Abstract

The purpose of this paper was to investigate a model for describing the relationships between the extent to which learning environments are activating and students’ interaction with teachers and peers, sense of belonging, and study success. It was tested whether this model holds true for both ethnic minority students and ethnic majority students. A total of 523 students from four different universities completed a questionnaire. Structural equation modeling (Amos) was used to test the model. The model that best describes the relationships in the group of ethnic minority students (N = 145) was shown to be different than the model that best fits the group of majority students (N = 378). Ethnic minority students appeared to feel at home in their educational program if they had a good formal relationship with teachers and fellow students. Ethnic minority students’ sense of belonging to the institution nevertheless did not contribute to their study progress. On the other hand, in majority students, informal relationships with fellow students were what led to a sense of belonging. In these students, the sense of belonging did further academic progress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the past decade(s), higher education in Western societies has become ethnically more diverse. Democratization of higher education, in combination with long-term effects of postcolonial and labor migration have led to an increasing number of students in general, and to an increase of ethnic minority students in particular (Severiens and Wolff 2009). In the Netherlands for example the number of first year students of non-Western descent, who in the Dutch context are considered as ethnic minority students, more than doubled up to a total number of almost 16,000 students from 1997 to 2006. This caused a relative increase from 8% non-Western influx of the total number of first year students in 1997 to 13% in 2006 (Statistics Netherlands).

These ethnic changes in the student population raise the question how well this group of minority students is performing. Does access to higher education also mean that chances for success are more or less the same for both ethnic majority and non-Western ethnic minority students? International data generally show that study careers of ethnic minority students are less successful. They earn less credits in the same amount of time (Hofman and Van den Berg 2003; Severiens and Wolff 2008; Swail et al. 2003) and they on average have lower completion rates in higher education compared to non-minority students (Crul and Wolff 2002; Eimers and Pike 1997; Hobson-Horton and Owens 2004; Jennissen 2006; Just 1999; Van den Berg 2002; Van den Berg and Hofman 2005). The present study explores a possible reason for differences in study success.

Quality of Interactions

In international literature on academic progress and student attrition Tinto’s model on student retention (Tinto 1975, 1993, 1997, 1998) is very important. Tinto considers the educational institution to consist of an academic system and a social system, and makes a distinction between academic and social integration. In Tinto’s original theory (1975) academic integration is seen as grade performance and students’ intellectual development during the college years. Social integration refers to informal peer group associations, semi-formal extracurricular activities and interaction with faculty and administrative personnel within the college. Within the years Tinto extended and revised his theory of student departure. In his revised model on student retention Tinto (1993) distinguishes between formal and informal forms of integration. He also revised the determination of academic and social integration. Academic integration is now seen as academic achievement (formal academic integration) and interaction with the faculty (informal academic integration). Social integration refers to extracurricular activities (formal social integration) and contact with peers (informal social integration). Tinto’s concepts of academic and social integration are important concepts in the research area examining diversity in higher education (Tinto 1993; see also Severiens and Wolff 2009). A certain level of academic and social integration is required of students who wish to persist in college and to graduate successfully (Tinto 1993). Tinto’s model posits that, all other things remaining equal, the higher the degree of integration into the academic and social communities of the institute, the greater the likelihood of persistence.

Beekhoven et al. (2002) demonstrated that there is some conceptual inconsistency regarding academic and social integration. In part, this might be a result of the revision of Tinto’s theory. Beekhoven et al. argue that while Tinto (1993) defines ‘interaction with faculty’ as academic integration, others still define it as social integration (Berger and Milem 1999; Braxton et al. 2000). Some authors (Pascarella et al. 1983) make a distinction between two kinds of faculty contacts: on the one hand, contacts with faculty that involve discussion and advice are seen as academic integration; on the other hand, non-classroom interaction with faculty and informal social contacts with faculty are seen as social integration. The measurement of the concepts academic and social integration also seems to be different in various studies according to Beekhoven et al. (2002). Cabrera et al. (1992) for example measured academic integration by students’ academic experience and performance. In other studies academic integration is measured by questions on students’ estimation of their academic and intellectual development and their perception of faculty concern for teaching and student development (Berger and Milem 1999), academic involvement and success (Eimers and Pike 1997) or an extensive indicator including grades, intellectual development, quality of education and contacts with faculty concerning discussion and advice (Pascarella et al. 1983). The indicators used for social integration are also diverse as outlined by Beekhoven et al. (2002). For example, Cabrera et al. (1992) used two questionnaire items concerning friendship with other students. In a later study Nora and Cabrera (1996) used a nine-item scale measuring overall satisfaction with the social life of the students at campus, an easiness in making friends, and the influence of such relationships on students’ intellectual growth. Both Berger and Milem (1999) and Braxton et al. (2000) estimated social integration by measuring peer groups relations and out-of-class interactions with faculty members. Eimers and Pike (1997) used questions focused on the amount of time students spent on campus and the strength of their peer acquaintances to measure social integration, and Pascarella et al. (1983) measured social integration as the frequency and quality of a student’s relationship with peers, the quality of their non-classroom faculty interactions, and the frequency of their informal social contact with the faculty.

These differences in measurement of the concepts academic and social integration can be a possible explanation for the variety of results in terms of differences in integration levels, sometimes with majority students scoring higher (Beekhoven 2002; Eimers and Pike 1997), sometimes with no score differences (Berger and Milem 1999) occurring, and sometimes with minority students scoring higher (Nora and Cabrera 1996). Similarly, while some studies found a relationship between integration and study progress (Berger and Milem 1999), others did not (Nora and Cabrera 1996) or found only a weak relationship (Beekhoven 2002; Beekhoven et al. 2002).

In an earlier qualitative study conducted in the Netherlands (Severiens et al. 2006),Footnote 1 138 students (ethnic minority as well as majority students) were interviewed and asked about their social and academic experiences in different periods during their study. The results showed that quality of interactions among peers and between peers and teachers were important to obtain good study results. Similar to Tinto’s (1993) formal and informal integration a distinction could be made between formal and informal interaction between peers and between peers and teachers. On the basis of the interviews scales were constructed measuring formal interaction with teachers, informal interaction with teachers, formal interaction with peers and informal interaction with peers.

These interaction scales were used in a study (Severiens and Wolff 2008) in which we examined differences between ethnic minority students and their majority counterparts in terms of their interaction with teachers and peers and related these to their quality of learning. Quality of learning was defined as the number of credits earned in the first year of the study program, students’ average grades and students’ approaches to learning. Based on the reports of minority and majority students, they were equally satisfied with the formal and informal relationships they had with peers and equally dissatisfied with the relationships they had with teachers. However, the relationship between interaction and study progress (i.e. the number of credits earned in the first year of the study program) as one of the indicators of quality of learning varied according to ethnic background. In the group of minority students, no significant links were observed between interaction and number of credits, indicating that study progress could not be predicted based on the quality of interaction. In the group of majority students on the other hand, formal relationships with teachers and formal relationships with peers positively affected study progress and informal relationships with teachers negatively affected study progress.

In this study, however, the model only explained a relatively small degree of variance in study progress. In order to improve the explanatory power of the model, it obviously needs to include additional factors. In the present study, therefore, two factors that may be important in explaining differences in study progress between ethnic minority and majority students have been added to the model. These factors are ‘sense of belonging’ and the ‘learning environment’. In the remainder of this introduction, these factors will be described in more detail.

Sense of Belonging

Previous research has shown that ethnic minority students generally feel less at home in their educational program compared to their fellow students from the dominant culture. For example, various US studies demonstrated that African American students and Asian Pacific or Hispanic/Latino students feel less strongly that they belong in a program than white American students (Hurtado and Carter 1997; Johnson et al. 2007). In another study, Hurtado (1994) found that many Hispanic students feel that they do not ‘fit in’ on their campus. A study by Read et al. (2003) focused on the extent to which ethnic minority students actually do fit in at universities and the degree to which ‘academia’ is foreign to them. They reported that the presence of students of a similar age, class, gender or ethnicity was not necessarily sufficient to make them feel comfortable in the university environment, and thus to make them feel like they ‘belong’. Moreover, in this study the ‘non-traditional’ students in terms of class, maturity and ethnicity felt most alienated by academic culture itself. Apparently, students who come from backgrounds where there is little history of participation in higher education can find academic culture particularly bewildering, and may lack the support and guidance that comes from having friends or family that have been through the experience of attending university. Zepke and Leach (2005) argue that these students often experience ‘a lack of socialization’, ‘alienation’, ‘difficulty making friends’, and ‘feeling homesick’, which causes them to feel that they do not belong.

It has been demonstrated that the prevailing climate within an institution has an impact on student outcomes. Studies investigating drop-outs have shown that for ethnic minority students in particular, feeling like one does not belong (often referred to in terms of ‘not fitting in’) is an important reason for dropping out (Just 1999; Swail et al. 2003; Zea et al. 1997). Hurtado and Carter (1997) found that a hostile climate had a negative influence on Latino students’ sense of belonging. Just also argues that the perception of a hostile climate on campus can directly affect minority students’ sense of belonging, which subsequently can have an impact on their performance.

In studies which have investigated students’ sense of belonging in relation to their study progress and persistence in higher education, the theoretical framework has often been based on the concept of institutional habitus (Berger 2000; Thomas 2002; Zepke et al. 2006). According to Berger each campus is composed of students who generally share a common habitus which to some extent is congruent with the organizational habitus of that institution. Berger theorizes that students who already share routinized behavior preferences, or who are particularly adept at reading normative cues, are more likely to easily make the adjustments necessary to fit in with the dominant peer group(s). The similarity of shared backgrounds, aspirations, and attitudes among students who constitute the dominant majority on campus probably makes it easier for these students to adapt to campus life, whereas adaptation is likely to be more difficult for those who come from different backgrounds. Thomas states that institutional culture can make learners feel like fish in water or fish out of water. In other words, if students feel that they do not fit in, that their social and cultural practices are inappropriate, and that their tacit knowledge is undervalued, they may be more inclined to withdraw early (i.e. they feel like fish out of water). This line of thinking is confirmed in the previously mentioned study by Zepke et al. (2006), in which students reported that feeling they did not belong was an important reason for considering withdrawal.

The conclusion from this area of research is that ethnic minority students appear to feel less at home in their educational programs compared to majority students, and that this feeling may result in negative student outcomes, such as poor study progress and early withdrawal.

The Link Between a Sense of Belonging and Interaction

Given these two theoretical frameworks (i.e. the work of Tinto (1993, 1997, 1998) and the literature on sense of belonging) and their respective empirical support, the question can then be asked as in what ways the concept of sense of belonging on the one hand and quality of interactions on the other hand are interrelated. In their study on sense of belonging, Johnson et al. (2007) argued that positive peer and faculty interaction influences students’ sense of belonging by making complex environments feel more socially and academically supportive. The results of their study, however, did not confirm this argument. On the other hand, Hoffman et al. (2003) were able to identify a positive relationship between supportive faculty interactions in both academic and social environments, and students’ subsequent sense of belonging. Furthermore, participation in extracurricular activities and membership in campus sub-environments were found to contribute to students’ sense of belonging in a study by Hurtado and Carter (1997). Based on these findings, it might be expected that teacher and peer interactions possibly form antecedents of students’ sense of belonging. Additionally, some studies have shown that a sense of belonging is more vital for minority students (Just 1999; Swail et al. 2003; Zea et al. 1997). This could imply that the interrelationships between teacher and peer interaction, sense of belonging and study success may be different for minority and majority students.

The Learning Environment

In addition to examining links between interaction and sense of belonging and finding out whether sense of belonging explains study progress to a greater extent, the present study aims to follow up on a question left unanswered in our former study (Severiens and Wolff 2008). This question concerns the role of the learning environment. Given the possible importance of sense of belonging and peer and teacher interaction with regard to study success, it is relevant to examine stimulating factors in the learning environment. What type of learning environment enhances feelings of belonging? And what type of learning environment fosters quality interactions among students and between students and their teachers?

The Link Between the Learning Environment, Interaction, Sense of Belonging and Study Success

Most studies examining the link between the learning environment on the one hand and sense of belonging or quality interactions on the other hand show that learning environments that can be characterized as activating and (or) cooperative environments, help students to integrate, experience a sense of belonging and achieve good study results. For example, in their study about learner centeredness and student retention, Zepke et al. (2006) showed how learner-centered education improves retention and completion rates. Their study confirmed earlier findings by Yorke and Thomas (2003). Learner centeredness is described in terms of high quality teaching in general and catering to diverse learning preferences. In other words, for the learning environment to stimulate retention, it should adapt to the diverse backgrounds of students.

Braxton et al. (2000) have studied the relationship between active learning behavior in the classroom on the one hand, and social integration (measured by peer group relations and out-of-class interactions with faculty members), involvement, and the decision to continue studying on the other hand. Their descriptive study showed that active learning behavior indeed fosters social integration. Moreover, social integration was positively related to students’ decisions to remain in their chosen program. Prince (2004) conducted a study that focused on the relationship between activating learning environments and interaction. This study reported that active learning (i.e. collaborative and cooperative learning) promoted the quality of social interaction. The same was found by Johnson et al. (1998). In a study by Umbach and Wawrzynski (2005) it similarly was concluded that at institutions where faculty members use active and collaborative learning techniques, levels of engagement and student learning were higher.

The main conclusion from this short overview is that activating and cooperative learning environments foster peer and faculty interaction, and in turn, that this interaction positively affects generic learning outcomes such as levels of engagement and the decision to continue studying. In a similar vein, activating learning environments seem also to promote a sense of belonging as well as retention. What we do not know, is whether activating learning environments stimulate peer and teacher interaction and sense of belonging in a similar way, or to a similar extent, in groups of students from different ethnic backgrounds.

Aim of the Present Study

Figure 1 summarizes the research literature regarding the links between the learning environment, teacher and peer interactions, sense of belonging and study success. The present study aims to examine these links, as well as possible differences between students from different ethnic backgrounds. First, the theoretical model (see Fig. 1) will be tested in the full sample. Next, the model will be tested in groups of ethnic minority and majority students.

Based on the literature, all relationships in the model are hypothesized to be positive. In addition, some of the studies suggest that high levels of sense of belonging, as well as peer and teacher interactions, may be more important for minority students (Eimers and Pike 1997; Just 1999; Swail et al. 2003; Zea et al. 1997). Therefore, it is expected that the relationships in the model as tested in the group of minority students will be stronger than the relationships in the group of majority students.

The research questions are the following:

-

1.

To what extent can the positive links between the learning environment, peer and teacher interactions, sense of belonging and study success as described in the theoretical model be confirmed?

-

2.

Does the model hold true for both the group of minority students and the group of majority students? And if not, are the relationships different in a group minority students compared to the relationships in a group of majority students?

Method

Participants and Procedure

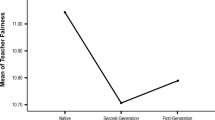

The participants were 523 first year university students from four different universities in the Netherlands (145 ethnic minority students and 378 majority students). Each participant completed an online version of a questionnaire measuring quality of interactions, sense of belonging and the type of learning environment. The response rate was 33%. Background information on these students is provided in Table 1. Our former paper (Severiens and Wolff 2008) made use of data collected in the same empirical study. That paper investigated the links between quality of interactions and three indicators of quality of learning. The present paper expands on this previous study by including sense of belonging and the learning environment in an attempt to increase the explanatory power of the model.

First-year students were chosen because the drop-out rate between the first and second year is relatively high, namely approximately 10%. First-year students thus provide the most varied picture of students in higher education.

The distinction between majority and minority students was made on the basis of the definition used by Statistics Netherlands (CBS). According to CBS an individual belongs to an ethnic minority group if at least one parent was born outside the Netherlands. Most minority students in our sample belong to a non-Western minority group, as they or their parents were born in Surinam, Turkey, the Netherlands Antilles or Morocco. Because these sub-groups were represented by relatively small samples—varying from nine to 27—it was not possible to compare the individual ethnic groups with each other.

Measures

Based on previous research on activating learning environments (Braxton et al. 2000), a scale was constructed to measure the extent to which a learning environment is activating. Items measuring the type of teaching (e.g. ‘how often did you have to work cooperatively in small groups of students in the last year?’), type of exams (e.g. ‘how often did you take open-ended exams in the last year?’) and teacher’s behavior (e.g. ‘teachers make us think about how to study’) were included. Students were asked to rate each of the items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). This eight-item scale yielded an average of 3.00, with a standard deviation of .67 (see Table 2 for the scores of ethnic minority and majority students) and a Cronbach’s alpha of .67.

The operational definition of teacher and peer interactions was based on an earlier qualitative study conducted in the Netherlands (Severiens et al. 2006), in which 138 students (ethnic minority as well as majority students) were interviewed and asked about their social and academic experiences in different periods during their study. In order to create a valid and reliable instrument in the context of Dutch Higher Education, excerpts from these interviews were used to develop four sets of items measuring formal and informal interactions with teachers and peers (Severiens et al. 2006). Students were asked to rate each of the items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not true at all) to 5 (completely true). The formal teacher interaction scale consisted of seven items, with an average scale score of 2.71, a standard deviation of .73 (see Table 2) and a Cronbach’s alpha of .72. Informal interaction with teachers is measured with eight items. This scale yielded an average of 2.25, with a standard deviation of .75 and a Cronbach’s alpha of .80. The formal peer interaction scale (k = 8) yielded an average of 3.47, with a standard deviation of .62 and a Cronbach’s alpha of .79. The scale measuring informal interaction with peers consisted of five items. The average scale score was 3.71, the standard deviation was .83 and the Cronbach’s alpha was .87. In Table 3 all scale items are presented.

Students’ sense of belonging was measured using a six item scale developed for this study. Item examples are ‘I feel at home at this university’ and ‘I enjoy the atmosphere at this university’. Students were asked to rate each of the items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not true at all) to 5 (completely true). This scale yielded an average of 3.70, with a standard deviation of .70 and a Cronbach’s alpha of .76.

Study success was indicated by study progress. From previous research it is known that ‘the number of credits earned’ is an appropriate measure for students’ study progress in the Netherlands (Beekhoven et al. 2002; Van den Berg and Hofman 2005). Therefore, study progress was measured by the number of credits (varying from 0 to 60) students had earned after 1 year of study. This information was obtained from the academic records of the universities.

Method of Analysis

The research questions were answered using linear structural modeling analyses using Amos (Arbuckle and Wothke 1999). This method makes it possible to test specific hypotheses about the relationships between the relevant variables. Amos provides a number of relevant statistics, including a chi-square statistic (χ2) that can be used to test whether the empirical data sufficiently fit a proposed theoretical model. It has generally been accepted that χ2 should be expressed relative to the corresponding degrees of freedom. Among others, Carmines and McIver (1981) suggested that, before rejecting a model as ill-fitting, χ2 should be two or three times greater than the degrees of freedom (Punnett and Van der Beek 2000). In addition, other statistics have been developed for the evaluation of a particular model. Next to χ2, we used the comparative fit index (CFI), with a cut-off value of >.95 (Hu and Bentler 1999) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), with guidelines proposed by MacCallum et al. (1996). RMSEA values of less than .05 indicate a close fit, values ranging from .05 to .08 indicate a fair fit, values from .08 to .10 indicate a mediocre fit, and values greater than .10 indicate a poor fit between the observed data and the specified theoretical model.

Results

Linear structural modeling analyses were used to determine the interrelationships between the learning environment, the four types of interaction, students’ sense of belonging and their study progress as described in Fig. 1.

As we are interested in the unique contribution of each of the four types of interaction, we allowed for the error-covariances between all four measures to covary. The results for this hypothesized model were chi-square = 10.38, df = 4, p = .03; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .06. On the basis of the chi-square, the hypothesized model is rejected. However, the other fit measures indicate a fair fit. To improve the model, the non-significant relationship between learning environment and credits was eliminated. This resulted in a close fit based on all fit measures (Fig. 2). The results were chi-square = 10.80, df = 5, p = .06; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .05 (see Table 4 for standardized regression coefficients).

Given the focus on possible differences between ethnic minority and majority students, it was tested whether the results obtained from the full sample fit the group of ethnic minority students and the group of majority students separately (see Fig. 2).

First, the model was tested for ethnic minority students.Footnote 2 The accepted model for the total group of students (N = 523) fit the group of minority students (N = 145) well and could be accepted: chi-square = 3.41, df = 5, p = .64. Furthermore, RMSEA is .00 and the CFI is 1.00. The model explained 2% of variance in study progress. Figure 3 shows the paths in the model for ethnic minority students. The statistically significant paths were from:

-

learning environment to formal teacher interaction (standardized coefficient of .42);

-

learning environment to informal teacher interaction (standardized coefficient of .42);

-

learning environment to formal peer interaction (standardized coefficient of .27);

-

formal teacher interaction to sense of belonging (standardized coefficient of .28);

-

formal peer interaction to sense of belonging (standardized coefficient of .36);

The model showed that the more activating the learning environment is the more minority students have high quality formal relationships with their teachers. An activating learning environment also had a positive impact on minority students’ informal contacts with their teachers. The quality of collaborative work with fellow students was positively influenced by a more activating learning environment. The extent to which minority students feel at home at the institution was only influenced by the formal forms of interaction. The better the formal contacts with teachers and fellow students, the more minority students felt they belonged at the institution. Yet, what was remarkable in the accepted model for minority students was that their study progress could not be predicted from the learning environment nor from their sense of belonging. It thus appeared that the extent to which minority students felt that they belonged at the institution did not have any consequence for their study progress.

Second, the model was tested for the group of majority students. The accepted model for the total group (N = 523) of students (which also closely fit in the group of ethnic minority students separately) did not fit the group of majority students (N = 378) well and could not be accepted: chi-square = 14.75, df = 5, p = .01; RMSEA = .07; CFI = .99. Modification indices thereafter suggested that a link should be included between informal teacher interaction and credits to obtain a model fit. This resulted in a model with a fair fit: chi-square = 8.68, df = 4, p = .07; RMSEA = .06; CFI = 1.00. To improve the model, the non-significant relationship between informal teacher interaction and sense of belonging was eliminated. This amendment indeed resulted in a model with a close fit: chi-square = 9.25, df = 5, p = .10; RMSEA = .05; CFI = 1.00 (see Fig. 4). The model explained 11% of variance in study progress. The statistically significant paths were from:

-

learning environment to formal teacher interaction (standardized coefficient of .44);

-

learning environment to informal teacher interaction (standardized coefficient of .47);

-

learning environment to formal peer interaction (standardized coefficient of .32);

-

learning environment to informal peer interaction (standardized coefficient of .22);

-

informal peer interaction to sense of belonging (standardized coefficient of .39);

-

informal teacher interaction to credits (standardized coefficient of −.12);

-

sense of belonging to credits (standardized coefficient of .34).

As for minority students, the model for the majority students showed that the more activating the learning environment is, the more majority students had high-quality formal contacts with their teachers as well as informal contacts with their teachers. The quality of collaborative work with fellow students was positively influenced by a more activating learning environment. The learning environment also influenced the quality of informal contacts with fellow students in the case of majority students. The more activating the learning environment, the better majority students’ contacts with their fellow students were. The extent to which majority students felt at home at the institution was only influenced by informal social interaction. The better the quality of informal contacts with fellow students, the more majority students felt they belonged at the institution. The study progress of majority students could be predicted based on their sense of belonging. The more majority students felt that they belonged at the institution, the more credits they earned. Their study progress was also influenced by the informal relationships with teachers but in a negative way (see the negative path from informal teacher interaction to study progress). This means that, on average, majority students who reported informal interactions with their teachers earned fewer credits than students who did not report such interactions.

Discussion

In a previous study (Severiens and Wolff 2008), a model was tested that describes a direct link between four forms of interaction on the one hand and three indicators of quality of learning on the other hand. To follow up on these findings, we first investigated whether sense of belonging did explain study progress in the group of minority students in this study. We expected that formal and informal peer and teacher interactions would be possible antecedents of students’ sense of belonging, based on findings by Hoffman et al. (2003) and Hurtado and Carter (1997). Secondly, the role of the learning environment was investigated as well. From previous research it is known that, in general, learning environments that can be characterized as activating and (or) cooperative, help students integrate (Braxton et al. 2000; Johnson et al. 1998; Prince 2004), help them feel they belong (Umbach and Wawrzynski 2005) and achieve good study results (Yorke and Thomas 2003; Zepke et al. 2006). From this earlier research, we developed the theoretical model as presented in Fig. 1. The present study investigated the relationships between these factors, and possible differences between students from different ethnic backgrounds.

Aside from one link in the model (the direct relationship between learning environment and credits), the model fit the data well. This model was accepted for the total group of students (N = 523), thereby answering our first research question positively, namely that positive relationships between the learning environment, peer and teacher interactions, sense of belonging and study success could be identified. To answer our second research question, that is whether the model hold true for both ethnic minority as well as ethnic majority students separately, the full sample model was tested in the group of ethnic minority students and in the group of majority students separately. The results showed that the model that describes the relationships in the group of ethnic minority students is not the same as the model that fits the group of majority students. Ethnic minority students appeared to feel at home in their educational program if they have good formal relationships with teachers and fellow students. The extent to which ethnic minority students felt they belonged at the institution, however, appeared not to influence their study progress. Ethnic majority students’ sense of belonging on the other hand was not fostered by any formal relationships. Instead, the better the informal contacts with fellow students were, the more majority students felt at home. Moreover, sense of belonging in the group of majority students furthered their study progress. Their study progress was also influenced by the informal relationships with teachers, but in a negative way. This result was already observed in the study of Severiens and Wolff (2008). As Severiens and Wolff theorized, it is not unlikely that this relationship should be interpreted the other way around: teachers approach majority students with lower grades more often than they approach students who perform well.

What was confirmed by the present study was our expectation that teacher and peer interactions were antecedents of students’ sense of belonging, and that the interrelationships between interaction, sense of belonging and study success are different for minority students compared to their majority counterparts. However, the present study showed that the extent to which a learning environment was activating did not influence students’ sense of belonging directly. An activating learning environment did foster quality interactions among students and between students and their teachers. Different forms of interactions then led to a sense of belonging on the part of ethnic minority and majority students. Sense of belonging only appeared to influence students’ study progress among the majority students.

The present study has several limitations. First, sense of belonging was measured with a six-item scale developed for the present study. The fact that we found no differences between ethnic minority and majority students’ sense of belonging (see Table 2), contrary to previous research (Hurtado 1994; Hurtado and Carter 1997; Johnson et al. 2007; Read et al. 2003; Zepke and Leach 2005), makes us wonder if the scale was appropriate. It is possible that the concept of sense of belonging is more complex than we assumed. Johnson et al. argue for example that sense of belonging as a theoretical construct has not been well studied and is inconsistently defined in the higher education literature. An interesting topic for future research might be to investigate the concept of sense of belonging further. A qualitative study can show the meaning of sense of belonging in the context of Dutch higher education. A second limitation concerns the relatively small number of ethnic minority participants from the different countries of origin. This made it impossible to examine the results of these different ethnic groups separately. It must therefore be kept in mind that the results as observed in the present study may not apply to each group in our study.

The present findings have several implications for future research on differences in study progress between ethnic minority and majority students. It is known that ethnic minority students make less study progress than majority students (Crul and Wolff 2002; Van den Berg 2002). However, the reason for this is still unknown. In our previous study (Severiens and Wolff 2008) we learned that peer and teacher interactions appear not to affect the study progress of ethnic minority students. The results of the present study add to this finding that ethnic minority students’ study progress appears not to be influenced by the activating character of the program or by the extent to which they feel they belong in the educational program. Therefore, it is still unclear what factors do directly affect the study progress of ethnic minority students. An interesting topic for future research would be to look more closely at the lives of different students. Are there differences between ethnic minority and majority students’ life domains and the extent to which these domains interrelate? It is, for example, imaginable that ethnic minority students have to spend more time working during their studies compared to majority students and that this results in a work-study conflict. This in turn might reduce study progress and ultimately lead to withdrawal from higher education.

The findings presented here have practical implications for higher education in the Netherlands. For both majority and minority students, activating learning environments contribute to their levels of peer and teacher interactions. For ethnic minority students, formal relationships seem to be crucial to their sense of belonging at the institution. It is up to the institutions to promote these formal relationships between students and teachers and among students. For majority students, informal relationships with peers are of considerable importance to their sense of belonging. Since their feeling of belonging influences their study progress, it is important to enable majority students to develop such informal relationships within the institution.

Notes

In our former work the term ‘integration’ was used. The present paper uses the same operationalization, but a different term (‘interaction’) in order to be more explicit about our specific interpretation of the Tinto concepts of integration.

Both the model for Western minority students as well as the model for non-Western minority students appeared to fit the data well. Subsequently, a multiple group analysis revealed that the magnitude and direction of the hypothesized relationships were invariant across both ethnic groups. Given these results, we concluded that the model generalizes across Western ethnic minority students and non-Western ethnic minority students. Therefore, the group of Western minority students and the group of non-Western minority students were joined together in a group of ethnic minority students (N = 145) in the present study.

References

Arbuckle, J. L., & Wothke, W. (1999). Amos 4.0 users guide. Chicago, IL: Smallwaters Corporation.

Beekhoven, S. (2002). A fair change of succeeding: Study careers in Dutch higher education. PhD thesis, SCO-Kohnstamm Instituut, Amsterdam.

Beekhoven, S., De Jong, U., & Van Hout, H. (2002). Explaining academic progress via combining concepts of integration theory and rational choice theory. Research in Higher Education, 43(5), 577–600.

Berger, J. B. (2000). Optimizing capital, social reproduction, and undergraduate persistence. A sociological perspective. In J. M. Braxton (Ed.), Reworking the student departure puzzle. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

Berger, J. B., & Milem, J. F. (1999). The role of student involvement and perceptions of integration in a causal model of student persistence. Research in Higher Education, 40(6), 641–664.

Braxton, J. M., Milem, J. F., & Sullivan, A. S. (2000). The influence of active learning on the student departure process: Toward a revision of Tinto’s theory. The Journal of Higher Education, 71(5), 569–590.

Cabrera, A. F., Castanada, M. B., Nora, A., & Hengstler, D. (1992). The convergence between two theories of college persistence. Journal of Higher Education, 63(2), 143–163.

Carmines, E. G., & McIver, J. (1981). Analyzing models with unobserved variables: Analysis of covariance structures. In E. F. Borgatta & G. W. Bohrnstedt (Eds.), Social measurement: Current issues. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Crul, M., & Wolff, R. (2002). Talent gewonnen. Talent verspild? Een kwantitatief onderzoek naar de instroom en doorstroom van allochtone studenten in het Nederlands Hoger Onderwijs 1997-2001 [Finding talent. Wasting talent?]. Utrecht: ECHO.

Eimers, M. T., & Pike, G. R. (1997). Minority and nonminority adjustment to college: Differences or similarities? Research in Higher Education, 38(1), 77–97.

Hobson-Horton, L. D., & Owens, L. (2004). From freshman to graduate: Recruiting and retaining minority students. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 3(1), 86–107.

Hoffman, M., Richmond, J., Morrow, J., & Salomone, K. (2003). Investigating ‘sense of belonging’ in first-year college students. Journal of college student Retention, 4, 227–256.

Hofman, W. H. A., & Van den Berg, M. N. (2003). Ethnic-specific achievements in Dutch higher education. Higher Education in Europe, 28(3), 371–389.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modelling, 6, 1–55.

Hurtado, S. (1994). The institutional climate for talented Latino students. Research in Higher Education, 35(1), 21–41.

Hurtado, S., & Carter, D. F. (1997). Effects of college transition and perceptions of the campus racial climate on Latino college students’ sense of belonging. Sociology of Education, 70(4), 324–345.

Jennissen, R. (2006). Allochtonen in het hoger onderwijs [Minorities in higher education]. DEMOS, 22(7), 65–68.

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R., & Smith, K. (1998). Active learning: Cooperation in the college classroom. Edina, MN: Interaction Book Company.

Johnson, D. R., Soldner, M., Brown Leonard, J., Alvarez, P., Kurotsuchi Inkelas, K., Rowan-Kenyon, H., et al. (2007). Examining sense of belonging among first year undergraduates from different racial/ethnic groups. Journal of College Student Development, 48(5), 525–542.

Just, H. D. (1999). Minority retention in predominantly white universities and colleges: The importance of creating a good ‘fit’. ERIC Report E 439 641, pp. 1–18.

MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 130–149.

Nora, A., & Cabrera, A. F. (1996). The role of perceptions of prejudice and discrimination on the adjustment of minority students to college. The Journal of Higher Education, 67(2), 119–148.

Pascarella, E. T., Duby, P. B., & Iverson, B. K. (1983). A test and reconceptualization of a theoretical model of college withdrawal in a commuter institution setting. Sociology of Education, 56(2), 88–100.

Prince, M. (2004). Does active learning work? A review of the research. Journal of engineering education, 93(3), 223–231.

Punnett, L., & Van der Beek, A. J. (2000). A comparison of approaches to modeling the relationship between ergonomic exposures and upper extremity disorders. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 37(6), 645–655.

Read, B., Archer, L., & Leathwood, C. (2003). Challenging cultures? Student conceptions of ‘belonging’ and ‘isolation’ at a post-1992 university. Studies in Higher Education, 28(3), 261–277.

Severiens, S. E., & Wolff, R. (2008). A comparison of ethnic minority and majority students: Social and academic integration and quality of learning. Studies in Higher Education, 33(3), 253–266.

Severiens, S. E., & Wolff, R. (2009). Study success of students from ethnic-minority backgrounds. An overview of explanations for differences in study success. In M. Tight, J. Huisman, K. H. Mok, & C. Morphew (Eds.), International handbook of higher education. London: Routledge.

Severiens, S. E., Ten Dam, G., & Blom, S. (2006). Comparison of Dutch ethnic minority and majority engineering students: Social and academic integration. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 10(1), 75–89.

Swail, W. S., Redd, K. E., & Perna, L. W. (2003). Retaining minority students in higher education: A framework for success. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report, 30(2), 1–187.

Thomas, L. (2002). Student retention in higher education: The role of institutional habitus. Journal of Educational Policy, 17(4), 423–442.

Tinto, V. (1975). Dropout from higher education: A theoretical synthesis of recent research. Review of Educational Research, 45(1), 89–125.

Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving college. Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition (2nd ed.). Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Tinto, V. (1997). Classrooms as communities: Exploring the educational character of student persistence. The Journal of Higher Education, 68(6), 599–623.

Tinto, V. (1998). Colleges as communities. Taking research on student persistence seriously. The Review of Higher Education, 21(2), 167–177.

Umbach, P. D., & Wawrzynski, M. R. (2005). Faculty do matter: The role of college faculty in student learning and engagement. Research in Higher Education, 46(2), 153–184.

Van den Berg, M. N. (2002). Studeren? (G)een punt! Een kwantitatieve studie naar studievoortgang in het Nederlands wetenschappelijk onderwijs in de periode 1996–2000 [A quantitative study on study progress in Dutch higher education in the period from 1996 to 2000]. Erasmus University Rotterdam, Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation.

Van den Berg, M. N., & Hofman, W. H. A. (2005). Student success in university education: A multi-measurement study of the impact of student and faculty factors on study progress. Higher Education, 50, 413–446.

Yorke, M., & Thomas, L. (2003). Improving the retention of students from lower socio-economic groups. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 25(1), 63–74.

Zea, M. C., Reisen, C. A., Beil, C., & Caplan, R. D. (1997). Predicting intention to remain in college among ethnic minority and nonminority students. The Journal of Social Psychology, 137(2), 149–160.

Zepke, N., & Leach, L. (2005). Integration and adaptation: Approaches to the student retention and achievement puzzle. Active Learning in Higher Education, 6(1), 46–59.

Zepke, N., Leach, L., & Prebble, T. (2006). Being learner centered: One way to improve student retention? Studies in Higher Education, 31(5), 587–600.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Meeuwisse, M., Severiens, S.E. & Born, M.P. Learning Environment, Interaction, Sense of Belonging and Study Success in Ethnically Diverse Student Groups. Res High Educ 51, 528–545 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-010-9168-1

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-010-9168-1