Abstract

Rabin (Econometrica 68(5):1281–1292, 2000) argues that, under expected-utility, observed risk aversion over modest stakes implies extremely high risk aversion over large stakes. Cox and Sadiraj (Games Econom. Behav. 56(1):45–60, 2006) have replied that this is a problem of expected-utility of wealth, but that expected-utility of income does not share that problem. We combine experimental data on moderate-scale risky choices with survey data on income to estimate coefficients of relative risk aversion using expected-utility of consumption. Assuming individuals cannot save implies an average coefficient of relative risk aversion of 1.92. Assuming they can decide between consuming today and saving for the future, a realistic assumption, implies quadruple-digit coefficients. This gives empirical evidence for narrow bracketing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This is true for concave differentiable utility functions.

Under asset integration utility is derived from final wealth rather than gains and losses.

It could also be the case that players view the experiments as detached from the rest of their lives. After the games one farmer stated he was going to go get drunk because his wife had no claim over his winnings. He explained that this was because the money did not come from his salary but his own “special winnings.”

In the data section we discuss the advantages of using income rather than wealth to derive consumption.

In 1991 the University of Wisconsin and the Centro Paraguayo de Estudios Sociológicos implemented a survey of 300 rural Paraguayan households in three departments and 16 villages across the country. The sample was random, and stratified by land-holdings. The original survey was followed up by subsequent rounds in 1994, 1999, and, the data we are using, 2002.

Thank you to Edi Grgeta for pointing out this interesting multiplier effect.

Although, if βR ≠ 0 then consumption will either go towards 0 or infinity over time.

Rather than considering a bet on the roll of the die, consider the simpler case of a bet on the toss of a coin. Imagine a player decides how much to bet, b, and has a 50/50 chance of winning the high amount hb or the low amount lb where h > 1 > l > 2 − h. From Eq. 3, the player’s maximization problem is

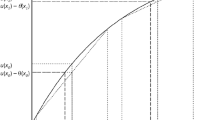

$$\max_b V=\frac{1}{2} K \left((h-1)b+\frac{y}{1-\frac{1}{R}}\right)^{1-\gamma} \frac{1}{1-\gamma} + \frac{1}{2} K \left((l-1)b+\frac{y}{1-\frac{1}{R}}\right)^{1-\gamma} \frac{1}{1-\gamma}.$$Solving the first order condition we find that \(b\,=\,\left(y\,/\,\left(1\,-\,\frac{1}{R}\right)\right)\left[(1\,-\,l)^{-\frac{1}{\gamma}} \,-\, (h-1)^{-\frac{1}{\gamma}}\right] \left/\phantom{\left[(1)^{\frac{\gamma}{\gamma}}\right]}\right.\) \( \left[(h-1)^{\frac{\gamma-1}{\gamma}} + (1-l)^{\frac{\gamma-1}{\gamma}}\right]\). Thus, as R →1 + we see b → ∞ and so, no matter the level of risk aversion, a player should choose to bet the maximal amount. If the player does not, he must be infinitely risk averse. We also calculate the first and second partial derivatives and find that for R > 1, \(\frac{\partial \gamma}{\partial R}<0\) and \(\frac{\partial^2 \gamma}{\partial R^2}>0\). This means that for a given bet size, the coefficient of relative risk aversion is increasing at an increasing rate as the interest rate decreases and approaches 1. In fact, as R goes to 1 from above, \(\frac{\partial \gamma}{\partial R}\) goes to − ∞.

Since this risk is decided once, this situation is much riskier than one in which the farmer has a 50% chance each day of having high or low income on that day.

References

Benartzi, Shlomo and Richard H. Thaler. (1995). “Myopic Loss Aversion and the Equity Premium Puzzle,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 110(1), 73–92.

Binswanger, Hans P. (1981). “Attitudes Toward Risk: Theoretical Implications of an Experiment in Rural India,” The Economic Journal 91(364), 867–890.

Cardenas, Juan Camilo and Jeffrey P. Carpenter. (2007). “Behavioral Development Economics: Lessons from Field Labs in Developing Countries,” Journal of Development Studies (in press).

Cohen, Alma and Liran Einav. (June 2007). “Estimating Risk Preferences from Deductible Choice,” American Economic Review 97(3), 745–788.

Cox, James C. and Vjollca Sadiraj. (2006). “Small- and Large-Stakes Risk Aversion: Implications of Concavity Calibration for Decision Theory,” Games and Economic Behavior 56(1), 45–60.

Donkers, Bas, Bertrand Melenberg, and Arthur van Soest. (2001). “Estimating Risk Attitudes using Lotteries: A Large Sample Approach,” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 22(1), 165–195.

Fudenberg, Drew and David K. Levine. (2006). “A Dual-Self Model of Impulse Control,” American Economic Review 96(5), 1449–1476.

Gertner, Robert. (1993). “Game Shows and Economic Behavior: Risk-Taking on ‘Card Sharks’, ” Quarterly Journal of Economics 108(2), 507–521.

Gollier, Christian and John W. Pratt. (1996). “Risk Vulnerability and the Tempering Effect of Background Risk,” Econometrica 64(5), 1109–1123.

Holt, Charles A. and Susan K. Laury. (2002). “Risk Aversion and Incentive Effects,” American Economic Review 92(5), 1644–1655.

Kahneman, Daniel and Dan Lovallo. (1993). “Timid Choices and Bold Forecasts: A Cognitive Perspective on Risk Taking,” Management Science 39(1), 17–31.

Köszegi, Botond and Matthew Rabin. (2006). “A Model of Reference-Dependent Preferences,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 121(4), 1133–1165.

Mas-Colell, Andreu, Michael D. Whinston, and Jerry R. Green. (1995). Microeconomic Theory. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mehra, Rajnish and Edward C. Prescott. (1985). “The Equity Premium: A Puzzle,” Journal of Monetary Economics 15(2), 145–161.

Menezes, Carmen F. and D.L. Hanson. (1970). “On the Theory of Risk Aversion,” International Economic Review 11(3), 481–487.

Meyer, Donald J. and Jack Meyer. (2005). “Relative Risk Aversion: What Do We Know?” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 31(3), 243–262.

Nicholson, Walter. (2002). Microeconomic Theory. Thomson Learning Inc.

Palacios-Huerta, Ignacio and Roberto Serrano. (2006). “Rejecting Small Gambles under Expected Utility,” Economics Letters 91(2), 250–259.

Rabin, Matthew. (2000). “Risk Aversion and Expected-utility Theory: A Calibration Theorem,” Econometrica 68(5), 1281–1292.

Rabin, Matthew and Richard H. Thaler. (2001). “Anomalies: Risk Aversion,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 15(1), 219–232.

Read, Daniel, George Loewenstein, and Matthew Rabin. (1999). “Choice Bracketing,” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 19(1), 171–197.

Rubinstein, Ariel. (2001). “Comments on the Risk and Time Preferences in Economics.” Unpublished Manuscript.

Schechter, Laura. (2007). “Traditional Trust Measurement and the Risk Confound: An Experiment in Rural Paraguay,” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 62(2), 272–292.

Varian, Hal R. (1992). Microeconomic Analysis. New York: Norton.

Watt, Richard. (2002). “Defending Expected Utility Theory: Comment,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 16(2), 227–230.

Zeckhauser, Richard and Emmett Keeler. (1970). “Another Type of Risk Aversion,” Econometrica 38(5), 661–665.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The author received funding from SSRC, RSF, Berkeley IBER, Berkeley CIDER, and the Giannini Foundation. I am grateful to José Molinas and Instituto Desarrollo for their support in Paraguay and thank Ethan Ligon, Bill Provencher, Matthew Rabin, an anonymous referee, and seminar participants at the 2006 ESA meetings for their comments. I also wholeheartedly thank Edi Grgeta and Larry Karp for finding mistakes in an earlier draft.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schechter, L. Risk aversion and expected-utility theory: A calibration exercise. J Risk Uncertainty 35, 67–76 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-007-9017-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-007-9017-6