Abstract

This study applies the Lindenmayer system based on fractal theory to generate synthetic fracture networks in hydraulically fractured wells. The applied flow model is based on complex analysis methods, which can quantify the flow near the fractures, and being gridless, is computationally faster than traditional discrete volume simulations. The representation of hydraulic fractures as fractals is a more realistic representation than planar bi-wing fractures used in most reservoir models. Fluid withdrawal from the reservoir with evenly spaced hydraulic fractures may leave dead zones between planar fractures. Complex fractal networks will drain the reservoir matrix more effectively, due to the mitigation of stagnation flow zones. The flow velocities, pressure response, and drained rock volume (DRV) are visualized for a variety of fractal fracture networks in a single-fracture treatment stage. The major advancement of this study is the improved representation of hydraulic fractures as complex fractals rather than restricting to planar fracture geometries. Our models indicate that when the complexity of hydraulic fracture networks increases, this will suppress the occurrence of dead flow zones. In order to increase the DRV and improve ultimate recovery, our flow models suggest that fracture treatment programs must find ways to create more complex fracture networks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The massive shift in US oil and gas production, after the Millennium turn, from conventional to unconventional reservoirs, has seen the hydraulic fracturing of production wells become a crucial aspect of completion engineering. The productivity of shale wells is now primarily based on how effectively hydraulic fractures help to provide new pathways for flow toward the wells from the reservoir matrix with ultra-low permeability. A proper understanding of the creation of hydraulic fractures and modeling of fluid flow near these fractures is needed for improvement in both the early well productivity and the ultimate recovery factor. The engineering of hydraulic fractures in unconventional hydrocarbon plays is a rapidly evolving art. Industry has moved to reduce fracture spacing from over 100 ft in 2010, to 50 ft in 2014, and less than 20 ft in 2018. The fracture spacing is designed using estimations of geomechanical rock properties from pilot wells in combination with fracture propagation models.

The earliest attempts to compare hydraulic fracture patterns may be traced back to Warpinski et al. (1994), but today there is still no consensus regarding the relative merits of the various fracture propagation modeling platforms. The American Rock Mechanics Association (ARMA) has recently initiated seven benchmark tests for 20 participating models (Han 2017) with the intent to showcase recognized physics of hydraulic fracturing. Most platforms for modeling hydraulic fracture propagation are based on assumed homogeneous rock properties, which therefore uniquely favor the formation of planar, sub-parallel hydraulic fractures (Parsegov et al. 2018).

Although current fracture diagnostics can rarely resolve the detailed nature of the fractures created during fracture treatment of unconventional hydrocarbon wells (Grechka et al. 2017), recent empirical evidence suggests that deviations from planar fracture geometry may exist. Physical evidence from cores that were sampled from a hydraulically fractured rock volume indicates that the generated fracture density far exceeds the number of perforation clusters (Raterman et al. 2017). The creation of fracture complexity in terms of deflection, offset, and branching is possible at bedding surfaces and other naturally occurring heterogeneities, with preexisting natural fractures not appearing necessary for the creation of complex, distributed fracture systems. In fact, this finding is not entirely new. Work by Huang and Kim (1993) from mineback and laboratory experiments showed that the common notion that hydraulic fractures are planar in nature and assumed to propagate linearly perpendicularly to the minimum stress in simplified geomechanical models is not always correct. Clearly, empirical evidence suggests that fracture treatment may form fracture networks with branching fractal dimensions initiating from the perforation points (Fig. 1b), rather than planar hydraulic fractures (Fig. 1a). Thus, the practice of representing hydraulic fractures as single-planar, bi-wing cracks in the subsurface may be an overly simplistic representation of what in reality are more complex, fractal structures.

The likelihood of complex fracture networks being created by the fracture treatment process (rather than mutually sub-parallel planar fractures) is further supported by evidence from microseismic monitoring (Fisher et al. 2002; Maxwell et al. 2002). In fact, most microseismic clouds generated during fracturing jobs show a poor correlation with the assumed planar, sub-parallel fractures. Therefore, we assume that the creation of complex hydraulic fracture networks may be more representative for many fractured or treated wells, especially those that possess a network of natural fractures due to stress regimes varying over geological time. Such conditions are typical of most unconventional shale plays under exploration and development. Consequently, the use of planar hydraulic fractures for modeling reservoir depletion may not always appropriately account for the actual reservoir attributes. The subsequent use of such over-simplified planar fracture geometries in flow models leads to unreliable calculations of important reservoir attributes such as the drained rock volume (DRV) and flaws in the associated pressure response.

Current fracture representation methods that try to capture fracture complexity include discrete fracture network models and the unconventional fracture model (Weng et al. 2011; Zhou et al. 2012) and are reviewed in Sect. 3.1. These established fracture geometry models use block centered grids typically coupled with finite-difference discretization flow models, including compositional flow models to simulate reservoir performance (Yu et al. 2017). The drawback of these finite-difference schemes is that they can be computationally intensive due to the necessity of fine meshing, especially at the fracture intersections. Other methods to model flow in fractured porous media include semianalytical models to simulate and analyze the pressure change for complex well interference systems (Yu et al. 2016). The suitability of the dual-porosity flow model (Warren and Root 1963) for low permeability reservoirs has been questioned (Cai et al. 2015). Further work has led to the development of triple porosity models to model flow in fractured reservoirs (Sang et al. 2016). Zhou et al. (2012) proposed a semianalytical solution for flow in a complex hydraulic fracture network model, which combined an analytical reservoir solution with a numerical solution on discretized fracture panels. The present study applies the analytical CAM flow model (Weijermars et al. 2016, 2017a, b, 2018), which is computationally efficient, while being able to accurately model the flow near fractal fractures such as those observed in field tests (Raterman et al. 2017).

Planar, sub-parallel hydraulic fractures with a certain spacing will develop dead flow zones between them where no fluid can be moved due to the occurrence of stagnation points surrounded by infinitely slow flow regions in their vicinity (Fig. 2a). Such dead zones suppress well productivity. These may be remedied by plugging prior perforations and re-fracking into the dead flow zones by placing new perforations midway between the legacy perf zones after prior production wanes (Fig. 2b). However, the existence of dead zones is entirely premised upon the assumption that hydraulic fractures are planar and sub-parallel (Weijermars et al. 2017a, b, 2018).

The flow analysis in this study uses branched fractals for describing the complex fracture networks that are present in the subsurface. A variety of branched fractal fracture networks are imported into a drainage model based on complex analysis methods (CAM) to determine the flow response and pressure changes in the reservoir, for a given fracture geometry and fracture surface area. The major effect observed due to increasing fractal nature and branching of the fracture network (as outlined later in this study) is that the extent of dead zones between hydraulic fracture stages is suppressed. Instead, a more diffuse network of fractures drains the matrix between the fracture initiation points spaced by the perforation zones. Depending on the geometry of hydraulic fractures, an otherwise non-fractured matrix with negligible spatial variation in permeability can be drained more or less effectively. Future work will need to determine when hydraulic fractures will develop as fractal networks. While the jury is still out on the prominent geometry of hydraulic fractures (planar vs. fractal), the models developed in the present study consider the effect on drained rock volume in a systematic investigation of hydraulic fracture geometry ranging from planar to multi-branched, higher-order fractals. The present study breaks new ground by modeling the flow around fractal fracture networks in porous media. The results have implications for fracture treatment designs required to maximize the drained rock volume.

2 Natural examples of hydraulic fractures

In addition to the cited examples of hydraulic fractures branching into closely spaced fracture networks (Raterman et al. 2017; Huang and Kim 1993), manifestations of bifurcating fracture networks are commonly known from surface outcrops of hydraulic fractures formed by natural processes. For example, hydrothermal veins invaded and hydraulically fractured Proterozoic rocks from the Aravalli Supergroup in the state of Rajasthan, India (Kilaru et al. 2013; McKenzie et al. 2013; Pradhan et al. 2012). These hydraulic fractures formed under high fluid pressures deeper in the crust before being exhumed by tectonic uplift and erosion. Polished slabs containing the naturally created hydraulic fracture networks in Bidasar ophiolites are shown in Fig. 3a. These rocks are exploited as facing stones and quarried near the villages of Bidasar-Charwas, Churu district (Fig. 3b). The quarries are confined to a 0.5-km-wide and 2.5–3.5-km-long belt of open pits dug below the desert plain. The rock in these pits has been described as the Bidasar ophiolite suite (Mukhopadhyay and Bhattacharya 2009).

a Examples of rock slabs from Bidasar with bifurcating, hydraulic injection veins. Image dimensions about 1 square meter (courtesy Dewan Group). b Satellite image of quarry near Bidasar, Rajasthan, India (roads for scale). North is down in the above image (Google Earth composite of December 16, 2015)

The precise natural pressure responsible for the injection of the hydraulic veins is unknown, but the pressure has exceeded the strength of the rock and was large enough to open the fractures at several km burial depth, thus being in the order of 100 MPa. The fluid was injected into the fractures as well as into a pervasive system of microcracks connected to the main fractures. Based upon the splaying of the fractures, one may reconstruct the provenance of the fracture propagation (van Harmelen and Weijermars 2018). Local heterogeneities in elastic properties may create conditions favoring the nucleation of fracture bifurcation points. More work is needed to determine the critical conditions required for creating fractal fracture networks in hydraulic fracture treatment programs.

Slabs like those shown in Fig. 3a may serve as a natural analog for flow into hydraulic fractures in shale reservoirs, with the limitation that shale may have different elastic moduli, different petrophysics, grain sizes and most crucially, the fracture aperture width from hydraulic fracturing which is smaller than that in our natural analog presented here. Hydraulic fracture apertures in shale reservoirs are thought to be in the range of 1–5 mm with the majority of created fracture apertures being less than 2 mm (Gale et al. 2014; Zolfaghari et al. 2016; Arshadi et al. 2017). Natural fracture networks created in the rocks of Bidasar due to hydrothermal activity in the earth’s crust bears similarity to man-made hydraulic fracture networks that require the use of high pressure fluids and proppants by fleets of pumps and trucks.

We contend that the injection patterns of hydrothermal veins exposed in natural outcrops and in quarries (of rocks exhumed by tectonic processes and subsequent erosion) provide a useful analog for hydraulic fracture networks created when fluid injection is applied to hydrocarbon wells. Figure 4a, b shows an analysis of the principal hydraulic fractures in a rock slab from Bidasar. The corresponding flow front through the main fractures and matrix is modeled in Fig. 4c, d. The simulation does not account for the creation of the fractures, but instead assumes that these have already developed and are subsequently flushed by the hydrothermal injection fluid. For details, see a prior study from our research group (van Harmelen and Weijermars 2018).

Orthogonal photograph of polished rock slab with injection veins. a Filled fracture veins with interpreted directions of the original largest (σ1) and intermediate (σ2) principal stress axes. Major veins open first normal to σ1 and then normal to σ2, which likely swapped with σ1 after hydraulic loading of the main veins. b Interpreted principal fracture network (yellow lines). c, d Fluids take by matrix and fractures in model assuming low permeability contrast (c), and high permeability contrast (d). Matrix blocks between the fractures in case d take less fluids than in case c. Rainbow colors give time of flight contours, and fluid injection is from the top. Flow lines are given by magenta streamlines.

3 Fractures and fractal theory

3.1 Prior models of complex hydraulic fractures

3.1.1 Fracture propagation and fracture flow models

Various attempts have been made by researchers to develop new models to better represent complex hydraulic fracture network systems, in both geomechanical fracture propagation models and in production forecasting based on flow models in fractured reservoirs. For example, the geomechanical unconventional fracture model (UFM) was developed to simulate the propagation of complex fractures in formations with preexisting natural fractures (Weng et al. 2011). The UFM simulates the propagation, deformation, and fluid flow in a complex network of fractures. The model seeks to solve a system of equations governing parameters such as fracture deformation, height growth, fluid flow, and proppant transport, while considering the effect of natural fractures by using an analytical crossing model. The Wiremesh model consists of a fracture network with two orthogonal sets of parallel and uniformly spaced fractures (Xu et al. 2010; Meyer and Bazan 2011). Given fracture spacing, mechanical properties of the formation layers and pumping parameters, this shale fracturing simulator can be used to predict the growth of the hydraulic fracture network. Benefits of the Wiremesh model come in the form of increased surface area of the fracture network and mechanical interaction of fractures but are still only an approximation of the network’s complexity. Limitations of this model include not being able to directly link preexisting natural fractures to the hydraulic fracture network with regard to the fracture spacing used and that the network geometry is assumed to be elliptical in shape and thus symmetric. These assumptions do not always fit with fracture geometry indicated by microseismic data. Alternative modeling attempts sought to create a complex fracture network by finding a full solution to the coupled elasticity and fluid flow equations using 2D plane strain conditions (Zhang et al. 2007). Other studies presented a complex fracture network capable of predicting the interaction of hydraulic fractures with natural fractures but did not consider fluid flow and proppant transport (Olson and Taleghani 2009).

Flow models of fractured reservoirs have also advanced by upscaling a discrete fracture network (DFN) model into a dual-porosity reservoir model or by enhancing the permeability of stimulated reservoir areas (Zhou et al. 2012). The fundamental discrete fracture network (DFN) solution methodology is based on satisfying continuity, mass conservation, constitutive relationships, and momentum equations (Meyer and Bazan 2011). For fracture representation in this method, each fracture panel had to be manually input with specific fracture parameters thus requiring prior knowledge of hydraulic fracture orientation. The model also assumes the intersection of individual planar fractures to create the complex fracture network with drained area represented by pressure depletion plots. These DFN are created using stochastic simulations based on probabilistic density functions of geometric parameters of fracture sets relating to fracture density, location, orientation and sizes based on measurements from field outcrops or borehole images. DFN requires an extremely fine grid at the scale of the fractures leading to complicated gridding and for multi-stage wells with large fracture numbers is very computationally expensive.

Recent advancements with DFN have now led to the embedded discrete fracture model (EDFM). EDFM allows for complex fractures to be implemented in conventionally structured matrix grids without using local grid refinement (Yu and Sepehrnoori 2018). EDFM can be thought of as a hybrid approach where the dual-porosity model is used for the smaller- and medium-size fractures, and the DFN is used to model larger fractures (Li and Lee 2008). Advantages of EDFM include the use of a structured grid to represent the matrix and fractures. EDFM was initially used for planar 2D cases but has developed to model in 3D (Moinfar et al. 2014). Though EDFM has overcome some of the problems of the traditional DFM method, it can still be computationally expensive in complexly fractured reservoirs.

3.1.2 Fracture geometry models

Beyond the modeling attempts outlined above to recreate and describe complex fracture networks, work has been done by various authors to characterize the created fracture complexity based on field data. Zolfaghari et al. (2016) proposed the use of flowback salinity data to help characterize the fracture network complexity. The shape of the flowback curves is used to define the aperture size distribution (ASD) for a particular well. A narrow ASD is correlated with a simple fracture network, while a wider ASD is believed to match a fracture network that is more dendritic and complex in nature. Zolfaghari et al. (2017) looked at correlating total ions produced from chemical flowback to estimate fracture surface area for two wells that was validated against rate transient analysis (RTA) values. Based on these results, the authors postulated that greater production from one well was due to the larger fracture area calculated. This larger fracture area was attributed to a more complex fracture network in the subsurface, but there was no indication of potential fracture geometry. Another attempt to characterize fracture complexity utilizes tracer flowback data. Li et al. (2016) made use of tracer flowback data to characterize fracture morphology into three general categories. Based on the tracer breakthrough curve (BTC) the hydraulic fractures are roughly classified as microfractures, large fractures, and their mix. These methods allow for qualitative descriptions of the subsurface fracture network but do not allow for quantitative description in terms of surface area of the complex fracture network in contact with the reservoir matrix or fracture network geometry.

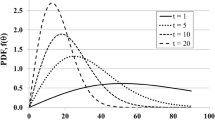

The majority of fracture flow methods attempt to introduce discrete fractures to model explicitly the elastic fracture propagation, subsequent flow and evacuation of fluid from the reservoir. The importance of accounting for fracture network complexity is apparent from production and pressure transient responses (Jones et al. 2013). Properly modeling the complexity of the fracture network is crucial for accurate history matching in these reservoirs. In addition to the discrete fracture models based on geomechanical failure modes, another potential approach to model fracture complexity uses fractal geometry. Fractals have long been used to model naturally occurring phenomena including petroleum reservoir and subsurface properties and equations (Berta et al. 1994; Cossio et al. 2012). Early work by Katz and Thompson (1985) and Pandey et al. (1987) showed that fracture propagation in nature was not irregular and could be represented by various fractal models. Building forward on this work Al-Obaidy et al. (2014) and Wang et al. (2015) approached the fracture network problem by creating branched fractal models to capture fracture network complexity.

3.2 Fractal theory

Fractal theory was first put forth by Mandelbrot (1979) as “a workable geometric middle ground between the excessive geometric order of Euclid and the geometric chaos of general mathematics”. A fractal was defined by Mandelbrot as a rough or fragmented geometric shape that can be split into parts each of which is a reduced-size copy of the whole. For an object to be termed a fractal, it must possess some non-integer (fractal) dimension (Frame et al. 2012). If this fractal dimension is an integer, we can obtain normal Euclidean geometry such as lines, triangles and regular polygons. Cossio et al. (2012) put into simple terms that a property of a given system can be termed a fractal if its seemingly chaotic, and unpredictable behavior with respect to time and space can be captured in a simple power-law equation. One of the basic principles underlying fractal geometry is the concept of self-similarity at various levels. If one zooms in on the represented object, a natural repetition of patterns and properties can be observed.

The abundance of fractals in our natural environment ranges from the fractal nature of coastlines to the growth and bifurcation of trees and plants. The use of fractals allows one to make mathematical sense from seemingly random and chaotic processes. Early use of fractals in petroleum engineering began with the work of Katz and Thompson (1985) to represent pore spaces in sandstone cores. The use of fractal theory to represent the pore space was verified by its accurate prediction of the core porosity. We now extend this approach of fractals to model complex hydraulic fracture networks in a reservoir with assumed parameters.

One approach in the fractal theory is to create a fracture network model by using the fractal addition of the Lindenmayer system (Wang et al. 2017). The Lindenmayer system (L-system) is widely used to describe the growth of plants which can be seen to be bifurcating in nature as well as being fractal at some scale. The L-system is a rewriting system that defines a complex object by replacing parts of the initial object according to given rewriting rules which simulate development rules and topological structures well (Lindenmayer 1968; Han 2007). Wang et al. (2017) introduced the L-system into fracture characterization because a fracture has similar development rules to trees. Four key parameters are used to control the generation of the fracture network, and these parameters influence the performance of production wells (Wang et al. 2018):

-

1.

Fractal distance (d) controls the extending distance of the fractal fractions, (can be thought of as a basic repeating pattern) and closely relates to the half-length of the fractures created.

-

2.

Deviation angle (α) controls the orientation of the fracture branching once deviation from the base fracture pattern occurs and relates to the area of the stimulated reservoir.

-

3.

Number of iterations (i) controls the growth complexity of the fracture network or in other words fracture network density. This parameter relates to the multi-level feature of the fractal branches; during each iteration, the fractal fractures will branch from the original nodes following the given generating rules to construct that part of the network.

-

4.

Growth of the bifurcation of the fractures and irregular propagation mode of a complex fracture network are subject to fractal rules, which are an implicit means to account for geomechanical heterogeneities (Wang et al. 2015, 2017, 2018).

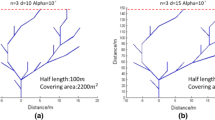

The branching fractal model used in our study makes use of a simple L-system growth rule, which along with the fractal distance parameter controls the branched hydraulic fracture network’s half-length, the deviation angle controls the branched fracture network width span, and the iteration number controls the branching complexity or density. Though the fracture geometry created using the L-system is seemingly random, we use the branching of the hydraulic fracture in our models to capture and replicate the physical evidence seen in cores recovered from the Hydraulic Fracturing Test Site (HFTS). These cores show that hydraulic fractures “diverge with a projected line of intersection, or branch line, just out of the core” (Raterman et al. 2017). We acknowledge that due to uncertainty in the subsurface, there are infinite possibilities that can be modeled by changing parameters such as branching angle, fracture length, and iteration number. Our current model uses branching angles and other parameters (given in Table 1) that generate a fractal network span and half-length that matches commonly observed values from fracture propagation modeling and microseismic data.

4 Flow models

4.1 Complex analysis method (CAM) tool

The effect of different fracture networks on drained areas, velocity profiles, and pressure depletion is quantified and visualized using complex analysis methods. Introductions to analytical element method applications to subsurface flow are found in several textbooks (Muskat 1949; Strack 1989; Sato 2015). Hydraulic fractures connected to a well act as line sinks (Weijermars and van Harmelen 2016). For multiple interval sources with time-dependent strength mk(t), the instantaneous velocity field at time t can be calculated from:

Traditional applications of CAM in subsurface flow models make use of integral solutions to model streamlines for steady state flows (Muskat 1949; Strack 1989; Sato 2015). A fundamental expansion of the CAM modeling tool is the application of Eulerian particle tracking of time-dependent flows, which was first explored in Weijermars (2014) and then benchmarked against numerical reservoir simulations in Weijermars et al. (2016).

Most current studies use numerical reservoir simulation to create pressure depletion plots as a proxy for the drained regions in the reservoir after production. CAM can determine the drained rock volume (DRV) by constructing time-of-flight contours to the well based on Eulerian particle tracking taking into account the changing velocity field (Weijermars et al. 2017a, b). This approach provides accurate determinations of the DRV (Parsegov et al. 2018) with the added benefit of identifying flow stagnation zones. Such stagnation zones or “dead zones” are defined as regions of zero flow velocity (Weijermars et al. 2017a, b), which create undrained areas that can be targeted for refracturing (Weijermars and Alves 2018; Weijermars and van Harmelen 2018). Another added advantage of CAM models is their infinite resolution at the fracture scale due to the method being gridless and meshless, resulting also in faster computational times compared to numerical simulations.

Modeling flow in fractured porous media using analytical solutions generated with time-stepped CAM models also allows the determination of pressure changes in the reservoir. Pressure depletion plots are calculated by evaluating the real part of the complex potential to quantify the pressure change at any location z at a given time t by:

Here \( \phi \left( {z,t} \right) \) is the potential function with pressure scaling based on fluid viscosity µ and permeability k of the reservoir. The actual pressure field at any given time can be computed from the following expression with P0 accounting for the initial pressure of the reservoir:

The basic premise of the CAM solution is placing the produced fluid volume back into the reservoir to determine the areas drained and the pressure response corresponding to this fluid placement. From replacing production into the reservoir based on history matching using decline curve analysis, the corresponding pressure depletion is obtained by simply reversing the signs of the values on the pressure scale from positive to negative (Weijermars et al. 2017b). For the pressure depletion plots later in this study, the spatial pressure change \( \Delta P\left( {z,t} \right) \) is shown.

4.2 Flux allocation and production modeling

This study assumes a synthetic production well of 8000 ft horizontal length and 80 transverse fractures with 100-ft spacing between them. This gives a total distance covered by the fractures of 7900 ft, leaving an untreated distance of 100 ft between the heel of the well and the first hydraulic fracture of the treatment plan. The flow simulation starts with a single fracture, using a base case model with a single-planar fracture, expanded with branched iteration models of the fracture geometry. The fracture trees initiating from single perforations are then expanded to multiple fractal systems for fracture stages with variations in complexity to observe the impacts on the DRV, velocity field, and pressure field. By assuming symmetry about the wellbore, we initially look at only one half of the fracture (half-length xf) to determine the effects on the flow velocities and pressure depletion for different fracture geometry models.

Current fracture propagation models that use simple planar fractures have the ability to predict proppant placement density which due to uneven placement can create zones of higher fracture conductivity (Parsegov et al. 2018). Though work has been done on proppant placement in complex fracture networks (Shrivastava and Sharma 2018) as we assume infinite fracture conductivity in our fractal network, uneven proppant placement is not considered in this model.

Production data from a typical Wolfcamp well used in a companion study (Parsegov et al. 2018) were used to produce a history matched type curve based on decline curve analysis. To match the production decline, the Duong decline method was used and found to give a total cumulative production over 30 years that is in line with forecasted EUR for wells in the Wolfberry play, Midland Basin under which the Wolfcamp Formation falls. Forecasts give an ultimate per well recovery estimated at 100,000–140,000 barrels of oil equivalent (Hamlin and Baumgardner 2012). The well used Duong decline parameters resulting in a cumulative production forecast of 102,069 bbls after a productive well life of 30 years.

Flux allocation was proportional to the relative surface areas of each branched fracture. For each successive iteration, the next generation of branches of the fracture network becomes progressively shorter, thereby automatically being allocated less of the overall production. This allocation method based on fracture length allows for the main fracture branches having the highest allocated flux, while the progressive iterations of the branched network will have less flux allocated. The flux allocation algorithm used is as follows:

where Z is a conversion factor of 5.61 to convert from barrels to ft3; S is the prorated factor to scale the total well production, for example scaling for one half-length of one fracture, \( S = (1/80) \times 0.5 = 0.00625 \).

Once the flux algorithm has been properly calculated, the next step is the creation of the time-dependent strength value to use in the velocity and pressure potential equations. This strength is scaled by reservoir properties such as the formation volume factor (B), porosity (n) residual oil saturation (Ro) (Khanal and Weijermars 2019) and fracture height (H) and is given as follows (data used is given in Table 2):

4.3 Drained rock volume (DRV)

For the determination of drainage areas, the CAM process utilizes the concept of flow reversal. The produced fluid is essentially placed back into the reservoir at the same rate as produced to determine where the fluid has been drained from. As such, the way in which the hydraulic fractures are represented will have a direct impact on the area which is drained, and the corresponding pressure gradient that drives the fluid flow back into the reservoir. The underlying assumption is that the larger the surface area of the hydraulic fracture the easier the flow into the matrix (and reverse), the narrower will be the width of the region drained around the fracture and thus the lower the pressure needed to achieve a given production rate. A fracture with smaller overall surface area (idealized planar hydraulic fracture, Fig. 5a) will need to have wider drainage width, whereas for the same production, a greater fracture surface area in contact with the matrix will mean a narrower drainage width (Fig. 5b).

Initially, we expected that a larger fractal dimension with more surface area would increase the injectivity of the matrix and require lower pressures to evacuate the reservoir fluid. Our models, however, show that once a constant total fluid production is used the overall pressure change remains the same regardless of the fracture network complexity. The models confirm the expectation that more complex fractal networks cause smaller lateral drained areas away from the fractures with greater local pressure variations. The reason for the localized pressure depletion peaks is that denser fracture networks with the same injectivity per fracture length will locally remove more fluid molecules from the matrix, thus resulting in larger pressure depletion locally.

The hydraulic fractal network is created and applied using an effective method of investigation by first modeling a small section of the horizontal wellbore. Because we use the method of fractals, a small sample of the well system should in fact be representative of the much larger drainage behavior of the well. This modeling strategy will also be beneficial in terms of computational and modeling time. Once the flow and pressure response have been determined based on individual fractal networks with increasing complexity, the investigation is extended to multiple fractal networks to investigate the possible effects of flow interference in fractured wells with numerous stages. Using this method both symmetrical and asymmetrical networks are modeled to determine changes in drained areas and flow response. The impact of fractal network complexity on reduction in flow stagnation zones is investigated to help determine the ideal fracture geometry to increase overall recoveries.

4.4 Model validation

The analytical solution to flow based on the complex analysis method has been validated against numerical simulators in previous work done. Weijermars et al. (2017a) compared the results of the analytical method for flow in planar fractures modeled as line sinks against a commercial simulator (ECLIPSE) that was augmented with a validated streamline tracing algorithm. This allowed for the comparison of time of flight contours as well as streamline patterns. This validation against the numerical simulator was achieved via a three-step process. Flow simulation in the commercial simulator provided pressure and flow rates on the six faces for each finite cell. These results were then imported into a streamline algorithm to obtain streamline tracing data, which was then imported in Petrel to visualize the actual streamlines. For the simple planar fracture case, the results from the numerical simulator matched well with the analytical complex analysis method proving validation of the complex analysis solution (Fig. 6). Our current model can be thought of as an extension of this validated case where we replace the simple planar fracture by our complex fractal network that comprises numerous line sinks acting within our reservoir. For a more detailed look at the validation, the reader is referred to the work by Weijermars et al. (2017a).

Streamlines with drainage contours. a Analytical solutions. Streamlines (blue), time of flight contours (red), stagnation points (green). b Commercial simulator. Streamlines and time of flight contours (rainbow colors). c Analytical pressure field. Fractures represented as black lines.

5 Results

5.1 Fractal network creation

The Lindenmayer (L-system) rewriting system based on fractals is used to construct numerous branching fractal networks. This system defines a complex object by replacing parts of the initial object according to given rewriting rules. The L-system, combined with information on fractal network geometry, fractal distance (d), deviation angle (α), and iteration number (i), allows the defining of rules for creating the overall network. A systematic workflow to investigate the effect of fractal network complexity is laid out in the subsequent sections.

The network structure is defined by a simple string or axiom using variables ‘F’ and ‘G’. Using these variables, branching is represented by the use of square brackets with the ‘+’ and ‘−’ symbols denoting either clockwise or anticlockwise branching angles. The iteration number gives the replacement rules, changing the branching complexity and is referred to as different fractal generations. A simple fractal code written in MATLAB from the M2-TUM group from the TU Munich was modified for our purpose of fractal network generation in 2D (available at http://m2matlabdb.ma.tum.de/author_list.jsp).

Axiom used for generation of the symmetrical fractal networks:

-

Symmetrical axiom rule = ‘F [+ G] [− G] F F [+ G] [− G]’.

Generated fractal networks using the above axiom and geometry parameters from Table 1 are shown below (Fig. 7).

5.2 Drainage by single symmetrical fractal networks

The first scenario investigated uses symmetrical fractal networks. The L-system with given fractal geometry parameters (Table 1) were incorporated in the CAM model to determine flow and drained rock volume responses for a variety of fractal geometries, ranging from a single-planar fracture to a third-generation symmetrical fractal network (Fig. 8). Moving from the planar fracture geometry towards higher fractal generations, an exponential increase occurs in the fracture surface area. Even a simple branching hydraulic fracture is shown to have a much larger surface area than the planar fracture. Assuming the well production rate is fixed, total drained volume of fluid per fractal network stage stays constant. Higher fractal generations cover a larger areal extent but drain narrower matrix depth, whereas the planar fracture drains broader distances away from the fracture (Figs. 5, 8).

a Fracture geometry modeled with planar fracture, first-generation symmetrical fractal network, second-generation, third-generation from left to right. b Velocity contour plot (ft/month) after 1 month production. c Pressure contour plots (drawdown in psi) after 1 month production. d Drained areas after 30 years production (drained area highlighted in red with tracked streamlines in yellow). Length scale in ft

The velocity contour plots show that when the fracture geometry evolves from planar to successive branched iterations there is a greater variability of the local velocities (Fig. 8b). As the branching complexity increases, individual fracture segments are spatially clustered close together, leading to small scale interferences resulting in higher flow velocities at the fracture network outer extremities, which is balanced by slower velocities between the branching fractures. The overall pressure change is found to be similar even as fracture complexity increases (Table 3). Pressure change is directly linked to the amount of production from the reservoir which is kept constant for all simulations. What is observed from the pressure depletion plots is that the greatest local pressure response occurs in areas with the highest fracture density (Fig. 8c). Comparing the response from the velocity and pressure plots, the greatest pressure change does not correlate with where fluid flows fastest around the fractures. However, there is a clear correlation between the steepest pressure gradients (regions where the pressure contours are spaced tightest) and the regions of highest flow velocity.

Drained areas are outlined by the time-of-flight contours inferred from particle tracking, based on the production allocation due to the selected fracture strengths (Fig. 8d). Results for a planar fracture geometry show equal drainage around the entire fracture. As more complex fractal networks are simulated, the results show the total drained area stays constant (regardless of fracture complexity as a constant production is used). However, the DRV regions are not distributed equally around the fracture segments in the network, leading to some small undrained areas between the branches of the fractal network.

5.3 Drainage by single asymmetrical fractal networks

Previous modeling (Sect. 5.2) assumed the generation of symmetrical fracture branches on both sides of the main branch. Due to the anisotropic nature of rocks, there is a strong possibility that these branches in reality may form asymmetrically due to changing rock properties. Using the L-system, different generations of branched asymmetrical fractures are modeled with the CAM to determine the impacts of asymmetry on flow and drained rock volumes (Fig. 9). The axiom rule for this asymmetrical fractal network is given as:

a Fracture geometry modeled with planar fracture, asymmetrical first-generation asymmetrical fractal network, second generation, third generation from left to right. b Velocity contour plot (ft/month) after 1 month production. c Pressure contour plots (drawdown in psi) after 1 month production. d Drained areas after 30 years production (drained area highlighted in red with tracked streamlines in yellow). Length scale in ft

Axiom used for generation of the asymmetrical fractal network:

-

Asymmetrical axiom rule = ‘F [− G] F F [+ G] [− G]’.

Asymmetric fractal networks still effectuate an increase in fracture surface area for successive iterations when compared to a planar fracture but less than for a symmetrical fracture network (Fig. 10). The velocity plots again show greater variability in flow velocities as the fractal network complexity increases with the greatest variation coinciding with the region where fracture density is highest (Fig. 9b). The asymmetrical fractal network shows similarity to the symmetrical fractal network in terms of overall pressure depletion and maximum/minimum flow velocities. The major difference with the asymmetric fractal network is the skewing of the highest pressure depletion contours to the area of highest fracture density (Fig. 9c). The premise that the steepest pressure gradients (areas where the pressure contours are tightest) correlate with areas of highest flow velocity is reinforced from these plots. Drained areas are found to conform to the areas of highest flow velocity (Fig. 9d) with small-scale stagnation areas found in between the highly branched areas as seen before in the symmetrical fracture network models (Fig. 8).

5.4 Interference effects of multiple fractal networks

Simulations in the previous section investigated the effect of moving from a single-planar fracture to more complex symmetrical and asymmetrical branching fractal networks. Modeling of a single fracture is the most logical point to start from but is not truly representative of modern hydraulically fractured wells with multiple perforations per stage and multiple stages, resulting in several hundred fracture initiation points at the perforations. The typical hydraulically fractured well completion in 2017 and beyond can have 50 stages or more. The spacing of the fractures may have a crucial impact on flow interference and thus affects drained areas and estimated ultimate recovery. This section seeks to determine the impact of interference effects on flow velocity, pressure depletion, and drained areas by simulating multiple fracture networks with different fractal network configurations. Using a base case of three planar fractures, comparisons of flow velocity, drained areas, and pressure depletion are made for various combinations of second-generation fractal networks (Fig. 11).

The base case models the flow response of three planar fractures and shows that with the given fracture half-length and fracture spacing, extremely low flow velocities occur between the central and outer fractures (Fig. 11a, left column). Flow stagnation zones are identified by velocity lows. These stagnation zones create areas in the reservoir that are left undrained due to the interference effect of the multiple fractures. The only way to drain these areas would be refracturing into the stagnation zones. The pressure depletion plot (Fig. 11b, left column) shows the largest pressure drop occurs between the fractures; however, this coincides with our lowest flow velocities and stagnation zones. This reinforces the idea put forward in Weijermars et al. 2017b that the pressure plots are poor proxies to recognize the reservoir areas drained by the fractures. The drained region after 30 years is visualized by the time-of-flight contours to the fractures (Fig. 11c, left column) and shows the majority of the drained area is at the outer fractures where we also have the highest flow velocities. Flow interference between the fractures creates the stagnation zones that lead to undrained rock volumes.

The second scenario investigates the response to three symmetrical second-generation fractal networks (Fig. 11, center column). Slower velocities are again found between the branched fractal areas but for this case are confined to a smaller area. This in turn means that branched networks create smaller stagnation zones, than with the planar fractures and thus the fractal network should be conducive to drain more of the reservoir space effectively (Fig. 11c, center column). Better drainage coverage from the fractal network means less refractures are needed between the initial fractures. For branching fractal networks, too small a fracture spacing will result in draining the same reservoir areas due to overlapping fractal networks creating an inefficient drainage process.

A third scenario looks at a central symmetrical fractal network flanked by two asymmetrical fractal networks (Fig. 11, right column). Again, the areas of highest velocity occur at the periphery of the fractures with the slowest flow between the fractal networks. From the various simulations, there is a clear correlation between higher fractal network complexity and suppression in the areal extent of flow stagnation zones. Reduction in stagnation zones in turn means more efficient drainage of our rock and smaller undrained areas between fracture stages.

One interesting simulation case uses a symmetrical fractal network followed by two asymmetrical networks that grow away from the first symmetrical network (Fig. 12). This orientation is used to represent the effect of stress shadowing during sequential hydraulic fracturing from toe to heel. Stress shadowing is the concept that fractures in the subsurface will tend to propagate away from the direction of already fractured rock due to changes in the stress regime (Nagel et al. 2013). The introduction of a poroelastic model to capture stress shadowing is outside of the scope of this work but to recreate this effect we have the first hydraulic fracture network at the toe being symmetrical due to no stress shadowing. The subsequent hydraulic fracture networks towards the heel of the well (Fig. 12) will be influenced by stress shadowing and this is captured by no branching of the fractal network in the direction of the previous hydraulic fracture at the toe leading to an asymmetrical fractal network. Using this fracture geometry to mimic stress shadowing, the area of greatest pressure depletion becomes skewed toward the initial fracture at the toe of the well (Fig. 12b). Comparison of the velocity and pressure plots in Fig. 12 shows the region with the largest pressure drop corresponds to the lowest flow velocities between the first toe fracture and the middle fracture. One would expect when the pressure drop is greater in a localized area, fluid velocity would be higher in that area of the reservoir. The physical explanation for the disparity between the regions with the largest flow rates and faster drainage being shifted with respect to the regions of highest pressure depletion as seen in our CAM model is as follows. Fluid moves fastest where the pressure gradients are steepest. The regions where fluid molecules are actively removed from the reservoir maintain the steepest pressure gradient. Adjacent regions with flow stagnation still will experience wider spacing between their fluid molecules leading to pressure depletion. This concept of the fundamental difference between pressure depletion and actual drained rock volume was first recognized in recent studies (Weijermars et al. 2017b; Weijermars and Alves 2018; Weijermars and van Harmelen 2018), using the same model tools outlined in the present study. Most current models use pressure plots to show drained areas but conclusions from this study show that velocity plots (rarely visualized in other models) give a better indication of actual drained rock volume. The fracture configuration of Fig. 12 results in a less effectively drained area near the initial toe fracture, whereas areas drained by the fractal networks at the heel side with less pressure depletion and higher flow velocities drain a slightly larger area, with a decrease in the size of the stagnation zone.

a Velocity contour plot for three branched fracture networks (ft/month) after 1 month production. b Pressure contour plots (drawdown in psi) after 1 month production. c Drained areas after 30 years production. Length scale in ft; surface area covered by symmetric/asymmetric three fracture networks is 4.9207 × 105 ft2

Another configuration investigated was a single-fracture stage with five fractures, each made up by a second-generation symmetrical fractal network (Fig. 13). This simulation mimics today’s industry standard of five fracture clusters per stage. Typical fracture distance in horizontal wells can go as low as 20 ft between perforation clusters. For this model, we maintain a fracture cluster spacing of 100 ft as used in previous simulations for ease of comparison and visual resolution. Similar to our base case with three symmetrical second-generation fractal networks (Fig. 11, central column), we again find slower velocities between the branched fractal networks, creating narrower flow stagnation areas. The stagnation regions are smaller than those created by planar fractures. A crucial take away from this simulation is that fracture interference effects, similar to those seen in other models, will occur equally for narrower spaced fractal networks. However, the much smaller fracture spacing used in the most recent well stimulation programs will only increase the intensity of local flow interference. Although more fractures increase the contact area with the matrix, the drained rock volume will not increase linearly with surface area increase due to the effect of increasing flow interference.

a Velocity contour plot for five symmetrical branched fracture networks (ft/month) after 1 month production. b Pressure contour plots (drawdown in psi) after 1 month production. c Drained areas after 30 years production. Length scale in ft; surface area covered by five fracture networks is 1.0201 × 106 ft2

5.5 Multiple full-length fractal networks

The preceding results all looked at half of the total fracture network length. The reason for this approach was the assumption of symmetry of the network on both sides of a horizontal wellbore. A final simulation looks at a full fracture length (2xf) for a single-fracture treatment stage with three perforation clusters, each generating fractal fractures (Fig. 14). Results show that the premise of flow symmetry about the wellbore is confirmed, as the velocity plots show contour patterns closely resembling those in Fig. 9b (center column). Flow stagnation points in Fig. 14 are shifted across the reservoir space to a location between the three fractures close to the wellbore, different from those seen in Fig. 11. The overall effect of a more complex fracture network is to reduce the spatial spread of flow stagnation zones, leading to improved efficiency of the DRV near the individual fractures.

6 Discussion

The true nature of hydraulic fracture geometries created in the subsurface during fracture treatment programs is still not properly resolved. Most fracture propagation models result in fractures that generate as simple planar features due to ease of modeling and the lack of inclusion of mechanical heterogeneity in such models. Meanwhile, numerous experimental and field observations show that planar fractures are too simple an assumption and they are more likely to exist as branching fracture networks. What is beyond doubt is that differences in the fracture geometry will have a distinct impact on the outcome of production forecasting models and history matching the actual production rates, drained areas and estimated ultimate recovery. Previous analytical solutions have looked at flow into parallel planar fracture arrays (Zhou et al. 2012; Yu et al. 2017) but failed to consider the effect on flow when fracture geometries are non-planar. Our method takes into account variable fracture geometries and visualizes the flow interference of fractal fracture networks. High-resolution visualizations of velocity and DRV areas are presented, which may substantially contribute to improve our current understanding of the flow process in hydraulically fractured reservoirs. The use of pressure depletion plots as proxies for drained rock volume is unreliable as has been highlighted in prior studies (Weijermars and van Harmelen 2018; Khanal and Weijermars 2019). In low permeability reservoirs, there occurs a distinct mismatch between the depth of pressure investigation and drained rock volume growth (Weijermars and Alves 2018), which is why the determination of the tracking of the time-of-flight of drained fluid to the hydraulic fractures of a well is required to delineate the DRV more accurately.

6.1 Interference effects

The effect of fracture geometry on flow interference was investigated using a fractal fracture network description in combination with the complex analysis methods (CAM) to model drainage patterns and the resulting DRV near hydraulic fractures. Several series of simulations were conducted to determine the impact on drained areas and flow velocities when the fracture geometry varies, starting from a single-planar fracture and evolving up to third-generation branching fractals. For greater fractal network complexity, the local area drained away from each individual fracture segment becomes smaller as compared to the area of drained regions near a single-planar fracture. The difference occurs because fractals have a larger fracture surface area and we are putting back a constant amount of produced fluid (via the principle of flow reversal) in both the single and fractal models. Consequently, the fractal network shows more variations in flow velocities and pressure depletion peaks as compared to a planar fracture. These extreme changes in velocity lead to uneven drainage by the fracture network with the possibility of small undrained areas due to stagnation points occurring between the branches.

A planar fracture geometry based on our model’s fracture spacing and half-length creates stagnation surfaces leading to relatively large undrained areas between the fractures. In contrast, the fractal network geometry shows a reduction in the effect and areal extent of the stagnation zones (as seen from a comparison of the velocity and drained area plots, Fig. 11), due to a decrease in the interference effect on flow. The position of flow separation surfaces separating the drainage regions of individual fractures is controlled by the ratio of the fracture length and fracture spacing (Weijermars et al. 2018). When the fracture spacing is greater than a quarter of the fracture length, the flow stagnation points occur midway between the individual fractures. For complex fractal networks, each fracture branch has a smaller length compared to a single-planar fracture. The smaller fracture branch lengths mean less flow interference will occur for an otherwise constant fracture cluster spacing.

6.2 Pressure depletion

Results show (Fig. 8c) that when the fracture surface area increases due to the more complex fractal networks, the average reservoir pressure change remains the same. One might expect that a greater fracture surface area to place fluid back into the reservoir model would result in smaller overall pressure changes. However, pressure peaks and lows show a larger spread where the fracture network complexity increases. The local variation in the pressure response is affected mostly by the fracture density. From the pressure plots (Fig. 11b), one can observe that areas with the highest fracture density give pressure contour depletion peaks. The current model uses a pre-fracture matrix permeability of 1 µD giving pressure changes in the magnitude of 106 psi (Fig. 14). When the permeability is changed to an after-fracture permeability of 1 mD, the pressure change magnitude drops to the range of 103 psi, which is in line with field observations. We assume this after-fracture permeability change is due to the creation of a network of microfractures in the rock that is termed the enhanced after-fracture permeability region.

6.3 Model limitations

One aspect that the current model does not consider is the effect of various fractal iterations on fracture conductivity. Beyond the concept of fracture conductivity decreasing with time due to partial fracture closure following reservoir pressure decline (Daneshy 2005), as we create successive iterations, each new branch will be less conductive due to fracture width reduction and the lesser ability for proppant placement. In the current model, all fractures are given a constant flux, whereas in reality, the shorter distal fracture branches may have a smaller aperture and consequently less proppant placement, which may suppress fluid flux. The use of microproppant to help prop these smaller secondary and microfracture networks can retain fracture conductivity and is a field currently under research (Kim et al. 2018). The impact of fracture closure with time can be looked at in future work by the addition of a parameter to further decrease strength of flux into the fractal network. Water blockage to flow due to imbibed water during the fracturing job and subsequent soaking period is also not accounted for. Another crucial point is that the current model ensured there was no overlapping of fractal branches either within a stage or by multiple stages. This may not always be true in nature, and with very low current fracture spacing, there is a possibility of these fractal networks crossing. The possible crossing of the fractal networks from sequential fracture clusters can result in communication between stages that is regularly seen in the field (Barree and Miskimins 2015; Li et al. 2016).

6.4 Practical implications

The impact of fractal fracture geometries on the DRV and stagnation zones is investigated in this study. Our models indicate that when the complexity of hydraulic fracture networks increases, this will suppress the occurrence of dead zones. In order to increase the DRV and boost the associated well productivity (and thus improve ultimate recovery), our models suggest that fracture treatment programs must find ways to create more complex fracture networks. The generation of such complex fracture networks is currently not included in concurrent fracture treatment design models, which limit the fracture development to mutually parallel planes. Because observational evidence from field experiments suggests that hydraulic fractures in hydrocarbon wells range from planar to multi-branched fractals (Huang and Kim 1993; Raterman et al. 2017), fracture treatment propagation models need to be modified to more realistically account for the development of complex fracture geometries that predictably follows from local geomechanical heterogeneities at the grain scale of rocks. The complex fracture geometry and fracture crossing provide a valid alternative explanation for the fact that tracer readings may overlap across fracture stages, which some commercial fracture propagation models presently attribute to the occurrence of longitudinal fractures parallel to the wellbore (Barree and Miskimins 2015).

7 Conclusions

The aim of this project was to more accurately represent the detailed flow patterns and drained rock volume (DRV) in unconventional reservoirs for a range of complex fractal fracture geometries. Such fractal flow models may help reservoir engineers to improve the hydrocarbon recovery rates. The simulations in this work show that the fracture geometry and complexity have a significant impact on the detailed hydrocarbon migration route near the fractures. Major conclusions realized from our study are as follows:

-

1.

A complex fracture network enhances the drained rock volume via two mechanisms. The first is that with more complex networks, the overall fracture surface area increases resulting in larger access to fluid stored in the reservoir matrix rock. The second mechanism is the suppression of stagnant flow zones when the complexity of the hydraulic fracture network increases.

-

2.

Hydraulic fracture treatment programs should stimulate the creation of bifurcating fractures as approximated by our fractal model. By reducing stagnant flow regions, the DRV will more effectively drain the reservoir. This will lead to improved drainage between the fractures, which will increase the estimated ultimate recovery from hydrocarbon wells.

-

3.

Using CAM, we are able to visualize in high resolution the effects of various fractal network geometries on flow and pressure response in the reservoir. We highlighted the fact that pressure plots, commonly used as proxies for drainage patterns, are poor proxies for the actual DRV. The DRV can be more accurate predicted using streamline tracking and time-of-flight contouring, as shown in our study.

-

4.

For planar fractures, stagnation zones in a three-fracture cluster occur close to the outer fractures, typically when the fracture spacing is less than a quarter of the fracture length (Fig. 11, left panel).

-

5.

Once fracture complexity is introduced in the form of fractal networks, the effect of the branching fractures leads to suppression of the flow stagnation areas, allowing for more efficient drainage (Fig. 11, center panel). The velocity plots for the fractal networks show a larger spread in the local variation of velocity than for the planar fractures.

-

6.

The highest velocities are still found at the periphery of the fractal networks for all cases. However, for asymmetrical fractal networks, there is a tendency for the highest pressure and velocity response to skew toward the areas of highest fracture density (Fig. 11, right panel).

-

7.

It will be necessary to determine whether the creation of complex fracture networks in the subsurface is solely dependent on the reservoir matrix properties (presence of natural fractures or matrix heterogeneities) or if fractal networks can be created by applying specific techniques during the hydraulic fracturing process. This requires the application of better diagnostic tools including the refinement of microseismic techniques to properly define and monitor created fractal network geometry.

-

8.

Improved capacity to engineer and model the propagation direction and control the generation of fractal geometries for hydraulic fractures are urgently needed in order to further increase the productivity of hydrocarbon wells by fracture treatment.

References

Al-Obaidy RTI, Gringarten AC, Sovetkin V. Modeling of induced hydraulically fractured wells in shale reservoirs using “branched” fractals. In: SPE annual technical conference and exhibition, 27–29 October. Amsterdam; 2014. https://doi.org/10.2118/170822-MS.

Arshadi M, Zolfaghari A, Piri M, Al-Muntasheri G, Sayed M. The effect of deformation on two-phase flow through proppant-packed fractured shale samples: a micro-scale experimental investigation. Adv Water Resour. 2017;105:108–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advwatres.2017.04.022.

Barree RD, Miskimins JL. Calculation and implications of breakdown pressures in directional wellbore stimulation. In: SPE hydraulic fracturing technology conference, 3–5 February. The Woodlands; 2015. https://doi.org/10.2118/173356-MS.

Berta D, Hardy HH, Beier RA. Fractal distributions of reservoir properties and their use in reservoir simulation. In: International petroleum conference and exhibition of Mexico, 10–13 October. Veracruz; 1994. https://doi.org/10.2118/28734-MS.

Cai L, Ding D-Y, Wang C, Wu Y-S. Accurate and efficient simulation of fracture–matrix interaction in shale gas reservoirs. Transp Porous Media. 2015;107:305–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11242-014-0437-x.

Cossio M, Moridis GJ, Blasingame TA. A semi-analytic solution for flow in finite-conductivity vertical fractures using fractal theory. In: SPE annual technical conference and exhibition, 8–10 October. San Antonio; 2012. https://doi.org/10.2118/163057-STU.

Daneshy AA. Pressure variations inside the hydraulic fracture and its impact on fracture propagation, conductivity, and screen-out. In: SPE annual technical conference and exhibition, 9–12 October. Dallas; 2005. https://doi.org/10.2118/95355-MS.

Fisher MK, Wright CA, Davidson BM, Goodwin AK, Fielder EO, Buckler WS, et al. Integrating fracture mapping technologies to optimize stimulations in the Barnett shale. In: SPE annual technical conference and exhibition, 29 September–2 October. San Antonio; 2002. https://doi.org/10.2118/77441-MS.

Frame M, Manna S, Novak M. Fractals: complex geometry, patterns, and scaling in nature and society; 2012. http://www.worldscinet.com/fractals/mkt/aims_scope.shtml. World Scientific Publishing Company Journal.

Gale J, Laubach S, Olson J, Eichhubl P, Fall A. Natural fractures in shale: a review and new observations. AAPG Bull. 2014;98(11):2165–216. https://doi.org/10.1306/08121413151.

Grechka V, Li Z, Howell R, Vavrycuk V. Single-well moment tensor inversion of tensile microseismic events. In: 2017 SEG international exposition and annual meeting, 24–29 September. Houston; 2017. SEG-2017-16890707.

Hamlin HS, Baumgardner RW. Wolfberry play, Midland Basin, West Texas. New York: AAPG Southwest Section Meeting; 2012.

Han G. Highlights from hydraulic fracturing community: from physics to modelling. URTeC 2768686; 2017.

Han JS. Plant simulation based on fusion of L-system and IFS. In: Shi Y, van Albada GD, Dongarra J, Sloot PMA, editors. Computational science—ICCS 2007. ICCS 2007. Lecture notes in computer science, vol 4488. Berlin: Springer.

Huang J, Kim K. Fracture process zone development during hydraulic fracturing. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci Geomech Abstr. 1993;30(7):1295–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-9062(93)90111-P.

Jones JR, Volz R, Djasmari W. Fracture complexity impacts on pressure transient responses from horizontal wells completed with multiple hydraulic fracture stages. In: SPE unconventional resources conference Canada, 5–7 November. Calgary; 2013. https://doi.org/10.2118/167120-MS.

Katz A, Thompson AH. Fractal sandstone pores: implications for conductivity and pore formation. Phys Rev Lett. 1985;54:1325. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.54.1325.

Khanal A, Weijermars R. Pressure depletion and drained rock volume (DRV) near hydraulically fractured parent and child wells (Eagle Ford Formation). J Pet Sci Eng. 2019;172:607–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2018.09.070.

Kilaru S, Goud BK, Rao VK. Crustal structure of the western Indian shield: model based on regional gravity and magnetic data. Geosci Front. 2013;4(06):717–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gsf.2013.02.006.

Kim BY, Akkutlu IY, Martysevich V, Dusterhoft R. Laboratory measurement of microproppant placement quality using split core plug permeability under stress. In: SPE hydraulic fracturing technology conference and exhibition, 23–25 January. The Woodlands; 2018. https://doi.org/10.2118/189832-MS.

Li J, Pei Y, Jiang H, Zhao L, Li L, Zhou H, Zhang Z. Tracer flowback based fracture network characterization in hydraulic fracturing. In: Abu Dhabi international petroleum exhibition and conference, 7–10 November. Abu Dhabi; 2016. https://doi.org/10.2118/183444-MS.

Li L, Lee SH. Efficient field-scale simulation of black oil in a naturally fractured reservoir through discrete fracture networks and homogenized media. SPE Reserv Eval Eng. 2008;11(4):750–8. https://doi.org/10.2118/103901-PA.

Lindenmayer A. Mathematical methods for cellular interactions in development II. Simple and branching filaments with two-sided inputs. J Theor Biol. 1968;18(3):300–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5193(68)90080-5.

Mandelbrot BB. Fractals: form, chance and dimension. San Francisco: WH Freeman and Co.; 1979. p. 16–365 (p. 1).

Maxwell SC, Urbancic TI, Steinsberger N, Zinno R. Microseismic imaging of hydraulic fracture complexity in the Barnett shale. In: SPE annual technical conference and exhibition, 29 September–2 October. San Antonio; 2002. https://doi.org/10.2118/77440-MS.

McKenzie NR, Hughes NC, Myrow PM, Banerjee DM, Deb M, Planavsky NJ. New age constraints for the Proterozoic Aravalli-Delhi successions of India and their implications. Precambrian Res. 2013;238:120–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2013.10.006.

Meyer BR, Bazan LW. A discrete fracture network model for hydraulically induced fractures: theory, parametric and case studies. In: SPE hydraulic fracturing technology conference, 24–26 January. The Woodlands; 2011. https://doi.org/10.2118/140514-MS.

Moinfar A, Varavei A, Sepehrnoori K, Johns RT. Development of an efficient embedded discrete fracture model for 3D compositional reservoir simulation in fractured reservoirs. SPE J. 2014;19:289–303. https://doi.org/10.2118/154246-PA.

Mukhopadhyay S, Bhattacharya AK. Bidasar ophiolite suite in the trans-Aravalli region of Rajasthan: a new discovery of geotectonic significance. Indian J Geosci. 2009;63(4):345–50.

Muskat M. Physical principles of oil production. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1949.

Nagel N, Zhang F, Sanchez-Nagel M, Lee B, Agharazi A. Stress shadow evaluations for completion design in unconventional plays. In: SPE unconventional resources conference Canada, 5–7 November. Calgary; 2013. https://doi.org/10.2118/167128-MS.

Olson JE, Taleghani AD. Modeling simultaneous growth of multiple hydraulic fractures and their interaction with natural fractures. In: SPE hydraulic fracturing technology conference, 19–21 January. The Woodlands; 2009. https://doi.org/10.2118/119739-MS.

Pandey CS, Richards LE, Louat N, Dempsey BD, Schwoeble AJ. Fractal characterization of fractured surfaces. Acta Metall. 1987;35(7):1633–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-6160(87)90110-6.

Parsegov SG, Nandlal K, Schechter DS, Weijermars R. Physics-driven optimization of drained rock volume for multistage fracturing: field example from the Wolfcamp Formation, Midland Basin. In: Unconventional resources technology conference held in Houston. Texas, 23–25 July 2018. https://doi.org/10.15530/urtec-2018-2879159.

Pradhan VR, Meert JG, Pandit MK, Kamenov G, Mondal MEA. Paleomagnetic and geochronological studies of the mafic dyke swarms of Bundelkhand craton, central India: implications for the tectonic evolution and paleogeographic reconstructions. Precambrian Res. 2012;198–199:51–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2011.11.011.

Raterman KT, Farrell HE, Mora OS, Janssen AL, Gomez GA, Busetti S, Warren M. Sampling a stimulated rock volume: an Eagle Ford example. In: Unconventional resources technology conference. Austin, 24–26 July 2017. https://doi.org/10.15530/urtec-2017-2670034.

Sato K. Continuum analysis for practical engineering. London: Springer; 2015. p. 300.

Sang G, Elsworth D, Miao X, Mao X, Wang J. Numerical study of a stress dependent triple porosity model for shale gas reservoirs accommodating gas diffusion in kerogen. J Nat Gas Sci Eng. 2016;32:423–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2016.04.044.

Shrivastava K, Sharma MM. Proppant transport in complex fracture networks. In: SPE hydraulic fracturing technology conference and exhibition, 23–25 January. The Woodlands; 2018. https://doi.org/10.2118/189895-MS.

Strack ODL. Groundwater mechanics. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall; 1989.

van Harmelen A, Weijermars R. Complex analytical solutions for flow in hydraulically fractured hydrocarbon reservoirs with and without natural fractures. Appl Math Model. 2018;56:137–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apm.2017.11.027.

Wang W, Su Y, Sheng G, Cossio M, Shang Y. A mathematical model considering complex fractures and fractal flow for pressure transient analysis of fractured horizontal wells in unconventional reservoirs. J Nat Gas Sci Eng. 2015;23:139–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2014.12.011.

Wang W, Su Y, Zhou Z, Sheng G, Zhou R, Tang M, et al. Method of characterization of complex fracture network with combination of microseismic using fractal theory. In: SPE/IATMI Asia Pacific oil & gas conference and exhibition, 17–19 October. Jakarta; 2017. https://doi.org/10.2118/186209-MS.

Wang WD, Su YL, Zhang Q, Xiang G, Cui SM. Performance-based fractal fracture network model for complex fracture network simulation. Pet Sci. 2018;15:126–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12182-017-0202-1.

Warren JE, Root PJ. The behavior of naturally fractured reservoirs. Soc Pet Eng J. 1963;1963(3):245–55.

Warpinski NR, Moschovidis ZA, Parker CD, Abou-Sayed IS. Comparison study of hydraulic fracturing models—test case: GRI staged field Experiment No. 3 (includes associated paper 28158). SPE Prod Facil. 1994;9:7–16. https://doi.org/10.2118/25890-PA.

Weijermars R. Visualization of space competition and plume formation with complex potentials for multiple source flows: some examples and novel application to Chao lava flow (Chile). J Geophys Res. 2014;119(3):2397–414. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013JB010608.

Weijermars R, Alves IN. High-resolution visualization of flow velocities near frac-tips and flow interference of multi-fracked Eagle Ford wells, Brazos County, Texas. J Pet Sci Eng. 2018;165:946–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2018.02.033.

Weijermars R, van Harmelen A. Breakdown of doublet recirculation and direct line drives by far-field flow in reservoirs: implications for geothermal and hydrocarbon well placement. Geophys J Int. 2016;206:19–47. https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggw135.

Weijermars R, van Harmelen A. Shale reservoir drainage visualized for a Wolfcamp Well (Midland Basin, West Texas, USA). Energies. 2018;11:1665. https://doi.org/10.3390/en11071665.

Weijermars R, van Harmelen A, Zuo L. Controlling flood displacement fronts using a parallel analytical streamline simulator. J Pet Sci Eng. 2016;139:23–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2015.12.002.

Weijermars R, van Harmelen A, Zuo L, Alves IN, Yu W. High-resolution visualization of flow interference between frac clusters (part 1): model verification and basic cases. In: SPE/AAPG/SEG unconventional resources technology conference, 24–26 July. Austin; 2017a. SPE URTeC 2670073A.

Weijermars R, van Harmelen A, Zuo L. Flow interference between frac clusters (part 2): field example from the Midland Basin (Wolfcamp Formation, Spraberry Trend Field) with implications for hydraulic fracture design. In: SPE/AAPG/SEG unconventional resources technology conference, 24–26 July. Austin; 2017b. SPE URTeC 2670073B.

Weijermars R, van Harmelen A, Zuo L, Alves IN, Yu W. Flow interference between hydraulic fractures. SPE Reserv Eval Eng. 2018;21(4):942–60. https://doi.org/10.2118/194196-PA.

Weng X, Kresse O, Cohen CE, Wu R, Gu H. Modeling of hydraulic fracture network propagation in a naturally fractured formation. SPE Prod Oper. 2011;26(4):368–80. https://doi.org/10.2118/140253-PA.

Xu W, Thiercelin MJ, Ganguly U, Weng X, Gu H, Onda H, et al. Wiremesh: a novel shale fracturing simulator. In: International oil and gas conference and exhibition in China, 8–10 June. Beijing; 2010. https://doi.org/10.2118/132218-MS.

Yu W, Wu K, Zuo L, Tan X, Weijermars R. Physical models for inter-well interference in shale reservoirs: relative impacts of fracture hits and matrix Permeability. In: SPE/AAPG/SEG unconventional resources technology conference, 1–3 August. San Antonio; 2016. https://doi.org/10.15530/URTEC-2016-2457663.

Yu W, Xu Y, Weijermars R, Wu K, Sepehrnoori K. Impact of well interference on shale oil production performance: a numerical model for analyzing pressure response of fracture hits with complex geometries. In: SPE hydraulic fracturing technology conference and exhibition, 24–26 January. The Woodlands; 2017. https://doi.org/10.2118/184825-MS.

Yu W, Sepehrnoori K. Embedded discrete fracture model (EDFM) for complex fracture geometry. Shale gas and tight oil reservoir simulation (pp. 155–200). Cambridge: Gulf Professional Publishing, an imprint of Elsevier; 2018.

Zhang X, Thiercelin MJ, Jeffrey RG. Effects of frictional geological discontinuities on hydraulic fracture propagation. In: SPE hydraulic fracturing technology conference, 29–31 January. College Station; 2007. https://doi.org/10.2118/106111-MS.

Zhou W, Banerjee R, Poe BD, Spath J, Thambynayagam M. Semi-analytical production simulation of complex hydraulic fracture network. In: SPE international production and operations conference & exhibition, 14–16 May. Doha; 2012. https://doi.org/10.2118/157367-MS.

Zolfaghari A, Ghanbari E, Dehghanpour H, Bearinger D. Fracture characterization using flowback salt-concentration transient. SPE J. 2016;21(1):233–44. https://doi.org/10.2118/168598-PA.