Abstract

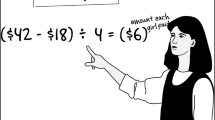

This research focused on how teachers establish and maintain shared understanding with students during classroom mathematics instruction. We studied the micro-level interventions that teachers implement spontaneously as a lesson unfolds, which we call micro-interventions. In particular, we focused on teachers’ micro-interventions around trouble spots, defined as points during the lesson when students display lack of understanding. We investigated how teachers use gestures along with speech in responding to such trouble spots in a corpus of six middle-school mathematics lessons. Trouble spots were a regular occurrence in the lessons (M = 10.2 per lesson). We hypothesized that, in the face of trouble spots, teachers might increase their use of gestures in an effort to re-establish shared understanding with students. Thus, we predicted that teachers would gesture more in turns immediately following trouble spots than in turns immediately preceding trouble spots. This hypothesis was supported with quantitative analyses of teachers’ gesture frequency and gesture rates, and with qualitative analyses of representative cases. Thus, teachers use gestures adaptively in micro-interventions in order to foster common ground when instructional communication breaks down.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Beat gestures that were superimposed on representational gestures were not counted separately, as coders had difficulty identifying these gestures reliably.

References

Alibali, M. W., Heath, D. C., & Myers, H. J. (2001). Effects of visibility between speaker and listener on gesture production: Some gestures are meant to be seen. Journal of Memory and Language, 44, 169–188.

Alibali, M. W., & Nathan, M. J. (2007). Teachers’ gestures as a means of scaffolding students’ understanding: Evidence from an early algebra lesson. In R. Goldman, R. Pea, B. Barron, & S. J. Derry (Eds.), Video research in the learning sciences (pp. 349–365). Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Alibali, M. W., & Nathan, M. J. (2012). Embodiment in mathematics teaching and learning: Evidence from students’ and teachers’ gestures. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 21(2), 247–286.

Alibali, M. W., Nathan, M. J., & Fujimori, Y. (2011). Gestures in the mathematics classroom: What’s the point? In N. Stein & S. Raudenbush (Eds.), Developmental Cognitive Science Goes To School (pp. 219–234). New York: Routledge, Taylor and Francis.

Alibali, M. W., Young, A. G., Crooks, N. M., Yeo, A., Ledesma, I. M., Nathan, M. J., et al. (2012). Students learn more when their teacher has learned to gesture effectively (Submitted).

Arzarello, F. (2006). Semiosis as a multimodal process. In Revista latinoamericana de investigacion en mathematic educativa, numero especial, pp. 267–299.

Arzarello, F., Paola, D., Robutti, O., & Sabena, C. (2009). Gestures as semiotic resources in the mathematics classroom. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 70(2), 97–109.

Barsalou, L. W. (2008). Grounded cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 617–645.

Blake, B., & Pope, T. (2008). Developmental psychology: Incorporating Piaget’s and Vygotsky’s theories in classrooms. Journal of Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives in Education, 1(1), 59–67.

Brintoon, B., & Fujiki, M. (1989). Conversational management with language-impaired children. Rockville: Aspen.

Church, R. B., Ayman-Nolley, S., & Mahootian, S. (2004). The role of gesture in bilingual education: Does gesture enhance learning? International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 7, 303–319.

Church, R. B., Garber, P., & Rogalski, K. (2007). The role of gesture in memory and social communication. Gesture, 7, 137–158.

Clark, H. H. (1996). Using language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Clark, H. H., & Brennan, S. A. (1991). Grounding in communication. In L. B. Resnick, J. M. Levine, & S. D. Teasley (Eds.), Perspectives on socially shared cognition. Washington, DC: APA.

Cook, S. W., Mitchell, Z., & Goldin-Meadow, S. (2007). Gesturing makes learning last. Cognition, 106, 1047–1058.

Cobb, P., Wood, T., & Yackel, E. (1993). Discourse, mathematical thinking and classroom practice. In E. Forman, N. Minick, & C. Stone (Eds.), Contexts for learning: Sociocultural dynamics in children’s development (pp. 91–119). New York: Oxford University Press.

Edwards, L. D. (2009). Gestures and conceptual integration in mathematical talk. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 70, 127–141.

Evans, M. A., Feenstra, E., Ryon, E., & McNeill, D. (2011). A multimodal approach to coding discourse: Collaboration, distributed cognition, and geometric reasoning. Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 6, 253–278.

Flevares, L. M., & Perry, M. (2001). How many do you see? The use of nonspoken representations in first-grade mathematics lessons. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, 330–345.

Glenberg, A. M. (2010). Embodiment as a unifying perspective for psychology. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 1, 586–596.

Golab, J., Lind, C., & Okell, E. (2009). Conversation analysis of repair in interaction with adults who have acquired hearing impairment. In Hearing Care for Adults 2009. Chicago: Phonak.

Goldin-Meadow, S., & Singer, M. A. (2003). From children's hands to adults' ears: Gesture’s role in the learning process. Developmental Psychology, 39, 509–520.

Goldin-Meadow, S., Kim, S., & Singer, M. (1999). What the teachers’ hands tell the students’ minds about math. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91, 720–730.

Goldin-Meadow, S., Wein, D., & Chang, C. (1992). Assessing knowledge through gesture: Using children’s hands to read their minds. Cognition and Instruction, 9, 201–219.

Goodwin, C. (2007). Environmentally coupled gestures. In S. Duncan, J. Cassell, & E. Levy (Eds.), Gesture and the dynamic dimensions of language (pp. 195–212). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Hatano, G., & Inagaki, K. (1991). Sharing cognition through collective comprehension activity. In L. B. Resnick, J. M. Levine, & S. D. Teasley (Eds.), Perspectives on socially shared cognition (pp. 331–348). Washington: APA.

Holler, J., & Stevens, R. (2007). The effect of common ground on how speakers use gesture and speech to represent size information. Journal of Language & Social Psychology, 26, 4–27.

Hostetter, A. B. (2011). When do gestures communicate? A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 137(2), 297–315.

Hostetter, A. B., & Alibali, M. W. (2008). Visible embodiment: Gestures as simulated action. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 15, 495–514.

Hostetter, A. B., & Alibali, M. W. (2010). Language, gesture, action! A test of the gesture as simulated action framework. Journal of Memory and Language, 63, 245–257.

Hostetter, A. B., Bieda, K., Alibali, M. W., Nathan, M. J., & Knuth, E. J. (2006). Don’t just tell them, show them! Teachers can intentionally alter their instructional gestures. In R. Sun (Ed.), Proceedings of the 28th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society (pp. 1523–1528). Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Hurtig, R. (1977). Toward a functional theory of discourse. In R. O. Freedle (Ed.), Discourse production and comprehension. Norwood: Ablex.

Kim, M., Roth, W.-M.,& Thom, J. (2011). Children’s gestures and the embodied knowledge of geometry. International Journal of Science & Mathematics Education, 9(1), 207–238.

Lakoff, G., & Núñez, R. (2001). Where mathematics comes from: How the embodied mind brings mathematics into being. New York: Basic Books.

Marrongelle, K. (2007). The function of graphs and gestures in algorithmatization. Journal of Mathematical Behavior, 26(3), 211–229.

McNeil, N. M., Alibali, M. W., & Evans, J. L. (2000). The role of gesture in children’s comprehension of spoken language: Now they need it, now they don’t. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 24, 131–150.

McNeill, D. (1992). Hand and mind: What gestures reveal about thought. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

McNeill, D. (2010). Gesten der Macht und die Macht der Gesten (gestures of power and the power of gestures). In E. Fischer-Lichte & C. Wulf (Eds.), Gesten, Inszenierung, Aufführung und Praxis (Gesture, Staging, Performance, and Practice). Munich: Wilhelm Fink.

McNeill, D., & Duncan, S. (2000). Growth points in thinking-for-speaking. In D. McNeill (Ed.), Language and gesture (pp. 141–161). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nathan, M. J., & Alibali, M. W. (2011). How gesture use enables intersubjectivity in the classroom. In G. Stam & M. Ishino (Eds.), Integrating gestures: The interdisciplinary nature of gesture (pp. 257–266). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Nathan, M. J., Eilam, B., & Kim, S. (2007). To disagree, we must also agree: How intersubjectivity structures and perpetuates discourse in a mathematics classroom. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 16(4), 525–565.

Nathan, M. J., & Kim, S. (2009). Regulation of teacher elicitations in the mathematics classroom. Cognition and Instruction, 27(2), 91–120.

NCTM. (2000). Principles and standards for school mathematics. Reston: Author.

Nemirovsky, R., Rasmussen, C., Sweeney, G., & Wawro, M. (2012). When the classroom floor becomes the complex plane: Addition and multiplication as ways of bodily navigation. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 21(2), 287–323.

Núñez, R. (2005). Do real numbers really move? Language, thought, and gesture: The embodied cognitive foundations of mathematics. In F. Iida, R. Pfeifer, L. Steels, & Y. Kuniyoshi (Eds.), Embodied artificial intelligence (pp. 54–73). Berlin: Springer.

Paulus, T. M. (2009). Online but off-topic: Negotiating common ground in small learning groups. Instructional Science, 37, 227–245.

Radford, L., Edwards, L., & Arzarello, F. (2009). Introduction: beyond words. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 70, 91–95.

Rasmussen, C., Stephan, M., & Allen, K. (2004). Classroom mathematical practices and gesturing. Journal of Mathematical Behavior, 23, 301–324.

Richland, L. E., Zur, O., & Holyoak, K. J. (2007). Cognitive supports for analogies in the mathematics classroom. Science, 316, 1128–1129.

Roth, W.-M. (2002). Gestures: Their role in teaching and learning. Review of Educational Research, 71, 365–392.

Schegloff, E., Jefferson, G., & Sacks, H. (1977). The preference for self-correction in the organisation of repair in conversation. Language, 53, 361–382.

Schleppenbach, M., Flevares, L. M., Sims, L. M., & Perry, M. (2007). Teachers’ responses to student mistakes in Chinese and U.S. mathematics classrooms. The Elementary School Journal, 108(2), 131–147.

Schoenfeld, A. H. (1998). Toward a theory of teaching-in-context. Issues in Education: Contributions from Cognitive Psychology, 4, 1–94.

Seedhouse, P. (2004). The interactional architecture of the language classroom: A conversation analysis perspective. Malden: Blackwell.

Sfard, A. (2009). What’s all the fuss about gestures? A commentary. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 70(2), 191–200.

Shapiro, L. (2011). Embodied cognition. New York: Routledge.

Sidnell, J. (2010). Conversation analysis: An introduction. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

Singer, M. A., & Goldin-Meadow, S. (2005). Children learn when their teacher’s gestures and speech differ. Psychological Science, 16, 85–89.

Singer, M. A., Radinsky, J., & Goldman, S. R. (2008). The role of gesture in meaning construction. Discourse Processes, 45, 365–386.

Valenzeno, L., Alibali, M. W., & Klatzky, R. L. (2003). Teachers’ gestures facilitate students’ learning: A lesson in symmetry. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 28, 187–204.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Trans.). Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Wilson, M. (2002). Six views of embodied cognition. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 9, 625–636.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant # R305H060097 from the U. S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences (Alibali, PI). All opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and not the U. S. Department of Education. We thank Maia Ledesma, Kristen Bieda, and Elise Lockwood for their contributions to this research. Most of all, we thank the teachers and students who opened their classrooms to us and allowed us to videotape their instruction.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alibali, M.W., Nathan, M.J., Church, R.B. et al. Teachers’ gestures and speech in mathematics lessons: forging common ground by resolving trouble spots. ZDM Mathematics Education 45, 425–440 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-012-0476-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-012-0476-0