Abstract

The task of adapting cities to the impacts of climate change is of great importance—urban areas are hotspots of high risk given their concentrations of population and infrastructure; their key roles for larger economic, political and social processes; and their inherent instabilities and vulnerabilities. Yet, the discourse on urban climate change adaptation has only recently gained momentum in the political and scientific arena. This paper reviews the recent climate change adaptation strategies of nine selected cities and analyzes them in terms of overall vision and goals, baseline information used, direct and indirect impacts, proposed structural and non-structural measures, and involvement of formal and informal actors. Against this background, adaptation strategies and challenges in two Vietnamese cities are analyzed in detail, namely Ho Chi Minh City and Can Tho. The paper thereby combines a review of formalized city-scale adaptation strategies with an empirical analysis of actual adaptation measures and constraints at household level. By means of this interlinked and comparative analysis approach, the paper explores the achievements, as well as the shortcomings, in current adaptation approaches, and generates core issues and key questions for future initiatives in the four sub-categories of: (1) knowledge, perspectives, uncertainties and key threats; (2) characteristics of concrete adaptation measures and processes; (3) interactions and conflicts between different strategies and measures; (4) limits of adaptation and tipping points. In conclusion, the paper calls for new forms of adaptive urban governance that go beyond the conventional notions of urban (adaptation) planning. The proposed concept underlines the need for a paradigm shift to move from the dominant focus on the adjustment of physical structures towards the improvement of planning tools and governance processes and structures themselves. It addresses in particular the necessity to link different temporal and spatial scales in adaptation strategies, to acknowledge and to mediate between different types of knowledge (expert and local knowledge), and to achieve improved integration of different types of measures, tools and norm systems (in particular between formal and informal approaches).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urban climate change adaptation strategies are an emerging topic. However, most of the present adaptation strategies still encompass primarily a rural focus. This paper outlines the importance of urban areas as hotspots of risk and the particularities that urban areas encompass. It addresses key impacts of climate change in urban areas. In this regard, selected strategies and studies from different countries around the globe are examined to identify the different direct and indirect consequences of climate change in urban environments and the proposed response strategies, including their adaptation goals as well as the corresponding structural and non-structural measures. Due to the fact that many strategies and studies focus solely on abstract goals and visions, such as creating resilience or risk reduction, the analysis also examines the structural and non-structural adaptation measures proposed in order to go beyond the comparison of general goals. The review of selected urban adaptation strategies worldwide provides an important background for the identification of core issues and key questions regarding urban climate change adaptation, which then serve as a framework for a more in-depth and specific analysis of adaptation strategies and challenges in Vietnam, which is widely considered to be amongst the countries most affected by actual and future climate change impacts. In particular, a recent climate change impact and adaptation study for Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC) is analyzed in more detail and juxtaposed with findings of an empirical analysis on adaptation measures at household level in Can Tho City in the Mekong Delta. The juxtaposition of formal adaptation strategies at city level and informal local adaptation processes at micro-scale is used to explore the mismatches and gaps between these processes and to identify core themes in the need for more integrated approaches. Following from this, the final part of the paper formulates recommendations for the further advancement of urban adaptation and calls for a second generation of adaptation approaches that bridge existing divides and place more emphasis on integrative and holistic urban adaptation perspectives, encompassing, e.g., the integration of formal and informal strategies or the synchronization of approaches at different temporal and geographical scales. In this context, the concept of adaptive urban governance is introduced and discussed.

Not sufficiently considered: urban adaptation to climate change

Urban areas play a key role in social and economic development as well as in change at global, regional, national, and local scales. With more than half of the world’s population today living in urban areas and as nodal points of political and economic power, decision making, innovation and knowledge, cities—and megacitiesFootnote 1 in particular—are both the drivers and the result of global change, comprising economic, political, socio-cultural and environmental dimensions (Kraas 2007b; Hall and Pfeiffer 2000; Johnston et al. 2002). Climate change implies a whole new quality to this nexus as urban lifestyles and economies are an important source of greenhouse gas emissions, and are estimated to contribute between 75 and 80% to global greenhouse gas emissions.Footnote 2 On the other hand, urban areas are hotspots in view of climate change risks; firstly, due to their high exposure to potential climate-related hazards—two-thirds of all cities worldwide with a population of more than 5 million are located within coastal areas of less than 10 m elevation (McGranahan et al. 2007). Secondly, urban areas at the same time host the afore-mentioned key functions for larger socio-economic systems; and thirdly, they are often characterized by an inherent vulnerability and instability, in particular in larger urban agglomerations of the developing world (Bull-Kamanga et al. 2003; Coy and Kraas 2003; Kraas 2003, 2008; Pelling 2003).

Between 2005 and 2010, the world’s urban population is expected to grow at an average annual rate of 1.98%—almost twice the growth rate of the total world population, which accounts for 1.17% of growth (UN/DESA 2008). In the least developed countries (LDCs) the urban growth rate within the same period is projected to be far above the global average, at 4.10% annually (UN/DESA 2008), implying that challenges related to rapid urbanization have to be viewed in close connection with development aspects.

Although the recognition of rural areas and their adaptation needs with respect to climate change impacts is essential—given that the consequences of climate change might be felt more directly in social-ecological systems depending heavily on agriculture directly linked to natural services and resources—it is interesting to note that far less attention has been given to the question on how to adapt cities and urban governance and planning systems to address climate change adaptation.Footnote 3 In this regard, the International Commission on Climate Change and Development concludes:

“Cities and city dwellers have received too little attention in discussions of climate change impacts and adaptation. (…) Climate change impacts tend to be thought of as rural: floods and droughts in the countrysides affecting crops and farmers, afflicted ocean atolls and loss of forests.” (Commission on Climate Change and Development 2009, p. 98)

Additional studies [see, for example Satterthwaite et al. (2007) as well as Heinrichs et al. (2009)] conclude that inadequate consideration has been given to the vulnerability of urban populations to climate change.

Similarly, a review of internationally financed National Adaptation Programmes for Actions (NAPAs), under the umbrella of the UNFCCC, clearly reveals that most of the current NAPAs focus primarily on initiatives in rural areas. Although most LDCs are characterized by large populations living in rural areas, it is nevertheless noteworthy that only very few of these programmes encompass strategies with particular focus on climate change—and climate change adaptation-related challenges and measures in urban environments—even though these environments are home to a rapidly growing share of the world’s populations, especially in those developing countries. Even fewer of the NAPAs consider the specific question of how urban planning and urban governance need to be modified in order to address climate change adaptation more effectively. In this regard, the consideration of the particularities of urban areas is a key issue.

Particularities of urban areas and challenging pre-conditions for urban climate change adaptation

Given the increasing role of urban areas globally and the various internal processes and constraints (in contrast to rural areas) that implicate substantial challenges (but also opportunities) for urban climate change adaptation, the further advancement of urban adaptation strategies is a key imperative. Particular attention should be paid to the following particularities of urban areas:

-

(1)

Compared to rural areas, urban areas usually imply different scales, in particular in terms of population size and density, area of built-up environment, agglomeration of infrastructure, and speed of development processes and change. The spatial concentration of population, infrastructure and other assets leads to high concentrations in exposure and damage potentials within cities (Hansjürgens 2007; Romero Lankao 2009; Mitchell 1999). At the same time, however, these high concentrations might imply increased opportunities for urban adaptation as they regulate the practicability and, in particular, the efficiency of certain measures (e.g. expensive dyke systems), thereby contributing to their feasibility and (political) acceptance.

-

(2)

Moreover, cities are characterized by interlinkages of various processes and flows (e.g., administrative, financial, economic, social, political, scientific, etc.) and therefore play a key role in the functioning of larger-scale economic and social systems (Olorunfemi 2009). The climate change-related breakdown of cities (particularly megacities and global cities) would therefore easily imply crises phenomena at a larger scale far beyond the city boundaries (Kraas 2003). However, it is important to note that not only do larger systems depend on functions and processes enacted in cities, but that the cities themselves depend on the functions and resources of (the surrounding) rural and peri-urban areas.

-

(3)

At the same time, cities in certain parts of the world (e.g., Asia, Southeast Asia and Latin America) increasingly turn into development hotspots in terms of, for example, social vulnerability, poverty, disparity, social and political instability or ecological and health-related risk (e.g., Fitzpatrick and LaGory 2000; Hall and Pfeiffer 2000; Coy and Kraas 2003; Pelling 2003; Satterthwaite 2004; Kraas 2005; UN/HABITAT 2007). All these trends can have negative impacts on the baseline resilience of urban systems and their populations, hence negatively impacting the preconditions for successful climate change adaptation.

-

(4)

In this context it has also been noted that, despite the devastating potential of large disasters, small-scale everyday hazards are often underestimated in urban areas. When added-up in terms of their impact and damage potential, small hazards can, in many regions of the world, have even more devastating effects than low-frequency large-scale disasters (Bull-Kamanga et al. 2003). In this regard, cities and their peri-urban fringes are inherently areas where cascading effects of natural and man-made hazards are more likely to occur than in rural areas, particularly in the field of coupled natural–technical disasters.

-

(5)

Furthermore, given the high density and mobility of urban populations, disease can spread more easily within and between cities and can affect larger population groups, as demonstrated, for example, by the global spread of SARS in urban areas (see e.g., Glouberman et al. 2006; Bork et al. 2009).

-

(6)

In addition, in many urban areas, particularly in developing countries and emerging economies, rapid growth and expansion has outpaced the development of infrastructure, leading to a lack of service provision with respect to, for example, sewerage systems or effective transportation means for emergency response. This can contribute to an increasing vulnerability to climate change impacts.

-

(7)

Moreover, rapid growth and expansion in those cities often leads to a loss of governability (see e.g., Roy and AlSayyad 2004; Kreibich 2010), an increase in informal activity, and, eventually, a reduction in the capacity of formal players to steer developments and adaptation initiatives in a comprehensive, preventive and inclusive way.

-

(8)

Lastly, urban environments are characterized by a higher persistence regarding their built environment. Actual changes in the built environment and infrastructure usually require longer time periods and imply higher costs than in rural areas.

Despite these urban development challenges, the ‘international development industry has typically failed to properly take into account the importance of the city as the subject of development in its own right’, as Marcus and Asmorowati note (2006, p. 146). Hence, a more focused discussion and evaluation of the existing urban adaptation programmes as well as of the requirements, constraints and limitations but also the opportunities of different urban adaptation strategies is needed.

Impacts of climate change and adaptation strategies in selected urban areas

In contrast to single natural hazards (such as floods, droughts or storms) climate change impacts are characterized by multi-hazard phenomena including the simultaneous occurrence of sudden-onset hazards and creeping changes. While some climate- and weather-related hazard phenomena, such as droughts and floods, have in general been experienced throughout history, they may be altered in terms of frequency and/or intensity through climate change. Climate change also implies new hazards, such as sea level rise or new dimensions of urban heat island effects. Many changes are thus likely to happen at a higher speed and with greater magnitude than ever experienced by modern human societies (e.g., changes in temperature and precipitation patterns). How such trends will develop in detail, however, remains unknown. Thus, the emerging field of urban climate change adaptation must deal with many uncertainties and open questions (Birkmann et al. 2010).

In the past, most strategies and measures in urban development under the heading of climate change have focused on climate change mitigation rather than on climate change adaptation.Footnote 4 The implementation of compact and multi-functional urban structures that prevent urban sprawl and promote ‘cities of short distances’ is just one example of strategies contributing to a reduction of CO2 emissions in cities. Other formal strategies include land use plans, zoning regulations or building codes.

Although the scientific as well as the political community have only recently set out to move urban climate change adaptation higher up the agenda, first endeavours by local governments to formulate adaptation strategies have been attempted. Due to the fact that these official strategies are still very few in number, the authors decided to complement the analysis of existing urban adaptation strategies with additional studies that provide the basis for such strategies. Overall, the following review of current urban adaptation programmes and studies can inform local governments and various stakeholders involved in the development of urban adaptation responses. The review helps to promote a second generation of urban adaptation strategies informed by shortcomings that can be identified in those efforts published to date. In this context, the following analysis of nine selected strategies and studies provides an outline of (1) the various hazards and changes (direct and indirect impacts) urban areas have to deal with due to climate change, as well as (2) the respective response and adaptation measures proposed or already implemented. The review is used here to identify key questions that help to address specific challenges for urban adaptation. Those key questions can then be transferred to guide the analysis in a more specific national or regional context—as we illustrate later in this paper by using the example of Vietnam.

Review of selected adaptation strategies and studies

This review includes urban adaptation programmes and studies (preparatory documents for adaptation strategies) for the cities of Boston,Footnote 5 Cape Town,Footnote 6 Halifax,Footnote 7 HCMC,Footnote 8 London,Footnote 9 New York,Footnote 10 Rotterdam,Footnote 11 Singapore,Footnote 12 and TorontoFootnote 13

While this paper cannot provide an in-depth review of each of the nine examples, it gives instead an overview of the state-of-the-art regarding urban adaptation strategies. In this regard the following criteria were applied within the review:

-

(1)

overall vision and key goals of the adaptation strategy or study;

-

(2)

baseline information used;

-

(3)

identified direct and indirect consequences of climate change;

-

(4)

involvement of formal and informal institutions or organizations; and

-

(5)

proposed measures in terms of structural and non-structural interventions.

Overall vision and key goals of the adaptation strategy or study

It is interesting to note that most of the urban adaptation strategies analyzed embed adaptation in a larger framework of risk reduction and the protection of citizens and infrastructure. That means these strategies start with a detailed assessment of expected climate related hazards and stressors in order to derive specific adaptation strategies and measures—in particular in the cases of Cape Town, HCMC, London, Halifax and Boston. In addition, London and HCMC emphasize more strongly the overall need to create and promote resilience, which is understood as a broader framework in the respective studies. In contrast, Rotterdam underlines in different documents the necessity of, and opportunity for, transformation in the light of climate changes; thus, climate change here is seen as a chance for transformation.

Baseline information used

The analysis of the baseline information used for the formulation of the different objectives and measures reveals that many strategies refer to IPCC scenarios—particularly the documents for Cape Town, Toronto, London, Singapore, HCMC and Rotterdam. Moreover, historical events are used as a point of reference for adaptation measures—in particular in London, Rotterdam and Cape Town. Explicitly localized projections of extreme events using modelling and geographic information systems are undertaken in New York, London, HCMC and Rotterdam.

Identified direct and indirect impacts of climate change

Figure 1 provides an overview of key direct and indirect impacts of climate change in urban areas as outlined in the selected adaptation strategies. The graphic illustrates that some direct impacts are considered to cause much more indirect impacts than others and may, therefore, imply more challenges with respect to comprehensive adaptation strategies. In addition, the figure shows that perceived potential impact-portfolios can vary drastically depending on the geographic location and bio-physical assets of the respective city.

Involvement of formal and informal institutions

Most of the published programmes and strategies evaluated were developed by formal city organizations, such as the Mayor’s Office, an Environmental Department or the authority for an urban agglomeration. The variety of strategies within the respective programmes and studies (see also Table 1) indicates that different departments are, or will have to be, involved in the implementation of the different measures and actions proposed. In some other cases, an inter-agency taskforce was established to review the proposed adaptation measures—for example, in Singapore. In the case of HCMC, the actual study for climate change adaptation was developed by an external consultant in close cooperation with the Peoples’ Committee of the City and the Department of Natural Resources and Environment. In contrast, the adaptation strategies analyzed provide much less information regarding the involvement of civil society, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and/or the private business sector. Some of the urban adaptation strategies, however, have a strong emphasis on consultations of different stakeholders. The climate change adaptation strategy for London for example, formulates within its different chapters (e.g., flooding, drought, overheating, etc.) explicit consultation questions that should be discussed within the broader public.

Discussion of the results

In terms of the overall vision and key goals (see criteria 1), the majority of the reviewed urban adaptation strategies have a ‘risk focus’. Thus, they identify specific climate change-related hazards and threats as a starting point for developing adaptation measures. In some cases, such as in the adaptation strategy for the city of Rotterdam, more emphasis is given to possible transformation due to climate change. Thus this strategy underlines opportunities that climate change might bring for the city, including, for example, new types of infrastructures that allow living with and on the water (water plaza). It is noteworthy that the City’s Action Plan for Adaptation of the city of Cape Town additionally classified goals, strategies and measures into (1) immediate options (no regret); (2) second resort strategies and measures that require further funding; (3) third resort strategies that require further investigation; and (4) future measures (see City of Cape Town 2009, p. 40). This differentiation implies a stronger management approach, including timelines for the implementation of the different goals and measures.

The baseline information used (see criteria 2) within the urban adaptation strategies analyzed often contains both (1) climate change scenarios—particularly referring to the IPCC—and; (2) historical data. However, the review shows that much more information is given for expected future bio-physical changes than for changes that might occur in the socio-economic or demographic domain.

The analysis of indirect impacts (see criteria 3), e.g. for human health, are often based on the identification of functional chains and impact-response patterns experienced in the past or modelled for the future using natural science-based approaches. In contrast, the issue of vulnerability—understood as the analysis of inherent characteristics within exposed elements that regulate the susceptibility and coping capacity and thus the level of harm potentially experienced—is far less explored. Furthermore, it is evident that although many strategies and studies aim at an integrative approach, the actual measures proposed are often characterized by sectoral policy approaches (see Table 1). In terms of indirect impacts, climate change can intensify or even trigger natural-technical hazards and hazard cascades (see Fig. 1, the example of vector borne diseases). This can be seen, for example, in the case of overlaying heat stress and air pollution. The aggravation of water quality problems due to low water levels in rivers and lakes during drought periods and the continuous contamination due to urban water uses are additional cases (see Fig. 1).

Regarding the societal response, the selected urban adaptation strategies reveal that structural measures and non-structural measures (see criteria 5) at present are more advanced for hazards experienced in the past such as flooding. For example, there are no precise explanations on how to deal with sea level rise using non-structural measures (see Table 1). Additionally, the level of detail provided, in terms of structural measures, is in most of the strategies and studies much higher than the details provided for non-structural responses. While flood or coastal defence structures, such as dykes, walls or gates (e.g. the Thames Barrier in London or other dyke programmes) are often described in detail, also providing the financial figures regarding the costs of these measures, far less information is given regarding the actual implementation strategy or costs for non-structural measures. Moreover, the strategies and studies examined provide only limited information regarding secondary effects or negative consequences that the proposed structural adaptation measures may entail, such as forced relocation due to the construction of dyke systems (compare Table 1). In this regard, mismatches and potential conflicts between different adaptation measures deserve more attention. Illustrative examples for this problematic nexus include the issues that dyke constructions in the past often propelled further urban growth into high flood risk areas (see also Table 1—flood adaptation measures). Further, the documents reviewed neglect mismatches that may exist between the goal to establish robust (protection) infrastructure and the aim—stated at the same time—to allow for flexibility within response mechanisms in order to be able to adjust to future (uncertain) developments.

The involvement and interplay of formal agencies (e.g., public administrations) and informal organizations (e.g., individual households, non-formalized social networks) (see criteria 4) is difficult to analyze and rarely acknowledged in these documents. Most urban adaptation strategies do not outline how, in particular, informal organizations are involved within risk assessment as well as in the formulation and implementation of the adaptation strategy. However, especially the strategies for London and Rotterdam put emphasis on the involvement of the broader public. For example, the Rotterdam Climate Proof Programme—developed largely by the water management department—outlines strategic public–private stakeholder alliances as well as the need for the engagement of NGOs. An important, yet rarely addressed question for (future) adaptation strategies is how to integrate formal and informal organizations, processes and measures.

Core issues and key questions for the in-depth analysis of urban adaptation in Vietnam

Based on the findings of the review of international urban adaptation strategies and studies, the following section derives core issues and key-questions that can guide the more in-depth analysis of the urban adaptation strategy for HCMC and the adaptation processes identified in the city of Can Tho:

-

(1)

Knowledge, perspectives, uncertainties and key threats

-

What is the knowledge base and background information used to derive recommendations for adaptation strategies?

-

What are the main hazards the adaptation strategy deals with?

-

How far do the strategies and respective assessments consider future socio-economic trends (e.g., migration, demography, poverty or social security) besides the expected changes in the bio-physical hazard patterns?

-

Does the adaptation strategy or study apply an integrative (cross-sectoral) and multi-hazard approach?

-

Does the adaptation strategy take hazard cascades and aggravation effects of already existing problems into account?

-

How does the adaptation strategy deal with uncertainties?

-

-

(2)

Characteristics of concrete adaptation measures and processes

-

What are the structural and non-structural measures proposed or undertaken in the light of climate change adaptation?

-

Do structural and non-structural measures complement each other?

-

How do adaptation strategies deal with potential conflicts between the aim to strengthen the robustness of structures and the need for flexibility in terms of future adjustments?

-

-

(3)

Interactions and conflicts between different strategies and measures

-

To what extent are the formal measures proposed evaluated in terms of their potential effectiveness and secondary consequences?

-

Are (potential) negative externalities of and resulting conflicts between different adaptation measures outlined and transparently discussed?

-

What information is given on the interactions and conflicts between formal and informal adaptation processes, strategies and measures?

-

-

(4)

Limits of adaptation and tipping points

-

Are limits of adaptation outlined or discussed?

-

Do adaptation strategies consider potential or actual tipping points, i.e., the opportunity that systems might shift or collapse due to the inability to cope and adapt to stresses beyond certain thresholds?

-

Against this background of identified core issues and key questions, the following section provides an in-depth case study using the example of Vietnam. This country was chosen based on the fact that, firstly, it is undergoing substantial urbanization and, secondly, it is widely considered to belong to the countries most at risk from climate change impacts.

Urbanization, management and planning challenges in Vietnam

Vietnam is undergoing profound urbanization, with cities and towns playing an increasingly important role in the Republic’s overall economic and social fabric. Having long been a country with a comparatively low level of urbanization, Vietnam’s urban agglomerations have been experiencing substantial growth, in particular since the commencement of political and economic reforms towards a market-based economy (doi moi) in the second half of the 1980s (Forbes 1995; Revilla Diez 1995). While in the year 1985 less than 20% of the country’s population was living in urban areas (equalling some 11.5 million people), this figure rose to nearly 30% in 2009 (accounting for over 26 million citizens; UN/DESA 2008). The United Nations estimates that the urban population will almost double by 2035, and will contribute 57% to Vietnam’s total population by 2050 (UN/DESA 2008).

The numbers indicating the economic importance of Vietnam’s urban sector are even more glaring. Already today, the country’s cities and towns are estimated to account for about 70% of the total economic output (Coulthart et al. 2006). An estimated 90% of all Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is concentrated in HCMC and Hanoi (Yeung 2007, p. 283). It can be expected that the economic importance of Vietnam’s cities will continue to increase as the country’s economy continues its transformation towards the industry and service sectors, and as the role and integration of Vietnam as player in the global economy continues to grow, particularly with respect to growing urban competitiveness among the leading Southeast and East Asian cities (Kraas 2004).

This (observed and expected) growth, in combination with comprehensive political and administrative reforms, implies substantial challenges for urban governance and sustainable urban development in Vietnam—in particular with respect to the provisioning of adequate infrastructure and housing. A comprehensive World Bank study on infrastructure challenges in Vietnam’s cities concluded, for example, with respect to the provisioning of drainage and sewerage infrastructure—one of the most important infrastructure elements with respect to climate change-induced flooding—that the government’s target of ‘achieving 100% coverage in urban areas by 2010 must be regarded as impossible to achieve, given the low starting point’ (Coulthart et al. 2006). In 2006, for example, only about 41% of urban areas in Vietnam had a reticulated sewerage system (Lang 2006, p. 378). Similarly, residential development cannot keep pace with the rapidly increasing demand. Despite the fact that Vietnam achieved an average GDP growth rate of around of 7% between 1993 and 2004, and reduced the official figures of poor people in urban areas from 25 to 3.6% (according to official statistics, Coulthart et al. 2006), an estimated 47% of the urban population still had to live in slum-like conditions with substandard housing and squalor in the year 2001 (World Bank 2005).

On top of these problems, climate change implies substantial new risks and resulting management problems for Vietnam’s urban areas. Given the country’s geography, the vast majority of its cities and towns are located in delta regions and/or along the coastline. Resulting from this is a high exposure to increasing risk related to natural hazards, in particular, river floods, typhoons, storm surges and sea level rise. Around 11% of the urban area would be directly affected by a sea level rise of 1 m, making it one of the countries with the largest percentage of urban extent exposed globally (Dasgupta et al. 2007).

The above-mentioned trends and challenges have to be seen in close relation with the configuration of the formal urban planning and management system in Vietnam (Garschagen 2009). Firstly, many of these challenges result from deficiencies within the planning system itself. Yet, secondly, responding to those challenges requires in general a well functioning planning and management system. This system is currently a very complex one that touches upon tasks and responsibilities of various governmental planning agencies across sectoral, horizontal, and vertical boundaries. In addition, players from the private business sector play an increasingly important role as they continuously gain influence and power to shape developments in urban areas (Garschagen and Kraas 2010). Furthermore, non-governmental civil society players have been strengthening their influence on formal action through an increasingly confident articulation of their interests and claims. However, given the political fabric of the country, formal governmental planning agencies still play by far the most powerful role when it comes to urban planning and management.

The various elements within this formal planning landscape in Vietnam can be grouped into three main branches:

-

overall socio-economic development planning (on national to local level);

-

spatial planning (including land use and master planning); and

-

sector planning (including, for example, domains of industry and trade; transportation; agriculture and rural development; labor, invalids and social affairs; science and technology).

In general, the planning framework envisions that spatial plans should follow the directions laid out in the general socio-economic development plans, and the more concrete sector plans through transferring the defined goals into spatial implementation. However, experience shows that in reality this workflow is often broken-up and planning processes are rather fragmented and characterized by low levels of synchronization between different sectors as well as horizontal and vertical levels.

In terms of actual vertical break-up of competencies, Vietnam has been undergoing a series of legal reforms which entail decentralization. The most important of these reforms are the new Law of Land and the Law of Construction (both in effect since 2004; SRV 2003a, b) as well as the Amendment to the State Budget Law in 2002 (SRV 2002) and the Law on Urban Planning in 2009 (SRV 2009). These reforms increased pressure on local urban governments, with responsibilities and tasks often exceeding their capacities and resources (Garschagen 2009). In addition, these reforms made only a very limited contribution to reducing inefficiencies, ineffectiveness and fragmentation within the planning systems and to fostering integrated planning approaches, clearer definition of responsibilities, capacity development and improvement of resource allocation (van Etten 2007, p. 4).

Case study Vietnam: contrasting Ho Chi Minh City and Can Tho

Behind the background of the general urbanization, management and planning challenges in Vietnam, the following analysis takes up the core issues and key questions derived from the international review as a lens to examine adaptation strategies and processes in HCMC and Can Tho.

Case study: Ho Chi Minh City

Knowledge, perspectives, uncertainties and key threats

In terms of the knowledge base and methodology used, the study entitled ‘Ho Chi Minh City Adaptation to Climate Change’ is based mainly on a hazard modelling approach and its combination with current socio-economic structures in the city. The results derived from this exercise indicate potential risks due to extreme events particularly in terms of land use and population exposed. The report, which was developed by the International Centre for Environmental Management and prepared for the Asian Development Bank, in collaboration with the HCMC People’s Committee and the Department of Natural Resources and Environment (DONRE), shows the enormous challenges HCMC will face due to climate change. It underlines that, among other hazards, sea level rise, floods and saline intrusion pose major threats for the city. The study differentiates flooding due to (1) regular floods; (2) flooding in extreme events; and (3) sea level rise. It outlines that a 1-m sea level rise would imply the inundation of about 40% of the area of HCMC. Nevertheless, it should be mentioned that current planning strategies and national target programmes—such as the National Target Programme to Respond to Climate Change—account for the 30-cm sea level rise likely to occur by 2050 (see SRV 2008). The study concludes that about 500 medium-to-large enterprises and about 24,000 small enterprises would be affected and inundated in the given scenarios of sea level rise and extreme events (ICEM 2009, p. 14). Since HCMC accounts for 65% of all manufacturing enterprises in Vietnam, the disruption of industrial estates in the city would have significant socio-economic implications for the whole country.

The HCMC case study and respective strategies for climate change adaptation underline the need for a cross-sectoral approach. However, this study—as in other similar studies—focuses particularly on the natural science aspects that can be modelled and calculated. Complex interactions of coupled socio-ecological systems and transformations within the social system are not sufficiently addressed. Aspects of social vulnerability are outlined solely in terms of current poverty. Hence, future research and conceptual work is needed, particularly in order to improve socio-economic projections and trend scenarios. Along this line of thought, the issue of aggravation effects with regard to already existing problems deserves more attention.

Characteristics of concrete adaptation measures and processes

The report proposes different adaptation measures systematized into engineering options, social response options (e.g. relocation), land use planning, economic instruments, natural system management, sector-specific practices and traditional responses of communities exposed to natural hazards and climate change (see ICEM 2009, p. 17). Even though the approaches identified focus predominantly on structural or technical measures (see Table 2), the study also identifies non-technical or non-structural responses, such as strengthening coping capacities in view of livelihood maintenance of people at risk, particularly farmers and fishermen. However, it often remains unclear how structural and non-structural measures can be coherently combined. Additionally, dyke systems normally require sluice gates for managing the water flow within and outside the city boundaries; these technical measures and related management questions seem to have been overlooked. Most of the measures proposed aim to develop robust structures that often imply a loss of flexibility once implemented.

Interactions and conflicts between different strategies and measures

Only limited consideration is given to interactions and conflicts between different proposed strategies and measures. For example, the goal to provide every group at risk (e.g., residents, farmers, fishermen and the business community) with safe and affordable land raises important questions under conditions of climate change. When considering the extent of potential flooding caused by extreme events and sea level rise it is difficult to understand where these safe areas could be located and how actual relocation processes could be managed considering the magnitude of people and enterprises that would have to be relocated. Even if all the recommended measures of the flood protection strategy—including new dykes—had been implemented (according to the study), large parts of the current housing and commercial as well industrial areas could still be flooded and remain at risk (see ICEM 2009).

Moreover, many strategies proposed, such as better land use planning and improved building codes, although important, do often not sufficiently match the reality, which is characterized rather by a lack of provision of public infrastructure and constraints of formal planning processes in urban development in HCMC. Thus, more research is needed to explore how to improve, for example, land use planning and land management through both formal and informal strategies. The roles of informal social mechanisms of land management are not sufficiently taken into account. This is similar to many other cases in developing countries and countries in transition, although these processes are important for understanding the development in informal settlements and/or slums (see e.g., Kreibich 2010; Kombe and Kreibich 2000).

Additionally, negative consequences or externalities of structural measures, such as dyke systems or relocation, should be discussed and made transparent. Some of the adaptation measures proposed for HCMC will have severe secondary implications not only for the city and its inhabitants, but also for the surrounding urban, peri-urban and rural areas. Consequently, inter-linkages and dependencies need to be addressed more precisely, including, for example, actual and potential migration flows that might increase due to climate change impacts and the implementation of certain adaptation measures.

Limits of adaptation and tipping points

Against the background of the issues discussed above, the adaptation strategy for HCMC indirectly hints towards some limits of adaptation regarding, for example, the inability of the new flood management system to protect all the area of HCMC against extreme floods. In contrast, no information is given in terms of the cultural, social or economic limits of urban adaptation to climate change. Limits of adaptation in HCMC might—among other factors—originate from the constraints of current tools and measures of formal governance systems, such as, in the case of urban planning, the very limited ability to influence informal urban development or to provide appropriate infrastructure to all residents. Consequently, limits of formal adaptation measures need to be made transparent and additional modes of governance have to be taken into account that go beyond purely state-centred formal mechanisms. Finally, an enhanced adaptation strategy for HCMC requires improved information in terms of the issue of uncertainty, particularly regarding the dynamic and complex interactions within direct and indirect coupling processes within socio-ecological systems. This requires among other issues improved information on the various dependencies of urban population on environmental services from surrounding regions.

Case study: Can Tho—potential climate change impacts and adaptation challenges

Can Tho City, located 130 km southwest of HCMC, is the largest city and the economic centre of the Mekong Delta. The city is comprised of eight administrative districts with a total of around 1.2 million inhabitants, of which more than 65% live in areas categorized as urban (GSO 2009). In accordance with the strong urbanization that is expected for the entire country, the current master plan for Can Tho projects a strong increase in its urban and peri-urban population, rising to 1.1 million inhabitants by 2025 (with the total number including the population in Can Tho’s rural areas being projected to reach 1.8 million by the same year; SRV 2006). Due to its location in the low-lying Mekong Delta, Can Tho is widely considered to be exposed to substantial climate change-related risks in the near future.

Knowledge, perspectives and key threats

In terms of key threats, Can Tho will have to deal with a mixture of creeping hazards, such as sea level rise, salinization, increased river bank erosion, changes in temperature profiles, changes in precipitation patterns as well as with an increase in frequency and intensity of extreme events, particularly typhoons, heavy rain events and extraordinary strong flooding. Although tainted with high uncertainty regarding future speed and magnitude, those trends and potential hazards cause great concern amongst planners and government authorities in Can Tho as well as at higher levels. Empirical research in 2009 reveals that the main perceived risks amongst staff members of the local authorities and planning agencies as well as the local population are (1) rising water levels due to sea level rise; (2) resulting risk of intensification of urban flooding (in particular, tidal flooding during the rainy season); (3) risk of higher rain variability and more extreme rain events; (4) risk of increasing wind speeds and typhoon occurrence; and (5) higher risk of river bank erosion, due to changes in run-off and increased velocity. The most important indirect impacts are the flooding and consequential functional breakdown of housing units in formal, and particularly in informal, settlements as well as public buildings (including police stations or government offices); soil salinization and resulting problems for agriculture in peri-urban and rural areas of Can Tho; problems for urban and peri-urban agriculture caused by changes in rain precipitation patterns; and, finally, the risk of health problems, namely vector- and water-borne diseases due to environmental changes caused by higher temperatures, as well as extended flooding periods.

In spite of these perceived and assessed risks, there is, so far, no comprehensive formal adaptation plan that formulates concrete measures in response to climate change in Can Tho. However, the case of Can Tho City can serve as a powerful case study to explore (potential) adaptation strategies, adaptive capacities and limits of adaptation of different socio-economic groups, as well as issues revolving around uncertainty in decision making amongst authorities and planners. The analysis thereby draws on the argument that, for certain hazard types, lessons can be learned from exploring current coping and adaption strategies of population groups who already have to deal with the respective hazards (even though currently not induced primarily by climate change). The case of increased flooding occurrence in Can Tho is discussed below. The household level analysis is thereby based on semi-structured interviews followed by a household survey conducted in October and November 2010, covering in total 588 households in Can Tho City.

Actual adaptation measures and processes

Adaptation to increasing water levels is not a new issue for households located close to rivers and canals in Can Tho. The local population has in recent years been experiencing a substantial increase in water levels in the rivers and canals in the city. Monitoring data reveal a rising trend in yearly maximum water levels in Can Tho’s Hau River (also called Bassac River, one of the Mekong’s main river branches after its split in the Northern Mekong Delta) between the years 1996 and 2007 (Department of Natural Resources and the Environment, Can Tho City 2009). The maximum level in 2007, for example, was more than 25 cm above the level of 1996—with neither year being considered to have experienced extraordinary flood events (Department of Natural Resources and the Environment, Can Tho City 2009). This increase is in line with the observation made in the household survey, in which the vast majority of people interviewed stated to have observed a distinct increase in water levels over the last 10–15 years.

The reasons for this trend are not yet entirely understood or agreed upon in the scientific, and particularly the political, arena. The main controversial question is how much this trend is explained by stochastic variance and by “natural” changes in precipitation and discharge, or to what extent they are attributable to man-made changes such as land use variation (e.g., deforestation or sealing of surfaces) and, in particular, the erection of physical infrastructure upstream (i.e., mainly the massed construction of embankments and dyke systems in the upper Mekong Delta, but also hydro-power plants in upstream riparian countries). If the assertion, shared by numerous observers, that the dyke and dam constructions upstream constitute the most important factor contributing to changing flooding patterns in Can Tho is corroborated by ongoing and future research initiatives, this case would certainly qualify as a formidable example of cross-scale conflicts between different (structural) adaptation measures.

In addition to the rising water levels in the rivers and canals, households reported that they have also experienced an increase in extreme rain events (mainly during the rainy season; however, rainfall events were also stated to occur increasingly during the dry season).

Resulting from those two trends, Can Tho and its citizens have experienced an intensification of urban flooding over the last 10–15 years in terms of frequency and magnitude. In response to this, many households have undertaken efforts to elevate their houses, or the floors of their houses, in recent years, with 71% of the respondents stated to have elevated their entire house or the floor at least once within the last 50 years. Elevation of the floor (the most common technique) is usually done through an infill of clay, sand or gravel with a top layer of tiles or concrete, depending on the financial resources of the respective household. Figure 2 clearly illustrates two major trends regarding these elevation activities. First, the number of cases has increased in recent years (with more than 70% of the elevations having taken place only after the year 2000 despite the fact that the vast majority of the households had already been living in their current locations for much longer). Second, the amount by which the floor is elevated seems to be increasing. While before 1990 there were virtually no cases with a vertical elevation higher than 50 cm, a high percentage of the later elevations range between 50 and 100 cm, with elevations between 75 and 125 cm being quite common between the years 2000 and 2009.Footnote 14

Housing or floor elevation amongst households in Can Tho City. Source: Garschagen 2010

Interactions and conflicts between different strategies and measures

As far as input resources for elevation are concerned, Figs. 3 and 4 clearly indicate that amongst the households interviewed (mainly from low- and medium-income groups) formal governmental support plays only a very limited role in terms of financial support and man-power. Despite the persistent reaffirmation by government cadres that poor people, in particular, are provided with substantial support for housing upgrading and flood mitigation, the actual support given to households for this purpose was very low (Figs. 3, 4). In addition, it has to be kept in mind that, as the survey revealed, many of the exposed households most urgently in need of elevation do not even appear in this figure as they belong to the group that (due to lack of resources) did not even elevate their house at all. Hence, the example shows that this preventive adaptation strategy at the household level is so far not greatly supported by any public governmental support scheme, let alone by a specific formal climate change adaptation framework. Interviews and focus group discussions with official planning agencies and People’s Committee organizations in Can Tho have revealed that the discourse on formal climate change adaptation efforts—although not yet very concrete or formalized—revolve almost exclusively around larger-scale formal response measures planned and implemented by the state (including, for example, resettlement programmes, dyke systems or building codes for new infrastructure).

Besides the aspects of financial support and labour input, an in-depth understanding of other issues related to, for example, costs of elevation and house upgrading; access to building material; social networks; technical know-how: land title; planning security or risk evaluation is necessary to understand this exemplary adaptation strategy. This means that modes of adaptation at the household level in Can Tho depend heavily on the specific situation and context of the respective household or socio-economic group. This context is in turn shaped by a number of aspects that are, at first sight, not or only very indirectly linked to the fields of disaster risk reduction or climate change adaptation. In this regard, the nexus of land title, location, housing condition and socio-economic status of the households is of particular relevance in the area studied, as many poor households lack sufficient resources to acquire land plots and are often forced to build provisional houses on stilts along river banks. Those households hence face increased exposure in addition to their low level of resources available for adaptation.

Limits of adaptation and tipping points

The example of housing elevation—which represents only a small segment of ongoing research on urban adaptation in Can Tho—illustrates that, despite high costs in absolute as well as relative terms, the strategy of floor and/or house elevation in Can Tho proved to be functional for most households in order to adapt to the currently experienced rise in water levels and increased flooding.

However, in view of future climate change-induced hazards, this strategy might, in the long-term perspective, no longer be feasible or sufficient for many households, due to the extreme frequency and magnitude of the expected change. While today most households somehow manage to procure the necessary resources for a one-time elevation of, for example, 40 or 60 cm, climate change impacts would likely require far greater elevation in response to sea level rise or more frequent occurrence of extraordinary high floods. The resources needed for those elevations would likely go beyond the means of many households, in particular amongst poorer groups, which at the same time are often confronted with particularly high adaptation imperatives, given that those households in many cases have to revert to low value land with significantly high exposure to (climate change) hazards.

In addition, the physical characteristics of most houses would lead to an exponential increase in costs once a certain threshold of elevation is exceeded. This is because the floor of a house can only be elevated up to a certain height without having to alter the doors, windows, pipe works, sewerage infrastructure and in particular the ceilings and/or the roof.

Gaps and mismatches in urban adaptation processes

The analysis of selected urban adaptation strategies to climate change worldwide (“Impacts of climate change and adaptation strategies in selected urban areas”), the in-depth examination of the adaptation strategy for HCMC (“Case study: Ho Chi Minh City”), and the juxtaposition of these strategies with coping and adaptation processes at micro-scale in Can Tho (“Case study: Can Tho—potential climate change impacts and adaptation challenges”) hint towards existing gaps and mismatches in adaptation endeavours. The following section will therefore discuss how the role of formal and informal processes and measures, the issue of revisiting traditional structural and large-scale interventions and adaptation measures, the topic of tipping points and limits of adaptation and, finally, the link to overall sustainable urban development could be investigated further.

Linking climate change adaptation to overall sustainable urban development

The review of adaptation strategies above reveals that the emerging discourse around climate change adaptation is in many cases not, or not sufficiently, linked to the discourse on overall sustainable urban development. However, especially in developing and emerging economies, those fields closely influence each other as problems such as insufficient housing and infrastructure or topics of social exclusion and socio-economic disparities strongly affect the baseline vulnerabilities and adaptive capacities amongst specific groups. Yet linkages like these are addressed only insufficiently in most adaptation strategies. Many of the adaptation strategies reviewed rather convey the impression that climate change adaptation is some separate undertaking that takes place detached from other ongoing discourses or even outside the institutional entities usually dealing with issues related to sustainable urban development. In Vietnam, for example, the Departments for Natural Resources and the Environment are the main focal points for climate change adaptation, while entities like the Departments for Construction or the Departments for Labour, Invalid and Social Affairs play a much weaker, if any, role in the formulation of climate change adaptation strategies. Those gaps need to be addressed more rigorously in future in order to promote a more comprehensive and coherent implementation of cross-sectoral adaptation strategies.

Linking formal and informal processes and measures

Formal urban adaptation strategies often concentrate on the formulation of future-oriented strategies and measures (such as the promotion of flood- or storm-resilient houses through the introduction of new building codes or zoning regulations in land use planning). However, as the examples of HCMC and, particularly, Can Tho have shown, it is evident that in many cases people already live in hazard-prone areas and thus already have had to adapt and cope. New building codes and zoning regulations will allow for improved adaptation primarily in newly built-up areas; however, for existing housing structures these measures remain rather ineffective. Hence, the mismatch between the emphasis of formal measures on official adaptation strategies and their actual (lack of) capability to deal with many of the already existing problems needs to be addressed.

The official adaptation discourse in Vietnam (and in many other countries) deals mainly with the state as the key player in planning and implementing adaptation measures. However, based on the findings of the micro-scale analysis in Can Tho, it has been shown that actual adaptation measures are often based on action and agency at household level, rather than on formal broad-scale strategies driven and implemented by state agencies or local governments. Similarly, the case study has illustrated that the actual financial costs and human resources for adaptation may have to be borne by the households themselves. Many current formal responses, such as the afore-mentioned standards in building codes or zoning regulations, often do not match the realities and requirements for upgrading and improving existing structures, particularly at the household level and/or in informal settlements.

In addition, resettlement strategies, as well as bans on urban developments in high risk zones, need to be critically reviewed. The continuous migration into urban areas, as well as the rapid urban expansion, particularly by informal settlements in developing and emerging economies, is a clear indicator that formal measures need to be modified or combined with new tools (e.g., financial or material support regimes for individual households that have no land title and live in high-risk areas), in order to be able to address the needs of those most at risk.

Furthermore, the effectiveness of formal planning instruments is further challenged in many countries by the increasing influence of private land speculators and developers, who are often powerful enough to leverage, for example, formal zoning plans aiming at exposure mitigation (cf. for the Vietnamese case Garschagen and Kraas 2010).

Rethinking traditional structural adaptation measures

The second shortcoming is evident when examining the type of interventions favoured predominantly in formal urban adaptation strategies. In fact, the predominant focus on traditional formal response measures for dealing with extreme events (e.g., dykes, sea walls, gates) might not be sufficient in future as those responses might even engender negative effects across geographical or temporal scales (J. Birkmann, manuscript submitted). Although such measures might be needed (e.g., in HCMC, London, Cape Town), urban adaptation strategies have to more critically review the implications of these measures for their hinterland (e.g., downstream in the case of dykes). In the case of Can Tho, there are strong indications that the construction of embankments and dyke systems upstream contributes to an increased risk of flooding downstream (see “Case study: Can Tho—potential climate change impacts and adaptation challenges”). That means the implications of structural adaptation measures at one place have to be addressed, not solely for the respective territory, but rather regarding their consequences for larger areas and in terms of future adaptive capacities. Consequently, many urban adaptation strategies lack a more holistic regional and temporal perspective—which at the same time implies substantial governance challenges given the fact that most city administrations are (understandably) foremost concerned with impacts and solutions in relation to their own administrative area.

Potential limits and tipping points need to be considered

Tipping points and limits of adaptation are additional key issues that have not been considered sufficiently within many urban adaptation programmes. The case study of Can Tho gives a hint towards the limits of adaptation at the micro-scale, while the adaptation study for HCMC outlines important limitations of current adaptation strategies more indirectly. Considering, in particular, the fact that marginalized and poor urban dwellers very often live in areas most at risk, the effects of cascading risks and potential tipping phenomena can be observed in the sense that shifts in household conditions during a serious crisis situation might eventually lead to a collapse or breakdown of the respective livelihood (see in detail Bohle 2008). A more in-depth discussion of these tipping points, also from a social perspective, is absent in all the formal adaptation strategies reviewed. Furthermore, it is evident that local, provincial and national governments have to prepare particularly for situations in which internal coping and adaptive capacities are overstrained and external support will be essential in order to avoid full or partial collapse of the system.

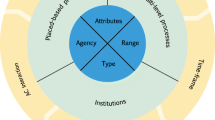

Outlook: from the adjustment of physical structures to adaptive urban governance

Based on the analysis of the challenges, shortcomings and mismatches presented above, the authors introduce the notion of ‘adaptive urban governance’ in order to underline the need for a paradigm shift in terms of moving from the adjustment of physical structures towards a more integrative perspective—also encompassing the adaptation of planning and governance structures themselves as well as of the actions and agency of self-regulating agents. Consequently, urban adaptation cannot be addressed sufficiently through the sole implementation of large-scale structural measures that aim to adjust the built environment. Rather, we argue that, beside physical structures, the planning system and multi-level governance structures also have to change in order to ensure all relevant topics and aspects are covered, and all relevant stakeholders are included. In this regard, the concept of governance helps to broaden the focus.

Governance

Over the last two decades, an intensive discourse on governance has developed that gained substantial influence in both the political and academic arenas (e.g., Stren 2003; Doornbos 2001; Elander 2002). Even though the range of discourses and approaches identified under that label of governance has become very wide and comprises diverse normativisms, epistemologies and ontologies (Pierre and Peters 2000; Grindle 2007; de Alcántara 1998), some common elements can be identified in almost all governance understandings. Governance, thus, describes all ways in which individuals and institutions exercise authority and manage common affairs at the interface of the public, civil society and private sector. It comprises the mechanisms through which individuals, groups and official entities articulate their interests, exercise their legal rights, meet their obligations and mediate their differences (adapted from UNDP 1997). The normative advancement of good governance is understood by UNDP as “participatory, consensus oriented, accountable, transparent, responsive, effective and efficient, equitable and inclusive” and following “the rule of law” (UNDP 1997). A critical and complicated issue in dealing with governance and good governance is to break down these concepts (which originate mostly from a national or even global viewpoint) to a local (urban) focus for research or implementation.

Departing from the general interpretation of governance and good governance, two specific schools of thought in the particular context of urban planning and risk governance, respectively, are worthwhile mentioning. First, in the field of spatial and urban planning, the governance discourse has evolved as a kind of counter-concept to purely state-driven and governmental action. Consequently, governance is distinctly different from government. In this regard, self-regulation through coordination and cooperation is seen as an important strategy to achieve more coherent and integrative planning results (see e.g., Benz 2004; Fürst 2005; Frey 2005; Kraas 2007a).

The second school of thought is linked closely to the field of risk management. In this context, the concept of risk governance defines governance as the totality of actors, rules, conventions, processes, and mechanisms concerned with how relevant risk information is collected, analyzed and communicated, and management decisions are taken (Renn and Graham 2006, p. 80; Renn 2008, p. 289 et seq.).

The value of the different governance discourses for urban climate change adaptation is based on the fact that the entry point of most governance concepts is the critique on purely state-driven interventions or the acknowledgement of state failure in terms of the provision of important services (infrastructure, public transport, etc.). Additionally, governance thinking on this notion also stresses the need to consider both formal and informal domains (Biermann 2007; Biermann et al. 2009).

Adaptive urban governance in that sense also deals with problems of the partial absence of the state and the fact that governance goes beyond formal planning and state regulation (Kraas 2007a). Governance thus underlines the necessity of considering the interplay of formal and informal rule systems addressing the question of how synergies between those two domains can be utilized and formalized.

Based on the international review, the in-depth analysis and the gaps and mismatches identified in the previous sections, key elements for adaptive urban governance in the light of climate change can be formulated as follows:

Considering and linking different spatial and temporal scales

Strategies and tools of adaptive urban governance need to consider and integrate different scales: micro (household scale) adaptation needs; adaptation requirements at city level; and adaptation needs at regional level, particularly taking into account the various city-regional interactions. Furthermore, adaptive urban governance needs to strengthen the perspective on multiple time scales. Besides long-term strategies and projects, also short- and medium-term approaches should be outlined, particularly in terms of their contribution to long-term adaptation. In this regard, the information base also needs to be improved, in particular with respect to projections of future socio-economic developments and vulnerabilities in the city (compare also Garschagen and Kraas 2010). The strategies of urban adaptive governance require new methodological tools (see e.g. Birkmann and Fleischhauer 2009; Birkmann et al. 2010) that go beyond the cost-benefit analysis. Besides direct impacts of adaptation measures, indirect impacts at different scales and time horizons have to be addressed. Finally, urban adaptive governance has to promote more flexible and inclusive governance structures, moving from the management of administrative units to applying flexible units for specific problems and risk phenomena. It might, for instance, be useful to implement drought adaptation programmes solely at larger scales while adaptation concepts for heat stress might need to be based on individual building blocks and types. The question of how the adaptation strategy addresses mismatches between climate stressor scales and political/administrative scales needs to be documented and discussed openly.

Integration of, and mediation between, different types (sources) of knowledge

In terms of different sources of knowledge it has become evident that the majority of formal adaptation programmes are based on expert knowledge. However, the Can Tho case study has also indicated that an important everyday knowledge of people at risk does exist, which is—despite being different in nature—very sophisticated and detailed. The combination of expert and local knowledge, as well as the mediation of different knowledge types, is a key challenge for adaptive urban governance. While local people might have a variety of knowledge on how to deal with hazards and environmental changes experienced in the past—such as floods or droughts—much less knowledge might be available on how to deal with sea level rise or storms in regions that have not yet experienced those phenomena. Therefore, adaptive urban governance has, on the one hand, to integrate and up-scale local knowledge and experiences of people at risk. On the other hand, expert information on likely future (unknown or uncertain) changes has to be communicated, and potential conflicts between past habits and the imperatives resulting from potential future changes mediated.

Consideration and combination of different measures, tools and norms

Legal or illegal action, with or without land title, forced or voluntary resettlement—adaptive urban governance will also have to address challenges of different norm systems and mediation between formal and informal measures to adapt to climate change and various other stressors in urban areas. Besides the challenge of more explicitly integrating formal and informal adaptation measures, innovative synergies between formal and informal tools should be fostered in order to open up new pathways for action. In this regard, the discourse on risk governance (see second school of governance) also underlines the need to bridge formal and informal risk management tools. As the case study of Can Tho illustrates, the most important and effective players in household-level adaptation are workers hired on an individual basis and the household members themselves. As similar “informal” actions are the most important drivers for household-level adaptation of various types, formal governmental adaptation endeavours should utilize this pathway and should support those elements through, for example, target-specific financial support for building materials or labor force.

Conclusions

The paper has identified and discussed various challenges, gaps and mismatches in current urban climate change adaptation strategies and studies that have to be addressed when aiming to improve adaptive urban management in view of climate change impacts. The authors introduced the concept of adaptive urban governance, which calls for a paradigm shift away from the currently dominating assumption that urban adaptation to climate change has to deal predominantly with the adjustment of physical structures towards the integration of a stronger emphasis on the need to adapt procedures and principles of adaptation-assessment, -planning, -implementation and -evaluation itself. Against the background of the findings of the international review and the in-depth discussion of adaptation measures and processes in Vietnam, the authors formulate recommendations for, and key elements of, adaptive urban governance. In particular, the paper stresses the need for a stronger consideration of the inter-linkages between formal and informal action in adaptation; the integration of different knowledge types; assessments of cross scale secondary effects of specific measures; the identification of potential conflicts between given adaptation strategies; the integration of urban climate change adaptation endeavours with initiatives in the wider field of sustainable urban development; and limits and tipping points with respect to adaptation options.

Increased efforts are needed in future to break down and translate those recommendations into concrete governance mechanisms for implementing the identified criteria within the specific cultural, political and administrative context of given countries or cities. In addition, increased emphasis needs to be given to the involvement of different disciplines in order to broaden the discussion, which, to date, is characterized by a strong prevalence for engineering perspectives.

Related to this, research gaps still exist in relation to the tools and procedures used to monitor and evaluate actual modifications within planning processes, as well as within knowledge, awareness and information environments in the context of urban climate change adaptation.

To conclude, urban adaptation strategies and discourses need to deal more strongly with processes and the knowledge base on how to improve adaptive capacities and adaptive planning, rather than focusing solely on a list of options to adjust physical structures and the built environment. The identified key elements for adaptive urban governance can help to structure, guide, and evaluate these processes.

Notes

Megacities are defined mostly in quantitative terms as cities with a minimum of—depending on the source—5, 8 or 10 million citizens (Kraas and Nitschke 2006). In addition, some definitions also include thresholds of population density. While most sources consider only monocentric cities, others also include polycentric agglomerations as functionally integrated mega-urban areas (Kraas and Nitschke 2006).

These figures, however, depend heavily on measurement definitions (e.g., rural vs urban location of products being consumed in rural or urban areas respectively) and, hence, can vary drastically according to definitions and measurement methods (Satterthwaite 2008).

A survey of published peer-reviewed papers, using the search tool ‘Science Direct’, reveals that, between 2000 and 2010, about 13,400 papers can be found on ‘adaptation and agriculture’; about 37,400 on ‘adaptation and water‘, focusing mainly on rural and agricultural water problems; about 9,000 on ‘adaptation and urban’; while only 4,000 papers matched the keywords ‘adaptation and urban planning’. Although some papers might address rural and urban adaptation aspects simultaneously, this comparison of publications in peer-reviewed scientific journals clearly underlines the fact that the scientific arena has paid more attention to climate change adaptation from a rural perspective. Additionally, also other terms such as water and climate change as well as sanitation and climate change were examined. This more in-depth analysis also revealed that urban environments have in general received less attention compared to rural environments.

The authors follow the commonly used terminology in which climate change response comprises the two domains of climate change adaptation and climate change mitigation. Adaptation in this notion refers to the “adjustment in natural or human systems, in response to actual or expected climatic stimuli or their effects, which moderates harm or exploits beneficial opportunities” (IPCC 2007, p. 869). Mitigation comprises all measures that reduce greenhouse gas emissions, limit their growth or enhance sinks. Due to the focus of this paper, the authors have had to limit the discussion here to adaptation measures, fully acknowledging, however, that measures from both domains are absolutely necessary and that ‘mitigation is the best adaptation’ in the long run.

The adaptation strategies identified for Boston are based on the study:‘ Climate’s Long-Term Impacts on Metro Boston’. This study was undertaken by experts from the Tufts University, University of Maryland and Boston University based on a grant provided by the US Environmental Protection Agency. It outlines major risk and adaptation requirements for urban areas in Boston (Kirshen et al. 2004a, b).

In terms of adaptation strategies for Cape Town, we analyzed the study‘ Framework for Adaptation to Climate Change in the City of Cape Town’ by Mukheibir and Ziervogel (2006) as well as the draft‘ City Adaptation Plan for Action to Climate Change for the City of Cape Town (Draft Report City of Cape Town, May 2009) prepared by the City of Cape Town.

The adaptation strategies for Halifax are documented in a community action guide to climate change and emergency preparedness, which was published by the Halifax Regional Municipality (HRM) in 2006.

The adaptation study for HCMC was prepared by the International Centre for Environmental Management (ICEM 2009) in close collaboration with the HCMC People’s Committee and the Department of Natural Resources and Environment (DONRE).

London’s adaptation strategy has been published by the Greater London Authority in August 2008 as a draft.