Abstract

Recent material developments of fast solid oxide and lithium ion conductors are reviewed. Special emphasis is placed on the correlation between the composition, structure, and electrical transport properties of perovskite-type, perovskite-related, and other inorganic crystalline materials in terms of the required functional properties for practical applications, such as fuel or hydrolysis cells and batteries. The discussed materials include Sr- and Mg-doped LaGaO3, Ba2In2O5, Bi4V2O11, RE-doped CeO2, (Li,La,)TiO3, Li3La3La3Nb2O12 (M=Nb, Ta), and Na super-ionic conductor-type phosphate. Critical problems with regard to the development of practically useful devices are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

After Walter Nernst’s pioneering discovery [1] of various solid ceramic oxides being “conductors of second kind,” as electrolytes were called at the time of this discovery at the end of the 19th century, fast ionic transport in solids was observed for a variety of metal halides and sulfides during the early decades of the 20th century. However, fast progress in understanding and developing novel materials for practical applications has only been achieved during the last few decades. From this point of view, solid electrolytes should have high ionic conductivity based on a single predominantly conducting anion or cation species and should have negligibly small electronic conductivity. Typically, useful solid electrolytes exhibit ionic conductivities in the range of 10−1–10−5 S/cm at room temperature. This value is in-between that of metals and insulators and has the same order of magnitude as those of semiconductors and liquid electrolytes (Fig. 1) [2–6].

Research on solid electrolytes has recently drawn much attention due to the wide range of potential important technological applications in solid-state devices, including solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs), proton exchange membrane fuel cells, water hydrolysis cells, chemical sensors (e.g., for H2, O2, NH3, CO, CO2, NO x , SO x , CH4, CnH2n+2, SO x , etc.), high-energy-density rechargeable (secondary) batteries, electrochromic displays, chemotronic elements (e.g., nonvolatile memory elements) thermoelectric converters, and photogalvanic solar cells [7–25]. Furthermore, solid electrolytes turned out to be very useful for the determination of fundamental thermodynamic quantities, such as Gibbs energies, entropies, enthalpies, activity coefficients, and nonstoichiometries of solids at elevated temperatures and kinetic parameters, such as chemical diffusion coefficients, diffusivities, and Wagner factors, as functions of the stoichiometry and temperature [16].

A broad variety of materials is known today to exhibit ionic conduction, including single-crystalline, polycrystalline, and amorphous ceramic materials, composites, and polymer salt mixtures. Especially, several solid electrolytes are known for monovalent protons and lithium, sodium, silver, potassium, copper, and fluoride ions, as well as divalent oxide and metal ions [1–6]. Among those types of ions, protons, oxide and lithium ions play a key role for future technologies. Recent progress in the development of new materials, especially compounds based on perovskite and related structures are discussed in this review.

Oxide ion electrolytes

General considerations

Doping parent metal oxides with oxides of lower-valent cations than the host cation produces anion deficiencies, i.e., oxygen stoichiometries less than that of the mother phase. This is an essential requirement for oxide ion conduction [2, 26, 27], because the transport of oxide ions occurs generally by a hopping process between an occupied and a vacant oxide ion site. It is generally accepted that high ionic conduction of oxides is based on the following structural properties:

-

1.

An optimum number of oxide ion vacancies which should be structurally distributed

-

2.

Vacant and occupied sites should have nearly the same potential energies for low-activation-energy conduction processes

-

3.

Weak frame-work and 3D structures

-

4.

Weak covalent bonding between the metal and oxygen (M–O)

-

5.

Host and guest metal ions should be stable with different coordination numbers of oxygen.

Solid oxide ion electrolytes are notably of interest for energy conversion and environmental applications, including SOFCs, oxygen sensors, oxygen pumps, and oxygen permeable membranes [9–14, 17, 23–25]. Besides solid electrolytes, suitable predominantly electronically (mixed ionic–electronic) conducting anode and cathode materials have to be developed. Present SOFCs are based on fluorite-type Y2O3-doped ZrO2 (YSZ), perovskite-type, Sr-doped LaMnO3 (LSM) cathodes and composite Ni-YSZ cermet anodes [9–14, 17]. A critical problem is the high operating temperature (≈1,000 °C) that is required for reasonably high oxide ion conduction of YSZ. The high operating temperature leads to several materials problems [25]. These are:

-

1.

Interfacial diffusion of Sr and La between the electrode (LSM) and the electrolyte, leading to the formation of poor conducting reaction products, e.g., SrZrO3 and La2Zr2O7

-

2.

Mechanical stress due to different thermal expansion coefficients, which destroys good electrical electrolyte and electrode contacts

-

3.

High cost of the bipolar separators, which are required for long-term mechanical and chemical stability in oxidizing and reducing atmospheres

-

4.

Lack of appropriate sealing materials that are chemically inert against chemical reactions with all components of the fuel cell.

Accordingly, there is strong, currently ongoing research for intermediate temperature (IT; 400–800 °C) solid oxide conductors. In this regard, a set of functional material properties has to be fulfilled for practical SOFC development:

-

1.

High oxide ion conductivity at the operating temperatures (400–800 °C) without structural phase transition and decomposition

-

2.

Electrochemical stability up to at least 1.2 V against air or pure O2 at the operating temperature

-

3.

Negligible electronic conductivity over the entire or most of the employed range of oxygen partial pressures and temperature

-

4.

Dense, gas-tight, pore-free preparation of the material with good adhesion to both anode and cathode materials, with matching thermal expansion coefficients (including the sealing material)

-

5.

Stability against chemical reactions with anode, cathode, and sealing materials over an extended period of operation time

-

6.

Negligible electrolyte–electrode interface and charge-transfer resistances

-

7.

Low-cost, nontoxicity, easiness of preparation, chemical and kinetic stability under ambient conditions, especially conditions of moisture and CO2 content in the atmosphere.

Various transition inorganic metal oxides possessing fluorite, pyrochlore, perovskite, and structurally perovskite-related brownmillerite, Aurivillius, and Ruddlesden–Popper layered perovskites (e.g., K2NiF4-type) have been considered for the development of intermediate temperature solid oxide fuel cell (IT-SOFC) electrolytes. Table 1 lists the potential oxide electrolytes and comments on their technological problems with regard to their application in fuel cells [9–14, 17–25]. Figure 2 shows the Arrhenius plots for the oxide ion conductivities of selected metal oxides [13].

Arrhenius plot of the oxide ion conductivity of selected metal oxides in ambient atmosphere [13]

Oxide ion electrolytes based on ABO3 perovskite

Takahashi and Iwahara were the first to work on oxide ion conductors based on the perovskite structure ABO3 (A = Ca, Sr, La; B = Al, Ti) with aliovalent substitution of the metals [21]. The idealized crystal structures of perovskite and related structures are shown in Fig. 3. Only in recent years, perovskite and related crystal structures have been investigated more intensively with regard to the possibility of oxide ion conduction. Figure 4 summarizes the electrical conductivities of perovskite and structurally related materials. Partial substitution of Ca2+ by Nd3+ and Ga3+ by Al3+ in the perovskite-type NdAlO3 yields an anion-deficient compound with the chemical formula of \({\text{Nd}}_{{0.9}} {\text{Ca}}_{{0.1}} {\text{Al}}_{{0.5}} {\text{Ga}}_{{0.5}} {\text{O}}_{{3 - \delta }}\)which shows oxide ion conductivity of ≈10−2 S/cm at 700 °C [28]. Al3+-doped ABO3 (A = Na, K; B = Nb, Ta) exhibits ionic conductivity of ∼10−2 S/cm at 900 °C [29]. The highest bulk oxide ion conductivity value of 0.17 S/cm at 800 °C was observed for x = 0.2 and y = 0.17 in \({\text{La}}_{{1 - x}} {\text{Sr}}_{x} {\text{Ga}}_{{1 - y}} {\text{Mg}}_{y} {\text{O}}_{{3 - \delta }}\) (LSGM) [30–33], which is about four times higher than the conductivity of YSZ (3.6×10−2 S/cm at 800 °C). Accordingly, LSGM-based materials are presently considered as potential candidates for IT-SOFCs.

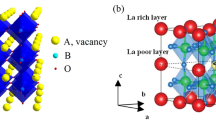

Idealized crystal structures of a perovskite (e.g., SrTiO3: Sr—open circles; TiO6—octahedra), b layered perovskite-type (e.g., Sr2TiO4: Sr—open circles; TiO6—octahedra), c Aurivillius (e.g., Bi2WO6: Bi2O2—tetrahedra; WO6—octahedra) and d brownmillerite (e.g., Ba2In2O5: Ba—open circles, InO6—octahedra; InO4—tetrahedra)

Arrhenius plots of oxide ion conductivities of selected perovskite and perovskite-related metal oxides as reported in the literature [14 and references therein]: 1 NaNb0.5Al0.5O2.5, 2 KNb0.5Al0.5O2.5, 3 Ba2NaMoO5.5, 4 Ba2LiMoO5.5, 5 Ba2NaWO5.5, 6 \({\text{CaTi}}_{{0.95}} {\text{Mg}}_{{0.05}} {\text{O}}_{{3 - \delta }}\), 7 \({\text{Nd}}_{{0.9}} {\text{Ca}}_{{0.1}} {\text{AlO}}_{{3 - \delta }}\), 8 La0.9Sr0.1Ga0.8Mg0.2O2.85, 9 Ba2In2O5, 10 Ba3In2ZrO8, 11 Bi4V2O11, 12 \({\text{Bi}}_{4} {\text{V}}_{{1.8}} {\text{Cu}}_{{0.2}} {\text{O}}_{{11 - \delta }}\), and 13 La0.8Sr0.2Ga0.83Mg0.17O2.815

Effect of doping on the ionic conductivity of LSGM perovskites

Effect of A-site substitution

Figure 5 shows the chemistry of metal ion substitution in the case of perovskite-type LSGM. Partial substitution (10 mol %) of La by other rare earth ions at the A-site (Nd, Sm, Gd, Y, Yb) in La0.9Sr0.1Ga0.8Mg0.2O2.85 (LSGM) decreases the total electrical conductivity [34]. Unlike other rare earth substitutions of LSGM, Pr substitution (50 at. %) of La does not affect the electrical conductivity, except with a slight decrease at high temperature, while the conductivity corresponds to that of LSGM at low temperature [35]. Among the alkaline earth ions occupying the A-site, Sr provides the highest ionic conductivity enhancement, compared to Ca and Ba. K and Pr substitutions for La/Sr in LSGM result in a simple cubic perovskite structure. Replacement of Sr by K in La0.9Sr0.1Ga0.8Mg0.2O2.85 (LSGM) shows a lower electrical conductivity (8.56×10−3 S/cm at 700 °C) with high activation energy of 1.42 eV, compared to 1.07 eV for LSGM.

Effect of B-site substitution

Partial substitution of Ga by Al or In in LSGM decreases the electrical conductivity. The decrease in electrical conductivity may be attributed to the changes in the crystal structure and lattice parameter. The complete replacement of trivalent Ga3+ by other isovalent metal ions such as Al3+, In3+, and Sc3+ in LSGM decreases the total ionic conductivity [36]. Oxygen-partial-pressure-dependent electrical measurements of La0.9Sr0.1In0.8Mg0.2O2.85 (LSIM) show p-type electronic conduction at high oxygen partial pressures in the range 10−6–0.21 atm at 750 °C, with a slope of about 1/6 of \({\text{dln}}\sigma {\text{/dln}}_{{{\text{PO}}_{{\text{2}}} }} \). This behavior may be attributed to the following defect reaction [35]:

where O o, \(V^{{ \bullet \bullet }}_{{\text{o}}}\) and \(h^{ \bullet }\) represent regular lattice oxide ions, oxide ion vacancies, and electronic holes, respectively. It may be noted that the electrical conductivity of LSIM does not vary significantly with the oxygen partial pressure in the regime 10−5–10−22 atm, indicating prevailing ionic conductivity. Similar p-type electronic conduction has been observed for other In- and Pr-doped LSGM and LSIM materials. The replacement of divalent Mg2+ in LSGM by transition metals such as V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, and Ni exhibits mixed oxide ion and electronic conduction [37] in air, which is due to the mixed valence of the dopant metal ions. A small amount of Co substitution for Mg in LSGM, providing the composition La0.9Sr0.1Ga0.8Mg0.15Co0.05O2.85, exhibits slightly higher ionic conductivity compared to LSGM [38]. Substitution of In for Ga and Pr for La, forming metal oxides of the composition of La0.4Pr0.4Sr0.2In0.8Mg0.2O2.8, exhibits an electrical conductivity of 3.2×10−5 S/cm at 200 °C in air, with an activation energy of 0.44 eV. The increase in the electrical conductivity may be due to the higher number of oxygen vacancies or an increase in the electronic conductivity due to mixed-valent Pr [35].

Chemical compatibility of LSGM with potential SOFC electrodes

A substantial amount of work has been dedicated to the understanding of the chemical compatibility of LSGM with conventional SOFC electrodes, e.g., Sr-doped LnBO3 (Ln = rare earths, B = Mn, Co) and Ni cermet, in fuel cells under operating conditions. Based on powder X-ray diffraction studies, it has been concluded that the LSGM electrolyte appears to be sufficiently stable against a chemical reaction with perovskite-like LSM and Sr-doped SmCoO3 [39]. Furthermore, the average thermal expansion coefficient of LSM perovskite (11.1×10−6 °C−1) is very close to that of LSGM (11.5×10−6 °C−1) in the temperature range 25–1,200 °C.

A few studies have shown that LSGM reacts upon exposure to CO and CO2 atmospheres due to the formation of alkaline carbonates, and the Ga suboxides have a high volatilization rate in reducing atmospheres (e.g., in H2 and the H2O or CO2 mixtures) [40]. Furthermore, LSGM reacts with potential Ni anodes and forms reaction products (LaSrGaO4 and LaSrGa3O7) at the anode–electrolyte interface. Accordingly, complete replacement of the costly and less-stable Ga with other suitable metal ions without affecting the electrical properties of LSGM and the identification of Ga-free perovskite-type or perovskite-related electrolytes for IT-SOFC and other applications is still a major challenge.

Perovskite-type compounds without La and Ga for oxide ion conduction

Thangadurai and Weppner have investigated the electrical transport properties of metal oxides that also possess perovskite-type structures, but do not contain trivalent La and Ga. For example, SrSn1−x Fe x O3−δ (0<x<1) perovskite-type oxides have been prepared by solid-state reactions and characterized by impedance methods [41, 42]. Hashimoto et al. reported high oxide ion conduction in Ga- and Sc-doped CaTiO3. Among the investigated compounds, CaTi0.9Sc0.1O3−x showed predominantly ionic conduction over a wide range of oxygen partial pressures at 800 °C, while the Ga- and Al-doped samples exhibited p- and n-type electronic conduction at high and low oxygen partial pressures, respectively [43]. Impedance (5 Hz–13 MHz) studies showed that \({\text{SrFe}}_{{0.1}} {\text{Sn}}_{{0.1}} {\text{O}}_{{3 - \delta }}\) exhibits two semicircles (which may be attributed to bulk and grain boundary contributions), while samples with higher Fe-contents show only a single semicircle or part of a semicircle [41, 42]. The absence of a low-frequency tail indicates that the electrolyte–electrode interfaces were not blocking. Accordingly, the low-frequency intercept may correspond to electronic conductivity.

Very interestingly, in contrast to previous investigations, it has been found that solid solutions SrSn1−x Fe x O3 containing low Fe contents (<0.3) exhibit regimes of predominant ionic and electronic conductivity. At high and low oxygen partial pressures, for example, SrSn0.9Fe0.1O3 exhibits p- and n-type electronic conductivity with a slope of ±1/4, respectively. This behavior is assumably due to the following defect reactions [41, 42] (Fig. 6):

at high and low oxygen partial pressures, respectively, assuming a high, practically constant oxygen vacancy concentration, where e′ represents excess electrons in the crystals. The open circuit voltages at 750 °C employing the x = 0.1, 0.15, and 0.2 members of \({\hbox{SrSn}}_{{1 - x}} {\hbox{Fe}}_{x} {\hbox{O}}_{{3 - \delta }}\) in air-hydrogen galvanic concentration cells were found to be 460, 268, and 170 mV, respectively, which proves the existence of a predominantly ionically conducting regime within the employed oxygen partial pressure range, as concluded from Nernst’s equation. These highly electronically conducting materials may find application as electrodes for SOFCs and sensors.

Oxide ion conductors based on the Brownmillerite structure

Brownmillerite structured compounds have the general chemical formula A2B2O5. The structure is closely related to that of the perovskites, but differs by the oxygen vacancy distribution (Fig. 3d). A well-known oxide ion conductor of this structural family is Ba2In2O5, discovered by Goodenough et al. in 1990 [44]. Ba2In2O5 shows fast oxide ion conduction above an order–disorder transition at 930 °C, when the structure changes to that of a perovskite, with disordered oxygen vacancies. Chemical substitution has been employed not only to suppress the anion-vacancy ordering, but also to improve the ionic conductivity. Substitution of tetravalent Zr4+, Hf4+, or Ce4+ for In3+ in Ba2In2O5 suppresses the phase-transition and provides high ionic conductivity at 400 °C. The ionic transport in these intergrowth structured materials at low temperature is obviously due to the disordered arrangement of oxygen vacancies [44–46].

Substitution of In by Ga in Ba2In2O5 was found to decrease the ionic conductivity, especially at high temperature, which may be due to the replacement of the weak In–O bond by the strong Ga–O bond, which increases the electrostatic attraction between the metal and oxide ions [47]. Also, recent studies have shown that Ba2In2O5 exhibits proton conduction in hydrogen-containing atmospheres (e.g., water vapor) [48–50]. The existence of proton conductivity can be explained using the following defect equilibrium reaction:

Practical applications of Ba2In2O5 and its derived compounds in fuel cells and other ionic devices may be limited due to their degradation in CO2 atmospheres with the formation of barium carbonate [12–14] and the limited stability of In3+ in reduced atmospheres that leads to n-type electronic conduction at elevated temperatures.

Oxide ion conductors based on Aurivillius structure

In 1988, Abraham et al. reported high ionic conductivity in the Aurivillius phase (perovskite-related layered structure) with the chemical formula Bi4V2O11 [51], which is derived from Bi2WO6 (Fig. 2). Bi4V2O11 exhibits two reversible phase transitions at 450 °C (α→β) and 570 °C (β→γ). The low-temperature α-Bi4V2O11 crystallizes in a monoclinic cell and the anion vacancies are ordered in the perovkite-like layers, which are sandwiched between the {Bi2O2} layers. The α-phase shows low ionic conductivity of below 10−7 S/cm at 100 °C, which is attributed to the ordered oxygen ion vacancies. The high-temperature γ-Bi4V2O11 exhibits fast ionic conductivity of about 0.1 S/cm at 600 °C (0.23 eV), where the oxygen vacancies are disordered [46]. Attempts have been made to stabilize the γ-phase at room temperature by substituting aliovalent cations, such as Cu, Ti, Nb, etc., for vanadium in Bi4V2O11. Such stabilized compounds of the composition Bi2V2−x M x O11−y (M=Cr, Cu, Ti, Zr, Sn, Nb, Sb, Nb, Ta, Mo) exhibit a remarkably high oxide ion conduction at low temperature (<400 °C). For example, Bi4V1.8Cu0.2O10.7 exhibits a conductivity of 10−3 S/cm at 250 °C, which is about two orders of magnitude higher than that of the pure Bi4V2O11 at the same temperature [45].

Zur Loye et al. prepared novel series of n = 3 and 4 members of Aurivillius phases with the chemical formulas of Bi2Sr2M2′M″O11.5 (M′ = Nb, Ta; M″ = Al, Ga) and BaBi4Ti3MO14.5 (M = Sc, In, Ga), respectively. Among the investigated samples, the n = 4 member with the composition BaBi4Ti3InO14.5 exhibits an ionic conductivity of 10−2 S/cm at 900 °C, which is comparable to that of YSZ [52]. The practical application of the Aurivillius phases is restricted due to the low chemical stability of Bi, V, In, and Ti under low oxygen partial pressures at elevated temperatures, and also due to structural phase transitions which are associated with large-volume changes and degradation in CO2 atmospheres (Table 1). However, composite materials employing compounds with the same chemical composition find application as negative electrodes in SOFCs that utilize doped CeO2 as electrolyte. Shuk et al. recently reviewed the electrical transport properties of Bi-containing oxide-ion-conducting electrolytes [53].

Oxide ion electrolytes based on rare-earth-doped CeO2

At present, rare earth Gd- or Sm-doped CeO2 solid electrolytes are considered to be potential electrolytes for IT-SOFC applications because of their higher oxide ion conductivities compared to both Y-doped ZrO2 (YSZ) and Sr- and Mg-doped LaGaO3 (LSGM) in air [54–56] (Fig. 2) [13]. However, doped CeO2 shows n-type electronic conduction at temperatures above 700 °C at low oxygen partial pressures, but becomes predominantly ionically conducting in the temperature range 400–600 °C under oxygen partial pressures of 1–10−19 atm. This is sufficient to employ this compound as electrolyte in SOFCs. For example, Ce0.8Sm0.2O1.9 and Ce0.8Gd0.2O1.9 are used as electrolytes for IT-SOFCs using hydrocarbons as fuel and air as oxidant in the temperature range 400–550 °C. The low operation temperature (<600 °C) has many advantages over the presently most-employed high temperature (∼1,000 °C), such as flexibility in the choice of the electrodes, bipolar plates, and sealing materials, as well as long lifetimes of the devices.

Kharton et al. [57] and Inaba and Tagawa [58] reviewed the recent developments on ceria-based electrolytes and discussed their electrical transport properties, as well as their electrochemical performances. Among the various substitutions for Ce, Gd was found to be the optimum with regard to high ionic conductivity, which is presumably due to the matching of the ionic radii of Ce and Gd.

Solid-state lithium ion conductors (SSLICs)

General considerations

At present, lithium ion secondary battery developments are mainly based on LiCoO2 as positive electrode, lithium-ion-conducting organic polymer as electrolyte (LiPF6 dissolved in polyethylene oxide), and Li-metal or graphite as negative electrode [59, 60]. The formation of a solid electrolyte interface at the anode leads to a large irreversible capacity loss during the discharge cycles [61]. A further major concern is the safety aspect of liquid and common polymeric electrolytes. Liquid-free batteries that utilize solid state lithium ion conductors (SSLICs) are expected to show major advantages over the currently commercialized polymer/gel batteries. These include thermal stability, absence of leakage and pollution, high resistance to shocks and vibrations, and a large electrochemical stability window for practical applications.

Required functional properties of SSLICs for application in high-energy-density batteries

Potential SSLICs should show the following features for application in lithium batteries and other electrochemical devices:

-

(a)

High lithium ion conductivity at operating temperature (preferably at room temperature)

-

(b)

Negligible electronic conductivity over the entire employed range of lithium activity and temperature

-

(c)

Negligibly small or nonexistent grain-boundary resistance

-

(d)

Stability against chemical reaction with both electrodes, especially with elemental Li or Li-alloy negative electrodes during the preparation and operation of the cell

-

(e)

Matching thermal expansion coefficients of the electrolyte with both electrodes

-

(f)

High electrochemical decomposition voltage (>5.5 V vs Li)

-

(g)

Environmental benignity, nonhygroscopicity, low cost, and easiness of preparation.

So far, all discovered inorganic compounds had either high ionic conductivity or high electrochemical stability, but not both. Looking at the structure, the solid lithium ion conductors reported in the literature so far are 2D layered compounds, e.g., Li3N and Li-β-alumina, and 3D materials, e.g., Li14ZnGe4O16, (Li,La)TiO3 (LLT), Li1.3Ti1.7Al0.3(PO4)3, and xLi2O:yP2O5:zPON (LiPON, PON=phosphorous oxynitride) (Fig. 3) [62–66]. Table 2 shows the electrical conductivity properties of potential SSLICs and their technological problems in galvanic cell applications [67 and references therein].

Perovskite-type lithium ion conductors

To date, the highest bulk lithium-ion-conducting solid electrolytes are the perovskite (ABO3)-type lithium lanthanum titanate (LLT) Li3x La(2/3)−x □(1/3)−2x TiO3 (0<x<0.16) and structurally related materials (Fig. 7). Figure 8 shows the bulk lithium ion conductivity of selected SSLICs. Among them, the x≈0.1 member of LLT exhibits the highest bulk lithium ion conductivity of 10−3 S/cm at room temperature with an activation energy of 0.40 eV [68, 69]. Stramare et al. recently reviewed the lithium ion transport properties of LLT and structurally related materials [70].

The salient electrical and structural features of LLT perovskites are:

-

1.

The high lithium-ion-conducting phase has an A-site deficient perovskite-type structure. Lithium ion conduction occurs due to the motion of lithium ions along A-site vacancies. The window of four oxygen-separating adjacent A-sites constitutes the bottleneck for lithium ion migration. It is considered that BO6/TiO6 octahedra tilting facilitates the lithium ion mobility in the perovskite structure

-

2.

Cubic structures exhibit slightly higher conductivities than ordered tetragonal phases with the same bulk composition. The low ionic conductivity in the ordered phase is due to the unequal ordering of Li, La, and vacancies along the c-axis

-

3.

The ionic conductivity is highly sensitive to the lithium content, and a dome-shaped dependence of the conductivity on the Li content was found (Fig. 9) [70]. LLT substitution of 5 mol % Sr for La exhibits a slightly higher conductivity (1.5×10−3 S/cm at 27 °C) than the pure LLT, while complete substitution of other transition metal ions for Ti decreases the ionic conductivity (Fig. 10) [70]

-

4.

The optimum total lithium and vacancy concentration for high ionic conductivity was found to be in the range 0.44–0.45

-

5.

NMR studies reveal that at low temperature ( > room temperature), the lithium ion hops between cages through the bottleneck in the ab plane, and at high temperature the lithium ions hop in three directions

-

6.

The application of LLT as lithium ion electrolyte is not favorable because the compound is not stable in direct contact with elemental lithium and rapidly undergoes Li-insertion with consequent reduction of Ti4+ to Ti3+, leading to high electronic conductivity. Furthermore, LLT has been investigated with regard to its stability against lithium and intercalation of lithium using several electrochemical methods that include galvanostatic insertion, coulometric titration, and discharge/charge characteristics. The use of LLT as lithium battery electrode is limited because of the small lithium uptake and rather small practical capacity [69].

Variation of the lithium ion conductivity at room temperature for Li3x La(2/3)−x□(1/3)−2x TiO3 as a function of the lithium concentration [70]

Arrhenius plots of the electrical conductivities of a Li0.34La0.51TiO2.94, b Li0.31La0.63Ti0.9Co0.1O3 (□), c Li0.31La0.63Ti0.9Ni0.1O3 (○), d Li0.1La0.63Mg0.5W0.5O3, e Li0.34Nd0.55TiO3 (•), f Li0.1La0.3NbO3, g Li0.25La0.25TaO3 ( ), h Li0.3Sr0.6Nb0.5Ti0.5O3 (△), i Li0.3Sr0.6Ta0.5Ti0.5O3 (●), and j Li0.5Sr0.5Fe0.25Ta0.75O3 [70]

), h Li0.3Sr0.6Nb0.5Ti0.5O3 (△), i Li0.3Sr0.6Ta0.5Ti0.5O3 (●), and j Li0.5Sr0.5Fe0.25Ta0.75O3 [70]

Na super-ionic conductor (NASICON) structured lithium ion electrolytes

The highest lithium ion conductivity of Na super-ionic conductor (NASICON)-type phosphates has been obtained with an optimum cell volume of 1,310 Å3 (Fig. 11) [71, 72]. For example, among the LiMIV 2(PO4)3 (MIV=Ti, Zr, Ge, Hf) NASICONs, the Ti-compound exhibits high lithium ion conductivity of about 10−5 S/cm at 25 °C, which is presumably attributed to the lowest cell volume of LiTi2(PO4)3. The lithium ion conductivity has been further improved by Al3+ ion substitution for Ti4+ in Li1+x Ti2−x Al x (PO4)3. It has been discussed that this substitution decreases the porosity and increases the bulk conductivity. It should be mentioned that trivalent Al has a lower ionic radius (0.53 Å) than tetravalent Ti with an octahedral coordination (0.60 Å). Therefore, the increase in ionic conductivity cannot be explained on the basis of cell volume considerations. The effect is easily understood using the Gibbs energy of formation values of Al2O3 and TiO2 [64]. Accordingly, substitution of the more stable Al3+ for the less stable parent Ti4+ is expected to increase the M–O bond strength and to decrease the Li–O bond strength, which results in an increase in the lithium ion conductivity of LiTi2(PO4). Similarly, the increase in lithium ion conductivity of LiZr2(PO4)3 by substitution of Zr with Ta also follows the same Gibbs energy consideration, because Ta5+ (0.64 Å) has a smaller ionic radius than Zr4+ (0.72 Å) at the octahedral coordination [73].

Garnet structure related fast lithium ion conductors

Thangadurai and Weppner were the first to explore novel garnet-type lithium containing transition metal oxides [67, 74–80] with the nominal chemical compositions Li5La3M2O12 (M = Nb, Ta) and Li6ALa2M2O12 (A = Ca, Sr, Ba; M = Nb, Ta) for fast lithium ion conduction. Among the materials investigated, Li6BaLa2Ta2O12 exhibits the highest lithium ion conductivity of 4×10−5 S/cm at 22 °C with an activation energy of 0.40 eV [78], which is comparable to those of other fast lithium ion conductors, especially the presently employed thin-film solid electrolyte lithium phosphorus oxynitride (LiPON) (σ = 3.3×10−6 S/cm at 25 °C; E a=0.54 eV) for all-solid-state lithium batteries [62].

In Fig. 12, we compare the total (bulk+grain-boundary) electrical conductivity of Li6BaLa2Ta2O12 with the conductivities of fast lithium conductors that are stable against chemical reaction with elemental Li [69]. It should be mentioned that the total and bulk conductivities are nearly identical for the presently investigated garnet-type materials. For example, Li6SrLa2Ta2O12 and Li6BaLa2Ta2O12 compounds exhibit bulk ionic conductivities of 8.9×10−6 and 5.4×10−5 S/cm, respectively, at 22 °C [78]. This finding is the most attractive feature of the investigated garnet-type oxides compared to other ceramic lithium ion conductors. For comparison, the best lithium ion conductor based on perovskite LLT exhibits a total conductivity that is about two orders of magnitude lower than the bulk conductivity [68–70]. Furthermore, impedance and DC electrical investigations confirm the absence of electrolyte–electrode interface resistances in the case of Li6ALa2Ta2O12 (A=Sr, Ba) when lithium metal is employed as reversible electrode (Fig. 13). Also, DC electrical measurements reveal that the electronic conductivity is much smaller and the compounds exhibit high electrochemical stability of about 6 V against metallic lithium at room temperature [78]. Bond valence models consistently suggest that the Li+ ion transport pathways in Li5La3M2O12 directly connect the almost fully occupied octahedral sites [80]. Thus, a vacancy-type ion transport is expected to be the dominant contribution to the long-range ion transport, while the tetrahedrally coordinated “interstitial sites” mainly act as sources or sinks of the mobile ions.

Comparison of the lithium ion conductivity of garnet-type Li6BaLa2Ta2O12 with other SSLICs, which are stable against reaction with lithium [78]

AC impedance plots of Li6BaLa2Ta2O12 obtained using lithium ion blocking Au electrodes (top) and lithium ion reversible elemental Li electrodes (bottom) a Li6SrLa2Ta2O12; b Li6BaLa2Ta2O12 [78]

The chemical compatibility between Li6BaLa2Ta2O12 and lithium battery positive electrodes [LiCoO2, LiMn2O4, LiNiO2 and Li2MMn3O8 (M = Fe, Co)] shows that Li6BaLa2Ta2O12 is chemically stable against reaction with 2D layered structured LiCoO2 up to 900 °C, while other transition metal Mn-, Ni-, (Fe,Mn-), and (Co,Mn)-based cathodes were found to react and form perovskite-like structure reaction products at temperatures above 400 °C [79].

Conclusions and outlook

Among the various inorganic structural families, the perovskite-type (ABO3) and its structurally related materials form one of the most important and fascinating classes of materials with interesting oxide ion conductivity properties. The high oxide ion conductivity is, in general, mainly dependent on the presence of oxide ion vacancies, and these vacancies should be disordered for fast ionic conduction. The highest oxide ion conductivity of 0.17 S/cm was reported at 800 °C in air for disordered perovskite-type metal oxides with the chemical composition of La0.80Sr0.20Ga0.83Mg0.17O2.815. In spite of a large number of chemical substitutions made so far, no major improvement in the electrical conductivity has been observed in LSGM perovskites. LSGM remains unique with regard to the chemical composition–structure–electrical conductivity relationship. Further attention should be paid to layered or tunnel structures possessing stable cations, in which large concentrations of oxygen vacancies may be introduced by chemical substitutions.

Among the solid lithium ion conductors, the perovskite-type A-site-deficient (Li,La)TiO3 shows the highest bulk ionic conductivity. However, its application in lithium ion batteries is limited due to facile reduction of Ti4+ to Ti3+, which leads to high electronic conduction. Similarly, Ti-containing NASICON phosphates are also limited in their application in spite of their high ionic conductivities. The new garnet-structure related compounds in the Li–Ba–La–Ta–O system presently appear to be most important potential candidates for high-energy-density batteries and other applications.

References

Nernst W (1899) Z Elektrochem 6:41

Hangenmuller P, Van Gool W (eds) (1978) Solid electrolytes general principles, characterization, materials, applications. Academic, New York

Rickert H (1978) Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 17:37

Kudo T, Fueki K (1990) Solid state ionics. VCH Verlag GmbH, Weinheim

Köhler J, Imanaka N, Adachi G (1998) Chem Mater 10:3790

Bruce PG (ed) (1995) Solid state electrochemistry. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

B.B. Owens (2000) Solid State Ion 90:2

Rickert H (1982) Electrochemistry of solids. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York

Minh NQ (1993) J Am Ceram Soc 76:563

Steele BCH, Heinzel A (2001) Nature 414:345

Bonanos N (1992) Solid State Ion 53–56:967

Boivin JC, Mairesse G (1998) Chem Mater 10:2870

Thangadurai V, Weppner W (2002) Ionics 8:360

Thangadurai V, Weppner W (2005) In: Ghosh D (ed) Fuel cell and hydrogen technologies. METSOC, Canada, pp 295–310

Robertson AD, West AR, Ritchie AG (1997) Solid State Ion 104:1

Weppner W, Huggins RA (1978) Annu Rev Mater Sci 8:269

Weber A, Tiffee EI (2004) J Power Sources 127:273

Brandon NP, Skinner S, Steele BCH (2003) Annu Rev Mater Res 33:183

Wincewicz KC, Cooper JS (2005) J Power Sources 140:280

Etsell TH, Flengas SN (1970) Chem Rev 70:339

Takahashi T, Iwahara H (1971) Energy Convers 11:105

Steele BCH (1989) In: Takahashi T (ed) High conductivity solid ionic conductors recent trends and applications. World Scientific, Singapore, pp 402–446

Kendall KR, Navas C, Thomas JK, zur Loye HC (1995) Solid State Ion 82:215

Kendall KR, Navas C, Thomas JK, zur Loye HC (1996) Chem Mater 8:642

Goodenough JB (2003) Annu Rev Mater Res 33:91

Subbarao EC, Maiti HS (1984) Solid State Ion 11:317

West AR, Bunsenges B (1989) Phys Chem 93:1235

Ishihara T, Matsuda H, Takita Y (1994) J Electrochem Soc 141:3444

Thangadurai V, Subbanna GN, Shukla AK, Gopalakrishnan J (1996) Chem Mater 8:1302

Ishihara T, Matsuda H, Takita Y (1994) J Am Chem Soc 116:3801

Feng M, Goodenough JB (1994) Eur J Solid State Inorg Chem 31:663

Huang P, Petric A (1996) J Electrochem Soc 143:1644

Huang K, Tichy RS, Goodenough JB (1998) J Am Ceram Soc 81:2565

Ishihara T, Matsuda H, Takita Y (1995) Solid State Ion 79:147

Thangadurai V, Weppner W (2001) J Electrochem Soc 148:A1294

Lybye D, Poulsen FW, Mogensen M (2000) Solid State Ion 128:91

Chen F, Liu M (1998) J Solid State Electrochem 3:7

Ishihara T, Furutani H, Honda M, Yamada T, Shibayama T, Akbay T, Sakai N, Yokokawa H, Takita Y (1999) Chem Mater 11:2081

Huang K, Feng M, Goodenough JB, Milliken C (1997) J Electrochem Soc 144:3620

Schmidt S, Berckemeyer F, Weppner W (2000) Ionics 6:139

Thangadurai V, Beurmann PS, Weppner W (2002) Mater Res Bull 37:599

Thangadurai V, Beurmann PS, Weppner W (2003) Mater Sci Eng B Solid-State Mater Adv Technol 100:18

Hashimoto S, Kishimoto H, Iwahara H (2001) Solid State Ion 139:179

Goodenough JB, Ruiz-Diaz JE, Zhen YS (1990) Solid State Ion 44:21

Goodenough JB, Manthiram A, Paranthaman M, Zhen YS (1992) Mater Sci Eng B Solid-State Mater Adv Technol 12:357

Manthiram A, Kuo JF, Goodenough JB (1993) Solid State Ion 62:225

Yao T, Uchimoto U, Kinuhata M, Inagaki T, Yoshida H (2000) Solid State Ion 132:189

Fisher CA, Islam MS (1999) Solid State Ion 118:355

Fischer W, Reck G, Schober T (1999) Solid State Ion 116:211

Schober T, Friedrich J (1998) Solid State Ion 113–115:369

Abraham F, Debreuille-Gresse MF, Mairesse G, Nowogrocki G (1988) Solid State Ion 28–30:529

Kendall KR, Navas C, Thomas JK, Zur Loye HC (1996) Chem Mater 8:642

Shuk P, Wiemhöfer HW, Guth U, Göpel W, Greenblatt M (1996) Solid State Ion 89:179

Steele BCH (2000) Solid State Ion 129:95

Hibino T, Hashimoto A, Inoue T, Tokuno J-I, Yoshida S-I, Sano M (2000) Science 288:2031

Thangadurai V, Weppner W (2004) Electrochim Acta 49:1577

Kharton VV, Figueiredo FM, Navarro L, Naumovich EN, Kovalevsky AV, Yaremchenko AA, Viskup AP, Carneiro A, Marques FMB, Frade JR (2001) J Mater Sci 36:1105

Inaba H, Tagawa H (1996) Solid State Ion 83:1

Tarascon JM, Armand M (2001) Nature 414:359

Wakihara M, Yamamoto O (eds) (1998) Lithium ion batteries fundamentals and performance. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH, Weinheim

Winter M, Besenhard JO, Spahr ME, Novak P (1998) Adv Mater 10:725

Yu X, Bates JB, Jellison GE, Hart FX (1997) J Electrochem Soc 144:524

Aono A, Imanaka N, Adachi G (1994) Acc Chem Res 27:265

Adachi G, Imanaka N, Aono H (1996) Adv Mater 8:127

Irvine JTS, West AR (1989) In: Takahashi T (ed) High conducting solid ionics conductors, recent trends and applications. World Scientific, Singapore, p 201

Birke P, Weppner W (1999) In: Besenhard JO (ed) Handbook of battery materials. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH, Weinheim, p 525

Thangadurai V, Kaack H, Weepner W (2003) J Am Ceram Soc 86:437

Inaguma Y, Liquan C, Itoh M, Nakamura T, Uchida T, Ikuta H, Wakihara W (1993) Solid State Commun 86:689

Birke P, Scharner S, Huggins RA, Weppner W (1997) J Electrochem Soc 144:L167

Stramare S, Thangadurai V, Weppner W (2003) Chem Mater 15:3974

Aomo H, Sugimoto E, Sadaoka Y, Adachi G (1989) J Electrochem Soc 136:540

Thangadurai V, Weppner W (2002) Ionics 8:281

Shannon RD (1976) Acta Crystallogr A Found Crystallogr 32:751

Hyooma H, Hayashi K (1988) Mater Res Bull 23:23

Abbattista DF, Villino M, Mazza D (1987) Mater Res Bull 22:1019

Mazza D (1988) Mater Lett 7:205

Thangadurai V, Weppner W (2005) J Am Ceram Soc 88:411

Thangadurai V, Weppner W (2005) Adv Mater 15:107

Thangadurai V, Weppner W (2005) J Power Sources 142:339

Thangadurai V, Adams S, Weppner W (2004) Chem Mater 16:2998

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Thangadurai, V., Weppner, W. Recent progress in solid oxide and lithium ion conducting electrolytes research. Ionics 12, 81–92 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11581-006-0013-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11581-006-0013-7