Abstract

Evidence suggests that in the professional education of teachers the moral goals are currently a neglected topic in favor of the subject matter and knowledge. The constructivist instructional approach VaKE (Values and Knowledge Education) addresses this problem by combining the moral and epistemic goals through the discussion of moral dilemmas. The main research question of this practice-based study was whether teacher educators can improve their instructional practice by using VaKE. We describe an empirical study of a teacher educator who used VaKE in order to (i) facilitate pre-service teachers to solve moral conflicts which they are faced with in their workplace learning and to (ii) increase the moral climate in his course. 58 pre-service teachers who formed two classes participated in the study. The study consisted of three research phases: In the first research phase the types of the pre-service teachers’ moral conflicts were examined. In the second research phase the most frequent types of moral conflicts were used as a basis for an explorative quasi-experimental pre-posttest study. This study investigated the effects of VaKE compared to a traditional case-analysis approach with regard to the pre-service teachers’ application of discourse-oriented actions for conflict resolution. In the third phase, a case study method was used comprising a random sample of seven pre-service teachers chosen from each class to investigate the perceived learning climate during the intervention. The results indicate that VaKE provides the possibility to combine the moral and epistemic goals of the professional education of teachers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the education for the teaching professions two types of general goals can be distinguished which have been called “moral and epistemic purposes” by Sockett (2008) or double assignment in teacher education by Tapola and Fritzen (2010). While the epistemic goals, for example the acquisition of research based scholarly knowledge, are considered as the core of teacher professionalism (Darling-Hammond and Bransford 2005), the moral goals, as for instance the development of pre-service teachers’ moral judgment competence and their preparation to foster the moral development of their students, are not always taken for granted (e.g., Willemse et al. 2008). The moral goals can be justified by referring to teaching being a moral practice which is heavily value-laden (Bullough 2011).

However, although teacher educators and teachers state that they would like to achieve the moral goals, they rarely implement them into their practice (e.g., Ryan and Bohlin 1999). The main obstacle lies in the crowded curriculum which emphasizes epistemic goals and as a consequence does not give enough room for the moral aspects of education. As a corollary teachers do not know how to address the moral goals in school (Klaassen 2002). Particularly in situations of moral conflicts (conflicts between different values or norms; Shapira-Lishchinsky 2011) teachers miss adequate strategies to come up with a responsible and appropriate solution.

Values and Knowledge Education (VaKE) is a constructivist instructional concept developed at the University of Salzburg that provides a possible solution to this problem. Constructivist-based learning methods have proved to be effective in fostering moral judgment competence (e.g., Schlaefli et al. 1985) and the acquisition of applicable knowledge (e.g., Collins et al. 1989). In a nutshell, in a VaKE process the learners are confronted with a dilemma addressing moral issues which they discuss; if the dilemma is conceived appropriately, it will trigger knowledge questions, which are then answered by the learners through an information search in relevant sources available. In a VaKE process, then, the learners perform a double research process: ethical justification (research with respect to argumentation in favor or against moral values in the given dilemma situation), and empirical (research with respect to looking at empirical evidence necessary for their argumentation). We have shown that through VaKE the learners acquire at least as much knowledge, and sometimes more, than in content-focused teaching (Patry et al. 2013). The applicability of VaKE has already been shown in teacher education (Weinberger 2014; Keast and Marangio 2015); the present paper adds new insights with respect to the effectivity of VaKE to foster moral action and addresses the issue of practice-based research of teaching with VaKE on different levels:

-

a.

The teacher educator who is supported in doing a study practices VaKE as a teaching tool in his classes and evaluates whether VaKE is effective in his teacher education.

-

b.

The teaching relates to the students’ practical experiences by addressing specific moral conflicts they encounter in their practicum. The research issue is, here, to what degree it is possible to capitalize on the students’ practice in teaching.

-

c.

The aim of this teaching process is to contribute to an improvement of their future practice in two regards: first, in dealing adequately with moral conflicts in their future classes, and second, in applying VaKE in their own teaching. The former is assessed in the practicum following the teaching (immediate transfer to new situation). The sustainability of this teacher education, however, cannot be researched in the present study.

This corresponds to Borko et al. (2008) distinction according to which, teacher educators engage in practitioner research on two levels: First, they want to improve their own professional practice as a teacher educator. Second, they want to facilitate pre-service teachers’ experiences as researchers of their own practice. In the present study both levels are addressed. (a) Since VaKE provides much freedom for both teacher and learner it is important that the teacher educator using VaKE evaluates his or her teaching to be able to adapt it to the particularities of his or her learners and the context. (b) From a constructivist point of view, meaningful learning is best achieved when issues of direct concern to the learners are addressed in teaching, namely their own practice (e.g., Lave and Wenger 1991); this practice-based learning can easily be combined with practitioner research in the sense of integrating teaching through research and research through teaching with VaKE (Patry 2014). Through their own research, the pre-service teachers get an even deeper understanding of VaKE than by only applying it (see c above).

The main research question of this study is whether teacher educators can improve their instructional practice with regard to the double assignment by using VaKE addressing authentic problems of the students. It is of particular interest (i) which moral conflicts pre-service teachers are faced with during their workplace learning, (ii) whether these self-experienced moral conflicts can be used in VaKE to facilitate pre-service teachers’ conflict resolution competence, and (iii) whether VaKE can contribute to a moral climate. Practice-based research can be a valuable way of inquiry to answer the main research question. With practice-based research there is emphasis on local contexts which are recognized as inevitable mediators of change and shapers of practice (Cochran-Smith and Lytle 2009, p. 57). We assume that the instructional tool VaKE has the potential to change and shape practice if it is adapted to local contexts, such as to the particularities of the learners.

Background and Theoretical Framework

Moral Conflicts in Teaching

Like almost all other areas of professions and occupations, teaching is an inherently moral practice (e.g., Campbell 2010; Goodlad et al. 1990; Hansen 2001). However, according to Strike (1990), there are some moral issues that are particular for teaching: First, teachers work for the most part in isolation and what goes on in the classroom is largely unknown to other colleagues or the parents. Second, this isolation is accompanied by the lack of a collectively agreed upon ethical codex for the practice of teaching. Finally, teachers deal with children who are particularly vulnerable to harmful treatment in two distinct ways: 1) they are relatively powerless and 2) due to their immaturity they lack the capacity to resist immoral treatment. In a similar vein, Fenstermacher (1990, p. 133) states that “(t)he teacher’s conduct, at all times and in all ways, is a moral matter. For that reason alone, teaching is a profoundly moral activity”. According to Bullough (2011) the kind and quality of the relationship between the teacher and the student influences what is learned and how it is learned by the student. In addition, teachers experience contradictions and moral conflicts in their everyday practice because the very nature of “teaching” requires choices involving moral judgments (Hostetler 1997; Joseph and Efron 1993; Maslovaty 2000). Moral conflicts in teaching are defined as problematic situations with no clear-cut answer for the involved teacher, usually arising from a conflict between different values or norms including moral values, which demand reflective judgments about responsible solutions (Shapira-Lishchinsky 2011). Sometimes moral conflicts appear as moral dilemmas requiring a decision between mutually exclusive options (Ehrich et al. 2011).

A few studies provide an insight into teachers’ moral conflicts and dilemmas. Tirri (1999) identified four main categories of moral conflicts in teaching, namely 1) matters related to teachers’ or colleagues’ work such as punishing a pupil who disturbs the class, grading of an academically weak pupil, or treating situations in which a colleague was found to act unprofessionally; 2) pupils’ moral behavior regarding school and work – as for instance pupils’ negative attitude towards learning, and tormenting behavior by some pupils; 3) rights of minority groups such as dealing with different religious values; and 4) common rules at school, for instance differing views of colleagues regarding school rules. In a subsequent study Tirri and Husu (2002) showed that all moral conflicts deal with human relationships and their different views of perceiving ‘the best interest of the child’. Based on these and other empirical findings Shapira-Lishchinsky (2011) presents a systematic theoretical framework of five different types of teachers’ moral conflicts. The first type of moral conflicts is between the caring climate and the formal climate. The caring climate refers to the attention of individual and social needs, while the formal climate stresses compliance with different organizational rules (e.g., school rules, educational standards). Typical moral conflicts of this type include discipline problems (Tirri 1999). Distributive justice versus school standards is the second type of moral conflicts. Distributive justice relates to the fairness of outcomes, such as when teachers use the principle of equity (outcomes allocated based on inputs such as the student’s effort) or the principle of equality (outcomes allocated based on equal input) to assess the fairness or unfairness of the outcome (e.g., rewards, grades). School standards describe criteria which schools apply for reaching decisions. This type of moral conflicts occurs when teachers perceive these criteria as unfair when viewed against the outcome. The third type of moral conflicts is between confidentiality and school rules. This type of moral conflicts arises when teachers have to decide between sustaining the trust of a confiding pupil and adhering to the school rules which require reporting the entrusted information to the administration, the parents, the school psychologist or other institutions. Loyalty to colleagues versus school norms, the fourth type of moral conflicts, arises when teachers witness the negligent or harmful behavior of a colleague, or are informed of such behavior which is not in accordance with school or educational norms, and find it difficult to confront the colleague (Campbell 2008). The fifth type of moral conflicts appears when the educational agenda of the pupil’s family is not consistent with the school’s educational standards. This type of moral conflict occurs when the teacher’s perception of the child’s best interest differs from that of the parents. Although existing research sheds light on the types of in-service teachers’ moral conflicts there is little published data on pre-service teachers’ moral problems (Millwater et al. 2004). Studies of pre-service teachers’ classroom management strategies in their practicum reveal that discipline problems are one of their greatest challenges because they struggle with competing discourses concerning institutional needs for order and the individual needs of children (McNally et al. 2005; Stoughton 2007). It is expected that pre-service teachers’ moral conflicts focus particularly on issues of discipline.

In light of the preceding discussion the question arises how teachers deal with the different moral conflicts. Evidence suggests that teachers lack competencies to solve moral conflicts in a professional way (Campbell 2008; Shapira-Lishchinsky 2011). Although teachers see the moral goals as important part of their professional practice they miss adequate strategies to come up with a responsible and adequate solution. For example, Klaassen (2002) describes teachers who react quite emotionally in case of a moral conflict with pupils and tend to adopt an authoritarian approach to the situation. They do not initiate a moral discussion in a systematic manner. And Campbell (2008) reports about pre-service teachers’ experience in their practicum, witnessing unprofessional and sometimes harmful conduct of their supervising teachers. These findings do not imply that teachers act immorally most of the time but that they miss adequate strategies to solve morally laden situations in a professional way. Such strategies are presented in the theory of professional discourse morality (Oser and Althof 1993). According to this framework of teacher ethos five distinct basic forms of decision making in situations of interpersonal conflicts can be distinguished. The first conflict solution strategy is avoiding. It is characterized by the teacher’s avoidance to manage the conflict and to take responsibility. Delegating, the second conflict solution strategy, is characterized by an attempt to shift the responsibility to another hierarchical level of decision-making, such as to the principal, the school administration, a professional counsellor, the parents or colleagues. Unilateral (“single-handed”) decision-making is the third conflict solution strategy. Teachers with this predominant orientation solve problems on their own and avoid negotiating distinct interests. The fourth conflict solution strategy is named incomplete discourse. Teachers who employ this strategy try to listen to all people who are involved in the conflict. However, the final decision to solve the conflict is made by the teacher. Complete discourse, the fifth conflict solution strategy, is characterized by an attempt to involve the pupils in all parts of the process of decision-making. Teachers employing this strategy “presuppose” that students are able to take responsibility and to find a good solution. According to this theory of teacher ethos discursive conflict solution strategies (incomplete and complete discourse) are the bases of a comprehensive professional morality because they involve the articulation of personal values, beliefs, interests, and needs and the integration of all concerned parties into the process of finding solutions. A discursive procedure can be learned and includes (i) creating a “roundtable” situation in which all persons are able to freely express their view, (ii) giving occasion for validating claims, (iii) presupposing that every participant is rational and honest, and (iv) having faith that this procedure will result in the morally best solution (Oser and Althof 1993). Empirical studies of teachers’ discourse-orientations indicate that they rarely use discursive strategies. Instead, they mostly adopt single-handed decision strategies to solve moral conflicts in their classroom (Oser and Althof 1993; Tirri 1999).

According to the reported empirical findings teachers seem to be insufficiently equipped to make professional moral judgments. Studies from many countries document that there is a lack of explicit attention to moral goals within programs of professional education of teachers (Campbell 2008; Revell and Arthur 2007; Ryan and Bohlin 1999; Willemse et al. 2008). According to these studies the main obstacle for implementing moral goals in teacher education arises from the fact that this issue is neglected in the curriculum and practice in favor of the subject matter. Drawing on this unsatisfactory situation Sockett and LePage (2002, p. 171) conclude that “[m]oral language is missing in the classrooms; but it is also missing in the seminar rooms and lecture halls of teacher education.” A possible solution to this problem is addressed by the instructional approach VaKE (Values and Knowledge Education; Patry et al. 2007, 2013).

VaKE (Values and Knowledge Education)

VaKE is based on the constructivist teaching and learning paradigm for the development of moral judgment competence (Kohlberg 1984; this will be described below) through the discussion of moral dilemmas (e.g., Schlaefli et al. 1985), as well as for the acquisition of factual knowledge (e.g., Piaget 1985; Tobias and Duffy 2009) through inquiry-based learning (e.g., Bell et al. 2010). The starting point of the learning process is a moral dilemma which raises questions about what should be done; the dilemma discussion then triggers questions about what is important to know. While the first questions address moral judgment, the second ones refer to factual knowledge of a specific subject or across subjects. The integration of moral judgment and knowledge acquisition provides the possibility to address the moral goals without neglecting the epistemic goals in different subjects. VaKE can be used in different settings including vocational learning and education. In this study we describe the application of VaKE as a moral decision making framework in the context of the professional education of teachers.

The underlying theory of moral judgment competence is Rest et al. (1999) further development of Kohlberg’s lifespan developmental theory which they applied to adulthood and the professions. When faced with a moral dilemma a person resolves the values conflict according to one of the following developmental perspectives each representing a progressively more mature way of moral reasoning: First, the personal interest schema describes individuals who lack a sociocentric perspective. The justification for a conflict solution as morally right is based on the personal stake of the actor, stressing notions such as survival or personal advantages. Second, the maintaining norms schema indicates an increased sociocentric perspective. The justification for a conflict solution as morally right refers then to the maintenance of rules which are clear, consistent and apply to everyone. Third, the postconventional schema or the principled level of moral reasoning is based on a sociocentric perspective. Moral dilemmas are resolved on the basis of procedures aiming at producing consensus through appealing to moral principles and logical coherence. Empirical studies testing hypotheses deduced from this theoretical framework of cognition for teacher development show that teachers at more principled levels of moral reasoning (i) hold a more humanistic-democratic view of student discipline, (ii) consider different viewpoints, (iii) show more tolerance for student disturbances, and (iv) stress student understanding of the purpose of the rules (Chang 1994). A strong congruence exists between judgments and actions (Johnson and Reiman 2007). Teachers at more principled levels of moral reasoning let students more often participate in rule making and promote understanding for the reason for the rules (Johnston and Lubomudrov 1987), show more listening behavior (Reiman and Peace 2002), are more able to empathize with students and more tolerant of diverse viewpoints (O’Keefe and Johnston 1989). The most effective interventions for stimulating moral growth with dilemma discussions involve real-life dilemmas (Snarey and Samuelson 2008).

As shown repeatedly (e.g., in teacher education see Cummings et al. 2007) the discussion of moral dilemmas in the tradition of Kohlberg is one of the most effective ways to nurture this kind of ability of moral judgment. Such dilemma discussions are used in VaKE; however, in these dilemmas the scope is expanded in that content related issues are addressed as well, thus fostering the acquisition of factual knowledge.

Knowledge plays a crucial role during the dilemma discussion. New facts can spread the effects of this discussion in three directions: to strengthen the favored argumentation of the defended standpoint, to follow the opposing arguments and hence to change the standpoint, or to develop a new perspective on a better problem solution. The aspect of knowledge acquisition follows the constructivist developmental and learning theory of Piaget (1985). According to this view, first, meaningful learning is not a passive process of absorbing new information but an active one of building knowledge structures; this applies also to teacher learning (Feiman-Nemser 2008). A dilemma discussion that leaves open questions about factual information is such an opportunity as shown within the theoretical framework of inquiry-based learning (e.g., Bell et al. 2010; Kuhn et al. 2000) because the students will attempt to answer these questions. Second, learning is defined as an active process of altering mental structures in function of the interactions with the social context. These interactions can result in so-called perturbations if new concepts turn out to be contradictory to existing concepts. Such perturbations occur predominantly in cases of dissent with one or several others’ points of view. Two possibilities allow the integration of a new concept: either by assimilation or by accommodation. Assimilation means that the new concept can be integrated into the existing structure in the sense of “more of the same”. Accommodation means a change or partial reorganization of the mental structures as a precondition to integrate the new concept. With regard to moral judgement accommodation nurtures the ability to find arguments in favor or against certain values on a more principled level. Third, active learning facilitates transfer of learning which is defined as “the ability to extend what has been learned in one context to new contexts” (Bransford and Cocking 2000, p. 51) because the learners strive for understanding based on their personal experience (Macaulay 2000). Different authentic problems – in this study moral conflicts emanating from the students’ personal experience – are particularly powerful to trigger learning through situated cognitions and thus to foster the transfer to future practical application situations (Brown et al. 1989; Lave and Wenger 1991).

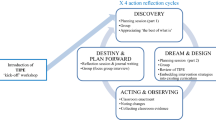

In its main tenets the prototypical course of a VaKE-lesson is constructed with respect to these theoretical aspects. It comprises 11 steps which are summarized in Fig. 1 (Patry et al. 2013).

Steps in a prototypical VaKE-lesson (adapted from Patry et al. 2013, p. 567)

The learning process starts with the introduction of a content related moral dilemma story, raising the question what the protagonist should do. The key facts of the story and the competing values at stake are analyzed (step 1). The learners write down their argument and announce their decision. They recognize the different justifications for a decision (step 2). This decision is followed by the discussion of the arguments within small groups of learners. The discussion is guided by questions like (i) which consequences are likely to follow the protagonist’s action?; (ii) would it be okay if every person solved the conflict in this way?; (iii) how would you like to be treated as a person who is concerned in such a situation?; (iv) what do you think the person feels in this particular situation?; (v) are any moral rules or laws relevant? (step 3). Subsequently, the groups’ experiences concerning the results of the argumentation are exchanged although the dilemma discussion is usually not finished yet. More importantly, at this stage of learning, open questions regarding necessary knowledge are collected (step 4). The learners organize themselves in groups which search for the necessary information in a systematic way using different sources of knowledge, while the teacher acts as a manager and counsellor of the whole endeavor. The teacher may also provide relevant information and take the role of an expert (step 5). The learners exchange their new information so that all persons have the same level of knowledge (step 6). Based on this, the discussion in the group will be continued (step 7) using the new knowledge to strengthen or weaken the previous arguments. In a general discussion the groups present the results of the dilemma discussion (current state of negotiation) and all learners discuss their favored arguments (step 8). If the knowledge base is not yet sufficient, the steps 4 to 8 are repeated once again. The learners can use additional sources of knowledge and maybe set another focus (e.g., to satisfy curricular needs) (step 9). In the final synthesis the learners present the solved problem or the current state of the solution of the whole group. This can be done in didactically sophisticated ways such as through a role-play (step 10). In the generalization the learners deal with similar issues to broaden the perspective. They apply their solutions to similar moral conflicts from their field of experience (step 11).

The effectivity of VaKE depends on several conditions (Weyringer et al. 2012). First, in a constructivist learning setting the teacher gives priority to the learning goals of the students, challenges their experiences, thinking and judgment, and gives guidance only if it is necessary. She or he takes the role of a facilitator rather than a master or moralizer. Second, the effectivity of a dilemma discussion depends on the establishment of a learning climate which is characterized by mutual respect and trust (Lind 2005). Each participant has one vote and one voice regardless of her or his status and power. It is important that the learners are able to discuss their own arguments and feel absolutely safe to express their own opinion even if, for instance, this opinion is contradictory to the teacher’s opinion. Third, the teacher has to change her or his role according to the activities within the different steps of VaKE. During the dilemma discussion, for example, she or he facilitates the moral reasoning of the learners through challenging questions whereas during the information search he or she can take the role of an expert.

Several empirical studies in school settings support the effects of VaKE on knowledge construction (e.g., Weinberger 2006), as well as on the ability to moral argumentation (Nussbaumer 2009), and on the development of identity and personality (Weyringer 2008). We have made positive experiences with VaKE in several settings of vocational learning and education in the social and healthcare professions (Weyringer et al. 2013). A number of studies emphasize the applicability and effectivity of VaKE in the professional education of teachers. For example, Keast and Marangio (2015) showed that through VaKE pre-service teachers realized the value-ladenness of science. In a study by Weinberger et al. (2013) VaKE was effective to foster the quality of moral arguments. Weinberger et al. (2011) showed that knowledge functions as an important means for changing moral decisions in VaKE. And Pnevmatikos and Patry (2012) investigated perspective-taking in VaKE-related activities. The present study adds the existing literature by addressing the question of promoting moral action through VaKE by using authentic moral conflicts.

Hypotheses

According to theoretical underpinnings (Shapira-Lishchinsky 2011) and the results of empirical studies mentioned above (e.g., Tirri 1999) teachers’ moral conflicts are based on interpersonal relationships. Conflicts are always about values, and interpersonal conflicts are about different (groups of) people defending different, incompatible values. Since teaching and education is always social (interpersonal), and as far as teaching and education are concerned, teachers’ and pre-service teachers’ moral conflicts are about interpersonal relationships. This holds for the choice of the content to be taught since it is for the students that the teachers choose their topics and how to teach them. This is even more so the case for explicitly interpersonal conflicts between teachers and students like discipline problems which are one of the greatest challenges for pre-service teachers (Stoughton 2007). Based on this reflection, the first hypothesis is that most interpersonal conflicts reported by pre-service teachers are different types of discipline problems.

Such conflicts can be addressed in VaKE in the professional education of teachers (see above) as an approach to address authentic moral conflicts through moral dilemma discussion in combination with the inquiry-based acquisition of knowledge that might be helpful in such situations like problem solving strategies. Such discussions emphasize discursive conflict resolution strategies which are considered to be justifiable ways to address the moral issues of interpersonal conflicts (Oser and Althof 1993). Through active learning and the use of different authentic moral problems transfer of learning can be enhanced (e.g., Bransford and Cocking 2000; Brown et al. 1989). The second hypothesis claims that learning with VaKE increases the application of pre-service teachers’ discourse-oriented actions to resolve interpersonal conflicts in their practicum. Moral dilemma discussions include activities which are conducive to a moral climate like mutual trust, opportunities to discuss, and respect for each other’s view. The third hypothesis is that this applies also to VaKE, namely that VaKE fosters a moral learning climate.

Methods

Context and Participants

This practice-based study was conducted in a private College of Teacher Education in Austria. Colleges of Teacher Education in Austria educate teachers for primary schools and general secondary schools. Both school types cover the compulsory school education of pupils between the ages of 6 and 14 years. The academic program of prospective teachers for compulsory schools is complemented with weekly workplace learning in associated primary or secondary schools. This practicum comprises the preparation and performance of one school-lesson by the pre-service teacher.

Fifty-eight pre-service teachers (13 males; mean age: 22.7; range: 19.6 to 40.1 years) participated in the study. The participants formed two classes (N1 = 32; N2 = 26); they were in the second year of their professional education for becoming a teacher in general secondary schools. Both classes were taught by the same teacher educator who was also the primary researcher of this study. All participants gave informed consent to take part in the study. They were assured that the data would be treated confidentially. The study was embedded in a 1 ECTS credit course called “Conflict management in the context of social learning” which both classes attended consecutively. This course lasted 8 units (each lasting 90 min) and was scheduled once every second week in the summer semester of 2013. The course contents focused on types and emergence of conflicts in school, conflict solution strategies, and classroom management methods.

Research Design and Procedure

The study consisted of three research phases, each of which addressed one hypothesis. In the first phase, which addressed the first hypothesis, the teacher educator examined the types of moral conflicts the pre-service teachers are faced with during their practical school training. In the second phase addressing the second hypothesis, the teacher educator chose four most frequently occurring types of moral conflicts and used them as basis for an explorative quasi-experimental pre- and posttest study to investigate the effects of VaKE with regard to the pre-service teachers’ application of discourse-oriented actions for conflict resolution. The two classes were assigned randomly to the VaKE or a traditional case-analysis condition. The standardized case-analysis approach was based on the principles of Merseth (1996) which include (i) studying the case individually, reviewing important data and answering study questions provided with the case by the teacher educator, (ii) studying the case in small groups, sharing insights and opinions, and (iii) discussing the case in the larger seminar group under the guidance of the teacher educator. In the comparison group the focus was on content-centered learning; moral discussions were not included. The participants of the comparison group received VaKE-lessons after the completion of the study. The interventions in both groups lasted 4 units of 90 min and in each of these units the teacher educator used one of the four chosen practical moral conflicts. In both groups the same moral conflicts were used and the same contents were addressed, namely strategies of classroom management and behavioral modification, legal issues of pupils’ treatment and the discourse approach. In the third phase, which was related to the third hypothesis, the teacher educator used a case study method comprising of a random sample of seven pre-service teachers chosen from each class to investigate the perceived learning climate during the intervention. This research phase started after the completion of the intervention.

Instruments

The data were collected using two instruments. First, it was part of the homework assignment to write reflections upon ten school-lessons of the practicum with a particular focus on interpersonal conflict situations (it was not possible to ask for more reflections due to the ECTS workload allotted to this course). The instruction was as follows: “Write down an interpersonal conflict situation in which you had difficulty to decide the right way to act”. Two specifications were given: 1. Describe the conflict situation as detailed as possible, and 2. describe the solution strategy used as detailed as possible. In the first phase five reflections of each pre-service teacher were content-analyzed with regard to the type of moral conflict (hypothesis 1). Since the reflections were not declared as research investigations but were homework assignments used in teaching, the assessment can be considered as non-reactive (Webb et al. 1981). Permission was obtained from each student to use the data. In the second phase the ten reflections of each pre-service teacher (five for pretest and five for posttest) were content-analyzed with regard to discourse-oriented actions (hypothesis 2).

The second instrument was a semi-structured interview (Bogdan and Biklen 1992, pp. 104ff). The main question for the interview was as follows: “How did you perceive the learning climate during the intervention?” All interviews were digitally audio-recorded, transcribed in smooth verbatim style and crosschecked for accuracy. The interviews were used in the third research phase to examine the perceived learning climate during the intervention with VaKE (hypothesis 3).

Analyses

The text material of the reflections and the transcribed interviews were analyzed following the procedure for qualitative content analysis outlined by Mayring (2014, p. 10) who defines qualitative content analysis as a mixed methods approach which includes the “assignment of categories to text as qualitative step, [and] working through many text passages and analysis of frequencies of categories as quantitative step.” The structuring technique within the qualitative step was used, which is characterized by the assignment of the text units to deductively conceived categories based on prior theoretical concepts. After a first pilot coding, the categories were revised, partially reformulated, and some new categories were added. In order to ensure the quality of the content analysis, intercoder-reliability was checked (Krippendorff 2013, pp. 267ff). A second person who was instructed and trained to apply the category system coded independently 50 % randomly chosen written reflections and all the transcribed interviews. Coding disagreements were discussed and resolved through consensus about the proper coding.

In the first research phase, the category system for analyzing the type of interpersonal conflict was derived from empirical studies about the types of moral conflicts and dilemmas of teachers (e.g., Stoughton 2007; Tirri 1999). The coding unit was determined as the whole paragraph of the description of the conflict situation. Five reflections for each person were analyzed. The intercoder-reliability prior to achieving consensus in cases of disagreement proved to be very high (Krippendorff’s Alpha: .87). Differences in the frequencies of the types of interpersonal conflicts were analyzed using a chi-squared test. In the second research phase, the category system for analyzing types of discourse-oriented teacher actions were based on the theoretical framework and practical background of VaKE (Patry et al. 2013) and the discursive morality (Oser and Althof 1993). Inductively conceived categories emanating from the text were added. The recording unit was determined as the description of the solution strategy; the coding unit was specified as phrases and sentences which refer to a specific discourse-oriented action. Each category was coded once if it appeared several times in one reflection. For each measuring time five reflections for each person were analyzed. The intercoder-reliability for the content analysis prior to consensus proved to be very high (Krippendorff’s Alpha: .94). Differences between pre- and posttests were analyzed using an analysis of variance with repeated measurement. In the third research phase, the category system for analyzing the perceived learning climate was derived from the theoretical and practical background of VaKE. The coding unit was defined as phrases and sentences referring to a specific factor of the learning climate. 14 interviews (seven for each group) were analyzed. The intercoder-reliability prior to consensus was satisfying (Krippendorff’s Alpha: .79). Differences between the experimental and comparison groups were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance.

Results

Types of Moral Conflicts

Table 1 summarizes the absolute and relative frequencies of types of moral conflicts the pre-service teachers are faced with in their practicum. The first and most frequently mentioned category in both classes is “Disturbance” which deals with situations such as talking during class, tapping with feet or causing paper to rustle. The second category is “Provocation”. Provocations are defined as actions of pupils that cause the pre-service teacher to become angry. Pre-service teachers describe situations such as calling them with a nickname, calling them “student”, or mocking them. The third category is “Refusal to learn” which is defined as saying or showing that a pupil is not willing to do something the pre-service teacher wants the pupil to do. Pre-service teachers mention situations as ignoring assignments, not participating in teamwork activities, or throwing down pencils and notebooks. The fourth category is “Aggressive behavior” which refers to some pupil’s tormenting behavior against another pupil. Aggressive behavior is defined as behavior that causes physical or emotional harm to others. Classroom situations of this category include scuffles, teasing, or bullying. “Conventional rule transgression” appeared to be a further category. Conventional rules are determined as rules which are contingent, local, and facilitate social coordination through shared understandings of etiquette (Huebner et al. 2010). They also include school rules. Typical classroom situations of conventional rule transgressions imply leaving the classroom without permission, or remaining seated when the pre-service teacher enters the class. The category “Moral rule transgression” includes for example lying or cheating. And the category “Loyalty conflict” which was mentioned least frequently points to competing values between the pre-service teacher and the class teacher. Most of the reported interpersonal conflicts deal with matters of discipline and student behavior. The result of a chi-squared test indicates significant differences between the frequencies of types of moral conflicts (χ 2(6) = 107.10; p < .001; ϕ = .62). The frequencies between the two classes do not differ significantly (χ 2(6) = 3.38; ns; ϕ = .21). These findings support hypothesis 1.

Application of Different Discourse-Oriented Actions

Table 2 indicates the mean scores of the discourse-oriented actions for the experimental and comparison groups. The first row lists the types of interpersonal actions which were mentioned by the pre-service teachers. The category “Listen to the pupil” refers to paying attention to the pupil in order to hear what she or he says. The category “Asking questions for clarification” refers to the teacher’s questions in order to make the conflict easier to understand (e.g., “Could you explain what happened?”). The category “Getting close to the pupil” is defined as approaching the pupil to initiate a private conversation. Asking questions about reasons for a specific behavior refers to the category “Asking questions for justification” (e.g., “Why are you crying?” “Why aren’t you writing?”). The category “Proposing a resolution” includes suggestions for conflict resolutions to be considered by the pupil (e.g., “What do you think about this suggestion?”). Assertions of feelings belong to the category “I-statements” (e.g., “I am angry about the noise!”). The category “Sitting next to the pupil” specifies the intention of the teacher to get at eye-level with the pupil. Questions to view the situation from an alternate point-of-view relate to the category “Asking questions for perspective-taking” (e.g., “What do you think he feels about this?”). And the category “Asking questions for resolution” refers to the teacher’s questions to think about a possible solution to the conflict (e.g., “What do you suggest to resolve this problem?”).

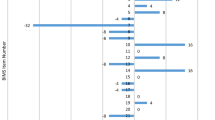

A descriptive analysis of Table 2 shows that discourse-oriented actions such as listen to the pupil or asking questions for clarification are more frequently mentioned by the pre-service teachers than asking questions for perspective taking or asking questions for resolution. In the comparison group pre-service teachers do not express I-statements or ask for resolution in case of a moral conflict. Given the naturalistic context of the study, it was not possible to control for all potential differences between the participants in the experimental and comparison groups. However, an analysis of variance showed that the pretest scores of each discourse-oriented action did not differ between the participants of both groups (p ranges from .079 for “Getting close to the pupil” to .839 for “Asking questions for justification”).

In order to determine differences between the experimental and comparison groups a repeated measures analysis of variance was performed. The dependent variable was a composite discourse-oriented action score built from the nine items in order to enhance reliability. Time (pretest vs. posttest) was the within subject factor and group (experimental group vs. comparison group) the between subject factor. The interaction of time by group was found to be significant (F(1,56) = 16.67, p < .001, partial η 2 = .23). Further analysis of this effect using paired samples t-tests with Bonferroni corrected alpha-level reveal a significant increase of the discourse-oriented action score of the experimental group (t(31) = 6.71, p < .001, d = 1.02) from M = .23 (SD = .28) in the pretest to M = .72 (SD = .52) in the posttest, whereas in the comparison group no significant difference was found (t(25) = .40, ns, d = .09; M pretest = .27, SD = .25; M posttest = .31, SD = .44). The main effect time was significant (F(1,56) = 22.08, p < .001, partial η 2 = .23), indicating a significant difference of the discourse-oriented action score summarized across both groups. Furthermore, the main effect group was significant (F(1,56) = 4.32, p < .05, partial η 2 = .07), indicating a significant difference of the discourse-oriented action score summarized across both measurement times. These findings support hypothesis 2.

Perceived Moral Learning Climate

The results of the content analysis of the transcribed interviews with regard to the perceived moral learning climate are presented in Table 3. The pre-service teachers mentioned five categories. The category “Openness” is defined as the free expression of one’s true view about the moral conflict. As an example, a pre-service teacher stated: “Everyone was allowed to express her or his opinion. It was a real discussion which was characterized by all students having the possibility to express contradictory arguments.” The category “Trust” relates to the belief that the learning group and the teacher educator are reliable. One pre-service teacher, for example, said: “In a way trust has increased. We had the feeling that our views are welcome and appreciated.” The category “Respect” is defined as acting in a way which shows that the acting person is aware of the human rights of the other person. A pre-service teacher stated: “I also had the impression that we students expressed contradictory opinions to each other in a more respectable way than usually.” The category “Freedom from anxiety” relates to explicit statements about safety and a missing feeling of fear. One pre-service teacher remarked: “I had no fear to express my argument because it was clear for us that each argument was appreciated and that an argument can’t be wrong. None of the students was laughing about an uncommon argument.” The category “Authenticity” is defined as actions which are true to one’s personality. One person stated: “It is usually not very common in our classes that we are allowed to express our real opinions. But during the VaKE-classes it was possible.”

In order to determine whether there is a difference between the experimental and comparison group a one-way analysis of variance with the total score of each participant was performed. Levene’s test indicated unequal variances (F = 11.39, p < .05), so a Welch’s F-test was performed (Moder 2010). The results indicate a significant difference between the experimental and comparison group (F(1,7) = 10.26, p < .05, partial η 2 = .46). Participants in the experimental group mention significantly more often a category than the participants in the comparison group. The descriptive analysis indicates differences between the experimental and comparison groups primarily with regard to “Trust” and “Respect”. Most of the interviewed pre-service teachers who learned according to VaKE perceived mutual trust and respect, which are important conditions for moral dilemma discussions, whereas participants who learned according to the content-centered case-analysis approach did not mention these factors. The categories “Openness”, “Freedom from anxiety” and “Authenticity” can be found in both groups. A possible explanation is the discussion-based setting in both groups. In a summary, the results support hypothesis 3.

Discussion

Previous studies of VaKE in teacher education focused on the applicability of this approach addressing questions related to pre-service teachers’ moral values and moral judgment. The present practice-based study went further and investigated the effectivity of VaKE with a particular focus on promoting moral action. It was of particular interest whether VaKE can help pre-service teachers to deal more appropriately with moral conflicts they are faced with in their practicum, namely through discourse-oriented actions, and whether VaKE enhances the moral climate.

First, the study showed the importance of using practice-based research in the present context. Practice-based research is defined, in its most general form, as “investigation undertaken in order to gain new knowledge partly by means of practice and the outcomes of that practice” (Candy 2006, p. 1). More specifically, the systematic inquiry of teachers into their own practice, labelled as practitioner research or practitioner inquiry (Cochran-Smith and Lytle 2009; Groundwater-Smith and Mockler 2009; Mockler and Sachs 2011), has a long tradition dating back to Dewey’s conception of the teacher as a reflective practitioner (1904). Indeed, addressing moral problems in class requires a high degree of reflexivity, and through capitalizing on the students’ practical experiences when addressing these problems and using a constructivist teaching approach (VaKE) it was hoped that this reflexivity can be enhanced towards dealing more competently with future moral problems - whether the teacher education was successful in this regard could not be investigated within this study.

Several major genres of practitioner research can be distinguished (Cochran-Smith and Lytle 2009). The present study belongs to the genre the scholarship of teaching (Hutchings et al. 2011; Perry and Smart 2007) which describes systematic research of higher education faculty across disciplines who investigate their own teaching practices (in the present study, the teacher educator using VaKE) and student learning “with an eye not only to improving their own classroom but to advancing practice beyond it” (Hutchings and Shulman 1999, p. 13); the latter issue refers to the students’ use of their practical experience and the presumable sustainability of their learning for future practice. The common characteristics of all versions of practitioner research in education according to Cochran-Smith and Lytle (2009) are all met in the study:

-

i.

the teacher educator assumes the dual role as practitioner (by practizing VaKE with a focus on students’ practical experiences) and researcher (by evaluating VaKE),

-

ii.

the researcher’s workplace is the site of inquiry,

-

iii.

the problems and issues within professional practice (on one hand, moral problems in class, on the other using VaKE as teaching tool) are the focus of investigation,

-

iv.

knowledge generation as a means to improve practice through application of that knowledge (by improving teacher education courses),

-

v.

the boundaries between practice and inquiry are blurred insofar as the same issues, namely moral problems, are the topic of the research as well as of the teaching, further, the assessments were both homework assignments for the teaching process as well as scientific investigation.

-

vi.

both teaching and research are intentional, which relates to the planned and deliberate nature of research, and

-

vii.

they are systematic, which refers to organized methods of data collection and analyses.

While the results of the study seem fairly conclusive, it must be underlined that several restrictions apply. First, VaKE was a new teaching and learning method for the pre-service teachers which could have resulted in a particular motivation to work harder. Second, only one instrument was used to assess the discourse-oriented actions and the moral climate. Second instruments for both variables would have contributed to enhancing the validity of the results. Third, the teacher educator as a researcher taught in both groups and knew the hypotheses. He could have unconsciously influenced the participants. Fourth, the sample of pre-service teachers was quite small (only two classes), so that one can question the representativeness of the results. Fifth, the non-random sample could have resulted in a biased sample, making it difficult to generalize the collected data. And finally, there is no indication for the sustainability of the effects. The findings can be explained by the short time distance between intervention and measurement. These restrictions were due to the conditions, particularly to time constraints of the learners. To strengthen the assertibility of the conclusions replication studies are necessary, which are planned.

Overall, the study showed that VaKE can be an effective tool to improve teacher education courses if the pre-service teachers apply it to their own practical situations. This application can be supported by the teacher educator’s research activities to adapt VaKE to the particularities of his or her learners (pre-service teachers). The practical application of VaKE for practical problems is part of a program which includes teaching about VaKE in different settings of vocational learning as well; this can capitalize on the results of this study. It could be shown that learning with VaKE fosters a positive learning climate based on mutual trust and respect. A positive climate provides an important foundation for effective teaching and supportive learning environments in school and in professional education (Taylor 1997). It could also be shown that VaKE fosters meaningful learning resulting in an immediate transfer of the acquired knowledge to real moral conflicts in the classroom. Transfer is considered as the ultimate goal of each professional and vocational education (Macaulay 2000).

Problematic teaching situations, such as classroom disturbances, refusal of learning, aggressive behavior, rule transgression, and provocations as experienced by the pre-service teachers, are important issues and need to be addressed in a professional education of teachers (Stoughton 2007); according to constructivist views it is particularly important that the pre-service teachers perceive the respective problematic situation as their own (Lave and Wenger 1991). So they do first a research on such situations in their (restricted) practical experience; this is the first step of practitioner research. The research on their own practice includes also their reactions, in this case the discourse-oriented actions. These results will be important in the VaKE process.

In the VaKE process itself dilemma situations are addressed. As recognized in a previous study (Weinberger et al. 2013) self-determined dilemma situations are more powerful in VaKE than dilemma situations that are imposed from the outside. Further, the pre-service teachers’ own reactions – discursive or not – are addressed in the VaKE process. The latter hence is a research process about the students’ own practice, which turns into a learning process. And as it turns out, indeed, the students recognize the appropriateness of discourse-oriented actions, which means that in the VaKE process they question their own behavior and eventually adapt it to better fulfil the requirements that they have formulated themselves during VaKE. This result, we assume, can also be accounted for by the moral climate as perceived by the students, with particular emphasis on mutual trust and respect which have been recognized by the majority of the interviewed participants.

The practice-based study has shown that using VaKE as a means to integrate the moral and epistemic goals in a professional education of teachers is possible and effective. It extends previous findings by showing that it is possible to use authentic moral conflicts drawn from personal experience, in the particular case dealing with social interaction issues, and it has made it plausible that this practice-based approach has an impact on the pre-service teachers’ behavior, namely the application of discourse-oriented actions in interpersonal conflicts. This experience corroborates experiences in other contexts (Patry et al. 2013) and provides further insights into the use of VaKE in teacher education (Keast and Marangio 2015; Pnevmatikos and Patry 2012; Weinberger et al. 2011; Weinberger 2014).

We do not claim, however, that VaKE should substitute all of the common approaches in teacher education. Instead we suggest that there are important topics that allow addressing the moral and epistemic goals simultaneously. We also do not claim that VaKE is the only approach that fulfills the double assignment in teacher education. There are certainly other methods, and maybe these are more effective. On the other hand we also do not contend that VaKE itself cannot be improved with respect to different educational settings – here again further research is necessary.

References

Bell, T., Uhrhahne, D., Schanze, S., & Ploetzner, R. (2010). Collaborative inquiry learning: models, tools and challenges. International Journal of Science Education, 32(3), 349–377.

Bogdan, R. C., & Biklen, S. K. (1992). Research for education. An introduction to theories and methods. Boston: Pearson.

Borko, H., Whitcomb, J. A., & Byrnes, K. (2008). Genres of research in teacher education. In M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman-Nemser, D. J. McIntyre, & K. E. Demers (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 1017–1049). New York: Routledge.

Bransford, B., & Cocking (2000).

Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), 32–42.

Bullough, R. V. (2011). Ethical and moral matters in teaching and teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27, 21–28.

Campbell, E. (2008). Preparing ethical professionals as a challenge for teacher education. In K. Tirri (Ed.), Educating moral sensibilities in urban schools (pp. 3–18). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Campbell, E. (2010). Ethical knowledge in teaching. A moral imperative of professionalism. Education Canada, 46(4), 32–35. Retrieved 15 April 2015 from http://www.cea-ace.ca.

Candy, L. (2006) Practice based research: A guide. CCS Report: 2006-V1.0 November. Retrieved 23 April 2015 from http://www.creativityandcognition.com/resources/PBR%20Guide-1.1-2006.pdf.

Chang, F. Y. (1994). School teachers’ moral reasoning. In J. R. Rest & D. Narvaez (Eds.), Moral development in the professions: Psychology and applied ethics (pp. 71–83). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. L. (2009). Inquiry as stance. Practitioner research for the next generation. New York: Teachers College Press.

Collins, A., Brown, J. S., & Newman, S. E. (1989). Cognitive apprenticeship: Teaching the crafts of reading, writing, and mathematics. In L. B. Resnick (Ed.), Knowing, learning, and instruction: Essays in honor of Robert Glaser (pp. 453–494). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cummings, R., Harlow, S., & Maddux, C. D. (2007). Moral reasoning of in-service and pre-service teachers: a review of the research. Journal of Moral Education, 36(1), 67–78.

Darling-Hammond, L., & Bransford, J. (2005). Preparing teachers for a changing world. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Dewey, J. (1904). The relation of theory to practice in education. In J. Dewey, S. C. Brooks, F. M. McMurry, & C. A. McMurry (Eds.), The relation of theory to practice in the education of teachers: Third yearbook of the national society for the study of education, part 1. Bloomington: Public School Publishing.

Ehrich, L. C., Kimber, M., Millwater, J., & Cranston, N. (2011). Ethical dilemmas: a model to understand teacher practice. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 17(2), 173–185.

Feiman-Nemser, S. (2008). Teacher learning: How do teachers learn to teach? In M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman-Nemser, D. J. McIntyre, & K. E. Demers (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education. Enduring questions in changing contexts (3rd ed., pp. 697–705). New York: Routledge.

Fenstermacher, G. D. (1990). Some moral considerations on teaching as a profession. In J. I. Goodlad, R. Soder, & K. A. Sirotnik (Eds.), The moral dimensions of teaching (pp. 130–151). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Goodlad, J. I., Soder, R., & Sirotnik, K. A. (Eds.). (1990). The moral dimension of teaching. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Groundwater-Smith, S., & Mockler, N. (2009). Teacher professional learning in an age of compliance: Mind the gap. Dordrecht: Springer.

Hansen, D. T. (2001). Teaching as a moral activity. In V. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (4th ed., pp. 826–857). Washington: American Educational Research Association.

Hostetler, K. D. (1997). Ethical judgment in teaching. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Huebner, B., Lee, J. J., & Hauser, M. D. (2010). The moral-conventional distinction in mature moral competence. Journal of Cognition and Culture, 10, 1–26.

Hutchings, P., & Shulman, L. E. (1999). The scholarship of teaching: new elaborations, new developments. Change, 31(5), 10–15.

Hutchings, P., Huber, M., & Ciccone, A. (2011). The scholarship of teaching and learning reconsidered. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Johnson, L. E., & Reiman, A. J. (2007). Beginning teacher disposition: examining the moral/ethical domain. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23, 676–687.

Johnston, M., & Lubomudrov, C. (1987). Teachers’ level of moral reasoning and their understanding of classroom rules and roles. Elementary School Journal, 88, 64–77.

Joseph, P. B., & Efron, S. (1993). Moral choices/moral conflicts: teachers’ self-perceptions. Journal of Moral Education, 22(3), 201–220.

Keast, S., & Marangio, K. (2015). Values and knowledge education (VaKE) in teacher education: benefits for pre-service teachers when using dilemma stories. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 167, 198–203.

Klaassen, C. A. (2002). Teacher pedagogical competence and sensibility. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18, 151–158.

Kohlberg, L. (1984). Essays on moral development, Vol. 2: The psychology of moral development. San Francisco: Harper & Row.

Krippendorff, K. (2013). Content analysis. An introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Kuhn, D., Black, J., Keselman, A., & Kaplan, D. (2000). The development of cognitive skills to support inquiry learning. Cognition and Instruction, 18(4), 495–523.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lind, G. (2005). Moral dilemma discussion revisited – The Konstanz Method. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 1(1). Retrieved 15 April 2015 from http://ejop.psychopen.eu/article/view/345/html.

Macaulay, C. (2000). Transfer of learning. In V. E. Cree & C. Macaulay (Eds.), Transfer of learning in professional and vocational education (pp. 1–26). New York: Routledge.

Maslovaty, N. (2000). Teachers’ choice of teaching strategies for dealing with socio-moral dilemmas in the elementary school. Journal of Moral Education, 29(4), 429–444.

Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Klagenfurt, Austria. Retrieved 18 March 2015 from http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173.

McNally, J., I’Anson, J., Whewell, C., & Wilson, G. (2005). They think that swearing is okay”: first lessons in behavior management. Journal of Education for Teaching, 31(3), 169–185.

Merseth, K. K. (1996). Cases and case methods in teacher education. In J. Sikula (Ed.), Handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 722–744). New York: Macmillan.

Millwater, J., Ehrich, L. C., & Cranston, N. (2004). Preservice teachers’ dilemmas: ethical or not? International Journal of Practical Experiences in Professional Education, 8(2), 48–58.

Mockler, N., & Sachs, J. (Eds.). (2011). Rethinking educational practice through reflexive inquiry. Essays in honour of Susan Groundwater-Smith. Dordrecht: Springer.

Moder, K. (2010). Alternatives to F-test in one way ANOVA in case of heterogeneity of variances (a simulation study). Psychological Test and Assessment Modeling, 52(4), 343–353.

Nussbaumer, M. (2009). Das Unterrichtskonzpt VaKE in Verbindung mit der Argumentationsstruktur von Max Miller [The teaching concept VaKE in connection with the argumentation structure of Max Miller] (Unpublished bachelor’s thesis). Universität Salzburg, Austria.

O’Keefe, P., & Johnston, M. (1989). Perspective-taking and teacher effectiveness: a connecting thread through these developmental literatures. The Journal of Teacher Education, 40(3), 14–20.

Oser, F., & Althof, W. (1993). Trust in advance: on the professional morality of teachers. Journal of Moral Education, 22(3), 253–276.

Patry, J.-L. (2014). Mokymas per tyrimus ir tyrimai per mokyma: Moksliniu ir subjektivviu teoriju palyginimas. Teaching through research – research through teaching: comparing scientific and subjective theories. Aukštojo Mokslo Kokybė/The Quality of Higher Education, 11, 12–43. doi:10.7220/2345-0258.11.1. in Lithuanian and English.

Patry, J.-L., Weyringer, S., & Weinberger, A. (2007). Combining values and knowledge education (VaKE). In D. N. Aspin & J. D. Chapman (Eds.), Values education and lifelong learning (pp. 160–179). Dordrecht: Springer Press International.

Patry, J.-L., Weinberger, A., Weyringer, S., & Nussbaumer, M. (2013). Combining values and knowledge education. In B. J. Irby, G. Brown, R. Lara-Alecio, & S. Jackson (Eds.), The handbook of educational theories (pp. 565–579). Charlotte: Information Age Publishing.

Perry, R. P., & Smart, J. C. (2007). The scholarship of teaching and learning in higher education: An evidence-based perspective. Dordrecht: Springer.

Piaget, J. (1985). The equilibration of cognitive structures. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Pnevmatikos, D. & Patry, J.-L. (2012). Perspective taking in VaKE-related activities. Paper presented in a Symposium at the 38th Annual Conference of the Association for Moral Education (AME). San Antonio, Texas.

Reiman, A., & Peace, S. D. (2002). Promoting teachers’ moral reasoning and collaborative inquiry performance: a developmental role-taking and guided inquiry study. Journal of Moral Education, 31(1), 51–66.

Rest, J., Narvaez, D., Bebeau, M., & Thoma, S. (1999). A Neo-Kohlbergian approach: the DIT and schema theory. Educational Psychology Review, 11(4), 291–324.

Revell, L., & Arthur, J. (2007). Character education in schools and the education of the teachers. Journal of Moral Education, 36(1), 79–92.

Ryan, K., & Bohlin, K. (1999). Building character in schools. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Schlaefli, A., Rest, J., & Thoma, S. (1985). Does moral education improve moral judgment? A meta-analysis of intervention studies using the defining issues test. Review of Educational Research, 55(3), 319–352.

Shapira-Lishchinsky, O. (2011). Teachers’ critical incidents: Ethical dilemmas in teaching practice. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27, 648–656.

Snarey, J., & Samuelson, P. (2008). Moral education in the cognitive developmental tradition: Lawrence Kohlberg’s revolutionary ideas. In L. P. Nucci & D. Narvaez (Eds.), Handbook of moral and character education (pp. 53–79). New York: Routledge.

Sockett, H. (2008). The moral and epistemic purposes of teacher education. In M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman-Nemser, & D. J. McIntyre (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education. Enduring questions in changing contexts (pp. 45–65). New York: Routledge.

Sockett, H., & LePage, P. (2002). The missing language of the classroom. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18, 159–171.

Stoughton, E. H. (2007). How will I get them to behave?” Pre-service teachers reflect on classroom management. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23, 1024–1037.

Strike, K. A. (1990). Teaching ethics to teachers: what the curriculum should be about. Teaching and Teacher Education, 6(1), 47–53.

Tapola, A., & Fritzen, L. (2010). On the integration of moral and democratic education and subject matter instruction. In C. Klaassen & N. Maslovaty (Eds.), Moral courage and the normative professionalism of teachers (pp. 149–174). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Taylor, I. (1997). Developing learning in professional education. London: Open University Press.

Tirri, K. (1999). Teachers’ perceptions of moral dilemmas at school. Journal of Moral Education, 28(1), 31–47.

Tirri, K., & Husu, J. (2002). Care and responsibility ‘in the best interest of the child’. Relational voices of ethical dilemmas in teaching. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 8(1), 65–80.

Tobias, S., & Duffy, T. M. (Eds.). (2009). Constructivist instruction. Success or Failure? New York: Routledge.

Webb, E. J., Campbell, D. T., Schwartz, R. D., Sechrest, L., & Grove, J. B. (1981). Nonreactive measures in the social sciences (2nd ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Weinberger, A. (2006). Kombination von Werterziehung und Wissenserwerb. Evaluation des konstruktivistischen Unterrichtsmodells VaKE (Values and Knowledge Education) in der Sekundarstufe I [Combination of values education and knowledge acquisition. Evaluation of the constructivist teaching model VaKE (Values and Knowledge Education) on the secondary level I]. Hamburg, Germany: Kovac.

Weinberger, A. (2014). Diskussion moralischer Fallgeschichten zur Verbindung moralischer und epistemischer Ziele [The combination of moral and epistemic purposes through moral cases-analysis]. Beiträge zur Lehrerbildung, 1, 60–72.

Weinberger, A., Gastager, A. & Patry, J.-L. (2011). VaKE in teacher education. How do preservice teachers argue? Paper presented at the AME (Association for Moral Education)-conference in Nanjing, China.

Weinberger, A., Patry, J.-L., Nussbaumer, M. & Weyringer, S. (2013). Teacher education for responsible teaching. Paper presented at the EARLI-conference “Responsible Teaching and Sustainable Learning” in Munich, Germany.

Weyringer, S. (2008). Die Anwendung von VaKE in internationalen Sommercamps für besonders begabte Jugendliche [Applying VaKE in international summer camps for particularly gifted students] (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Universität Salzburg, Austria.

Weyringer, S., Patry, J.-L., & Weinberger, A. (2012). Values and knowledge education. Experiences with teacher trainings. In D. Alt & R. Reingold (Eds.), Changes in teachers’ moral role. From passive observers to moral and democratic leaders (pp. 165–197). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Weyringer, S., Patry, J.-L., Weinberger, A. & Nussbaumer, M. (2013). Values and Knowledge Education (VaKE). In H. Ganthaler, C. R. Menzel & E. Morscher (Hrsg.) Aktuelle Probleme und Grundlagenfragen der Medizinischen Ethik (S. 155–201) [Current problems and fundamental questions in medical ethics]. Sankt Augustin: Academia.

Willemse, M., Lunenberg, M., & Korthagen, F. (2008). The moral aspects of teacher educator’s practices. Journal of Moral Education, 37(4), 445–466.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) (TRP 56-G17) and the Austrian Federal Ministery of Education an Women's Affairs (BMUKK 20.040/0014-I/7/2011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Weinberger, A., Patry, JL. & Weyringer, S. Improving Professional Practice through Practice-Based Research: VaKE (Values and Knowledge Education) in University-Based Teacher Education. Vocations and Learning 9, 63–84 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-015-9141-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-015-9141-4