Abstract

In this study, the effects of heat treatment on the microstructure and mechanical properties of cold sprayed stainless steel 316L coatings using N2 and He as propellant gases were investigated. Powder and coating characterizations, including coating microhardness, coating porosity, and XRD phase analysis were performed. It was found that heat treatment reduced porosity, improved inter-particle bonding, and increased ductility. XRD results confirmed that no phase transformation occurred during deposition. Significant increase in UTS and ductility was observed for the annealed specimens obtained with nitrogen propellant, whereas little changes were observed for the helium propellant produced specimen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cold gas dynamic spray is an emerging coating technique in which micron size powder particles are accelerated by a supersonic gas jet generated through a converging-diverging nozzle and sprayed onto a substrate where they impact, deform, and bond to create a dense coating (Ref 1-5). The technology has become of worldwide interest for its numerous advantages over current thermal spray processes with a prominent advantage being that powder particles remain predominately in the solid state during the entire deposition process, thereby minimizing thermal stresses, oxidation, phase transformation, and grain growth. Due to its benefits, cold spray processing is envisioned for medical devices such as hydroxyapatite coatings for orthopedic implants (Ref 6). Because failure and fractures in coronary stents seem to be attributed to high cycle fatigue (Ref 7, 8), which can be adversely affected by increasing grain size, the use of cold spray coating material has been proposed as an alternative manufacturing choice to the conventional casting and hot and cold forming route for manufacturing coronary stents (Ref 9).

The vast majority of coronary stents are manufactured from 316L stainless steel for its superior corrosion resistance and well-suited mechanical properties (Ref 10-12). Many medical devices, including stents, are primary processed via casting and subsequent thermo-mechanical processing to achieve the required shape and mechanical properties (Ref 13). In the case of stent material, selection of melt source is important to ensure the homogeneity, porosity and micro-cleanliness of the cast alloy (Ref 13, 14). Small stent strut sizes in the range of about 70 μm, which typically result in about three grains across the thickness of the implant, may also affect fatigue resistance (Ref 14). Apart from increasing strength and fatigue resistance, a smaller grain size has a definite advantage in wear properties (Ref 15). The strengthening of metal alloys through grain refinement has drawn much attention in the past decades; but for 316L, a martensitic transformation may occur in the current process that decreases corrosion resistance and increases magnetic susceptibility (Ref 16, 17). Therefore, it is important to develop a process for manufacturing stents and other medical implants that not only refines grains but also maintains the austenitic structure of 316L.

Limited research has been performed on 316L stainless steel coatings using cold spray (Ref 18-24). The formation of recrystallized, nanoscale grains near particle interfaces in the as-sprayed 316L coating (N2 and He-sprayed) was observed through TEM analysis (Ref 18) while EBSD analysis revealed a fully recrystallized microstructure after annealing (compressed air-sprayed coatings) (Ref 23). The latter study also provided results on corrosion behavior of cold sprayed stainless steel 316L coatings exposed in 10% HNO3 and showed increase in corrosion resistance with increasing annealing temperature. The objective of this work is to provide a comprehensive study on the microstructure and mechanical properties of cold sprayed SS 316L coatings in both as-sprayed and heat treated conditions using N2 and He as propellant gases. For comparison purposes, annealed bulk 316L sample was also tested at the same condition.

Experimental Methods

Feedstock Powder

Commercially available stainless steel 316L powder (−45 + 15 μm, Fe-17.0Cr-12.0Ni-2.5Mo, FE-101, Praxair, Indianapolis, IN, USA) was used in the as-received condition as feedstock material. The volume weighted powder size distribution was measured with a laser scattering particle size distribution analyzer (LA-920, Horiba Instruments Inc., Kyoto, Japan).

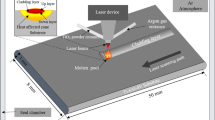

Cold Spray Parameters and Diagnostics

The cold spray system used to produce the coatings was a KINETIKS® 4000 (Sulzer Metco (US) Inc., Westbury, NY, USA) with the 120 mm long pre-chamber configuration. Two types of nozzles were used: MOC24 (Cold Gas Technology, Ampfing, Germany) and VH70 (ASB Industries Inc., Barberton, OH, USA) for N2 and He propellant gases, respectively. Details on the nozzle materials and dimensions can be found elsewhere (Ref 25). The propellant gas temperature was limited to 700 and 350 °C with the MOC24 and VH70 nozzles, respectively, due to the occurrence of either nozzle clogging or rapid nozzle degradation, respectively, above these temperatures with the 316L powder.

Table 1 shows the process parameters used for producing the samples, which were chosen on the basis of particle velocity measurements using an optical time-of-flight diagnostic tool (ColdSprayMeter, Tecnar Automation, St. Bruno, QC, Canada) (Ref 26). The average particle velocities measured in free jet were 838 ± 84 and 996 ± 138 m/s for N2 and He propellant gas conditions, respectively. The stainless steel 316L powder was cold sprayed onto grit-blasted, mild carbon steel plates (140 × 100 × 3 mm) to obtain a nominal coating thickness of 3 mm. Following deposition, electric discharge machining (EDM) was employed to separate the deposited material from the substrate and all subsequent testing and microstructural analysis was performed on the coating material only.

Heat Treatment

Isothermal heat treatments of 1 h were performed in air using an electric resistance furnace and subsequently air cooled. The number of investigated heat treatment temperatures varied by coating type and test method: 400, 700, 750, 800, 1000, and 1100 °C for microstructure and microhardness characterization of N2 and He-sprayed coatings; 400, 800, 1000, and 1100 °C for tensile testing of N2-sprayed coatings; and 1000 and 1100 °C for tensile testing of He-sprayed coatings. The surface oxidation layer of tensile specimens was removed using SiC backed grinding paper.

Microstructural Characterization

Samples were sectioned perpendicular to the spray direction, hot mounted in resin, mechanically ground, and polished using standard metallographic preparation procedures. An aqueous solution of 45 mL HCl, 15 mL HNO3, and 20 mL methanol was used for etching. A field emission-scanning electron microscope (Philips XL30, Eindhoven, Netherlands) was used to characterize the powder and coatings. The cross-sections of as-sprayed and annealed coatings were also characterized by electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) using the Philips XL30 fitted with a TSL system. The accelerating voltage used was 20 kV and the step size was 70 nm. For EBSD characterization, an additional metallographic step to remove the deformed surface layers was included wherein samples were vibratory polished using colloidal silica for a minimum of 4 h. The coating porosity was measured using image analysis (Clemex Vision, Clemex Technologies Inc., Longueuil, QC) on a minimum of 10 random fields obtained in the backscattered electron mode (BSE) at 500× magnification. X-ray diffraction (XRD) studies of the powder and the coatings were carried out using a Bruker x-ray diffractometer (Co Kα radiation, 40 kV, 40 mA, 0.02°/s scan rate). Following tensile testing, the fractured surfaces were examined with secondary electron imaging.

Mechanical Testing

The coating hardness was measured using a Vickers microhardness tester (Clark CM100AT, SUN-TEC Corp., Novi, MI, USA) at a load of 0.98 N for a minimum of 10 measurements taken at random locations on the polished cross-section of coatings. Tensile tests were performed on a MTS 810 (MTS Systems Corp., Eden Prairie, MN, USA) at room temperature and a strain rate of 10−3 s−1. Specimen elongation was assumed equal to the crosshead displacement and load-displacement measurements were converted to (engineering) stress-strain values. Samples of 2.2 mm thickness were prepared according to ASTM E8 (Ref 27) for rectangular tension test subsize specimens (25 mm × 6 mm gage dimensions) with a tensile direction perpendicular to the spray tracks. Tensile samples were polished to make the specimen surfaces consistent and relatively defect free. Two tensile tests were performed for N2-sprayed coatings at each condition while only one specimen was tested for He-sprayed coatings.

Results and Discussion

Feedstock Powder

The particle size distribution of the 316L powder, shown in Fig. 1, exhibits a d10, d50, and d90 of 11.7, 29.0, and 52.7 μm, respectively. Analysis of the feedstock powder revealed that the average microhardness was 185 ± 15 HV0.1. Figure 2 shows the irregular morphology of the powder, although a few (near-) spherical particles were also observed.

Coating Characterization

Effect of Propellant Gas and Annealing Temperature on Porosity and Particle-Particle Bonding

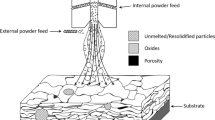

Figures 3 and 4 show typical cross-sectional views of the as-sprayed and heat treated coatings produced using N2 and He as propellant gases, respectively. In the as-sprayed condition, the coating sprayed with He as carrier gas exhibited lower porosity compared to the coating sprayed with N2 (0.2 ± 0.1 and 1.6 ± 0.3%, respectively) due to a higher particle impact velocity (838 ± 84 m/s and 996 ± 138 m/s, respectively) and an associated greater degree of plastic deformation. A decrease in porosity was obtained for the N2-sprayed coating after annealing at temperatures up to 800 °C, as shown in Fig. 5. For N2-sprayed coatings after high temperature annealing (800-1100 °C), and He-sprayed coatings at all conditions, measured porosity values were low (≤0.2).

For N2-sprayed coatings (Fig. 3), “cracks” were observed in the as-sprayed material due presumably to incomplete bonding of particle-particle interfaces. After heat treatment, however, fewer inter-particle interfaces were observed and fine scale porosity was presented (arrowed in Fig. 3e). This effect was partially observed at 400 °C and well advanced at 1100 °C. For He-sprayed coatings (Fig. 4), inter-particle boundaries were not observed in the as-sprayed condition and microstructures after heat treatment up to 800 °C were similar. Fine pores were also observed for He-sprayed coatings at higher temperatures (≥1000 °C), although fewer in comparison to the N2-sprayed coatings. Due to its small scale, the development of these pores did not appear to significantly increase the total measured values (i.e., ≤0.2% porosity for all He-sprayed coatings). The decrease in porosity with increasing annealing temperature in the N2-sprayed coatings can probably be explained by the usual sintering models. The fine porosity observed in both He and N2-sprayed specimens after high temperature annealing may be due to incomplete “sintering” at inter-particle interfaces that have not been metallurgically bonded. In addition, the porosity viewed in the He-sprayed coating annealed at 1100 °C suggested that cracks were present in the as-sprayed coating despite not being clearly observed in the as-polished cross-section.

The etched, cross-sectional microstructures of as-sprayed and heat treated coatings deposited with N2 and He as propellant gases are shown in Fig. 6 and 7, respectively. At lower heat treatment temperatures of 400 and 800 °C, incomplete bonding between particles for N2-sprayed coatings was assumed as inter-particle boundaries (arrowed in Fig. 6b) were still present. At 1000 and 1100 °C, however, inter-particle interfaces appeared to have been replaced by (or transformed to) pores (arrowed in Fig. 6d) and particle microstructures revealed equiaxed grains and annealing twins throughout the structure. In general, the He-sprayed coatings displayed similar features to the N2-sprayed coatings. Although porosity appeared greater in the He-sprayed coatings in these etched micrographs, the observed porosity was highly dependent on the etching (e.g., etch time).

Precipitates were also observed in the etched microstructures, which can potentially influence mechanical and corrosion properties (e.g., due to chromium depletion). These precipitates (principally M23C6 and Laves phases in 316L) may have been formed during the annealing or the relatively slow air cooling from higher temperatures (Ref 28). According to the time-temperature-precipitation (TTP) diagram for 316 (Ref 29), M23C6 can precipitate after 1 h at temperatures greater than ~650 °C.

Effect of Propellant Gas and Annealing Temperature on Recrystallization

Figures 8 and 9 show EBSD inverse pole figure (IPF) maps at various magnifications (i.e., 500× to 8000×) revealing grain orientations for the as-sprayed and annealed samples produced using N2 and He as a processing gas, respectively. In general, the coatings exhibited a random texture for all annealing conditions. Although large un-indexed regions (black and white) were obtained for maps of as-sprayed coatings, these areas were reduced as the annealing temperature increased. The decrease in un-indexed regions was attributed to microstructural restoration (i.e., recovery and recrystallization) of the deformed structure as these areas may be due to imperfections such as the high levels of particle deformation, presence of porosity, or incomplete bonding between particles.

For N2-sprayed coatings, there were regions of very fine grain size in the as-sprayed coating and after annealing up to 700 °C. Within some particles, these grains were observed in a necklace at the particle boundary (circled in Fig. 8a), which is generally associated in cold spray with a high deformation region. Larger equiaxed grains were developed at intermediate temperatures of 750 and 800 °C and above these temperatures, the fine grains were generally absent. A relatively uniform microstructure of equiaxed grains suggested that recrystallization was complete at 1000 °C with further grain coarsening obtained after annealing at higher temperature. The EBSD map obtained for the as-sprayed He-sprayed coating displayed a larger non-indexed area than the N2-sprayed coating, which was attributed to a higher degree of deformation at higher particle velocity. A microstructure with pancaked grains was still observed for the He-sprayed coating at 1000 °C in contrast to the N2-sprayed coating. Although the cause was unknown, grains in the lower portion of the micrograph, which appeared to be more equiaxed (circled in Fig. 9f) than those of the upper portion, may be an indication that the mapped area was within an inhomogeneous deformation region (i.e., difference in driving force for recrystallization). Annealing at 1100 °C produced a fully recrystallized microstructure similar to the N2-sprayed coating, although grain coarsening was significantly less (note that corresponding maps in Fig. 8g, 9g are at different magnifications). The fine-scaled, un-indexed (white) spots observed within particles of some maps (e.g., Fig. 9g) may be related to precipitates, as observed for 316L-Co-Cr coatings in a previous study by the authors (Ref 9). EBSD analysis at higher magnifications appears necessary to adequately reveal the precipitation behavior at the various heat treatment conditions in this study. However, due to the observed effects of porosity and/or particle bonding defects on mechanical properties (detailed in section 3.3), further analysis of precipitation behavior was not performed.

The measured grain sizes, shown in Fig. 10, for well indexed maps (i.e., annealing at 750, 1000, and 1100 °C) were similar for annealed N2 and He-sprayed coatings except at the highest temperature. For comparison, the bulk sample displayed a mean grain size with a relatively large standard deviation of 10.0 ± 8.4 μm. Fine grain sizes were observed after annealing at 750 °C (0.6 ± 0.3 μm for N2 and He-sprayed coatings) with slightly coarser grains at 1000 °C (1.0 ± 0.5 and 0.8 ± 0.3 μm for N2 and He coatings, respectively). At 1100 °C, however, a larger increase in grain size for the N2-sprayed coating was obtained compared to the He-sprayed coating (7.3 ± 4.2 and 1.0 ± 0.6 μm, respectively, over measured image areas of 10,600 and 660 μm2, respectively), which indicated that recrystallization was completed earlier for the N2-sprayed coating (i.e., longer time for grain coarsening). The higher spray temperature for N2-sprayed coatings, which could produce a more recrystallized structure in the as-sprayed condition may be a potential cause of this behavior. In this study, a constant holding time of 1 h was employed for heat treatment of all specimens. However, the results indicate that a longer holding time (at 1100 °C) may be used for He-sprayed coatings to obtain a grain size comparable to that of the N2-sprayed coating. In addition to grain size effects, the use of a longer heat treatment at constant temperature will increase the time available for the diffusion necessary in “sintering” of particle-particle interfaces (section 3.2.1).

XRD Analysis

The XRD pattern of the 316L powder along with the as-sprayed and selected heat treated specimens deposited with N2 is shown in Fig. 11. It can be seen that the characteristic austenitic FCC crystalline structure peaks (γ phase) are present in the powder. In addition, the weak intensity peak observed at 2θ ≈ 52.2° corresponds to the 110 reflection of the martensitic α phase. The XRD pattern of the as-deposited coating exhibits the same set of peaks indicating that there was neither phase transformation nor oxide phase formation during deposition, with, however, a significant peak broadening. Based on a Williamson-Hall plot analysis, the peak broadening can be attributed to a combination of grain refinement and microstrain; both most probably resulting of the work hardening caused by the severe particle deformation that experience the powder particles during coating build-up. The XRD histogram obtained after annealing at 400 °C is similar to the one obtained as-sprayed with a slight increase in grain size based on the Williamson-Hall analysis. However, from annealing of 800 °C and higher, no α (111) peak can be seen, while the γ phase peaks now show typical polycrystalline structure.

Mechanical Behavior of Coating

Effect of Propellant Gas and Annealing Temperature on Microhardness

The microhardness of the N2 and He-sprayed coatings as a function of heat treatment temperature is plotted in Fig. 12. Due to a higher amount of work hardening in the as-sprayed condition, the He-sprayed coating had a higher microhardness than the N2-sprayed coating and both as-sprayed coatings had higher values than the as-received powder (393 ± 14 HV0.1, 452 ± 16 HV0.1 and 185 ± 15 HV0.1 for N2-sprayed coating, He-sprayed coating, and powder, respectively). The hardness values of He-sprayed samples were consistently higher than N2-sprayed coatings at respective annealing temperatures, although similar values were obtained for fully recrystallized microstructures (e.g., at 1100 °C). For coatings deposited with N2 or He, the microhardness profile displayed four stages: (i) no change up to 400 °C; (ii) a gradual decrease from 400 to 700 °C due to a mixture of recovery and a small level of recrystallization; (iii) a sharp decrease from 700 to 800 °C corresponding to recrystallization; and (iv) a considerably slowed rate of decrease in hardness above 800 °C probably associated with the completion of recrystallization and grain coarsening.

Effect of Propellant Gas and Annealing Temperature on Tensile Properties

Stress-strain curves for N2-sprayed coatings and the dependence of tensile strength (UTS) and elongation at fracture (Elf) on annealing temperature for both N2 and He-sprayed coatings are shown in Fig. 13. For N2-sprayed coatings, tensile strength and ductility were very low in the as-sprayed condition (113 ± 5 MPa UTS; 1.3 ± 0.1% Elf) and after annealing at 400 °C (91 ± 9 MPa; 1.0 ± 0.1%). A significant increase in strength was displayed at 800 °C (349 ± 56 MPa; 3.7 ± 1.0%) while both strength and ductility were increased at 1000 °C (571 ± 50 MPa; 14.2 ± 1.1%). Although relatively large variations in tensile strength measurement (i.e., ~50 MPa) were obtained, a decrease in tensile strength was observed at 1100 °C (433 ± 39 MPa; 22.7 ± 3.6%) relative to 1000 °C due potentially to grain coarsening. The cause of the yield point behavior observed (e.g., 1100 °C in Fig. 13a) was not determined due to the complexity associated with the multiple constituents and interactions of the microstructure (e.g., particles, inter-particle boundaries, porosity, precipitates, etc.). In comparison to the coatings, the bulk sample displayed significantly higher tensile strength and ductility (1048 ± 6 MPa; 91 ± 11%). In general, the tensile test results of He-sprayed coatings in this study were considered with caution due to experimental error and the testing of only one specimen at each condition. Even though slippage in the tensile grips was obtained during testing of as-sprayed specimen, the tensile strength (230 MPa) was approximately twice the N2-sprayed coatings. In contrast, however, He-sprayed specimens annealed at 1000 and 1100 °C showed relatively lower strength and ductility values (202 MPa; 10.6% and 230 MPa; 12.8%, respectively) compared to the respective N2-sprayed coatings. For heat treated copper coatings, the opposite has been reported with He-sprayed coatings showing higher ductility than N2-sprayed coatings due to a larger area of well-bonded particles (Ref 30). The rather surprising result in the current study was potentially attributed to interconnected defects in the coating, as perhaps indicated in the porosity characteristics comparing Figs. 6 and 7, and as discussed below in the fracture analysis.

Figures 14 and 15 show typical fracture surfaces of coatings processed using N2 and He propellant gases, respectively. The fracture surface of the sample annealed at 400 °C was similar to the as-sprayed condition with cracks mainly initiated at particle-particle interfaces and no evidence of dimple rupture. However, the fracture of samples annealed at higher temperature, in particular 1000 and 1100 °C, displayed a largely dimpled surface (Fig. 14d, e, respectively). In comparison to the as-sprayed coatings using N2 gas (Fig. 14a), most of the spray particles in the as-sprayed coating using He gas (Fig. 15a) appeared to be strained and some dimples were observed. For annealed specimens at 1000-1100 °C using either N2 or He, there was no significant difference in the dimpled structure. However, at lower magnification, shown in Fig. 16 for 1000 °C, large interconnected defects over a significant area were observed in the He-sprayed coatings (arrowed in Fig. 16b). As these features were not observed in the annealed N2-sprayed coatings, they may represent regions of weaker bonding and serve as a potential cause of the lower than expected tensile strength of annealed He-sprayed coatings.

Although tensile testing of the He-sprayed coatings was problematic (as noted above), the use of helium as a propellant gas produced a coating exhibiting a higher tensile strength compared to nitrogen in the as-sprayed condition. The He-sprayed coating had a lower porosity (0.2 and 1.6% for He and N2, respectively) due to impact particle velocities that were higher by ~160 m/s; however, the measured porosity was still relatively low in both cases. The degree of inter-particle bonding in the as-sprayed condition was another potentially significant difference with as-polished N2-sprayed coatings displaying crack-like defects not observed in He-sprayed coating and the appearance of dimples on the fracture surface of the He-sprayed coating, which was not observed in the N2-sprayed coating.

The N2-sprayed coating generally experienced an increase in tensile strength and ductility with increasing annealing temperature. Although annealing decreases porosity (from 1.6 to ≤0.2%), the tensile properties were higher than those of an as-sprayed coating with similarly low porosity (≤0.2% for He-sprayed coating), suggesting that porosity is not a factor. The fracture surfaces revealed that the strength and ductility increases for the N2-sprayed coating were strongly related to the appearance of dimples (800 °C, Fig. 14c), which coincided with significant jumps in the tensile strength and elongation at fracture values. Both porosity and fracture observations suggested that inter-particle bonding was responsible for the mechanical property improvements. Consequently, although grain refinement was partially negated by coarsening at the highest temperatures, heat treatment was an overall benefit to the strength and ductility of the 316L cold sprayed coatings.

Conclusions

Cold spraying using either N2 or He propellants has been successfully employed to produce dense 316L coatings with no phase change obtained during deposition. Low porosity (≤0.3%) was obtained for He-sprayed coatings in the as-sprayed condition and N2-sprayed coatings annealed at temperatures ≥800 °C. Annealing of N2-sprayed coatings also increased tensile strength and ductility, although tensile properties were lower than the bulk material due to defects remaining in the annealed coating (e.g., porosity, incomplete bonding, etc.). EBSD analysis revealed that annealing at a temperature ≥1000 °C produced a uniform, fully recrystallized microstructure with grains more refined than the bulk material.

References

E. Irissou, J.G. Legoux, A.N. Ryabinin, B. Jodoin, and C. Moreau, Review on Cold Spray Process and Technology: Part I—Intellectual Property, J. Therm. Spray Technol., 2008, 17(4), p 495-516

R.G. Maev and V. Leshchynsky, Introduction to Low Pressure Gas Dynamic Spray: Physics & Technology, Wiley, New York, 2008

T. Schmidt, H. Assadi, F. Gartner, H. Richter, T. Stoltenhoff, H. Kreye, and T. Klassen, From Particle Acceleration to Impact and Bonding in Cold Spraying, J. Therm. Spray Technol., 2009, 18(5-6), p 794-808

A. Papyrin, V. Kosarev, K.V. Klinkov, and V.M. Fomin, Cold Spray Technology, Elsevier Ltd., Amsterdam, 2006

V.K. Champagne, The Cold Spray Deposition Process: Fundamentals and Applications, Woodhead Publishing Ltd, Cambridge, 2007

L. Karen, J.K. Taylor, M. Brochu, and B. Jodoin, Cold Spray Application of Metallic/Bio-Ceramic Composite Powders, Thermal Spray 2007: Global Coating Solutions, B. Marple, M. Hyland, Y.-C. Lau, C.J. Li, R.S. Lima, and G. Montavon, Ed., ASM International, Materials Park, 2007,

T. Connolley, P.E. McHugh, and M. Bruzzi, A Review of Deformation and Fatigue of Metals at Small Size Scales, Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct., 2005, 28(12), p 1119-1152

R.V. Marrey, R. Burgermeister, R.B. Grishaber, and R.O. Ritchie, Fatigue and Life Prediction for Cobalt-Chromium Stents: A Fracture Mechanics Analysis, Biomaterials, 2006, 27(9), p 1988-2000

B. Al-Mangour, R. Mongrain, E. Irissou, and S. Yue, Improving the Strength and Corrosion Resistance of 316L Stainless Steel for Biomedical Applications Using Cold Spray, Surf. Coat. Technol., 2013, 216, p 297-307

F. Etave, G. Finet, M. Boivin, J.C. Boyer, G. Rioufol, and G. Thollet, Mechanical Properties of Coronary Stents Determined by Using Finite Element Analysis, J. Biomech., 2001, 34(8), p 1065-1075

S. Garg and P.W. Serruys, Coronary Stents: Current Status, J. Am. Coll. Cardiol., 2010, 56(10 SUPPL.), p S1-S42

G. Mani, M.D. Feldman, D. Patel, and C.M. Agrawal, Coronary Stents: A Materials Perspective, Biomaterials, 2007, 28(9), p 1689-1710

P. Poncin, and J. Proft, Stent Tubing: Understanding the Desired Attributes, Medical Device Materials, S. Shrivastava, Ed., 2003, p 253-259

M. Moravej and D. Mantovani, Biodegradable Metals for Cardiovascular Stent Application: Interests and New Opportunities, Int. J. Mol. Sci., 2011, 12(7), p 4250-4270

D.H. Kohn, Metals in Medical Applications, Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci., 1998, 3(3), p 309-316

X.H. Chen, J. Lu, L. Lu, and K. Lu, Tensile Properties of a Nanocrystalline 316L Austenitic Stainless Steel, Scr. Mater., 2005, 52(10), p 1039-1044

P. Susila, D. Sturm, M. Heilmaier, B.S. Murty, and V. Subramanya Sarma, Microstructural Studies on Nanocrystalline Oxide Dispersion Strengthened Austenitic (Fe-18cr-8ni-2w-0.25y2o3) Alloy Synthesized by High Energy Ball Milling and Vacuum Hot Pressing, J. Mater. Sci., 2010, 45(17), p 4858-4865

C. Borchers, T. Schmidt, F. Gartner, and H. Kreye, High Strain Rate Deformation Microstructures of Stainless Steel 316L by Cold Spraying and Explosive Powder Compaction, Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process., 2008, 90(3), p 517-526

C.J. Li, H.T. Wang, Q. Zhang, G.J. Yang, W.Y. Li, and H.L. Liao, Influence of Spray Materials and Their Surface Oxidation on the Critical Velocity in Cold Spraying, J. Therm. Spray Technol., 2010, 19(1-2), p 95-101

W.Y. Li, H. Liao, G. Douchy, and C. Coddet, Optimal Design of a Cold Spray Nozzle by Numerical Analysis of Particle Velocity and Experimental Validation with 316L Stainless Steel Powder, Mater. Des., 2007, 28(7), p 2129-2137

T. Schmidt, F. Gartner, H. Assadi, and H. Kreye, Development of a Generalized Parameter Window for Cold Spray Deposition, Acta Mater., 2006, 54(3), p 729-742

K. Spencer and M.X. Zhang, Optimisation of Stainless Steel Cold Spray Coatings Using Mixed Particle Size Distributions, Surf. Coat. Technol., 2011, 205(21-22), p 5135-5140

G. Sundararajan, P.S. Phani, A. Jyothirmayi, and R.C. Gundakaram, The Influence of Heat Treatment on the Microstructural, Mechanical and Corrosion Behaviour of Cold Sprayed SS 316L Coatings, J. Mater. Sci., 2009, 44(9), p 2320-2326

X.M. Meng, J.B. Zhang, W. Han, J. Zhao, and Y.L. Liang, Influence of Annealing Treatment on the Microstructure and Mechanical Performance of Cold Sprayed 304 Stainless Steel Coating, Appl. Surf. Sci., 2011, 258(2), p 700-704

W. Wong, E. Irissou, A. Ryabinin, J.-G. Legoux, and S. Yue, Influence of Helium and Nitrogen Gases on the Properties of Cold Gas Dynamic Sprayed Pure Titanium Coatings, J. Therm. Spray Technol., 2011, 20(1), p 213-226

E. Irissou, J.-G. Legoux, B. Arsenault, and C. Moreau, Investigation of Al-Al2O3 Cold Spray Coating Formation and Properties, J. Therm. Spray Technol., 2007, 16(5), p 661-668

“ASTM E8/E8M-09 Standard Test Methods for Tension Testing of Metallic Materials,” E8/E8M-09, ASTM International, p 1-27

M. Matula, L. Hyspecka, M. Svoboda, V. Vodarek, C. Dagbert, J. Galland, Z. Stonawska, and L. Tuma, Intergranular Corrosion of AISI, 316L Steel, Mater. Charact., 2001, 46(2-3), p 203-210

J.K.L. Lai, A Review of Precipitation Behaviour in AISI, Type 316 Stainless Steel, Mater. Sci. Eng., 1983, 61(2), p 101-109

F. Gartner, T. Stoltenhoff, J. Voyer, H. Kreye, S. Riekehr, and M. Kocak, Mechanical Properties of Cold-Sprayed and Thermally Sprayed Copper Coatings, Surf. Coat. Technol., 2006, 200(24), p 6770-6782

Acknowledgments

The cold spray equipment used for this study was partially funded by CFI project number 8246 McGill University (Montreal, Canada) with the support of Cold Gas Technology GmbH, Tecnar Automation Ltd., and Polycontrols Technologies Inc. The authors would like to thank Jean-François Alarie, and Bernard Harvey from the National Research Council Canada (NRC, Boucherville, Canada) for performing the cold spray process. One of the authors, Bandar AL-Mangour, would like to extend his appreciation to the Saudi Basic Industries Corporation, which generously awarded financial support to him.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

AL-Mangour, B., Vo, P., Mongrain, R. et al. Effect of Heat Treatment on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Stainless Steel 316L Coatings Produced by Cold Spray for Biomedical Applications. J Therm Spray Tech 23, 641–652 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11666-013-0053-2

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11666-013-0053-2