Abstract

The aim of the present study was to (i) develop a material affluence scale (MAS) for measuring adolescent SES in health inequality research in developing countries, (ii) compare the association of the MAS with the parental SES measures (parental occupation and education), and (iii) evaluate the association of parental SES and MAS with key health and health behaviour indicators. We used school-based cross-sectional survey conducted in thirty districts within three administrative regions in southern Ghana (a West African country) among adolescents ages 12–18-year old (N = 1,195) as an example. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used as the main statistical technique. MAS categorised adolescents into material affluence groups (MAS scores for the poorest, poor, average, affluent and most affluent were−1.679, −0.355, 0.354, 0.725 and 1.022 from the first principal component quintile respectively), it has adequate internal coherence (α = 0.622) and moderately correlates with parental SES (r = 0.39, p < 0.001). MAS and parental SES showed similar pattern of strength and direction of association with selected health and health behaviour indicators. MAS presents a viable alternative method for measuring adolescent’s SES in health inequality research in developing countries and could be useful as well in western countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Research in health inequalities among adolescents has increased in recent decades (Currie et al. 1997; Wardle et al. 2004; Koivusilta et al. 2006; Marmot 2005, West 1997). Traditionally, epidemiological studies have used the educational attainment, occupational status and income as the measures of socioeconomic status (Galobardes et al. 2006a, b). These three measures were assumed to measure a wide range of social factors which could account for disparities in health (Galobardes et al. 2006a, b; Durkin et al. 1994).

Concerning adolescents, there have been problems in collecting data on the parental income, occupation and education from adolescents partly because they are unable to provide accurate information on their parents or sometimes unwilling to do so (Currie et al. 1997; Molcho et al. 2007). Consequently, surveys involving obtaining parental SES information from adolescents have resulted in large proportions of missing data (Currie et al. 1997; Molcho et al. 2007; Wardle et al. 2004). This has led to a rising interest in exploring non-parental measures of adolescent SES in health research (Currie et al. 1997; Wardle et al. 2004; Koivusilta et al. 2006; Molcho et al. 2007).

The development of the Family Affluence Scale (FAS) by Currie et al. (1997) in the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) study based on the earlier works of Townsend (1987) and Carstairs and Morris (1991) was a significant road map in researching adolescents’ SES in the health sciences in the western countries. FAS seeks to address the difficulties involved in obtaining SES information from adolescents which often resulted in misclassification and particularly low completion rates. FAS uses simple multiple indicators measured by non-sensitive questions which are relevant to the setting and reflect the family affluence in a household (Currie et al. 1997). Initially, items on the FAS were: the number of telephones in the household, the number of cars in the family, and having own unshared bedroom (Currie et al. 1997). Later, FASI and FASII were developed and the items on the scale were modified to include the number of family holidays and the number of computers in the family while the number of telephones was removed (Currie et al. 2004; Boyce and Dallago 2004; Mullan and Currie 2000).

Research has increased on the inequalities in health among adolescents in recent years. However, studies conducted so far are from western countries, Europe and America (Durkin et al. 1994; Alvarez-Dardet 2000; Morris et al. 2000; Currie et al. 2004, Boyce and Dallago 2004; Mullan and Currie 2000; Currie et al. 2008). Admittedly, the SES is not a static concept but varies according to culture, social structure of the society and in different economic settings (Wardle et al. 2004; Currie et al. 2004). In the developing world, there are many difficulties involved in measuring the socioeconomic status owing to the inappropriateness of the indicators used, their non-applicability across the culturally and economically diverse nature of the society. The few studies on SES among adults in developing countries used indicators such as type and material of housing, source of drinking water, sewage system, type of domestic fuel, land ownership, education, occupation, living conditions, and demographic conditions (Crontinovis et al. 1993; Durkin et al. 1994; Fiadzo et al. 2001; Galobardes et al. 2006a, b). Even among adults obtaining information on these indicators poses a great challenge (Durkin et al. 1994). Regarding adolescents, SES and its association with health outcomes and health behaviours have been hugely understudied in the developing world, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, despite the revelation that inequalities in health have widened over the years (World Bank 2006).

2 The Theoretical Framework

Our concept of material deprivation is based on the work by Townsend (1987). According to Townsend, “Deprivation takes many different forms in every known society. People can be said to be deprived if they lack the types of diet, clothing, housing, household facilities and fuel and environmental, educational, working and social conditions, activities and facilities which are customary, or at least widely encouraged and approved, in the societies to which they belong.” Material deprivation is perceived as the lack of the resources and goods necessary for descent living in relation to what is generally available in the society. Individuals who are materially deprived may encounter conditions that may be detrimental to their health, for example poor diet, inaccessibility to health care, poor environmental conditions, health damaging behaviours such as smoking and sedentary behaviours as well as stress due to the shame and humiliation associated with the deprivation. We employed a wide range of indicators which capture the key aspects of wealth as well as the material circumstances to investigate the underlying structure of familial material circumstances of adolescents.

The aim of the present study was to develop a material affluence scale (MAS) that could be used to measure the socioeconomic status of adolescents in health inequality research in developing countries, compare the scale to be constructed with the traditional measures of SES (parental education and occupation) and test its association with key health and health behaviour indicators. We used a school-based survey data from Ghana, a West African country, as an example.

3 Method

3.1 Data

This study is based on a cross-sectional survey on health behaviours and lifestyles of school-aged adolescents in three administrative regions in southern Ghana. The data were collected from June to August 2008.

3.1.1 Sample

The sample comprised of thirty stratified random sample schools, ten per region, from each of three sampled regions in southern Ghana, (Eastern, Greater Accra and Volta Regions of Ghana). The Ghana Education Service’s School Health Education Programme register of schools in the country was the source of the sampled schools. A letter of support obtained from the Ministry of Education School Health Education Programme unit was sent to the schools.

The schools were selected so that they comprised of four public Junior High Schools, two private Junior High Schools, three public Senior High Schools and one private Senior High School in each region in order to reflect the school types in the country. In each school, one or two classes of about fifty students were selected at random. All students whose names were found in the class attendance register of the selected classes were eligible to participate in the survey. The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of the Ghana Health Service Research Unit in Accra, Ghana.

3.1.2 Sample Size and Response Rate

The characteristics of the respondents according to age, gender and school type are presented in Table 1. In all, 1,195 out of the 1,566 respondents who completed the questionnaire have been used in this study. We excluded those outside the age 12–18-years. The response rate was 89.7% (based on academic year’s register), it was not clear whether those absent had stopped schooling or were just absent. Only one pupil denied answering.

3.1.3 Questionnaire Administration

The eight page questionnaire was anonymous and self-administered. It was designed to exclude any information that will reveal the identities of the participants.

One trained supervisor was assigned to each classroom during the answering. The survey commenced simultaneously in all the participating classes in a given school. Participants were asked to drop their questionnaires in an envelope placed in front of the class on completion. In two of the rural schools, the students could not understand the questions so it was translated into the local language by a teacher (in one school) and by the principal investigator in the other school. Also, in one of the remote public schools the Junior High School (JHS) was not in session as the teachers did not come to school due to lack of transportation to school on the survey day hence the primary six pupils (they were supposed to be in JHS in the following 2 months when new academic year begins) were selected to replace the absent JHS. The three schools altogether constitute only 4.3% of total respondents, besides the responses of these schools were not different from the others hence they were included in the analysis. For simplicity, we added the primary six respondents (N = 26) to the junior high school respondents in Table 1.

3.1.4 Socioeconomic Indicators

Parental SES (Parental Education and Occupation)

Parental educational status was measured by the questions “What is your father’s/guardian’s highest level of education?” and “What is your mother’s highest level of education?” The respondents were asked to choose from, ‘no education’, ‘primary school’, ‘middle school/JSS’, ‘O’level/SSS’, ‘technical/vocational school’, ‘A’level’, ‘university’ and ‘other’. They were to mention the level of education if they chose ‘other’ (unknown) as the answer. The responses were coded (0–3) into illiterate, basic education, secondary education and tertiary education according to the classification of the Ghanaian educational system. Parental occupational status was measured using the questions, “What is your father’s/guardian’s occupation?” and “What is your mother’s occupation?” Pupils were asked to choose one of the following; ‘unemployed’, ‘farming’, ‘fishing’, ‘carpentry’, ‘driver’, ‘selling’, ‘dress making/tailoring’, ‘hair dressing’, ‘secretary’, ‘accountant’, ‘office work’, ‘teaching’, ‘manager/director’, and ‘other’. They were asked to mention what kind of work if they chose ‘office work`, manager/director or ‘other’ as response. The responses were then condensed into six categories: unemployed, (unknown), grade E, grade D, grade C and grade B) according to the occupational classification in the Ghanaian civil service (Head of Civil Service 2000): A, chief in rank; B, professional and managerial; C, professional non managerial; D, skilled manual; and E, unskilled manual. None of the respondents fell into the A category. This was further coded 0–4, excluding the unknown category. We computed parental SES by summing up the scores for parental education and occupation to produce a composite scale (0–18) which was further categorised into three referred herein as low (0–8), middle (9–10) and high (11–18) parental SES for those who completed both questions.

3.1.5 Material Affluence Indicators

Adolescent material affluence was measured by twenty one indicators made up of three broad categories; household assets and housing characteristics; other assets; and school related indicators.

Household Assets and Housing Characteristics

The questions were as follows: “Which of the following home appliances does your parent(s) or guardian have at home?” You can choose more than one answer. Options: 1 = Computer, 2 = Television, 3 = Fridge/Freezer, 4 = Radio, 5 = Other, what? Dichotomous response variable (0, 1) was created for each response; “Do you have electricity at home?” (0 = no, 1 = yes); “How many cars does your family have/own?” Options :(0 = no, 1 = yes, 2 = two cars, 3 = three or more cars) recoded 0 = no car, 1 = one or more cars; “Is the house you live in owned by your parent(s) or guardian?” 0 = no, 1 = yes; “Do you have your own room?” 0 = no, 1 = yes; “How many people do you sleep with in the same room?” Write the number:... Recoded: 0 = less than three, 1 = more than three persons per room; “Which of the following best describes the house where you live?” Options:1 = Mud/bamboo/wood house with thatch roofing, 2 = Mud/bamboo/wood house with sheet roofing, 3 = Uncemented block house, 4 = Block house cemented and painted, 5 = Other, what? We coded ‘other’ into the appropriate categories. Recoded 0 = non-block house (responses 1, 2 and 3), 1 = block house (response 4).

Other Assets

The questions were as follows: “Which of the following other properties do your parent(s) or guardian has? You can choose more than one answer”. Options: 1. = Store/shop, 2 = Cocoa farm, 3 = Oil palm farm/plantation, 4 = Mango farm, 5 = Cattle/Sheep/Goats (more than ten), 6 = Corn mill machine/Tractor, 7 = Factory, 8 = Other, what?...Dichotomous response variable was created for each response.

3.1.6 School Related Indicators

The questions were as follows: “Do you work in the morning before going to school?” Options: 0 = no; “Do you work when you close from school?” coded 0 = no, 1 = yes); “Do you have a private teacher?” Options 1 = yes, 2 = no, 3 = I had in the past but not now, recoded 2 as 0 = never had, 1and 3 as 1 = ever had; “How many of your brothers and sisters are of school-going age (6–15 years) but are not in school?” Write the number, recoded as 0 = none, 1 = one or more. We clarified to the respondents that: working before and school refers to any work apart from normal household chores such as sweeping the compound and fetching water into the pot in the morning before going to school or in the evening when school closes.

3.1.7 Indicators of Health and Health Behaviours

Self-rated health at the time of inquiry was measured by the question, “How do you describe your health in general?” Options: ‘excellent’, ‘very good’, ‘good’, ‘fair’, and ‘poor’. These were collapsed into, ‘poor’(‘fair’ and ‘poor’) and ‘good’ (‘excellent’, ‘very good’ and ‘good’) self-rated health.

Fruit in-take was measured by: “During the past 1 week (7 days), on how many days did you usually eat fruit, such as oranges, pineapple, watermelon, banana, guava, pear, sweet apple, mangoes, or pawpaw?” Options: ‘not once’, ‘1–3 days’, ‘4–6 days’, and ‘everyday’. These were dichotomised into categories ‘rarely’ (not once and 1–3 days) and ‘often’ (4–6 days and everyday).

Fried food in-take was measured by: “During the past 7 days on how many days did you usually eat fried foods?” Options: ‘not once’; ‘1–3 days’; ‘4–6 days’; and ‘everyday’. The responses were recoded into dichotomous responses, ‘rarely’ (not once and 1–3 days) and ‘often’ (4–6 days and everyday).

Teeth brushing was assessed by: “How often do you clean/brush your teeth?” ‘never’, ‘about once a week or less often’, ‘2 to 3 times a week’, ‘about 4 to 5 times a day or more’, ‘about once a day’, ‘about 2 to 3 times a day or more’ were the alternatives given. These were categorised into ‘less than daily’ and ‘daily’.

Physical activity was investigated by: “How physically active are you?” Options: ‘not physically active’, ‘a little physically active’, ‘physically active’ and ‘very physically active’ were recoded into dichotomous responses, ‘less physically active’ (not physically active, a little physically active) and physically active’ (physically active and very physically active).

3.1.8 Statistical Analysis

Construction of the Material Affluence Scale (MAS)

We employed the statistical method of principal component analysis (PCA) to determine the weight of each indicator on the material affluence scale. PCA is a multivariate statistical technique which is capable of reducing a set of variables in a data set into smaller number of dimensions. It has the ability to describe the variation of a set of variables as a set of linear combinations of the original variables, so that successive linear combinations which explain most of the variation in the original data are extracted.

In constructing the scale, we excluded the indicators “mango farm”, “Corn mill machine/tractor” and “Factory” due to extremely low ownership of these items in the study population (both rural/urban and in regions). When we included these items the Cronbach’s alpha was below 0.5 and Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was less than the recommended 0.6, indicating non-internal consistency of the indicators meaning that they cannot be on a summated scale. Initial screening of the remaining eighteen material indicators was done as follows. Overcrowding was excluded because of having communality less than 0.3, (Pett et al. 2003; Pallant 2007). Sheep/goats, store/shop, cocoa farm, oil palm farm/plantation, working in the morning before going to school, working in the evening after school, having siblings who were of school going age but are out of school and having a private teacher were excluded because they had extremely low inter-item correlation, < 0.1, with all the indicators on the scale (Pett et al. 2003; Pallant 2007). The nine remaining indicators (fridge/freezer, television, radio, computer, electricity, car, house ownership, own bedroom and block house) were then subjected to the final Principal Component Analysis (PCA) model using SPSS version 16. The first, second and third eigenvalues were 2.59 1.42 and 1.11 respectively. The Kaiser-Meyer-Oiklin value was 0.727, exceeding the recommendation value of 0.6 and the Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity reached statistical significance (p < 0.001).

The associations between variables were tested using chi-square tests and Spearman correlations. Cronbach’s alpha was computed to assess the internal consistency reliability of the scale. Logistic regression analysis was used for bivariate and multivariate analyses of the association between parental SES, MAS and health and health behaviour indicators.

4 Results

4.1 Missing Values

A large number of adolescents were unable to neither provide their parental education and occupation nor give sufficient information on these indicators that could enable us to classify them into the appropriate categories. This has resulted in relative large missing values. On the other hand, there was very high completion rate for the material affluence indicators. All adolescents were able to report whether or not their parents own fridge/freezer, Television set and computer (Table 2).

No statistically significant differences were found in the parental SES completion rate by material affluence scale, age and gender (p = 0.110, p = 0.263, p = 0.110, p = 0.510 respectively). Girls had slightly higher completion rates for maternal occupation (p = 0.039) than boys. Likewise boys had slightly higher completion rates for paternal occupation (p = 0.043) than girls. We did not find such statistically significant gender differences by paternal and maternal education (p = 0.758 and p = 0.559). No statistically significant differences in the completion rates by age and gender were found for the questions that assessed the material indicators (p = 0.531, and p = 0.238 respectively). Over all, only 80.7% of the adolescents completed parental SES measures information compared to 94.2% completion rate for the material affluence indicators. It implies that 13.5 of those who could not provide information on the parental SES measures were able to provide information on the material affluence indicators.

4.2 Material Affluence Scale (MAS)

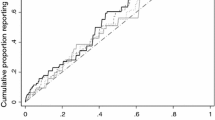

The principal component analysis revealed the presence of three components with eigenvalues exceeding 1, explaining 28.7%, 15.8% and 12.3% respectively of variance. As the percentage of adolescent with missing data was relatively low (5.8% for MAS indicators combined) inclusion or exclusion of the missing case did not change the association between MAS and the health and health behaviours so the missing cases for each indicator were excluded pairwisely. The Cronbach’s alpha for nine indicators was 0.622, indicating internal consistency of the indicators and justifying their use in a summated scale.

For the purposes of this study the first principal component was assumed to be the measure of material affluence because it summaries the largest amount of information common to all the indicators. Table 3 shows the factor scoring from the first principal component analysis of the nine indicators. Fridge/freezer ownership (0.749) and house ownership (0.074) were assigned the highest and lowest scores respectively. The higher the weight of an item the more relevant it is on the scale. Household with more assets would obtain a higher score on the MAS and vice versa. Ownership of fridge/freezer, television, car, having electricity at home, and living in a block house showed consistent trend across the material scale affluence quintiles.

The first principal component was divided into quintiles, so that adolescents were classified as poorest, poor, average, affluent and most affluent in terms of the material status.

Over all, the differences were wider between the lower MAS groups than the upper groups. The differences in the mean scores of the material affluence scale between the groups by urbanisation level and region of residence are similar to those observed in the total population (Table 4).

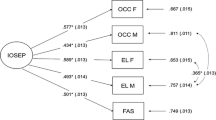

4.3 Association Between the Material Affluence Scale and Parental SES Indicators

The association of MAS quintiles with parental occupation and education are presented in Table 5. The material affluence scale (MAS) was modestly correlated with the parental SES (r = 0.32; 0.36; 0.17 and 0.29 for maternal education, paternal education, maternal occupation and paternal occupation respectively, all at p < 0.001). The scale explained 14% of the variance in the parental SES when all the four parental SES indicators were combined (r = 0.39, p < 0.001).

4.4 Relationship Between the Scale and Health/Health Behaviour Indicators

We investigated the ability of the scale to predict key health and health behaviour indicators in comparison to the parental SES measures. The results are presented in Table 6.

The parental SES and MAS showed very similar pattern of strength and direction of association for all the health and health behaviour indicators. There were positive associations between high SES (both parental and material affluence scale) and physical activity, good self-rated health and daily teeth brushing. The associations between both measures of SES and fruit in-take and fried food in-take were not statistically significant.

5 Discussion

5.1 Summary and Interpretation of Results

In this study, a material affluence scale (MAS) was constructed using material affluence indicators which represent material living conditions in Ghanaian adolescents’ reality. Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to reduce eighteen material affluence indicators to nine to construct the MAS. The first principal component had adequate internal coherence and moderately correlated with parental SES measures. The MAS and parental SES showed similar pattern of strength and direction of association with key indicators of health and health behaviours suggesting that MAS presents a viable alternative method for measuring adolescents’ SES in health inequality research in developing countries and could as well be used in western countries.

5.2 The Construction of the Material Affluence Scale (MAS)

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was employed as a statistical technique to determine the weight of each variable on the MAS. The World Bank commonly uses PCA in the construction of its asset based socioeconomic indices which are often used in assessing health differences within and between countries (Gwatkin et al. 2000). Many other studies have also used PCA to construct socioeconomic indices for measuring inequality (Filmer and Pritchett 2001; Houweling et al. 2003; Schellenberg et al. 2003; Vyvas and Kumaranyake 2006). The overriding advantage of the PCA method used here is that, it determined the weights of the variables in the scale and thus gave an ‘objective’ contribution of each variable to the scale constructed. In scale construction using PCA, usually the first principal component is considered to be the scale as we did here too (Filmer and Pritchett 2001; Houweling et al. 2003; Vyvas and Kumaranyake 2006). Studies using PCA commonly use arbitrary cut-off points; the lowest 40% classified as poor, the highest 20% as rich and the rest as middle group. Others also divide the subjects into quintiles (Filmer and Pritchett 2001; Gwatkin et al 2000). Both approaches are arbitrary, yet they yielded similar correlation with the parental SES (r = 0.35 and r = 0.39 respectively, p < 0.001 for both) as well as similar pattern of association with the health and health behaviour indicators as reported in previous research (Filmer and Pritchett 2001). We employed the quintile approach in this study, based on the assumption that SES is uniformly distributed. Some studies found negative principal scores for ownership of certain material indicators (Gwatkin et al. 2000; Houweling et al. 2003) implying that such items were associated with lower SES. However, in this study all the items yielded positive scores meaning their ownership indicated material advantage and consistent with those reported in some previous studies (Schellenberg et al. 2003; Sahn and Stifel 2003; Vyvas and Kumaranyake 2006). Similar pattern of scores were found when the analysis was done separately for rural, urban and region of residence confirming that these assets represent wealth in the study population irrespective of urbanization level or region.

We used housing characteristics (block house, house ownership, whether adolescents have their own bedrooms) and availability of amenities and movable properties (fridge/freezer, television, radio, computer and car) to assess material circumstance. These housing characteristics and household assets used in this study are not only markers of material circumstances but may also be related with some mechanisms of health. For instance, overcrowding can aid the spread of infectious disease. These indicators are particularly useful in adolescent survey because questions relating to these are relatively easy to answer by them as they represent reality in adolescents’ lives. However, one major limitation is that these indicators could be setting specific and might need modifications when applied in other settings. Electricity, for example, can be classified as a consumer as well as capital good. It is in one way related to expenditure but on the other hand it could be regarded as a measure of deprivation of home facilities (Townsend 1987) because its availability or otherwise could be an indication of the material circumstances of the family and in a wider perspective it could be a proxy for the measure of the neighbourhood characteristics. These consumer and capital goods are proxy for income and therefore have a direct effect on material resources. Income affect the quality of resources, access to services (e.g. health care) boost self-esteem and is linked to behaviour. In a developing country where information on income may not be available, and especially in adolescent survey these indicators could be useful proxy for income inflow and outflow-material circumstance of households in general.

There was no clear trend across the quintiles for the indicators; house ownership, radio, computer and having adolescent’s own bedroom. In Ghana ownership of a house is not as important as the type of house because in the rural areas folks can own many mud houses but this might not necessarily measure wealth since living in a rented apartment could even be more prestigious than owning a mud house. We examined the mean MAS scores by rural/urban and found higher house ownership among those in the lower quintile consistently across but not in the urban setting. This also could explain the not clear trend in the scores for house ownership and having own bedroom. The inconsistent trend in the scores for radio and computer ownership across the material affluence quintile could be contributable to the relatively high ownership of radio and the rare ownership of computer in the study population.

An alternative method commonly used for scale construction is the arbitrary approach of assigning equal weights to each variable and simply summing them up (Currie et al. 1997; Montgomery et al. 2000; Morris et al. 2000; Wardle et al. 2004). One major pitfall of this arbitrary method is that it cannot be used for exploratory analysis involving data reduction and hence only suitable where few indicators are measured. In addition, it does not show the contribution of the individual indicators to the scale.

5.3 Reliability of the Indicators Used for the Construction of MAS

It has been recommended that the measures of SES should be setting specific and relevant at the time of the study (Currie et al. 2004). All the same, almost all the eighteen indicators that we measured have been measured and used in the construction of SES index in the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) in developing countries (see e.g. Crontinovis et al. 1993; Durkin, et al. 1994; Filmer and Pritchett 2001; Houweling et al. 2003; Vyvas and Kumaranyake 2006). Studies from the DHS surveys are comparable both across and within countries. Besides, the point we seek to make is that the nine indicators which were retained in the PCA and in the MAS could be useful measures of adolescent’s material circumstances in studies where measuring parental education, occupation and income poses a problem.

5.4 External Validity of the Material Affluence Scale (MAS)

To assess the external validity of the MAS, we examined it association with the traditional measures (parental SES) commonly used in adolescents health inequality research (Currie et al. 1997; Wardle et al. 2002). The first principal component had adequate internal coherence and moderately correlated with parental SES measures but highly statistically significant. As socioeconomic status is a multidimensional and complex construct, it is unlikely that examining the association between alternative measures would produce high correlation because different indices of SES measure different aspects of the phenomenon. Studies comparing parental SES and other scales found pretty similar results as ours (Currie et al. 1997; Wardle et al. 2002). Parental education is linked to adolescents (who are generally considered as dependants) in the family. It reflects not only the material resources but also intellectual and other resources of the family of origin. The effects of parental education on both adolescence and adult life on health and health behaviours have been well established (e.g. Koivusilta et al. 2006). Similarly, parental occupation affects adolescent’s health and behaviour at different stages of the life course. Indeed, occupation is strongly related to income and thus may affect in similar ways as material resources and as well proxy for living standard and health among others. One major limitation of parental education and occupation in adolescent survey is the inability of the respondents to produce relevant and sufficient information which can be useful in classifying them into parental educational and occupational categories. This often results in high missing data in adolescent surveys. Previous studies indicates that there are difficulties in obtaining information on the parental education, occupation and income from adolescents leading to a growing interest in exploring other alternative measures of adolescents’ SES (Currie et al. 1997; Wardle et al. 2004; Molcho et al. 2007). In this study, completion rate was relatively high for all the variables measured, still over all, the parental occupation and education indicators scored comparatively low completion rate compared to the material indicators as observed in other studies (Currie et al. 1997; Wardle et al. 2004; Molcho et al. 2007). This suggests that MAS could be an important took not only in developing countries but could also be used in the western countries where obtaining parental SES information possess a problem.

5.5 Relationship Between the Material Affluence Scale and Health/Health 454 Behaviour Indicators

The MAS and parental SES showed similar pattern of strength and direction of association with selected indicators of health and health behaviours suggesting that MAS and parental SES were distinct yet related scales measuring various aspects of a multidimensional phenomenon. The findings of similar pattern of association between parental SES and the MAS for all the health and health behaviour indicators used in this study further suggest that MAS presents an authentic alternative for parental SES (parental occupation and education) where obtaining the latter gives more missing values and coding of occupation is time consuming and expensive.

5.6 Study Limitations and Further Research

This study is not a call to discard the traditional SES measures in adolescent survey neither do we claim that the MAS developed is the optimal method for measuring adolescents material circumstance in health and health behaviour inequality research. The point of this study is to add knowledge to measuring SES of adolescents in developing countries and as well motivate further discussions on the subject.

Owing to resource constrains, only adolescents in schools have been included in this study hence the results herein reported might not necessarily be same in the entire adolescent population. However, a sample of 127 non-students in the same age group showed similar pattern of responses not only for the material indicators but also for most of the key indicators we measured in our survey. Besides, the school enrolment rate in Ghana for the age group of our respondents is relatively high-78.8% for Junior High Schools (Ministry of Education, Science and Sport, Ghana, 2008).

Regarding the household indicators, it would have been interesting to include the indicators that measure water and sanitation conditions of the household, on the other hand, these indicators highly correlate with electricity hence the non-inclusion of the water and sanitation variable is not likely to affect the result.

We neither considered the reliability of the health and health behaviour indicators nor the parental and material indicators used in this study. However, regarding the use of PCA, validation study from Indonesia, Pakistan and Nepal showed that scale constructed from PCA had good prediction of school enrollment disparities as the other more conventional approaches (Filmer and Pritchett 2001). Nonetheless, one obvious limitation of the use of the PCA is that it leads to lose of information due to summary coding of responses but this was necessary for easy interpretation of the weights (Filmer and Pritchett 2001). Validation study which examines inter-rater and test-retest reliability on these indicators among adolescents in developing countries would give more insight into researching adolescent’s health in such countries. Future studies wishing to use similar approach used in this study must bear in mind the need to consider material affluence indicators that are applicable to the study setting and also relevant at the time of study.

6 Conclusions

The debate on both the search for a more appropriate measure of adolescents SES as well as the method for measuring socioeconomic status in general is still ongoing. Many studies have highlighted the issue of low completion rates and inappropriate responses of the traditional SES indicators in adolescent surveys mainly, in western countries. Material indicators have relatively higher completion rates compared to parental SES indicators (parental occupation and education). PCA is an easy statistical technique that has an advantage of using data that is relatively easy to answer in adolescent survey, because they represent facts in adolescent’s reality, and as well uses many variables in reducing the dimensionality of the data, compared to other statistical methods, to construct material affluence scale. Material affluence scale constructed in this study has adequate internal coherence and good external validity when compared with the traditional SES measures (parental education and occupation). The material affluence scale was similar to the parental SES in terms of their strength and direction of association with health/health behaviour indicators. MAS presents an authentic alternative method for measuring adolescents SES where that latter is unavailable or difficult to obtain, particular in developing countries.

References

Alvarez-Dardet, C. (2000). Measuring inequalities in health in Africa. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 54, 321.

Boyce, W., & Dallago, L. (2004). Socioeconomic inequality. In WHO. (Ed.), Young people’s health in context. Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study: international report from the 2001/2002 survey.

Carstairs, V., & Morris, R. (1991). Deprivation and health in Scotland. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press.

Crontinovis, I., Vella, V., & Ndiku, J. (1993). Construction of a socioeconomic index to facilitate analysis of health of health data in developing countries. Social Science and Medicine, 36(8), 1087–1097.

Currie, C. E., Elton, R. A., Todd, J., & Platt, S. (1997). Indicators of socioeconomic status for adolescents: the WHO Health Behaviour in school-aged children survey. Health Education Research, 12(3), 385–397.

Currie, C. R., Morgan, A., Smith, R., Settertobulte, W., Samdal, O., et al. (2004). Young people’s health in context. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

Currie, C., Molcho, M., Boyce, W., Holstein, B., Torsheim, T., & Richter, M. (2008). Researching health inequalities in adolescents: the development of the Health Behaviour in School—Aged Children (HBSC). Social Science & Medicine, 6, 1429–1436.

Durkin, M. S., Islam, S., Hasan, Z. M., & Zaman, S. S. (1994). Measures of socioeconomic status for child health research: comparative results from Bangladesh and Pakistan. Social Science & Medicine, 38, 1289–1297.

Fiadzo, E. D., Houston, J. E., & Godwin, D. D. (2001). Estimating housing quality for poverty and development policy analysis: CWIQ in Ghana. Social Indicators Research, 53(2), 137–162.

Filmer, D., & Pritchett, L. H. (2001). Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data—or tears: an application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography, 38, 115–132.

Galobardes, B., Shaw, M., Lawlor, D. A., Lynch, J. W., & Smith, G. (2006a). Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 2). Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60, 95–101.

Galobardes, B., Shaw, M., Lawlor, D. A., Lynch, J. W., & Smith, G. (2006b). Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60, 7–12.

Gwatkin, D. R., Rustein, S., Johnson, K., Pande, R., & Wagstaff, A., (2000). Socioeconomic differences in Nigeria. Health, Nutrition, and Population in Nigeria. Washington, DC: HNP/poverty Thematic Group of the World Bank. www.worldbank.org/poverty/health/data/index.htm#lcr.

Houweling, T. A. J., Kunst, A. E., & Mackenbach, J. P. (2003). Measuring health inequality among children in developing countries: does the choice of the indicator of economic status matter? International Journal for Equity in Health, 2, 8.

Koivusilta, L. K., Rimpelä, A. H., & Kautiainen, S. M. (2006). Health inequality in adolescence: does stratification occur by familial social background, family affluence, or personal social position? BMC Public health, 6, 110.

Marmot, M. G. (2005). Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet, 365, 1099–1104.

Ministry of Education, Science and Sport, Ghana. (2008). Reports on basic statistics and planning parameters for basic education in Ghana 2007/2008 EMIS project, page 16.

Molcho, M., Nic Gabhainn, S., & Kelleher, C. (2007). Assessing the use of the family affluence scale (FAS) among Irish schoolchildren. Irish Medical Journal, 100(8), 37–39.

Montgomery, M. R., Gragnolati, M., Burke, K. A., & Paredes, E. (2000). Measuring living standards with proxy variables. Demography, 37(2), 155–174.

Morris, S. S., Calogero, C., Hoddinot, J., & Christiaensen, L. J. M. (2000). Validity of rapid estimates of household wealth and income for health surveys in rural Africa. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 54, 381–387.

Mullan, E., & Currie, C. (2000). Socioeconomic inequalities in adolescent health. In WHO (Ed.), Health and health behaviour among young people. Health policy for children and adolescents issue 1, 65–72.

Pallant, J. (2007). SPSS survival manual: a step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS for windows third edition. Open University Press, 179–2000.

Pett, M. A., Lackey, N. R., & Sullivan, J. J. (2003). Making sense of factor analysis. The use of factor analysis for instrument development in health care research. SAGE.

Sahn, D., & Stifel, D. (2003). Exploring alternative measures of welfare in the absence of expenditure data. Review of Income and Wealth, 49, 463–489.

Schellenberg, J. A., Victora, C. G., Mushi, A., Savigny, D., Schellenberg, D., Mshinda, H., et al. (2003). Inequities among the very poor: health care for children in southern Tanzania. The Lancet, 361, 561–566.

Townsend, P. (1987). Deprivation. Journal of Social Policy, 16, 125–146.

Vyvas, S., & Kumaranyake, L. (2006). How to do (or not to do)…Constructing scocio-economic status indices: how to use principal components analysis. Health Policy and Planning, 6, 459–468.

Wardle, J., Robb, K., & Johnson, F. (2002). Assessing socio-economic status in adolescents: the validity of a home affluence scale. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 56, 595–599.

Wardle, J., Robb, K. A., Johnson, F., Griffith, J., Power, C., Brummer, E., et al. (2004). Socioeconomic variation in attitudes to eating and weight in female adolescents. Health Psychology, 23(3), 275–282.

West, P. (1997). Health inequalities in the early years: is there equalisation in youth? Social Science & Medicine, 44, 833–858.

World Bank. World Development Report (2006): Equity and Development: Overview,Partonehttp://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTWDR2006/Resources/477383-1127230817535/082136412X.pdf.

Acknowledgements

The study was financially supported by the Finnish Cultural Foundation Central Fund, Tampere University research stipend and the Competitive Research Funding of the Pirkanmaa Hospital District, Tampere University Hospital. We would like to thank Mr. Charles Fenuku, Mr. Akuffo, Miss Forzia, Miss Tani Abubakari, Miss Rejoice Nutakor, Mrs. Cynthia Bosumtwi-Sam, Mr. Francis Kpodo and his team for assisting in data collection and entry. We thank Mr. Lasse Pere for data management. Many thanks to the NTTT research group at the Tampere School of Public Health, University of Tampere, for their valuable contributions during the drafting and revising of the questionnaire.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Doku, D., Koivusilta, L. & Rimpelä, A. Indicators for Measuring Material Affluence of Adolescents in Health Inequality Research in Developing Countries. Child Ind Res 3, 243–260 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-009-9045-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-009-9045-7