Abstract

This study aimed to analyze the seed potato systems in Ethiopia, identify constraints and prioritize improvement options, combining desk research, rapid appraisal and formal surveys, expert elicitation, field observations and local knowledge. In Ethiopia, informal, alternative and formal seed systems co-exist. The informal system, with low quality seed, is dominant. The formal system is too small to contribute significantly to improve that situation. The informal seed system should prioritize improving seed quality by increasing awareness and skills of farmers, improving seed tuber quality of early generations and market access. The alternative and formal seed systems should prioritize improving the production capacity of quality seed by availing new varieties, designing quality control methods and improving farmer’s awareness. To improve overall seed potato supply in Ethiopia, experts postulated co-existence and linkage of the three seed systems and development of self-regulation and self-certification in the informal, alternative and formal cooperative seed potato systems.

Resumen

Este estudio tuvo el propósito de analizar los sistemas de producción de papa en Etiopia, identificar limitantes, y priorizar opciones de mejorar, mediante la combinación de investigación de escritorio, apreciaciones rápidas y estudios formales, encuestas a expertos, observaciones de campo y conocimiento local. En Etiopia co-existen sistemas de semilla informal, alternativo y formal. Domina el sistema informal, con baja calidad de semilla. El sistema formal es muy pequeño como para contribuir significativamente al mejoramiento de esa situación. El sistema informal de semilla debería tener como prioridad el mejoramiento en la calidad de la semilla mediante el aumento en la atención y habilidades de los productores, mejorando la calidad de la semilla-tubérculo de las generaciones tempranas y el acceso al mercado. Los sistemas alternativo y formal de semilla deberían priorizar el mejoramiento en la capacidad de producción de semilla de calidad, mediante la validación de nuevas variedades, el diseño de métodos de control de calidad, y mejorando la atención del productor. Para mejorar el suministro general de semilla de papa en Etiopia, los expertos postularon la co-existencia y asociación de los tres sistemas de semillas y el desarrollo de autorregulación y autocertificación en los sistemas cooperativos de semilla de papa informal, alternativo y formal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) is one of the tuber crops grown in Ethiopia. It is grown by approximately 1 million farmers (CSA 2008/2009). Potato is regarded a high-potential food security crop because of its ability to provide a high yield of high-quality product per unit input with a shorter crop cycle (mostly < 120 days) than major cereal crops like maize. Recently the price of cereals strongly increased world wide and in Ethiopia the price subsequently stabilized at a high level, whereas the price of roots and tubers remained relatively low during the entire food crisis. This shows that there is room for added value in the chain of tuber crops. Potato can potentially be grown on about 70% of the 10 Mha of arable land in the country (FAO 2008). There are improved varieties that yield 19–38 Mg ha−1 on farmers’ fields (Gebremedhin et al. 2008). However, the current area cropped with potato (about 0.16 Mha) is small and the average yield (less than 10 Mg ha−1) is far below the potential. The low acreage and yield are attributed to many factors, but lack of high-quality seed potatoes is a major factor (Lemaga et al. 1994; Endale et al. 2008a; Gildemacher et al. 2009a). Ethiopia is a land-locked, poor country with a negative trade balance, which makes expensive imports of high-quality seed tubers from Europe or elsewhere unaffordable.

Increase in potato acreage and yield calls for improvement of the quality of seed potatoes supplied to the ware potato production systems.Footnote 1 This requires the improvement of the seed potato systems operating in the country. To suggest options for improvement, knowledge on the current status and performance of seed potato systems is essential. Some studies have been undertaken on seed potato production in different parts of Ethiopia (e.g., Mulatu et al. 2005a; Guenthner 2006; Gildemacher et al. 2009b). These studies, however, were limited in scope and did not provide a complete picture of the current state of seed potato systems in the country. The objectives of this paper are (i) to describe and analyze the status and performance of currently operating seed potato systems; and (ii) to identify and prioritize improvement options.

Major Potato Growing Areas and Types of Seed Systems

Major Potato Growing Areas

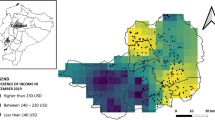

In Ethiopia, potato is grown in four major areas: the central, the eastern, the northwestern and the southern (Figs. 1 and 2). Together, they cover approximately 83% of the potato farmers (CSA 2008/2009). A brief description of each area follows:

In the central area, potato production includes the highland areas surrounding the capital, i.e. Addis Abeba, within a 100–150 km radius (Fig. 2). In this area the major potato growing zones are West Shewa and North Shewa (Fig. 1). About 10% of the potato farmers are located in this area (CSA 2008/2009). Average productivity of a potato crop ranges from 8 to 10 Mg ha−1 which is higher than the productivity in the northwestern and southern areas. This higher productivity might be due to the use of improved varieties and practices obtained from Holetta Agricultural Research Centre in the central area. In the central area potato is produced mainly in the belg (short rain season—February to May) and meher (long rain season—June to October) periods. Potato is also grown off-season under irrigation (October to January). Because of the cool climate and access to improved varieties, farmers in this area of the country also produce seed potatoes which are sold to other farmers in the vicinity or to NGOs and agricultural bureaus to be disseminated to distant farmers. In the central area, farmers grow about seven local varieties, eight improved varieties and six clones (i.e. genetic material which is not officially released).

The eastern area of potato production mainly covers the eastern highlands of Ethiopia, especially the East Harerge zone (Figs. 1 and 2). Only about 3% of the total number of potato growers is situated in this area (CSA 2008/2009), but the area is identified specifically because the majority of the potato farmers in this area produce for the market and there is also some export to Djibouti and Somalia. Potato is mainly grown under irrigation in the dry season (December to April). This season is characterized by low disease pressure and relatively high prices (Mulatu et al. 2005b). Potato is also produced in the belg (February to May) and the meher (June to October) seasons. Most farmers grow local potato varieties. However, some farmers in the vicinity of Haramaya University in the eastern area and farmers who are targeted by NGO seed programmes have access to improved varieties (Mulatu et al. 2005a). Despite the use of local varieties, the productivity of potato in this area is equivalent to the productivity in the central area. This might be due to good farm management practices triggered by the farmers’ market orientation.

Potato production areas and average yields in Ethiopia. http://research.cip.cgiar.org/confluence/display/wpa/Ethiopia. Reproduced with kind permission from the International Potato Center, Lima, Peru

The northwestern area of potato production is situated in the Amhara region (Figs. 1 and 2). It is the major potato growing area in the country, counting about 40% of the potato farmers (CSA 2008/2009). South Gonder, North Gonder, East Gojam, West Gojam and Agew Awi are the major potato production zones. Farmers mainly grow local varieties. Productivity ranges from 7 to 8 Mg ha−1. In this area, the largest volume of potato is produced in the belg season followed by irrigated potato produced off-season. Potato is also produced in the meher season. Data on genotype use in the Awi district show that there were 21 potato genotypes grown, of which 67% were local varieties. Ninety percent of the farmers grew these local varieties.

The southern area of Ethiopia in which potato is grown, is mainly located in the Southern Nations’, Nationalities’ and Peoples’ Regional State (SNNPRs) and partly in the Oromiya region. The major potato producing zones in this area are Gurage, Gamo Goffa, Hadiya, Wolyta, Kambata, Siltie and Sidama in the SNNPRS and West Arsi zone in Oromiya. More than 30% of the total number of potato farmers is located in this area (CSA 2008/2009). Potato tubers are produced under rainfed conditions and under irrigation. Productivity usually ranges from 7 to 8 Mg ha−1, whereas in some places potato productivity is even below 7 Mg ha−1. About six varieties are grown, of which four are local and two are improved (Endale et al. 2008a).

Types of Seed Potato Systems in Ethiopia

Seed systems can be defined as the ways in which farmers produce, select, save and acquire seeds (Sthapit et al. 2008). Different authors classify seed systems into different types. Struik and Wiersema (1999) and Endale et al. (2008a) classify seed systems into informal and formal, while others classify them into local and formal (World Bank et al. 2009), or farmers’ and formal (Almekinders and Louwaars 1999). The farmers’, informal or local seed systems cover methods of local seed selection, production and distribution (Louwaars 2007). The formal seed systems cover seed production and supply mechanisms operated by public or private sector specialists in different aspects of the seed system, ruled by well-defined methodologies, with controlled multiplication, and in most cases regulated by national legislation and international standardization methodologies (Louwaars 2007). In Ethiopia, we identified three seed potato systems, namely informal, alternative and formal. Each of the systems is briefly explained below.

The informal seed potato system is a seed potato system in which tubers to be used for planting are produced and distributed by farmers without any regulation. This seed system exists in all potato growing areas of Ethiopia. It is the major seed potato system. According to Gildemacher et al. (2009a), it supplies 98.7% of the seed tubers required in Ethiopia. The seed tubers supplied by this system have poor sanitary, physiological, physical and genetic qualities (Lemaga et al. 1994; Mulatu et al. 2005a; Endale et al. 2008a; Gildemacher et al. 2009a).

The alternative seed potato system is a seed potato system that supplies seed tubers produced by local farmers under financial and technical support from NGOs and breeding centres. In Ethiopia there are community-based seed supply systems which are undertaken by the community with technical and financial assistance of NGOs and breeding centres. Self-help development international (SHDI) and the FAO seed security project, both in the eastern area of Ethiopia (Getachew and Mela 2000; Mulatu et al. 2005a), can be mentioned as good examples. These NGOs formed cooperative, community-based seed enterprises (CCBSEs) which produce seed tubers of improved varieties and sell those to other farmers or back to the NGOs for further dissemination. The roles of NGOs have been to provide the financial assistance to CCBSEs and to link the CCBSEs to the breeding centre (Haramaya University in the eastern area) for technical assistance. There are also farmers’ research groups (FRG) and farmers’ field schools (FFS) in the central and northwestern areas of Ethiopia which are involved in seed potato production (Bekele et al. 2002). They are formed by the Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR). Some members of FRG and FFS in the central area of Ethiopia became specialized seed potato growers (Gildemacher et al. 2009b). These “specialized” commercial seed potato producers are local smallholder farmers. These farmers are producing better quality seed tubers than other farmers but these may still not be of standard quality. From 2002 to 2003, also some efforts were made in the southern area of Ethiopia to multiply seed potatoes by individual farmers with technical and financial assistance from breeding centres and NGOs. The alternative seed potato system supplies about 1.3% of the total supply (Gildemacher et al. 2009b).

In the formal seed potato system seed tubers are produced by licensed private sector specialists and cooperatives. There is no public formal seed potato supply system in Ethiopia. The contribution of the formal seed potato system to the overall seed tuber use in Ethiopia is very meager as both the private sector and the cooperatives are at the incipient stage. Very recently, two seed potato producer cooperatives were established and two more are under the process in the central area of Ethiopia. The Ethiopian Seed Enterprise (ESE) is not involved in seed potato production and supply because of its limited capacity. There is only one modern seed potato company in Ethiopia, i.e. the SolaGrow PLC. It is established in 2006 by a group of Dutch investors in collaboration with the Dutch potato breeding company HZPC Holland B.V. with the aim of strengthening the Ethiopian agricultural sector by producing seed potatoes. From 2006 to 2008, the PLC had already a signed agreement with HZPC Holland B.V., established central and local demonstration farms and produced 150 Mg of seed potatoes (EVD 2009).

Materials and Methods

Literature review, rapid appraisal and formal surveys, expert elicitation and field observations were carried out to analyze the current status of the seed potato systems in Ethiopia. Moreover, local knowledge was used. In the analysis the four major potato growing areas and three seed potato systems identified above were taken into account.

Framework for the Literature Review, Rapid Appraisal and Formal Surveys, and Analysis of the Performance of the Seed Systems

To describe the present status of the seed systems in Ethiopia, a literature review, a rapid appraisal survey and a formal survey were carried out and were combined with field observations and local knowledge. To analyze the performance of the present seed systems, a modified conceptual framework as suggested by Weltzien and vom Brocke (2001) was used. According to these authors a seed system can be analyzed from different perspectives and with different objectives. They suggested using the farmers’ perspective to analyze seed systems for identification of specific strengths and weaknesses. According to Weltzien and vom Brocke (2001) five functions (seed quality, appropriateness of variety, timeliness of seed availability, conditions under which the seed is available, and capacity to innovate) should be performed by a seed system to avail high-quality seed of varieties preferred by farmers in sufficient amount at the right time and for a reasonable price. These functions can be analyzed based on four process-oriented components of a seed system that overlap and interact. The four seed system components suggested by the authors are germplasm base, seed production and quality, seed availability and distribution, and information flow. For our specific analysis we slightly modified the seed system components to make the components suit our analysis. These components were (i) seed production and storage, (ii) seed tuber quality, (iii) seed availability and distribution, and (iv) information flow. We ignored the component germplasm base, for it was partly addressed in the related component seed quality. The original component seed production and quality was divided into two components, seed production and storage, and seed quality, to give due emphasis to both components. Descriptions of (i), (iii) and (iv) are largely adopted from Weltzien and vom Brocke (2001); for (ii), i.e. seed tuber quality, we used Struik and Wiersema (1999) as their description better suited seed potatoes described in this paper. Brief descriptions of these seed system components follow:

The first component, seed production and storage, refers to all activities leading to the production of seed at the time of sowing; it includes all operations of production and storage. Specific issues to address are how seed potatoes are produced, pre-treated and stored, and whether selection is practiced to identify individual plants that will be used to collect seed tubers for the next season’s crop.

The second component, i.e. seed tuber quality, can be defined as the ability of a seed tuber to produce a healthy, vigorous plant that produces a high yield of good quality within the time limits set by the growing season into which the seed is going to be used. Seed tuber quality is affected by seed health, physiological age and status, seed size, seed purity and genetic quality. The appropriateness of the variety or genetic quality of the seed is the adaptability to specific growing conditions and biotic or abiotic stresses and its food and processing quality characteristics.

The third component, seed availability and distribution, concerns the access of all farmers to appropriate seed at the appropriate time. Timeliness is crucial for obtaining the expected yield. Delays in planting usually result in yield losses and can seriously affect the development of diseases or insect populations, which in turn can affect yield and quality at harvest. Relevant questions relating to this component are: What is the actual origin of seed that farmers are planting? Is it their own production or do they get it from other sources? What role does the market play?

The fourth component, i.e. information flow, covers issues such as: What information is available about new varieties and new seed sources? Where and from whom do farmers search for new information? How is information regarding new varieties of potato and new practices exchanged among farmers? What type of information are farmers searching for? These aspects are especially relevant in the context of change and innovation.

Rapid Appraisal and Formal Survey

In 2007, a survey was undertaken in three major potato growing districts of Ethiopia, namely Juldu and Degem districts in the central part and Banja district in the northwestern part of Ethiopia, to gather data on the status of the use of improved potato technologies, including new varieties and improved cultural practices. Jeldu district is located in the West Shewa zone of the Oromia region at 128 km from Addis Abeba going southwest; Degem district is located in the North Shewa zone at 125 km from Addis Abeba going northwest; Banja district is located in the Agew Awi zone of the Amhara region at 434 km from Addis Abeba going northwest (Fig. 1). Data collection was undertaken in three successive stages. First, secondary data was collected from relevant published and unpublished sources. Second, based on the information obtained from secondary data a checklist was prepared to conduct a rapid appraisal survey that helped to collect qualitative information and gain insight in the use of potato technologies by potato producers. Third, a formal survey was conducted using a structured questionnaire to collect quantitative data on the use of improved varieties and practices. This formal survey was conducted among two categories of farmers. One category consisted of farmers who hosted demonstration, verification and scaling-up trials on the use of cultural practices of improved potato varieties, undertaken by agricultural research institutions. The second category comprised potato producing farmers who did not directly host any kind of potato demonstration, verification or scaling-up trials. A total of 127 farmers in the first category (61 from Jeldu, 50 from Degem and 16 from Banja districts) and 209 farmers in the second category (76 from Jeldu, 54 from Degem and 79 from Banja districts) were selected randomly. Descriptive statistics, mean and percentage, were employed to analyze the data.

Expert Elicitation

A workshop was organized to elicit national and international seed potato experts’ opinions on seed potato system improvements in Ethiopia. The half-day workshop took place in Spring 2009. In total 13 experts attended, five of them were Wageningen University professors, four were Netherlands-based research and development project managers working in developing countries, two were International Potato Center (CIP) researchers and another two were Ethiopian PhD students doing research on potato. The meeting was set up in three blocks. During the first block we presented the main findings from literature and posed the question whether important elements were missing. In the second block, experts evaluated the informal, alternative and formal systems. Evaluations were differentiated according to regions (for the informal system we distinguished between the central, eastern, northwestern and southern regions; for the alternative system between the central, eastern and northwestern regions) or organizational form (for the formal system these were cooperatives versus Private Limited Company (PLCs). For each system, region or organizational form the same three assignments were to be carried out, i.e. (i) prioritize general improvement options in the seed system by dividing 100 points; (ii) prioritize items of improving seed quality by dividing 100 points; and (iii) indicate top-3 steps for the roadmap towards improvement. Assignments (i) and (ii) were closed-type questions as we already indicated the improvement items, while assignment (iii) was an open question. General improvement items included production methods, storage methods, seed quality, seed availability and distribution, information flow, spread of new varieties, and cost-benefit ratio, from which the latter two were added by experts during the first block of the workshop. Quality improvement items were purity, genetic quality, seed health, seed size, physical damage, and physiological age. For the roadmap, experts were free to list the steps to be taken to improve each of the four seed potato systems (informal, alternative, formal cooperative and formal private). In the third block of the workshop we discussed the feasibility of “one overall seed potato system for Ethiopia”.

Current Status of Seed Potato Systems

The main characteristics describing the current status and performance of seed potato systems in Ethiopia are summarized in Table 1.

Seed Potato Production and Storage

Seed Potato Production Methods

Generally, in all areas of Ethiopia, there is no separate plot and management for ware and seed potato production. Mostly, potato tubers are sorted into ware and seed immediately after harvest. For most potato producers seed potato is usually considered as the by-product of ware potato. Only some farmers in the central and northwestern areas of Ethiopia have recognized the problems of using part of ware potato as planting material, such as disease transmittance and resulting yield loss. In the central and northwestern areas, some farmers practice positive selectionFootnote 2 and some also grow seed potatoes on a separate piece of good quality land. In our survey in 2007, 13% of the farmers in the district Degem and 15% of the farmers in the district Jeldu in the central area and 8% of the farmers in the district Banja in the northwestern area produced seed potatoes by positive selection, whereas 1% of the farmers in district Degem, 14% of the farmers in the district Jeldu and 6% of the farmers in the district Banja produced seed potato on separate plots (Table 1). In another study in the central and northwestern areas of Ethiopia, 9% of farmers were found to produce seed potatoes through positive selection and 2% of the farmers were found to produce seed potatoes on separate plots (Gildemacher et al. 2009b). In the southern area there is no practice of positive selection or use of separate plots for the production of seed tubers. According to Mulatu et al. (2005a) farmers in the eastern area of Ethiopia usually do not produce seed tubers on separate plots. In this area of the country, there is no positive selection either.

Seed Potato Storage Methods

Seed potato storage is a common practice in all potato producing areas of Ethiopia. Farmers store seed potato by leaving the tubers in the soil un-harvested (postponed harvesting); by other traditional storage methods like in a local granary, on bed-like structures or the floor in their house; or by diffused-light storage (DLS). Because of storage and other post harvest problems Ethiopia loses 30–50% of its potato production (Endale et al. 2008b). Types of storage are described in more detail below.

-

i.

Postponed harvesting as storage mechanism

Postponed harvesting is the most commonly used storage method for ware potatoes in the highland and northwestern areas of the country to extend piece-meal consumption and also to wait for a better price (Endale et al. 2008b). According to these authors, tubers can be kept up to 4 months without major quality loss in cool highlands. This storage method is also used to store seed potatoes. Our survey revealed that about 37% of the farmers in Banja in the northwestern area of Ethiopia left the potato tubers for seed un-harvested in the field, whereas only 1% (Jeldu) to 3% (Degem) of the farmers in the central area used this method (Table 1). In a study undertaken in the central and northwestern areas of Ethiopia, Gildemacher et al. (2009b) found that 47% of the potato farmers leave seed potatoes in the soil un-harvested. This storage method was not reported in seed potato studies in the eastern area of Ethiopia. There is also no information on the presence of this storage type in the southern area of Ethiopia. Postponed harvesting as storage mechanism has been creating problems in potato production for it could allow more accumulation of tuber-borne diseases than early harvesting (Endale et al. 2008a). In-ground storage of potato is also associated with large losses: in the Gojam and Gonder areas of the northwest losses of up to 50% have been reported caused by tuber moth and ants (Tesfaye et al. 2008).

-

ii.

Other traditional storage methods

Farmers also store seed potatoes in bags stacked on the floor in untidy places in the house where there is no ventilation, heaped loosely or put on a bed-like structure. Forty seven per cent of the farmers in the district Degem and 46% of the farmers in district Jeldu in the central area of Ethiopia (this study; Table 1) and 73.6% in the eastern area of Ethiopia (Mulatu et al. 2005a) used bags to store their seed potatoes. About 45% of the potato farmers of Jeldu district in the central area of Ethiopia and 21% of the farmers of Banja district in the northwestern area of Ethiopia heap their seed potatoes loosely while 33% of the farmers of Banja district in the northwestern area of the country use a bed-like structure (Table 1). Mulatu et al. (2005a) also found that about 26.4% of the farmers in the eastern area of Ethiopia piled up their seed potatoes in an open place or in a corner of their house. However, there are also farmers who store their potatoes in a better place. In a study made in the central and northwestern areas of Ethiopia, about 18% of the farmers were found to use light spaces in the house to store their seed potatoes (Gildemacher et al. 2009b). In the southern area farmers store seed potatoes in their home or in a store constructed for this purpose. Seed and ware potatoes are stored side by side in the same store or home. In the Shashemene district of the southern area, farmers cover stored ware and seed tubers with teff straw to protect the tubers from sun light. They use a thicker cover for the seed than for the ware. The farmers increase the thickness of the seed tuber cover a few weeks before planting. The farmers believe that an increase in the thickness of the cover will help the seed tubers to break dormancy and thereby encourage sprouting.

-

iii.

Diffused light storage

Diffused light storage (DLS) is a storage method using a low cost rustic structure to store seed tubers. It maintains seed tuber quality by allowing diffusion of light and free ventilation which suppress sprout elongation and thereby slow-down aging of the sprout. In an experiment carried out in Holetta to quantify the effects of storage methods, Lemaga et al. (1994) found that seed tubers stored in multi-layered burlap sacks (similar to farmers’ dark storage method) produced significantly taller sprouts and lost significantly more weight than those stored in DLS. This shows that DLS has a better potential to keep quality seed tubers than the traditional storage method. Even though the storage performance differs from variety to variety, seed potatoes can be stored in DLS up to 7 months without considerable depreciation of seed quality (Endale et al., 2008b). The DLS is usually used for the storage of seed potatoes of improved varieties whereas the other storage mechanisms are used for the storage of seed potatoes of local varieties. The reason for this might be that farmers are not aware of the importance of DLS for the storage of local varieties.Footnote 3

In the central and northwestern areas of Ethiopia only 5% of potato farmers were found to use DLS (Gildemacher et al. 2009b) but the use of DLS for seed tubers of improved varieties is becoming common in the central area of Ethiopia. About 87% of the farmers in the central area and 25% in the northwestern area were found to use DLS for storage of seed potatoes of improved varieties (Tesfaye et al. 2008). The use of DLS is slowly increasing in the northwest. In the eastern area of Ethiopia, the use of DLS is restricted to the cooperative community based seed enterprises established by the FAO seed security project (Mulatu et al. 2005a). For the southern area of the country there is no literature on the storage methods. The reason for not using DLS, for about 22% of the farmers in the central area of Ethiopia and about 71% of the farmers in the northwestern area of Ethiopia was lack of awareness. Seed tubers stored in DLS systems may become infected or infested with tuber moths, aphids, late blight or bacterial wilt; the use of insect screens can keep insects out, but not the pathogens.

Seed Quality

In this section we discuss the following aspects of potato seed quality: purity, genetic quality, health, size, physical damage and physiological age. In Ethiopia, quality of seed tubers is a serious problem because of varietal mix-up, poor storage mechanisms, prevalence of diseases and pests and poor knowledge of seed selection.

-

i.

Seed potato purity

In all potato growing areas of Ethiopia most farmers use seed potatoes of unknown origin. Farmers obtain their seed tubers usually from the local market if they do not set aside tubers from their own previous season production. Different varieties of potato are mixed during harvest or trade. Mulatu et al. (2005a) studied tuber characteristics of the improved potato variety Al-624 released in 1987. The study revealed that only 46–52% of the tubers found in farmers’ plots resembled tubers of this variety retained by the breeding institution (Haramaya University). On potato field inspections made in several villages of the districts Alemaya and Kersa in the eastern area an average of 4–5 varieties was found to be grown as a mixture per plot (Mulatu et al. 2005a). It was observed on seed potato markets in the central and northwestern areas that traders mixed seed tubers purchased from different growers (Guenthner 2006). In the southern area, the same practice was observed. For instance, in the district Shashemene, phenotypically different potato plants were observed in the same field which might have occurred due to genetic differences or differences in physiological age of the seed tubers. Planting of mixed seed tubers results in a produce with a within-lot variation in cooking and processing qualities. There are also problems in timing of the harvest because of differences in maturity between plants.

-

ii.

Seed potato genetic quality

Potato variety improvement research has been undertaken in Ethiopia since 1975 with the objective of developing high-yielding, late-blight resistant and widely adaptable varieties. In the last two decades (from 1987 to 2006) about 18 improved varieties, which are adaptable to altitudes ranging from 1000 to 3200 m and receiving 750–1500 mm rainfall with on farm yielding ability ranging from 19 to 38 Mg ha−1, were released (Gebremedhin et al. 2008).

Genetic quality also includes food and processing quality. According to Endale et al. (2008b), improved potato varieties, namely Digemegn, Zengena, Jalele, Gorebella, Guassa, Menagesha, Tolcha and Wechecha, had an acceptable dry matter concentration and specific gravity for processing. No processing is currently done in the northwestern area.

-

iii.

Seed potato health

Late blight [Phytophthora infestans (Mont.) de Bary] is common in all potato growing areas of Ethiopia. In many parts of the country it is the cause for the shift of potato production from the long rainy season (meher) to off-season production, despite the high potential yield in the long rainy season (Bekele and Eshetu 2008). According to Bekele and Eshetu (2008), local varieties do not cope with the disease pressure in the main rainy season and often are wiped out, particularly in the highlands. When seed tubers become infected by Phytophthora infestans they may rot during storage or will fail to produce emerging and surviving plants.

Viruses [e.g., Potato leaf roll virus (PLRV) and Potato virus Y (PVY)] and bacterial wilt (Ralstonia solanacearum) are causing potato plant and tuber degeneration in Ethiopia. The prevalence of these diseases is high in the low to medium altitudes (Bekele and Eshetu 2008). On a seed degeneration experiment undertaken in Holetta Agricultural Research Centre from 1997 to 2000, percent yield reductions due to viruses (mainly PLRV and PVY) were recorded of 62, 45, 44 and 41 in the varieties Tolcha, Genet, AL-624 and Awash, respectively (Bekele and Eshetu 2008). Because these pathogens attack the foliage, root system and tubers, they are important throughout the crop cycle. Potato tuber moth, PTM (Phthorimaea operculella) is affecting seed potatoes in the field and stored in DLS (Bayeh et al. 2008).

Farmers can produce relatively healthy seed potatoes by planting on appropriate planting dates, by applying positive selection, by allotting separate, better-quality, isolated plots to seed production and by timely haulm destruction. There are efforts underway to produce healthy seed potatoes by farmers in some parts of Ethiopia even though they are limited. In the central area of Ethiopia farmers commonly destroy the haulm of the part of their potato field reserved for seed. Thirty nine to fifty four per cent of the farmers in the central area of Ethiopia had adopted the recommended haulm destruction date. According to Endale et al. (2008a) and Gebremedhin et al. (2008), disease and insect pressures in the highlands, especially late-blight pressure, was considerably reduced because of the use of disease-resistant varieties. Farmers also renew their seed stock. According to Gildemacher et al. (2009a, b), 44% of farmers in the central and northwestern areas of Ethiopia renew seed on average every three seasons, but only 15% of their seed stock each time. The improvement in the practices to produce better quality seed potato in the central area of Ethiopia is achieved because of the concerted efforts of the Ethiopia Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR). Holetta Agricultural Research Centre of the EIAR has been assisting farmers in the central area of Ethiopia in providing seed and training through its farmers’ research group (FRG) and farmers’ field school (FFS).

Because of the use of home saved seed, use of seed potatoes of unknown origin from local markets, limited use of resistant varieties, poor storage practices like leaving potato underground un-harvested and only limited adoption of haulm killing and selection practices by farmers, the seed tubers used by most potato producers cannot be healthy. However, according to Endale et al. (2008a) and Gebremedhin et al. (2008), in the highland areas, disease and insect pressures, especially late-blight pressure, were considerably reduced because of the use of disease-resistant varieties.

-

iv.

Seed potato size

Among the Ethiopian smallholder farmers in all areas, it is common practice to save tubers for seed that are too small and inferior to be sold for consumption (Mulatu et al. 2005a; Endale et al. 2008a; Gildemacher et al. 2007). Small-sized tubers may have two problems. The first one is delayed emergence and low sprout vigour and number because of low food reserve (Lommen 1994; Lommen and Struik 1994). The second is that they might be a progeny of an infected mother plant and thus infected by diseases, because infected mother plants usually give small tubers (Struik and Wiersema 1999). In Ethiopia, the use of small potato tubers as seed might have contributed to the building up of high level of disease especially in the locally grown varieties.

However, there are areas where many farmers use medium-sized tubers for seed. For instance, 72% of farmers in district Degem, 66% of farmers in district Jeldu in central area and 63% of the farmers in district Banja in northwestern area selected medium-sized tubers from the whole produce immediately after harvest, to save for seed (Table 1). Also Gildemacher et al. (2009b) found that 40% of the potato farmers in the northwestern area of Ethiopia selected medium-sized tubers for seed.

-

v.

Seed potato physical damage

Physical damage includes cuts, bruises and holes, inflicted on tubers during harvesting, storage, packaging and transportation. In a study undertaken on seed potato tubers stored on-farm by using a traditional storage method, in two districts of the eastern area, Kersa and Alemay, 8% of the tubers were found to be damaged during harvest (Mulatu et al. 2005a). There is no information on physical damage of seed potatoes for the remaining three major potato growing areas.

In Ethiopia potato tubers are harvested, stored, packaged and transported with little care to prevent physical damage to the tuber, most likely because of the low level of knowledge about the consequence of physical damage by all parties involved. The tools used by farmers to dig out tubers from the soil might not be appropriate (too sharp or elongated ending). Physical damage in seed tubers may also occur during storage because of piling of one sack upon the other and lack of ventilation. Potatoes are usually packed in sacks which cannot protect tubers from any external pressure causing bruising and stabbing. Potato sacks are usually transported by pack animals and are tied by ropes on their back, which may cause bruising to tubers. Distant transportation takes place by lorries. In this case loading and unloading is done by throwing up and down the tuber sacks. The tubers may be loaded with other sharp or beneath heavy materials which might cause damage to the tubers.

-

vi.

Seed potato physiological age

Effects of physiological ageFootnote 4 on yield are of paramount importance for a country like Ethiopia where there is more than one potato production cycle per year, very poor seed tuber handling and poor storage conditions (Struik and Wiersema 1999; Endale et al. 2008b). Multiple-season production has two physiology related problems, a short time gap (limited time for a seed tuber to break dormancy) between adjacent seasons and a long time gap (resulting in physiologically old seed with reduced vigor) between un-adjacent seasons. According to Endale et al. (2008a) farmers in the district Shashemene, West Arsi zone, in the southern area, abandoned production of the improved variety Genet despite its good yielding ability compared to other varieties, because of the short dormancy period (less than 52 days) whereas the period between the off-season (January to March) and the meher season (June to September) is about 2 months and the period between two successive seasons of the same type is 8 months.

In the southern area, farmers use seed tubers saved on farm and/or imported from other, distant places. We observed that the same farmer planted seed tubers from different origins on different plots in the same growing season. There is a difference in the physiological age of the seed tubers saved on farm and those imported. Field observations in Shashemene district in October 2009 indicated that the seed tubers imported from a low temperature area were large in size, sprouted well and gave more stems per seed tuber planted than the local farm-saved seed tubers, which had been stored in this high temperature area. Farmers do not practice de-sprouting before planting. However de-sprouting might increase the number of stems per seed tuber planted. In the current plant stands, the low number of stems per plant contributes to a suboptimal development of the foliage, resulting in incomplete capture of the available incoming radiation. Therefore, increasing the number of stems per seed tuber planted by a de-sprouting treatment might be beneficial for final tuber yield.

Seed potatoes produced in high-altitude areas often have a good physiological condition. However, such seed tubers may contain latent bacterial wilt or late blight.

Seed Availability and Distribution

There are several sources of seed potato in Ethiopia: own savings, local open markets, village markets, breeding centres, NGOs, vegetable traders, district agricultural bureaus, specialized seed potato growers, relatives and friends. Seed tubers from most of these sources were originally not specifically designated for seed, but were simply produced as potato tubers that can be used as ware and seed. However, there are efforts underway to produce seed tubers by specialized seed growers and a private limited company. There are also about 18 improved potato varieties grown in Ethiopia. However, according to Gebremedhin et al. (2008) and Mulatu et al. (2005a), not all the 18 varieties have been widely distributed and grown by farmers due to the very limited capacity of the alternative seed supply system in the country.

Nevertheless there is difference in the proportion of tubers of improved and local varieties that are used as seed. For instance, our survey indicated that in the central and northwestern areas of Ethiopia, out of the total amount of tubers of improved varieties produced, 46% was used as seed, 49% was used for consumption and 5% was used as gift (Table 1). Without distinguishing between improved and local varieties, 24% and 75% of the total produce of tubers were used as seed and ware, respectively (Gildemacher et al. 2009b).

Seed tubers produced in the central area are sold to farmers in the vicinity as well as to those hundreds of kilometers away. The distribution to distant areas is usually undertaken by traders, agricultural bureaus or NGOs. The main destinations of the seed tubers produced in the central area are the central area itself and the western and southwestern areas. For instance seed tubers produced in the district Jeldu were used by many farmers within the district, neighbouring districts and far distant areas like Nekemte (E. Wellega), Dembidolo (W. Wellega), Metu (Illubabor), and Gimbi (W. Wellega) (Endale et al. 2008a). The seed tubers produced in the cool central areas are most likely at a suitable physiological age and thus give better yield than seed tubers available in the other, warmer areas.

In the eastern area of Ethiopia, own savings and local markets are the two major sources (Mulatu et al. 2005a; Emana and Hadera 2007). Seed potato transactions are usually undertaken by cash because of the bulkiness of tubers and the high amount of seed needed for a field prevents farmer-to-farmer seed exchange and gifts like in other crops (Mulatu et al. 2005a).

In the southern area of Ethiopia, seed tubers flow from place to place depending on season. Seed tubers can be transported from and to highland, mid altitude and irrigated areas. Some authors claim that there is a large volume of seed tubers flowing from irrigated areas to places where potato is produced under rain-fed conditions. For instance, Endale et al. (2008a) revealed that most of the farmers in the Shashemene area use seed tubers produced under irrigation in Wondogenet and Shemena areas. Seed potatoes produced in the southern area are also distributed to the western and southwestern areas of Ethiopia even though it might not be significant. In the Shashemene market seed tubers are sold mainly by men while ware is mainly sold by women. Seed tubers availed to Shashemene market were offered to be sold as seed and ware. The seed potato flows in northwestern and eastern Ethiopia are not documented.

Information Flow

Farmers can obtain information on name, source, yielding ability, marketability and food quality of varieties and production practices from various sources, such as family members, neighbouring farmers, extension agents, NGO employees, researchers, and potato traders. Gildemacher et al. (2009a) found that about 58.7% of the farmers in North Shewa and West Shewa zones of the central area and East Hararghe zone of the eastern area of Ethiopia obtain information on the aforementioned characteristics of varieties from farmers in their own community. Tesfaye et al. (2008) found that the majority of the farmers (62%) in the central area of Ethiopia obtained information on improved potato technologies from Holetta Research Centre, whereas 33% obtained it from fellow farmers and only 4% from the office of agriculture. Own community and research centres like Holetta Agricultural Research Centre are the major sources of information for seed potato technologies.

In Ethiopia, seed tubers are sold either packed in sacks without any label or loose in open markets. There is no way by which information about variety and quality is transferred from seller to buyer except trust. There is need for a system that differentiates high quality seed tubers from low quality tubers, given the importance of high-quality seed tubers, the mixing of different varieties and the sanitary condition of the tubers. Guenthner (2006) suggested a three colors tag system to show high, medium and low quality seed tubers. Colors were used as identification for illiterate farmers and criteria for different qualities were suggested.

Expert Elicitation on Improvement Options

Improvement of Seed Potato Systems

The mean weights given by experts to different seed system components regarding their importance in order to improve each of the existing potato seed systems in Ethiopia are given in Table 2. For all existing seed potato systems (informal, alternative, formal cooperative and formal PLC) experts deemed improvement of seed quality to be important. The importance in the improvement of seed availability and distribution was perceived to be higher in the alternative, formal cooperative and formal PLC seed systems than in the informal seed system. In the informal seed system the improvement of production and storage method was believed to be more important than in the remaining three seed systems.

Improvement in Seed Tuber Quality

The mean scores of experts’ opinion on the importance of improvement of seed quality are given in Table 3. Experts believed that improvement in seed health, physiological age and genetic quality were more important than the improvement in purity, size and physical damage of seed tubers for all seed systems. The importance of improvement of seed health was perceived to be of top priority in all seed systems. With regard to the need for improvement in physiological age, experts gave relatively more weight in the less advanced seed systems (informal, formal cooperative and alternative) compared to the advanced formal seed system (formal PLC). Experts gave higher scores for the importance of improvement in seed genetic quality for alternative, formal-cooperative and formal-PLC seed systems than for the informal seed system. The reason might be that the alternative and formal seed systems are expected to multiply and disseminate seed tubers of new varieties.

Roadmap Towards Improvement

The opinion of seed experts on the steps to be taken to improve the seed systems in Ethiopia is given in Table 4. For improving the informal seed system, the top 3 steps mentioned were improving the awareness and skill of farmers, improving quality of the seed tubers used by the farmers, and improving farmers’ market access.

To improve the alternative seed potato system, experts suggested availing starter seed tubers of new varieties to farmers in the alternative seed system as the most important first step to be taken. Improving seed quality, designing sustainable seed quality control methods and reducing cost of seed production were listed with equal importance after availing of starter seed tubers of new varieties. Experts suggested the development of a seed quality control system that can be managed by the farmers themselves. There was also a suggestion on putting a realistic disease tolerance limit beyond which seed tubers can no longer be used as seed. In order to implement this suggestion, a uniform method for disease assessment needs to be established.

Experts suggested designing sustainable seed quality control methods and providing new varieties as starter seed to cooperative members as the top-2 steps to be taken to improve the formal cooperative seed potato system. Improving awareness and skill of the cooperative members on seed production technologies, improving market access, expanding seed tuber production, and reducing costs were mentioned as the third step to be taken to improve the formal cooperative seed potato system. The experts suggested the seed quality control method should be designed in a way it can be implemented by cooperative members. For improvement of the PLC-based seed system, providing seed of new varieties, and improving awareness and skills of farmers were mentioned as the main two measures to be taken; improving market access, designing control methods and reducing cost were mentioned as the third important steps. Some of the experts suggested the use of pro-poor varieties by PLC, i.e. varieties with the potential to become adopted by poor subsistence farmers. The PLC may create awareness by setting demonstration sites for the farmers.

Is it Possible to have One Overall Seed System?

Experts perceived it to be unlikely to have one seed potato system in Ethiopia that satisfies the interests of all potato producers. They generally agreed that improvements are needed in all systems. This is in line with ideas from Maredia and Howard (1998) who stated that a well-functioning seed system is one that uses the appropriate combination of informal, formal, market and non-market channels to efficiently meet the demand for quality seeds. The experts suggested looking for ways in which the existing seed systems can support each other and supply quality seed tubers. The experts also emphasized the need for transforming alternative seed systems from the prevailing situation of unbranded seed production, to a self-regulating and self-certifying seed production.

Conclusions

In this study we describe the state of affairs of seed potato systems in Ethiopia and we attempt to elicit the main areas of improvement and the main steps to be taken in the roadmap towards these improvements. With regard to the current status of seed potato systems we conclude that in general all three seed potato systems operating in Ethiopia, i.e. the informal, alternative and formal system, have problems in undertaking their functions as a seed system. More specifically we conclude:

-

Seed tubers supplied by the informal seed potato system (supplies 98.7% of seed tubers used in the country) are deemed to be poor in health, unsuitable in physiological age, poor in genetic quality, impure (varietal mix-up), physically damaged and inappropriate in size. Besides, in the informal seed potato system, seed tubers are produced usually as part of ware and stored under poor conditions. In this seed system farmers usually use varieties of unknown origin and improved varieties are not available to the majority of the farmers. Lack of awareness about the availability and use of improved technology and practices has also impeded adoption of potato technologies.

-

The alternative potato system, which co-exists with the informal seed system in the central and eastern areas, supplies better quality seed tubers than the informal seed potato system. However, the amount of seed tubers supplied by the alternative seed potato system is very small (1.3%) and thus the system still has limited impact on improvement of potato production in Ethiopia.

-

The formal seed system co-exists with the informal and alternative seed potato systems but only in the central area. It is at the incipient stage and its contribution to the overall seed system is negligible.

The most important problems of the seed systems in Ethiopia seem to be the insufficient seed tuber quality and the unavailability of seed tubers of improved varieties. This is supported by experts’ suggestions for improvements in the existing seed systems.

-

To improve the informal seed potato system experts listed increasing awareness and skills of farmers, improving seed tuber quality, and improving market access as top-3 steps.

-

To improve alternative and formal seed systems experts listed availing new varieties, designing quality control methods and reducing cost of seed production as top-3 steps.

-

To improve the overall seed potato supply in the country, experts postulated the co-existence and a good linkage of the three seed systems, and development of self-regulatory and self-certification in the informal, alternative and formal cooperative seed potato systems.

As a continuation of this study several studies are underway. These include analysis of options to improve the seed tuber quality and designing of an improved seed potato supply chain.

Notes

Potato production system comprises all processes and activities (land preparation through harvesting) undertaken to produce ware or seed potatoes.

Positive selection means selecting only the healthy-looking mother plants, showing good production characteristics, for seed collection (Gildemacher et al. 2007)

Potato tubers stored in DLS or any light space, cannot be used for consumption. Storage in light results in high levels of glycoalkaloids, which are harmful after intake (Struik and Wiersema 1999). However, 3% of the farmers in district Jeldu in the central area and 2% of farmers in district Banja in the northwestern area were found to store ware potatoes in DLS. Glycoalkaloids protect tubers to some extent against certain pests and diseases (Tarn et al. 2006).

Physiological age is the stage of development of a tuber, which is modified progressively by increasing chronological age, depending on growth history and storage conditions (Struik and Wiersema 1999). Chronological age is tuber age from the time of tuber initiation, expressed in days, weeks or months.

References

Almekinders, C.J.M., and N.P. Louwaars. 1999. Farmers’ seed production: New approaches and practices, 291. London: Intermediate Technology Publications.

Bayeh, M., A. Refera, B. Wubshet, and B. Asayehegn. 2008. Potato pest management. In Root and tuber crops: The untapped resources, ed. W. Gebremedhin, G. Endale, and B. Lemaga, 97–112. Addis Abeba: Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research.

Bekele, K., and B. Eshetu. 2008. Potato disease management. In Root and tuber crops: The untapped resources, ed. W. Gebremedhin, G. Endale, and B. Lemaga, 79–96. Addis Abeba: Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research.

Bekele, K., G. Woldegiogis, F. Kelemework, A. Mela, O.M. Olanya, P.T. Ewell, and R. El-Bedewy. 2002. Integrated potato late blight management: Experience of farmer field school in Dendi district. In Towards farmers’ participatory research: Attempt and achievements in the central highlands of Ethiopia. Proceedings of client oriented evaluation workshop, 16–18 October 2001, Holetta, Ethiopia, ed. G. Kenei, Y. Gojjam, K. Bedane, C. Yirga, and A. Dibabe, 56–67. Holetta: Holetta Agricultural Research Centre.

CSA (Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia). 2008/2009. Agricultural sample survey: Report on area and production of crops, Addis Abeba, Ethiopia, p 126.

Emana, B., and G. Hadera. 2007. Constraints and opportunities of horticulture production and marketing in Eastern Ethiopia. Dry land coordination group (DCG) report no. 46. Ås, Norway.

Endale, G., W. Gebremedhin, and B. Lemaga. 2008a. Potato seed management. In Root and tuber crops: The untapped resources, ed. W. Gebremedhin, G. Endale, and B. Lemaga, 53–78. Addis Abeba: Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research.

Endale, G., W. Gebremedhin, K. Bekele, and B. Lemaga. 2008b. Post harvest management. In Root and tuber crops: The untapped resources, ed. W. Gebremedhin, G. Endale, and B. Lemaga, 113–130. Addis Abeba: Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research.

EVD (Agency of Ministry of Economic Affairs). 2009. Introduction of a seed potato production system in Ethiopia. Project number 174384. Information available at www.evd.nl. Date of accession: 13/9/2009.

FAO. 2008. Potato World: Africa—International Year of the Potato 2008. http://www.potato2008.org/en/world/africa.html. Date of accession: 1/1/2009.

Gebremedhin, W., G. Endale, and B. Lemaga. 2008. Potato variety development. In Root and tuber crops: The untapped resources, ed. W. Gebremedhin, G. Endale, and B. Lemaga, 15–32. Addis Abeba: Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research.

Getachew, T., and A. Mela. 2000. The role of SHDI in potato seed production in Ethiopia: Experience from Alemaya integrated rural development project. African Potato Association Conference Proceedings 5: 109–112.

Gildemacher, P., P. Demo, P. Kinyae, M. Nyongesa, and P. Mundia. 2007. Selecting the best plants to improve seed potato. LEISA Magazine 23(2): 10–11.

Gildemacher, P., W. Kaguongo, O. Ortiz, A. Tesfaye, W. Gebremedhin, W.W. Wagoire, R. Kakuhenzire, P. Kinyae, M. Nyongesa, P.C. Struik, and C. Leewis. 2009a. Improving potato production in Kenya, Uganda and Ethiopia. Potato Research 52: 173–205.

Gildemacher, P., P. Demo, I. Barker, W. Kaguongo, W. Gebremedhin, W.W. Wagoire, M. Wakahiu, C. Leeuwis, and P.C. Struik. 2009b. A description of seed potato systems in Kenya, Uganda and Ethiopia. American Journal of Potato Research 86: 373–382.

Guenthner, J.F. 2006. Development of on-farm potato seed tuber production and marketing scheme. Agricultural economics extension series no. 06-01, July 2006. University of Idaho, Moscow.

Lemaga, B., G. Hailemariam, and W. Gebremedhin. 1994. Prospects of seed potato production in Ethiopia. In Proceedings of the second national horticultural workshop of Ethiopia, ed. E. Hareth and D. Lemma, 254–275. Addis Abeba: Institute of Agricultural Research and FAO.

Lommen, W.J.M. 1994. Effect of weight of potato minitubers on sprout growth, emergence and plant characteristics at emergence. Potato Research 27: 315–322.

Lommen, W.J.M., and P.C. Struik. 1994. Field performance of potato minitubers with different fresh weights and conventional tubers: Crop establishment and yield formation. Potato Research 37: 301–313.

Louwaars, N. 2007. Seeds of confusion: The impact of policies on seed systems. PhD dissertation, Centre for Genetic Resources, WUR, The Netherlands.

Maredia, M., and J. Howard. 1998. Facilitating seed sector transformation in Africa: key findings from the literature. Policy synthesis for USAID—Bureau for Africa, FS II Policy synthesis No. 33.

Mulatu, E., E.I. Osman, and B. Etenesh. 2005a. Improving potato seed tuber quality and producers’ livelihoods in Hararghe, Eastern Ethiopia. Journal of New Seeds 7(3): 31–56.

Mulatu, E., E.I. Osman, and B. Etensh. 2005b. Policy challenges to improve vegetable production and seed supply in Hararghe, Eastern Ethiopia. Journal of Vegetable Science 11(2): 81–106.

Sthapit, B., R. Ram, C. Pashupati, B. Bimal, and S. Pratap. 2008. Informal seed systems and on-farm conservation of local varieties. In Farmers, seeds and varieties: supporting informal seed supply in Ethiopia, ed. M.H. Thijssen, Z. Bishaw, A. Beshir, and W.S. de Boef, 133–137. Wageningen: Wageningen International.

Struik, P.C., and S.G. Wiersema. 1999. Seed potato technology, 383. Wageningen: Wageningen Pers.

Tarn, T.R., G.C.C. Tai, and Q. Liu. 2006. Chapter 5: Quality improvement. In Handbook of potato production, improvement, and postharvest management, ed. J. Gopal and S.M. Paul Khurama, 147–178. Binghamton: Food Products.

Tesfaye, A.B., K. Bedane, C. Yirga, and W. Gebremedhin. 2008. Socioeconomics and technology transfer. In Root and tuber crops: The untapped resources, ed. W. Gebremedhin, G. Endale, and B. Lemaga, 131–152. Addis Abeba: Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research.

Weltzien, E., and K. vom Brocke. 2001. Seed systems and their potential for innovation: Conceptual framework for analysis. In Targeted seed aid and seed system interventions: Strengthening small farmer seed systems in East and Central Africa. Proceedings of a workshop held in Kampala, Uganda, 21–24 June 2000, ed. L. Sperling, 9–13. Kampala.

World Bank, FAO, and IFAD. 2009. Gender in seed production and distribution. Gender in Agriculture Sourcebook, 764. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank field survey participants for sharing useful insights into current seed potato circumstances. Workshop participants are acknowledged for their willingness to participate in the elicitation workshop and for providing their valuable opinions on how to improve seed potato systems in Ethiopia. The Wageningen University International Research and Education Fund is acknowledged for funding this research as well as the PhD training.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Hirpa, A., Meuwissen, M.P.M., Tesfaye, A. et al. Analysis of Seed Potato Systems in Ethiopia. Am. J. Pot Res 87, 537–552 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12230-010-9164-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12230-010-9164-1