and 22 sample companies which selected combination type, which indicates their results from Consideration type dummies are not very convincing.

This number is in Appendices 4.4 and 4.5.

The formula to compute the estimated return assuming a drop by Consideration: \(E(R_{i0} ) = {1 \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 {(1 + Con_{i} )}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {(1 + Con_{i} )}} - 1\);

The formula to compute the estimated AR: \(E(AR_{i0} ) = E(R_{i0} ) - \alpha_{i} - \beta_{i} R_{m0}\).

References

Ahern KR (2009) Sample selection and event study estimation. J Empir Financ 16(3):466–482

Aktas N, De Bodt E, Cousin JG (2007) Event studies with a contaminated estimation period. J Corp Financ 13(1):129–145

Asthanta SC, Mishra BK (2001) The differential information hypothesis, firm size, and earnings information transfer: an empirical investigation. J Bus Res 53(1):37–47

Baesel J (1974) On the assessment of risk: some further compensations. J Financ 29(5):1491–1494

Bai CE, Liu QJ, Lua J, Song FM, Zhang JX (2004) Corporate governance and market valuation in China. J Comp Econ 32(4):599–616

Beaver WH (1968) The information content of annual earnings announcements. J Acc Res 6(Supplement):67–92

Beltratti A, Bortololli B (2006) The nontradable share reform in the Chinese stock market. Working paper, Bocconi University and Torino University

Binder JJ (1998) The event study methodology since 1969. Rev Quant Financ Account 11(2):111–137

Bradley D, Jordan B, Yi H, Roten I (2001) Venture capital and IPO lockup expiration: an empirical analysis. J Financ Res 24(4):465–493

Brau J, Lambson V, McQueen G (2005) Lockups revisited. J Financ Quant Anal 40(3):519–530

Brav A, Gompers P (2003) The role of lockups in initial public offerings. Rev Financ Stud 16(1):1–29

Brennan MJ, Jegadeesh N, Swaminathan B (1993) Investment analysis and the adjustment of stock prices to common information. Rev Financ Stud 6(4):799–824

Brockman P, Chung DY (2008) Investor protection, adverse selection, and the probability of informed trading. Rev Quant Financ Account 30(2):111–131

Brown S, Warner J (1980) Measuring security price performance. J Financ Econ 8(3):205–258

Brown S, Warner J (1985) Using daily stock returns: the case of event studies. J Financ Econ 14(1):3–31

Calomiris CW, Fisman R, Wang YX (2010) Profiting from Government stakes in a command economy: evidence from Chinese asset sales. J Financ Econ 96(3):399–412

Campbell CJ, Wasley CE (1993) Measuring security price performance using daily NASDAQ returns. J Financ Econ 33(1):73–92

Chen GM, Firth M, Kim JB (2000) The post-issue market performance of initial public offerings in China’s new stock markets. Rev Quant Financ Account 14(4):319–339

Chi J, Padgett C (2005) The performance and long-run characteristics of the Chinese IPO market. Pac Econ Rev 10(4):451–469

Choi S, Nam S (1998) The short run performance of IPOs of privately and publicly owned firms: international evidence. Multinatl Financ J 2(3):225–244

Corrado C (1989) A nonparametric test for abnormal security-price performance in event studies. J Financ Econ 23(2):385–395

Cowan AR (1992) Nonparametric event study tests. Rev Quant Financ Account 2(4):343–358

Daves PR, Ehrhardt MC, Kunkel RA (2000) Estimating systematic risk: the choice of return interval and estimation period. J Financ Strateg Decis 13(1):7–13

Davis GF, Kim EH (2007) Business ties and proxy voting by mutual funds. J Financ Econ 85(2):552–570

De Jonge A (2008) Corporate governance and China’s H-share market. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Diacogiannis G, Marki P (2008) Estimating betas in thinner markets: the case of the Athens stock. Int Res J Financ Econ 13:108–122

Errunza V, Miller D (2003) Valuation effects of seasoned global equity offerings. J Bank Financ 27(9):1611–1623

Fama EF, French KR (1996) Multifactor explanations of asset pricing anomalies. J Financ 51(1):55–84

Fama EF, Fisher L, Jensen MC, Roll R (1969) The adjustment of stock prices to new information. Int Econ Rev 10(1):1–21

Field L, Hanka G (2001) The expiration of IPO share lockups. J Financ 56(2):471–500

Firth M (1996) Dividend changes ARs intra-industry firm valuations. J Financ Quant Anal 31(2):189–212

Firth M, Lin C, Zou H (2010) Friend or foe? The role of state and mutual fund ownership in the split share structure reform in China. J Financ Quant Anal 45(3):685–706

Foster G (1981) Intra-industry information transfers associated with earnings releases. J Account Econ 3(3):201–232

Freeman RN, Tse S (1992) An earnings prediction approach to examining intercompany information transfer. J Account Econ 15(4):509–523

Green SP (2003) China’s stock markets: eight myths and some reasons to be optimistic. Working Paper No. 6, Standard Chartered Bank (Hong Kong) Limited China Project

Green S, Liu GS (2005) China’s industrial reform strategy: retreat and retain. In: Liu GS, Sun P (eds) China’s public firms: How much privatization?. Blackwell, London, pp 15–41

Guo EY, Keown AJ (2009) Privatization and non-tradable stock reform in China: the case of Valin Steel Tube & Wire Co., Ltd. Glob Financ J 20(2):191–208

Guo L, Yakura S (2009) The cross holding of company shares—a preliminary legal study of Japan and China. Front Law China 4(4):507–522

Guo L, Tang L, Yang SX (2013) Corporate governance and market segmentation: evidence from the price difference between Chinese A and H shares. Rev Quant Financ Account 41(2):385–416

Hou WX (2012) The valuation of restricted shares by conflicting shareholders in the split share structure reform. Eur J Financ. doi:10.1080/1351847X.2012.671782

Huang C, Chang C (2009) Information transfer among group-affiliated firms. Contemp Manag Res 5(1):3–14

Huang Q, Levich RM (2003) Underpricing of new equity offerings by privatised firms: an international test. Int J Theor Appl Financ 6:1–30

Jefferson G, Rawski T (1995) How industrial reform worked in China: the role of innovation competition property rights. Working paper. In: Proceedings of the World Bank annual conference on development economics 1994, The World Bank, Washington, DC, pp 129–156

Jelic R, Briston R (1999) Hungarian privatisation strategy and financial performance of privatised companies. J Bus Financ Account 26(9–10):1359–1368

Jenkinson T, Mayer C (1988) The privatisation process in France and UK. Eur Econ Rev 32(2–3):482–490

Jiang DQ, Liang SK, Chen DH (2009) Government regulation enforcement economic consequences in a transition economy: empirical evidence from Chinese listed companies implementing the split share structure reform. China J Account Res 2(1):71–99

Jones SL, Megginson WL, Nash RC, Netter JM (1999) Share issue privatisation as financial means to political and economic ends. J Financ Econ 53(2):217–253

Kazakevitcha G, Smyth R (2005) Gradualism versus shock therapy: (Re) interpreting the Chinese and Russian experiences. Asia Pac Bus Rev 11(1):69–81

Kim YIS, Ho M, Giles M. (2003) Developing institutional investors in People’s Republic of China. World Bank Country Study Paper

Kolari JW, Pynnönen S (2010) Event study testing with cross-sectional correlation of ARs. Rev Financ Stud 23(11):3996–4025

Kothari SP, Warner JB (2007) Econometrics of event studies. In: Eckbo BE (ed) Handbook of corporate finance: empirical corporate finance, 1st edn. Elsevier, North Holland

Landsman WR, Maydew EL (2002) Has the information content of quarterly earnings announcements declined in the past three decades? J Account Res 40(3):797–808

Li XL, Yang JP (2006) Analysis on issue of consideration in pilot stage of equity division reform. J Guangxi Univ Financ Econ 19(2):98–101 (in Chinese)

Li K, Wang T, Cheung YL, Jiang P (2011) Privatization and risk sharing: evidence from the split share structure reform in China. Rev Financ Stud 24(7):2499–2525

Liao L, Liu BB, Wang H (2011) Information discovery in share lockups: evidence from the Split-Share Structure Reform in China. Financ Manag 40(4):1001–1027

Lin JY (2004) Lessons of China’s transition from a planned economy to a market economy. Working Paper Series, Peking University

Liu W, Gao M (1999) Studies on China’s economic development. Shanghai Far East Press, Shanghai

Ljungqvist A (2007) IPO underpricing. In: Eckbo BE (ed) Handbook of corporate finance: empirical corporate finance. Elsevier, North-Holland

Ljungqvist A, Wilhelm WJ (2003) IPO pricing in the dot-com bubble. J Financ 58(2):723–752

Lo A, MacKinlay C (1990) When are contrarian profits due to stock market overreaction? Rev Financ Stud 3(2):175–206

Loderer C, Cooney J, Drunen L (1991) The price elasticity of demand for common stock. J Financ 46(2):621–651

Loughran T, Ritter J (2002) Why don’t issuers get upset about leaving money on the table in IPOs? Rev Financ Stud 15(2):413–443

Lu CJ, Wang KM, Chen HW, Chong J (2007) Integrating A- and B-share markets in China: the effects of regulatory policy changes on market efficiency. Rev Pac Basin Financ Mark Policies 10(3):309–328

Lu F, Balatbat MCA, Czernkowski RMJ (2008) Does consideration matter to China’s split share structure reform? Account Financ 52(2):439–466

MacKinlay AC (1997) Event studies in economics and finance. J Econ Lit 35(1):13–39

McKinnon RI (1994) Gradual versus rapid liberalization in socialist economies: financial policies and macroeconomic stability in China and Russia compared. Working paper. In: Proceedings of the World Bank annual conference on development economics 1993, The World Bank, Washington, DC, pp 63–94

McWilliams A, Siege D (1997) Event studies in management research: theoretical and empirical issues. Acad Manag J 40(3):626–657

Mikkelson WH, Partch MM (1985) Stock price effects and costs of secondary distributions. J Financ Econ 14(2):165–194

Mikkelson WH, Partch MM (1986) Valuation effects of security offerings and the issuance process. J Financ Econ 15(1–2):30–60

Mikkelson WH, Partch MM (1988) Withdrawn security offerings. J Financ Quant Anal 2:119–134

Mok HMK, Hui YV (1998) Underpricing and aftermarket performance of IPOs in Shanghai China. Pac Basin Financ J 6(5):453–474

Perotti E (1995) Credible privatisation. Am Econ Rev 85(4):847–859

Perotti E, Guney S (1993) The structure of privatization plans. Financ Manag 22(1):84–98

Pojezny N. (2006) Value creation in European equity carve-outs. Germany Deutscher Universitätsvlg Language (DUV), Verlag

Qi D, Wu WY, Zhang H (2000) Ownership structure and corporate performance of partially privatized Chinese SOE firms. Pac Basin Financ J 8(5):587–610

Rahman AM, Hassan MK (2013) Firm fundamentals and stock prices in emerging Asian stock markets: some panel data evidence. Rev Quant Finance Account 41(3):463–487

Ren GQ, Zhao YL (2009) Split Share Structure Reform effect model and empirical analysis. Front Econ China 4(3):461–477

Roenfeldt R, Griepentrog G, Pflaum C (1978) Further evidence on the stationarity of beta coefficients. J Financ Quant Anal 13(1):117–121

Salinger M (1992) Standard errors in event studies. J Financ Quant Anal 27(1):39–53

Scholes MS (1972) The market for securities: substitution versus price pressure and the effects of information on share prices. J Bus 45(2):179–211

Sun Q, Tong WHS (2003) China share issue privatisation: the extent of its success. J Financ Econ 70(2):183–222

Szewczyck S (1992) The intra-industry transfer of information inferred from announcements of corporate securities offerings. J Financ 47(5):1935–1945

Tawatnuntachai O, D’Mello R (2002) Intra-industry reactions to stock split announcements. J Financ Res 25(1):39–57

Tenev S, Zhang C (2002) Corporate governance and enterprise reform in China: building the institution of modern market. World Bank and International Finance Corporation, Washington, DC

Theobald M (1981) Beta stationarity and estimation period: some analytical results. J Financ Quant Anal 16(5):747–757

Tsai SL, Wu CC (1999) Financial development and economic growth of developed versus Asian developing countries: a pooling time-series and cross-country analysis. Rev Pac Basin Financ Mark Policies 2(1):57–81

Wang WWY, Chen JL (2006) Bargaining for compensation in the shadow of regulatory giving: the case of stock trading rights reform in China. Columbia J Asian Law 20:298–353

Wang XZ, Xu LXC, Zhu T (2004) State-owned enterprises going public: the case of China. Econ Transit 12(3):467–487

Wong SML (2006) China’s stock market: a marriage of capitalism and socialism. Cato J 26(3):389–424

Xia H, Cai X, Wu F (2006) Estimation of β coefficient and analysis of its stationarity. J Mod Account Audit 2(10):23–27

Xia XP, Mahmood F, Usman M (2010) Announcement effects of seasoned equity offerings in China. Int J Econ Financ 2(3):163–169

Yarrow G (1986) Privatization in theory and practice. Econ Policy 1(2):324–364

Yung C, Zender FJ (2010) Moral hazard, asymmetric information and IPO lockups. J Corp Financ 16(3):320–332

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Details of the 64 reforming groups

Group | No. | Group date | Interval in days | Group | No. | Group date | Interval in days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | 40 | Sep 12 05 | N/A | 33 | 26 | May 21 06 | 5 |

2 | 32 | Sep 18 05 | 6 | 34 | 30 | May 28 06 | 5 |

3 | 22 | Sep 26 05 | 8 | 35 | 20 | Jun 4 06 | 5 |

4 | 23 | Oct 9 05 | 13 | 36 | 21 | Jun 11 06 | 5 |

5 | 21 | Oct 16 05 | 5 | 37 | 24 | Jun 18 06 | 5 |

6 | 18 | Oct 23 05 | 5 | 38 | 36 | Jun 25 06 | 5 |

7 | 18 | Oct 30 05 | 5 | 39 | 32 | Jul 2 06 | 5 |

8 | 20 | Nov 6 05 | 5 | 40 | 8 | Jul 9 06 | 5 |

9 | 20 | Nov 13 05 | 5 | 41 | 12 | Jul 16 06 | 5 |

10 | 17 | Nov 20 05 | 5 | 42 | 8 | Jul 23 06 | 5 |

11 | 22 | Nov 27 05 | 5 | 43 | 8 | Jul 30 06 | 5 |

12 | 19 | Dec 4 05 | 5 | 44 | 9 | Aug 6 06 | 5 |

13 | 21 | Dec 11 05 | 5 | 45 | 8 | Aug 13 06 | 5 |

14 | 27 | Dec 18 05 | 5 | 46 | 6 | Aug 20 06 | 5 |

15 | 38 | Dec 22 05 | 4 | 47 | 8 | Aug 27 06 | 5 |

16 | 19 | Dec 30 05 | 5 | 48 | 8 | Sep 3 06 | 5 |

17 | 13 | Jan 8 06 | 5 | 49 | 7 | Sep 10 06 | 5 |

18 | 24 | Jan 15 06 | 5 | 50 | 5 | Sep 17 06 | 5 |

19 | 46 | Jan 22 06 | 5 | 51 | 11 | Sep 24 06 | 5 |

20 | 38 | Feb 12 06 | 5 | 52 | 6 | Oct 8 06 | 14 |

21 | 39 | Feb 19 06 | 5 | 53 | 6 | Oct 15 06 | 5 |

22 | 49 | Feb 26 06 | 5 | 54 | 7 | Oct 22 06 | 5 |

23 | 46 | Mar 5 06 | 5 | 55 | 5 | Oct 29 06 | 5 |

24 | 25 | Mar 12 06 | 5 | 56 | 7 | Nov 5 06 | 5 |

25 | 28 | Mar 19 06 | 5 | 57 | 12 | Nov 12 06 | 5 |

26 | 41 | Mar 26 06 | 5 | 58 | 14 | Nov 19 06 | 5 |

27 | 25 | Apr 2 06 | 5 | 59 | 7 | Nov 26 06 | 5 |

28 | 16 | Apr 9 06 | 5 | 60 | 10 | Dec 3 06 | 5 |

29 | 26 | Apr 16 06 | 5 | 61 | 11 | Dec 10 06 | 5 |

30 | 35 | Apr 23 06 | 5 | 62 | 12 | Dec 17 06 | 5 |

31 | 28 | May 7 06 | 14 | 63 | 22 | Dec 24 06 | 5 |

32 | 23 | May 14 06 | 5 | 64 | 32 | Dec 31 06 | 5 |

Appendix 2: Consideration

2.1 Appendix 2.1: Consideration forms

Consideration took various forms and could be used in different combinations.

The most popular forms are:

-

Shares Transfer (ST) the owners of NTAS give away certain NTAS to the holders of TAS. The existing investors of TAS receive free shares in proportion to their ownership in a firm from the corresponding owners of NTAS. But in ST, these shares are available to the existing shareholders for free and transferred from the NTAS instead of new shares. Effectively, an implementation of ST indicates a reduction of NTAS with zero revenues. Suppose an investor receives a consideration ratio of C ST per share held by the TAS owners and there are NT non-tradable A shares and T tradable A shares in a company, an application of ST can reduce the NTAS of this company by T × C ST .

-

Cash Payment (CP) the owners of NTAS pay Consideration in cash to the holders of TAS. Under this approach, there is no change in the shareholding structure but at the cash cost of the NTAS owners. NTAS owners opting for this payment method didn’t want to give away the shares and instead they paid RMB C CP per share the TAS owners own. In other words, they valued the shares that they would otherwise have paid under SP at T × C CP .

-

Recapitalization of retained earnings (RI) a listed company capitalizes its retained earnings and issue new equity shares. The owners of NTAS pay the holders of tradable shares the new equity shares they receive from the company. Under this approach, the number of total shares increases by (1 + T/NT × C RI ) times. Retained earnings capitalized are unavailable for future dividends. Therefore this approach is more of a wealth transfer from the future investors to the existing investors than from the NTAS owners to TAS owners.

-

European Put Warrants Transfer (PWT) the TAS holders have the right to put (sell) an underlying share to the NTAS holders at a certain strike price on or before a specified date at zero premium. Only when the exercise price (K PWT ) is greater than the market price around the mature date (P at-maturity ), will the put warrant be exercised. Under this approach, the NTAS owners are required to pay Consideration of T × (K PWT − P at-maturity )to the TAS owners on or before the expiry date. PWT protects the TAS owners when the market price falls below the exercise price.

Usually a put warrant is sold at a certain price, which reduces the warrant holder’s payoff by the cost. However in the case of China SSSR, the transfer of put warrant to the TAS holders is free of charge. The profit range for the TAS owners is (0, K PWT ) as the market price of share drops. Different from the approaches of ST, CP and RI, PWT brings the post-market factor into consideration.

-

European Call Warrants Transfer (CWT) The TAS holders have the right to buy the underlying share for an agreed price, on or before a specified date at zero premium. Only when the exercise price (K CWT ) set up front is lower than the market price around the mature date (P at-maturity ), will the call warrant be exercised. Under this approach, the NTAS owners are required to pay Consideration of T × (P at-maturity − K CWT )to the TAS owners on or before the expiry date. CWT allows the TAS owners to share profits when the market price rises up above the exercise price.

Like PWT, CWT is free of charge for the TAS holders and the profit range is (0, +∞) as the market price of share increases.

-

Share Split (SS) the owners of NTAS pay the holders of TAS the shares under their name from share split. A stock split increases the number of shares in a public company. Under this approach, the number of total shares increases by (1 + T/NT × C SS ) times. Compared to RI, the firm value is the same while the par value of the stock decreases.

The payments through ST, RI and SS implied a reduced state shareholding while the others didn’t. RI and SS increased the number of total shares outstanding. RI increased firm value as well but SS didn’t. Except for CWT and PWT which indicated the use of a real post-event price in a certain period, the others estimated a post-reform price.

2.2 Appendix 2.2: Valuation of consideration

The calculation of Consideration varied from company to company based on different assumptions. Many reform proposals didn’t provide a proper explanation of the calculation process or presented a proposed Consideration ratio without any explanation on how it was set. Li and Yang (2006) reported that FCR process has characters of diversified Consideration ways, various Consideration bases, unbalanced Consideration levels, frequent adjustments.

Consideration was generally based on the assumption of a substantial price drop in the aftermath of the implementation of the reform. Each company thus estimated its price/earning ratio or NAV once all shares were tradable and calculated, 1st the loss the TAS owners would incur as a result of the share price decline and 2nd the number of bonus shares the NTAS holders would have to offer to in order to offset the loss. To illustrate, see the process below:

-

1.

$$\begin{gathered} Value_{{pre{ - }event}} = T \times P_{pre} + NT \times P_{NT} \hfill \\ Value_{{post{ - }event}} = (T + NT) \times P_{post} \Rightarrow Loss_{{for{ - }TAS}} = (P_{pre} - P_{post} ) \times T \hfill \\ \end{gathered}$$

where T is the number of tradable shares and NT is the number of non-tradable shares, P pre is the market share price before the event and P post is the market share price after the event.

-

2.

Suppose C refers to the bonus share received for by each TA held, therefore \((P_{pre} - P_{post} ) \times T = C \times T \times P_{post} \Rightarrow C = \frac{{(P_{pre} - P_{post} )}}{{P_{post} }}\), indicating TAS would receive \(\frac{{P_{pre} - P_{post} }}{{P_{post} }}\) shares for every premarket TA held. This is the basic model for the calculation of Consideration.

The valuation of Consideration depends on the estimation of P post , which, generally speaking, is determined by how each firm estimated its post-event P/E ratio or NAV.

Various Considerations forms may differ in presenting Considerations but in general follows the idea that the value before and after the event should be the same and Consideration should compensate for the aftermarket loss to the TAS owners. Shown below is the theoretical valuations of Consideration for various Consideration forms (on per share basis) although in most proposals the details were not available.

-

Consideration for Share Transfer: \(C_{ST} = \frac{{(P_{pre} - P_{post} )}}{{P_{post} }} = \frac{{P_{pre} }}{{P_{post} }} - 1\)

-

Derivation of Consideration for Recapitalised Issuance:

$$\begin{gathered} Value_{{pre{ - }event}} = T \times P_{pre} + NT \times P_{NT} \hfill \\ Value_{{post{ - }event}} = (T + NT + T_{RT} + NT_{RT} ) \times P_{post} , \hfill \\ \end{gathered}$$where T RT /NT RT is the number of additional shares from the recapitalised earnings allocated proportionally to the holders of TAS/NTAS.

$$\begin{gathered} P_{pre} \times T - P_{post} \times (T_{RT} + T) = C_{RI} \times T \times P_{post} \hfill \\ C_{RI} = \frac{{P_{pre} \times T - P_{post} \times T_{RT} - P_{post} \times T}}{{T \times P_{post} }} = \frac{{P_{pre} }}{{P_{post} }} - \frac{{T + T_{RT} }}{T} \hfill \\ \end{gathered}$$ -

Derivation of Consideration for Share Split:

$$\begin{gathered} Value_{{pre{ - }event}} = T \times P_{pre} + NT \times P_{NT} \hfill \\ Value_{{post{ - }event}} = {{(T + NT) \times P_{post} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{(T + NT) \times P_{post} } {R_{SS} ,}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {R_{SS} ,}} \hfill \\ \end{gathered}$$where R SS is share split ratio.

$$\begin{gathered} P_{pre} \times T - {{T \times P_{post} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{T \times P_{post} } {R_{SS} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {R_{SS} }} = C_{SS} \times T \times P_{post} \hfill \\ C_{SS} = \frac{{P_{pre} \times T - P_{post} \times {T \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {T {R_{SS} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {R_{SS} }}}}{{T \times P_{post} }} = \frac{{P_{pre} }}{{P_{post} }} - \frac{1}{{R_{SS} }} \hfill \\ \end{gathered}$$ -

Derivation of Consideration for Cash Payment:

$$\begin{gathered} Value_{{pre{ - }event}} = T \times P_{pre} + NT \times P_{NT} \hfill \\ Value_{{post{ - }event}} = (T + NT) \times P_{post} \hfill \\ (P_{pre} - P_{post} ) \times T = C_{CP} \times T \hfill \\ \Rightarrow C_{CP} = P_{pre} - P_{post} \hfill \\ \end{gathered}$$In a proposal using PWT/CWT as Consideration, a strike price instead of a Consideration is provided. The potential aftermarket loss to the holders of TAS depends on the maturity price in the future (P at-maturity ) rather than the market price immediately after the event (P post ).

-

Derivation of Consideration for Put Warrant:

$$\begin{gathered} Value_{{pre{ - }event}} = T \times P_{pre} + NT \times P_{NT} \hfill \\ Value_{{post{ - }event}} = (T + NT) \times P_{{at{ - }maturity}} \hfill \\ (P_{pre} - P_{{at{ - }maturity}} ) \times T = Max(0,K_{PWT} - P_{{at{ - }maturity}} ) \times C_{PWT} \times T, \hfill \\ \end{gathered}$$subject to C PWT × T is no more than the maximum shares the warranties holders can sell.

$$\Rightarrow C_{PWT} = \frac{{(P_{pre} - P_{at - maturity} ) \times T}}{{Max(0,K_{PWT} - P_{at - maturity} ) \times T}} = \frac{{(P_{pre} - P_{at - maturity} )}}{{Max(0,K_{PWT} - P_{at - maturity} )}}$$ -

Put warrant won’t be exercised if K PWT < P at-maturity

-

Put warrant will be exercised if K PWT > P at-maturity , therefore\(\Rightarrow C_{PWT} = \frac{{P_{pre} - P_{at - maturity} }}{{K_{PWT} - P_{at - maturity} }}\)

-

Derivation of Consideration for Call Warrant:

$$\begin{gathered} Value_{{pre{ - }event}} = T \times P_{pre} + NT \times P_{NT} \hfill \\ Value_{{post{ - }event}} = (T + NT) \times P_{{at{ - }maturity}} \hfill \\ (P_{pre} - P_{{at{ - }maturity}} ) \times T = Max(0,P_{{at{ - }maturity}} - K_{CWT} ) \times C_{CWT} \times T, \hfill \\ \end{gathered}$$subject to C CWT × T is no more than the maximum shares the warranties holders can buy.

-

$$\Rightarrow C_{CWT} = \frac{{(P_{pre} - P_{at - maturity} ) \times T}}{{Max(0,P_{at - maturity} - K_{CWT} ) \times T}} = \frac{{(P_{pre} - P_{at - maturity} )}}{{Max(0,P_{at - maturity} - K_{CWT} )}}$$

-

Call warrant won’t be exercised if P at-maturity < K CWT

-

Call warrant will be exercised if P at-maturity > K CWT , therefore \(\Rightarrow C_{CWT} = \frac{{P_{pre} - P_{at - maturity} }}{{P_{at - maturity} - K_{CWT} }}\).

2.3 Appendix 2.3: Summary of the sample consideration

Consideration plan | Total | % | Average raw consideration ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Shares Transfer (ST) only | 439 | 73.46 | 0.307 share per TAS | |

Cash Payment (CP) only | 6 | 1.00 | ¥1.1 (≈ £0.073) per TAS | |

Recapitalisation Issues (RI) only | 92 | 15.19 | 0.58 share per TAS | |

Put/Call Warrant Issues (P/C) only | 1 | 0.17 | 0.8 share per TAS | |

Share Split (SS) only | 5 | 0.83 | 0.63 share per NTAS | |

Combinations | Total | 56 | 9.36 | N/A |

CP + P/C + ST | 1 | 0.17 | N/A | |

CP + ST | 27 | 4.51 | N/A | |

CP + RI | 1 | 0.17 | N/A | |

RI + P/C | 3 | 0.50 | N/A | |

RI + ST | 14 | 2.34 | N/A | |

P/C + ST | 10 | 1.67 | N/A | |

Total | 599 | |||

Appendix 3: Statistical tests

There are three statistical tests employed in this paper.

-

1.

BW: the crude dependence adjustment test (Brown and Warner 1980)

-

2.

MP: the time-series adjustment test (Mikkelson and Partch 1988)

-

3.

Rank: the rank test (Corrado 1989)

Even relatively moderate cross-sectional dependence could cause Type I errors (Salinger 1992, Aktas et al. 2007; Kothari and Warner 2007; Kolari and Pynnönen 2010). Event clustering is a big problem in the SSSR. The MP test, which assumes cross-sectional independence, therefore should be carefully treated when there is serious cross-sectional dependence.

A large residual autocorrelation could lead to Type I errors. Figure below shows the histogram of the 1-day lag residual autocorrelations from the estimation periods for all the sample companies, with a step of 0.05.

The sample autocorrelation converges around 0.025 with a maximum of 0.25. Generally speaking, the problem of time-series dependence is not very serious, indicating the BW test, which assumes time-series independence, may make fewer Type I errors and is more likely to give better significance.

The rank test examines whether the position of the ARs in event-window are significantly away from the centre position over the combined period (estimation period plus event period). As the rank test is free of distribution and doesn’t require independence across securities or over time, it provides a robust alternative to BW and the MP tests.

Appendix 4: The results of cross-sectional multiple regressions

Appendix 5: Conversion of original considerations ratios into equivalent shares offered (formula)

Consideration plan | Consideration valuation | Equivalent shares offered |

|---|---|---|

Shares Transfer (ST) | \(C_{ST} = \frac{{P_{pre} - P_{post} }}{{P_{post} }}\) | C ′ ST = C ST |

Recapitalisation Issues (RI) | \(C_{RI} = \frac{{P_{pre} }}{{P_{post} }} - \frac{{T_{RT} + T}}{T}\) | \(C_{ST}^{{\prime }} = {{C_{RI} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{C_{RI} } {\left( {\frac{{T_{RT} + T}}{T}} \right)}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\left( {\frac{{T_{RT} + T}}{T}} \right)}}\) |

Share Split (SS) | \(C_{SS} = \frac{{P_{pre} }}{{P_{post} }} - \frac{1}{{R_{SS} }}\) | \(C_{ST}^{{\prime }} = {{C_{SS} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{C_{SS} } {R_{SS} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {R_{SS} }}\) |

Cash Payment (CP) | C CP = P pre − P post | \(C_{ST}^{{\prime }} = {{C_{CP} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{C_{CP} } {P_{post} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {P_{post} }}\) |

Put Warrant Issues (PWT) | \(C_{PWT} = \frac{{P_{pre} - P_{{at{ - }maturity}} }}{{K_{PWT} - P_{{at{ - }maturity}} }}\) if exercised | \(C_{ST}^{{\prime }} = C_{PWT}\) |

Call Warrant Issues (CWT) | \(C_{CWT} = \frac{{P_{pre} - P_{{at{ - }maturity}} }}{{P_{{at{ - }maturity}} - K_{CWT} }}\) if exercised | \(C_{ST}^{{\prime }} = C_{CWT}\) |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zeng, Y., McLaren, J. The impact of large public sales of Government assets: empirical evidence from the Chinese stock markets on a gradual and offer-to-get approach. Rev Quant Finan Acc 45, 137–173 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-014-0433-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-014-0433-9

Keywords

- Chinese state-owned enterprises

- Split-Share Structure Reform

- Gradualism

- Offer-to-get approach

- Consideration