Abstract

This article theorizes about how individual factors and network effects interact with each other in ways relevant to the study of networks generally, but in particular of criminal networks. In modern network analysis, careful technical descriptions that involve important graph-theory measures are entirely sensible, but they often ignore specific details about the individuals within the network. For study of a human social system, to ignore qualities of the actors is to risk an incomplete, possibly spurious, explanation, so individual-level factors may be important for a more complete understanding of the system. In covert and criminal networks, actors have motivations to keep some activities from public view, so it is impossible to understand such networks without appreciating at least that individual-level intention. This article describes five different levels of effects, both individual and relational, relevant to network-based social systems, and explains how these effects may interact. Important implications for the study of criminal networks include the formation of trust within networks, the exercise of control, and the identification of network brokers. A richer description of individual action within a complex social system will require better knowledge about how personality, social identity and other psychological factors are distinct from, and yet may interact with, self organizing network processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Baker W, Faulkner R (1993) The social organization of conspiracy: illegal networks in the heavy electrical equipment industry. Am Sociol Rev 58:837–860. doi:10.2307/2095954

Barabási A-L, Albert R (1999) Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science 286:509–512. doi:10.1126/science.286.5439.509

Boissevain J (1974) Friends of friends: networks, manipulators and coalitions. Basil Blackwell, Oxford, UK

Borgatti S, Foster P (2003) The network paradigm in organizational research: a review and typology. J Manage 29:991–1013

Brass D, Galaskiewicz J, Greve H, Tsai W (2004) Taking stock of networks and organizations: a multilevel perspective. Acad Manage J 47:795–817

Burt RS (1987) Social contagion and innovation: cohesion versus structural equivalence. Am J Sociol 92:205–211. doi:10.1086/228667

Burt RS (1992) Structural holes: the social structure of competition. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Burt RS, Jannotta JE, Mahoney JT (1998) Personality correlates of structural holes. Soc Networks 20:63–87. doi:10.1016/S0378-8733(97)00005-1

Butts CT (2008) Social network analysis: a methodological introduction. Asian J Soc Psychol 11:13–41. doi:10.1111/j.1467-839X.2007.00241.x

Byrne D (1997) An overview (and underview) of research and theory within the attraction paradigm. J Soc Pers Relat 14:417–431. doi:10.1177/0265407597143008

Cartwright D, Harary F (1956) Structural balance: a generalization of Heider’s theory. Psychol Rev 63:277–292. doi:10.1037/h0046049

Chattoe E, Hamill H (2005) It’s not who you know–It’s what you know about people you don’t know that counts. Br J Criminol 45:860–876. doi:10.1093/bjc/azi051

Christakis N, Fowler J (2007) The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med 357:370–379. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa066082

Coles N (2001) It’s not what you know–it’s who you know that counts: analysing serious crime groups as social networks. Br J Criminol 41:580–594. doi:10.1093/bjc/41.4.580

Copeland, M., Reynolds, K., & Burton, J. (2008) Social identity, status characteristics and social identity: predictors of advice-seeking in a manufacturing facility. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 11, 75-87

Davis JA (1970) Clustering and hierarchy in interpersonal relations: testing two theoretical models in 742 sociograms. Am Sociol Rev 35:843–852. doi:10.2307/2093295

Doreian P, Batalgelj V, Ferligoj A (2005) Generalized blockmodeling. Cambridge University Press

Emirbayer M, Goodwin J (1994) Network Analysis, Culture, and the Problem of Agency. Am J Sociol 99:1411–1454. doi:10.1086/230450

Ennett ST, Bauman KE (1993) Peer group structure and adolescent cigarette smoking: a social network analysis. J Health Soc Behav 34:226–236. doi:10.2307/2137204

Freeman L (1979) Centrality in social networks: conceptual clarification. Soc Networks 1:223–258

Friedkin NE (1998) A structural theory of social influence. Cambridge University Press, NY

Gonzalez-Roma V, Peiro J, Lloret S, Zornoza A (1999) The validity of collective climates. J Occup Organ Psychol 72:25–40. doi:10.1348/096317999166473

Granovetter M (1973) The strength of weak ties. Am J Sociol 81:1287–1303. doi:10.1086/226224

Heider F (1946) Attitudes and cognitive organization. J Psychol 21:107–112

Jackson M (2005) A survey of models of network formation: stability and efficiency. In: Demange G, Wooders M (eds) Group formation in economics: networks, clubs and coalitions. Cambridge University Press, New York

Kadushin C (2002) The motivational foundation of social networks. Soc Networks 24:77–91. doi:10.1016/S0378-8733(01)00052-1

Kalish Y (2008) Bridging in social networks: who are they people in structural holes and why are they there? Asian J Soc Psychol 11:53–66. doi:10.1111/j.1467-839X.2007.00243.x

Kalish Y, Robins GL (2006) Psychological predispositions and network structure: the relationship between individual predispositions, structural holes and network closure. Soc Networks 28(1):56–84. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2005.04.004

Klerks P (2001) The network paradigm applied to criminal organizations: theoretical nitpicking or a relevant doctrine for investigators? Recent developments in the Netherlands. Connections 24:53–65

Kozlowski SWJ, Klein KJ (2000). A multilevel approach to theory and research in organizations: contextual, temporal and emergent processes. In Klein & Kozlowski (Eds), Multi-level theory, research and methods in organizations. (pp 3- 90)

Krackhardt D (1992) The strength of strong ties. In: Nohria N, Eccles RG (eds) Networks and organizations: structure, form and action. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA, pp 216–239

Leenders RTAJ (1997) Longitudinal behavior of network structure and actor attributes: modeling interdependence of contagion and selection. In: Doreian P, Stokman FN (eds) Evolution of Social Networks. Gordon & Breach, Amsterdam, pp 165–184

Lewis J (2005) Health policy and politics: networks, ideas and power. IP Communications, Melbourne, Australia

Lomi A, Lusher D, Pattison P, Robins G (2007) Inter-organizational hierarchies, social networks, and identities in multi-unit organizations. American Sociological Association Annual Meeting, New York August 2007

Lusher D, Robins G Hegemonic and other masculinities in local social contexts. Men Masculinities (in press)

Mason W, Conrey F, Smith E (2007) Situating social influence processes: dynamic, multidirectional flows of influence within social networks. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 11:279–300. doi:10.1177/1088868307301032

McIllwain JS (1999) Organized crime: a social network approach. Crime Law Soc Change 32:301–323. doi:10.1023/A:1008354713842

McFarland D, Pals H (2005) Motives and contexts for identity change: a case for network effects. Soc Psychol Q 68:289–315

McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Cook J (2001) Birds of a feather: homophily in social networks. Annu Rev Sociol 27:415–444. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415

Mehra A, Kilduff M, Brass DJ (2001) The social networks of high and low self-monitors: implications for workplace performance. Adm Sci Q 46:121–146. doi:10.2307/2667127

Milward HB, Raab J (2006) Dark networks as organizational problems: elements of a theory. Int Public Manage J 9:333–360. doi:10.1080/10967490600899747

Morris M (2004) Network epidemiology. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

Morselli P, Petit K (2007) Law-enforcement disruption of a drug importation network. Glob Crime 8:109–130. doi:10.1080/17440570701362208

Morselli C, Roy J (2008) Brokerage qualifications in ringing operations. Criminology 46(1):71–98

Morselli C, Tremblay P (2004) Criminal achievement, offender networks and the benefits of low self-control. Criminology 42:773–804. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2004.tb00536.x

Morselli C, Giguère C, Petit K (2007) The efficiency/security trade-off in criminal networks. Soc Networks 29:143–153. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2006.05.001

Newman MEJ, Park J (2003) Why social networks are different from other types of networks. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys 68:036122

Pattison PE, Robins GL, Kashima Y (2008) Psychology of social networks. In: Blume L, Durlauf S (eds) The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd edn. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, Hampshire

Putnam R (2000) Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster, New York

Raab J, Milward HB (2003) Dark networks as problems. J Public Adm Res Theory 13:413–439. doi:10.1093/jopart/mug029

Rentsch JR (1990) Climate and culture: Interaction and qualitative differences in organizational meanings. J Appl Psychol 75:668–681. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.75.6.668

Robins G, Kashima Y (2008) Social psychology and social networks. Asian J Soc Psychol 11:1–12. doi:10.1111/j.1467-839X.2007.00240.x

Robins GL, Pattison P (2001) Random graph models for temporal processes in social networks. J Math Sociol 25:5–41

Robins GL, Elliott P, Pattison P (2001a) Network models for social selection processes. Soc Networks 23:1–30. doi:10.1016/S0378-8733(01)00029-6

Robins GL, Pattison P, Elliott P (2001b) Network models for social influence processes. Psychometrika 66:161–190. doi:10.1007/BF02294834

Robins G, Pattison P, Kalish Y, Lusher D (2007) An introduction to exponential random graph (p*) models for social networks. Soc Networks 29:173–191. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2006.08.002

Simmel G (1908) Soziologie, Untersuchungen uber die formen der vergesellschaftung. In: Wolff KH (ed) The sociology of Georg Simmel. Free Press, New York, pp 87–408

Skog O (1986) The long waves of alcohol consumption: a social network perspective on cultural change. Soc Networks 8:1–32. doi:10.1016/S0378-8733(86)80013-2

Snijders T, Steglich C, Schweinberger M (2006a) Modeling the co-evolution of networks and behavior. In: van Montfort K, Oud H, Satorra A (eds) Longitudinal models in the behavioral and related sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ

Snijders TAB, Pattison P, Robins GL, Handcock M (2006b) New specifications for exponential random graph models. Sociol Methodol 36:99–153. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9531.2006.00176.x

Sparrow M (1991) The application of network analysis to criminal intelligence: an assessment of the prospects. Soc Networks 13:251–274. doi:10.1016/0378-8733(91)90008-H

Tajfel H, Billig MG, Bundy RP, Flament C (1971) Social categorization and intergroup behavior. Eur J Soc Psychol 1:149–178. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2420010202

Turner JC, Hogg MA, Oakes PJ, Wetherell MS (1987) Rediscovering the social group: a self-categorization theory. Basil Blackwell, Oxford

Varese F (2008) The structure of criminal connections: the Russian-Italian mafia network. Paper presented at the 7th Blankensee colloquium, Human capital and social capital in criminal networks. Institute for Advanced Study, Berlin 28 February -2 March 2008

von Lampe K, Johansen PO (2004) Organized crime and trust: on the conceptualization and empirical relevance of trust in the context of criminal networks. Glob Crime 6:159–184. doi:10.1080/17440570500096734

White HC, Boorman SA, Breiger RL (1976) Social structure from multiple networks: I. Blockmodels of roles and positions. Am J Sociol 87:517–547. doi:10.1086/227495

Acknowledgements

An early version of this paper was presented at the 7th Blankensee colloquium in Berlin in February/March 2008. The author would like to thank the organisers of the colloquium and colloquium participants for helpful discussions and feedback. I would also like to thank Sean Bergin for assistance with the paper, and reviewers who provided valuable suggestions for improvement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Glossary of some common network terms used in this article

Appendix: Glossary of some common network terms used in this article

Actor: typically, an individual who “acts” within a social environment; more generally, a social entity that comprises the nodes of a network. In a criminal network, the actors typically are the criminals.

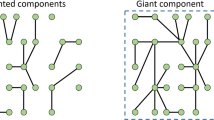

Broker: A network broker connects otherwise disconnected parts of the network. In a criminal communication network, an intermediary between two groups who do not otherwise communicate is a network broker. Brokers occupy structural holes, the “gaps” in the network where certain parts of the network are disconnected.

Centrality of an actor: The “importance” of an actor to a network. There are various types of centralities, two of which are degree centrality (with the most central actors being those with the highest degrees) and betweenness centrality (where the most central actors are those who keep the network connected). In a criminal communication network, criminals with the highest degree centrality are those who have the most communication partners, whereas those who have the highest betweenness centrality are those whose absence would most likely disconnect communications across the network.

Clique: a subset of actors, all of whom are tied to each other.

Connected: Two actors are connected if there is a path from one to the other. A network is disconnected when some actors are not connected to other actors.

Degree: In a nondirected network, the degree of an actor is the number of ties in which that actor is involved; in a directed network, the indegree of the actor is the number of ties received, and the outdegree, the number of ties sent. In a nondirected criminal network relating to communication, the degree of an actor is the number of other criminals with whom the actor communicates. In a criminal trust network, the indegree of an actor represents popularity in terms of how many others trust that actor, whereas the outdegree represents activity (sometimes, termed expansiveness) in the sense of how many others the actor trusts.

Degree distribution: The distribution across the whole network of the number of actors with given degrees. In a criminal communication network that was highly centralized, with some criminals having many communication partners and many with few communication partners, the distribution would be both skewed and bimodal, with a few high degree nodes, and many low degree nodes. For directed networks, there are both indegree and outdegree distributions.

Density of a network is the proportion of observed ties to possible ties.

Directed/nondirected network: A network may be directed in that an actor expresses (or sends) a tie towards another actor (who receives it), or nondirected (or undirected) where there is no directionality in the tie. In criminal network studies, examples of nondirected networks might include alliance (i.e. two criminals might be allied to each other); examples of directed networks might include threat (i.e. one criminal might threaten another.)

Dyad: a pair of actors and the relations between them.

Geodesic: The shortest path between two actors is a geodesic, the length of which is the geodesic distance (taken to be infinite if the pair of actors is disconnected, i.e. without a path between them.) In a criminal communication network, the geodesic distance between two criminals i and j is the smallest number of communications by which i can communicate with j. If i and j are tied, then this distance is 1; if not, but they can communicate through one intermediary k, then the geodesic distance is 2.

Geodesic distribution: The distribution across the whole network of geodesic distances.

Graph: a mathematical object used to represent a network, comprising a set of nodes or vertices, representing actors, and edges (lines) representing ties. A graph can be drawn as a network visualization.

Network: comprises a set of actors (individuals) and a set of relational ties among them.

Path is a sequence of connected ties from one actor to another; the length of the path is the number of ties in it.

Reciprocity: In a directed network, a reciprocated (or mutual) tie occurs when ties both from i to j and from j to i are present in the network.

Relational tie: a social connection between actors. Different types of relational ties express different types of social connections (e.g. advice, communication, trust, acquaintanceship, friendship, hatred.)

Structural hole: See broker.

Triangle: a clique of three actors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Robins, G. Understanding individual behaviors within covert networks: the interplay of individual qualities, psychological predispositions, and network effects. Trends Organ Crim 12, 166–187 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-008-9059-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-008-9059-4